Economics

Which Keynesianism?

I posted this enormous torrent of blather on Blackboard the other day. It's mostly a restatement of stuff I've said before, but I'll repost it here for the purposes of copying and pasting in the likely case I have to restate it yet again elsewhere.

Because I've been studying economics for the last few years, rather than sticking to the curriculum and dutifully cultivating my employability, I feel obliged to chip in with a cautionary note: Almost all of the academic economists, and their policy prescriptions, which are characterised as Keynesian have nothing to do with the work of Keynes.

The post-war economic order established at Bretton Woods is conventionally understood as being Keynesian, but in fact Keynes was railroaded by the US representative Harry Dexter White, who insisted upon the system of fixed exchange rates pegged to the US dollar, with global dependency on holding US dollar reserves being greatly to America's benefit; the US gained the benefit of cheap foreign imports sold to acquire those reserves. Neither was Keynes responsible for the "Bretton Woods institutions", the World Bank and the IMF. His plan for regulating and settling international financial flows was considerably more humane than the usurious loans and standover tactics these institutions became notorious for.

Even "progressive" and "liberal" economists like Paul Krugman and Joe Stiglitz are members of the school of "New Keynesianism", a product of what Paul Samuelson called the "Neoclassical Synthesis"; taking some of the superficial trappings of Keynes' work and melding it with the earlier "neoclassical" school of economics, which Keynes actually intended to entirely overturn. Neoclassical models of the economy ignore the role of money and banking, believing that all economic transactions are ultimately barter transactions, and that money is therefore said to be "neutral", and banking is just redistribution of loanable funds, ultimately of no macroeconomic effect. Keynes wrote of this "Real-Exchange economics" (in an article unfortunately unavailable via SCU):

Now the conditions required for the "neutrality" of money, in the sense in which it is assumed in […] Marshall's Principles of Economics, are, I suspect, precisely the same as those which will insure that crises do not occur. If this is true, the Real-Exchange Economics, on which most of us have been brought up and with the conclusions of which our minds are deeply impregnated, […] is a singularly blunt weapon for dealing with the problem of Booms and Depressions. For it has assumed away the very matter under investigation.

This is the answer to Queen Elizabeth's question on how economists failed to see the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) coming; if the financial sector is macroeconomically neutral, as the neoclassicals claim, there cannot be any financial crises. However, outside the neoclassical tradition, the normal functioning of the economy, and the pathologies leading to crises, are well understood:

- The Chartalists determined that all money is credit, ultimately issued by the state. Michael Hudson recently did some exhaustive historical work on this, which David Graeber popularised in his book Debt: the First 500 Years.

- Wynne Godley showed how currency-issuing states must spend more than they tax if the private sector is to have the money necessary to spend and save.

- Irving Fisher identified the role of debt deflation in turning a rush to liquidate debt into an ongoing crisis where outstanding debts become impossible to repay.

- Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis extended Fisher's work to describe how financial crises arise from the normal workings of a capitalist economy.

- Keynes implicitly regarded the money economy as a tool for allocating real resources in pursuit of public policy objectives, a principle explicitly formulated by Abba Lerner as "functional finance". This is in opposition to the neoclassical intuition that a household is like an individual, a firm is like a household, and a government is like a firm; therefore a government must follow the principles of "sound finance" and "live within its means".

- All of the above are incorporated in the teachings of "Post-Keynesian" economics, which Keynes' biographer Robert Skidelsky considers closest to Keynes' own thinking. The sub-field of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) synthesises all of these into a single coherent framework for analysing the economies of countries which issue their own currency.

By the end of World War II, functional finance was so well established as to be almost universally understood to be common sense. The 1945 White Paper on Full Employment in Australia, prepared for John Curtin by H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, and based on the principles in Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, declared:

It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

(Emphasis mine.) As expressed by MMT, currency-issuing governments are not fiscally constrained. The only limits on public policy are real resource limits. During the last UK election campaign, Theresa May was vehemently insisting "there is no magic money tree". But in fact there is: it's called the Bank of England (we have the Reserve Bank of Australia), and Her Majesty's Treasury has an unlimited line of credit there. Whenever the government wants to spend, the Bank of England just credits the accounts of commercial banks. I was delighted when while campaigning May was confronted by a furious protester wanting to know "Where's the magic doctor tree? Where's the magic teacher tree?" The policy limits we should be worried about are real resources (including people), not money.

