reading

Sunday, 10 April 2016 - 6:20pm

This week, I have been mostly researching for an essay, but when feeling naughty I've been reading:

- Why Some Students Are Ditching America for Medical School in Cuba — Sarah Zhang in WIRED:

Consider Cuba’s medical system, which punches far above its weight. The country’s GDP per is just one-tenth of the US’s, and it lacks access to drugs and equipment thanks to the US trade embargo. But life expectancy in Cuba is actually just above that of its northern neighbor. How? By focusing on preventive medicine for everyone under a national healthcare system.

- How Gates' Billions Silences Criticism of His Development Agenda — Nick Dearden, Common Dreams:

Initiatives that Gates funds push intensive farming methods involving plenty of chemicals and privatisation of seed distribution. Time and again, these ‘solutions’ have proved disastrous for small farmers, allowing big players to effectively control the whole food system. They also ramp up global carbon emissions and fuel global warming. But they are exactly what big business wants. In fact, Gates aid sometimes looks designed to help agribusiness develop new markets – like a project with agro-giant Cargill which helped it develop soya ‘value chains’ in Africa. It’s not a conspiracy, it’s simply how Gates, like so many of his fellow plutocrats, believe the world works. Big business invents useful stuff and drive growth. Let’s help them and everyone will be better off.

- The Mythology of Selfishness — Mary Midgley in The Philosophers Magazine:

Our own thoughts and feelings – the constant flow of inner activity by which we respond to the life around us – also affect the world as well as our outward actions. This thought is so frightening that scholars will often go to any lengths to avoid it, which is why that ludicrous doctrine epiphenomenalism still has supporters, and why people spend so much more of their time on sociological statistics, neurological details and speculation about evolutionary function than on studying motive.

- The Death of Capitalism — Ian Welsh:

If you were 30 in 1980, you are 66 today. If you were 40, you are 76. If you were in the decision making class, overwhelmingly allocated to those who were 50+ in 1980, you are 86 today. People who were in their prime and during their decision-making days, when we needed to act on climate change, were making a DEATH BET. They bet they would be dead before the worst results of climate change happened. They will win this bet. This was a RATIONAL thing for them to do. I want to repeat that, because too many people think “rational=good.” It does not. It was rational for them to discount a future they would not see.

Also, What Is Capitalism?:The responses to my article The Death of Capitalism made something clear: Most people don’t know what Capitalism is.

[The argument is a thoughtful one, but I have a simpler definition: Capitalism is a doctrine which frames all human activity in terms of investment and return.] - The Volcanic Core Fueling the 2016 Election — Robert Reich:

I’ve known Hillary Clinton since she was 19 years old, and have nothing but respect for her. In my view, she’s the most qualified candidate for president of the political system we now have. But Bernie Sanders is the most qualified candidate to create the political system we should have, because he’s leading a political movement for change.

- Consumer credit and mortgage finance in the 1920s — Matias Vernengo at Naked Keynesianism:

The Great Depression put an end to the roaring 20s. The unsustainable expansion of consumer credit and mortgages seems to have played, as much as in the last crisis, a significant role.

- How Long Will Your Class Remain Yours? Academic Freedom and Control of the Classroom — Jonathan Rees in Hybrid Pedagogy:

An LMS not only mediates and records all interactions between teachers and students in both the online classes and face-to-face classes that utilize it, but it also represents a teaching worldview all by itself. As Jim Groom and Brian Lamb explain, “[B]efore we even begin to encounter the software itself, we privilege a mindset that views learning not as a life-affirming adventure but instead as a technological problem, one that requires a ‘system’ to ‘manage’ it. This mindset and its resulting values result in online architectures that prioritize user management, rigidly defined and restricted user roles, automated assessments, and hierarchical, topdown administration.” Trying to control your own virtual classroom in this environment is like bringing a knife to a gunfight. You know you’re going to lose before the fighting starts, so why bother?

And from the linkage therein: - Critical Pedagogy in the Age of Learning Management (#moocmooc) — by Sean Michael Morris, who ordinarily would have lost me at the word "critical":

The advent of online learning has introduced a new level of data and measurement (also, fucking absurdity) into education. With the learning management system (LMS) comes the ability to track all kinds of information about student performance, participation, and more. At the LMS company where I worked until recently, educational research often focused on the activity of learners on pages, watching videos, taking and passing quizzes, participating in or starting discussions in the forum, and other minutiae. It’s possible to track time on page, time in the course, and the “bounce rate” for learners in their courses. In effect, the research being done isn’t about learning, it’s about surveillance, about observing the learner in the way we might a rat in a maze.

Sunday, 3 April 2016 - 8:36pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Why should Bill Gates get to set the agenda for international development? — Polly Jones, Global Justice Now:

Our new report Gated Development demonstrates that the trend to involve business in addressing poverty and inequality is central to the priorities and funding of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This is far from a neutral charitable strategy, but instead an ideological commitment to promote neoliberal economic policies and corporate globalisation. Big business is directly benefitting, in particular in the fields of agriculture and health, as a result of the foundation’s activities, despite evidence to show that business solutions are not the most effective.

[A philanthropist gives to charity. A philanthrocapitalist becomes a charity.] - The Seven Stages of Establishment Backlash: Corbyn/Sanders Edition — Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept:

[T]he nature of “establishments” is that they cling desperately to power, and will attack anyone who defies or challenges that power with unrestrained fervor. That’s what we saw in the U.K. with the emergence of Corbyn, and what we’re seeing now with the threat posed by Sanders. It’s not surprising that the attacks in both cases are similar — the dynamic of establishment prerogative is the same — but it’s nonetheless striking how identical is the script used in both cases.

- Who Pays Writers? — Maggie Doherty in Dissent Magazine:

Artistic experimentation depends on the material security that the welfare state provides. It’s easier to be avant-garde when you’re not wondering about the source of your next paycheck or worrying about prospective book sales. In the words of one grant recipient, responding anonymously to an NEA survey from the 1970s, federal grants offer writers “temporary freedom from a stultifying and paralyzing form of economic bondage.” For writers, economic freedom is tantamount to artistic freedom. The NEA redistributed such freedoms by funding writers who weren’t lucky enough to call financial security a birthright.

- Good news everyone! We've moved on from retrospectively blaming Greece for the GFC to retrospectively blaming China! Don’t blame China for these global economic jitters — Ha-Joon Chang in The Guardian:

[T]he main causes of the current economic turmoil lie firmly in the rich nations – especially in the finance-driven US and UK. Having refused to fundamentally restructure their economies after 2008, the only way they could generate any sort of recovery was with another set of asset bubbles. Their governments and financial sectors talked up anaemic recovery as an impressive comeback, propagating the myth that huge bubbles are a measure of economic health.

- Who are the spongers now? — Stefan Collini, London Review of Books:

It is the application of [the neoliberal] model to universities that produces the curious spectacle of a right-wing government championing students. Traditionally, of course, students have been understood by such governments, at least from the 1960s onwards, as part of the problem. They ‘sponged off’ society when they weren’t ‘disrupting’ it. But now, students have come to be regarded as a disruptive force in a different sense, the shock-troops of market forces, storming those bastions of pre-commercial values, the universities. If students will set aside vague, old-fashioned notions of getting an education, and focus instead on finding the least expensive course that will get them the highest-paying job, then the government wants them to know that it will go to bat for them.

