Inflation

Measuring Price Inflation and Growth in Economic Well‑Being with Income‑Dependent Preferences

How can we accurately measure changes in living standards over time in the presence of price inflation? In this post, I discuss a novel and simple methodology that uses the cross-sectional relationship between income and household-level inflation to construct accurate measures of changes in living standards that account for the dependence of consumption preferences on income. Applying this method to data from the U.S. suggests potentially substantial mismeasurements in our available proxies of average growth in consumer welfare in the U.S.

These insights and results are based on my recent research paper coauthored with Xavier Jaravel of the London School of Economics, which is forthcoming at the Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Background

Economic theory shows that we can approximate changes in living standards using straightforward formulas known as price and quantity indices. These indices combine observed data on changes in the quantities of what we consume and the prices of those items, and are widely used by statistical offices around the world to construct measures of overall inflation in the cost of living and growth in living standards. However, this approach hinges on a crucial assumption—that the composition of what we want to buy does not shift when our incomes do (see, for example, Diewert 1993). Unfortunately, this simplifying assumption, known as homotheticity or income invariance, does not match up with a host of real-world evidence on the dependence of consumption patterns on consumer income, going as far back as the work of Engel (1857). Recent evidence on inflation inequality—the strong relationship between income and household-level measures of inflation—underscores the importance of this problem.

Insight and Method

A conceptually coherent way to measure living standards is to fix a set of prices and calculate the monetary expenditure needed, under these prices, to achieve any level of consumer welfare as it changes over time. Let us refer to this concept as real consumption, to distinguish it from the nominal expenditure of the consumer under changing prices. For instance, consider a case where all prices rise at the same 2 percent rate from one year to the next due to general inflation. Here, a consumer whose nominal expenditure has risen by 5 percent only experiences a 3 percent increase in real consumption, if we fix the prices in the initial or the final year. The key question is how to calculate the corresponding measures of inflation and real consumption growth in real-world settings in which changes in prices vary across different goods and services.

If consumer preferences are income-invariant, everyone consumes the same basket of goods and services regardless of their income level. Over time, households adjust whether to consume more or less of each good or service based on how its price changes relative to others, but these adjustments are the same for everyone. Conventional price indices tell us how to average these price changes using the expenditure shares of different goods and services, and theory tells us we need to deflate the growth in nominal expenditure based on the value of this average, which is the standard measure of inflation.

In reality, households choose different baskets of goods and services that systematically depend, among other things, on their income. Therefore, we find different inflation measures for different households when we compute the price indices using each household’s own expenditure shares, something that should not happen under the conventional assumption of income invariance. In the data, we often find lower inflation measures for richer households, meaning that prices rise more slowly for luxuries—i.e., items that are more heavily purchased by richer consumers (see, for example, Hobijn and Lagakos 2005, McGranahan and Paulson 2006, Jaravel 2019, Avtar et al. 2022, and Chakrabarti et al. 2023). Therefore, these items are becoming relatively cheaper than the others over time. This implies that, if we fix the initial prices as our basis for measuring real consumption, households that experience rising income will be shifting their consumption toward items that are accumulating relative price declines. In other words, sustained inflation bias toward necessities—goods and services favored by poorer households—means that we need relatively lower rates of growth in nominal terms to maintain the same rate of growth in real consumption. Thus, when income is growing, consumers are actually better off than that suggested by all available measures of real consumption. The conventional measures of inflation and real consumption miss this mechanism altogether. This is even true of the more recent work on inflation inequality, partially cited above, that relies on household-specific price index formulas but does not explicitly account for income dependence.

As it turns out, there is a relatively easy fix for this problem. We can correct for the effects of this income dependence in preferences simply by estimating the relationship between household income and household-specific price indices. The slope of this relationship leads to a correction factor that we need to apply to the nominal expenditure growth after it is deflated by the household’s own price index. This method is fairly easy to implement and only requires access to widely available surveys of consumption expenditure at the household level. Moreover, it can be generalized to extend to other household characteristics, such as age, family size, and education, that (1) matter for the composition of their consumption expenditure, and (2) potentially vary over time at the household level.

