Inflation

Comments On Asset Prices And Inflation Targeting

This is an unedited manuscript excerpt, from a chapter that discusses how asset price changes relate to inflation.

This is an unedited manuscript excerpt, from a chapter that discusses how asset price changes relate to inflation.

Even if one believes that asset price increases represent inflation, the general reaction among North American central bankers would be to think you are crazy if you think asset prices should be included within an inflation target mandate. (I am less sure about the reaction of Continental European central bankers.) Although they might accept that exuberance in financial markets should be toned down, targeting asset prices directly poses many problems.

Embedded in this reaction is the conventional belief that raising the policy rate tends to slow inflation, while cutting them tends to raise the inflation. I must note that many proponents of Modern Monetary Theory disagree with that conventional belief – but explaining that divergence is out of the scope of this book. (It is explained in my book Modern Monetary Theory and the Recovery.) For simplicity, I will accept the conventional view here.

(One related problem is that if interest rates directly feed into inflation, then inflation will rise if the central bank hikes rates. This conflicts with the conventional view. As such, the Bank of England stripped the mortgage interest component out of the Retail Price Index.)

If we just look asset prices, we see two major problems with having them show directly up inside the inflation measure used in the inflation target. Firstly, financial asset prices are quite volatile relative to most consumer prices. Secondly, there is no way of targeting risk asset prices without blowing up the economy. (Although bonds are a financial asset, it is easy for the central bank to stop their prices from changing – they can peg interest rates along the curve. This idea sends most conventional economists straight to the fainting couch, it has been done historically (such as in the Second World War in the United States, and more recently, Japan). However, locking interest rates in this way largely eliminates flexibility in setting interest rates, which is conventionally believed to be necessary for inflation targeting.)

Equity prices go up and down much faster than the business cycle. If the central bank targeted them directly, they would end up cutting and hiking rates multiple times within a business cycle, which is presumed to destabilise the economy. Furthermore, equity prices may react to central bank movements. For example, imagine that equity prices are rising too rapidly. The central bank then hikes rates to counter this. Imagine then that equity holders panic, and prices collapse. What is the central bank supposed to do – cut rates again? (This is obvious to anyone other than the people who pin the blame for their inaccurate equity forecasts on the central bank, which is remarkably common among people who tend to be wrong about equity markets.)

Rapid interest rate movements by the central bank are going to spook borrowers and lenders. Markets would likely build in large risk premia, and pretty much everyone would start sourcing finance in other markets.

Even targeting slow-moving house prices poses dangers. To the extent that house prices reflect long-term interest rates, rising house prices are a side effect of a low interest rate environment. That environment is typically the result of the central attempting to avoid a recession when economic growth is sluggish. Hiking rates to target house prices is runs exactly counter to the desire to boost growth. Meanwhile, interest rates are not the only thing affecting house prices. Idiotic decisions in other spheres of policymaking can generate a housing boom or bust. Finally, the housing market is like any market run by humans – it has mood swings. The housing market may remain impervious to rate hikes for some time – until there is a panic that precipitates a collapse. Given the importance of residential investment within the economy, and the risks posed by widespread mortgage defaults, housing busts generally trigger ugly recessions.

My view is that the belief that central banks can easily target asset prices comes from an extremely dubious analogy to the Gold Standard – where the gold price was pegged. However, the reasons why the Gold Standard functioned no longer apply to any financial asset.

· Once international financial capitalism developed, the Gold Standard is best seen as a currency peg system. What mattered economically was the fixed exchange rates between the major economies. Gold was just the mechanism to adjust for capital flows across currencies. No financial asset can replace this at present -even gold. Unilaterally pegging your currency to a risk asset like gold is not going to change much. If your economy is large, you are just running a price control scheme for one financial asset – which other actors will attempt to exploit. If your economy is small, your exchange rate will fluctuate wildly based on speculation in some other market.

-

The political establishment built its world view around being willing to make sacrifices to restore previous exchange rates. However, only a small handful of people think this is a good idea, and so pegs lack political credibility.

-

Gold is a collectible that generates no cash flow, and its consumption by industry is largely insignificant when compared to existing above-ground inventories. Other assets either have cash flows that need to be priced or are commodities with relatively small inventories. There is no way for them to credibly have constant prices in a dynamic economy.

-

Earlier generations of financial market participants had an ideological belief that the gold peg system was credible. Modern market participants will speculate against any peg arrangement. The problem with defending pegs is that attacking them is a low-risk investment (since the price is largely locked) with a high potential pay off if the peg breaks.

If risk asset market prices reacted in a predictable fashion to the policy rate, it should be easy to generate models that generate massive profits by inputting market-expectations for the policy rate – which are decent over short horizons (outside crises). Such models are noticeably small on the ground. Although people (including myself) enjoy giving central bankers a hard time, most of the sensible ones have come to terms with that observation.

Email subscription: Go to https://bondeconomics.substack.com/

(c) Brian Romanchuk 2024

Markup matters: monetary policy works through aspirations

Tim Willems and Rick van der Ploeg

Since the post-Covid rise in inflation has been accompanied by strong wage growth, interactions between wage and price-setters, each wishing to attain a certain markup, have regained prominence. In our recently published Staff Working Paper, we ask how monetary policy should be conducted amid, what has been referred to as, a ‘battle of the markups’. We find that countercyclicality in aspired price markups (‘sellers’ inflation’) calls for more dovish monetary policy. Empirically, we however find markups to be procyclical for most countries, in which case tighter monetary policy is the appropriate response to above-target inflation.

In a simplified setup where wages are firms’ only input cost, while consumers only buy domestically produced goods, the ‘battle of the markups’ takes an intuitive form (Rowthorn (1977)):

- Workers aspire to have their nominal wage

feature a certain excess, typically referred to as the ‘wage markup’ (

) over the cost of their consumption basket

. This is equivalent to saying that their aspired real wage

equals

.