Sunday, 27 March 2016 - 1:59pm

This week, I have been mostly going to pieces, so only reading this much:

- The Optimism Error — Robert Skidelsky proposes a British Investment Bank to fend off hysteresis:

So we now have a situation in which the main tools available to government to bring about a robust recovery are out of action. In addition, sole reliance on monetary policy for stimulus creates a highly unbalanced recovery. The money the government pours into the economy either sits idle or simply pumps up house prices, threatening to re-create the asset bubble that produced the crisis in the first place. We already have the highest rate of post-crash increase in house prices of all OECD countries. This suggests that the next crash may not be far off.

[Though I disagree vehemently with the view that "printing money to pay for public spending should only be a remedy of the last resort". Money creation through central-bank-funded fiscal deficits should be the norm for any government that does not want to hand responsibility for money supply to commercial banks, who are responsible for channeling money into the very bubbles Skidelsky is worried about.] - Australian copyright reform stuck in an infinite loop — Kathy Bowrey in The Conversation:

For example, section 113M allows libraries and archives to make “preservation copies” of original material that is of historical or cultural significance to Australia, but they are not allowed to make these copies available to patrons except through a terminal on site. As a researcher I am not allowed to make an electronic copy of the material so I can use it in writing up my research. As is common practice in libraries I would probably be allowed to transcribe a document by hand. However transcribing by hand is, as a matter by law, no different to a digital reproduction. Why does this law require me to spend public research money to physically attend the institution, perhaps also requiring an airfare and accommodation expenses, so I can take out my quill?

- Paul Krugman, Bernie Sanders, and Medicare for All — Dean Baker, CEPR via Econospeak:

Ordinarily economists treat it as an absolute article of faith that we want all goods and services to sell at their marginal cost without interference from the government, like a trade tariff or quota. However in the case of prescription drugs, economists seem content to ignore the patent monopolies granted to the industry, which allow it to charge prices that are often ten or even a hundred times the free market price. (The hepatitis C drug Sovaldi has a list price in the United States of $84,000. High quality generic versions are available in India for a few hundred dollars per treatment.) In this case, we are effectively looking at a tariff that is not the 10-20 percent that we might see in trade policy, but rather 1,000 percent or even 10,000 percent.

- SWEET HOLY F---!!!! — exclaims Brad DeLong:

- Neoliberalism, public and private goods and the digital revolution: Part one — Nicholas Gruen at Club Troppo:

[…] if knowledge and digital artefacts are always and everywhere a potential public good, you’d expect that expressing the collective interest in that fact would lead to a role for collective institutions (not necessarily government) representing the public interest as a countervailing force against private interests. As Robert Kuttner argues, an identifying idea of progressives since the turn of the 20th century if not before that capital needs a counterweight – in the state and other collective institutions. An obvious agenda is IP, which is becoming progressively more unbalanced towards the interests of private IP holders (Will Mickey ever go free?). Likewise arrangements for the creation of knowledge about drugs is a big mess, incredibly poorly suited to the interests of lower income countries but also to economic efficiency more broadly.

- The Citadel Is Breached: Congress Taps the Fed for Infrastructure Funding — Ellen Brown:

Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon), ranking member on the House Transportation Committee, retorted [to Ben Bernanke], “For the Federal Reserve to be saying [deficit spending] impinges upon their integrity, etc., etc. — you know, it’s absurd. This is a body that creates money out of nothing. [I]f the Fed can bail out the banks and give them preferred interest rates, they can do something for the greater economy and for average Americans.”

- The Remarkable Bernie Sanders Journey That Will Overcome the Crowning of Clinton — RoseAnn DeMoro of National Nurses United at Common Dreams:

Enthusiasm for the Sanders campaign, the transformative program that he presents, which is really the program NNU and grassroots activists have long championed, is off the charts, and continuing to grow.

Sunday, 20 March 2016 - 4:25pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

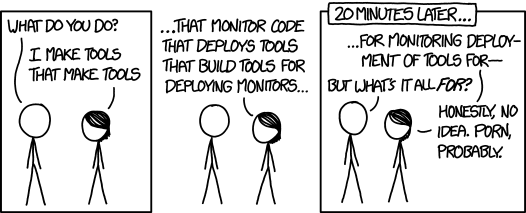

- Tools — xkcd:

- Impossible possibilities for Keynes’s grandchildren — David F. Ruccio:

[W]hat Keynes did not understand is that workers don’t just produce wealth, which they can then enjoy by reducing the amount of work they do. They produce wealth that stands opposed to them, wealth in the form of capital, which is then used to render part of the working population superfluous, thus dragging down the wages of other workers, who are then employed to boost the profits of their employers. The workweek of the employed population doesn’t decrease, even as they are joined to new technologies and are transferred to new sectors of the economy.

- Shortly after her death, Harper Lee's heirs kill cheap paperback edition of To Kill a Mockingbird — Cory Doctorow, Boing Boing:

A court upheld the sealing away of Lee's will from public view, so it's impossible to say for sure what prompted the move, but this much is clear: schools that assign "To Kill a Mockingbird" -- one of the most commonly assigned books in US classrooms -- will have to pay a lot more for their books, and that money will not, and cannot, benefit the author.

- The Story of Our Economy in 2015: A cocktail of household consumption, household consumption, and more household consumption — Frank Van Lerven at Positive Money:

The OBR forecasts that real GDP growth will average 2.3-2.5% a year between 2016 and 2020. This growth is meant to take place despite the reduction in government expenditure. As we have suggested before, considering that the UK is not a net exporter, if the government decides to reduce its level of debt then the domestic private sector has to take on more debt for there to be any growth. Increasing levels of private sector debt, (business and household borrowing), will be called upon to drive growth in the years to come.

- The co-option of government by transnational organisations — Bill Mitchell:

The process of privatisation clearly transferred resources from the public sector to the private sector and reduced the public bureaucratic control of the organisations in question. Those processes are reversible. If we want a demonstration of that reversibility, then we need not look further than what happened to the banking sector in the early days of the GFC when many national governments effectively socialised the losses from the failed corporate strategies, protected depositors and nationalised the organisations. There was no hint then that the nation-state had lost its power or discretion to act to advance the national interest and largely disregard the interests of the private shareholders of these large transnational, financial entities.

- Despair Fatigue — David Graeber in The Baffler:

True, most mainstream economists are capable of seeing through obvious nonsense, like the justifications proposed for fiscal austerity. But the discipline is still trying to solve what is essentially a nineteenth-century problem: how to allocate scarce resources in such a way as to optimize productivity to meet rising consumer demand. Twenty-first century problems are likely to be entirely different: How, in a world of potentially skyrocketing productivity and decreasing demand for labor, will it be possible to maintain equitable distribution without at the same time destroying the earth? Might the United Kingdom become a pioneer for such a new economic dispensation?

- A thought experiment for Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull — Steve Keen in Business Spectator:

Imagine that there is an economy where the money supply consists of a single dollar, which is exchanged 100 times per year among this economy’s inhabitants — thus generating a GDP of $100 per year. Then imagine that the government in this economy sets itself the target of running a surplus equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP. If the government achieves its objective, what will GDP be the following year? Zero. And, if the government debt ratio was more than 1 per cent beforehand, it will be infinite afterwards. Why? Because the economy had only one dollar of money in existence, and the government’s surplus took that $1 out of circulation, leaving the economy with precisely zero dollars for commerce the following year. The government budget affects GDP by changing the amount of money in circulation in the economy, and a government surplus effectively destroys money.

- Are luxury condo purchases hiding dirty money? — Husna Haq at the Christian Science Monitor:

In fact, using shell companies, or limited liability companies, to hide a buyer's identity is actually relatively common, and legal. But the practice could drive up real estate prices in some markets, and contribute to real estate booms. Federal authorities are also concerned that the practice enables foreign buyers to easily find a safe haven for illicit money in American real estate.

