inequality

The government’s deliberate policy of prejudicing the poorest in our society is imposing destitution on millions

A number of related themes are apparent in commentary on the economy this morning.

One is poverty. As the Guardian notes:

Millions of people – including one in five families with children – have gone hungry or skipped meals in recent weeks because they could not regularly afford to buy groceries, according to new food insecurity data.

According to the Food Foundation tracker, 15% of UK households – equivalent to approximately 8 million adults and 3 million children – experienced food insecurity in January, as high food prices continued to hit the pockets of low-income families.

This is a tale of destiution and misery in the UK.

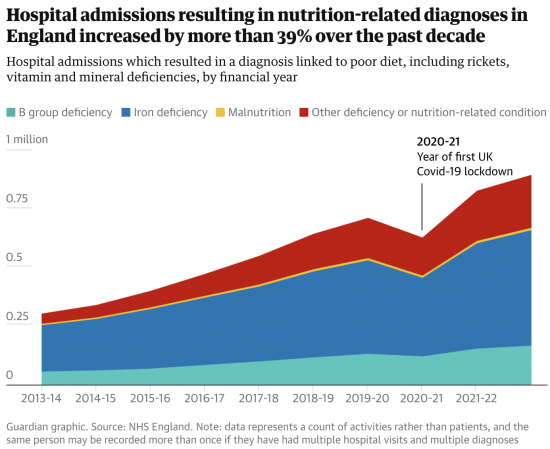

They add this graph:

We have a health crisis not just caused by Covid (although that is still very real) but by the existence of poverty thanks to George Osborne and successive subsequent Tory Chancellors, soon the be perpetuated by Rachel Reeves. That crisis is not just personal; it is collective in its cost.

Then there is this in the FT:

A lack of available loans from traditional UK lenders is pushing vulnerable consumers towards unregulated credit products as they struggle financially in the cost of living crisis, according to a study.

The UK nonprime lending market — which offers loans to riskier customers with average to low credit scores — has shrunk by more than a third since 2019.

In contrast, unsecured loans from unregulated lenders, such as those offering buy now, pay later (BNPL) products, have jumped in recent years, according to research from credit-checking platform ClearScore and consultancy EY.

The result is that the most vulnerable people in the UK who need to borrow to meet unexpected costs because they have little, or usually no, savings are being forced into the highest cost, most abusive, arrangements. It was this concern that motivated a post I made yesterday: you would never have known it from the comments of the right-wing trolls who poured in during the day to offer abuse, and who got deleted for their efforts.

And finally, there is this, also in the FT but reported in a remarkably similar style in the Guardian:

Jeremy Hunt’s financial planning is “dubious” and “lacks credibility” and the chancellor should not announce tax cuts in next week’s budget if he cannot lay out how he will fund them, an economic thinktank has said.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) calculates that Hunt would need to find £35bn of cuts from already threadbare public services if he plans to use a Whitehall spending freeze to pay for pre-election giveaways.

A fresh round of austerity in unprotected departments would boost the chancellor’s war chest for tax cuts, the independent tax and spending watchdog said, but an increase from an expected £15bn of headroom to about £50bn over the next five years would come at a high cost.

That cost will, in very large part, be seen in the perpetuation of poverty. The lowest paid will suffer tax rises. They will have the services that they need cut. The NHS, social care and housing will not be properly funded. Education, that was the route out of this, is unable to meet need. And benefit increases have not met inflation-hiked prices for basic commodities. And Hunt wants to make all of this worse.

A government unable to admit that there is Islamophobia in its rank hopes that rows on that issue will distract attention from another pressing concern, which is that its deliberate policy of prejudicing the poorest in our society is imposing destitution on millions and relative poverty on us all because of the opportunities lost to the communities in which we all live.

The upward redistribution of wealth

Investment advisers Hargreaves Lansdown issued a press release this morning saying:

Debts cost an average of £406 a month – as arrears mount

-

The average household spends £406 on monthly debt repayments, excluding the mortgage. Those with mortgages spend an average of £814 on top of this.

-

Almost one in ten households (9%) are in arrears. Among the lowest fifth of earners this rises to 27%.

-

One in five people are concerned about their debt position.

-

Credit card debt is up 12.7% in a year to £68.9 billion and other consumer debt (including loans, overdrafts and car finance) is up 6.7% to £150.4 billion (Bank of England).

The arrears data worries me, as does the increase in credit. But so too does the bigger picture.

There are about 27 million households in the UK. Around £132 billion is being paid by those households a year to service debt interest, exclusion mortgage costs. That is a staggering upward annual redistribution of wealth. And you wonder why I want interest rates to be as low as possible? That’s the reason why. Those without wealth are being exploited by those with it, and that is a recipe for an unstable society, which is exactly where we are heading.

On ‘Alternative Walking Tours,’ Formerly Homeless People Share Their Perspectives

After struggling with alcohol addiction for over 10 years — during which his 20-year banking career and 30-year marriage both collapsed — it was a presentation in a rehab center in 2019 that became the catalyst for Miles to turn his life around.

The presentation was by Invisible Cities, an organization which, since its inception in 2016, has trained 118 formerly homeless people to become tour guides. It’s a creative way of giving them not only a new income stream, but also a new sense of purpose — and skillset, too.

“This helped fill a void after I finished rehab,” says Miles, who has withheld his name for privacy reasons. “This was the opportunity that first helped me back on to a path of a ‘normal’ life again, and having a purpose.”

It took Miles six months to put together his tour of York. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

It took Miles six months to put together his tour of York. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

“I probably wouldn’t be where I am today without the opportunity Invisible Cities gave me. I’ll always be grateful for that.”

Invisible Cities’ guides specialize in unique topics that reflect their own personal story — such as a city’s LGBTQI history, notable women, protest culture, ties to witchcraft or how crime and punishment has evolved — in the UK cities of Edinburgh, York, Cardiff, Glasgow and Manchester.

Invisible Cities provides training for guides to create these “alternative walking tours,” as well as in public speaking and customer service skills. The organization is then responsible for marketing the tours and taking bookings. Participants pay up to £15 (around $19 US), which is split between the guide and Invisible Cities to support their efforts in recruiting more guides who have experienced homelessness.

An Invisible Cities guide regales visitors on a tour in Manchester. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

An Invisible Cities guide regales visitors on a tour in Manchester. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

Invisible Cities has also set up a grant program for guides to access funding to do other external courses or start their own business, and offers training in IT and presentation skills to help them gain further employment.

With the help of sponsors, Invisible Cities also offers free community tours for specific groups. In 2023, 569 people from the Ukrainian community and from underprivileged areas attended free tours.

Miles’ tour of the English city of York, in which he has lived for the past 30 years, took him six months to put together. During that time, he transitioned out of the rehab center and into resettlement housing, where he stayed until he moved into his own apartment in 2021.

On his tours, Miles focuses on health and wealth in York, in parallel with his own experience in which his health was compromised due to addiction, and both having and losing wealth. He highlights buildings that have brought either health or wealth to the area, such as St. Leonard’s Hospital, which was one of the first hospitals in the UK, built in medieval times.

Courtesy of Invisible Cities

“This helped fill a void after I finished rehab. This was the opportunity that first helped me back on to a path of a ‘normal’ life again, and having a purpose.”

–Miles, Invisible Cities guide

He also spotlights the city’s chocolate making locations, from the Terry’s Chocolate factory, which manufactured the iconic “chocolate orange” that is a tradition to give and eat at Christmas in the UK, to the Rowntree’s site that created the popular Kit Kat chocolate bar.

“What Terry’s did is they brought employment into the city. But they recognised very early that in order to build their company, they had to provide housing for their staff, and they reinvested their original profits back into their workforce, and into building up the factory,” Miles explains.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

“And the same with Rowntree’s, who provided health benefits and housing to their workforce. But Rowntree’s was then taken over by Nestle, a multinational conglomerate, whose profits and investment go out of the city.”

Miles’ tours have evolved over the past five years based on social developments in the city and the questions participants ask. For example, his tours have addressed issues such as gang-related drug dealing, and a lack of accessible parking in the city, and he also weaves in his own experience living with addiction.

An Invisible Cities tour in York. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

An Invisible Cities tour in York. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

“I love being able to share the underbelly of our city, because York is very much seen as a vibrant city that’s rich with history and architecture. But I bring in aspects of rough sleeping, addiction and recovery, and I share what’s actually going on when [it’s] relevant, which keeps it alive for me, because it’s ever-changing,” he says.