Application to the U.S. Data

In the paper, we apply our approach to data from the United States and quantify the magnitude of the bias in conventional measures of real consumption growth that ignore the effects of income dependence in household preferences. We build a new linked dataset providing price changes and expenditure shares at a granular level from 1955 to 2019, across the different percentiles of household (pretax) income. This dataset combines several data sources, primarily drawing from disaggregated data series available from the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX). This new linked dataset allows us to provide evidence on the inequality in inflation over a long time horizon, thus extending prior estimates that have focused on shorter time series.

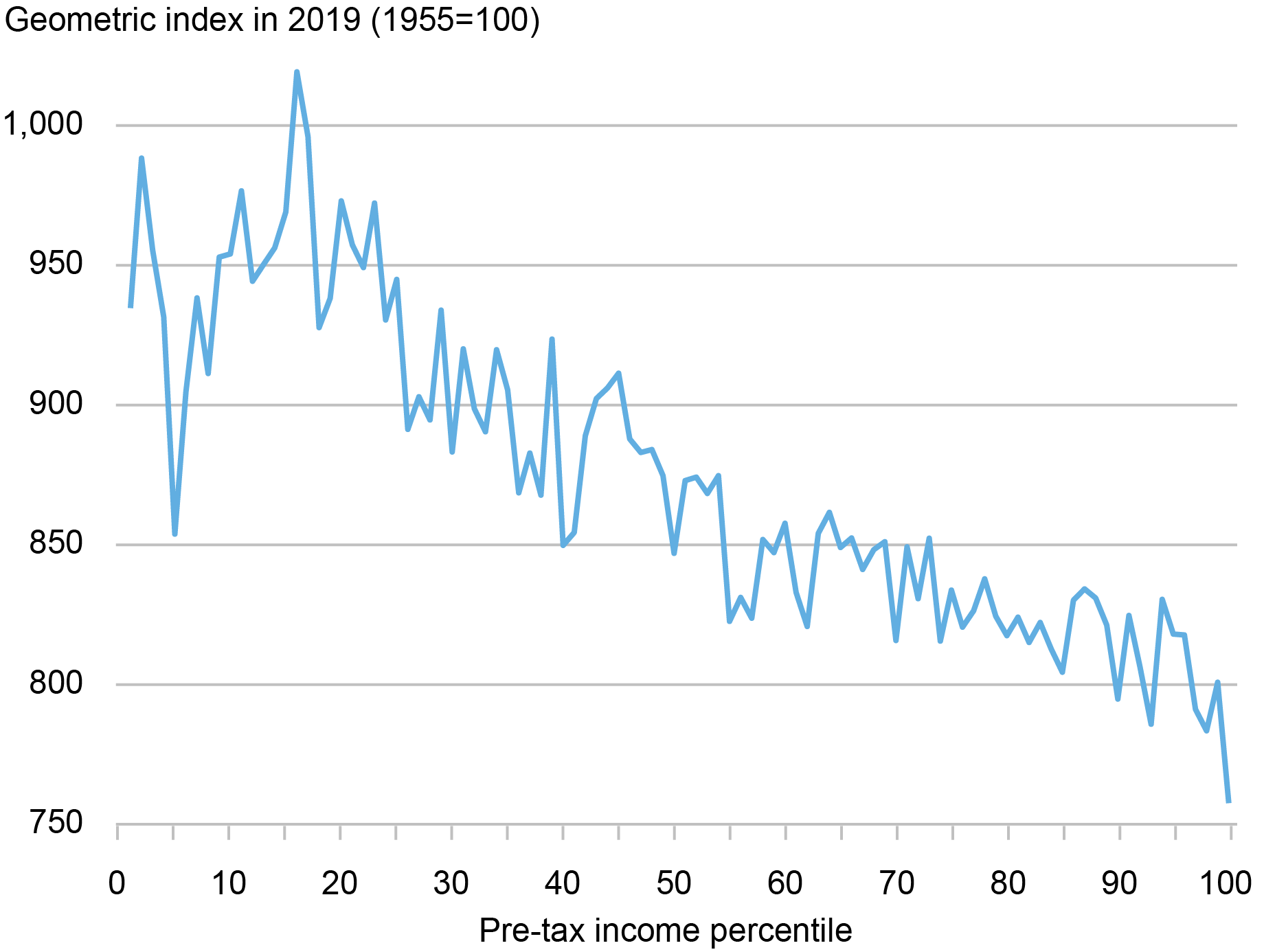

Computing inflation using income-percentile-specific price index formulas, we find that inflation inequality is a long-run phenomenon. For instance, as the chart below shows, we find that cumulative inflation from 1955 to 2019 varies substantially for households with different levels of income: while prices have inflated by a factor of around 10 for the bottom income groups, they have inflated by a factor closer to 8 at the top of the income distribution. The gap in inflation experienced by different income percentiles is sizable when compared to the overall size of inflation over the period. As such, when we look into the past from the perspective of today’s prices, we observe that (1) households were on average poorer sixty-five years ago—that is, they had stronger preferences for necessities; and (2) necessities were cheaper relative to luxuries. These empirical patterns imply that consumer welfare was higher sixty-five years ago when accounting for the dependence of preferences on income.

Inflation Inequality over the Long Run

Source: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: This chart shows the patterns of inflation inequality in the data. It shows the cumulative inflation rates between 1955 and 2019 by pretax income percentiles.