- Firms aspire to set their price

to secure a price markup ‘

’ over their marginal cost of production, which is the nominal wage rate

. That is: they aspire for

, implying that the real wage

desired by firms equal to

.

By itself, there is nothing guaranteeing that real-wage aspirations held by workers and firms are mutually consistent in this framework – ie, there is nothing to ensure that =

(Blanchard (1986); Lorenzoni and Werning (2023)). Every time that workers get to reset their wage, they may consider the prevailing real wage too low, upping the nominal wage. When firms next get to reset prices, they may consider the current real wage too high, upping prices. This could give rise to unstable wage-price dynamics.

Unemployment as an equilibrating device

Layard and Nickell (1986) argued that the moderating effect from the presence of unemployment acts like a clearing mechanism. They posed that aspired markups and

are likely cyclically sensitive. Workers might feel that they have less bargaining power when unemployment ‘

’ is higher, making them settle for a lower wage markup. Unemployment can thus act to tame unrealistic aspirations. Formally, this can be captured by modelling the aspired wage markup

as consisting of a structural component (‘

’) alongside a cyclically sensitive one (‘

’):

(1)

Here, the structural component ‘’ captures workers’ aspirations based on ‘exogenous’ factors, eg what they have gotten used to given their past consumption patterns. If

, the cyclical term ‘

’ captures the notion that workers’ aspired markups are procyclical, so that workers are likely to ‘settle for less’ when the threat of unemployment is greater.

Similarly, price markups aspired by firms also consist of a structural component alongside a cyclically sensitive one:

(2)

When it comes to the cyclicality of price markups, it is debated whether they are pro or countercyclical. On the one hand, a slowdown makes firms afraid of having to carry large inventories or suffer from capacity underutilisation. This would imply that aspired price markups are procyclical (). On the other hand, other theories imply that firms’ aspired markups move countercyclically (

). For example, by pushing some firms out of business, a recession may increase the market power of surviving firms – implying that firms’ aspired markups rise in downturns.

In general, and irrespective of the sign of , it is possible to find an equilibrium rate of unemployment, ensuring consistency between the real wage aspired by workers and that aspired by firms. At this point the wage-price cycle is put to rest – enabling inflation to land at target.

It can be shown that the equilibrium level of unemployment increases in structural aspirations held by workers and firms (): when workers and/or firms aspire to obtain a greater size of the pie, without the pie having grown in size, something will have to give. Here, that is unemployment which has the effect of moderating the elevated aspirations, to re-establish consistency. If unemployment does not rise to tame aspirations, there will be pressure on inflation in the short run. This is what has been called conflict inflation.

The role of the central bank

The story so far assumes that, somehow, the unemployment rate ‘agrees’ to clear any conflict between firms and workers. In reality, it won’t automatically. There are many reasons for unemployment to exist, eg search frictions (Pissarides (2000)) or providing incentives to limit shirking (Shapiro and Stiglitz (1984)). This implies that the level of unemployment is not ‘free’ to clear any conflict and further action is required.

This is where the central bank comes in. Through its mandate, the central bank is tasked with setting policy to keep inflation at target. In our framework, this implies that the central bank will attempt to set its policy to ensure that cyclical conditions are such that markup aspirations are consistent with the size of national income. And if aspired markups are cyclically sensitive, there is an ‘aspirational channel’ of monetary policy transmission.

If aspired markups of both firms and workers are procyclical (), the policy prescription for the central bank is conventional: it should tighten in response to inflationary pressures, as doing so will lower aggregate markup aspirations – eventually re-establishing consistency, which brings inflation back to target.

There is however debate over the sign of , with many studies arguing that firms’ aspired markups are, in fact, countercyclical (

), for example because more bankruptcies in recessions increase market power of surviving firms. Any resulting price increases can then be seen as a form of ‘sellers’ inflation’ (Weber and Wasner (2023)). In that case, policy prescriptions are less clear: even if a monetary tightening reduces workers’ aspired markups, it may not be successful in lowering inflation if the ensuing recession ends up increasing markups aspired by firms. On balance, inflation might thus increase following tighter monetary policy, and a more ‘dovish’ monetary policy would be called for – particularly if the channel via the Phillips curve (a monetary tightening lowering firms’ marginal costs) is weak.

Consequently, it is important for central banks to know whether firms’ aspired markups are pro or countercyclical. We have estimated the cyclicality of the price markup () for 61 countries (details are in our Staff Working Paper), and find that price markups are procyclical in most, including the UK and the US, but countercyclical in various other countries (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Estimated degree of cyclicality in price markups () in various countries

Paying for imports

Recent UK experiences have been more involved than the stylised situation described thus far. Next to domestic workers and firms, foreign exporters also lay a claim on UK output – as output is partly produced with imports, like energy. As energy prices rose around Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the UK’s terms-of-trade worsened and the share of national income flowing abroad suddenly went up – leaving less pie to be distributed domestically.

Absent any reduction in the structural components of markups aspired by firms and workers ( and

), a larger share of national income flowing abroad implies distributional conflict domestically – pushing inflation away from target. Since price markups are estimated to be procyclical in the UK (Chart 1), while the same is thought to apply to workers’ aspired wage markups, a rise in inflation may require the central bank to tighten. This is needed to moderate markup aspirations, ultimately clearing any conflict, enabling inflation to return to target.

Indeed, central bankers appear to have an ‘aspirational’ transmission mechanism in mind as can be seen from Christine Lagarde (2023):

We need to ensure that firms absorb rising labour costs in margins (…) The economy can achieve disinflation overall while real wages recover some of their losses. But this hinges on our policy dampening demand for some time so that firms cannot continue to display the pricing behaviour we have recently seen (emphasis added).

