inequality

Q and A with Jonathan White on In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea

We speak to Jonathan White about his new book, In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea, which investigates how changing political conceptions of the future have impacted societies from the birth of democracy to the present.

On Tuesday 30 January 2024 LSE staff, students, alumni and prospective students can attend a research showcase where Jonathan White will discuss the book.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea. Jonathan White. Profile Books. 2024.

Q: What is the value of examining democracy in terms of its orientation towards, or relationship to, the future?

Q: What is the value of examining democracy in terms of its orientation towards, or relationship to, the future?

My book tries to show how beliefs about the future shape expectations of who should hold power, how it should be exercised, and to what ends. The emergence of modern democracy in Europe coincided with new ways of thinking about time. In the 18th and 19th centuries, emerging ideas of a future that could be different from the present and susceptible to influence helped to spur mass political participation. Movements of the left cast the future as the place of ideals, and “isms” such as socialism and liberalism provided the basis on which strangers could find common cause. Conversely, authoritarians have used the future differently to pacify the public and keep power out of its hands. Projecting democracy, prosperity and justice into the future is one way to seek acceptance of their absence in the present.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, emerging ideas of a future that could be different from the present and susceptible to influence helped to spur mass political participation.

Q: Why is an emphasis on continuation beyond the present essential to the operation of democracy?

Modern democracy is representative democracy, and that gives the future particular significance. Why should people accept the results of elections that go against them? “Losers’ consent” is generally said to rest on the notion that victories and defeats are temporary – there will always be another chance to contest power. The expected future acts as a resource for the acceptance of adversaries and of mediating institutions and procedures. One of today’s challenges is that this sense of continuation into the future is increasingly questioned. Problems of climate change, inequality, geopolitics and social change are widely viewed as so urgent and serious that they remove any scope for error – waiting for the “next time” is not enough. Every political battle starts to feel like the final battle, to be won at all costs. This year’s US presidential election will be fought in these terms and will make clear the stresses it puts on democracy.

One of today’s challenges is that this sense of continuation into the future is increasingly questioned. Problems of climate change, inequality, geopolitics and social change are widely viewed as so urgent and serious that they remove any scope for error

Q: You credit liberal economic thinkers like Adam Smith with “pushing back the temporal horizon”. How did their ideas around the free market treat the future?

In the early Enlightenment, defenders of free trade and commerce tended to emphasise the dividends that could be expected in the short term – peace and stability, for example, and access to goods. But the legitimacy of the market order would be hard to secure if it rested only on immediate benefits. What if conditions were harsh, or wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few? Pioneers of liberal economic thought such as Smith started to promote a longer perspective, allowing them to cite benefits that would need time to materialise, such as advances in efficiency, productivity and innovation. The future could also be invoked to indicate where present-day injustices would be ironed out. What we now know as “trickle-down” economics, in which returns for the rich are embraced on the idea that they will percolate down to the many, entails pointing to the future to defend the inequalities of the present. By invoking an extended timeframe, one can seek to rationalise a system that otherwise looks dysfunctional.

Pioneers of liberal economic thought such as Smith started to promote a longer perspective, allowing them to cite benefits that would need time to materialise, such as advances in efficiency, productivity and innovation.

Q: You cite the 20th-century ascendance of technocracy, of “ideas of the future as an object of calculation, best placed in the hands of experts”. How has this impacted democratic agency?

One way to think about the future is in terms of probabilities – what outcomes are most likely and how they can be prepared for. You find this outlook in business, and in government – especially in its more technocratic forms. It brings certain things with it. A focus on prediction and problem-solving often means focusing on a relatively near horizon – a few years, months, weeks or less – as where the future can be gauged with greatest certainty. And that in turn tends to go with a consciously pragmatic form of politics, less interested in the longer timescales needed for far-reaching change. In terms of the democratic implications, a focus on probabilities tends to elevate the role of experts – economists, for example – as those able to harness particular methods of projection such as statistics. If you turn the future into an object of calculation, it tends to favour elite modes of rule.

An emphasis on prediction is also something that has shaped how politics is covered in the media. Consider the use of opinion polls to narrate change – increasingly prominent from the 1930s onwards – which encourage a spectator’s perspective. Or consider a style of reporting quite common today, whereby a journalist talks about “what I’m hearing in Washington / Westminster / Brussels”. Its focus is on garnering clues about who seems likely to do what, and what they think others will do. The accent is less on the analysis of how things could be, or should be, or indeed currently are, and more on where they seem to be heading. It is news as managers or investors might want it – and politically that often amounts to an uncritical perspective.

Q: You discuss how desires to calculate the future through military forecasting took hold during the Cold War. What are the legacies of this in governmental politics today?

One of the main functions of military forecasting during the Cold War was to second-guess the actions of enemy states – where their weaknesses lay, where they might attack, and so on. That was true in both the West and the East. But forecasting was also applied to the control of populations at home, and not just with an eye to foreign policy. Fairly early on, national security experts started to get involved in public policy and urban planning – think of initiatives such as the “war on crime” launched by US President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. The outlook of the military forecaster began to transfer from the realm of geopolitics to public policy, counterinsurgency and the management of domestic protest, bringing methods of secrecy with it. Today’s forms of surveillance governance are the descendants of these forecasting techniques. And so too are conspiracy theories, which are often based on the idea that some have more knowledge of the future than they let on. Theories of 9/11 that suggest the US government saw the attack coming and deliberately let it happen, or even assisted it, are emblematic.

Q: Why is reducing social and economic inequality important to enable future-oriented political engagement from as many people as possible?

Democratic participation requires the capacity to see the present from the perspective of an imagined better future. But that presupposes the time and capacity for reflection. Those living in insecure conditions typically lack the resources and inclination to turn their eyes to the future. In exhausting jobs, the focus tends to be on getting through the day (or night): the present dominates the future. In precarious jobs or unemployment, people lack control of their lives: the future can look too unpredictable to bother with. Political engagement also depends on a sense that the problems encountered are shared with others. A workplace centred on short-term contracts on the contrary presents individuals with a constantly changing cast of peers. Other things can also undercut a sense of shared fate – personal debt, for instance, or algorithmic forms of scoring (eg, in insurance) that focus on the particularities of individual lives.

In exhausting jobs, the focus tends to be on getting through the day (or the night): the present dominates the future.