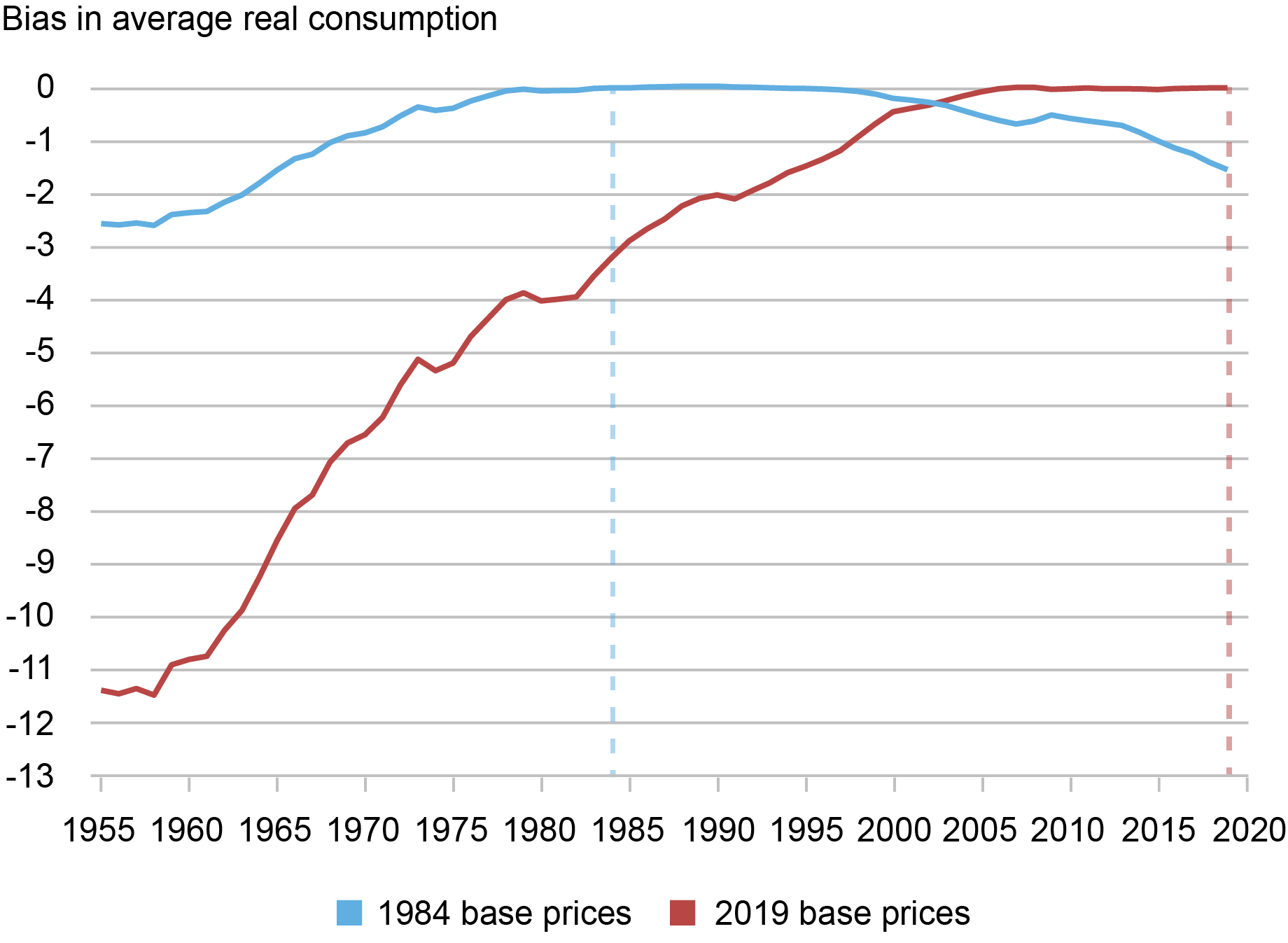

When we apply our new method to this data, we find that the magnitude of the correction in measured welfare growth due to the effect of income-dependent preferences can be large. For example, as the chart below shows, by fixing prices in 2019 as the basis of defining real consumption, we find that the uncorrected measure underestimates average real consumption (per household) in 1955 by about 11.5 percent. Note that, by definition, the error is zero in the base year and accumulates over time as we move in time—in this case backward—away from the base year. For comparison, we also show the results if we fix prices in 1984. In this case, the bias is smaller simply because it accumulates over a shorter time period, as we move away from the base year in our data.

Bias in Conventional Measures of Average U.S. Real Consumption (1955-2019)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: This chart reports the biases in the level of average real consumption per household in conventional measures of real consumption, when compared against the corrections implied by our method, under two choices for the fixed prices as the base for calculation of real consumption: prices in 1984 and in 2019.

Of course, bias in measuring the level of real consumption leads to corresponding biases in the estimated growth. As the chart above already indicates, if we fix prices in the most recent year (2019), the conventional estimates overestimate the rate of growth in average real consumption due to the negative bias in the levels. In particular, the uncorrected measure of cumulative real consumption growth is 270 percent over the entire 1955-2019 period, or 2.07 percent growth annually. In contrast, with our correction for income dependence and under 2019 base prices, cumulative consumption growth falls to 232 percent, or an annualized growth rate of 1.89 percent per year. Thus, in this case we find that the annual growth rate from 1955 to 2019 is lowered by 18 basis points (2.07 percent − 1.89 percent).

Note that, since the conventional measure always underestimates the level of real consumption, the sign of the error in measured growth of real consumption depends on the choice of the base prices. For instance, if we instead fix 1984 prices as our base, the chart shows that the conventional measures in fact underestimate the growth in real consumption between 1984 and 2019. In other words, since preferences are income-dependent, measured growth in real consumption should in principle depend on the choice of fixed prices to express the measure.