Conclusions and policy implications

A monetary tightening is not the only way via which markup aspirations could be moderated. Faced with an adverse terms-of-trade shock, it is also possible that workers and/or firms internalise the implications (that there is less income to be divided domestically), inducing them to lower the structural components of their aspired markups ( and

). In this regard, it would be interesting to obtain a better understanding as to whether communication (by central banks or governments) can ‘endogenise’ aspirations of workers and firms (making them directly sensitive to the terms-of-trade), as it is ultimately costly for a central bank to have to step in and tame aspired markups by affecting the business cycle.

Absent such a co-ordinated response, bringing inflation back to target following an adverse terms-of-trade shock may require a cyclical slowdown to moderate markups aspired by workers and firms. An important caveat is that this strategy might not work if firms’ aspired price markups are countercyclical, but we find no evidence for this in the UK. As a result, the monetary tightening implemented in recent years is likely to aid the disinflation process via our ‘aspirational channel’ (not present in most standard models, featuring acyclical desired markups), which facilitates inflation returning to target.

Tim Willems works in the Bank’s Structural Economics Division and Rick van der Ploeg is a Professor at the University of Oxford.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Inflation excluding volatile items is now falling back to around 2 per cent in Australia – despite the efforts of the RBA

Today (March 27, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest – Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator – for February 2024, which showed that the annual inflation rate steadied at 3.4 per cent. Today’s figures are the closest we have to what is actually going on at the moment and show many of…

“Wish I Was Rich Enough To Eat Like A 17thC Flemish Peasant” Thinks Man Staring In Artisanal Bakery Window

A Sydney man staring idly at the pricey wares on offer in an Eastern Suburbs artisanal bakery is currently wishing that he was wealthy enough to afford to eat like a subsistence farmer from the Renaissance.

“You must have had to have made a fortune in the tulip craze to find room in your budget for a boulot sourdough loaf and a raisin snail,” mused Gymea electrician Phil Walker as he tossed up whether to enter the establishment to pick up a few things for dinner. “I’m guessing it must cost a shitload to put an unnecessary dusting of flour on everything and display them all in small wicker baskets.”

“I never knew that grim faced serfs who only got one half a day off every year for Easter cared so much about fine crumb structure and single origin grain,” pondered Walker as he read the hand written label on a basket of New York rye. “That guy behind the counter in the apron with the beard, tribal tatts and nose rings looks like he just stepped straight out of a painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder.”

Unable to justify parting with $11.50 for a loaf of harvest grain lovingly crafted from a gritty mixture of millet, rat’s teeth, bark and plague germs, Phil has opted to get a six pack of Tip Top white hamburger buns from Woolies.

Peter Green

http://www.twitter.com/Greeny_Peter

You can follow The (un)Australian on twitter @TheUnOz or like us on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/theunoz.

We’re also on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/theunoz

The (un)Australian Live At The Newsagency Recorded live, to purchase click here:

Bank of Japan’s rate rise is not a sign of a radical policy shift

Yesterday, the Bank of Japan increased its policy target rate for the first time in 17 odd years and it set the noise level among the commentariat off the charts – ‘finally, they have bowed to the pressure from the financial markets’, ‘major tightening’, ‘scraps radical policy’, etc – all the hysteria. The reality is…

Macro N Cheese Podcast - Inflation

I was recently on a podcast with Steven D. Grumbine to discuss inflation. Link: https://realprogressives.org/podcast_episode/episode-268-there-is-no-magic-pricing-fairy-with-brian-romanchuk

The podcast description from the webpage is.

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Milton Friedman

This quote by the grandaddy of neoliberal economics is from 1963. Some in the mainstream have been dining out on it ever since.

According to our guest, author and blogger Brian Romanchuk, neoclassical economics relies on mathematical models and fail to capture the complexity of real-world inflation. He highlights the importance of understanding the supply and demand dynamics in setting prices and explains that inflation can be influenced by factors such as supply chain shocks and changes in the labor market.

Brian also points out that it’s not enough to blame inflation on corporate greed; after all, corporations are always driven to maximize profits. He mentions the Cantillon effect, which suggests that the first recipients of newly created money benefit from inflation as prices go up, while the poor and working class bear the brunt of higher prices down the road.

Brian and Steve discuss inflation constraints on fiscal policy. Brian argues that while extreme fiscal policies could lead to inflation, most of the time, fiscal policy is relatively moderate and does not have a significant impact on inflation. They criticize the government for not trying to set prices and argue that the government often follows the private sector’s lead, making things worse.

This is a discussion of some topics around inflation. Although some of the discussion related to the concerns of my book, a lot of it relates to some of the recent political economy controversies with inflation. It was fun, although I am not sure how well suited I am to the podcast format.

Otherwise, I have been plugging away at fixing weak points in my inflation manuscript. Rather than waste reader’s time by rushing out some random comment, you are encouraged to get your dose of Romanchuk (and Grumbine) content via the podcast.

Email subscription: Go to https://bondeconomics.substack.com/

(c) Brian Romanchuk 2024

Debt, Deficits, and Warranted Money

by Brian Czech

Concern over mushrooming debt is growing. Click on the image to see the casino-like tumbling of national debt “clocks.” (US Debt Clock)

If you recognize the damages done by a bloating economy, you’ll be alarmed by the global GDP meter, which hit the existentially menacing threshold of $100 trillion in 2022. If that doesn’t give you a dose of distress, try the global debt clock. Then, for a dizzying dose indeed, check the casino-like combination of debt and GDP maintained by “US Debt Clock.”

Almost all readers, bearish and bullish alike, can sense the unsustainability of skyrocketing debt. Even wild-eyed growthists, who see no problem in a perpetually growing GDP, can’t abide a perpetually growing debt. Yet very few critics of debt can articulate, with economic fundamentals, why such debt is so unsustainable.

Sadly absent from the discussion of debt is the ecological underpinnings of money. As long as these underpinnings remain overlooked, the money lenders will be overbooked. Deficit spending will rule the day, and global debt will continue rocketing into the stratosphere, heading for the sun like a pecuniary phoenix.