This is the sense in which the social and economic changes of the last few decades have fostered the privatisation of the future. The choices of political organisations like parties and movements are crucial in this context. They can either challenge these tendencies, developing that critical perspective on the present and a sense of shared fate – think eg, of a movement like the Debt Collective. Or they can reproduce these tendencies – eg, by treating voters as individuals who want only to maximise their own interests.

Q: What effects can crises have on how governments and citizens conceptualise and act on the future? Are current democratic political systems capable of addressing the climate crisis, the great future-oriented challenge of our time?

Crises tend to engender a sense of scarce time, and in the contemporary state that tends to bring a managerial approach to the fore. Emergencies are governed as one more problem of calculation, with a focus on concrete outcomes that can be traced from the present. The risk is that questions of justice and structural change get marginalised, as considerations that distract from the immediacy of the situation and open too many issues. Emergency government tends to prioritise short-term goals over long-term, and those which are concrete and quantifiable over those which are not.

Climate change too tends to be turned into a problem of calculation in policymaking circles. One sees it with the targets and deadlines invoked. By making net zero carbon emissions an overriding objective, authorities can marginalise considerations no less relevant to human wellbeing and environmental protection – biodiversity, global health and economic equality, for example. This is why some climate scholars see such methods as counterproductive. By emphasising a particular set of variables within a delimited timeframe, targets and deadlines get us thinking more about the near future, crowded with specificities, and less about the further horizon and the more general, incalculable goals that belong to it.

Taking the future seriously meant not hemming oneself in with false precision but setting out clear principles and organising in their pursuit.

The pitfalls of exactitude are something I try to highlight in the book. Not only is it hard to make predictions in a volatile world, but a focus on quantified targets can be counterproductive, since the facts at any moment can be bleak. As the socialists of the late 19th century understood, if the future was to be about radical change pursued over the long term, one could not afford to get lost in the details of the moment. Taking the future seriously meant not hemming oneself in with false precision but setting out clear principles and organising in their pursuit. I think this is a message that still applies. Climate change requires science and precision to grasp, but climate politics requires balancing this with a sense of uncertainty, open-endedness, and the possibility of radical change.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Anna D’Alton, Managing Editor of LSE Review of Books.

When millions face fuel poverty we must redistribute more income and wealth in this country so that all have a chance of flourishing within it

As the Guardian is reporting this morning:

More than 2 million people across the UK will be cut off from their gas and electricity this winter because they cannot afford to top up their prepayment meters, according to Citizens Advice.

The charity said it had made the estimate for what is expected to be its busiest winter ever for helping people who cannot afford to top up, after last year 1.7 million people were disconnected at least once a month.

They added:

In addition, more than 5 million people who are billed by their supplier are in debt, putting them at risk of debt collection or being forced to fit a prepay meter.

These are real measures of a country out of ease with itself. Some within it - our energy companies - are clearly trying to extract more for a basic commodity that is essential to well-being than those who are in need of it can afford. The state is clearly not doing enough to help those in need when figures on disconnections and debt reach the levels noted in that report.

And yet, we hear this morning that the Chancellor has sufficient fiscal headroom (an utterly meaningless term) to consider tax cuts in March.

Those in fuel poverty will not gain much from any tax cut; the poorest never do.

What this country needs is a massive redistribution of wealth so that everyone has a chance to thrive within it. If the country is in trouble - and it is - it is because we systematically deny that opportunity to millions, as this data shows.

That is why the £146 billion that I now suggest that the Taxing Wealth Report might raise - or some part of it - must not be used to pay for the transition that our economy needs to sustainability or to provide better public services but to simply redistribute income and wealth in this country so that all have a chance of flourishing within it.

I will never understand those who might disagree. Why do they hate those without the means to meet basic needs so much?

All they think about is money…

Fred Wright was a cartoonist for the United Electrical Workers of America (UE), from 1949 until 1984. Wright’s cartoons reflected the daily routines experienced by the working men and women: layoffs, discrimination, income inequality, industrial accidents, union-busting, etc. These realities of the class structure of capitalism were the basis for his artistic and activist work. […]

An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

In the second quarter of 2022, the homeownership rate for white households was 75 percent, compared to 45 percent for Black households and 48 percent for Hispanic households. One reason for these differences, virtually unchanged in the last few decades, is uneven access to credit. Studies have documented that minorities are more likely to be denied credit, pay higher rates, be charged higher fees, and face longer turnaround times compared to similar non-minority borrowers. In this post, which is based on a related Staff Report, we show that banks vary substantially in their lending to minorities, and we document an overlooked factor in this difference—the inequality aversion of banks’ stakeholders.