Nevertheless, mainstream economists and politicians believe, in some vague way, that (as Stephanie Kelton puts it) "money grows on rich people". So it's not surprising to read already on the discussion boards here that Keynesianism is all very desirable, but how will the federal government pay for it? This is a meaningless question. The government will pay for it like it pays for anything: by spending the money into existence. That's where all money comes from, net of private sector credit creation. Logically, it can't come from anywhere else. If the government were to try to achieve fiscal (or, conflating governments and firms again, "budget") surpluses over the long term by taxing more than they spend, as neoclassicals, including New Keynesians, recommend, they would merely be draining savings from the private sector for no good reason. State-issued money is an IOU, a tax credit. When the credit is redeemed it ceases to exist. The government doesn't have to tax in order to spend. It has to spend in order to tax. Think about it: where else would the first dollar ever taxed come from?

Now you might be thinking, hang on: what about the most fiscally responsible government we've ever had (Howard/Costello) and their record run of "budget" surpluses? The economy was going gangbusters! Okay, here's the fiscal balance for that period:

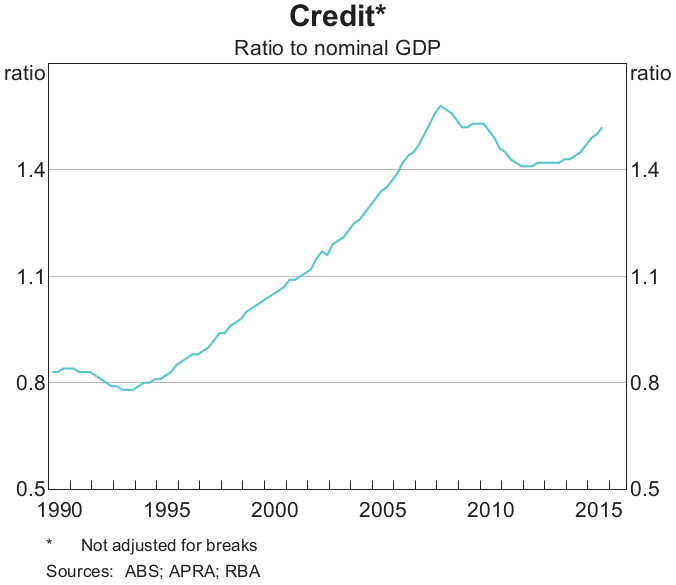

As with every currency-issuing sovereign state in history, deficits are the rule, not the exception. Here's what happened to private sector debt over the same period:

(Data from the Bank of International Settlements and OECD.) As soon as the government started taxing more than it spent, private sector debt took off, and subsequent fiscal deficits were insufficient to reverse the damage. Notably, at the same time household debt overtook corporate debt, as credit was used to sustain consumer demand, not to mention standards of living, rather than for investment in productive capacity. Australia "Nimbled it, and moved on", and to hell with the consequences.

Australia recently passed two milestones of note: total private sector debt (the blue line above) exceeded 200% of GDP — at roughly the level that Japan's private debt was at in the early 90s when its real estate bubble burst — and bank equity in residential real estate passed 50%. That's 50% of the total residential real estate stock, not just houses built in the last x years. Minsky describes the path to financial collapse as progressing through the stages of "hedge finance", then "speculative finance", and finally "Ponzi finance". When you see phenomena like interest-only mortgages — where the principal is never repaid, on the assumption that housing prices only ever go up, and the debt will be settled whenever you sell the property, presumably pocketing a tidy and lightly-taxed capital gain at the same time — you know which stage you're in.

So why does nobody in mainstream politics or economics know anything about this? To put it succinctly, because neoliberalism. On the left, the "balancing the books" rhetoric serves a useful purpose: it gives you a disingenuous pretext to do what you want to do anyway that is compatible with the dominant paradigm. As Randy Wray said at a recent MMT conference:

"[Progressives] link the good policies they want to 'we'll tax the rich to pay for it'. So when you point out we don't need to tax the rich to pay for it, they're just crestfallen because they want to tax the rich. So I say 'Of course we should tax the rich. Why? They're too rich.' You don't need any other argument than that."

Taxes drive demand for the currency. If you know you have to pay taxes, you will work to get the money to pay for it. It's a coercive way for the government to mobilise labour to achieve its policy objectives, but assuming policy is arrived at democratically, it's relatively fair and vastly preferable to the autocratic alternative of having a gun put to your head. Taxes are also a fiscal instrument that can be used to discourage certain kinds of behaviour, and harmful social phenomena (like income inequality).