- How does the 1 percent capture the surplus? — David Ruccio:

The basic idea is that “pass-throughs”—businesses whose annual income is taxed at the owner-level (such as partnerships and S-corporations)—now account for more than half of all U.S. business income, thus passing traditional (so-called C) corporations. […] 54.2 percent of U.S. business income in 2011 was earned in the pass-through sectors, compared to only 20.7 percent in 1980.

- "Neoliberalism" is it? — Jeremy Fox takes on Will Davies' challenge of a week earlier in openDemocracy:

Compared with some other candidates, ‘neoliberalism’ does not seem to be an especially elusive abstraction. I take it to mean marketisation of the public realm as a political project. Its current popularity among political leaders of a certain hue is that it has the appearance of offering value-free decision-making because it allows market competition rather than ideological bias to determine value. They are thereby absolved, at least in theory, from responsibility for the provision of important public services.

- Why you shouldn’t let your smartphone be the boss of you — Peter Fleming in the Guardian:

According to an influential group of neoliberal economists working in the 1970s, people ought to see themselves as “human capital” rather than human beings. This sort of capital is a never-ending investment, continuously enhanced in relation to skills, attitude and even physical appearance. Work is crucial for building this capital, perhaps its defining source. This is where employment and life more generally slowly merge and become indistinguishable from each other. A job is no longer something we do to achieve socially productive goals in society. An activity among other pursuits. No, a job today is something we are … preferably 24/7. Working unpaid overtime therefore seems natural. Self-exploitation looks like personal freedom.

- The return of public investment — Dani Rodrik:

If one looks at the countries that, despite strengthening global economic headwinds, are still growing very rapidly, one will find public investment is doing a lot of the work.

- Diane Coyle finds Minsky, but misses Keynes — Geoff Tily, Prime Economics:

Now Keynes was no trivial figure. How can it not be “interesting” that one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century was misrepresented by the academic economics profession, and this misrepresentation has been denied ever since? How can what he actually said not be interesting, once we recognise that what we thought he said was wrong? How can his work not be interesting if it treats finance and the shortcoming of conventional macroeconomics is that it doesn’t treat finance?

- Ultra-Rich 'Philanthrocapitalist' Class Undermining Global Democracy: Report — Sarah Lazare at Common Dreams:

A study just out from the Global Policy Forum, an international watchdog group, makes the case that powerful philanthropic foundations—under the control of wealthy individuals—are actively undermining governments and inappropriately setting the agenda for international bodies like the United Nations. The top 27 largest foundations together possess assets of over $360 billion, notes the study, authored by Jens Martens and Karolin Seitz. Nineteen of those foundations are based in the United States and, across the board, they are expanding their influence over the global south. And in so doing, they are undermining democracy and local sovereignty.

- 5 outrageous things educators can’t do because of copyright — Lisette Kalshoven in Medium:

The current patchwork of copyright exceptions for education at the member state level can lead to absurd situations for teachers that want to utilize creative works. We asked friends from across Europe to submit examples showing where copyright and education do not mix. You can cry (or laugh) with us.

Sunday, 13 March 2016 - 5:11pm

This week, (actually posted a day late, but back-dated) I have been mostly reading:

- Older Students Learn for the Sake of Learning — Harriet Edleson at the "Well, d'uh!" desk of the New York Times:

For lifelong learners the focus is outward. At Osher, classes are not specifically skill-based, like learning a language or weaving. Instead, students generally delve into subjects they may have been interested in for years but simply didn’t have time to study.

- Report From the Student Privacy Frontlines: 2015 in Review — Annelyse Gelman, Electronic Frontier Foundation:

This year the fight to protect student privacy hit a boiling point with our Spying on Students campaign, an effort to help students, parents, teachers, and school administrators learn more about the privacy issues surrounding school-issued devices and cloud services. We're also working to push vendors like Google to put students and their parents back in control of students’ private information.

- Japanification Revisited — Ian Welsh:

In choosing the method we chose to do the bailouts, we also made the choice to have a shitty economy. Employment has never recovered, in terms of the percentage of the population, and will not (we’re about to hit a recession), wages are down for much of the population, and all the gains of the last economic cycle have gone to the top three to five percent. Mind you, there was an historic stock bubble. The rich are even richer than they were in 2007. Obama and Bernanke’s policy has done what it was intended to: It has preserved, and then increased, the wealth of the rich.

- The corporate university and its threat to academic freedom — Sean Phelan in openDemocracy:

It would be simplistic to suggest that the corporate university represents an ideological vision spontaneously brought into being by a managerial class. As recent changes to the governance of New Zealand university councils – rescinding the guaranteed representation of both students and staff – suggests, the desire for a corporate university is often a state-led political project, pushed by governments who want to reduce public funding to universities, and reconfigure the university as little more than an engine of economic growth.

- Neoliberalism and its forgotten alternative — David Ridley, openDemocracy:

Sociologists and social scientists need to be a part of an active process of giving back social inquiry to the public, emancipating this deeply human and social activity first and foremost from the elitism, specialisation and instrumentalism of academia. We may need to reduce the working week even further to enable people to have time for community activities and public research. We certainly need to prevent education from being turned towards a class-based, narrowly vocational process of training people to be profit-making machines.

- Because you can never have too many charts on the economics of credit cards — Harold Pollack in The Reality-Based Community:

[P]rofit margins are really high for the small group of borrowers with low FICO scores in the range of about 550. Amazingly, the industry made about $0 in cumulative profits on the top 80% of accounts that have FICO scores exceeding 630. The bottom 10% of accounts account for the majority of total industry profits. It’s also striking that the industry actually seems to lose money on consumers near the median of the distribution with FICO scores around 700, and then makes profit again on the best credit risks.

- Why Minsky Matters: An Introduction to the Work of a Maverick Economist — Victoria Bateman reviews Randy Wray's new book about the work of his mentor:

As 2008 so clearly showed, we simply cannot have our cake and eat it. Financial crises are not just events that happened a long time ago in history – or far, far away in distant and much poorer lands. They are hard-wired into the capitalist system. Minsky was one of the valiant few who tried to draw attention to this fact, and one of the few to predict the global financial crisis decades before it actually hit. Unfortunately, his warnings fell on deaf ears. Like many a great artist, his popularity soared only after his death and only once the crisis hit – in what came to be known as a “Minsky moment”.

- #ResistCapitalism — Cameron K. Murray:

[S]ome kind of welfare state is essential for maintaining the dynamism of the capitalist part of the economy. Without this cushion against failure, who would risk their life savings on inventing and investing in new products and innovations? Essentially we all want a mixed economy, a level of safety net that reflects the wealth of the country, and basic services provided in an equitable manner. […] But when the political power of a select few capitalists overwhelms the system to the extent that the other non-capitalist parts of the mixed economic suffer, there are obvious and genuinely satisfying moral grounds for protest.

- Facebook is no charity, and the ‘free’ in Free Basics comes at a price — Mark Graham in The Conversation isn't keen on Zuckerberg's reboot of Compuserve:

In much the same way that Nestlé offered free baby formula in the 1970s as development assistance to low-income countries – leaving nursing mothers unable to produce sufficient milk themselves – Free Basics is likely to impede commercial alternatives.

- The Procrustean Economy — Neil Wilson:

The data collected from [neoliberal] economies will resemble the data you would expect from the [neoliberal] model. It really can't do much else - since the policies are there to prevent deviation from the norm. Therefore when you do empirical studies what you are actually using as data is the output from a system rammed into an inappropriate model. The data is tainted and what the taint means has to be understood.