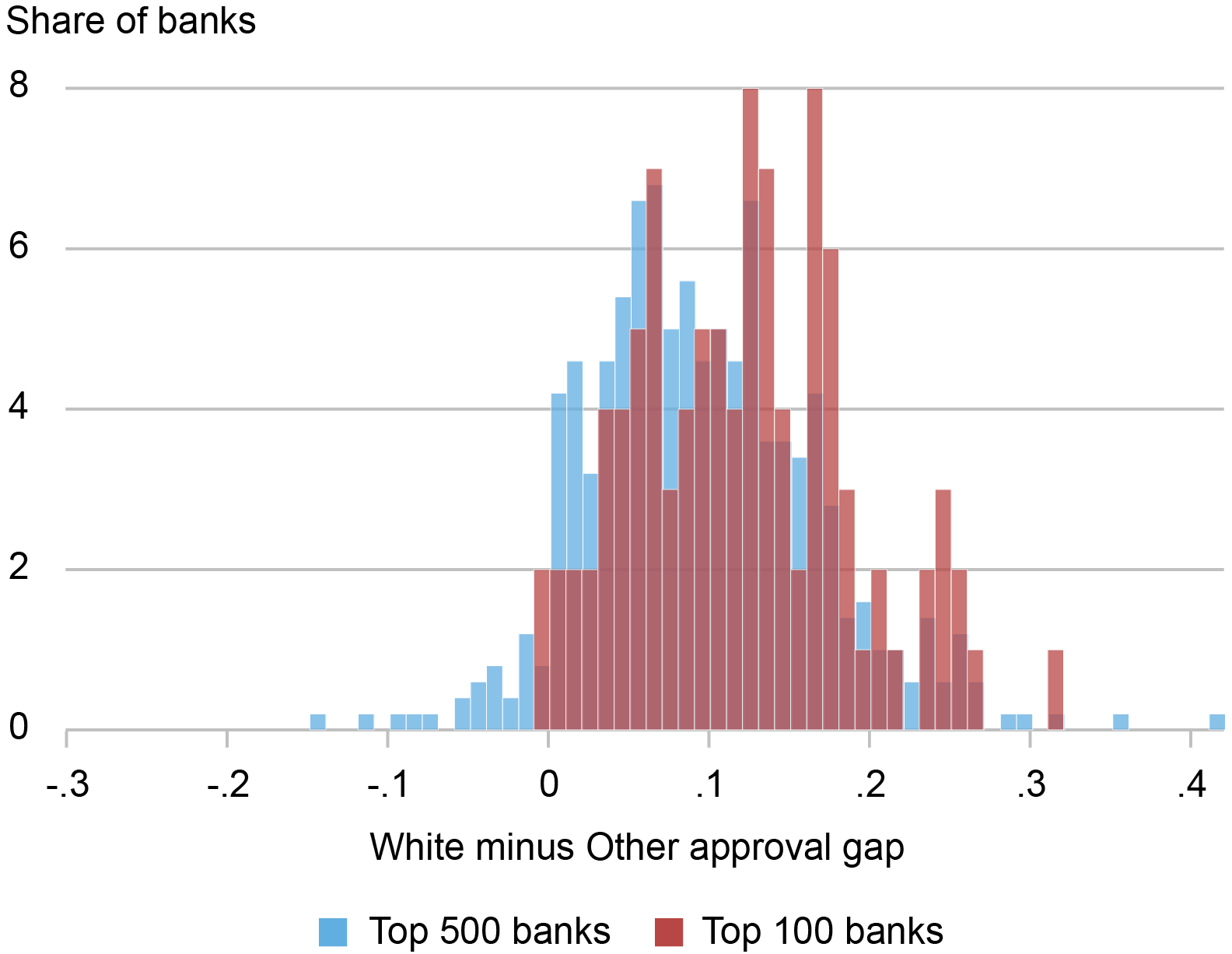

Substantial Differences in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

We use mortgage applications data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act to calculate banks’ lending to minorities. Our data set consists of 114.3 million loan applications received by 838 banks from 1995 to 2019. For each bank and for each year, we calculate the bank approval ratio, defined as the number of mortgage applications approved divided by the number of mortgage applications received.

The difference in lending to minorities across banks is sizable. The chart below shows the distribution of banks’ “approval gaps”—defined as the difference in the approval ratios for mortgage applications made by minority and non-minority borrowers. Such approval gaps tend to be positive (so that approvals are lower for minority applicants) and heterogenous across banks. Crucially, this variation persists within a narrow geographical area (such as county or census tract), suggesting that banks with small approval gaps are not systematically located in areas of the country where minorities have a relatively low credit risk.

Banks’ Lending to Minorities Varies Substantially

Source: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data.

Notes: The chart shows the distribution of approval gaps, defined as the mortgage application approval ratio for white applicants (HMDA race code 5) minus the mortgage application approval ratio for other applicants (HMDA race codes 1-4). Top 500 and top 100 banks are defined based on the number of applications received. The sample period is 1995-2019.