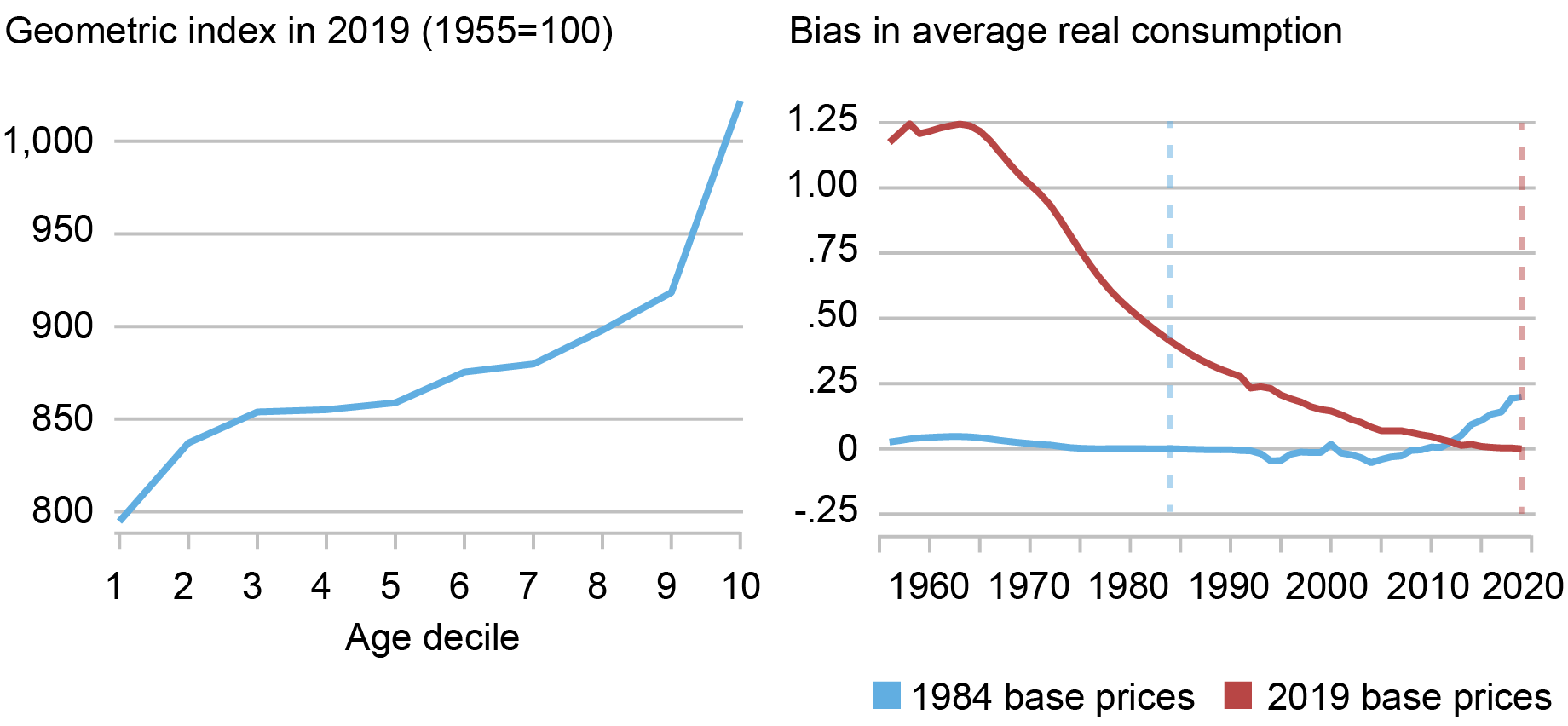

Finally, we also apply our generalized method to quantify the adjustment to average real consumption implied by consumer aging in the United States. In this case, we reconstruct our measures of inflation by deciles of age and income by, first, defining ten deciles of the (pretax) income and, then, computing ten age deciles within each income decile. Using this data, as the chart below illustrates, we document a strong positive relationship between consumer age and inflation, which alters the measurement of real consumption because the average consumer age increases over time. We find that the implied adjustments to real consumption are economically meaningful but much smaller than the correction due to income dependence, which justifies our focus on the latter.

Consumer Aging and Real Consumption (1955-2019)

Sources: Author’s calculations based on the historical linked CEX-CPI data.

Notes: The left panel of the chart reports the cumulative inflation in the United States, from 1955 to 2019, for each decile of age. The right panel reports the implied bias in the average level of real consumption per household in conventional measures of real consumption, when compared against the corrections implied by our method due to aging, under two choices for the fixed prices as the base for calculation of real consumption: prices in 1984 and in 2019.

Conclusion

Our results may have important implications for the way in which national statistical agencies around the world construct measures of inflation and real economic value. In particular, the empirical results presented above suggest an approach that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) can use, based on already available data, to construct improved measures of real consumption growth and inequality in the U.S. In addition to improving the measurement