inequality

What is the point of power if it is not to help the most vulnerable and least well off, which there is no sign that Labour will do?

As the Observer noted yesterday:

Schools are finding beds, providing showers for pupils and washing uniforms as child poverty spirals out of control, headteachers from across England have told the Observer.

School leaders said that as well as hunger they were now trying to mitigate exhaustion, with increasing numbers of children living in homes without enough beds or unable to sleep because they were cold. They warned that “desperate” poverty was driving problems with behaviour, persistent absence and mental health.

They added a headteacher reporting that

The school had many children living in “desperate neglect”. “Kids are sleeping on sofas, in homes with smashed windows, no curtains, or mice,” he said. “I come out of some of these properties and get really upset.”

The details come from:

report published on Friday by the Child of the North campaign, led by eight leading northern universities, and the Centre for Young Lives thinktank, warned that after decades of cuts to public services, schools were now the “frontline of the battle against child poverty”, and at risk of being “overwhelmed”. It called on the government to increase funding to help schools support the more than 4 million children now living in poverty in the UK.

There is no point now thinking that we have a Conservative government. They are in such disarray that they no longer function.

Instead we have to ask what Labour might do about this, and the answer we are told, time and again, is that they will say there is no money left.

That is because they will not tax capital gains fairly, as if they are income, which is exactly what they are.

And it is because they still want to massively subsidise the savings of the wealthy by providing excessive tax relief on the pension contributions of the wealthiest in our society.

It is also because they refuse to tax income from wealth at the rates paid by those with income from work.

And it is because they still think that those on high earnings should pay much less, proportionately, in national insurance than those on low earnings should.

Just put those right and you have round £50 billion (or more) to tackle this issue.

If Labour will not do that let’s be quite clear about what it will be doing: it will be choosing to perpetuate poverty. So far, that seems to be its plan.

Nothing will ever make Labour acceptable to me until they say they they are going to really tackle the issues arising from poverty, and to root out its causes. Why should I tolerate them when they could do that, and so far say that they will not?

What is the point of power if it is not to help the most vulnerable and least well off?

Levelling Up: 90% of Promised Schemes are Nowhere Near Completion

Ninety per cent of the "Levelling Up" projects promised by Rishi Sunak and former Prime Minister Boris Jonson are still years away from completion, a parliamentary report has revealed.

A report by the Commons Public Accounts Committee found that only £1.24 billion will be spent on the projects by the end of this month out of £10.47 billion programme originally promised by Johnson’s Government to improve dilapidated town high streets and run down areas of the country.

This month is supposed to be the completion of the first round of “Levelling Up” grants which councils had to put in bids under the scheme but the report reveals the deadline has had to be extended for at least a year because so few have been finished. The report reveals that out of 71 so-called “shovel ready” projects due to be completed this month, only 11 had been finished and the remaining 60 would not be completed until next year, if not later.

It also says only £3.7 billion out of the £10.7 billion has been allocated to councils by the ministry because the bidding procedure has been so complex and many councils have wasted council taxpayers money on projects which stood no chance of being accepted by ministers.

Ministers changed the rules midway through the bidding for Levelling Up projects so that councils that were successful in bidding in the first round were disqualified from bidding in the second. As a result 55 councils wasted scarce council taxpayer’s money by putting in bids that were ruled out.

Dame Meg Hillier MP, Labour Chair of the Committee, said: “The levels of delay that our report finds in one of Government’s flagship policy platforms is absolutely astonishing. The vast majority of Levelling Up projects that were successful in early rounds of funding are now being delivered late, with further delays likely baked in.

“DLUHC [The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities] appears to have been blinded by optimism in funding projects that were clearly anything but ‘shovel-ready’, at the expense of projects that could have made a real difference. We are further concerned, and surprised given the generational ambition of this agenda, that there appears to be no plan to evaluate success in the long-term.

The ministry tried to claim to the National Audit Office that the majority of the programme was under way but when MPs questioned civil servants from the department it was revealed that “under way” only meant that construction was at the design stage or required planning permission.

Both the Local Government Association, which represents local councils, and the South East Councils, which represents local authorities in London and the South East, were highly critical of the bidding process to get the money.

South East Councils described the process as a “whole system of “beauty contest bidding” [which] is bad government. Levelling up funding further contributes to a “begging bowl culture” through a wasteful, inefficient, bureaucratic, over-centralised, unpredictable, short-termist, demoralising, time-consuming and frustrating way of allocating money to councils.”

In the South East only four councils got any money – they were Gosport, Gravesham, Test Valley and the Isle of Wight.