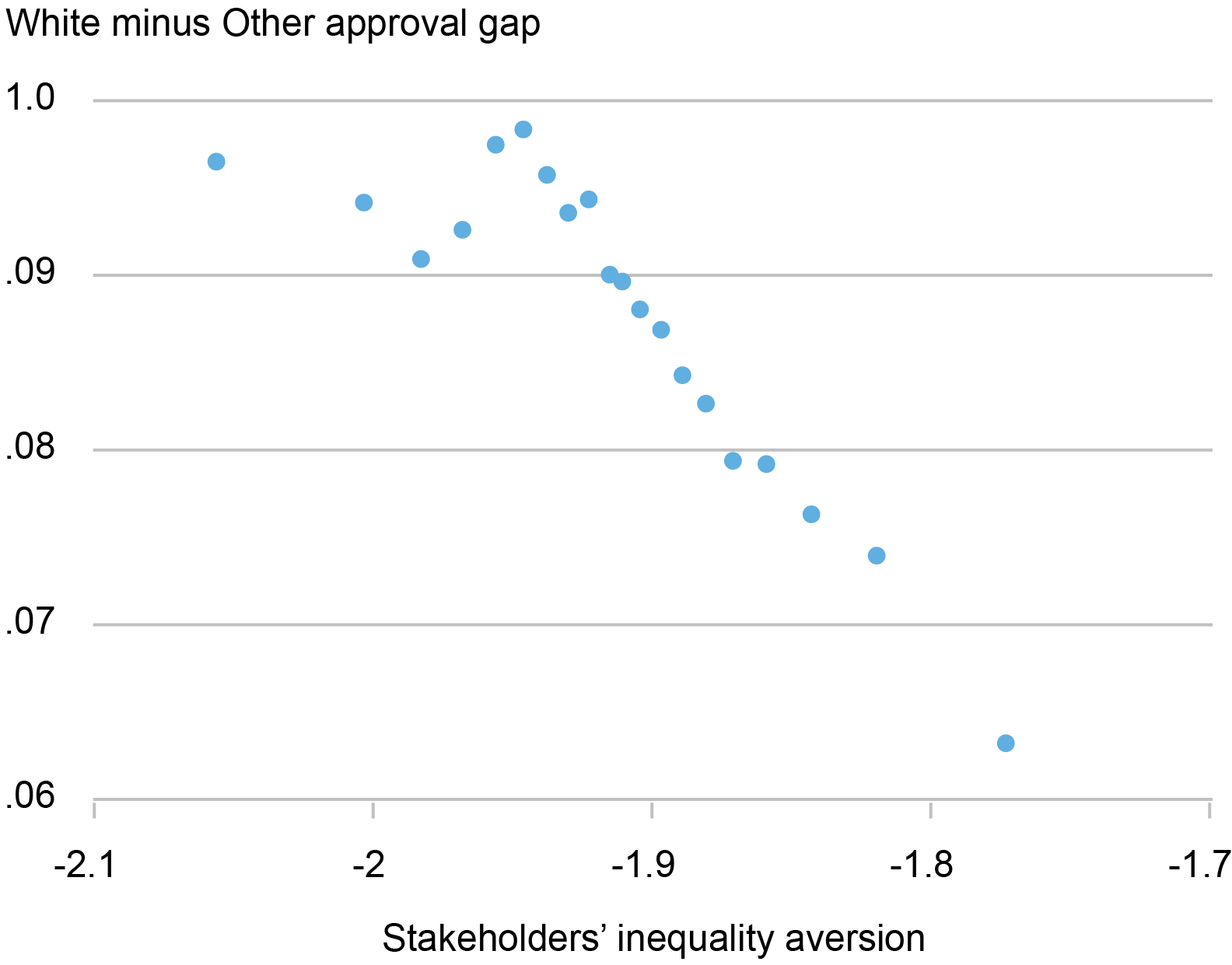

An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

Measuring stakeholders’ inequality aversion is challenging. It requires both a definition of stakeholders (which include, for example, depositors, borrowers, employees, and executives) and a measure of their preference for equal outcomes, resources, and opportunities. Given that bank stakeholders are mostly local, we calculate bank inequality aversion using a survey question on the desired level of government assistance to minority households from the General Social Survey (GSS), a nationally representative survey conducted since 1972 and widely used in academic studies.

Specifically, we use a survey question that asks whether “we’re spending too much money, too little money, or about the right amount of money on assistance to Black households.” Survey respondents can choose one of these three options, coded with the numbers 1, 2, and 3. We then calculate, for each bank, the weighted average of these responses, using the fraction of deposits that each bank has in the area where the respondent is located as weights.

It’s important to note that our analysis is not based on direct information about any bank’s depositors, board of directors, or management, or anything else specific about a bank other than the location of its branches. In the absence of information about banks’ actual stakeholders, we assume that the inequality aversion of the respondents who live in the area where a bank has a branch presence is representative of the preferences of its stakeholders.

With these caveats in mind, we find that banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders by our measure tend to have smaller approval gaps, as shown in the chart below. The data are analyzed within census tracts, thus ruling out that this negative correlation is entirely due to banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders operating in areas where minorities have a lower credit risk. Similarly, within census tracts, banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders do not systematically receive applications from higher-income minority borrowers, suggesting that minority borrowers with lower credit risk do not systematically apply for mortgages with more inequality-averse banks.

Inequality-Averse Banks Lend More to Minorities

Sources: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data; MIT Election Data and Science Lab; FDIC summary of deposits.

Notes: This binscatter plots banks’ non-minority minus minority approval gaps (the mortgage application approval ratio for white applicants (HMDA race code 5) minus the mortgage application approval ratio for other applicants (HMDA race codes 1-4)) on the y-axis against stakeholders’ inequality aversion (multiplied by minus one) on the x-axis. The analysis controls for census tract–year fixed effects. Banks are grouped in bins for readability.

How Might Stakeholders Affect Banks’ Lending?

So, how might an institution’s stakeholders impact its lending decisions? Likely indirectly. A possible channel is that, in their lending decisions, banks consider the inequality aversion of the counties in which they operate so as to attract and retain their (mostly local) stakeholders. Consistent with this mechanism, we find that banks that have been hit with a Department of Justice (DOJ) case for discrimination in mortgage lending experience a sizable drop in deposits, one that is particularly pronounced in counties with high inequality aversion. This result, detailed in our Staff Report, is consistent with recent anecdotal evidence on how stakeholders’ social considerations affect financial institutions.

Importantly, the higher lending to minorities of banks with inequality-averse stakeholders has a small and positive effect on performance, suggesting that it is not a manifestation of costly “goodness.” Specifically, the narrowing in approval gaps between minority and non-minority borrowers is followed by a small improvement in banks’ mortgage book quality and a small increase in overall bank profitability.

Final Thoughts

Our insight on the interaction between stakeholders’ inequality-aversion and banks’ lending to minorities is related to the discussions about lending discrimination and racial and ethnic disparities in housing. On the one hand, such inequality aversion might alleviate lending discrimination based on race and neighborhood characteristics. On the other hand, it might drive banks to specialize in different segments of the residential mortgage market. One interesting avenue of future research is understanding to what extent credit access for minorities might differ across the country based on the inequality aversion of local stakeholders.

Matteo Crosignani is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Hanh Le is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Illinois Chicago.

How to cite this post:

Matteo Crosignani and Hanh Le, “An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 10, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/01/an-overlooked-fact....

Stakeholders’ Aversion to Inequality and Bank Lending to Minorities

![]()

Economic Inequality: A Research Series

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

The lessons to learn from Martin Luther King

This article to mark Martin Luther King Day in the USA, which is on 15 January, was written by an old friend of mine, Ben Phillips. We worked on tax justice issues together when he worked for UK based NGOs. He is now the Director of Communications for UNAID. He is the author of an excellent book on campaigning, How to Fight Inequality.

This article was first published on the IPS News service and is reproduced here with Ben’s permission.

All through this week, leading up to January 15th, the world will commemorate Martin Luther King. In a world as wounded as ours is today, the lessons of his life’s work offer a vital opportunity for healing.

But the opportunity to hear his message continues to be obstructed: too many of the soundbites of TV pundits and the tweets of politicians are, once again, not distilling the insights of Dr King, but are serving instead to obscure a library of wisdom behind wall-to-wall repetition of the same few lines, extracted from their context, of one speech.

This is not a mistake, it is a tactic, and we owe it not only to the legacy of Dr King but to the future of our world to ensure that his authentic message is shared.

The true message of Martin Luther King is not a saccharine call for quietude or acceptance, but an insistence on being, as he put it, “maladjusted to injustice.” It represents not an idle optimism that things will get better but a determined commitment to collective action as the only route to progress.

When Dr King said “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice”, he didn’t mean this process is automatic; as he noted, “social progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of people.”

And he was clear that advancement of progress requires the coming together of mass movements, “organizing our strength into compelling power so that government cannot elude our demands.”

Justice, Dr King taught, is never given, it is only ever won. This always involves having the courage to confront power. Indeed, he noted, the greatest stumbling block to progress is not the implacable opponent but those who claim to support change but are “more devoted to order than justice.” As he put it, “frankly I have yet to engage in a direct action movement that was ‘well-timed’ in the view of those who have not suffered unduly; this ‘wait!’ has almost always meant ‘never.’”