- The Fed Doesn’t Work For You — J. W. Mason in Jacobin:

A rising wage share supposedly indicates an overheating economy — a macroeconomic problem that requires a central bank response. But a falling wage share is the result of deep structural forces — unrelated to aggregate demand and certainly not something with which the central bank should be concerned. An increasing wage share is viewed by elites as a sign that policy is too loose, but no one ever blames a declining wage share on policy that is too tight. Instead we’re told it’s the result of technological change, Chinese competition, etc. Logically, central bankers shouldn’t be able to have it both ways. In practice they can and do.

- Globalisation and currency arrangements — Bill Mitchell:

The thesis advanced by many analysts is that globalisation has reduced the capacity of the nation-state and forced governments to adopt free market policies at the microeconomic level and austerity at the macroeconomic level, for fear that capital flight will destroy their economies. It is a neatly packaged thesis that the political Left has imbibed, and, in doing so, has undermined the progressive basis of these institutions and left voters with little choice between right-wing parties and the social democratic parties who formally represented the interests of workers and acted as mediators in the class conflict between labour and capital. The major distinguishing feature these days between these two types of parties, who were previously poles apart in approach and mandate sought, is that the so-called progressive side of politics now claims it will implement austerity in a fairer way. These austerity-lite parties, buying into the myth that globalisation has undermined the capacity of the state to pursue full employment policies with equitable income distribution, do not challenge the basis of austerity, but just quibble over who should pay for it.

- In 2016, let's hope for better trade agreements - and the death of TPP — Joe Stiglitz via the Guardian:

In place of global trade talks, the US and Europe have mounted a divide-and-conquer strategy, based on overlapping trade blocs and agreements. As a result, what was intended to be a global free trade regime has given way to a discordant managed trade regime. Trade for much of the Pacific and Atlantic regions will be governed by agreements, thousands of pages in length and replete with complex rules of origin that contradict basic principles of efficiency and the free flow of goods. […] Obama has sought to perpetuate business as usual, whereby the rules governing global trade and investment are written by US corporations for US corporations. This should be unacceptable to anyone committed to democratic principles.

- ObamaCare’s Neoliberal Intellectual Foundations Continue to Crumble — Lambert Strether via Naked Capitalism:

Obama gives an operational definition of a functioning [health insurance] market that assumes two things: (1) That health insurance, as a product, is like flat-screen TVs, and (2) as when buying flat-screen TVs, people will comparison shop for health insurance, and that will drive health insurers to compete to satisfy them. As it turns out, scholars have been studying both assumptions, and both assumptions are false. […] the population studied reduces costs, not by comparison shopping, but by self-denial of care. […] it looks like ObamaCare has replaced a system where insurance companies deny people needed care with a system where people deny themselves needed care; which is genius, in a way.

- Mainstream macro and Minsky the maverick — Diane Coyle reviews, perhaps too briefly, Randy Wray's new book:

The second chapter was to me the most interesting. It’s called ‘The Road Not taken’ and sets out the broad mainstream approach against which Minsky developed his arguments. This is the neoclassical synthesis, whose foundations were laid by John Hicks and Alvin ‘Secular Stagnation’ Hansen in the early years after Keynes’s death, then by both ‘Keynesians’ like Patinkin and Tobin and ‘Monetarists’ such as Friedman. Wray argues that these camps disagreed largely over parameter values, and that they essentially bowdlerised Keynes by ignoring his emphasis on investment, finance and uncertainty.

[I admit to some satisfaction, bordering on relief, at finding somebody confirming that new Keynesians and neoliberals "disagreed largely over parameter values", having just this morning confidently asserted on a uni discussion board that there has long been "broad agreement within mainstream economics over what the appropriate policy levers are, but disagreement about where these levers should be set".]

Sunday, 6 March 2016 - 5:38pm

This week, I have been mostly driving between home and the hospital as my dear lady wife waited (and waited, and waited…) for surgery, so the few most interesting things I've read are:

- Intellectual property and the decline of the U.S. labor share — Nick Bunker, Wahington Center for Equitable Growth:

According to the paper, the decline [in the US labor share] starts in 1947, which would mean the labor share was declining throughout the period it was famously stated to be constant. But not only does the decline start earlier than previously thought—it’s also much larger. It’s actually twice as large. And the increase in intellectual property products explains the entirety of the decline.

- George Obsorne says its austerity, whether it busts us or not — Richard Murphy:

At the precise moment when the economy needs investment more than anything else, in flood defences and onwards, and at a time when we do as a nation not only have the capacity to deliver that investment because there is a shortfall in demand for other goods and services, but also have the means to fund that investment because borrowing costs are, for the government, little above zero per cent in real terms right now, George Osborne is saying he will not make any effort to help the UK economy by undertaking that essential investment programme. He is instead saying that when demand is weak he will make it weaker. And that when investment is needed he will not undertake it.

- The mass consumption era and the rise of neo-liberalism — Bill Mitchell:

The research I have been doing in the last few days continues the theme that globalisation has not rendered the nation state impotent. The thesis, as outlined in the introduction, is that the nation state has just changed its role and now uses its power to advance more narrow interests than previously.

- The Best Paid People in Our Societies Are the Worst People — Ian Welsh:

Private bankers and financial execs make almost all of the investment decisions in our society. They decide what will be built, what jobs will be created, etc. They are the people who decide if something will happen and they make terrible decisions–even based on their own valuation system. […] Do not speak of “salary” and “merit” in the same sentence except with scorn. When the CEO doesn’t show up, so what? When the janitor doesn’t show up, though, hey! We find out who really matters.

- Who Are The Prominent Academics Who Advocate A Different Type of QE? — Frank Van Lerven, Positive Money:

In a recent post Positive Money showed that there is a strong intellectual body of history behind the various alternative proposals for QE. Both John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman proposed a style of Quantitative Easing (QE) that was aimed at the real economy. Today, these types of proposals are commonly referred to as “QE for People”, “Sovereign Money Creation”, “Strategic QE” and “Helicopter Money” amongst others.

Sunday, 28 February 2016 - 8:35am

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Helicopters already exist. If you know where to look — Neil Wilson braves the slippery slope from advocating for central bank independence to…:

And then you move onto the question of war. If parliament can't be trusted with money, or social security, why should it be trusted in sending people to their deaths. […] Of course if the generals are in charge and are able to deploy troops independently of parliament, then we would rightly call that a military dictatorship. Therefore the notion of an independent central bank should be called out for what it is - an economic dictatorship ruled over by a class of individuals who look after the interests of the bankers and creditors and want to prevent government having first access to the resources of the country. Those supporting the idea are excuse makers for that destructive regime.

- The difficulty of ‘neoliberalism’ — Will Davies, Political Economy Research Centre:

The reason ‘neoliberalism’ appears to defy easy definition (especially to those with an orthodox training in economics or policy science) is that it refers to a necessarily interdisciplinary, colonising process. It is not about the use of markets or competition to solve narrowly economic problems, but about extending them to address fundamental problems of modernity – a sociological concept if ever there was one. For the same reasons, it remains endlessly incomplete, pushing the boundaries of economic rationality into more and more new territories. […] The dramatic rise of student indebtedness in the UK makes little economic sense for anyone (even the government) but it succeeds in placing higher education in a quantitative framework, linking past, present and future.

- Keywords for the Age of Austerity 24: Sullen — John Patrick Leary:

The problem is not just that education is vocational here, because there’s nothing wrong with vocational education per se, nor is “critical thinking” or moral education or whatever you want to call it necessarily un-vocational anyway. Rather, it is the way “academic entrepreneurship” encourages students and others to see education, a public service subsidized to great extent by the people, as a publicly-funded adjunct of private business, useful for research, development, and employee training. Lesson number 1 of entrepreneurship class: Why take a financial risk when you can just outsource it to someone else?