Through other volunteering Miles has also built relationships with universities in the area, which have made his tour part of the curriculum for social policy students. He’s even had doctors come along who say they’ve gotten more out of it, in terms of understanding the city’s social support structure for homelessness and addiction, than a formal training day, so he is in talks with a number of local clinics to encourage more medical professionals to attend.

Founder Zakia Moulaoui Guery initially came up with the idea to help formerly homeless people gain the confidence to embrace the next chapter of their lives. To spread the concept of Invisible Cities further across the country, Moulaoui Guery has since developed a social franchise model, partnering with existing homeless organizations, which then take on the recruiting and training of guides.

This is crucial, says Moulaoui Guery, so the operation can continue to expand in a way that stays true to its mission of leveraging tourism to shine a light on issues of social justice and inequality, and help do good with the money visitors bring to iconic UK cities. Invisible Cities Cardiff, for example, is in partnership with The Wallach, the largest homelessness charity in Wales.

Courtesy of Invisible Cities

Invisible Cities guides are trained to give unique tours that weave together the city's history and their own personal story.

“Finding the right partner on the ground is always more important than whether or not that city will work in a touristic way,” says Moulaoui Guery. “I would rather work with a trusted partner, and for it to be a bit harder in terms of visitors, than to go somewhere like London, for example, which would be a lot harder to make work.”

In this way, expansion to Liverpool and the Scottish Borders is currently in the works. Moulaoui Guery is also eyeing cities like Oxford, Cambridge, Aberdeen and Dundee.

Not all who take on Invisible Cities’ training become guides — just 16 are currently actively running tours. About a quarter of a training cohort of around eight people become guides, shares Moulaoui Guery, while another quarter stay involved with Invisible Cities in a different capacity, for example, helping at tourism trade shows. Another quarter take up a different opportunity, through a job or setting up their own venture. And another quarter move on without staying in touch.

Zakia Moulaoui Guery, founder of Invisible Cities. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

Zakia Moulaoui Guery, founder of Invisible Cities. Courtesy of Invisible Cities

As much as she’s passionate about spreading the Invisible Cities movement, Moulaoui Guery is just as happy when guides move on.

“I think sometimes it’s great when we don’t hear anything from people, because it means they are moving on, and are too busy living out their dreams. What we don’t want to do is hold onto people forever,” she says.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Miles, meanwhile, is not only sober and in his own apartment, but has also helped set up another nonprofit organization to tackle homelessness and poverty. In light of his new commitments, he has gone from doing several Invisible Cities tours a week to a handful a month — but is keen to stay active as a guide even in this capacity.

“I don’t want to stop doing the tours,” he says. “They are really enjoyable. I will still keep this as a precious thing, because we are a close-knit team and really support each other. There’s quite a family feel.”

The post On ‘Alternative Walking Tours,’ Formerly Homeless People Share Their Perspectives appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

We desperately need a Green New Deal and our power elites would rather ignore that fact

As the Guardian's morning comment newsletter says in its introduction this morning:

Houses in the UK are some of the oldest and least energy efficient in Europe. A new report by Friends of the Earth and the Institute of Health Equity found that 9.6m households are living in cold, poorly insulated homes. These households also have incomes below the minimum for a decent standard of living, meaning that they cannot afford to install double glazing or insulation, for example, to make their homes warmer. The analysis comes just weeks after the Labour party U-turned on a key climate proposal, which included a pledge to insulate millions of homes. Meanwhile, over the last 13 years the government has reversed plenty of policies designed to tackle the insulation problem in the UK.

It's now more than fifteen years since I co-authored the first Green New Deal report. In that report, we called for the release of a 'carbon army' of well-trained people who could insulate Britain, install solar power and build the transmission networks for a new economy. There would be long-term employment on offer as a result. The UK would go green. And energy poverty would be tackled. It was an all-round win.

It has not happened.

Labour has now turned its back on the idea.

But we need this solution more than ever.

And it could be done. The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 shows that the funding is available. All that is lacking is the will.

Rather than tackle gross tax, income and wealth inequality in the UK, both our leading political parties would rather balance the government's books, subject us to the desires of the City of London and maintain the existing hierarchies of financial power within our society, which leave millions in poverty whilst denying us a future.

Why do they do that? Because they crave to be part of the financial power elite, and that elite knows that and bribes them with its inducements as a result.

I would expect this of Tories.

But we have to conclude that Labour has now been totally corrupted.

That is what is frightening about where we are. Morals, ethics, principles and values have left Labour. All that is left is a vacuum desperately seeking power.

When the middle class is being gutted by the economy the Tories have created we are in trouble

The Financial Fairness Foundation has a new report out this morning of which they say:

This paper outlines key findings from Caught in the middle? Insecurity and financial strain in the middle of the income distribution by Professor Donald Hirsch. Professor Hirsch’s new research considers the multiple pressures faced by people in different income bands, and particularly those in the middle of the distribution(the middle fifth of households ranked by income, adjusted for household size), that affect their ability to maintain a decent standard of living.

They note that:

They then add:

From, this they conclude:

And you now wonder why I think the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 is important with its emphasis on redistribution of income?

When the middle class is being gutted by the economy the Tories have created we are in trouble, and that is exactly what is happening.

Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth – review

In the face of soaring wealth inequality, Ingrid Robeyns‘ Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth calls for restrictions on individual fortunes. Robeyns puts forward a strong moral case for imposing wealth caps, though how to navigate the political and practical hurdles involved remains unclear, writes Stewart Lansley.

Watch a YouTube recording of an LSE event where Ingrid Robeyns spoke about the book.

Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth. Ingrid Robeyns. Allen Lane. 2023.

Ingrid Robeyns’ Limitarianism is the latest in a long line of critiques – such as Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Branko Milanovic’s Visions of Inequality – of the soaring wealth and income gaps of recent decades. Limitarianism focuses on personal wealth, which is much more unequally distributed than incomes, and is arguably the most urgent of these trends. It draws most closely on the United States, where, according to Forbes, nine of the world’s top 15 billionaires are citizens.

Ingrid Robeyns’ Limitarianism is the latest in a long line of critiques – such as Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Branko Milanovic’s Visions of Inequality – of the soaring wealth and income gaps of recent decades. Limitarianism focuses on personal wealth, which is much more unequally distributed than incomes, and is arguably the most urgent of these trends. It draws most closely on the United States, where, according to Forbes, nine of the world’s top 15 billionaires are citizens.

Robeyns argues that given the wider damage from the enrichment of the few, with its negative impact on economic strength and on wider life chances and social resilience, we must now impose a limit on individual wealth holdings. Thinkers have been making the case for this “limitarianism” and the capping of business rewards for centuries. The Classical Greek Philosopher, Plato, argued that political stability required the richest to own no more than four times that of the poorest. The Gilded Age financier, J. P. Morgan – one of the most powerful of American plutocrats of the nineteenth century – maintained that executives should earn no more than twenty times the pay of the lowest paid worker. In 1942, President Roosevelt proposed a 100 percent top tax rate, stating that “[n]o American citizen ought to have a net income, after he has paid his taxes, of more than $25,000 a year (about $1m in today’s terms).” “The most forthright and effective way of enhancing equality within the firm would be to specify the maximum range between average and maximum compensation”, wrote the influential American economist J. K. Galbraith in 1973.

The Gilded Age financier, J. P. Morgan […] maintained that executives should earn no more than twenty times the pay of the lowest paid worker.

One of the effects of the 2008 financial crisis was to trigger a debate about the role played by excessive compensation packages in banking. Others have argued that the introduction of guaranteed minimum wages – which limits employer freedom over employees – should come with a maximum too. As wealth inequality has deepened in recent decades, there have been growing calls for measures to reduce this concentration, not least among some members of the global super-rich club. Yet there has been perilously little political action. Each year the world’s mega-rich, facing few constraints, carry on appropriating a larger share of national and global wealth pools.

Robeyns sets out a powerful moral case against today’s wealth divide and asks the all-important question: “how much is too much?”. She calls for setting limits to the size of individual fortunes that would vary across countries. In the case of the Netherlands, where she lives, “we should aim to create a society in which no one has more than €10m. There shouldn’t be any decamillionaires.” This, she argues should be politically imposed. She also adds a second aspirational goal, an appeal to a new voluntary moral code applied by individuals themselves: “I contend that … the ethical limit [on wealth] will be around 1 million pounds, dollars or euros per person.”

Although there are many critics who dismiss the philosophical concept as either unfeasible or undesirable, history suggests the idea is far from utopian. Limits operated pretty effectively among nations – including the UK and the US – in the post-war decades and became an important instrument in the move towards greater equality.