of long-run growth and inflation inequality, our new approach can have important policy implications, such as the indexation of the poverty line and a more efficient targeting of welfare benefits. This approach also provides a blueprint for distributional national accounts (Piketty et al. 2018) that account for inflation inequality and income dependence in household preferences.

Danial Lashkari is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Danial Lashkari, “Measuring Price Inflation and Growth in Economic Well‑Being with Income‑Dependent Preferences,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 8, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/01/measuring-price-in....

Was the 2021-22 Rise in Inflation Equitable?

Inflation Disparities by Race and Income Narrow

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

So-called ‘Team Transitory’ declared victors

On June 8, 2021, the UK Guardian published an Op Ed I wrote about inflation – Price rises should be short-lived – so let’s not resurrect inflation as a bogeyman. In that article, and in several other forums since – written, TV, radio, presentations at events – I articulated the narrative that the current inflationary…

Podcast Failures: Friedman and Chile, Hume and Public Debt

I listen to a few podcasts during my commute. Two that I often appreciate are Know Your Enemy, associated with Dissent Magazine,* a series of interviews on mostly right wingers by Matthew Sitman and Sam Adler-Bell, and Past, Present and Future, a series of monologues by David Runciman, sponsored by the London Review of Books. Both are always entertaining and informative. I'm not a specialist in most of the subjects they discuss. However, two recent episodes (or at least I listened to them recently), one from

each, dealt with economic issues, and they did leave a lot to be

desired, to say the least.