When the civil rights movement’s 1962 Operation Breadbasket challenged companies to increase the share of profits going to black workers and communities, it was only after the movement showed that they could successfully organize a boycott that those companies, in Dr King’s words, “the next day were talking nice, were very humble, and [later] we signed the agreement.” As he noted when challenged by “moderates” who asked why he needed to organize, “we have not made a single gain without determined pressure…freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor, it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Advancing progress, he emphasized, involves challenging public opinion too. Organizers cannot be mere “thermometers” who “record popular opinion” but need to be “thermostats” who work to “transform the mores of society”. In 1966, for example, a Gallup Opinion poll showed that Dr King was viewed unfavourably by 63 per cent of Americans, but by 2011 that figure had fallen to only four per cent.

Often, people read the current consensus view back into history and assume that Dr King was always a mainstream figure, and imagine, falsely, that change comes from people and movements who don’t ever offend anyone.

Dr King’s vision of justice was a full one. It called not only for the scrapping of segregation, but for taking on “the triple prong sickness of racism, excessive materialism and militarism.” He challenged the “economic conditions that take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few” and noted that “true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar, it understands that an edifice which produces beggars, needs restructuring.”

He spoke out against war not only for having “left youth maimed and mutilated” but for having also “impaired the United Nations, exacerbated the hatreds between continents, frustrated development, contributed to the forces of reaction, and strengthened the military-industrial complex.”

He noted how “speaking out against war has not gone without criticisms, there are those who tell me that I should stick with civil rights, and stay in my place.” But he insisted that he would “keep these issues mixed because they are mixed. We must see that justice is indivisible, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

When I went to Dr King’s memorial in Atlanta I did so to pay my respects at his tomb. But arriving at the King Center I found a vibrant hub of practical learning, at which activists and organizers working for justice were revisiting Dr King’s work and writings not as history that is past but as a set of tools to help understand, and act, in the present.

Together, we reflected not only on his profoundly radical philosophy, but also on his strategies and tactics for advancing transformational change. Conversations with Dr King’s inspirational daughter, Bernice, were focused not on her father’s work alone; instead, she asked us what changes we were working for, and how we were working to advance them.

This year, on 10th January, the King Center is hosting a Global Summit, a series of practical conversations accessible to everyone, for free, online. I’m honoured to be panelist. It is open for sign ups here.

“Those who love peace,” noted Dr King, “must learn to organize as effectively as those who love war.” And he even guided us how.

Homelessness among racialized persons

Chapter 7 of my open access textbook has just been released. This chapter focuses on homelessness experienced by racialized persons.

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter can be found here (in English):

https://nickfalvo.ca/homelessness-among-racialized-persons/

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter in French can be found here:

https://nickfalvo.ca/litinerance-chez-les-personnes-racialisees/

The full chapter can be found here (English only):

https://nickfalvo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Falvo-Chapter-7-Racializ...

All material related to the book is available here: https://nickfalvo.ca/book/

Homelessness among racialized persons

Chapter 7 of my open access textbook has just been released. This chapter focuses on homelessness experienced by racialized persons.

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter can be found here (in English):

https://nickfalvo.ca/homelessness-among-racialized-persons/

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter in French can be found here:

https://nickfalvo.ca/litinerance-chez-les-personnes-racialisees/

The full chapter can be found here (English only):

https://nickfalvo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Falvo-Chapter-7-Racializ...

All material related to the book is available here: https://nickfalvo.ca/book/

Measuring Price Inflation and Growth in Economic Well‑Being with Income‑Dependent Preferences

How can we accurately measure changes in living standards over time in the presence of price inflation? In this post, I discuss a novel and simple methodology that uses the cross-sectional relationship between income and household-level inflation to construct accurate measures of changes in living standards that account for the dependence of consumption preferences on income. Applying this method to data from the U.S. suggests potentially substantial mismeasurements in our available proxies of average growth in consumer welfare in the U.S.

These insights and results are based on my recent research paper coauthored with Xavier Jaravel of the London School of Economics, which is forthcoming at the Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Background

Economic theory shows that we can approximate changes in living standards using straightforward formulas known as price and quantity indices. These indices combine observed data on changes in the quantities of what we consume and the prices of those items, and are widely used by statistical offices around the world to construct measures of overall inflation in the cost of living and growth in living standards. However, this approach hinges on a crucial assumption—that the composition of what we want to buy does not shift when our incomes do (see, for example, Diewert 1993). Unfortunately, this simplifying assumption, known as homotheticity or income invariance, does not match up with a host of real-world evidence on the dependence of consumption patterns on consumer income, going as far back as the work of Engel (1857). Recent evidence on inflation inequality—the strong relationship between income and household-level measures of inflation—underscores the importance of this problem.

Insight and Method

A conceptually coherent way to measure living standards is to fix a set of prices and calculate the monetary expenditure needed, under these prices, to achieve any level of consumer welfare as it changes over time. Let us refer to this concept as real consumption, to distinguish it from the nominal expenditure of the consumer under changing prices. For instance, consider a case where all prices rise at the same 2 percent rate from one year to the next due to general inflation. Here, a consumer whose nominal expenditure has risen by 5 percent only experiences a 3 percent increase in real consumption, if we fix the prices in the initial or the final year. The key question is how to calculate the corresponding measures of inflation and real consumption growth in real-world settings in which changes in prices vary across different goods and services.

If consumer preferences are income-invariant, everyone consumes the same basket of goods and services regardless of their income level. Over time, households adjust whether to consume more or less of each good or service based on how its price changes relative to others, but these adjustments are the same for everyone. Conventional price indices tell us how to average these price changes using the expenditure shares of different goods and services, and theory tells us we need to deflate the growth in nominal expenditure based on the value of this average, which is the standard measure of inflation.

In reality, households choose different baskets of goods and services that systematically depend, among other things, on their income. Therefore, we find different inflation measures for different households when we compute the price indices using each household’s own expenditure shares, something that should not happen under the conventional assumption of income invariance. In the data, we often find lower inflation measures for richer households, meaning that prices rise more slowly for luxuries—i.e., items that are more heavily purchased by richer consumers (see, for example, Hobijn and Lagakos 2005, McGranahan and Paulson 2006, Jaravel 2019, Avtar et al. 2022, and Chakrabarti et al. 2023). Therefore, these items are becoming relatively cheaper than the others over time. This implies that, if we fix the initial prices as our basis for measuring real consumption, households that experience rising income will be shifting their consumption toward items that are accumulating relative price declines. In other words, sustained inflation bias toward necessities—goods and services favored by poorer households—means that we need relatively lower rates of growth in nominal terms to maintain the same rate of growth in real consumption. Thus, when income is growing, consumers are actually better off than that suggested by all available measures of real consumption. The conventional measures of inflation and real consumption miss this mechanism altogether. This is even true of the more recent work on inflation inequality, partially cited above, that relies on household-specific price index formulas but does not explicitly account for income dependence.