Taxing the super-rich to save capitalism from itself

[Usual Caveat: AI Generated translation (with slight edits) of a piece written in Italian]

The distribution of income has become topical again in recent days, and it is likely going to be one of the issues that will characterize the debate on the global governance of the economy in the coming months.

First, U.S. President Joe Biden announced a plan to reduce public debt centered on raising the minimum corporate tax from 15% to 21%, and on a minimum income tax of 25% for billionaires. The announcement is especially significant because it was made in the traditional State of the Union address, a solemn moment that this year also marks the beginning of the election campaign for the November elections. It is no coincidence that Biden has decided to call on the super-rich and corporations, especially the largest, to contribute the most to public finances’ healing: they are in fact the two categories that have managed to offload most of the inflation of recent years on consumers, wages and the less well-off categories in general.

The plan is highly unlikely to become a reality in a Congress dominated by a radicalized Republican Party, united behind Donald Trump, and conservative Democrats. But its symbolic significance is important and makes it clear what interests the president intends to defend in the November elections. With this proposal, the Biden administration proves once again, at least as far as economic issues are concerned, to be the most progressive in recent decades, much more courageous in attempting to protect the middle classes than the iconic, but ultimately too timid, Barack Obama.

A minimum tax rate for the super-rich

The issue of tax justice, and this is the second piece of recent news, is also at the center of the agenda of Lula’s Brazilian government, which in 2024 holds the rotating presidency of the G20. The G20 is probably the most significant body today for the coordination of economic policies at the international level. It is therefore particularly significant that the idea of reintroducing more progressivity by taxing the super-rich, which is not new in itself, is being discussed there.

In front of the G20 finance ministers that were meeting in São Paulo, the Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman pleaded for a fairer global system, first of all insisting on how tax progressivity, being crucial for financing public goods such as health, education, infrastructure, is one of the pillars on which the growth and the social contract of well-functioning democracies are based. Second, documenting how the tax systems of most countries have, in recent decades, become fundamentally regressive, especially with regard to the few thousand super-rich that sit at the top of the income distribution. In France, for example, the poorest 10% of the population pays almost 50% of their income in taxes, while the super-rich pay less than a third (the figure is taken from the 2024 Global Tax Evasion Report).

The reasons for this aberration are well known: the unbridled rush of recent decades to fiscal dumping, the benefits offered by many countries to multinationals and higher income owners in an attempt to attract them, have created a multitude of tax niches and possibilities for the wealthier to structure their income and their fortune in such a way as to generate low or no taxable incomes.

Precisely to avoid fiscal competition between countries, which allows the wealthier (but also multinationals) to travel in search of tax havens, Zucman and others are pushing for a global solution, along the lines of the BEPS agreement reached at the OECD in 2021 on the taxation of multinationals. For this reason, the initiative of the Brazilian presidency and the decision of the G20 finance ministers to commission a report that goes into the details of the proposal are very good signs.

Beyond the details that will need to be worked on, crucial to avoid loopholes and avoidance, the proposal by Zucman the economists of the Tax Observatory he heads, on which the G20 will discuss in the coming months, is that of a minimum rate of taxation on the super-rich, designed taking as a model the aforementioned OECD agreement on the minimum rate for multinationals. Since income, for the reasons mentioned above, is very difficult to compute, the international community should agree that taxpayers pay at least a certain percentage of their wealth in income taxes (Zucman proposes 2%). The proposal has several advantages: (1) those who already pay high income taxes would not have any additional burden, while those with large wealth that manage to hide their income from the tax authorities (in a more or less legal way) would be called upon to pay. (2) in many countries there are already instruments for assessing wealth, which would therefore only need to be generalised and harmonised. (3) as with the minimum tax on multinationals, mechanisms can be devised to discourage the relocation of wealth to countries that decide not to cooperate. (4) even with just a low rate like the one proposed by Zucman, it would be possible to obtain tax revenues of hundreds of billions a year, which are needed above all by the poorest countries to finance welfare, ecological transition, and infrastructure for growth.

Last, but certainly not least, being able to get the richest to contribute to the common good would help at least in part to restore the sense of justice and trust in the social contract that has progressively eroded in recent decades. As Zucman concludes in his address to the G20 ministers, “Such an agreement would be in the interest of all economic actors, even the taxpayers involved. Because what is at stake is not only the dynamic of global inequality: it is the very social sustainability of globalization, from which the wealthy benefit so much.”