Very briefly, the issue with the interview with Jennifer Burns about her biography (in many ways, from this interview, and the one with Tyler Cowen, it is hard not to see it as a hagiography; more on that as soon as I read the book; it's been ordered. I hope that's just a perception and that the book provides a more balanced view of his contributions and political views) of Friedman is that the hosts accepted almost all of her very monetarist interpretation of the Allende government, and her whitewashing of Friedman's relation with the Pinochet regime (see on that this and this). In all fairness, at least one of the hosts (sorry, not sure that was Matt or Sam) questions (around 1:16) the validity of her interpretation of the relation of Friedman with the regime. But there seems to be a complacent view according to which inflation in Chile was caused by excessive monetary printing driven by the expansion of the welfare state.

The role of the US sanctions, and Nixon's infamous instruction to "make the economy scream" are never cited. And the lack of dollars was at the center of the depreciation of the currency, inflation and the collapse of the economy. Let alone that the Pinochet period wasn't that good (yes they do claim that it created the basis for future growth, a typical conservative trope, that I should write about; in another occasion). I also recommend this post by Tom Palley. On a general evaluation of the regime see this piece by Jim Cypher in Dollars & Sense.

The issues with Runciman's podcast are considerably more problematic. They don't entail a misrepresentation of the ideas of a crucial intellectual, in this case, David Hume. In fact, Runciman is relatively correct when it comes to Hume's essentially negative views of public debt (which were not all that different than those of Adam Smith, at least according to Donald Winch**; btw it was called public credit at that time, so nothing weird about it). He makes to much of Hume's drastic solution, default, for public debt, and its comparison with suicide, for the nation not the individual. And he does recognize that events essentially proved Hume wrong.

But then he commits all of Hume's (and modern mainstream economics). Presumes that the only way out of debt is to run persistent surpluses, printing money and reducing its value in real terms (endorsing a Monetarist view of inflation; it's amazing how pervasive it is), and default. He misses that debts can fall as a share of income (GDP), that is, the ability to repay, if the economy grows faster than debt (the rate of interest), and that most debt consolidations actually happened that way, while running deficits. He also gives Argentina as an example of a country that has defaulted without noticing the differences between debt in domestic and foreign currency. It's a mess. Worse, in an environment in which many conservatives want to promote default in the US he suggest that talking about it would be reasonable. He is out of his depth, should apologize and invite someone to explain the problems with his analysis.

Again, I'm only commenting on these two episodes, because they do seem off, when compared to the quality of both podcasts in general.

* I published almost 20 years ago on Dissent. Because of this I did search their online archive and my piece, and my name was misspelled. Also, it was published in the Winter of 2004, and not of 1984. In the original magazine it was spelled correctly. Oh well.

** See Donald Winch, "The political economy of public finance in the 'long' eighteenth century," in John Maloney (ed.), Debt and Deficits: An Historical Perspective, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1998.

Top Posts of 2023

Well, another year of blogging is over.

For me, it was a year of research themes. I spent the first half of 2023 debunking interest-rate orthodoxy. Then I spent the second half of the year studying the world’s billionaires. Here were the top 5 posts:

- Do High Interest Rates Reduce Inflation? A Test of Monetary Faith

- How Interest Rates Redistribute Income

- Interest Rates and Inflation: Knives Out

- Mapping the Ownership Network of Canada’s Billionaire Families

- Interest Rates and Unemployment: An Underwhelming Relation

A big thanks to my blog patrons, who’ve made it possible for me to do economic research outside of academia. If you’d like to support my work, you can do so here:

Thanks for reading,

Blair

The post Top Posts of 2023 appeared first on Economics from the Top Down.

A short note on Argentina's depreciation, inflation and possible dollarization

That Argentina is in for a major crisis is, I think, pretty clear and well-known. I won't delve too much on the political aspects of what Finchelstein refers to as wannabe Fascistic tendencies of the new president. Today a major protest should take place, and the same people that suggested that Peronists groups forced the recipients of social transfers to participate (something that was never proved) under threat of being cutoff, are threatening to cutoff those that participate. You know, because they defend individual liberties and all.