- The Great Malaise Continues — Joseph Stiglitz:

The obstacles the global economy faces are not rooted in economics, but in politics and ideology. The private sector created the inequality and environmental degradation with which we must now reckon. Markets won’t be able to solve these and other critical problems that they have created, or restore prosperity, on their own. Active government policies are needed. That means overcoming deficit fetishism.

- New Research. Inequality of Wealth Makes Us Short and Dead — Peter Turchin in Evonomics:

So, the life expectancy of white middle-aged males has declined, and the average height of black women has also declined. Is this the beginning of a more broadly based trend, in which the biological well-being of the “other half”—the 50 percent of the poorer Americans—will decline?

- ‘Helicopter tax credits’ to accelerate economic recovery in Italy (and other Eurozone countries) — Biagio Bossone and Marco Cattaneo at VoxEU.org:

Tax Credit Certificates (TCCs) […] are assigned to households in inverse proportion to their income, both for social equity purposes and to incentivise consumption. TCC allocations to enterprises are proportional to their labour costs, and act as labour-cost cutting devices, immediately improving their competitiveness, as any internal or external devaluation would do. Greater export and import substitution following price reductions not only create more output and employment, they also offset the impact of increased demand on the external trade balance. Smaller amounts of TCCs can also be issued and used by the government to pay for public infrastructure initiatives and social welfare programs.

- The DWP is trying to psychologically 'reprogramme' the unemployed, study finds — Jon Stone, The Independent:

A study backed by the Wellcome Trust found that people without jobs were subject to humiliating “reprogramming” by authorities designed to change their mental states. The researchers said the new approach, which forced upon the unemployed a “requirement to demonstrate certain attitudes or attributes in order to receive benefits or other support, notably food” raised major ethical issues.

- Economists Don't Know Much About the Economy, #46,523: The Story of the Robots — Dean Baker in HuffPostBiz:

Patent and copyright protection are not laws of nature, they come from the government. And in recent years we have been making them stronger and longer. […] In the absence of these protections, we might all look forward to paying a few dollars for the robots that will clean our houses, cook our food, and drive us wherever we want to go. Low cost robots would make almost all of us richer. Only if the government imposes patent monopolies that keep robots expensive do we have to worry about a redistribution from the rest of us to those who "own" the technology.

- Huge currency zones don’t work – we need one per city — Mark Griffith in Aeon:

In the 1970s, the American/Canadian economist Jane Jacobs reached a radically simple insight. Her lifelong interest in urban history convinced her that cities, not countries, drive economics. Cities are messy, unplanned places where people who otherwise would never meet devise joint projects. Hence, Jacobs argued, all innovation happens in cities. It made sense, then, that each city’s currency should follow its business cycle. Forcing two or more cities to share one currency slowly pumps up one city and sickens the others.

- Designer nights out: good urban planning can reduce drunken violence — Kees Dorst in The Conversation:

It is easier said than done, but we need to think away from knee-jerk reactions - where branding an incident as “alcohol-related violence” naturally puts the focus on policies around alcohol service restriction. There is so much more that can be done to keep young people safe at night.

- Why bullshit is no laughing matter — Gordon Pennycook in Aeon:

It is now very common for proponents of alternative medicine to emphasise ‘open-mindedness’. Unfortunately, this can entail disregarding empirical evidence. For example, many anti-vaxxers do not appear to care that Andrew Wakefield’s infamous article in the Lancet in 1998 drawing a link between the MMR vaccine and autism has long been discredited and retracted. Indeed, straight-up explanations of this fact do little to dissuade those who have fallen prey to anti-vaxxer bullshit. Diseases such as measles and mumps are making a comeback in the US and, according to at least one website, there have been more than 9,000 preventable deaths due to failures to vaccinate in the US since 2007. Bullshit is indeed no laughing matter.

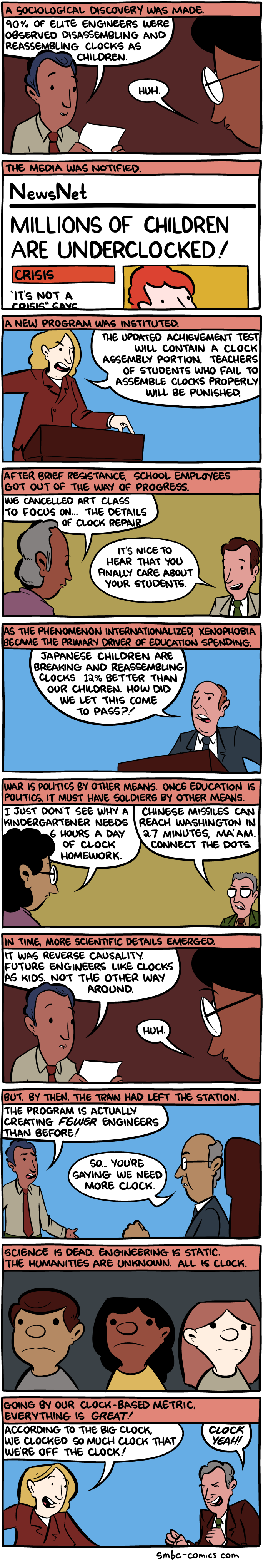

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal by Zach Weinersmith [Yes, education really works like this]:

Sunday, 21 February 2016 - 11:51am

This week, I have entirely caught up on 2015! Next week will be January and February 2016, before uni starts the week after.

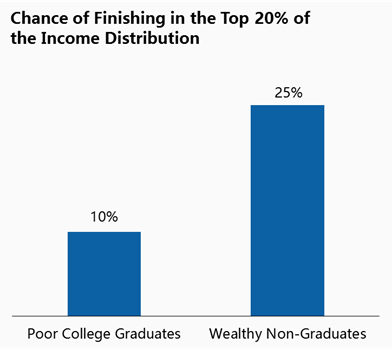

- ‘On the first day of Christmas, my true love gave to me’ … a bunch of econ charts! — Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg in the Washington Post. My pick of these:

- The Melting Away of North Atlantic Social Democracy — Brad DeLong in Talking Points Memo:

Supply-and-demand tells us that when the economy's wealth-to-annual income ratio varies, the rate of profit should vary in the opposite direction. But history tells us that the rate of profit sticks at 5% per year, across eras with very different wealth-to-annual-income ratios. Piketty, however, does not tell us why. Perhaps this is because at a technological level capital does not empower and complement but rather competes with and thus substitutes for labor. Perhaps this is because of successful rent-seeking by the rich who control the government and get it to award them monopoly rents. Perhaps it is because of a social structure that leaves wealth holders believing that a 5% per year is the "fair" rate of profit and are unwilling to underbid each other.

- The road to the workhouse — Frances Coppola is rightly outraged by punitive sanctions imposed on UK benefit claimants:

The workhouse ethic was that work is a moral imperative: people who have no work are morally defective and must be forced to work as a "correction". If they refuse to work, they must be severely punished. The DWP's sanctions regime looks uncomfortably similar. The sick, disabled, mentally ill and unemployed are treated like criminals even though they have committed no crime. A strict penal regime is imposed on them, with extremely harsh punishments for minor transgressions of unfair and arbitrary rules. These punishments affect not only their own health but the health of those dependent on them. Not unlike workhouses, really.