War has long proved a powerful equalising force, and the post-1945 decades brought peak egalitarianism.

War has long proved a powerful equalising force, and the post-1945 decades brought peak egalitarianism. States shifted from their pre-war pro-inequality role to become agents of equality. This brought (albeit temporary) upward pressure on the lowest incomes and downward pressure on the highest. These limits operated in two ways: through regulation and taxation, and changes in cultural norms. Nations imposed highly progressive tax systems, with especially high tax rates at the top – that were sustained in the UK until the 1980s – the expansion of protective welfare states, and a shift in bargaining power from the boardroom to the workforce.

These policies were also enabled by a significant pro-equality cultural shift. This brought a tighter check on top business rewards and the size of fortunes. Until the early 1980s, business behaviour became more restrained, and wealth gaps narrowed. The kind of business appropriation that has become so widespread today would, for the most part, have been unacceptable to public and political opinion then. Gone were the public displays of extravagance and the high living of the inter-war years. Up to the 1970s, and the return of what Edward Heath called the “unacceptable face of capitalism”, executive salaries in the UK were moderated by a kind of hidden “shame gene”, an unwritten social code – similar in some ways to Robeyns’ call for voluntary limits – which acted as a check on greed. It was a code that was largely adhered to, partly because of fear of public outrage towards excessive wealth.

Up to the 1970s, and the return of what Edward Heath called the ‘unacceptable face of capitalism’, executive salaries in the UK were moderated by a kind of hidden ‘shame gene’

Robeyns is making a conceptual case. She doesn’t give much detail of how limitarianism might work in practice, and doesn’t draw lessons from the post-war experience (though this was the product of the particular circumstances of the time). She recognises the hurdles needed to make the politics of limitarianism a reality. There are plenty of questions of detail that would need to be settled. How, as a society, would we determine the appropriate “rich lines” above which is too much? Would the “undeserving rich” whose wealth is achieved by extraction that hurts wider society, be treated differently from the ‘deserving’ who through exceptional skill, effort and risk-taking, create new wealth in ways that benefit others as well as themselves?

The expectation that the tremors of the 2008 meltdown would trigger a shift towards a more progressive governing philosophy that embraced a more equal sharing of wealth has failed to materialise.

The greatest hurdle is political. The expectation that the tremors of the 2008 meltdown would trigger a shift towards a more progressive governing philosophy that embraced a more equal sharing of wealth has failed to materialise. The pro-market, anti-state politics of recent decades are now largely discredited. International Monetary Fund staff, for example, have called neoliberal politics “oversold”. There are widespread calls for the reset of capitalism, with as Robeyns puts it, “a more considerate, values-based economic system”. Although such a system may yet emerge, there are few signs of the kind of value-shift and new cultural norms that would be a pre-condition for a politics of restraint and limitarianism.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: dvlcom on Shutterstock.

Wealth Inequality by Age in the Post‑Pandemic Era

Editor’s note: Since this post was first published, percentages cited in the first paragraph have been corrected. (February 7, 1pm)

Following our post on racial and ethnic wealth gaps, here we turn to the distribution of wealth across age groups, focusing on how the picture has changed since the beginning of the pandemic. As of 2019, individuals under 40 years old held just 4.9 percent of total U.S. wealth despite comprising 37 percent of the adult population. Conversely, individuals over age 54 made up a similar share of the population and held 71.6 percent of total wealth. Since 2019, we find a slight narrowing of these wealth disparities across age groups, likely driven by expanded ownership of financial assets among younger Americans.

Data

We use the quarterly Distributional Financial Accounts published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. These data combine sectoral balance sheets from the Fed’s Financial Accounts and individual-level data from the Survey of Consumer Finances to estimate wealth holdings by wealth component and demographic group. We examine wealth dynamics from 2019:Q1 through 2023:Q3 for three age groups: 18-39, 40-54, and 55 and over. To calculate real wealth growth, we deflate age group wealth levels in each quarter by the age group-specific price indices developed in the Equitable Growth Indicators series.

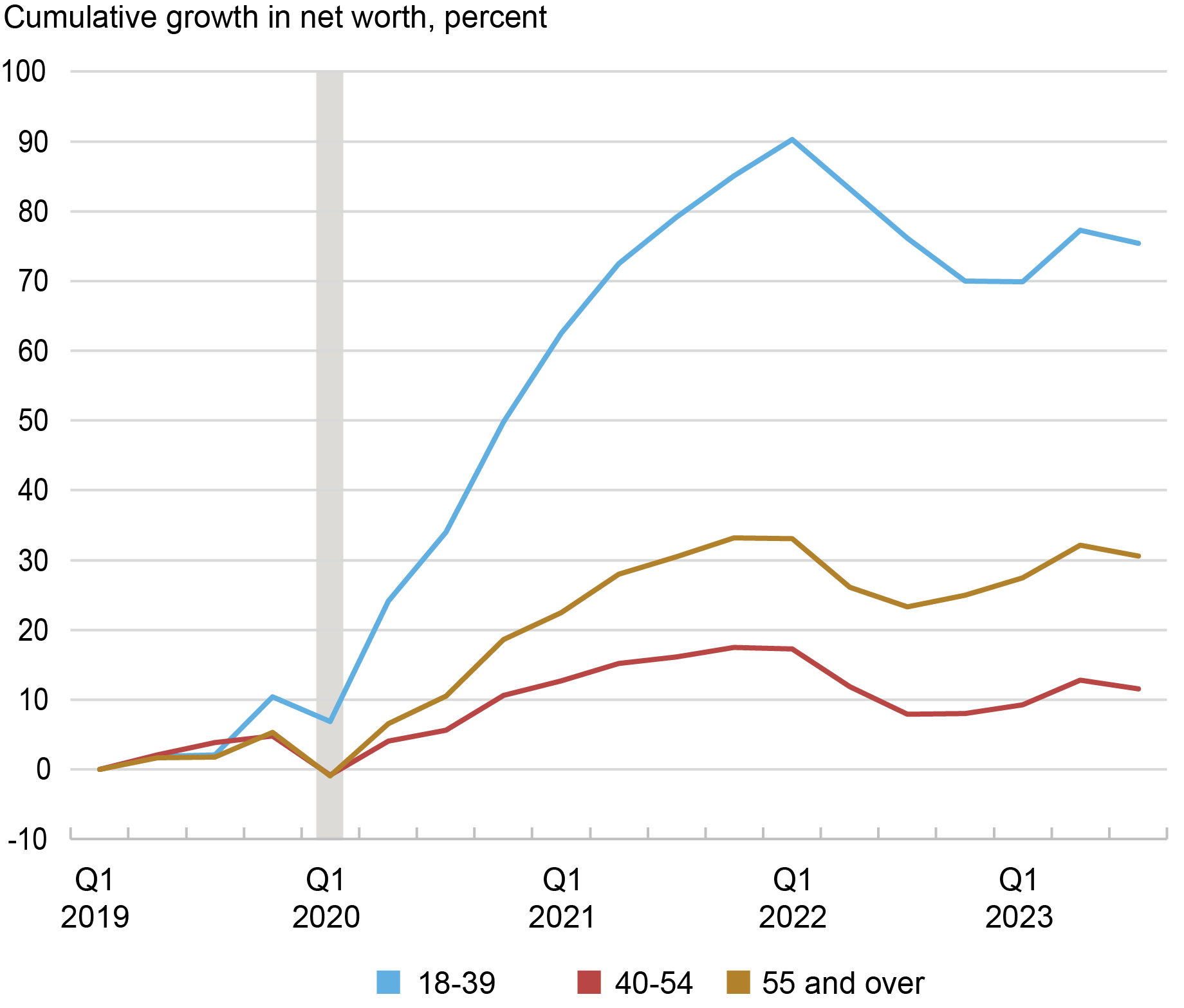

Real wealth has increased for all three age groups since 2019, but the change has been most dramatic for younger adults (see chart below). For individuals 39 and younger, wealth increased by 80 percent. In contrast, it grew by only 10 percent for those aged 40-54 and by 30 percent for those 55 and over.

Younger Adults Far Outpace Other Groups in Wealth Growth since the Pandemic

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

Note: Calculations are based on real (inflation-adjusted) prices.

What accounts for the dispersion in wealth growth over this period? There is very little dispersion in growth of liabilities. The growth rate of liabilities among 40–54-year-olds was only about 5 percentage points higher than those of the other age groups. Real estate assets, which increased by about 40 percent across groups as a result of rising home prices, contribute to but do not fully account for the dispersion in wealth growth (right panel of the chart below).