The conservative revolutions of the early 1980s ushered in an era in which the watchword was simply “get as rich as you can and think only of yourself” (exemplified by Gordon Gekko’s praise of greed in Oliver Stone’s masterful Wall Street). That era did not bring us the promised prosperity or stability. On the contrary, we now live in sick democracies, unstable economies characterized by intolerable levels of rent seeking and inequality. In the 1930s, one of Keynes’s goals in pleading for an active role of the government was to save capitalism, in crisis and threatened by the rise of the Soviet Union. The many who are in love with the supposed Great Moderation of the 1980s and 1990s stubbornly opposing all attempts to correct excessive inequality, should think twice. Instead, they should endorse wholeheartedly attempts such as that of the G20 Brazilian presidency to save capitalism above all from its internal enemies, far more dangerous than the external ones.

Economic Memories and Sense-making of the Profound Institutional Change

by Till Hilmar* My recent book Deserved reconstructs people’s experiences with, and memories of, disruptive economic change. It foregrounds the voices of individuals who endured the “shock therapy” of the 1990s – the transition from communism to market society – in two societies.The analysis is driven by a historical-comparative argument: Before 1989, East Germany and […]

The Yeats sisters: a magnificent celebration

I watched Imelda May’s fascinating programme on Sky Arts last night, in which she explored the story of the Yeats sisters, Elizabeth and Susan, who were usually known as Lolly and Lily.

Now apparently (and certainly to me) unknown, they were the sisters of the Irish poet, William Butler Yeats. They were profoundly influential in his life, not least, because they printed and published the first editions of many of his works through their Dublin based Cuala Press.

I was pleased that both their father and brothers made only peripheral appearances in this programme. It was, rightly, a celebration of two profoundly intelligent and diligent women who through their work had a major impact on the arts and crafts movement in Ireland, and beyond, in the period from 1900 to 1940.

Lily Yeats’ work as an embroiderer and artist was displayed, and it was truly magnificent, especially (in my opinion) when she avoided people and animals and instead celebrated the landscape.

What, however, truly fascinated me was the work of the Press itself .

I love letter press printing. There is something extraordinarily powerful about this form of creation, which becomes art in itself.

What I do, have to admit, though is that the love in question is the result of an idea that I have held dear since I was a teenager. That is that a person possessed of an idea, the means to put it on paper, and a mechanism to reproduce it has the most powerful possible tool to influence the world in which they live. I have never changed my belief about this and I know that my fascination with writing and everything to do with its recreation will, for me, never end. I did in that sense feel a very powerful affinity with what Lolly Yeats, in particular, was doing with the Cuala press.

The fact that they first published so many of the writers whose work I absorbed in my twenties and thirties when I was seeking to understand Ireland, its history, its independence and the movement that eventually delivered that freedom was something of which I was not previously aware. That left me both enthused, and a little annoyed. That these sisters’ role went unacknowledged whilst their brother is so well-known is such a powerful symbol of cultural oppression, and makes the point that International Women’s Day, which this programme marked, is still deeply relevant.

It also helps that I am an enormous fan of Imelda May’s work that now exist in an increasing variety of forms. She is herself a force of nature, willing to take the risk to say things that others know, but are not willing to express. She was the right person to explore the Yeats sisters’ courage, and her enthusiasm was both obvious and very genuine.

I have been writing with the intention of seeing my words in print since my early teenage years. The roles of the publisher, editor, designer and printer are too often ignored in all of that process. Last night’s programme was a true celebration of two exceptional sisters and I am delighted to have watched it. It was great work by all involved.

Introducing the Salary Cap Act

by Daniel Wortel-London

Obscene salaries are no longer sustainable and should be illegal. (Justin Pacheco, Wikimedia)

The daily news regularly features commentary about the outrageous and growing income inequality in the USA. The data support the outrage:

- In 1965, the CEO-to-worker salary ratio at the average U.S. company was 21-to-1. Today that ratio is 344-to-1.

- In 2022, CEO pay at 100 S&P 500 companies averaged $15.3 million, while median worker pay averaged only $31, 672, according to an Institute of Policy Studies analysis.

- Since 1978, CEO pay has increased 1,460 percent.

Many reasons can be cited for opposing large discrepancies in pay, including depressed morale of employees, diminished firm productivity, and widened gender and racial disparities. Another reason is their effect on the environment. High salaries tend to increase environmental impacts. And high pay, particularly high CEO pay, is dependent on—but also drives—the economic growth that is creating today’s societal and environmental crises.

To counter inequality in the USA, CASSE proposes adoption of a Salary Cap Act (SCA). The Act would create salary caps by major occupational sector, as Brian Czech proposed in Supply Shock. Almost no expansion of the Tax Code is entailed. The SCA would simply prohibit the issuance of salaries beyond the prescribed proportions (described below), making it a crime for employers to issue exorbitant salaries.

