wages

Introducing the Salary Cap Act

by Daniel Wortel-London

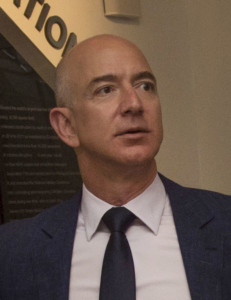

Obscene salaries are no longer sustainable and should be illegal. (Justin Pacheco, Wikimedia)

The daily news regularly features commentary about the outrageous and growing income inequality in the USA. The data support the outrage:

- In 1965, the CEO-to-worker salary ratio at the average U.S. company was 21-to-1. Today that ratio is 344-to-1.

- In 2022, CEO pay at 100 S&P 500 companies averaged $15.3 million, while median worker pay averaged only $31, 672, according to an Institute of Policy Studies analysis.

- Since 1978, CEO pay has increased 1,460 percent.

Many reasons can be cited for opposing large discrepancies in pay, including depressed morale of employees, diminished firm productivity, and widened gender and racial disparities. Another reason is their effect on the environment. High salaries tend to increase environmental impacts. And high pay, particularly high CEO pay, is dependent on—but also drives—the economic growth that is creating today’s societal and environmental crises.

To counter inequality in the USA, CASSE proposes adoption of a Salary Cap Act (SCA). The Act would create salary caps by major occupational sector, as Brian Czech proposed in Supply Shock. Almost no expansion of the Tax Code is entailed. The SCA would simply prohibit the issuance of salaries beyond the prescribed proportions (described below), making it a crime for employers to issue exorbitant salaries.

Exorbitant Salaries and Environmental Degradation

Generating money entails agricultural and extractive activity at the trophic base of the economy. Therefore, the need to pay exorbitant salaries results in more environmental degradation than paying for lesser salaries. Imagine, for example, the ecological footprint required to pay Elon Musk compared to a minimum-wage worker.

Highly paid individuals are more likely to purchase resource-intensive luxury goods, too. This is one reason why the USA’s top one percent of income earners was responsible for 23 percent of the growth in global carbon emissions between 1990 and 2019. And income inequality leads to inequality in political power, which helps CEOs lobby for policies that promote unsustainable growth.

Limiting the environmental impact of the economy entails limits on high salaries. (Richard Hurd, Creative Commons 3.0)

High salaries drive growth in less obvious ways as well. At many corporations, CEO compensation includes a generous grant of stock and stock options. These sweeteners motivate CEOs to strive for company growth, then use profits to buy back company stock, which raises its price and enriches the CEO even further.

For example, the compensation of oil company executives is intimately linked to exploring for new fields, extracting fossil fuels, and promoting consumption of their fuels and services, activities that contribute to the growth of the firm. As Richard Heede of the Climate Accountability Institute observes, “executives have personal ownership of tens or hundreds of thousands of shares, which creates an unacknowledged personal desire to explore, extract and sell fossil fuels.”

Moreover, high CEO compensation through stock options and bonuses encourages companies to take a short-term perspective that can involve boosting stock prices quickly through shortsighted sales or risky investments. The Enron scandal, for example, involved CEOs trying to quickly raise stock prices in pursuit of bonuses. Selfish and short-sighted decisions like these can take a serious environmental toll, and are disastrous at a time when companies should be committed to the long-term health of our planet.

Drivers of Unequal Pay

CEO pay has increased extensively in part because companies have grown larger and wealthier, which allows them to offer fatter salaries. It’s also because CEOs have increased their leverage over corporate boards and can therefore set their own pay more easily. But the greatest reason is because CEOs are compensated differently than ordinary workers: Some 80 percent of CEO compensation in 2021, for example, derived from vested stock awards and exercised stock options rather than “ordinary” salaries. CEOs are thus able to negotiate salaries that are orders of magnitude higher than the salaries of workers paid through more conventional means.

Policymakers have a deep toolbox for addressing pay inequality. They can, for example, ban or tax stock buybacks or deny public contracts to companies with excessively high pay inequalities. Measures like these are now law. The Inflation Reduction Act placed a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks, while San Francisco and Portland, Oregon have taxed companies with large CEO-worker pay gaps. Inspiration comes from outside the USA as well. The European Union will assist in bailing out failed banks only when their pay ratios are 10-to-1 or less.