As it turns out, there is a relatively easy fix for this problem. We can correct for the effects of this income dependence in preferences simply by estimating the relationship between household income and household-specific price indices. The slope of this relationship leads to a correction factor that we need to apply to the nominal expenditure growth after it is deflated by the household’s own price index. This method is fairly easy to implement and only requires access to widely available surveys of consumption expenditure at the household level. Moreover, it can be generalized to extend to other household characteristics, such as age, family size, and education, that (1) matter for the composition of their consumption expenditure, and (2) potentially vary over time at the household level.

Application to the U.S. Data

In the paper, we apply our approach to data from the United States and quantify the magnitude of the bias in conventional measures of real consumption growth that ignore the effects of income dependence in household preferences. We build a new linked dataset providing price changes and expenditure shares at a granular level from 1955 to 2019, across the different percentiles of household (pretax) income. This dataset combines several data sources, primarily drawing from disaggregated data series available from the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX). This new linked dataset allows us to provide evidence on the inequality in inflation over a long time horizon, thus extending prior estimates that have focused on shorter time series.

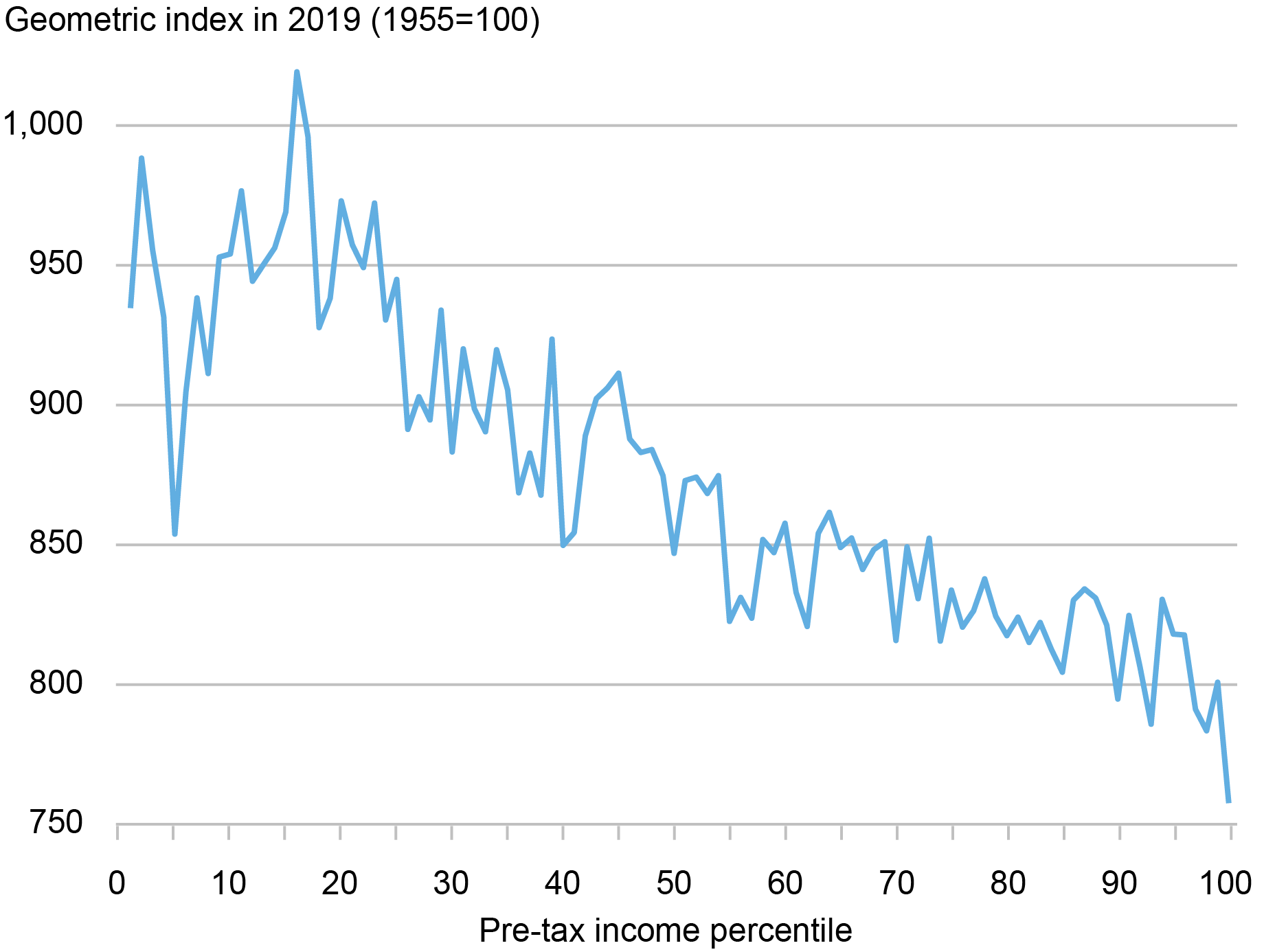

Computing inflation using income-percentile-specific price index formulas, we find that inflation inequality is a long-run phenomenon. For instance, as the chart below shows, we find that cumulative inflation from 1955 to 2019 varies substantially for households with different levels of income: while prices have inflated by a factor of around 10 for the bottom income groups, they have inflated by a factor closer to 8 at the top of the income distribution. The gap in inflation experienced by different income percentiles is sizable when compared to the overall size of inflation over the period. As such, when we look into the past from the perspective of today’s prices, we observe that (1) households were on average poorer sixty-five years ago—that is, they had stronger preferences for necessities; and (2) necessities were cheaper relative to luxuries. These empirical patterns imply that consumer welfare was higher sixty-five years ago when accounting for the dependence of preferences on income.

Inflation Inequality over the Long Run

Source: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: This chart shows the patterns of inflation inequality in the data. It shows the cumulative inflation rates between 1955 and 2019 by pretax income percentiles.