Exorbitant Salaries and Environmental Degradation

Generating money entails agricultural and extractive activity at the trophic base of the economy. Therefore, the need to pay exorbitant salaries results in more environmental degradation than paying for lesser salaries. Imagine, for example, the ecological footprint required to pay Elon Musk compared to a minimum-wage worker.

Highly paid individuals are more likely to purchase resource-intensive luxury goods, too. This is one reason why the USA’s top one percent of income earners was responsible for 23 percent of the growth in global carbon emissions between 1990 and 2019. And income inequality leads to inequality in political power, which helps CEOs lobby for policies that promote unsustainable growth.

Limiting the environmental impact of the economy entails limits on high salaries. (Richard Hurd, Creative Commons 3.0)

High salaries drive growth in less obvious ways as well. At many corporations, CEO compensation includes a generous grant of stock and stock options. These sweeteners motivate CEOs to strive for company growth, then use profits to buy back company stock, which raises its price and enriches the CEO even further.

For example, the compensation of oil company executives is intimately linked to exploring for new fields, extracting fossil fuels, and promoting consumption of their fuels and services, activities that contribute to the growth of the firm. As Richard Heede of the Climate Accountability Institute observes, “executives have personal ownership of tens or hundreds of thousands of shares, which creates an unacknowledged personal desire to explore, extract and sell fossil fuels.”

Moreover, high CEO compensation through stock options and bonuses encourages companies to take a short-term perspective that can involve boosting stock prices quickly through shortsighted sales or risky investments. The Enron scandal, for example, involved CEOs trying to quickly raise stock prices in pursuit of bonuses. Selfish and short-sighted decisions like these can take a serious environmental toll, and are disastrous at a time when companies should be committed to the long-term health of our planet.

Drivers of Unequal Pay

CEO pay has increased extensively in part because companies have grown larger and wealthier, which allows them to offer fatter salaries. It’s also because CEOs have increased their leverage over corporate boards and can therefore set their own pay more easily. But the greatest reason is because CEOs are compensated differently than ordinary workers: Some 80 percent of CEO compensation in 2021, for example, derived from vested stock awards and exercised stock options rather than “ordinary” salaries. CEOs are thus able to negotiate salaries that are orders of magnitude higher than the salaries of workers paid through more conventional means.

Policymakers have a deep toolbox for addressing pay inequality. They can, for example, ban or tax stock buybacks or deny public contracts to companies with excessively high pay inequalities. Measures like these are now law. The Inflation Reduction Act placed a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks, while San Francisco and Portland, Oregon have taxed companies with large CEO-worker pay gaps. Inspiration comes from outside the USA as well. The European Union will assist in bailing out failed banks only when their pay ratios are 10-to-1 or less.

Franklin Roosevelt called for a 100 percent tax on annual incomes above $1.2 million (in 2022 dollars). (Elias Goldensky, Public Domain).

But another, more direct remedy for pay inequality is salary caps. We’ve seen such caps in professional sports leagues for decades, including every major league in the USA except Major League Baseball. These caps are much higher than those prescribed in the Salary Cap Act presented below, but they achieve analogous purposes. Leagues use caps to keep overall costs down and ensure a competitive balance among teams. The USA would use salary caps to for purposes of social equity, but also to keep environmental impact at a lower, more sustainable level.

Salary caps, along with caps on wealth and other forms of income, have been proposed by various economists and progressive policymakers, occasionally with public success. A referendum was held in Switzerland in 2013 to cap executive incomes; while unsuccessful, it emboldened major candidates in France and England to endorse similar salary caps. And campaigns for wealth and income caps have taken various forms in U.S. history, from Huey Long’s “Share our Wealth” campaign to Franklin Roosevelt’s call for a 100 percent tax on high incomes during World War II.

In the spirit of these efforts, CASSE proposes the Salary Cap Act.

The Salary Cap Act

The Salary Cap Act is designed to curb exorbitant salaries for purposes of social equity and environmental health. Salary caps are set and enforced by the Department of Labor. A separate provision addresses pay for self-employed workers.

The SCA defines “salaries” as wages, bonuses, tips, and other forms of compensation specified under Section 3401(a) of the Internal Revenue Code. This broad definition is meant to encompass forms of compensation, such as corporate stock options, which are not traditionally classified as “salaries.”

Section 4 describes the target and structure of the salary caps. The Secretary of Labor sets the caps for each of the 23 major occupational groupings in the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) Codes maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The caps are set, and updated annually, to correspond to 1.8 times the salary of the 90th percentile of employees for each occupational grouping. (In other words, maximum salaries in each occupational grouping are 80 percent higher than the salary at which 90 percent of salaries in the grouping are lower and ten percent are higher.)