In the neoliberal era, that's why Australia has a retrospective tax on education called HECS-HELP, which in turn is why SCU has no school of history, or philosophy, or in fact any of the traditional academic disciplines. Students know that their education will be retrospectively taxed, so they can't afford to choose disciplines unlikely to offset that tax with increased earnings. There are twice as many universities as there were in 1988, but the new ones are glorified vocational colleges with next to no permanent academic staff. Australian post-Keynesian economist Steve Keen, who correctly predicted — and more importantly, explained — the GFC, subsequently lost his job at the University of Western Sydney when they closed down their economics department. Who needs academic economics when you have business studies courses, after all? He ended up at Kingston University in London, another young neoliberal institution, where last year he was given an ultimatum to spend more hours teaching or take a significant pay cut. He's ended up having to put his hat out for donations from the public in order to continue his work as a public intellectual.

Why would public policy function like this? Why would policy makers want a population uneducated about how the world actually works, and instead merely trained in how to work in it? Why is the conventional wisdom so full of assertions that are demonstrably untrue, and profoundly damaging to society? Paul Samuelson, author of the macroeconomics textbook that gave generations of undergraduates a completely misleading interpretation of Keynes' work explained this in an interview:

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] in every short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say "uh, oh what you have done" and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I see merit in that view.

So basically, belief in myths must be maintained among the general population wherever doing so provides support for the elite political preference for small government, i.e. for control over the economy to be exercised by private finance rather than public fiscal policy. This is what neoliberalism fundamentally is, an Orwellian fiction imposed on a deliberately dumbed-down populous, with access to the truth as much the reserve of a select educated elite as ever. "Long-run civilised life" has been restored, thanks to neoliberalism's making of the 21st century by its un-making of the 20th.

I could go on forever (evidently) but others explain all this better than I:

- Here's a short interview with Steve Keen explaining how neoliberal austerity economics leads inevitably to financial crises.

- Stephanie Kelton is probably the best person to explain MMT to a general audience. Watch her describe the Angry Birds Approach to Understanding Deficits in the Modern Economy.

- Here's Bill Mitchell explaining in 15 minutes how fiscal policy works in the real world.

- Warren Mosler explains here why fiscal deficits are generally desirable. If you find reading easier than listening, I recommend Warren's slim volume (and even slimmer PDF file) Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy.

If you have read this far, I admire your tenacity.

Strange bedfellows

Via MacroBusiness, here's the TL;DR of the Business Council of Australia's submission to a 2012 Senate inquiry into social security allowances:

- "The rate of the Newstart Allowance for jobseekers no longer meets a reasonable community standard of adequacy and may now be so low as to represent a barrier to employment.

- "Reforming Newstart should be part of a more comprehensive review to ensure that the interaction between Australia’s welfare and taxation systems provides incentives for people to participate where they can in the workforce, while ensuring that income support is adequate and targeted to those in greatest need.

- "As well as improving the adequacy of Newstart payments, employment assistance programs must also be reformed to support the successful transition to work of the most disadvantaged jobseekers."

Not only did the BCA's confederacy of Scrooges suffer unaccustomed pangs of sympathy, the Liberal Party senator chairing the inquiry also agreed that Newstart is excessively miserly. However, he failed to recommend raising the allowance, saying:

"There is no doubt the evidence we received was compelling. Nobody want's [sic] to see a circumstance in which a family isn't able to feed its children, no one wants to see that in Australia. But we can't fund these things by running up debt."

Sigh. (Here we go…) There is no need to "fund these things", whether it be by "running up debt" or any other means. The Federal Government creates money when it spends. We, as a country, run out of the capacity to feed our children when we run out of food. We cannot run out of dollars, since we can create the dollars without limit.

The government does however, at the moment, have a purely voluntary policy of matching, dollar-for-dollar, all spending with government bond sales. There's no good reason for this; as Bill Mitchell says, it's just corporate welfare. Even so, selling bonds is not issuing new debt. Bonds are purchased with RBA credits (or "reserves", if you prefer). The purchasing institution simply swaps a non-interest-bearing asset (reserves) at the RBA for an interest-bearing one (bonds), still at the RBA. It's just like transferring some money from a savings account to a higher-interest term deposit account at a commercial bank; do we say that this is a lending operation? Of course not.

There is no fiscal reason why the government should punish the unemployed to the extent that they become an unemployable underclass. Even if we are generous and assume the good senator and his colleagues on the inquiry are just ignorant about how the economy works, we are still bound to conclude that there must be some (not so ignorant) people in government, who do want to see people suffering for no just reason.