First of all, the economic plan (and many heterodox authors had been calling for what exactly done) was simply maxi-depreciation, of 100 percent, of the official exchange rate, to try to close the gap with the parallel market (or blue) rate, and the announcement of a massive fiscal adjustment, supposedly of about 5 percent of GDP. As discussed here several times, the effects of these policies are certainly a significant acceleration of inflation, and a massive recession. These are well-known effects of a maxi-depreciation. Prices will adjust to the massive increase in the cost of imported inputs, and the increase will reduce real wages (that, by the way, is one of the main reasons for the measure), and have a contractionary effect on spending, that will be compounded by the fiscal adjustment.

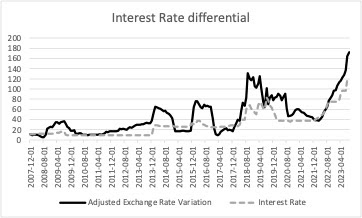

Two brief technical things. The adjustment may not per se improve the fiscal accounts, since the economic collapse will reduce revenue too. It is a well-known rule that consolidations (reductions of debt and of deficits, the results of policies) tend to be more successful with a growing economy, and without a massive adjustment (reduction in spending and/or higher taxes, the direct policies).* Second, the reduction in the exchange rate premium (the gap between official and parallel rates) is not an indication that things are better, if it is done, as it was, by depreciating massively the official rate. In particular, the question is what will happen with the parallel premium in the near future. The official exchange rate will be on a crawling peg, if the announcement of the new minister is believable. And the premium has been very high, because of the interest rate differential between returns in pesos and in dollars, adjusted for risk (see figure below, which shows the interest rate in pesos compared to the actual depreciation of the currency, plus the US rate and the EMBI from JP Morgan). The remuneration in dollars is always higher.

The government has also announced a plan to essentially transform the central bank bonds (Leliqs) into treasury bonds. And the interest rate on the central bank bonds were kept low, presumably to get everybody into the treasury ones. However, the treasury bonds will have to pay a very high rate, since the the expected depreciation is large, and the government announced it will continue. That suggests that they are expecting people to continue to go to dollars, and that might actually lead to a persistence or increase of the exchange rate premium. In particular, if there is significant wage resistance, to be expected after this massive depreciation, and inflation accelerates.

In the absence of dollars, there is little chance of a stabilization. The government may very well be trying to accelerate inflation to create the conditions for a dollarization later on.

* Most economists confuse adjustment and consolidation of fiscal accounts. In part to cloud the fact that consolidation does not require adjustment. The US reduced its massive debt accumulation during World War II, without adjustment, by growing fast in the post-war era, in which the government did run deficits frequently and the welfare state was actually expanded, particularly in the 1960s.

Wages and Inflation: Let Workers Alone

[Note: this is a slightly edited ChatGPT translation of an article for the Italian daily Domani]

Last week’s piece of news is the gap that opened between the US central bank, the Fed, and the European and British central banks. Apparently, the three institutions have adopted the same strategy, deciding to leave interest rates unchanged, in the face of falling inflation and a slowdown in the economy. But, for central banks, what you say is just as important as what you do; and while the Fed has announced that in the coming months (barring surprises, of course) it will begin to loosen the reins, reducing its interest rate, the Bank of England and the ECB have refused to announce cuts anytime soon.