For example, the annual salary cap for managerial occupations would be set at $400,000, while the cap for food preparation occupations would be set at $81,270. Salary disparities would remain, but they would be far lower than the disparity today. The average CEO-to-worker pay gap across occupational categories is currently 344-to-1. Under the SCA, the ratio would be roughly 7-to-1.

We can respect planetary boundaries, or we can have billionaires, but not both. (Adrian Cadiz, Wikimedia)

Meanwhile, traditional and reasonable salary discrepancies among professions are still respected. For example, licensable occupations that require extensive training or years of graduate school warrant a higher range of salaries than those for occupations requiring little training or education.

The value of 1.8 in the maximum salary formula is chosen because the salary of the President of the United States is currently 1.8 times the 90th percentile of CEO salaries. We do not believe a CEO deserves to be paid more than the president. Still, the SCA’s maximum salary formula offers plenty of room to reward superior performance while curbing the social and environmental distortions of exorbitant salaries.

Section 5 describes how the Office of Labor-Management Studies in the Department of Labor will enforce the SCA. The Office will have the power to petition a court if it believes the Act has been violated. Companies found guilty will face criminal penalties of up to $100,000,000, imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, or both.

A concluding section requires net earnings from self-employment or employee ownership in excess of $400,000 be taxed at 100 percent. Salaries derived from self-employment are not included in the NAICS SOC codes, so it is necessary to “cap” these earnings through taxation rather than salary caps.

The SCA is designed to be both a stand-alone bill and a component of the larger Steady State Economy Act. It will not, by itself, end wealth inequality or ecological overshoot. But it will help apply brakes on incentives that drive economic firms to grow the economy beyond our planet’s carrying capacity.

We also encourage the voluntary adoption of salary caps prior to passage of the SCA. In addition to contributing to the social and environmental purposes of the SCA, such voluntary caps provide a boost to employee morale and cut costs for small businesses and nonprofit organizations.

The Salary Cap Act may be revised pursuant to reader responses and the input of CASSE allies.

Daniel Wortel-London is a CASSE Policy Specialist focused on steady-state policy development.

The post Introducing the Salary Cap Act appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Cartoon: Floored

I was in DC giving this speech at the National Press Foundation awards dinner.

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

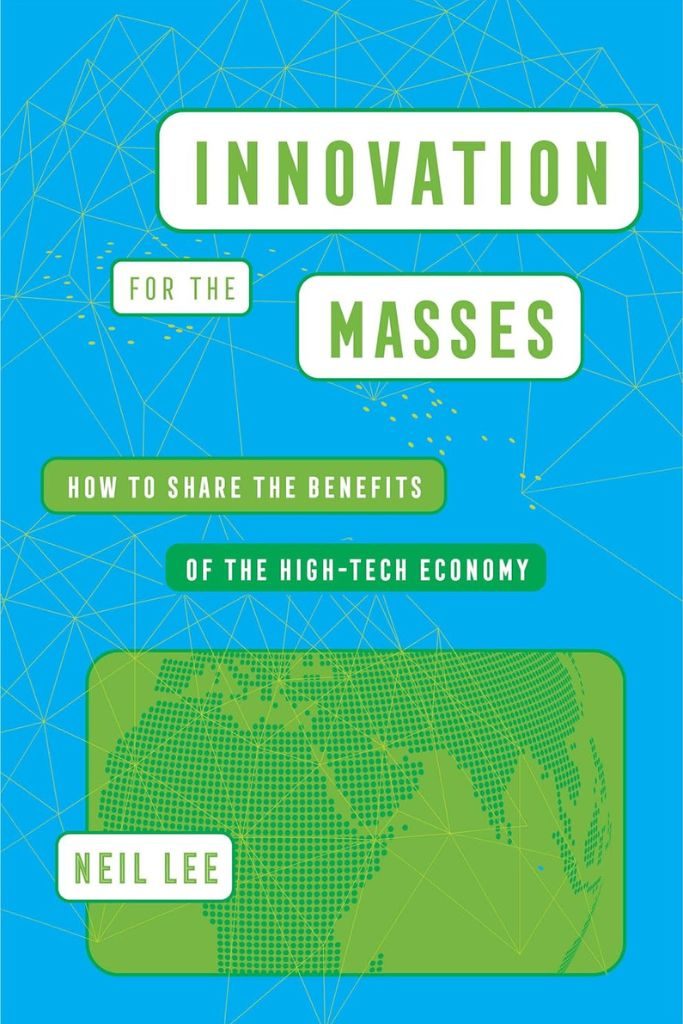

Innovation for the Masses: How to Share the Benefits of the High-Tech Economy – review

In Innovation for the Masses: How to Share the Benefits of the High-Tech Economy, Neil Lee proposes abandoning the Silicon Valley-style innovation hub, which concentrates its wealth, for alternative, more equitable models. Emphasising the role of the state and the need for adaptive approaches, Lee makes a nuanced and convincing case for reimagining how we “do” innovation to benefit the masses, writes Yulu Pi.