Mid-life crisis – are student loan repayments really progressive?

The crack-wonk-team at London Economics have crunched the numbers on how much graduates in different professions can expect to repay in student loan costs over the course of their careers.

The post Mid-life crisis – are student loan repayments really progressive? appeared first on Wonkhe.

LEO shows how graduate pay has been squeezed

LEO data shows that, when adjusted for inflation, graduates' pay packets are being significantly squeezed. Jonathan Boys has broken down the data.

The post LEO shows how graduate pay has been squeezed appeared first on Wonkhe.

Why is there such a large gender pay gap for graduates?

Women graduates earn less than their male counterparts immediately after leaving university and in the vast majority of subjects. We pick this apart and suggest what role universities might have to play in fixing it.

The post Why is there such a large gender pay gap for graduates? appeared first on Wonkhe.

A beginner’s guide to Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data

Longitudinal Education Outcomes data could be the biggest public information shake-up for universities yet. David Morris runs through the background to LEO, its many caveats, it's ideological trajectory, and the possible policy implications.

The post A beginner’s guide to Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data appeared first on Wonkhe.

Brexit Buffet

I don't get politics. I understand particular political issues, but I never understand the state of popular opinion about them. Politics, in that sense, is that thing I'm perpetually out of step with. So I should have known that the UK leaving the European Union, appearing to me such a self-evidently bad idea, was inevitable. I am further surprised to find that on the wisdom of "Brexit" some really super-smart people disagree with me. This almost never happens; coincidence of opinion is my infallible yardstick for intelligence, after all.

I understand the main criticisms of the EU, and they bear repeating:

- The Maastricht fiscal rules (national debt must stay below 60% of GDP and annual deficits below 3% of GDP) guarantee that any country under that regime which happens not to have a large export-driven economy (like for instance Germany) will be unable to use fiscal deficits to offset current account deficits and maintain spending power in the private sector (see Godley's sectoral balances for how that works), and will be driven into a debt deflation spiral that shrinks their economy. That is, the more the Eurozone periphery nations try to stick to the rules and end up liquidating productive capacity in the attempt to reduce debt/deficits, the less able they become to stick to the rules, and the worse they suffer. When Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Greece joined the EU, they also joined the third world. Any other outcome was a logical impossibility.

- The Euro is the most disastrous faux-gold-standard since the last one. If you ever need an argument against independent central banks, just point to the way the ECB, the most independent central bank in history - 100% free of democratic accountability, has turned Europe into a game of beggar-thy-neighbour mercantilism. Unnecessary suffering on a grand scale, for no reason other than the ridiculous pursuit of larger numbers on the ECB's computer. Not even any useless lumps of soft yellow metal to show for it! Under the Euro, a country's economic prospects end up not being a function of their real productive capacity, but a result of a surfeit of or lack of those magic numbers.

So I understand why Bill Mitchell would welcome the Leave vote as the return of the class struggle, and why Steve Keen and Mark Blythe also see leaving as the most sensible course of action for any country able to do so. I have two reasons to disagree:

1. The quickest and easiest solution for any individual EU member state able to leave is not the best long-term solution for Europe.

Thanks to the City of London, the UK has the economic heft to wear any negative consequences of Brexit (although this is rather like sailing into a storm and thinking "It's a good thing we have that huge, unexploded bomb to use as ballast!"). Countries currently under the thumb of the "troika" of the ECB, the IMF, and the Eurogroup do not have a realistic, or at least tolerably painless, exit option, and it is in nobody's interest that they should continue to suffer. It may be satisfying to say "Congratularions Dr. Schauble, your prize is the 1930s," but it would have been better to deploy the UK's weight towards building a democratised EU, rather than a disintegrating Europe.

2. There is no reason to believe the scope for meaningful democracy in the UK will be improved by Brexit.

I will be dancing in the street when Jeremy Corbyn's Labour wins the 2020 (or earlier, maybe) general election. But it will be more for what it says about the UK's political aspirations than in anticipation of of what Labour will be able to achieve. John McDonnell has already undertaken to follow monetarist "balanced budget", "sound finance" policies, rather than the "functional finance" which is necessary to defuse the City of London financial bomb and rebuild the real economy. Regardless of which party is in power, for the forseeable future the UK has merely shed the straightjacket of Maastricht for the straitjacket of the Charter for Budget Responsibility. In the process the far right has come to feel vindicated and emboldened.