Franklin Roosevelt called for a 100 percent tax on annual incomes above $1.2 million (in 2022 dollars). (Elias Goldensky, Public Domain).

But another, more direct remedy for pay inequality is salary caps. We’ve seen such caps in professional sports leagues for decades, including every major league in the USA except Major League Baseball. These caps are much higher than those prescribed in the Salary Cap Act presented below, but they achieve analogous purposes. Leagues use caps to keep overall costs down and ensure a competitive balance among teams. The USA would use salary caps to for purposes of social equity, but also to keep environmental impact at a lower, more sustainable level.

Salary caps, along with caps on wealth and other forms of income, have been proposed by various economists and progressive policymakers, occasionally with public success. A referendum was held in Switzerland in 2013 to cap executive incomes; while unsuccessful, it emboldened major candidates in France and England to endorse similar salary caps. And campaigns for wealth and income caps have taken various forms in U.S. history, from Huey Long’s “Share our Wealth” campaign to Franklin Roosevelt’s call for a 100 percent tax on high incomes during World War II.

In the spirit of these efforts, CASSE proposes the Salary Cap Act.

The Salary Cap Act

The Salary Cap Act is designed to curb exorbitant salaries for purposes of social equity and environmental health. Salary caps are set and enforced by the Department of Labor. A separate provision addresses pay for self-employed workers.

The SCA defines “salaries” as wages, bonuses, tips, and other forms of compensation specified under Section 3401(a) of the Internal Revenue Code. This broad definition is meant to encompass forms of compensation, such as corporate stock options, which are not traditionally classified as “salaries.”

Section 4 describes the target and structure of the salary caps. The Secretary of Labor sets the caps for each of the 23 major occupational groupings in the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) Codes maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The caps are set, and updated annually, to correspond to 1.8 times the salary of the 90th percentile of employees for each occupational grouping. (In other words, maximum salaries in each occupational grouping are 80 percent higher than the salary at which 90 percent of salaries in the grouping are lower and ten percent are higher.)

For example, the annual salary cap for managerial occupations would be set at $400,000, while the cap for food preparation occupations would be set at $81,270. Salary disparities would remain, but they would be far lower than the disparity today. The average CEO-to-worker pay gap across occupational categories is currently 344-to-1. Under the SCA, the ratio would be roughly 7-to-1.

We can respect planetary boundaries, or we can have billionaires, but not both. (Adrian Cadiz, Wikimedia)

Meanwhile, traditional and reasonable salary discrepancies among professions are still respected. For example, licensable occupations that require extensive training or years of graduate school warrant a higher range of salaries than those for occupations requiring little training or education.

The value of 1.8 in the maximum salary formula is chosen because the salary of the President of the United States is currently 1.8 times the 90th percentile of CEO salaries. We do not believe a CEO deserves to be paid more than the president. Still, the SCA’s maximum salary formula offers plenty of room to reward superior performance while curbing the social and environmental distortions of exorbitant salaries.

Section 5 describes how the Office of Labor-Management Studies in the Department of Labor will enforce the SCA. The Office will have the power to petition a court if it believes the Act has been violated. Companies found guilty will face criminal penalties of up to $100,000,000, imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, or both.

A concluding section requires net earnings from self-employment or employee ownership in excess of $400,000 be taxed at 100 percent. Salaries derived from self-employment are not included in the NAICS SOC codes, so it is necessary to “cap” these earnings through taxation rather than salary caps.

The SCA is designed to be both a stand-alone bill and a component of the larger Steady State Economy Act. It will not, by itself, end wealth inequality or ecological overshoot. But it will help apply brakes on incentives that drive economic firms to grow the economy beyond our planet’s carrying capacity.

We also encourage the voluntary adoption of salary caps prior to passage of the SCA. In addition to contributing to the social and environmental purposes of the SCA, such voluntary caps provide a boost to employee morale and cut costs for small businesses and nonprofit organizations.

The Salary Cap Act may be revised pursuant to reader responses and the input of CASSE allies.

Daniel Wortel-London is a CASSE Policy Specialist focused on steady-state policy development.

The post Introducing the Salary Cap Act appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Merseysiders protest government moves to replace skilled medics with less skilled

Demonstrations continue against Tory ‘downskilling’ of the NHS to increase profits

Members of the Merseyside Pensioners Association (MPA) joined health workers on Tuesday to protest outside a meeting of the Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care (ICS) board meeting against plans to cut NHS costs by reducing skill levels in the health service in a copy of unequal and heavily-privatised US healthcare.