Let’s have a closer look at the debt problem, with a focus on global and U.S. scenarios. We’ll consider the relationship of debt to deficit spending, along with inflation. Finally, we’ll bring in the ecological basis of money, and hope our policymakers grasp and apply it, lest our money supply—not to mention the planet—turn to ashes.

Deficits and Debt: Global and U.S.

As global GDP was ramping up to the planetarily punishing $100 trillion level, global debt was already surpassing $300 trillion. It reached that dubious distinction in 2021, just one year after reaching the previous record of $226 trillion. It has since come down from the peak, but still stands around $238 billion, and the reduction is surely short-lived.

The majority of global debt is private, especially corporate but significantly household debt as well. Public debt—money owed by governments—makes up about a third.

In the USA, those proportions are roughly reversed. From the county commission to Capitol Hill, American politicians have ambitions that far exceed government coffers. When they’re not spending money to “stimulate the economy,” they’re trying to spend their way out of the social and environmental problems caused by an overstimulated economy. They spend money they don’t have; that’s deficit spending and it adds to the public debt.

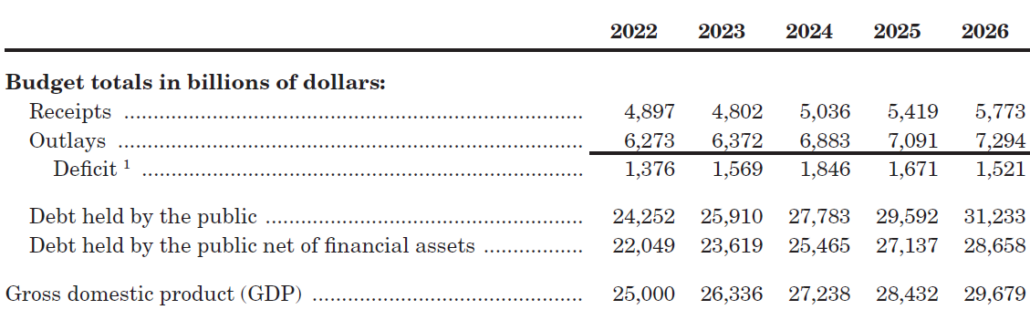

Deficit spending is a way of political life in the U.S. Government. (Image snipped from 2024 Budget of the U.S. Government.)

At this point in fiscal year 2024 (October 1, 2023 through September 30, 2024), the U.S. government deficit stands at roughly $532 billion, contributing another two percent to the federal debt of $26 trillion. The deficit may lessen as taxes are collected in the coming months, but then it will shoot back up for the remainder of the year. Even the figures provided by the Administration (probably rosy figures) acknowledge that the deficit is expected to be a whopping $1.8 trillion by the end of fiscal 2024. That’s nearly seven percent of the 2023 GDP ($26 trillion).

The USA is particularly relevant to the global debt; its debt is bigger than any other. In fact, U.S. entities—government and private combined—carry a debt burden nearly the size of the global economy!

Only Japan and China have joined the USA in the club of over $10 trillion government debt. France, Italy, the UK, Germany, India, Canada, Spain, and Brazil all have debts exceeding a trillion dollars.

In terms of relative debt (ratio of debt to GDP), Japan is at the top of the list at 255 percent. Greece, Singapore, Italy, Bhutan, and the USA (123 percent) round out the top six.

Deficit Spending: Getting Dumb and Dumber?

Deficit spending has a long history in American policy. The fiscal exigencies of war have triggered deep deficits, with World War II as the classic case. But huge deficits were already incurred during the Great Depression, coinciding with the influence of the British economist John Maynard Keynes. In the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes prescribed a liberal dose of deficit spending to spur the western economies out of recession.

But Keynes never said to go hog wild, much less stay that way. So, for many decades now Americans have heard the debate between fiscal conservatives and “deficit-spending liberals.” They both want growth, but conservatives think a persistent deficit and ballooning debt is more burden than boon for GDP. They typically only abide a big debt for hawkish military purposes. Otherwise they’re “budget hawks.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are you sure about MMT? (Wikipedia)

Inveterate deficit spenders, on the other hand, think they can stimulate the economy by picking the winners and funding the right programs.

Into this old debate comes “modern monetary theory,” centered around the idea that deficit spending is generally fine, and policymakers needn’t worry too much about a growing debt, as long as the economy is also growing. Beyond that, “MMT” seems to mean many things to many people and has polarized the economics community. Even pollyannish growthists like Paul Krugman find MMT “obviously indefensible.” Another growthist (aren’t they all?) at the dark-monied Mercatus Center calls MMT “a bizarre, illogical, convoluted way of thinking.”

MMT does, however, provide some political cover for politicians hunting pork. The late King of Pork, Senator Robert Byrd, would have championed MMT all the way to the bottom line. But MMT has persuaded some presumably more fiscally innocent members of Congress, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Senator Bernie Sanders, and even John Yarmuth, past chair of the House Budget Committee.

In any event, it’s hard to tell what’s so “modern” about MMT. It has a few new wrinkles—it picks them up as it goes along—but basically it’s just another phase of Keynesian thought on deficit spending. And, as President Nixon said a half century ago, “We’re all Keynesians now.” He could have added, “We’re all growthists, too!”

And so, the first subheading that appears in this year’s federal budget (page 5) is: “GROWING THE ECONOMY FROM THE BOTTOM UP AND MIDDLE OUT.” We could add: “WITH A SHOT OF DEFICIT STEROIDS.”

Money Supplies: Warranted vs. Inflated

In 1939, one Sir Roy Forbes Harrod wrote “An Essay in Dynamic Theory,” published in the stately Economic Journal. Until then, little had been theorized about the process of economic growth, and rarely with such nuance. Harrod’s approach is considered a leading precedent of growth theory.