I would love to be wrong about this, but I fear I am merely in the minority, as usual.

The Joy of Economic Irresponsibility: or how I learned to stop worrying and love the public debt

If there's one thing I've learned in the last year that I think is so important it's worth shouting from the rooftops, it's that simultaneously studying economics and the psychology of stress while also being personally stressed about money is a very, very bad idea.

If there are two important things I've learned in the last year, I'd say that the more generally applicable one to the citizen in the street is that a government which issues it's own money can never run out of it.

Such a government can of course pretend, or at least behave like, it can run out of money. In fact, many have done so for the last thirty years or so, and the results have been disastrous. You don't have to take my word for it. Here are some graphs, mostly from the RBA Chart Pack, except where otherwise indicated. Here's the Australian government fiscal balance, misleadingly labelled "budget balance" as per the conventional misunderstanding of reality.

Things took a dip from 2007/8, but deficits are improving, and we were in surplus for most of the preceeding decade. And that's good, isn't it? Surpluses mean we have more money, don't they?

Generally, yes. A "budget surplus" for a business or household means more money at hand to spend later. However, for an economy with a sovereign-currency-issuing government, public fiscal surpluses mean we have less money.

How is this possible? To understand this, you have to understand that accountancy—specifically double-entry bookkeeping and balance sheets—is the foundation of economics; at least economics of a realistic kind. All money is credit money. You make money—literally—by being in debt to somebody, and by denominating this debt in the country's transferrable unit of account. Spending is the simultaneous creation of a debt on the buyer's side of the ledger, and a corresponding credit on the seller's side. However, if you happen to hold enough credits that have already been generated as the flipside of a debt in your favour, you can use these credits to immediately cancel the debt of the current transaction. One way most of us do this on a daily basis is by using cash. Cash is a transferrable token of public sector debt and private sector credit.

Three percent of the immediately-spendable money in the private sector is in the form of cash. The other 97% is just numbers stored on computers in the commercial banking sector. Most of this is money that originated as commercial bank loans, and will disappear from the bank's balance sheets as those loans are repaid (though of course in the meantime more loans will have been made). However, a significant amount of money originates as loans the government makes to itself (technically the central bank lends to the treasury), eventually ending up in the private sector as cash, or (through a mindbending process I will mercifully omit from this account) as commercial bank deposits. A currency-issuing government can always lend more money to itself in order to spend, and never has to pay it back. It follows that such a government does not need to tax in order to spend, and only ever taxes for other reasons. Economics textbooks, and economic commentators, routinely get this utterly and comprehensively wrong. Consider this textbook description of economic "automatic stabilisers":

"During recessions, tax revenues fall and welfare payments increase thereby creating a budget deficit. In times of economic boom, tax revenues rise and welfare payments fall creating a budget surplus."

Budget deficits are not an eventual consequence of government spending; the spending and the creation of a debt are the same operation. Tax revenues merely redeem a part of the already-accrued debt; the money issued by public spending is a public IOU that effectively disappears when private parties use it settle their tax debt owed to the public. Tax revenues therefore cannot be used to fund public spending; in order to spend, new public debt must be issued. The automatic stabilisers are real (assuming a somewhat sensible tax system), but the important part of their function is on the private side: injecting new money to stimulate demand when needed, or putting the brakes on dangerous speculative activity in a boom. The government's fiscal position from one year to the next is an inconsequential side-effect.

Taxation is the elimination of money, and hence of the demand for goods, services, and assets that drives the private sector economy. Don't believe me? Lets take a wider focus on the fiscal balance numbers above:

[Source]

Generally, and especially prior to the neoliberal period, public fiscal surpluses are the exception, not the rule. And for a good reason; it's generally not a good idea to drain demand out of the economy. So what happens when you toss good sense aside, and insist on surpluses for their own sake? Here's what happened to public sector debt:

I'm presuming (the ABS Chart Pack doesn't specify) that this is debt owed to private sector banks in the form of loans and government securities. I should stress that, as with taxation, these operations are not required to finance spending, and are only ever done for other reasons (such as hitting interest rate targets). Also, because they don't issue currency themselves (though this is possible, and has worked elsewhere), lower levels of government do have to rely in part on revenue-raising to fund spending, though grants from the federal government also play a big part in determining their fiscal position.

