Inflation

Auto Loan Delinquency Revs Up as Car Prices Stress Budgets

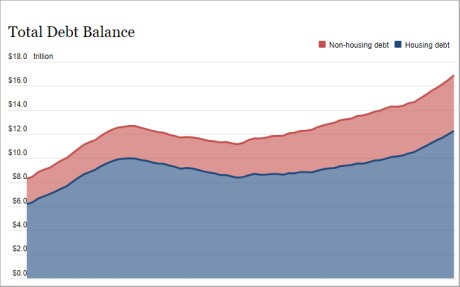

The New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data released the Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the fourth quarter of 2023 this morning. Household debt balances grew by $212 billion over the last quarter. Although there was growth across most loan types, it was moderate compared to the fourth-quarter changes seen in the past few years. Mortgage balances grew by $112 billion and home equity line of credit (HELOC) balances saw an $11 billion bump as borrowers tapped home equity in lieu of refinancing first mortgages. Credit card balances, which typically see substantial increases in the fourth quarter coinciding with holiday spending, grew by $50 billion, and are now 14.5 percent higher than in the fourth quarter of 2022. Auto loan balances saw a $12 billion increase from the previous quarter, continuing the steady growth that has been in place since 2011. In this post, we revisit our analysis on credit cards and examine which groups are struggling with their auto loan payments. The Quarterly Report and this analysis are based on the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (CCP), a panel which is drawn from Equifax credit reports.

Motor vehicles saw some of the most pronounced and persistent price increases during the pandemic inflationary episode, as supply chains and chip shortages limited production. During this spell, auto loan balances ballooned. The average origination amount—that is, the borrowing amount of a car loan—had crept up slowly between 2015 and 2020 at a pace of under one percent each year, reaching about $18,000 in the first quarter of 2020. But when car prices soared in 2021 and 2022, the average amount of newly originated auto loans jumped up as well, by 11 percent through 2021 and another 10 percent in 2022. By the end of 2022, the average origination amount on auto loans was nearly $24,000. In the last year, however, both prices and average auto loan origination amounts have begun to fall. The chart below shows how average auto loan origination amounts have tracked car prices, using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for new and used motor vehicles, in blue and red respectively, and the average origination amount, in gold.

Borrowing Amounts Loosely Track Car Price Changes

Percentage change in origination amounts since 2018:Q2

{"padding":{"auto":false,"left":25,"right":25},"data":{"groups":[],"labels":false,"type":"line","order":"desc","selection":{"enabled":false,"grouped":true,"multiple":true,"draggable":true},"xFormat":"%Y-%m-%d","x":"Date","rows":[["Date","CPI: New vehicles","CPI: Used cars and trucks","Mean origination amount for auto loans"],["2015-01-01","0","6","-4"],["2015-04-01","1","8","-9"],["2015-07-01","1","7","-2"],["2015-10-01","1","5","-3"],["2016-01-01","1","4","-1"],["2016-04-01","1","5","-8"],["2016-07-01","1","4","-1"],["2016-10-01","1","2","4"],["2017-01-01","2","1","1"],["2017-04-01","1","0","-3"],["2017-07-01","0","-1","1"],["2017-10-01","0","0","3"],["2018-01-01","1","0","2"],["2018-04-01","0","0","0"],["2018-07-01","0","0","3"],["2018-10-01","0","1","7"],["2019-01-01","2","1","5"],["2019-04-01","1","1","6"],["2019-07-01","0","2","9"],["2019-10-01","0","1","6"],["2020-01-01","2","0","12"],["2020-04-01","1","-1","12"],["2020-07-01","1","6","3"],["2020-10-01","2","12","20"],["2021-01-01","3","10","21"],["2021-04-01","4","31","25"],["2021-07-01","8","40","33"],["2021-10-01","13","48","37"],["2022-01-01","16","53","44"],["2022-04-01","17","50","47"],["2022-07-01","19","50","49"],["2022-10-01","21","43","32"],["2023-01-01","23","35","43"],["2023-04-01","23","42","40"],["2023-07-01","23","40","42"],["2023-10-01","23","37","40"]]},"axis":{"rotated":false,"x":{"show":true,"type":"timeseries","localtime":true,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":{"max":"0"},"fit":true,"outer":true,"multiline":false,"multilineMax":0,"rotate":0,"format":"%Y:$QQ","values":["2015-01-01","2021-01-01","2017-01-01","2019-01-01","2023-01-01"]},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-center"},"format":"%Y-%m-%d"},"y":{"show":true,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false},"padding":{"top":3,"bottom":0},"primary":"","secondary":"","label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"},"max":60,"min":-10},"y2":{"show":false,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"padding":{"top":3},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"}}},"chartLabel":"Percentage change in origination amounts since 2018:Q2","color":{"pattern":["#61AEE1","#B84645","#B1812C","#046C9D","#9FA1A8","#DCB56E"]},"interaction":{"enabled":true},"point":{"show":false},"legend":{"show":true,"position":"bottom"},"tooltip":{"show":true,"grouped":true},"grid":{"x":{"show":false,"lines":[],"type":"indexed","stroke":""},"y":{"show":true,"lines":[],"type":"linear","stroke":""}},"regions":[],"zoom":false,"subchart":false,"download":true,"downloadText":"Download chart","downloadName":"chart","trend":{"show":false,"label":"Trend"}}

Sources: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax; Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: CPI is Consumer Price Index.