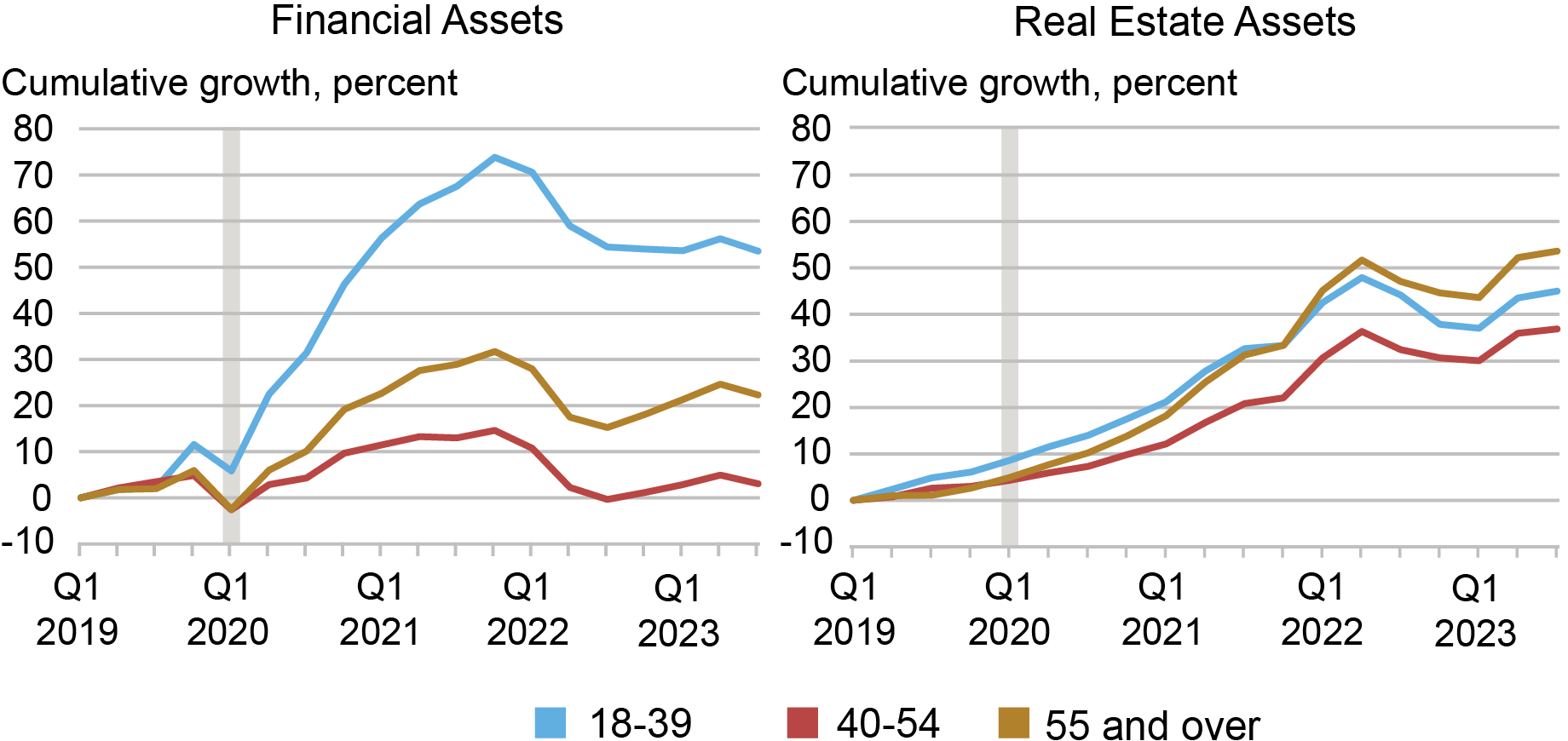

Financial assets contributed most to the differential growth in wealth over this time (left panel below). Financial asset prices rose through much of the COVID period. Those under 40 saw a greater than 50 percent increase in the real value of their financial assets between 2019 and 2023. Those who were 40-54 saw only a 3 percent increase, while those over 54 saw about a 20 percent increase.

Financial Assets Grow Most Rapidly for Younger Adults while Real Estate Growth Is Relatively Even

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

Note: Calculations are based on real (inflation-adjusted) prices.

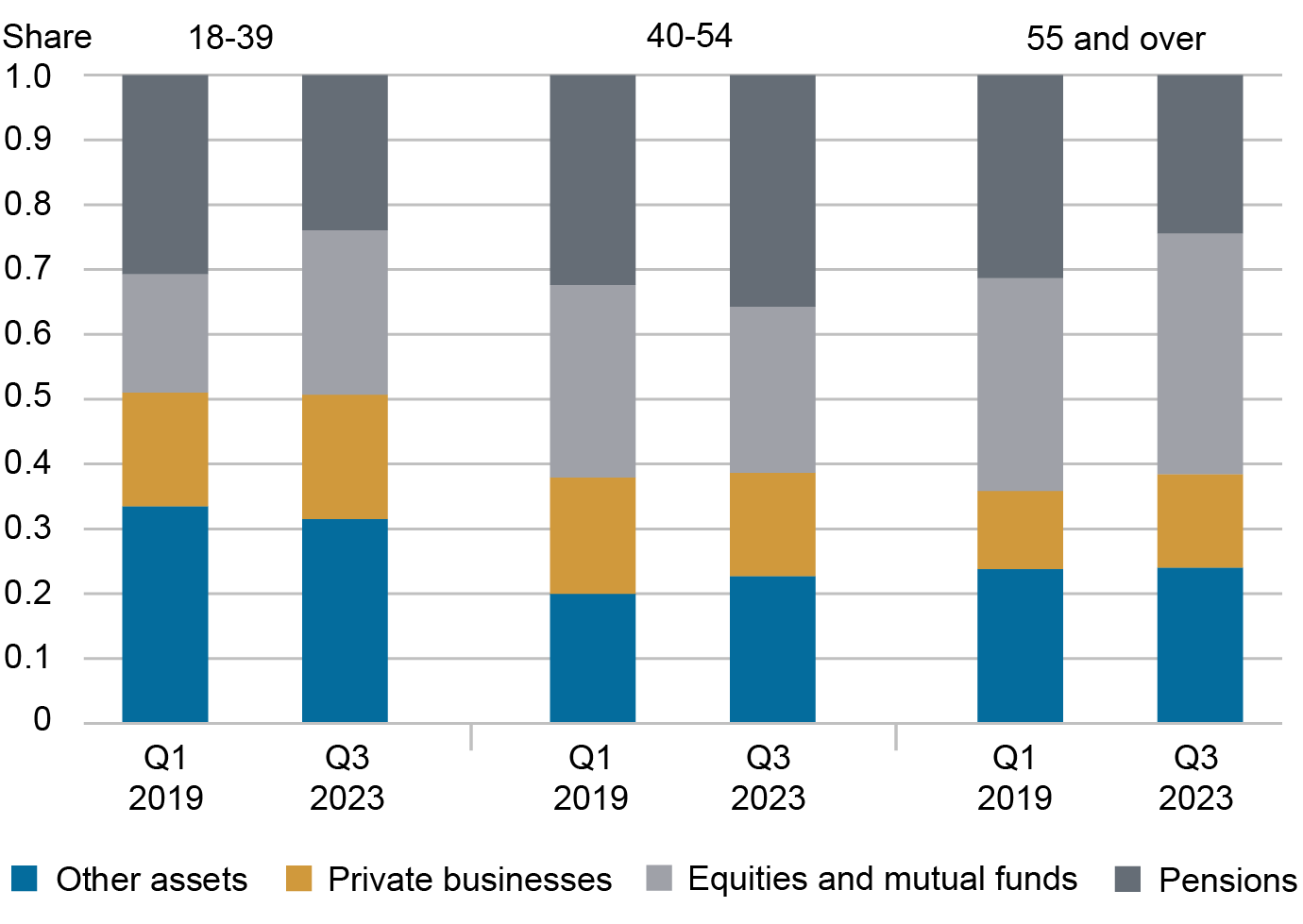

Financial Asset Composition

To understand this dispersion in wealth, we consider which financial assets each age group held. In 2019, all age groups held 31-32 percent of their financial assets as pensions (figure below). The two younger age groups held about 18 percent of their wealth in business assets, compared to 12 percent among those over 54. The larger differences are in the share held in corporate equities and mutual funds. Those under age 40 held 18 percent of their wealth in equities and funds, compared to 30 and 33 percent for the two older age groups.

Younger Adults Posted Greatest Portfolio Shift toward Equities and Mutual Funds

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; authors’ calculations.