Professor Neil Lee will be speaking at an LSE panel event, How can we tackle inequalities through British public policy? on Tuesday 5 March at 6.30pm. Find details on how to attend here.

While everyone is talking about AI innovations, Innovation for the Masses: How to Share the Benefits of the High-Tech Economy arrives as a timely and critical examination of innovation itself. Challenging the conventional view of Silicon Valley as the paradigm for innovation, the book seeks answers on how the benefits of innovations can be broadly shared across society.

While everyone is talking about AI innovations, Innovation for the Masses: How to Share the Benefits of the High-Tech Economy arrives as a timely and critical examination of innovation itself. Challenging the conventional view of Silicon Valley as the paradigm for innovation, the book seeks answers on how the benefits of innovations can be broadly shared across society.

When we talk about innovation, we often picture genius scientists from prestigious universities or tech giants creating radical technologies in million-dollar labs. But in his book, Neil Lee, Professor of Economic Geography at The London School of Economics and Political Science, tells us there is more to it. He suggests that our obsession with cutting-edge innovations and idolisation of superstar hubs like Silicon Valley and Oxbridge hinders better ways to link innovation with shared prosperity.

Lee stresses that innovation doesn’t make a difference if it stays locked up in labs; it needs to be shared, learned, improved and used to make real impacts.

Innovation goes beyond the invention of disruptive new technologies. It also involves improving existing technologies or merging them to generate new innovations. In this book, Lee illustrates this idea using mobile payment technologies as an example, showcasing how the combination of existing technologies – mobile phone and payment terminals – can spawn new innovations. He argues that “technologies evolve through incremental innovations in regular and occasionally larger leaps” (23). Moreover, Lee stresses that innovation doesn’t make a difference if it stays locked up in labs; it needs to be shared, learned, improved and used to make real impacts. It is important to think beyond the notion of a single radical invention and recognise the contributions not only of major inventors but of “tweakers” who make incremental improvements and implementers who operate and maintain innovative products (25).

In challenging the conventional narratives of innovation, this book guides us to expand our understanding of innovation and paves the way for a discussion on combining innovation with equity. When we pose the question “How do we foster innovations?”, we miss out on asking a crucial follow-up: “How do we foster innovations that translate into increased living standards for everyone?”. Lee argues that the incomplete line of questioning inevitably steers us towards flawed solutions – countries all over the world building their own Silicon-something.

While the San Francisco Bay Area is home to many successful start-up founders who have made billions, it simultaneously struggles with issues like severe homelessness.

While the San Francisco Bay Area is home to many successful start-up founders who have made billions, it simultaneously struggles with issues like severe homelessness. The staggering wealth gap is evident, with the top 1 per cent of households holding 48 times more wealth than the bottom 50 per cent. Other centres of innovation like Oxbridge and Shanghai are also highly unequal, with the benefits of innovations going to a small few.

The book introduces four alternative models of innovation – Switzerland, Sweden, Austria and Taiwan – that suggest innovation doesn’t inevitably coincide with high-level inequality.

The book introduces four alternative models of innovation – Switzerland, Sweden, Austria and Taiwan – that suggest innovation doesn’t inevitably coincide with high-level inequality. Through these examples, Lee highlights the significance of often-neglected aspects of innovation: adoption, diffusion and incremental improvements. Take Austria, for instance, which might not immediately come to mind as a global hub of disruptive innovation. Its strategic commitment to continuous innovation – particularly in its traditional, industrial sectors like steel and paper – sheds light on the more nuanced, yet equally impactful, facets of innovation. (92) Taiwan, on the other hand, gained its growth from technological development facilitated by its advanced research institutions such as the Industrial Technology Research Institute and state-led industrial policy. Foxconn stands as the world’s fourth-largest technology company, while the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) accounts for half of the world’s chip production (116).

In all four examples, the state played a critical role in creating frameworks to ensure that benefits are broadly shared, showing that policies on innovation and mutual prosperity reinforce each other.