To understand why the ECB remains hawkish, one can read the interview with the Financial Times of the governor of the Central Bank of Belgium, Pierre Wunsch, one of the hardliners within the ECB Council. Wunsch argues that, while inflation data is good (it is also worth noting that, as many have been saying for months, inflation continues to fall faster than forecasters expect), wage dynamics are a cause for concern. In the Eurozone, in fact, these rose by 5.3% in the third quarter of 2023, the highest pace in the last ten years. The Belgian Governor mentions the risk that this increase in wages will weigh on the costs of companies, inducing them to raise prices and triggering further wage demands; As long as wage growth is not under control, Wunsch concludes, the brakes must be kept on. Once again, the restrictive stance is justified by the risk of a price-wage spiral, that so far never materialized, despite having been evoked by the partisans of rate increases since 2021. Those who, like Wunsch, fear the wage-price spiral, cite the experience of the 1970s, when the wage surge had effectively fueled progressively out-of-control inflation. The comparison seems apt at first glance, given that in both cases it was an external shock (energy) that triggered the price increase. But, in fact, it was not necessary to wait for inflation to fall to understand that the risk of a wage-price spiral was overestimated and used by many as an instrument. Compared to the 1970s, in fact, many things have changed. I talk about this in detail in Oltre le Banche Centrali, recently published by Luiss University Press (in Italian): Automatic indexation mechanisms have been abolished, the bargaining power of trade unions has greatly diminished and, in general, the precarization of work has reduced the ability of workers to carry out their demands. For these and other reasons, the correlation between prices and wages has been greatly reduced over three decades.

But the 1970s are actually the exception, not the norm. A recent study by researchers at the International Monetary Fund looks at historical experience and shows that, in the past, inflationary flare-ups have generally been followed with a delay by wages. These tend to change more slowly than prices, so that an increase in inflation is not followed by an immediate adjustment in wages and initially there is a reduction in the real wage (the wage adjusted for the cost of living). When, in the medium term, wages finally catch up with prices, the real wage returns to the equilibrium level, aligned with productivity growth. If the same thing were to happen at this juncture, the IMF researchers believe, we should not only expect, but actually hope for nominal wage growth to continue to be strong for some time in the future, now that inflation has returned to reasonable levels: looking at the data published by Eurostat, we observe that for the eurozone, prices increased by 18.5% from the third quarter of 2020 to the third quarter of 2023, while wage growth stopped at 10.5%. Real wages, therefore, the measure of purchasing power, fell by 8.2%. Italy stands out: it has seen a similar evolution of prices (+18.9%), but an almost stagnation of wages (+5.8%), with the result that purchasing power has collapsed by 13%.

Things are worse than these numbers show. First, for convergence to be considered accomplished, real wages will have to increase beyond the 2021 levels. In countries where productivity has grown in recent years, the new equilibrium level of real wages will be higher. Second, even when wages have realigned with productivity growth, there will remain a gap to fill. During the current transition period, when real wages are below the equilibrium level, workers are enduring a loss of income that will not be compensated for (unless the real wage grows more than productivity for some time). From this point of view, therefore, it is important not only that the gap between prices and wages is closed, but that this happens as quickly as possible.

In short, contrary to what many (more or less in good faith) claim, the fact that at the moment wages are growing more than prices is not the beginning of a dangerous wage-price spiral and the indicator of a return of inflation; rather, it is the foreseeable second phase of a process of rebalancing that, as the IMF researchers point out, is not only normal but also necessary.

The conclusion deserves to be emphasized as clearly as possible: if the ECB or national governments tried to limit wage growth with restrictive policies, they would not only act against the interests of those who paid the highest price for the inflationary shock. But, in a self-defeating way, they would prevent the adjustment from being completed and delay putting once and for all the inflationary shock behind us.

The parallel universe in Japan continues and is delivering superior outcomes, while the rest look on clueless

It’s Wednesday and I have some commitments in Melbourne (recording a podcast with the Inside Network) and that requires some travel. So time is tight. Today, I update the latest from Japan courtesy of yesterday’s release from the Bank of Japan of its ‘Statement on Monetary Policy’. The parallel universe continues and is delivering superior…

Central banks and climate change

Today, I discuss a recent paper from the Bank of Japan’s Research and Studies series that focused on how much attention central banks around the world give to climate change and sustainability and how they interpret those challenges within their policy frameworks. The interesting result is that when there is an explicit mandate given to…

Inflation falling sharply in Australia while the RBA still is out there threatening rate rises

Yesterday (November 29, 2023), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest – Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator – for October 2023, which showed a sharp drop in inflation. This release resolves some of the uncertainty that arose when the September-quarter data came out last month, which showed a slight uptick. I analysed that…

Australia – stronger nominal wages growth but still below the inflation rate – no justification for deliberately increasing unemployment

Last week (November 15, 2023), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Wage Price Index, Australia – for the September-quarter 2023, which shows that the aggregate wage index rose by 1.3 per cent over the quarter (up 0.5 points) and 4 per cent over the 12 months (up 0.3 points). The ABS noted…