By 2023:Q3, corporate equities and mutual funds made up 37 percent of the financial assets held by those over 55, up from 33 percent in 2019:Q1. For individuals under 40, meanwhile, this share rose to 25 percent, compared to 18 percent in 2019:Q1. Thus, the over-55 group saw their equity/mutual fund portfolio share increase by 12 percent and the under-40 group’s equity share went up by a whopping 39 percent. Accordingly, the share held in pensions shrunk for both of these age groups. In contrast, 40–55-year-olds saw their equity/mutual fund portfolio share decrease from 30 to 25 percent, with their pension holdings climbing from 32 percent to 36 percent.

The under-40 group experienced a much greater increase in equity portfolio share than the older groups did; this increased exposure to equities—the fastest-growing financial asset class during the period—enabled younger adults to record higher growth in both financial assets and overall wealth. This shift in portfolio composition toward equities likely reflects the fact that younger adults, being farther away from retirement, can afford to invest in risky assets at a higher rate than older adults. The youngest age group is also the poorest and thus received much of the COVID-era fiscal stimulus, granting them excess savings to invest in equities. (It is worth noting here that our data do not allow us to separate changes in investments from changes in returns; the results we identify are a combination of both factors.)

Conclusion

The pandemic and subsequent changes in the market have had differing effects on net worth across age groups. Analyzing shifts in the distribution of wealth since 2019, we find that faster wealth growth among younger adults has led to a limited narrowing of age-based wealth disparities over the past four years. This was largely due to changes in holdings of financial assets across the three age groups, with the under-40 group shifting toward equities at the highest rate amid rising equity prices. We will continue to monitor changes in the wealth distribution as the policy and economic environment evolves.

Chart data ![]()

Net Worth by Race and Age data ![]()

Pension data ![]()

Equities and Mutual Funds by Age data ![]()

Rajashri Chakrabarti is the head of Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Ben Lahey is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, Natalia Emanuel, and Ben Lahey, “Wealth Inequality by Age in the Post‑Pandemic Era,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/02/wealth-inequality-....

Recent Disparities in Earnings and Employment

Inflation Disparities by Race and Income Narrow

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Racial and Ethnic Wealth Inequality in the Post‑Pandemic Era

Editor’s note: The DFA data upon which this post was based show a decline in the aggregate real wealth of Black households after 2019, as reported here. The authors are currently reviewing the data to determine whether a similar pattern exists for the typical Black household. (March 1, 3:47 pm)

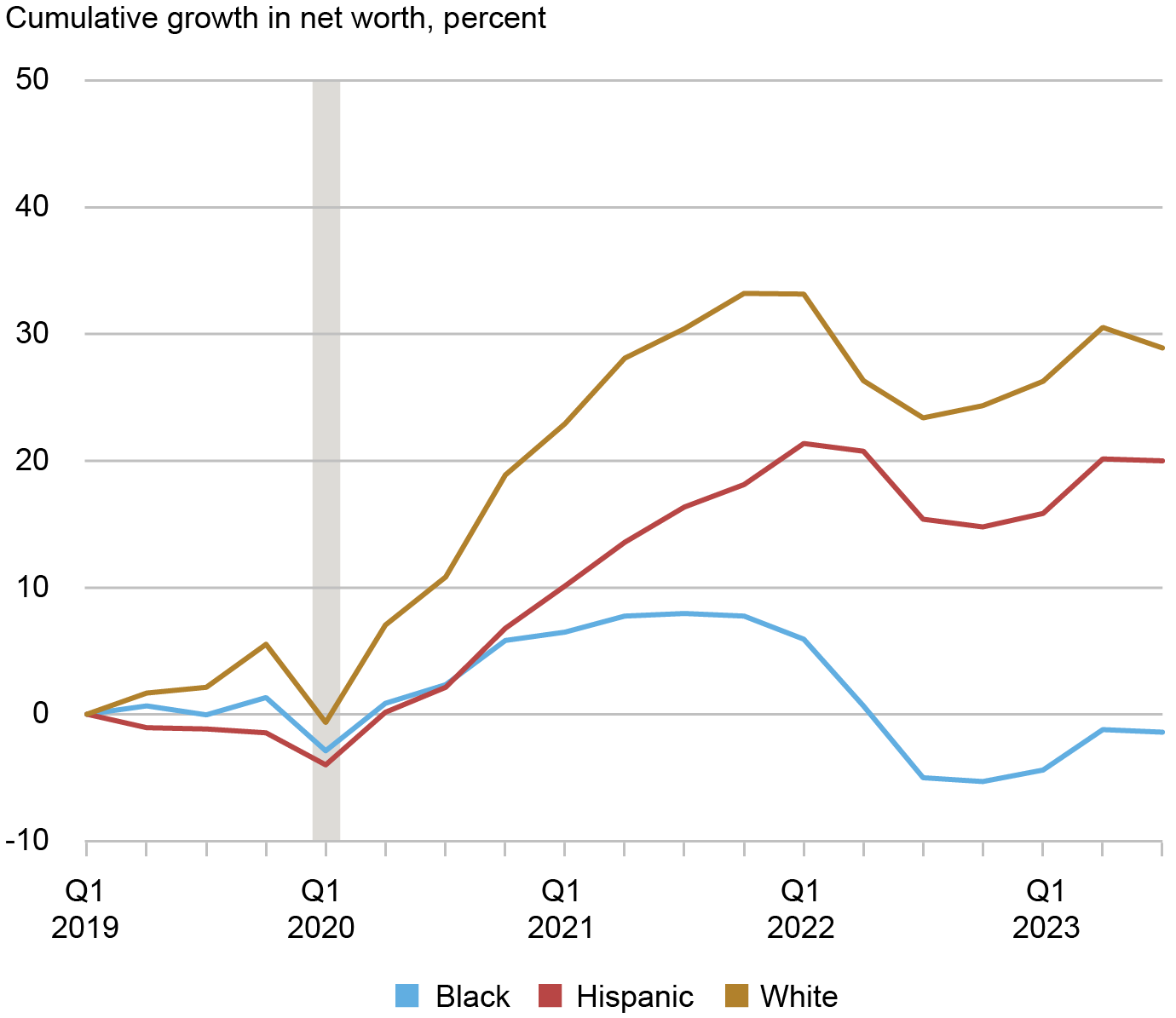

Wealth is unevenly distributed across racial and ethnic groups in the United States. In this first post in a two-part series on wealth inequality, we use the Distributional Financial Accounts (DFA) to document these disparities between Black, Hispanic, and white households from the first quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2023 for wealth and a variety of asset and liability categories. We find that these disparities have been exacerbated since the pandemic, likely due to rapid growth in the financial assets more often held by white individuals.

The quarterly demographic wealth distributions published in the DFA by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System are estimated using microdata from the Survey of Consumer Finances and aggregate financial data from the Fed’s Financial Accounts series. Sample size concerns lead us to omit Asians, Pacific Islanders, and other smaller groups from this analysis, so references hereafter to the “study population” refer to Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic white adults. We refer to non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic whites as Blacks and whites below respectively. We define wealth as net worth (assets less liabilities).

At the beginning of 2019, Hispanic and Black individuals constituted 18 percent and 13 percent of the study population, respectively, yet they held just 2.7 percent and 4.9 percent of total net worth of this population. Meanwhile, 69 percent of the population was white and held 92.4 percent of U.S. net worth.

Racial and Ethnic Wealth Inequalities Have Deepened since the Pandemic

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics, and authors’ calculations. “Net worth” is total assets less total liabilities. Note: Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and other groups are excluded for sample size concerns

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics, and authors’ calculations. “Net worth” is total assets less total liabilities. Note: Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and other groups are excluded for sample size concerns

We find that 2019-2023 growth in real net worth was greater for white individuals than for Black and Hispanic individuals. We calculate real wealth growth using the race and ethnicity specific price indices presented in the inflation inequality section of the Equitable Growth Indicators series. The chart above shows that growth in the real net worth of white individuals since 2019 outpaced growth in the real net worth of Black and Hispanic individuals. The cumulative growth by 2023:Q3 relative to 2019:Q1 for white individuals exceeded that for Black and Hispanic individuals by 30 and 9 percentage points, respectively. Real Black wealth fell below its 2019:Q1 level in 2022:Q3 and remains below its 2019 level despite some recovery.