Harrod spent much of his 20-page essay contemplating three kinds of growth rates: warranted, natural, and actual. Our charge here is not to dive deeply into Harrod’s thoughts on growth rates, but to see where they take us on debt and inflation. In particular, I propose we have three levels of money supply: warranted, real, and nominal.

Economists are familiar with the latter two. The real money supply has been adjusted for inflation, typically by pegging to a particular year. The nominal supply is expressed in terms of face value in real time. For example, $1.38 trillion today—the nominal money supply of a hypothetical country—is only one trillion real dollars, if we’re pegging to 2010.

It’s the “warranted” supply I’m proposing here. The concept stems from the trophic theory of money, which is that money originates via the agricultural surplus at the base of the economy. Not agricultural surplus in the sense of grain going to waste in the fields, but surplus in the sense that one farmer can grow enough to feed many people.

It is that surplus—more broadly, a food surplus but for all practical purposes the agricultural surplus—that frees the hands for the division of labor. The division of labor, in turn, allows for the exchanging of goods and services. All this calls for an efficient means of exchange, store of value, and unit of account: money, in other words.

Money is warranted, then, by the division of labor flowing from agricultural surplus.

Money didn’t just originate historically via agricultural surplus—as it did in Mesopotamia, Lydia, and the Yellow River Basin of China—it originates each year in the breadbaskets of the world. Actually it originates twice a year as these breadbaskets are found in Northern and Southern Hemispheres. North America (prairies and California), China, Southeast Asia, Brazil, and Chile come to mind, plus of course the contested confluence of political Europe and Russia, centered in Ukraine.

You might say money gets “printed” into circulation with each perennial pulse of wheat, rice, corn, oats, barley, and soybeans. Massive harvests free billions of hands for a spectacular division of labor and the exchanging of trillions of dollars of warranted money. Lenin was right on the money (so to speak) when he referred to grain as “the currency of currencies.”

Wheat combine “printing money” in North Dakota. (Flickr)

Think about it: How would money remain relevant in a world of agricultural collapse? Everyone would be occupied with growing, gathering, catching, or commandeering their own food. No one would be producing other types of goods and services, much less bringing them to market. Money would be worthless; it wouldn’t be warranted.

Not so with the collapse of massage services, NASCAR, hip hop, or even Taylor Swift. Nor with the disappearance of boats, guns, electronics, fur coats, or perfumes. A thousand container ships of manufactured dreck could be dumped in the Panama Canal, never to be seen or sold again, and the economy would persist. Plenty of other goods and services would remain. Money would still be meaningful, relevant, and valuable.

It’s an entirely different story with the world’s soy, root crops, poultry, livestock, finfish, and, above all, grain. Burn those up like some omnipotent, omnipresent Putin, and watch the economy come tumbling down in days.

That is why, in a fundamental sense, it is agricultural surplus that “prints” money into circulation. The warranted money supply, then, is that which reflects the amount of agricultural surplus. Lots of surplus warrants lots of money; little surplus warrants little money.

The trophic theory of money doesn’t explain every possible aspect of monetary economics, at least not directly. For example, how big a role do livestock and fish play in food surplus and therefore warranted money? What’s the linkage of food surplus to energy inputs? What about other natural resources at the trophic base of the economy such as heavy fiber and timber? (It takes clothing and shelter to subsist, not just food.)

The trophic theory of money generates plenty of research questions, but it provides plenty of insight as is. Take inflation, for example. That’s when the nominal money supply exceeds the warranted supply.

Limits to Warranted Money

While it is helpful to think of money as being “printed” into circulation with agricultural surplus, it is even more helpful to think of money being “footprinted” into circulation. There’s no way to produce an agricultural surplus—or a warranted money supply—without a heavy ecological footprint. Not for a population of eight billion people.

It takes a lot of inputs to grow a lot of food, so the ecological footprint of agriculture reaches far beyond the field. (Flickr)

Each parcel on the planet has a biological capacity. So, given limits to agricultural efficiency, we know that the ecological footprint of agriculture can only reach so far (or sink so deep, if you prefer). Then it exceeds the biological capacity, agricultural surplus plunges, and the warranted money supply drops like a shot.

The pre-existing, nominal money supply remains, but to what avail? With no agricultural surplus, businesses big and small disappear—banks, too—and the government defaults. All but the most civilized (or uncivilized but ethical?) polities descend into some sort of chaos. The nominal money supply might still be in the trillions of dollars, but it’s neither warranted nor real. It’s like the gold supply of King Midas. It’s hyperinflated, not because of an “overheated” economy and the pull of demand; quite the opposite. It’s devalued by “cost-push” inflation, the relentless price increases due to diminished stocks of natural capital.

What the Fed Needs Now

The Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, Budget Committee(s), World Bank, and all the other fiscal, monetary, and financial institutions need a reality check in the form of basic and applied ecology. They need to learn especially about the concepts of trophic levels and carrying capacity. Otherwise they won’t be able to sufficiently connect the dots among deficits, debt, and cost-push inflation.

Right now, the Fed’s approach to curbing inflation is the ham-handed raising of interest rates. But raising interest rates only works (sometimes) for the “demand-pull” form of inflation, where prices rise due to an increasing propensity to consume, or due to an injection of nominal money (as with deficit spending). It’s no remedy for cost-push inflation stemming from limits to growth in the real economy.

The Federal Reserve needs ecological training to manage inflation. (Wikipedia)

I’m not saying these accomplished folks—geniuses in other ways—have no sense of economic capacity. They most certainly do; they monitor and talk about it all the time. Unfortunately, they have essentially no knowledge of ecological capacity, so their notions of economic capacity are flawed. They tend to think of capacity in terms of financial capital, labor, manufacturing facilities, infrastructure, and new technology. It’s reminiscent of Herman Daly’s lament about focusing on the kitchen and the cook, with little thought to the ingredients.