The protest and meeting were held at the Floral Pavilion in Wirral’s New Brighton. The MPA joined a large crowd of Wirral Clinical Support workers and Unison members who have been demanding better pay. MPA members were protesting against the downskilling of medical professionals – a move under the so-called NHS Workforce Plan to replace doctors, midwives, nurses, anaesthetists and other highly-qualified workers with cheaper, less qualified staff to pad NHS staff numbers and reduce wage cost, allowing private health companies to provide services at greater profit.

One MPA campaigner told Skwawkbox:

Forcing or encouraging staff to work beyond their competencies is dangerous for patients and staff. NHS campaigners have been highlighting downskilling, professional deregulation, working beyond competencies and similar government moves for several years. It is not accidental, nor is it a response to “shortages of doctors”, “ageing population “, “bed blocking” or “underfunding” – these terms are all propaganda put out to justify the deliberate systematic destruction and withdrawal of the NHS to benefit big business & increase profit.

Some of us went into the meeting, raised questions about the difficulty and hostile processes involved in booking a GP appointment, the difficulty getting to see an actual GP rather than a Physician Associate [a position carrying out medical duties with only two years’ basic training] or other staff member and the lack of continuity that means we rarely see the same person twice.

We told the Board that we want to see fully-qualified medical professionals, that the right people with the right skills for the right job are fully-qualified doctors, anaesthetists etc. The Assistant CEO told us they have bought a new ‘cloud telephony’ service but that there won’t be any increase in GPs or Practitioners in GP surgeries, therefore we assume no increase in appointments either!

So the response appears to be they’ll just move the deckchairs on the Titanic around in a different manner! A longwinded way of saying they had wasted money on a new phone service presumably so you can more easily be told there are no GP appointments. At the ICS Annual General Meeting/ICB meeting last year an actual GP pointed out that without more GPs/appointments, changing the telephone system wasn’t going to help.

A further campaign meeting will take place on Friday 23 Feb at Liverpool’s socialist bar, the Casa:

The government’s use of ‘associates’ instead of fully-qualified medics has already been linked by coroners to at least two avoidable deaths.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

Labour front bench takes £650k from health privateers – more than Tories

Starmer and co rake in cash from private health donors – twenty-five percent more than the Tories

Keir Starmer and his front bench MPs have taken almost £650,000 from private health companies, according to a compilation of their declarations of MPs’ interests.

The totals accepted by MPs in Starmer’s Shadow Cabinet between 2020 and 2023 are:

- Keir Starmer £157,500

- Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting £193,225

- Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper £231,817

- Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves £14,840

- Deputy Labour leader Angela Rayner £50,000

- Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy £1,640

- Total £649,022

Figures compiled by David Powell

The total accepted by Labour beats similar donations to the Tories by around twenty-five percent. Starmer and his health spokesman Streeting have vowed to extend the use of private companies for NHS services if Labour gets into government, while promising further austerity and refusing to say they will increase NHS funding to meet need, or increase wages for NHS staff, instead saying – just like Tories – that the NHS must ‘reform’ to be ‘sustainable’.

Both are also fully committed to the ‘Integrated Care’ programme of health rationing and incentivised cuts through withholding care – a direct import from disastrous US healthcare – that is wrecking the NHS even more thoroughly that previous Tory ‘reforms’.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

Wages and Inflation: Let Workers Alone

[Note: this is a slightly edited ChatGPT translation of an article for the Italian daily Domani]

Last week’s piece of news is the gap that opened between the US central bank, the Fed, and the European and British central banks. Apparently, the three institutions have adopted the same strategy, deciding to leave interest rates unchanged, in the face of falling inflation and a slowdown in the economy. But, for central banks, what you say is just as important as what you do; and while the Fed has announced that in the coming months (barring surprises, of course) it will begin to loosen the reins, reducing its interest rate, the Bank of England and the ECB have refused to announce cuts anytime soon.