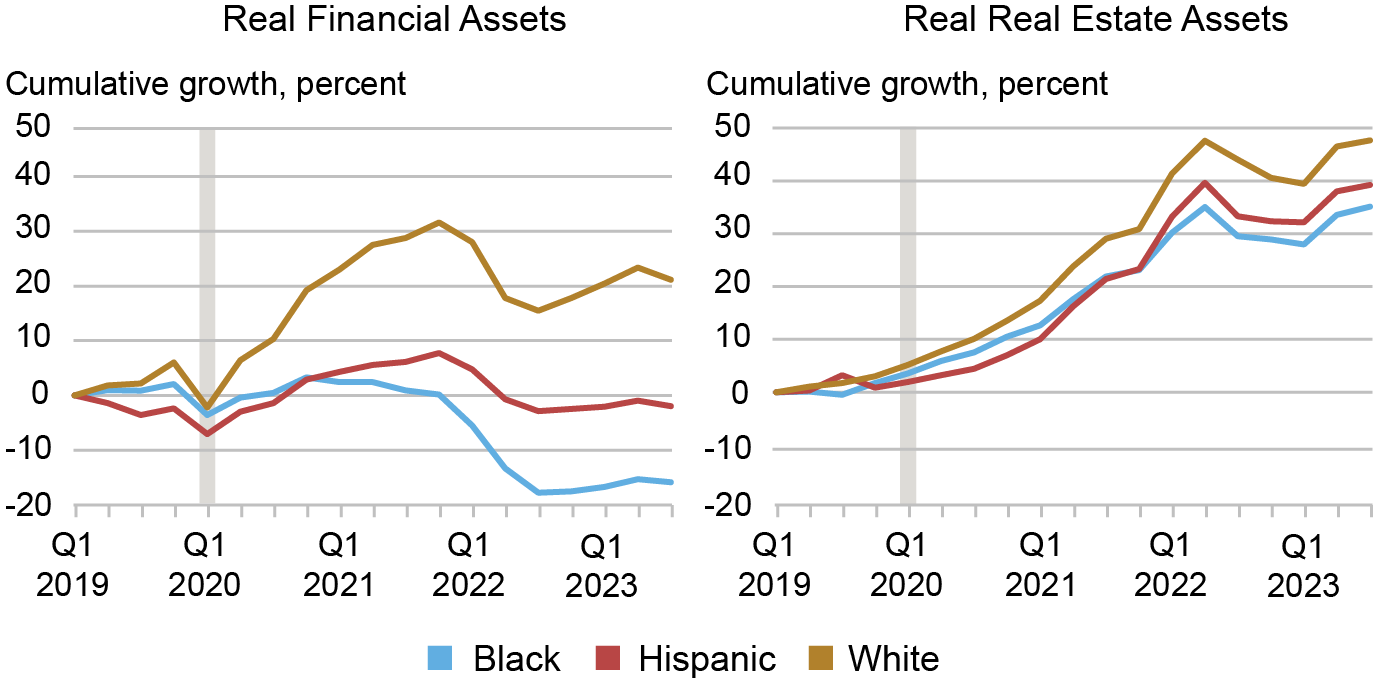

Non-White Financial Wealth Faltered While Real Estate Kept Pace

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations. Note: Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and other groups are excluded for sample size concerns.

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations. Note: Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and other groups are excluded for sample size concerns.

Next, we explore to what extent the differential growth in wealth during this period is owing to differences in the growth of its components—financial assets and real estate assets. White, Black, and Hispanic households invest their total assets in financial and real estate assets at different rates: total white assets in 2019:Q1 were about 70 percent finanical and 20 percent real estate assets, total Black assets were about 65 percent financial and 25 percent real estate, and total Hispanic assets were 50 percent financial and 40 percent real estate. We find much of the divergence in net worth by race and ethnicity since 2019 can be attributed to divergence in the real values of financial asset holdings (left panel above). It is worth noting here that our data do not allow us to separate changes in investments from changes in returns. So the results we identify here are a combination of both.

As the official sector moved to provide accommodation to combat the COVID recession, financial asset prices rose with the reopening of the economy through 2021. While financial asset prices fell notably alongside the rapid policy rate hikes in 2022, those declines did not fully offset the earlier rises. White-held real financial assets grew by 21 percent from 2019:Q1 to 2023:Q3, outpacing Black and Hispanic real finanical growth by 23 and 37 percentage points, respectively. The real value of Black-held financial assets dropped below its 2019:Q1 level after 2022:Q1 and continued to decline steadily, while the real value of Hispanic-held financial assets dipped below its 2019:Q1 level in 2022:Q2 and stagnated. Neither group’s real financial assets have recovered to their 2019:Q1 values as of 2023:Q3.

In contrast, there is minimal dispersion in the demographic growth rates of real liabilities and real real estate assets, even though white individuals experienced sharper increases in the value of real estate assets between 2023:Q3 and 2019:Q1 (right panel above). Additionally, the growth in the real net worth gap and real asset gap by race and ethnicity above are mostly contributed by growth in the gap of the corresponding nominal values rather than differences in inflationary experiences faced by these groups during this period. Below we try to understand the reasons behind the markedly sharper growth in financial assets of white individuals.

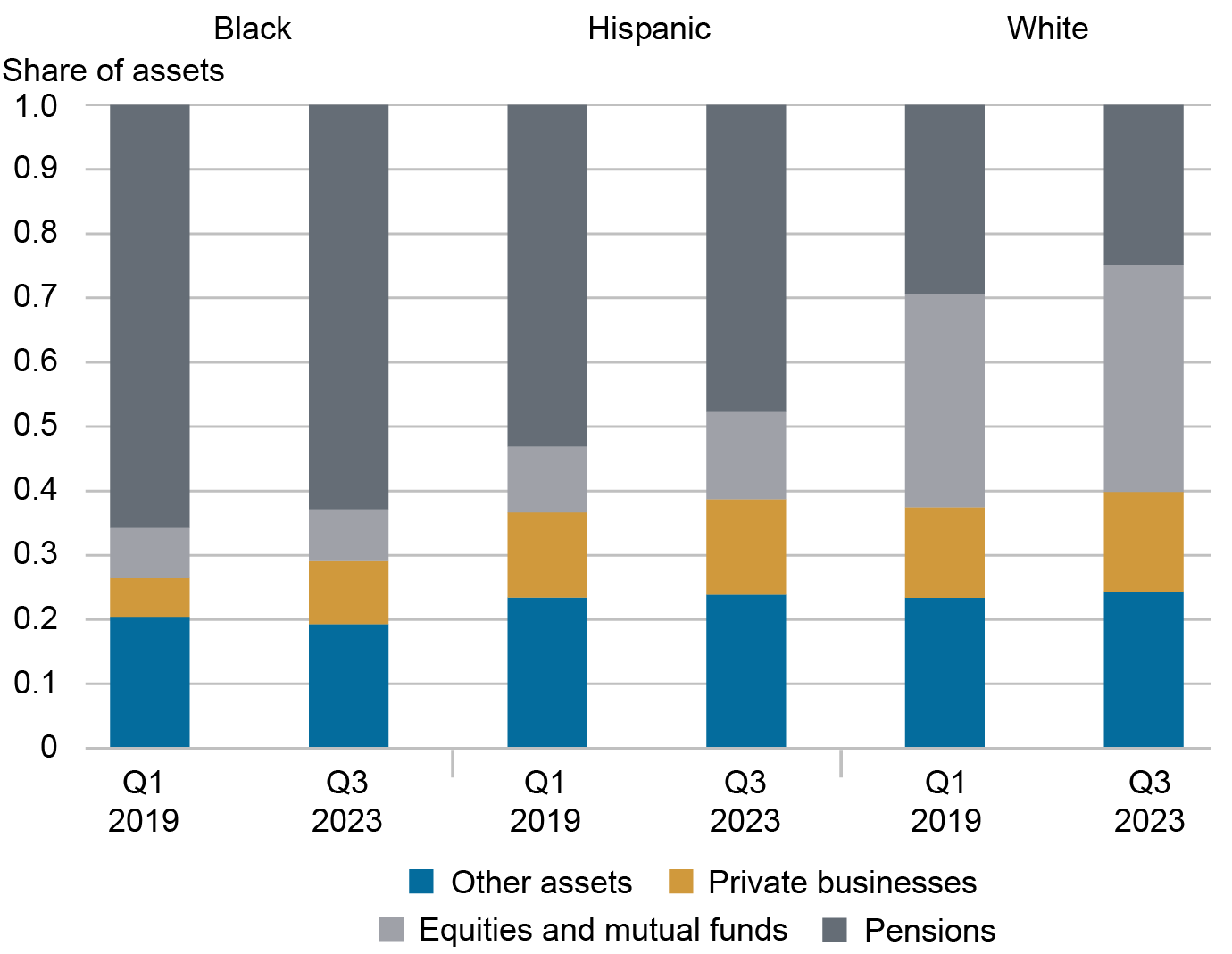

Financial Asset Porfolios Differ Starkly By Race and Ethnicity

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics, and authors’ calculations. “Net worth” is total assets less total liabilities.