When is the last time you heard a Jerome Powell or a Janet Yellen utter a word like “soil” or “water” or “forest” or “fishery”? Yet those are the stocks of natural capital at the very base—the trophic base—of the economy they preside over. They should be intent upon conserving those stocks, if not for purposes of long-term human wellbeing (which would be nice), then at least for purposes of fighting inflation!

Brian Czech is CASSE’s Executive Director.

The post Debt, Deficits, and Warranted Money appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Latest US inflation data is no cause for alarm – the trend is down

It’s Wednesday and I have looked at the US CPI release overnight that has set alarm bells off in the ‘financial markets’ and among mainstream economists. My assessment is that there is nothing much to see – annual inflation less volatile items is still falling and the lagged impact of shelter (housing) is still evident…

Atonella Stirarti's Godley-Tobin Lecture

Will the Moderation in Wage Growth Continue?

Wage growth has moderated notably following its post-pandemic surge, but it remains strong compared to the wage growth prevailing during the low-inflation pre-COVID years. Will the moderation continue, or will it stall? And what does it say about the current state of the labor market? In this post, we use our own measure of wage growth persistence – called Trend Wage Inflation (TWIn in short) – to look at these questions. Our main finding is that, after a rapid decline from 7 percent at its peak in late 2021 to around 5 percent in early 2023, TWin has changed little in recent months, indicating that the moderation in nominal wage growth may have stalled. We also show that our measure of trend wage inflation and labor market tightness comove very closely. Hence, the recent behavior of TWIn is consistent with a still-tight labor market.

TWIn: Measuring the Persistence of Wage Inflation

To recover the persistent (“core”) component of wage inflation, we rely on a framework that combines worker-level data with time series filtering techniques. Here, we briefly summarize the methodology. Additional details can be found in our previous Liberty Street Economics post and in this paper.

We start from monthly data on wage growth across seven different industries from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Following the well-established methodology of the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker, we define wage growth as the median percent change in the hourly wage of individuals observed twelve months apart. We then estimate a model in which wage growth in each industry is decomposed into the sum of a persistent component and a noise term that captures transitory variation and measurement error. Both persistent and noise components are further split into common and industry-specific terms to accommodate potential cross-sectional correlation.

Importantly, we estimate the persistence of unobserved monthly wage growth from year-over-year wage changes. Our measure therefore tends to lead year-over-year wage changes, which are influenced by wages in the past twelve months by construction. This produces a timely measure of wage growth, useful to detect turning points in real time.

Will Strong Wage Growth Last?

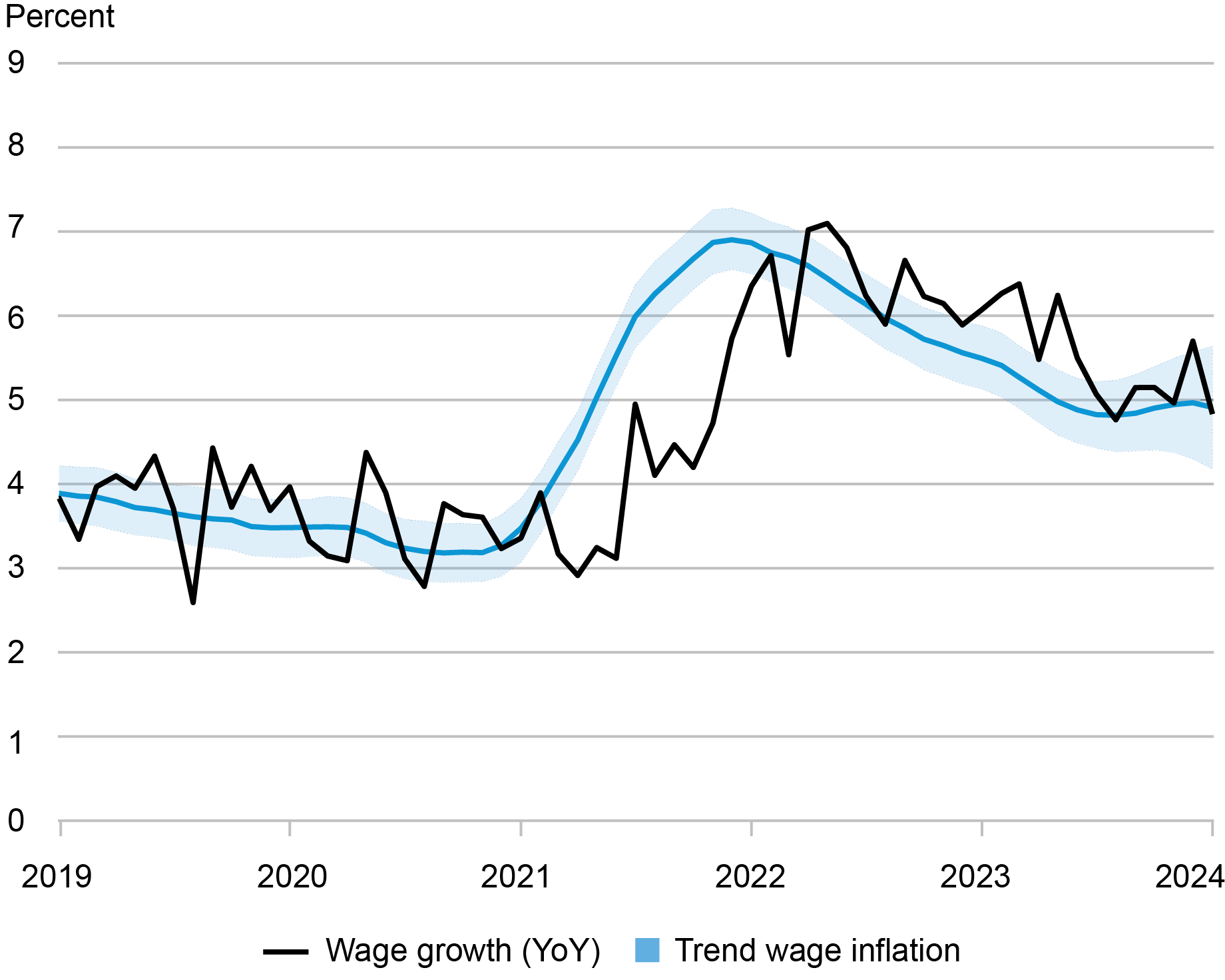

The chart below shows our estimated trend (solid blue line) together with the realized twelve-month wage growth defined as described above (black line). The shaded area around the trend is a 68 percent confidence band that captures the uncertainty associated with the estimates. We highlight two main takeaways.