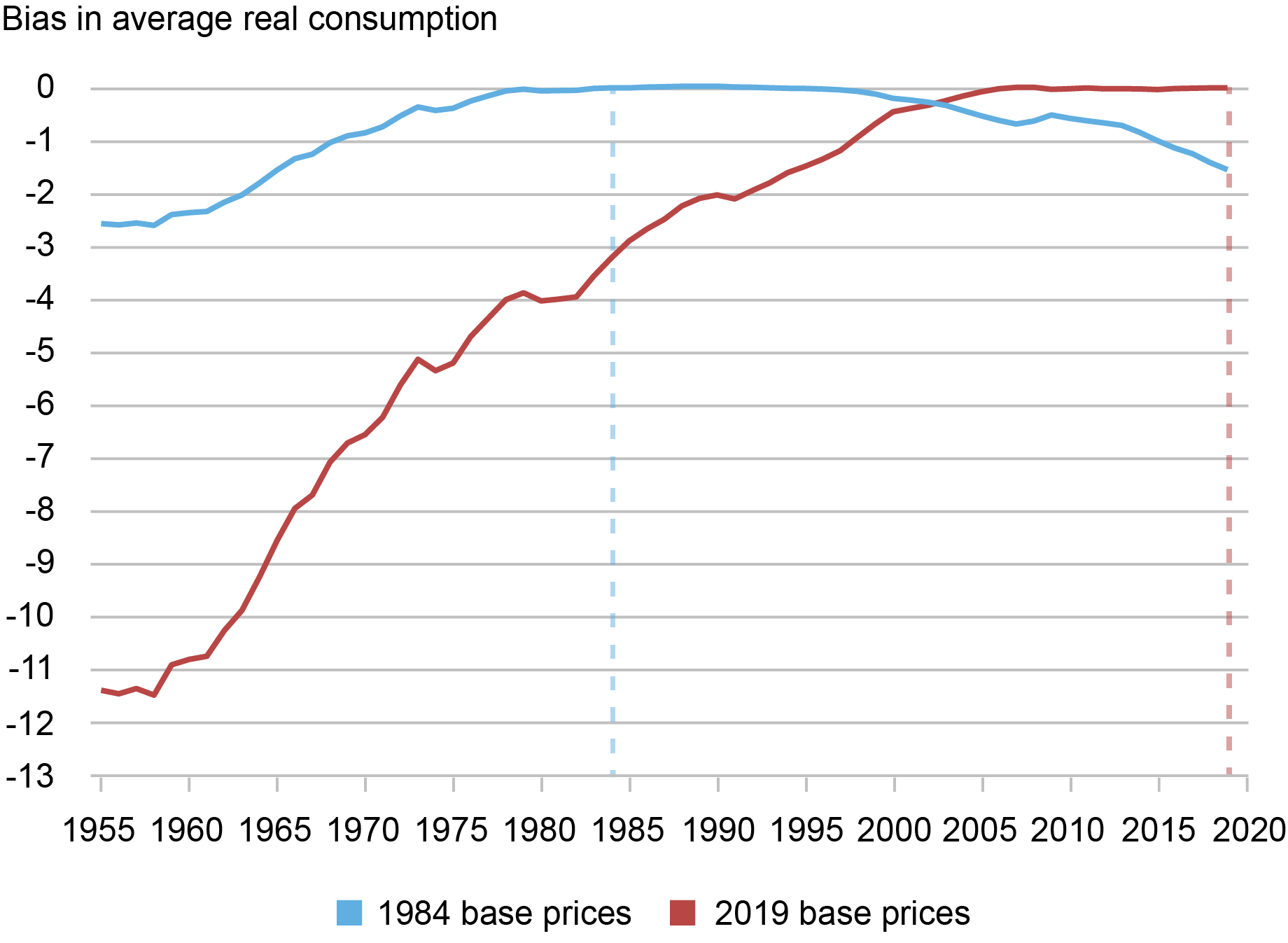

When we apply our new method to this data, we find that the magnitude of the correction in measured welfare growth due to the effect of income-dependent preferences can be large. For example, as the chart below shows, by fixing prices in 2019 as the basis of defining real consumption, we find that the uncorrected measure underestimates average real consumption (per household) in 1955 by about 11.5 percent. Note that, by definition, the error is zero in the base year and accumulates over time as we move in time—in this case backward—away from the base year. For comparison, we also show the results if we fix prices in 1984. In this case, the bias is smaller simply because it accumulates over a shorter time period, as we move away from the base year in our data.

Bias in Conventional Measures of Average U.S. Real Consumption (1955-2019)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: This chart reports the biases in the level of average real consumption per household in conventional measures of real consumption, when compared against the corrections implied by our method, under two choices for the fixed prices as the base for calculation of real consumption: prices in 1984 and in 2019.

Of course, bias in measuring the level of real consumption leads to corresponding biases in the estimated growth. As the chart above already indicates, if we fix prices in the most recent year (2019), the conventional estimates overestimate the rate of growth in average real consumption due to the negative bias in the levels. In particular, the uncorrected measure of cumulative real consumption growth is 270 percent over the entire 1955-2019 period, or 2.07 percent growth annually. In contrast, with our correction for income dependence and under 2019 base prices, cumulative consumption growth falls to 232 percent, or an annualized growth rate of 1.89 percent per year. Thus, in this case we find that the annual growth rate from 1955 to 2019 is lowered by 18 basis points (2.07 percent − 1.89 percent).

Note that, since the conventional measure always underestimates the level of real consumption, the sign of the error in measured growth of real consumption depends on the choice of the base prices. For instance, if we instead fix 1984 prices as our base, the chart shows that the conventional measures in fact underestimate the growth in real consumption between 1984 and 2019. In other words, since preferences are income-dependent, measured growth in real consumption should in principle depend on the choice of fixed prices to express the measure.