Building on these examples, the book highlights the vital role of the state in both spurring innovations and distributing the benefits of innovation. In all four examples, the state played a critical role in creating frameworks to ensure that benefits are broadly shared, showing that policies on innovation and mutual prosperity reinforce each other. Taking another look at Austria, ranked 17th in the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)’s Global Innovation Index (99), its strength on innovation is accompanied by the state’s heavy investment on welfare to build a strong social safety net.

As the book draws to a close, it advocates for the development of a set of specific institutions. The first type, generative institutions, foster the development of radical innovations. These are heavily funded in the US, resulting, as British economist David Soskice claims, in the US dominance in cutting-edge technologies (169). The book shows a wide array of generative institutions through its four examples. For instance, in Taiwan, research laboratories play a crucial role in the success of its cutting-edge chip manufacturing, while the government directs financial resources towards facilitating job creation. On the other hand, Austria has concentrated its fast-growing R&D spending on the upgrading and specialisation of its low-tech industries of the past.

The second and third types, diffusive and redistributive institutions, aim to address issues of inequality, such as labour market polarisation and wealth concentration that might come with innovation. These two types of institutions offer people the opportunity to participate in the delivery, adoption and improvement of innovation. Switzerland’s mature vocational education system is a prime example of such institutions, “facilitating innovation and the diffusion of technology from elsewhere and ensuring that workers benefit.” (172)

Discussions about ‘good inequality’ where innovators are rewarded, and “bad inequality,” where wealth becomes too concentrated demonstrate the book’s strong willingness to call out inequality and tackle complex issues head-on.

Discussions about “good inequality” where innovators are rewarded, and “bad inequality,” where wealth becomes too concentrated demonstrate the book’s strong willingness to call out inequality and tackle complex issues head-on. (8) This integrity extends to Lee’s candid examination of the examples. Despite presenting them as models of how innovation can be paired with equity, he does not gloss over their imperfections. By recognising the persistent disparities in gender, race, and immigration status in all four of these examples, the book presents a balanced narrative that urges readers to think critically. Although these countries have made strides in sharing the benefits of innovation, they are far from perfect and still have a significant journey ahead to reduce these disparities. Take Switzerland, for example. Though it consistently tops the WIPO’s Global Innovation Index, maintaining its position for the 13th consecutive year in 2023, it grapples with one of the largest gender pay gaps in Europe. This gender inequality has deep roots, as it wasn’t until 1971 that women gained the right to vote in Swiss federal elections (71).

Lee warns against the naive replication of these success stories elsewhere without adapting them to the specific context. This frank and thorough approach enriches the conversation about innovation and inequality, making it a compelling and credible contribution to the discourse and a convincing argument for changing what we consider to be the purpose of innovation.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: vic josh on Shutterstock.

People in North of England ‘Live Shorter, Sicker, Poorer Lives Simply Because of Where They Were Born’

People living in the north of England will take nearly a lifetime to reach the same healthy life expectancy as those living now in the prosperous south-east, a damning report reveals today.

The IPPR North think tank has found that it will take 55 years, until 2080, for those living in the north-east of England to have the same healthy life expectancy now enjoyed in London and the south-east of England.

It calls for a radical change in funding for local government and a decade of renewal to change this trajectory, warning "only bold and concerted action will change the course of England’s regional divides”.

The report shows the Government’s current 'levelling up’ programme is inadequate because it is undermined by the scale of local government cuts, and that regional wealth inequality will continue to grow.

IPPR North calls for a reform of capital gains tax to fund investment in the regions, as well as action to stave off political cynicism, investment to halt the collapse of local authority finances, and renewed urgency in the creation of good jobs as part of a renewed regional agenda.

The report also provides some startling facts showing that the level of inequality in the UK – citing examples which Byline Times also analysed in its March 2024 print edition – of the differences between wealth and health in Blackpool and the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

The report cites that in Blackpool – which has the lowest male life expectancy in England – a man has the same healthy life expectancy as in Turkey, a far poorer country than the UK.

While “one neighbourhood of 6,400 people in Kensington had as much in capital gains as Liverpool, Manchester, and Newcastle combined while Kensington's overall share of UK capital gains was greater than all of Wales”.

The situation is likely to get worse, by 2030, before it can get any better – posing a huge challenge for a potential incoming Labour government.

Life expectancy is expected to drop further in the north-east, East Midlands and the east of England while continuing to rise in London and the south-east by 2028 to 2030.

Spending by local government has fallen drastically since 2009 to 2010 – especially in urban areas. Taking all locally controlled spending power together, the average local government district area has seen a fall of £1,307 per head of population in real terms. Between now and 2030 it is expected to fall further.