Wage Growth as Measured by TWIn Peaked in Late 2021, Then Moderated

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

First, after remaining stable between 2019 and 2020, the trend increased markedly at the beginning of 2021, nearly doubling over the course of the year. As such, a large chunk of the wage growth we saw over the course of 2021 appears to have been persistent. It is worth stressing once more that the trend extracted by the model is expressed in terms of annualized monthly wage growth, which explains why it leads the actual year-over-year wage growth series in the chart.

Second, the model suggests that the trend may have peaked in the early months of 2022, and then started declining. The moderation in TWIn flattened out mid-2023 and has remained stagnant since. However, the shaded areas still illustrate considerable uncertainty. The recent slowdown estimated by our model indicates it cannot be ruled out that wage growth will continue to be markedly higher in the near-term than it was before the pandemic.

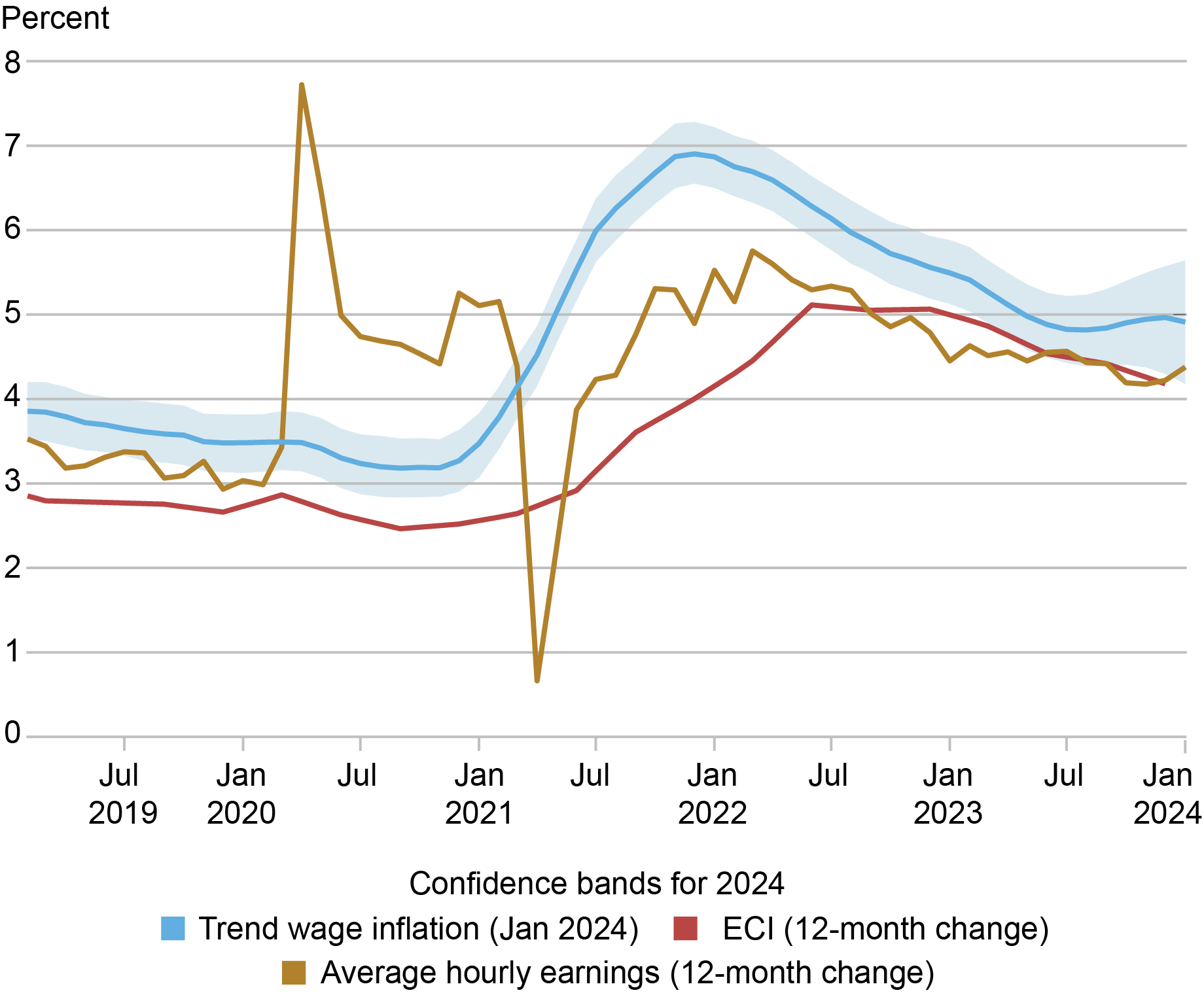

However, alternative indicators of wage growth have been sending mixed signals in recent months, as we show in the chart below. The employment cost index (ECI), shown in red, has been trending downward, though the most recent data point for this measure is for the last quarter of 2023. The deceleration in average hourly earnings has stalled recently and the growth rate even ticked up in January. Finally, as discussed, TWIn has been mostly flat in the last six months. These mixed signals reinforce the point on the uncertainty around our TWIn estimates moving forward.