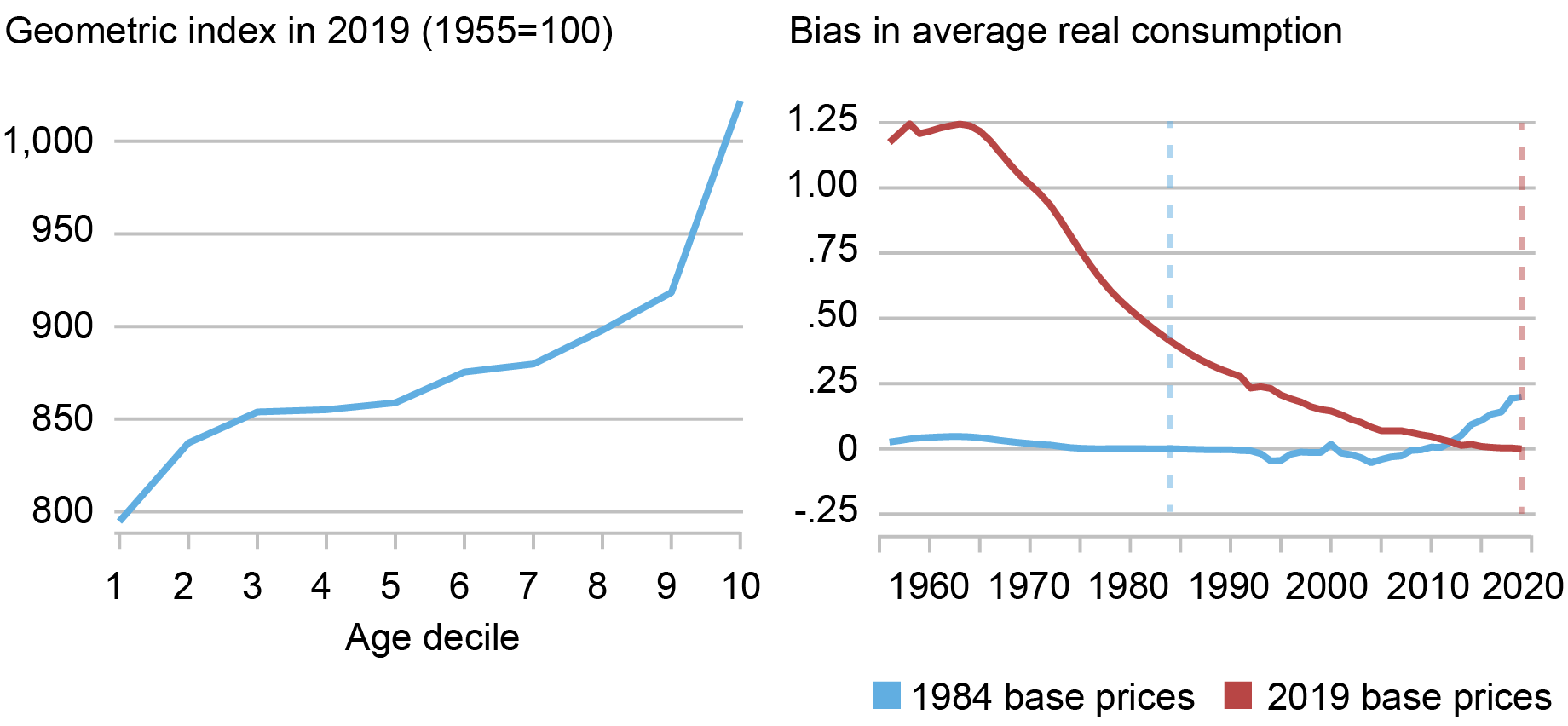

Finally, we also apply our generalized method to quantify the adjustment to average real consumption implied by consumer aging in the United States. In this case, we reconstruct our measures of inflation by deciles of age and income by, first, defining ten deciles of the (pretax) income and, then, computing ten age deciles within each income decile. Using this data, as the chart below illustrates, we document a strong positive relationship between consumer age and inflation, which alters the measurement of real consumption because the average consumer age increases over time. We find that the implied adjustments to real consumption are economically meaningful but much smaller than the correction due to income dependence, which justifies our focus on the latter.

Consumer Aging and Real Consumption (1955-2019)

Sources: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: The left panel of the chart reports the cumulative inflation in the United States, from 1955 to 2019, for each decile of age. The right panel reports the implied bias in the average level of real consumption per household in conventional measures of real consumption, when compared against the corrections implied by our method due to aging, under two choices for the fixed prices as the base for calculation of real consumption: prices in 1984 and in 2019.

Conclusion

Our results may have important implications for the way in which national statistical agencies around the world construct measures of inflation and real economic value. In particular, the empirical results presented above suggest an approach that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) can use, based on already available data, to construct improved measures of real consumption growth and inequality in the U.S. In addition to improving the measurement of long-run growth and inflation inequality, our new approach can have important policy implications, such as the indexation of the poverty line and a more efficient targeting of welfare benefits. This approach also provides a blueprint for distributional national accounts (Piketty et al. 2018) that account for inflation inequality and income dependence in household preferences.

Danial Lashkari is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Danial Lashkari, “Measuring Price Inflation and Growth in Economic Well‑Being with Income‑Dependent Preferences,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 8, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/01/measuring-price-in....

Was the 2021-22 Rise in Inflation Equitable?

Inflation Disparities by Race and Income Narrow

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Danny Kruger is wrong: we got a much more conservative country under the Tories. The inequality in excess deaths proves it.

As the Guardian notes this morning:

Danny Kruger, a leading backbencher and founder of the increasingly influential New Conservatives group, said the Conservatives risked being ejected from power this year having left the country “sadder, less united and less conservative” than they found it.

Kruger is, of course, as wrong on this as he is on everything else I have ever heard him talk about. Another Guardian report on work on the impact of inequality in the distribution of excess deaths in the UK over much of their period in office is clear evidence of that. As his work found, excess deaths were distributed by income decile as follows:

Tory policies worked, without a doubt. We did have a Conservative country. Disadvantaged people died as a result, which is a trend that the Party seems determined to continue going forward.

We did not get a less conservative country under the Tories. We got a more conservative one. It's just that, as ever, Kruger looked in the wrong place to find his evidence. Looking at his privileged mates was an insufficient sample base from which to draw conclusions, but that's all Tories do now, as Sir Howard Davies also proved last week.

Solar Pumps Are Empowering Women Farmers in India

Narrow roads lead to Harpur, flanked by small houses with expansive courtyards on both sides. Harpur is a small village perched at one corner of the Bandra block in Muzaffarpur district in the Indian state of Bihar, and though it may look like any other rural village, it is home to a group of women farmers who are at the forefront of a revolutionary change.

Historically, this region has grappled with water scarcity, which sharply limited the crops that farmers could cultivate. But since women-led self-help groups stepped in and installed solar pumps to provide affordable clean energy for irrigation, the scenario has changed dramatically. And along the way, these groups are challenging traditional gender norms, making women farmers a catalyst for climate adaptation.

The post Solar Pumps Are Empowering Women Farmers in India appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.