Sunday, 20 March 2016 - 4:25pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

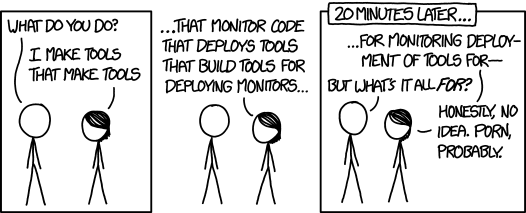

- Tools — xkcd:

- Impossible possibilities for Keynes’s grandchildren — David F. Ruccio:

[W]hat Keynes did not understand is that workers don’t just produce wealth, which they can then enjoy by reducing the amount of work they do. They produce wealth that stands opposed to them, wealth in the form of capital, which is then used to render part of the working population superfluous, thus dragging down the wages of other workers, who are then employed to boost the profits of their employers. The workweek of the employed population doesn’t decrease, even as they are joined to new technologies and are transferred to new sectors of the economy.

- Shortly after her death, Harper Lee's heirs kill cheap paperback edition of To Kill a Mockingbird — Cory Doctorow, Boing Boing:

A court upheld the sealing away of Lee's will from public view, so it's impossible to say for sure what prompted the move, but this much is clear: schools that assign "To Kill a Mockingbird" -- one of the most commonly assigned books in US classrooms -- will have to pay a lot more for their books, and that money will not, and cannot, benefit the author.

- The Story of Our Economy in 2015: A cocktail of household consumption, household consumption, and more household consumption — Frank Van Lerven at Positive Money:

The OBR forecasts that real GDP growth will average 2.3-2.5% a year between 2016 and 2020. This growth is meant to take place despite the reduction in government expenditure. As we have suggested before, considering that the UK is not a net exporter, if the government decides to reduce its level of debt then the domestic private sector has to take on more debt for there to be any growth. Increasing levels of private sector debt, (business and household borrowing), will be called upon to drive growth in the years to come.

- The co-option of government by transnational organisations — Bill Mitchell:

The process of privatisation clearly transferred resources from the public sector to the private sector and reduced the public bureaucratic control of the organisations in question. Those processes are reversible. If we want a demonstration of that reversibility, then we need not look further than what happened to the banking sector in the early days of the GFC when many national governments effectively socialised the losses from the failed corporate strategies, protected depositors and nationalised the organisations. There was no hint then that the nation-state had lost its power or discretion to act to advance the national interest and largely disregard the interests of the private shareholders of these large transnational, financial entities.

- Despair Fatigue — David Graeber in The Baffler:

True, most mainstream economists are capable of seeing through obvious nonsense, like the justifications proposed for fiscal austerity. But the discipline is still trying to solve what is essentially a nineteenth-century problem: how to allocate scarce resources in such a way as to optimize productivity to meet rising consumer demand. Twenty-first century problems are likely to be entirely different: How, in a world of potentially skyrocketing productivity and decreasing demand for labor, will it be possible to maintain equitable distribution without at the same time destroying the earth? Might the United Kingdom become a pioneer for such a new economic dispensation?

- A thought experiment for Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull — Steve Keen in Business Spectator:

Imagine that there is an economy where the money supply consists of a single dollar, which is exchanged 100 times per year among this economy’s inhabitants — thus generating a GDP of $100 per year. Then imagine that the government in this economy sets itself the target of running a surplus equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP. If the government achieves its objective, what will GDP be the following year? Zero. And, if the government debt ratio was more than 1 per cent beforehand, it will be infinite afterwards. Why? Because the economy had only one dollar of money in existence, and the government’s surplus took that $1 out of circulation, leaving the economy with precisely zero dollars for commerce the following year. The government budget affects GDP by changing the amount of money in circulation in the economy, and a government surplus effectively destroys money.

- Are luxury condo purchases hiding dirty money? — Husna Haq at the Christian Science Monitor:

In fact, using shell companies, or limited liability companies, to hide a buyer's identity is actually relatively common, and legal. But the practice could drive up real estate prices in some markets, and contribute to real estate booms. Federal authorities are also concerned that the practice enables foreign buyers to easily find a safe haven for illicit money in American real estate.

- How does the 1 percent capture the surplus? — David Ruccio:

The basic idea is that “pass-throughs”—businesses whose annual income is taxed at the owner-level (such as partnerships and S-corporations)—now account for more than half of all U.S. business income, thus passing traditional (so-called C) corporations. […] 54.2 percent of U.S. business income in 2011 was earned in the pass-through sectors, compared to only 20.7 percent in 1980.

- "Neoliberalism" is it? — Jeremy Fox takes on Will Davies' challenge of a week earlier in openDemocracy:

Compared with some other candidates, ‘neoliberalism’ does not seem to be an especially elusive abstraction. I take it to mean marketisation of the public realm as a political project. Its current popularity among political leaders of a certain hue is that it has the appearance of offering value-free decision-making because it allows market competition rather than ideological bias to determine value. They are thereby absolved, at least in theory, from responsibility for the provision of important public services.

- Why you shouldn’t let your smartphone be the boss of you — Peter Fleming in the Guardian:

According to an influential group of neoliberal economists working in the 1970s, people ought to see themselves as “human capital” rather than human beings. This sort of capital is a never-ending investment, continuously enhanced in relation to skills, attitude and even physical appearance. Work is crucial for building this capital, perhaps its defining source. This is where employment and life more generally slowly merge and become indistinguishable from each other. A job is no longer something we do to achieve socially productive goals in society. An activity among other pursuits. No, a job today is something we are … preferably 24/7. Working unpaid overtime therefore seems natural. Self-exploitation looks like personal freedom.

- The return of public investment — Dani Rodrik:

If one looks at the countries that, despite strengthening global economic headwinds, are still growing very rapidly, one will find public investment is doing a lot of the work.

- Diane Coyle finds Minsky, but misses Keynes — Geoff Tily, Prime Economics:

Now Keynes was no trivial figure. How can it not be “interesting” that one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century was misrepresented by the academic economics profession, and this misrepresentation has been denied ever since? How can what he actually said not be interesting, once we recognise that what we thought he said was wrong? How can his work not be interesting if it treats finance and the shortcoming of conventional macroeconomics is that it doesn’t treat finance?

- Ultra-Rich 'Philanthrocapitalist' Class Undermining Global Democracy: Report — Sarah Lazare at Common Dreams:

A study just out from the Global Policy Forum, an international watchdog group, makes the case that powerful philanthropic foundations—under the control of wealthy individuals—are actively undermining governments and inappropriately setting the agenda for international bodies like the United Nations. The top 27 largest foundations together possess assets of over $360 billion, notes the study, authored by Jens Martens and Karolin Seitz. Nineteen of those foundations are based in the United States and, across the board, they are expanding their influence over the global south. And in so doing, they are undermining democracy and local sovereignty.

- 5 outrageous things educators can’t do because of copyright — Lisette Kalshoven in Medium:

The current patchwork of copyright exceptions for education at the member state level can lead to absurd situations for teachers that want to utilize creative works. We asked friends from across Europe to submit examples showing where copyright and education do not mix. You can cry (or laugh) with us.