Alternative Indicators of Wage Growth Are Sending Mixed Signals

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

Wage Growth Persistence as a Signal of the Labor Market

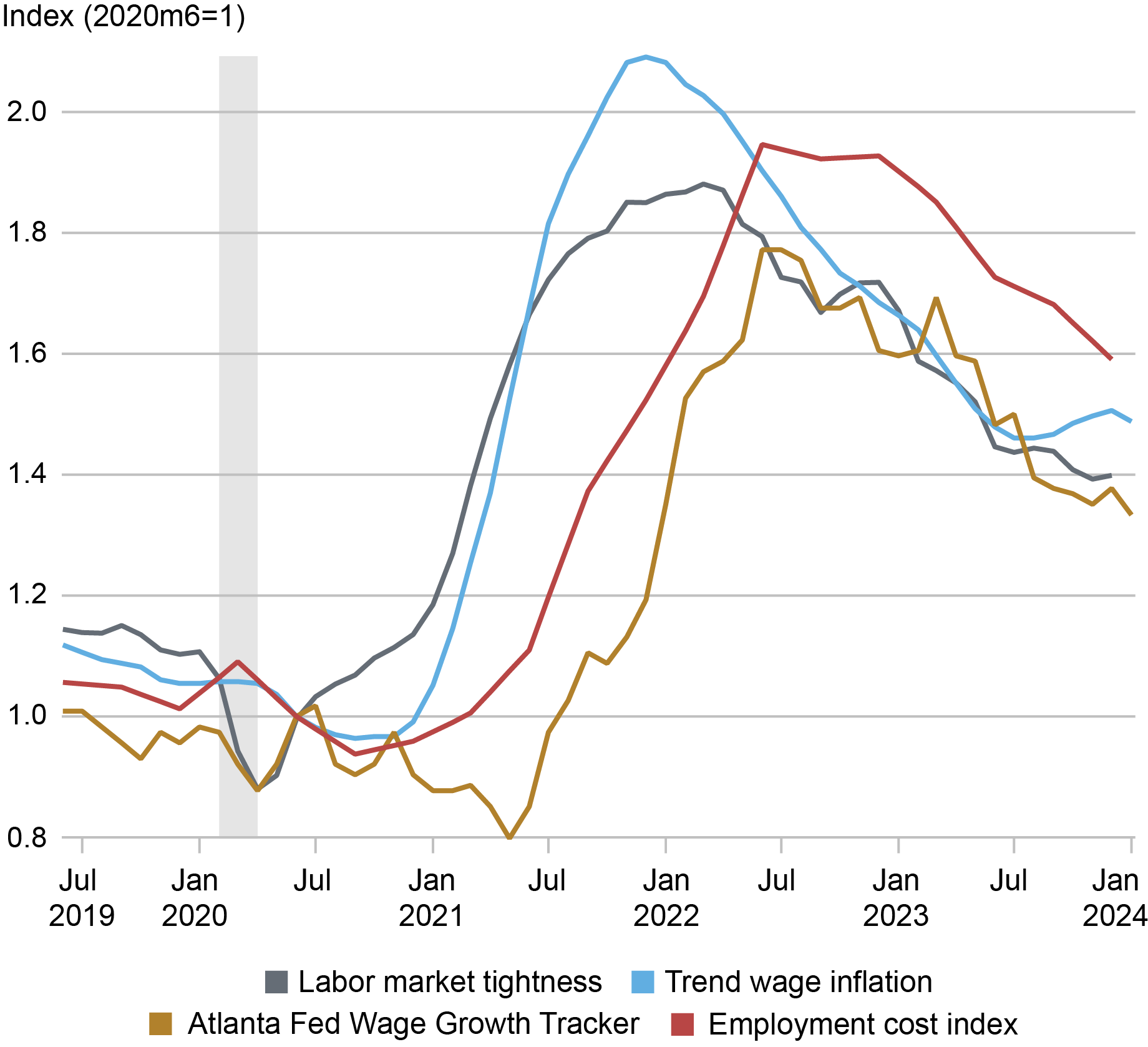

Our filtering approach to time aggregation delivers a measure of wage inflation that is timelier than alternatives. We show this in the chart below, which compares the recent evolution of our measure (blue), the employment cost index (red), and the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker (gold). Our measure of Trend Wage Inflation always leads alternative measures of wage growth: importantly, it is better aligned to labor market tightness. We illustrate this point in the chart where the grey line denotes labor market tightness, defined as job openings divided by the labor force.

TWIn and Labor Market Tightness Tend to Move in Tandem

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ estimates.

Our measure of Trend Wage Inflation therefore represents an additional signal on the current state of the labor market. When labor market conditions are tight – that is, when there are a lot of vacant jobs relative to job seekers – wage growth is high, as firms need to post higher wages to attract and retain workers. TWIn and labor market tightness both peaked toward the end of 2021. Thereafter, both measures have gradually fallen, as the imbalance between job openings and job seekers has gradually diminished.

What are the implications of persistent nominal wage growth? First and foremost, TWIn adds to other indicators pointing to a still-tight labor market. Many labor market indicators, such as job vacancies or the rate at which unemployed workers find jobs, are still at or above their pre-pandemic level. In addition, persistently elevated nominal wage growth may have repercussions for price inflation, although it may also be the result of wages in nominal terms catching up with previously high price inflation. Our approach offers a way to look under the hood of short-run, noisy fluctuations in wage growth. While considerable uncertainty remains, our estimates point to persistent wage growth that is still above its pre-pandemic levels.

Martín Almuzara is a research economist in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Audoly is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Augustin Belin is a research analyst in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Martin Almuzara, Richard Audoly, Augustin Belin, and Davide Melcangi, “Will the Moderation in Wage Growth Continue? ,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/03/will-the-moderatio....

A Turning Point in Wage Growth?

A Measure of Core Wage Inflation

Measuring Price Inflation and Growth in Economic Well‑Being with Income‑Dependent Preferences

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).