To understand why the ECB remains hawkish, one can read the interview with the Financial Times of the governor of the Central Bank of Belgium, Pierre Wunsch, one of the hardliners within the ECB Council. Wunsch argues that, while inflation data is good (it is also worth noting that, as many have been saying for months, inflation continues to fall faster than forecasters expect), wage dynamics are a cause for concern. In the Eurozone, in fact, these rose by 5.3% in the third quarter of 2023, the highest pace in the last ten years. The Belgian Governor mentions the risk that this increase in wages will weigh on the costs of companies, inducing them to raise prices and triggering further wage demands; As long as wage growth is not under control, Wunsch concludes, the brakes must be kept on. Once again, the restrictive stance is justified by the risk of a price-wage spiral, that so far never materialized, despite having been evoked by the partisans of rate increases since 2021. Those who, like Wunsch, fear the wage-price spiral, cite the experience of the 1970s, when the wage surge had effectively fueled progressively out-of-control inflation. The comparison seems apt at first glance, given that in both cases it was an external shock (energy) that triggered the price increase. But, in fact, it was not necessary to wait for inflation to fall to understand that the risk of a wage-price spiral was overestimated and used by many as an instrument. Compared to the 1970s, in fact, many things have changed. I talk about this in detail in Oltre le Banche Centrali, recently published by Luiss University Press (in Italian): Automatic indexation mechanisms have been abolished, the bargaining power of trade unions has greatly diminished and, in general, the precarization of work has reduced the ability of workers to carry out their demands. For these and other reasons, the correlation between prices and wages has been greatly reduced over three decades.

But the 1970s are actually the exception, not the norm. A recent study by researchers at the International Monetary Fund looks at historical experience and shows that, in the past, inflationary flare-ups have generally been followed with a delay by wages. These tend to change more slowly than prices, so that an increase in inflation is not followed by an immediate adjustment in wages and initially there is a reduction in the real wage (the wage adjusted for the cost of living). When, in the medium term, wages finally catch up with prices, the real wage returns to the equilibrium level, aligned with productivity growth. If the same thing were to happen at this juncture, the IMF researchers believe, we should not only expect, but actually hope for nominal wage growth to continue to be strong for some time in the future, now that inflation has returned to reasonable levels: looking at the data published by Eurostat, we observe that for the eurozone, prices increased by 18.5% from the third quarter of 2020 to the third quarter of 2023, while wage growth stopped at 10.5%. Real wages, therefore, the measure of purchasing power, fell by 8.2%. Italy stands out: it has seen a similar evolution of prices (+18.9%), but an almost stagnation of wages (+5.8%), with the result that purchasing power has collapsed by 13%.

Things are worse than these numbers show. First, for convergence to be considered accomplished, real wages will have to increase beyond the 2021 levels. In countries where productivity has grown in recent years, the new equilibrium level of real wages will be higher. Second, even when wages have realigned with productivity growth, there will remain a gap to fill. During the current transition period, when real wages are below the equilibrium level, workers are enduring a loss of income that will not be compensated for (unless the real wage grows more than productivity for some time). From this point of view, therefore, it is important not only that the gap between prices and wages is closed, but that this happens as quickly as possible.

In short, contrary to what many (more or less in good faith) claim, the fact that at the moment wages are growing more than prices is not the beginning of a dangerous wage-price spiral and the indicator of a return of inflation; rather, it is the foreseeable second phase of a process of rebalancing that, as the IMF researchers point out, is not only normal but also necessary.

The conclusion deserves to be emphasized as clearly as possible: if the ECB or national governments tried to limit wage growth with restrictive policies, they would not only act against the interests of those who paid the highest price for the inflationary shock. But, in a self-defeating way, they would prevent the adjustment from being completed and delay putting once and for all the inflationary shock behind us.

Webbe says Hunt’s measures fatten the rich at poor’s expense – and Labour little better

Independent MP slams latest damaging Tory budget measures and assault on poor, sick and disabled

Leicester East MP Claudia Webbe has accused the Tory government of using Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement to fatten business at the expense of the poor, of ‘snatching the assessment of illness out of the hands of doctors’ to punish the long-term sick and of doing the exact opposite of what the UK economy needs – and says that Keir Starmer’s Labour is little better in enthusiastically promoting the discredited austerity narrative.

In a statement issued today, Ms Webbe said:

Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement boasted of giving corporations the biggest tax handout in modern British political history, doling out billions to companies – many of whom are already making obscene profits in a cost of greed emergency of soaring bills and food costs.

And he is doing this on the backs of the poor, sick and disabled, with horrendous measures to whip those who are unfit to work into taking jobs their medical experts have said they cannot do – and to do it they will snatch the assessment of illness out of the hands of doctors and have it decided by the government’s agents instead.