Still—phew!—we got that scary public sector debt under control until the GFC, and we can do it again! But hang on, if that's taking money out of the private sector, where does the private sector get the money to sustain demand? Here's the private sector debt over the same period:

Note that this is one and a half times GDP, compared to the one third of GDP outstanding to the public sector, at the height of its alleged fiscal irresponsibility. When government self-imposes limits on its ability to spend, private sector credit creation takes up the slack. Who do you want controlling how much money is created, who gets it, and what it gets spent on? A mix of the commercial finance sector and a (somewhat) democratically-accountable government? Or just the bankers?

Most of private-sector money creation is commercial bank loans, and as economist Michael Hudson notes, in the US, UK, and Australia, 70 percent of bank loans are mortgages. That's a hell of a lot of money (what's 70 percent of one and a half times GDP?) dependant for its existence on the soundness of pricing for a single class of asset. If real estate prices suddenly crash, and mortgagees start to default on their loans, poof! The corresponding credits on the other side of the ledger are gone too, and the real estate sector takes the whole economy down with it. You can't argue with balance sheets.

Still, I expect we'll be fine as long as we stay the fiscal responsibility course, and don't let the government "spend more than it earns". Real estate prices only ever go up, don't they? And it's not like bankers would ever be led by their own short-term interests to make a huge amount of risky loans and inflate an enormous real estate price bubble…

Saturday, 16 April 2016 - 8:30pm

"Expansionary fiscal policy is taboo, because it threatens to increase national debt further. But much depends on how governments present their accounts. In 2014, the Bank of England held 24% of UK government debt. If we discount this, the UK’s debt/GDP ratio was 63%, not 92%.

"So it makes more sense to focus on debt net of government borrowing from the central bank. Governments should be ready to say that they have no intention of repaying the debt they owe their own bank. Monetary financing of government spending is one of those taboo ideas that is sure to gain support, if, as is likely, economic recovery grinds to a halt."

Thank you, thank you, thank you, Professor Lord Skidelsky! I disagree with much of the preamble (including the implication that Shakespeare intended Polonius' stream of adages to be taken seriously; I fancy Shakespeare's audiences would find being neither a borrower nor a lender—particularly the former—as ludicrously impractical as would today's precariat), but I love the conclusion.

Private mortgage debt is bad. Private credit card or loan shark debt (the categories are not exclusive) is very, very bad. Money the government owes itself is at worst a misleading artifact of an accounting convention, at best an indirect metric of public economic stimulus. It harms nobody but those loan sharks and assorted greater and lesser parasites who currently benefit from the neoliberal debtfare system; that's the only reason it's a taboo.

Wednesday, 24 February 2016 - 6:57pm

At the Campaign for America's Future, Dave Johnson has a comprehensive roundup of the Sanders “Economic Plan” Controversy. The controversy is practically non-existant outside of the left wing of the Republican Party, i.e. the Clinton/Obama/Clinton Democrats. The plan is pretty much what you'd expect from a New Dealer, as Chomsky characterises Sanders. It's a welcome change from policies that have created the post-GFC malaise, but hardly radical or historically unprecedented.

As you'd expect, economists with intelligence and integrity like Bill Black and Jamie Galbraith did their best to introduce some reason to public discourse, while journalists on the economics beat largely ignored tham and scrambled to stake out a position that they could defend as balanced. As you'd also expect, but nonetheless disappointingly, Paul Krugman lined up with those he would usually deride as Very Serious People (VSPs). I generally enjoy Krugman. He's witty and articulate, and performs a useful service against Republican politicians beloved of VSPs such as Ron Paul, Paul Ryan, Rand Paul, and Ryan Rand. (Hang on; I think one of those isn't a real person. Maybe more than one.)

Sadly, Krugman is not inclined to entertain ideas outside the range of opinions between Clinton and Bush, or if you prefer, Clinton and Bush (or Bush). And those issues upon which "moderate" Republicans and Democrats agree do not for Krugman count as contestable issues; they are part of the built-in political furniture. In this sense, he's as much a VSP as anybody. If he wasn't, he wouldn't be doing his job.

The New York Times' readership is the one percent. It makes sense therefore to maintain that real economic injustice is the work of the one-tenth of one percent. "It's not you, dear reader, it's those cads who buy the TImes but don't read my column who are to blame." Magnifying marginal distinctions, dismissing the significant, and excluding the challenging comes with the territory.

As a commentator, Krugman is a Jerry Seinfeld at a time which requires a Bill Hicks. In the second term of the Sanders presidency, I will be happy to read his wry observations about airline food and the latest crazy things Senator Ivanka Trump has been saying. In the meantime…