- AIPE: 8000 students in limbo as Sydney college has its registration cancelled — Eryk Bagshaw, Sydney Morning Herald:

A former student of the college, Helen Fielding, told Fairfax Media she was coached over the phone by agents to sign up for a $19,600 diploma of Human Resources Management. The 21-year-old grew up in foster care and has an obvious intellectual disability. "I'm not good at reading," she said at her housing commission flat outside Newcastle.

- Home is where the cartel is — Steve Randy Waldman:

If you buy a home in San Francisco today, the last thing you want to happen is for the housing affordability problem to be solved next year. If apartment prices become reasonable, you’d find yourself with a huge financial loss and an underwater mortgage. […] High rents are like poverty at the Brookings Institution, a problem we claim we desperately want to solve but don’t really want to solve because the things we would have to do to solve it would be costly and disruptive to the people whose interests get termed “we” in a sentence like this one.

- The Sneaky Way Austerity Got Sold to the Public Like Snake Oil — Lynn Parramore of the Institute for New Economic Thinking interviews Orsola Costantini of same:

How do we stop powerful players from co-opting economics and budgets for their own purposes? Our education system is increasingly unequal and deprived of public resources. This is true in the U.S. but also in Europe, where the crisis accelerated a process that was already underway. When children don’t get good educations, the production of knowledge falls into private control. Power gets consolidated. The official theoretical frameworks that benefit the most powerful get locked in.

- Why Philanthropy Actually Hurts Rather Than Helps Some of the World’s Worst Problems — George Joseph, In These Times:

Zuckerberg can legally offer the bulk of his "philanthropy" to any for-profit recipients he wants and still receive public acclaim for "gifting" his fortune. We're seeing the rise of a new, horizontal philanthropy - the rich giving directly to the rich - at a level that's completely unprecedented.

- It's official — benefits and high taxes make us all richer, while inequality takes a hammer to a country's growth — Lee Williams, the Independent:

Thanks to the OECD report, we find that the very thing that the sacrifices of austerity were made to preserve – the growth of the economy – is the very thing they are destroying. Neo-liberal, laissez-faire capitalism extends inequality, we already knew that. But now we have the evidence that inequality harms, rather than encourages growth.

- 'Free Basics' Will Take Away More Than Our Right to the Internet — Vandana Shiva, Common Dreams:

The Monsanto-Facebook connection is a deep one. The top 12 investors in Monsanto are the same as the top 12 investors in Facebook, including the Vanguard Group. The Vanguard Group is also a top investor in John Deere, Monsanto’s new partner for ‘smart tractors’, bringing all food production and consumption, from seed to data, under the control of a handful of investors. […] Smart Tractors from John Deere, used on farms growing patented Monsanto seed, sprayed and damaged using Bayer chemicals, with soil and climate data owned and sold by Monsanto, beamed to the farmer’s cellphone from Reliance, logged in as your Facebook profile, on land owned by The Vanguard Group. Every step of every process right up until the point you pick something up off a supermarket shelf will be determined by the interests of the same shareholders.

More here. - Why Are Universities Fighting Open Education? — Elliot Harmon at Common Dreams:

Though universities tout [patented] technology transfer as a way to fund further education and research, the reality is that the majority of tech transfer offices lose money for their schools. At most universities, the tech transfer office locks up knowledge and innovation, further expands the administration (in a sector that has seen massive growth in administrative jobs while academic hiring remains flat), and then loses money.

Sunday, 14 February 2016 - 1:24pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Guantánamo in New York You’re Not Allowed to Know About — Arun Kundnani, The Intercept:

Mahdi Hashi, a young man of Somali origin who grew up in London, had never been to the United States before he was imprisoned in the 10-South wing of the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan in November 2012, when he was 23. For over three years, he has been confined to a small cell 23 hours a day without natural light, with an hour alone in a slightly larger indoor cage. He has had no physical contact with anyone. Apart from occasional visits by his lawyer, his human interaction has been limited to brief, transactional exchanges with guards and a monthly 30-minute phone call with his family.

- Full employment is a tenet of classic social democracy – but is it still applicable? — Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams in the New Statesman:

While Jeremy Corbyn’s opponents have presented him as a throwback to an old-left style of politics, in fact he has been the only one to recognise the changed realities of the UK in the 21st century. Creating a mental health position in his shadow cabinet, questioning the utility of the Trident nuclear programme and NATO, calling for social support for the self-employed – all these reveal a politics that is very aware of contemporary Britain and its discontents. Meanwhile, his opponents’ prevailing thinking appears mired in the past: a cold-war fascination with obsolete security communities, fond nostalgia for the 1990s, and increasingly punitive attempts to create good workers when good jobs no longer exist.

- Trying to simulate the human brain is a waste of energy — Peter Hankins in Aeon:

It’s as though we decided to build a Tardis immediately, on the basis of the knowledge we have about it now – call it the ‘Blue Box’ project. We know it’s blue, squarish, probably uses electricity for some purposes, makes a whooshy noise, travels in time and is bigger on the inside; let’s get started! Of course, we have no idea how the last two things (the time travel and the strange geometry) are done, but then the brain also does things – subjective experience, intentionality, personhood, to name three – that currently seem to be beyond the reach of either science or philosophy.

- The Basic Income Guarantee: what stands in its way? — Tom Streithorst guestblogging for Frances Coppola:

Fear of scarcity is built into our DNA. For the Basic Income Guarantee to seem viable for most people, they need to learn that demand, not supply, is the bottleneck of growth. We need to recognise that money is something humans create, not something with fixed and limited supply. With Quantitative Easing, central banks created money and gave it to the financial sector, hoping it would stimulate lending. Today, even mainstream figures like Lord Adair Turner, Martin Wolf and even Ben Bernanke recognize that “helicopter drops” of money into individuals’ bank accounts could have been more effective. Technocrats are beginning to recognise the practicality of Basic Income. […] The Basic Income Guarantee solves the problem of demand, stimulates the economy, increases corporate profits, gives workers more freedom, and provides a safety net to the most vulnerable. It is economically sound and politically savvy. But the very rich don’t fear unemployment, they fear redistribution and they will be the most significant force against the implementation of the Basic Income Guarantee.

- The Fed Raises Rates--by Paying the Banks — Marty Wolfson in Dollars & Sense:

Under current Chair Janet Yellen, the Federal Reserve has shown a genuine concern about unemployment, but it is still trapped in its assumptions: There is a “maximum feasible” level of employment. Above that level (or below the corresponding rate of unemployment) inflation will exceed its 2% target. The conclusion from these assumptions is that the Fed should raise interest rates to prevent employment from exceeding the “maximum feasible” level. Instead, the Fed should adopt a real full- employment target: a job for everyone who wants to work. It should adopt a “minimum feasible” target for inflation: the lowest possible rate compatible with full employment. We need a policy perspective in which economic justice for workers is a higher priority than paying the banks.

- Working Paper: The Upward Redistribution of Income: Are Rents the Story? — Dean Baker from CEPR says yes:

This paper argues that the bulk of this upward redistribution comes from the growth of rents in the economy in four major areas: patent and copyright protection, the financial sector, the pay of CEOs and other top executives, and protectionist measures that have boosted the pay of doctors and other highly educated professionals. The argument on rents is important because, if correct, it means that there is nothing intrinsic to capitalism that led to this rapid rise in inequality, as for example argued by Thomas Piketty.

- Good things happen at full employment — Jared Bernstein in the Washington Post:

Dean Baker and I have long contended that at full employment, pressures from labor costs […] mean that firms either have to find new efficiencies, raise prices or start cutting into profit margins. Since they’d generally rather avoid the latter two, full employment can lead to higher productivity growth.