The past decade has seen a steep rise in poverty, with fourteen million people below the poverty line, including well over four million children. In Leicester East, four in every ten children were already living in absolute poverty – now the Chancellor says if people do not submit to his new regime to get them back into work, he will cut them off completely from support after six months. The effect of this on my constituents and the poor and sick across the country will be horrific.

This country, since 2010, has seen an appalling rise in the misery imposed on those who were already struggling to get by. More than four in ten disability benefit claimants have attempted suicide under the government’s brutal regime. Suicide has become the leading cause of death in men under fifty. Poor mental health abounds, yet the government has today shown it remains determined to punish and persecute those who cannot work – and indeed that it is determined to deny the reality of life in this country for so many.

In my constituency of Leicester East, we have seen endemic exploitation and poverty wages in our garment industry. I told the Chancellor in response to his Autumn Statement that the unionised manufacturing base of Leicester East has long been diminished – not replaced by technology, innovation and good modern jobs with decent pay, but by fast fashion, sweatshops and unscrupulous employers paying illegally-low wages. All this has been exploited by brands and retailers who are in a race to the bottom for ever-increasing profits while their supply chains fail to pay the minimum wage.

I asked him what action the government will take to regulate and ensure that brands and retailers are held to account for the sustainable outcomes of their products in their supply chains and wage justice for the people that make their goods, and to tackle those British brands and retailers who threaten to seek cheaper labour overseas so they can avoid paying the new minimum wage that the he had just announced. There was no meaningful response.

The government is using tweaks to the minimum wage – which it misnames the living wage – as cover for its handouts to business, but its increases are still very far below the level at which a person working one job could live on. The government claims work is the way out of poverty, but millions who are working are among the poorest.

Mr Hunt claims the government is going for growth, when in fact they are doing the exact opposite of what our economy needs – and hurting millions to do it. Economists recognise that the best way to boost economic growth is to give more money to the poor, because they have to spend it. But yet again the Conservatives are giving more to the rich and to corporations who will put much of it into offshore bank accounts where it does no good. As it is, despite his claims of growth he has had to acknowledge that the Office for Budget Responsibility is downgrading growth forecasts for the next three years.

And it has to be said that the Labour party is largely in agreement with the government it is supposed to oppose. This country needs politicians with the courage to speak the truth that the punishment of the poor to enrich the wealthy is a political choice and not a necessity or even productive. Sadly such politicians are at the moment in very short supply at the moment.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

Profits in a time of inflation: what do company accounts say in the UK and euro area?

Gabija Zemaityte and Danny Walker

Inflation has been high in many countries since 2021. Some have said that companies have increased their profits over that period: so-called ‘greedflation’. We use published company accounts for thousands of large listed companies to look for signs of increased profits in the data. Consistent with previous analysis of aggregate incomes, price indices and business surveys, we find no evidence of a rise in overall profits in the UK – prices have gone up alongside wages, salaries and other input costs. Companies in the euro area are in a similar position. However, companies in the oil, gas and mining sectors have bucked the trend, and there is lots of variation within sectors too – some companies have been much more profitable than others.

Recent analysis by Sophie Piton, Ivan Yotzov and Ed Manuel has shown that corporate profits have been relatively stable in the UK and that profits are unlikely to have been a big contributor to inflation. Others have suggested that the trend in the euro area has been somewhat different. In this post we use a novel data source to look at this question: the information companies have reported in their accounts.

Company accounts provide a window into how profits have evolved

Large companies that are listed on the stock market publish company accounts at regular intervals, which give a summary of their operating performance. We use a sample of more than 1,000 companies per year – based on accounts that are currently available up to the end of 2022 – to analyse how profits have evolved during the high-inflation period.

Why look at large companies? They play a major role in the UK economy – they account for 40% of total employment and almost half of total turnover. There is also evidence that they have more market power than smaller companies, so are more likely to be able to increase profits.

We compute the ratio of profits to value added for all non-financial listed companies in the UK and the euro area. The profit measure we use is earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), which is a standard accounting measure. Value added is defined as EBIT plus total wage and salary costs at the company level. This measure naturally avoids some of the issues that distort the national accounting data, such as the inclusion of non-market income, tax and self-employment or mixed income.

We compare the UK to the euro area, where companies have faced similar shocks over the last few years, including the Covid lockdowns and recovery, the rise in global supply-chain pressures and the surge in European energy and other raw material prices.