Sources: Distributional Financial Accounts via Federal Reserve, Current Population Survey via IPUMS, Consumer Price Index via Haver Analytics, and authors’ calculations. “Net worth” is total assets less total liabilities.

The chart above depicts the asset classes each racial and ethnic group held in 2019:Q1 and 2023:Q3. All three groups allocate similar shares of their financial asset portfolios to “other assets”—composed of insurance payouts, mortgage assets, and other small, miscellaneous assets—but exhibit differences across the other categories. More than 50 percent of Black financial wealth is in pensions (which includes both defined benefit and defined contribution pensions) and less than 20 percent is stored in private businesses, corporate equities, and mutual funds while less than 30 percent of white finanical wealth is invested in pensions and about 50 percent is in businesses, equities, and mutual funds. Hispanic financial asset allocations are similar to those of Black individuals but with slightly more investment in businesses, equities, and mutual funds and slightly less in pensions.

The groups with more exposure to businesses, equities, and mutual funds experienced much faster financial asset growth since the first quarter of 2019 as much of the period was associated with substantive appreciation of these specific asset values. In the next post in this two-part series on wealth inequality, we present differences in wealth growth by age groups during the 2019:Q1 to 2023:Q3 period.

Chart data ![]()

Net Worth by Race and Age data ![]()

Pension data ![]()

Rajashri Chakrabarti is the head of Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Ben Lahey is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

By Rajashri Chakrabarti, Natalia Emanuel, and Ben Lahey, “Racial and Ethnic Wealth Inequality in the Post‑Pandemic Era,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/02/racial-and-ethnic-....

Wealth Inequality by Age in the Post-Pandemic Era

![]()

Economic Inequality: A Research Series

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences – review

In Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences, Dirk-Jan Koch examines the unintended effects of development efforts, covering issues such as conflicts, migration, inequality and environmental degradation. Ruerd Ruben finds the book an original and detailed analysis that can help development policymakers and practitioners to better anticipate these consequences and build adaptive programmes.

Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences. Dirk-Jan Koch. Routledge. 2023.

Dirk-Jan Koch’s Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences offers a rich discussion on the unintended consequences of development efforts, including effects on conflicts, migration and inequality and changes in commodity prices, human behaviour, institutions and environmental degradation. The book explains how different perceptions of donors and recipients lead to quite opposite strategies (eg, for managing the Haiti earthquake), whereas in other settings aid programmes can even intensify local conflicts or spur deforestation.

Dirk-Jan Koch’s Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences offers a rich discussion on the unintended consequences of development efforts, including effects on conflicts, migration and inequality and changes in commodity prices, human behaviour, institutions and environmental degradation. The book explains how different perceptions of donors and recipients lead to quite opposite strategies (eg, for managing the Haiti earthquake), whereas in other settings aid programmes can even intensify local conflicts or spur deforestation.

Koch devotes due attention to the aggregate impact of development activities through so-called backlash effects, negative spillovers and positive ripple effects.

Koch devotes due attention to the aggregate impact of development activities through so-called backlash effects, negative spillovers and positive ripple effects. Many of these effects also occur in Western countries, where they are commonly labelled as crowding-in and -out, linkages and leakages, and substitution effects. Each chapter includes real-life examples (mostly cases from sub-Saharan Africa), ranging from due diligence legislation on conflict minerals in DR Congo to the experiences of the author’s parents with the Fairtrade shop in the tiny Dutch village of Achterveld.

Koch consistently argues that the analysis of unintended effects is helpful to unravel the complexities of development cooperation and enables better identification of incentives that allow for more adaptive planning. This is a welcome contribution, since it provides a common language for better communication between development agents.

Everyone involved in development programmes is invited by this book to reflect on their own experiences with unintended consequences. I still remember the shock when an external review of a large integrated rural development programme in Southern Nicaragua revealed that most funds were spent at the local gasoline station and car repair workshop for maintenance of the project vehicles. My original enthusiasm for Fairtrade certification of coffee and cocoa cooperatives was substantially reduced when I became aware that price support enabled farmers to maintain their income with less production and therefore increased inequality within rural communities.

Koch consistently shows that it is important and possible to disentangle each of these possible or likely side effects and to act to combat them.

The systematic overview of unintended consequences of foreign aid gives an initial impression that development cooperation is a system beyond repair. This is, however, far from the truth. Koch consistently shows that it is important and possible to disentangle each of these possible or likely side effects and to act to combat them. That requires an open mind and thorough knowledge of responses by different types of agents and institutions.

The analysis falls short, however, in showing that several types of unintended consequences are likely to interact (such as price and marginalisation effects, or conflict and migration effects). Other consequences may partially overlap or perhaps compensate for each other. Moreover, there is likely to be a certain ”hierarchy” in the underlying mechanisms, where behavioural effects, governance effects and price effects crowd out several other consequences. In addition, a further analysis of the development context and the influence of norms and values might be helpful to better understand why certain effects occur, or not.

There is likely to be a certain ‘hierarchy’ in the underlying mechanisms, where behavioural effects, governance effects and price effects crowd out several other consequences

Koch argues that unintended consequences are frequently overlooked due to “linear thinking” in international development. He probably refers to the dominance of logical frameworks in traditional development planning and the recent requirement for presenting a Theory of Change with different impact pathways for development programmes. Since links and feedback loops between activities are already widely acknowledged, Koch seems to merge “linearity” with “causality”. For responsible development policies and programmes, we need better insight into the cause-effect relationship, recognising that differentiated outcomes may occur and that side effects are likely to be registered.

The absence of linear response mechanisms has been part of development thinking since its foundation by development economist and Nobel-prize winner Jan Tinbergen. His work (and my PhD thesis) heavily relied on linear programming, which is still considered as an extremely useful approach for showing that an intervention can generate multiple outcomes and that policymakers need some insights into alternative scenarios before they start to act. Impact analysis through different (quantitative and qualitative) methods digs deeper into the adaptive behaviour of development agents in response to a wide variety of incentives (ranging from financial support and legal rules to knowledge diffusion and information exchange). Our attention should be focused on understanding how non-linearity as occasioned by the involvement of multiple agents with different interests (and power) in development programmes leads to multiple – and sometimes opposing – outcomes from interventions.

Our attention should be focused on understanding how non-linearity […] in development programmes leads to multiple – and sometimes opposing – outcomes from interventions.

Koch’s analysis is based on a wide variety of case studies and testimonies, enriched with secondary research on the gender effects of microfinance, the occurrence of exchange rate disturbances (Dutch Disease), and the effectiveness of incentives to encourage natural resource conservation (Payments for Ecosystem Services). In a few cases, it makes use of more systematic impact reviews made by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) and Campbell Collaboration. Information about the size and relative importance of the unintended consequences is notably absent.

The reliance on illustrative case studies and dense description challenges the academic rigor of the book. It may hinder our understanding about the underlying causes and mechanisms behind these effects: are they generated by the development intervention themselves, or are they due to the context in which the programme is implemented, or the types of stakeholders involved in its implementation? A more comparative approach could be helpful to better understand, for instance, why microfinance was accompanied by an increase in domestic violence in certain parts of India, but not in others. Comparing different ways of designing and organising microfinance would provide clearer insights into the causes of variation in outcomes.

Opening up for such an interactive engagement with development activities asks for an institutional re-design of international development cooperation, permitting projects with a substantially longer duration (eight to ten years), closing the gap between policy and practice and accepting a political commitment for learning from mistakes. Moreover, dealing with unintended consequences requires that far more aid is channelled through embassies and local organisations that have direct insights into local possibilities and needs.

Social and community service programmes for basic education and primary healthcare tend to deliver the most tangible positive effects on incomes, nutrition, behaviour, women’s participation and income distribution.

Furthermore, focusing on adaptive planning and learning trajectories may also imply that policy priorities for foreign aid need to change. Social and community service programmes for basic education and primary healthcare tend to deliver the most tangible positive effects on incomes, nutrition, behaviour, women’s participation and income distribution. The development record of programmes for trade promotion is far more doubtful and still heavily relies on (unproven) trickle-down reasoning. Particular attention should be given to budget support and cash transfers as aid modalities with the least strings attached that show a high impact on critical poverty indicators. Contrary to these findings, several years ago the Dutch parliament stopped budget support and eliminated primary education as a key policy priority.