- A Missed Opportunity of Ultra-Cheap Money — Peter Eavis, NYT:

[William A. Galston, a former adviser to President Bill Clinton and now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution] in particular lamented the failure to set up a government-backed infrastructure bank in recent years. “This will go down as one of the great missed opportunities,” he said. Public investment spending as a share of overall economic activity has fallen to lows not seen since the 1940s, according to an analysis by James W. Paulsen of Wells Capital Management.

- Beyond social mobility — Chris Dillow:

A simple thought experiment will tell us that social mobility is nothing like sufficient. Imagine a dictator were to imprison his people, but offer guard jobs to those who passed exams, and well-paid sinecures to those who did especially well. We'd have social mobility - even meritocracy and equality of opportunity. But we wouldn't have justice, freedom or a good society. They all require that the prisons be torn down.

- CEO pay still out of control and diverging again from workers’ earnings — Bill Mitchell:

Two things caught my attention among other things last week. The Australian Tax Office (ATO) released the – 2013-14 Report of Entity Tax Information – which tells us about the total income and tax payable was for 2013-14 tax year for 1539 Australian and foreign companies operating in Australia with incomes above $A100 million. The rather startling revelation is that 579 of the largest Australian companies including Qantas did not pay any tax at all in that financial year. The second (unrelated but pertinent) report was released last week by the British Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) – The power and pitfalls of executive reward: a behavioural perspective – which found that the increasing gap between British CEO earnings and their employees is unrelated to company performance and reflects “self-serving tendencies”.

- Dear Parents: Everything You Need to Know About Your Son and Daughter’s University But Don’t — Ron Srigley in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

First, [sessional contract staff] are not scholars but employees. They think of administrators as people they work for rather than people who work for them by supporting their teaching and research. Second, they are vulnerable and therefore remain mostly silent about critical matters. If a sessional instructor complains publicly about her institution or its declining standards, she will do so only once. […] Finally, the very act of employing, empowering, and often elevating such people denigrates real scholars and scholarship by definition. If a person who knows next to nothing of what you know can do what you do just as well as you do it, then what is the value of what you know?

- Finland's hugely exciting experiment in basic income, explained — Dylan Matthews in Vox:

The idea is to see what happens to a community under a basic income, rather than just to individual people. Having a whole town get benefits could have cascading effects as households escape poverty, as some people use the income guarantee as insurance so they can take risks and form companies, as universities see increased enrollment from people better able to afford supplies, etc. "If people in a smaller area are getting the benefits, their behavior vis-a-vis other people will change, employers and employees will change their behavior, encounters between clients and their street-level bureaucrats (social workers, employment offices, etc.) will change, and the interplay between different bureaucracies will change," Kangas says.

- Love from mom and dad … but who gains from Mark Zuckerberg’s $45bn gift? — Linsey McGoey in the Guardian:

As if sensing that our newfound effervescence had fizzled rather abruptly, a crack team of management scholars and business journalists took up arms, manning airwaves and TV stations and the open-planned domiciles of new media startups funded by tech entrepreneurs based in Hawaii – and tried to cheer us with a single message. You’re right, they conceded. It’s not charity. But here’s the thing: it’s better than charity. It’s a new, radical movement that we like to call “philanthrocapitalism” – and it’s going to make you all rich. How, you might ask? By giving more philanthropy to the wealthy.

- The IMF Changes its Rules to Isolate China and Russia — Michael Hudson:

A nightmare scenario of U.S. geopolitical strategists is coming true: foreign independence from U.S.-centered financial and diplomatic control. China and Russia are investing in neighboring economies on terms that cement Eurasian integration on the basis of financing in their own currencies and favoring their own exports. They also have created the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as an alternative military alliance to NATO. And the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) threatens to replace the IMF and World Bank tandem in which the United States holds unique veto power.

- The world of threats to the US is an illusion — Stephen Kinzer in the Boston Globe:

I recently asked a United States Navy officer what threats he believed the United States might confront in the future. To my astonishment, he answered, “Venezuela.” The South American country is in political crisis and careening toward bankruptcy. Its combat navy counts six frigates and two submarines, none of them seaworthy. Yet last month President Obama designated Venezuela an “extraordinary threat to US national security.” The search for enemies can lead to odd places.

- Piketty and the Australian exception — John Quiggin at Crooked Timber:

Australia’s relatively equal distribution of income and wealth depends on a history of strong employment growth and a redistributive tax–welfare system. Neither can be taken for granted. […] The move towards a patrimonial society already happening in the US is evident at the very top of the Australian income distribution. As in the US, the claim that the rich are mostly self-made is already dubious, and will soon be clearly false. Of the top 10 people on the Business Review Weekly (BRW) rich list, four inherited their wealth, including the top three. Two more are in their 80s, part of the talented generation of Jewish refugees who came to Australia and prospered in the years after World War II. When these two pass on, the rich list will be dominated by heirs, not founders.

Sunday, 7 February 2016 - 12:59pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The political aftermath of financial crises: Going to extremes — Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick, Christoph Trebesch at VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal:

The bottom line is that financial crises stand out. They are followed by significantly more political instability than other types of economic crises. This raises the question – why are financial crises different? One explanation is that financial crises may be perceived as endogenous, ‘inexcusable’ problems resulting from policy failures, moral hazard and favouritism. In contrast, non-financial crises could be seen as ‘excusable’ events, triggered by exogenous shocks (e.g. oil prices, wars). A second potential explanation is that financial crises may have social repercussions that are not observable after non-financial recessions. For example, it is possible that the disputes between creditors and debtors are uglier or that inequality rises more strongly. Lastly, financial crises typically involve bailouts for the financial sector and these are highly unpopular, which may result in greater political dissatisfaction.

[Also:] - Right-wing political extremism in the Great Depression — Alan de Bromhead, Barry Eichengreen, Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke at VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal:

Our statistical results […] show that that the Depression was good for fascists. It was especially good for fascists in countries that had not enjoyed democracy before 1914; where fascist parties already had a parliamentary base; in countries on the losing side in WWI; and in countries that experienced boundary changes after 1918. […] Importantly, it shows that what mattered was not the current growth of the economy but cumulative growth or, more to the point, the depth of the cumulative recession. One year of contraction was not enough to significantly boost extremism, in other words, but a depression that persisted for years was.

- Can philosophy survive in an academy driven by impact and employability? — Simon Blackburn (et al.) in the Times Higher Education:

One of the most potent causes of mistrust of philosophy is that it provides no answers, only questions, so that to many it does not seem to have progressed since its very beginnings in Plato, or even in pre-Socratic Greece (or China or India). Of course, one might similarly ask whether other human pursuits, such as music, literature, drama, architecture, painting or politics, have “improved” (and by what measure this judgement is supposed to be made), and if the answer is at best indeterminate we might query whether this reflects badly on those practices, or whether perhaps it indicates a problem with the question.

- Changing private investment activity requires higher fiscal deficits — Bill Mitchell:

So if non-financial corporations are themselves increasingly becoming net lenders to the rest of the economy then the idea that household saving provides the investment funds for firms has to be questioned. Further, this shift in behaviour implies a serious new leakage to aggregate demand has developed, which if left unchecked would bias the economy to recession. The mainstream alternative is that growth is maintained by rising consumer spending by households driven by increased credit. In other words, the lenders and the borrowers have swapped seats. Of course, such a growth scenario is unsustainable because households cannot cope with ever-increasing levels of debt, as we learned in 2008.