There is no evidence of a significant rise in the profit share on aggregate in the UK or euro area

The profit share has increased only moderately since Covid in the UK and euro area (we focus here on companies in Germany, France, Italy and Spain). It has remained broadly in line with its long-term trend since the early 2000s (Chart 1).

How has the profit share been so stable? Profits have increased significantly in nominal terms in the UK and euro area, by somewhat more in the UK than in the euro area. But this increase in profits has been accompanied by sharp increases in inputs costs. Indeed, total costs – defined as the sum of the cost of goods sold, wages and salaries – has increased by around 60% in the Euro area since 2020, and around 80% in the UK.

The level of the profit share reflects the set of companies captured in the sample, which tend to be larger, more profitable and more capital-intensive than the average in the economy as a whole – and the oil and gas sector is over-represented. These compositional issues mean we should focus on analysing changes in the UK or euro area over time, rather than differences between the two. But it is notable that in aggregate, the profit share has been broadly stable even when excluding oil, gas and mining sectors.

Chart 1: Profit share in UK and euro area based on company accounts

Notes: Sum of total profits (EBIT) as a ratio to value added (EBIT plus wages and salaries) across all non-financial listed companies in each region. Dotted line is a linear trend. Euro area includes non-financial companies in Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

The oil, gas and mining sectors have seen a large increase in profits in the UK and euro area

Chart 2 compares the profit shares in 2022 to those in 2021 at sectoral level, for the UK and the euro area in turn.

Most sectors have had very little change in profit shares in the UK. But three sectors have seen an increase in profit share that is larger than 5 percentage points. Those sectors are oil, gas and mining; utilities; and other services (which includes industries such as gambling and leisure facilities). Together they make up around 7% of total output in the economy.

The euro area has had stable profit shares for most sectors too. The sectors that have seen an increase in profit share that is larger than 5 percentage points are oil, gas and mining, professional services and construction. Those sectors account for around 12% of total output in the economy.

Chart 2: Profit share in UK and euro area by sector

UK companies

Euro area companies

Notes: Average profits (EBIT) as a ratio to value added (EBIT plus wages and salaries) in 2021 and 2022 across all non-financial listed companies. Excludes companies with negative profits. Bubble size is proportional to sectoral gross value added in the national accounts. Solid line is the 45 degree line – sectors on the line have had a constant profit share.

Every sector includes companies that have done much better than others

While only a few sectors have seen a significant increase in profit shares, there is lots of variation within sectors. The newspapers are full of stories about individual companies that have done well. Chart 3 shows the share of revenue within each sector accounted for by companies that have seen an increase in their profit share of at least 5 percentage points.

In the UK, the sectors with the highest share of companies with large increases in profit share are other services (88%), oil, gas and mining (66%) and utilities (43%), which is unsurprising given those sectors did well on aggregate. But all of the other sectors contain companies that have seen large increases in profit shares. The smallest share is in the construction sector, where less than 2% of companies have seen a large increase in profits.

In the euro area, on the other hand, the top three sectors with the highest share of companies with large increases in profit share are oil, gas and mining (52%), transport (45%) and wholesale trade (43%). Other than oil, gas and mining, this paints a different picture to the aggregate results, which means that those results are driven by a few large companies. Consistent with the UK results, all sectors contain companies that have seen large increases.

Chart 3: Share of companies reporting more than a 5 percentage point increase in profit share from 2021 to 2022 by sector

Notes: The chart shows the proportion of companies in each sector and region – weighted by total revenue – where aggregate profits (EBIT) as a ratio to value added (EBIT plus wages and salaries) rose by 5 percentage points or more from 2021 to 2022. Sample is all non-financial listed companies. In the euro area it includes companies in Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

Summing up

This post uses a large sample of listed UK and euro-area companies to test for the existence of ‘greedflation’. Consistent with other sources, it doesn’t look like the corporate sector as a whole has seen an abnormally large increase in profits during the period of high inflation. That is because wages, salaries and other input costs have gone up by just as much as profits. The oil, gas and mining sector consistently bucks the trend, which is unsurprising. And there are of course many examples of individual companies in all sectors that have been particularly profitable.

Gabija Zemaityte works in the Bank’s Macro-financial Risks Division and Danny Walker works in the Bank’s Deputy Governor’s office.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.