While the author concludes by focusing on the need to act on side effects and further professionalisation of international development programmes, more concrete leverage points could be identified. First, many of the registered effects tend to be related to cross-cutting structural differences in resources and voice, and therefore programmes that start with improving asset ownership and women’s empowerment are likely to yield simultaneous changes in different areas. Second, a stronger focus on systems analysis (beyond complexity theory) can be helpful to identify inherent conflicts and tensions in development programmes that could be the subject of political negotiation. Unravelling potential trade-offs then becomes a key component of development planning. Third, more space could have been devoted to the role of experiments in the practice of development cooperation. Policymakers expect a high level of certainty and face difficulties to become engaged in more adaptive programming. Accepting deliberate risk-taking may be helpful to improve aid effectiveness.

Policymakers expect a high level of certainty and face difficulties to become engaged in more adaptive programming. Accepting deliberate risk-taking may be helpful to improve aid effectiveness.

These reservations aside, Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences is a welcome and original contribution to the debate on development effectiveness. Koch offers a systematic conceptual and empirical analysis of ten types of unintended effects from international development activities, and its recommendations on how these effects can be tackled in practice will be useful for policymakers, practitioners and evaluators.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Jen Watson on Shutterstock.

Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Help Solve Our Problems – review

In Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Help Solve Our Problems, David Edmonds curates a selection of interviews with social science researchers covering the breadth of human life and society, from morality, bias and identity to kinship, inequality and justice. Accessible and engaging, the research discussed in the book illuminates the crucial role of social sciences in addressing contemporary societal challenges, writes Ulviyya Khalilova.

Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Help Solve Our Problems. David Edmonds. SAGE. 2023.

In the Social Science Bites podcast series, David Edmonds, a Consultant Researcher and Senior Research Associate at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, collaborated with Nigel Warburton to explore the dynamics of modern society, interviewing eminent social and behavioural scientists on different topics. The engaging discussions that resulted led Edmonds to curate a selection of the episodes in a written format to bring the research to new audiences. The resulting book, Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Solve Our Problems, offers valuable insights into various aspects of human life and society, covering subjects from morality, bias and identity to kinship, inequality and justice.

In the Social Science Bites podcast series, David Edmonds, a Consultant Researcher and Senior Research Associate at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, collaborated with Nigel Warburton to explore the dynamics of modern society, interviewing eminent social and behavioural scientists on different topics. The engaging discussions that resulted led Edmonds to curate a selection of the episodes in a written format to bring the research to new audiences. The resulting book, Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Solve Our Problems, offers valuable insights into various aspects of human life and society, covering subjects from morality, bias and identity to kinship, inequality and justice.

Understanding Humans […] offers valuable insights into various aspects of human life and society, covering subjects from morality, bias and identity to kinship, inequality and justice.

In his foreword to the book, Edmonds highlights that the selection of interviews, which translate into different chapters, reflect his own interests, though the criteria for their inclusion remains undisclosed. The book consists of eighteen chapters split between five thematic sections titled, respectively: Identity, How We Think and Learn, Human Behaviour, Making Social Change, and Explaining the Present, and Unexpected. Some topics introduced in one section can also fit into others, leading to overlaps between certain sections.

In his discussion of class, Friedman states that despite educational attainments, class privilege still significantly impacts career progression.

In the section on Identity, Sam Friedman discusses the insufficiency of education to eliminate the influence of class privilege, while Janet Carsten talks about the interconnectedness of kinship with politics, work, and gender. In his discussion of class, Friedman states that despite educational attainments, class privilege still significantly impacts career progression. The level of autonomy in the workplace, alongside one’s position and salary, could indicate whether career success correlates with social class. Friedman suggests that societal beliefs in meritocracy often overlook the inherent class-related barriers that hinder individuals’ opportunities for career development.

In the next section, Daniel Kahneman, Mahzarin Banaji, Gurminder K. Bhambra, Jonathan Haidt, Jo Boaler, and Sasika Sassen discuss various aspects of human thinking and learning. In his chapter on bias, Kahneman sheds light on biases in human thinking, discussing the dual processes of thinking: fast, associative thinking (System 1) and slower, effortful control (System 2). System 2 assists us in providing reasoning or explanations for our conclusions, essentially aiding in articulating our feelings and emotions. Education enhances System 2 and develops rational thinking, although achieving absolute rationality remains an elusive goal.

Boaler challenges the myth of innate mathematical ability, highlighting the crucial role of active engagement in developing mathematical skills.

In her chapter on the “Fear of Mathematics,” Boaler challenges the myth of innate mathematical ability, highlighting the crucial role of active engagement in developing mathematical skills. Deep thinking is crucial for developing maths skills, but it is a slow process that requires time. There is also a need for reforms in maths education, particularly addressing the issue of timed assessments that impede the brain’s capacity to develop mathematical skills effectively. Boaler states that the purpose of mathematics shouldn’t glorify speed, considering that many proficient mathematicians acknowledge working at a slower pace.

In the chapter “Before Method,” Sassen discusses how prior experiences shape research approaches, introducing the concept of “before method”, referring to both the desire for conducting research in a particular way and the actual execution of a research study. The rationale behind selecting a specific research method and topic is connected with the pre-existing experience preceding the method itself. Sassen challenges established categories by questioning whether it is possible to perceive things without initially considering categories, potentially influencing the direction of the study. She acknowledges that her awareness of prior research studies, established categories, and personal life experiences significantly shape her perception of the world as a researcher.

Following this, Stephen Reicher, Robert Shiller, David Halpern, and Valerie Curtis talk about various facets of human behaviour. Reicher discusses group dynamics, elucidating how physical proximity and psychological commonality foster different groups. Reicher also posits that group boundaries are loose and attributes this to the social changes, which, according to his explanation, result from a we-they dichotomy. Understanding intergroup interactions is crucial, particularly when individuals might not wish to be associated with confrontational aspects. However, belonging to a specific group often leads to labelling individuals, linking all their actions with that group, despite the distinctive nature of their involvement.

Halpern in his chapter on nudging explains that humans are not solely rational beings; their behaviour is influenced by various factors including impulses and emotions.

Halpern in his chapter on nudging explains that humans are not solely rational beings; their behaviour is influenced by various factors including impulses and emotions. He elaborates on how nudging proves beneficial for jobseekers, where incorporating specific human-related elements in emails encourages them to attend interviews. Halpern also posits that our inherent ‘groupish’ tendencies are intricately linked to human psychology. Various factors influence our proximity or distance from others, ultimately affecting societal progress, including economic development. Trust, for instance, varies significantly among different social classes. An individual from an impoverished social class facing financial challenges tends to have lower social trust. Conversely, someone from an affluent background might experience the opposite due to their social circle being influenced by their wealth.

Chenoweth’s research highlights the efficacy of nonviolent political action when contrasted with violent approaches, emphasising its higher success rates and potential to facilitate democratic transitions.

In the section on “Making Social Change” Jennifer Richeson, Erica Chenoweth, and Alison Liebling discuss how employing various approaches and research methods can drive social changes. Chenoweth’s research highlights the efficacy of nonviolent political action when contrasted with violent approaches, emphasising its higher success rates and potential to facilitate democratic transitions. Within the political sphere, an emerging trend is the digital revolution, distinct in some aspects from other revolutions. Erica Chenoweth also states that the digital revolution might foster a misleading impression by mobilising thousands to march in the streets.

In the section “Explaining the Present and the Unexpected,” Hetan Shah discusses the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on social and economic spheres, while Bruce Hood talks about supernatural attitudes or beliefs. Shah elucidates how the pandemic has shifted societal norms and behaviour. He also draws attention to the impact of these norms on human behaviour and the potential for fostering a fair society. Examining the pandemic from multiple angles – medical, social, and economic – deepens our understanding of human behaviour Shah emphasises that social sciences play a crucial role in unveiling how biases shape our thoughts and actions, addressing the social problems.

[Understanding Humans] provides readers with a compelling overview of exceptional research studies on how we think and act as individuals, and the social, economic, educational and political structures that we operate within.

Overall, the eclectic chapters in ‘Understanding Humans: How Social Science Can Solve Our Problems’ illuminate the profound role of social sciences in exploring and addressing social issues. This book serves as a valuable resource for a broad audience, being accessible and engaging for readers without prior knowledge or expertise in the fields drawn upon by the researchers. It provides readers with a compelling overview of exceptional research studies on how we think and act as individuals, and the social, economic, educational and political structures that we operate within.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: tadamichi on Shutterstock.