- IMF forgives Ukraine’s Debt to Russia — Michael Hudson:

[O]n Tuesday, the IMF joined the New Cold War. It has been lending money to Ukraine despite the Fund’s rules blocking it from lending to countries with no visible chance of paying (the “No More Argentinas” rule from 2001). When IMF head Christine Lagarde made the last IMF loan to Ukraine in the spring, she expressed the hope that there would be peace. But President Porochenko immediately announced that he would use the proceeds to step up his nation’s civil war with the Russian-speaking population in the East – the Donbass. […] By doing so, it announced its new policy: “We only enforce debts owed in US dollars to US allies.”

- House Prices and Job Losses — Emma Lyonette and Gabor Pinter, Bank Underground:

This blog summarises the findings of recent research by Pinter (2015) that emphasises the role of real estate as an important determinant of firms’ borrowing capacity. This is because real estate is widely used by corporates as collateral when trying to obtain external financing. Fluctuations in real estate prices may therefore cause fluctuations in firms’ borrowing capacity, which then affects firms’ decisions to undertake new investment, to create new jobs and to destroy existing jobs. The paper shows that this so-called collateral channel is important in understanding not only the recent Great Recession but historical UK business cycles in general.

- Simpson, PL, Guthrie, J, Lovell, M, Doyle, M and Butler, T 2015, 'Assessing the Public’s Views on Prison and Prison Alternatives: Findings from Public Deliberation Research in Three Australian Cities', Journal of Public Deliberation, Vol. 11, No. 2:

Despite decreasing crime victimisation rates in Australia, incarceration rates have doubled over the last thirty years. Australia’s use of imprisonment has major economic and social equity costs, especially given the over-representation of Indigenous Australians and other socially disadvantaged groups in prison. Evidence increasingly points to the limitation of incarceration as a tool for effective offender rehabilitation suggesting that a new policy agenda on responses to offending is warranted. Yet, public opinion is generally assessed and perceived to hold punitive views towards offenders.

- Sorry, but Your Favorite Company Can’t Be Your Friend — Josh Barro in the New York Times:

As social psychologists describe it, there are two broad categories of human relationships: exchange relationships, in which we trade for mutual benefit; and communal relationships, which are based on mutual caring and support. Normally, you are supposed to have the former with people you do business with and the latter with your friends and relatives. But sometimes, companies try to blur the lines, insinuating themselves into your friend zone.

- Working Until It’s Time for Your Grave — Tiffany Williams, Common Dreams:

My [Institute for Policy Studies] colleagues recently released a report on the retirement gap between CEOs and workers. They found that nearly half of working age Americans have no access to retirement plans through their jobs. When I asked my mom about her own retirement savings, I learned she had nothing at all.

- The Potential of Debtors’ Unions — the Debt Collective in ROAR Magazine:

Experienced alone, debt is isolating, frightening and morally laden with shame and guilt. Indebtedness is being afraid to open the mail or pick up the phone. But as a platform for collective action, debt can be powerful. Consider oil tycoon JP Getty’s adage: “If you owe the bank $100 that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s the bank’s problem.” Student debt alone stands today at $1.3 trillion. Together, we can be the banks’ problem.

- Humans vs Houses: Australia's perverse tax system — Cameron K. Murray:

It is certainly now time for the government to end these tax concessions for investment property. Raising the GST, the current government’s preferred tax policy, is probably the worst choice in terms of both equity and efficiency compared to the low-hating fruit of removing these property tax advantages which currently cost the budget about $11billion a year. Obviously removing them would change incentives, reduce prices, and so forth, meaning that actual budget gains from their removal will be lower. But even so, the shift of incentives across the economy would be hugely advantageous in terms of both efficiency, and equity, as these tax incentives primarily benefit the wealthy.

- How George Osborne exploited our psychological biases to secure his cuts — Ben Chu in the Independent:

Mr Osborne’s July Budget proposed to save £4bn a year by 2020 by freezing all working age benefits in cash terms for the next four years, meaning a deep cut after inflation for recipients. And that was actually a bigger saving than the one generated from the cuts to tax credits. But unlike the tax credit cuts, the benefit freeze prompted no outcry. Why? Because the immediate cash losses loomed far larger than the forgone gains of benefits rising in line with inflation.

- Education and Equality in the 21st Century — Danielle Allen, Crooked Timber:

The preparation of citizens, through education, for civic and political engagement supports the pursuit of political equality, but political equality, in turn, may well engender more egalitarian approaches to the economy. An education that prepares students for civic and political engagement brings into play the prospect of political contestation around issues of economic fairness. In other words, education can affect income inequality not merely by spreading technical skills and compressing the income distribution. It can even have an effect on income inequality by increasing a society’s political competitiveness and thereby impacting “how technology evolves, how markets function, and how the gains from various different economic arrangements are distributed.”

- Nobody's home: Housing boom leaves swathe of empty properties — Angus Whitley in the Age on a new report from the Henry Georgists at Prosper Australia:

Sudden property price declines or an economic slowdown risk unmasking the vacant supply. Owners would start to sell up or look for rental income to cushion the blow from falling prices, [Catherine Cashmore, author of the Prosper report] said. "Suddenly, you find there's no one there to buy it or nobody to rent it. That's a common pattern in a housing crash," Cashmore said. "What we're trying to do is it to make it visible before it happens."

- Corbyn – after Oldham — Geoffrey Heptonstall, openDemocracy:

The headlines should have read: ‘Big Swing to Labour Boosts Corbyn at Critical Time.’ The fact is that the phrase ‘swing to Labour’ was suspiciously absent. The affirmation of Jeremy Corbyn’s position was conceded with something close to a snarl.

- In support of a Universal Basic Income – introducing the RSA Basic Income Model — Anthony Painter, RSA:

A couple of years ago, I was told of two young mothers who were studying for a qualification in nursing care. Towards the end of their studies a local Job Centre Plus insisted that they make themselves available for work or face sanction. They left their course and failed to qualify. They lost out and their time had been wasted. They were locked in the same oscillation between benefits and poor quality work. And society lost too - we need nursing care workers.

- Donald Trump and the ugliness in Las Vegas — Michael A. Cohen, Boston Globe:

But there is another side to Trump that merits greater attention — fear. This is not the fear of “others” — immigrants, Muslims, etc. There is plenty of that, but in talking to Trump’s supporters, a different kind of fear emerges — a sense that the country is falling apart, that the nation’s safety and security are at risk, and that America needs someone who is strong, decisive, and unafraid to say what he thinks must be done to fix things.

- This week, the US government will take action to slow the economy and prevent wage growth — Matt Yglesias at Vox:

The Federal Reserve is structured as an independent agency precisely on the theory that for the long-term good of the economy we sometimes want the central bank to slow the pace of job creation in order to avoid inflation, even though standing in front of a podium and saying, "I want to slow the pace of job creation" sounds terrible. But the weird thing about this week's push for higher interest rates is that there's no inflation problem to solve.

- Australian government fiscal outlook – irresponsible and will fail — Bill Mitchell:

Basically, the Outlook shows that the federal fiscal deficit is larger than previously estimated (in the May 2015 Fiscal Statement aka ‘The Budget’) and this demonstrates the automatic stabilisers in operation to put a floor under the slowing economy. This counter-cyclical movement is something that we should be comforted by because as private spending contracts and the economy slows the expansion of the deficit limits, to some extent, the job losses and the number of businesses that might become insolvent. However, the mainstream reaction has been hysterical (as in hysteria) with all sorts of predictions about national insolvency, credit rating agencies downgrading us, and “deficits for as long as you can see”. The problem is that the so-called average Australian believes all this nonsense and doesn’t understand that the rising deficit is a good thing in the context of poor developments in private spending. […] A career of reading this junk leads me to wish I’d become an anthropologist or something else like that.