Wealth inequality is on course to grow, with a gap reaching £228,800 per head between the south-east and the north by the end of the decade, on current trends.

Opportunities for good jobs also divide the north and London. By 2030, London will have a 66% employment rate compared to just under 56% for the north-east, the report states.

IPPR North research fellow and the report's author, Marcus Johns, said: “No one should be condemned to live a shorter, sicker, less fulfilling, or poorer life simply because of where they were born.

"Yet, that is what our regional inequalities offer today as gaps in healthy life expectancy and wealth endure over the generations, demanding urgent action if we are to change course.

“It’s hard to avoid the conclusion we are headed in the wrong direction on inequality in health, wealth, power, and opportunity while local government finances languish in chaos.”

Unless we put the UK’s wealth to work for social purposes we really are in very deep trouble

I have noted a report in the Guardian this morning which suggests that Southwark Council is seeking to raise £6 million of crowd-sourced funding over the next six years, which it will use to fund climate change-related investments in its borough. It is offering to pay 4.6% interest on the sums it is borrowing at present, which is a lower rate than it would have to pay HM Treasury to borrow the same money. It is, apparently, one of nine councils undertaking such arrangements at present and secured £50,000 of funding within hours of its new scheme being open.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that I find much to applaud in this arrangement, albeit that I despair at the current approach adopted by HM Treasury, which is penalising councils for seeking to borrow to achieve such vital objectives. Twenty-one years ago, Colin Hines and I wrote our first ever report, working with Alan Simpson, who was a Labour MP at the time. It was called People’s Pensions and was published by the New Economics Foundation. It suggested that pension savings should be turned into the capital required by local authorities and other public administrations to fund the investment required in their communities. Local authority bonds were to be the instrument of choice for this radical transformation.

I have never given this theme up. We live in a country where there is reported to be £8,100 billion of financial wealth and a simultaneous desperate shortage of investment. That is because almost none of that financial wealth represents sums actually available for constructive use within the economy. It is instead either money sitting out of circulation in bank accounts or sums saved for speculative purposes, much of it represented by the ownership of shares in quoted companies or the ownership of second-hand buildings.

The old economic idea that saving had anything to do with investment, which claim provides the logic for the UK government still giving £70 billion of tax relief to those saving money into economically dormant or socially useless ISA or pension accounts, has been shattered in a wholly financialised economy where doing something as unseemly as actually using saved funds to provide capital for real economic activity never appears to occur to anyone in so-called financial markets.

I applaud Southwark for trying to re-establish this relationship between a saver and the constructive use of capital within a local economy. It is entirely appropriate.

What I find disheartening is that those saving in this way will not enjoy a government guarantee on the funds that they make available to Southwark when that guarantee would be provided if they put the money, uselessly, into a bank deposit account.

What I also find unacceptable is the fact that this proactive funding will not enjoy the tax subsidy that either ISAs or pension investments do.

That is precisely why I have suggested that in future, all existing types of ISA accounts should be withdrawn and the only option available for those wishing to save an ISAs should be that the funds in question be used to invest in the green economy, either by buying bonds to be issued by a Green National Investment Bank, the return on which would carry an implicit government guarantee, or by investment in shares and bonds issued by banks, public or private companies, all of which would be required to prove that the money that they had entrusted to them was used to provide capital for investment in new economic activity intended to assist the UK’s transition to becoming a net – zero economy.

I have also, repeatedly, over 21 years, suggested that part of all new pension contributions should be used for the same purpose as a condition of the tax relief provided on such sums to those making pension contributions.

Currently, £70 billion a year goes into ISA accounts and sums well in excess of 100 billion go into pension arrangements. The combined cost of tax relief on these sums is £70 billion a year, a figure in excess of the UK defence budget. In exchange, there is no obvious return of any sort to society, but enormous benefit does arise to the city of London and to those who are already wealthy, who are the inevitable beneficiaries of this largesse from the state, which they zealously seek to preserve whilst criticising all those who claim any form of benefit.

Until we join up the obvious dots in the economy and require that savings be reacquainted with investment and that tax relief only be associated with the achievement of a social purpose, we are not going to tackle the immediate issues that plague us, whether they be a shortage of gainful employment, massive under-employment, a lack of investment, or our failure to tackle the climate crisis. Rebuilding the relationship between saving and investment in a way that tackles all these issues is an obvious way to go forward, but to date no political party has shown willingness to adopt this approach, which I find deeply discouraging. However, Southwark and other councils do appear to be showing the way. I welcome that. The rest of the country needs to follow the path that they are blazing the way because unless we put the UK’s wealth to work for social purposes we really are in very deep trouble.