Household debt delinquencies reached historic lows during the pandemic period, thanks to forbearances on mortgages and federal student loans and stimulus payments. But as forbearances ended and the savings from stimulus payments were exhausted for many households, delinquency rates have been rising again, for all types of debt. The chart below shows the percentage of auto balances newly transitioning to delinquency. Both auto loans and credit cards have seen particular worsening of new delinquencies, with transition rates now above pre-pandemic levels. [Note that the subsequent analysis uses a loan-level data set drawn from the Consumer Credit Panel by the Philadelphia Fed. While similar to the individual-level data used for the Quarterly Report, this alternative loan-level data permits finer analysis by vintage and loan origination amount. Due to some different inclusion criteria, aggregates from tradeline data may differ slightly from those in the Quarterly Report.]

Auto Loan Delinquency Transition Rates Surpass Pre-Pandemic Levels

Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency

{"padding":{"auto":false,"right":25,"left":25},"data":{"groups":[],"labels":false,"type":"line","order":"desc","selection":{"enabled":false,"grouped":true,"multiple":true,"draggable":true},"x":"Date","xFormat":"%Y-%m-%d","rows":[["Date","Delinquency"],["2017-06-01","2.01"],["2017-09-01","2.01"],["2017-12-01","1.89"],["2018-03-01","1.55"],["2018-06-01","1.88"],["2018-09-01","1.93"],["2018-12-01","1.93"],["2019-03-01","1.55"],["2019-06-01","1.75"],["2019-09-01","1.96"],["2019-12-01","1.87"],["2020-03-01","1.48"],["2020-06-01","1.13"],["2020-09-01","1.46"],["2020-12-01","1.56"],["2021-03-01","1.21"],["2021-06-01","1.09"],["2021-09-01","1.38"],["2021-12-01","1.50"],["2022-03-01","1.36"],["2022-06-01","1.59"],["2022-09-01","1.92"],["2022-12-01","1.91"],["2023-03-01","1.62"],["2023-06-01","2.02"],["2023-09-01","2.05"],["2023-12-01","2.24"]]},"legend":{"show":false,"position":"bottom"},"axis":{"rotated":false,"x":{"show":true,"type":"timeseries","localtime":true,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"fit":true,"outer":true,"multiline":false,"multilineMax":0,"format":"%Y:$QQ","values":["2019-01-01","2021-01-01","2023-01-01","2018-01-01","2020-01-01","2022-01-01"]},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-center"},"format":"%Y-%m-%d"},"y":{"show":true,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"values":["3.0","2.5","2.0","1.5","1.0","0","0.5"]},"padding":{"top":3,"bottom":0},"primary":"","secondary":"","label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"},"max":3,"min":0},"y2":{"show":false,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"padding":{"top":3},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"}}},"chartLabel":"Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency","color":{"pattern":["#61AEE1","#B84645","#B1812C","#046C9D","#9FA1A8","#DCB56E"]},"interaction":{"enabled":true},"point":{"show":false},"tooltip":{"show":true,"grouped":true},"grid":{"x":{"show":false,"lines":[],"type":"indexed","stroke":""},"y":{"show":true,"lines":[],"type":"linear","stroke":""}},"regions":[],"zoom":false,"subchart":false,"download":true,"downloadText":"Download chart","downloadName":"chart","trend":{"show":false,"label":"Trend"}}

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, using Philadelphia Fed auto loan tradeline data.

Note: The chart shows transition rates into 30-day delinquency and rates are balance-weighted.

Who Is Driving Up Delinquencies?

We now look at delinquency rates by various borrower traits. In the next chart, we examine delinquency by birth generation. Delinquency tends to decrease with age, and younger generations have delinquency rates slightly higher than their predecessors. In our recent post on credit cards, we saw that Millennials (born 1980-1994) have seen delinquency rates worsening more quickly than other generations. For auto loans, this appears to be the case as well, although the disparities here are less pronounced. All generations have delinquency transition rates that have been rising sharply over the past two years, with those for Millennials and Baby Boomers (born 1946-64) now being above their pre-pandemic levels. Note that the data in the next two charts, unlike the previous chart, is annualized using four-quarter moving sums to account for seasonal trends.

Delinquency Transition Rates for Baby Boomers and Millennials Are Now above Pre-Pandemic Levels

Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency

{"padding":{"auto":false,"right":18,"left":23},"data":{"groups":[],"labels":false,"type":"line","order":"desc","selection":{"enabled":false,"grouped":true,"multiple":true,"draggable":true},"x":"Date","rows":[["Date","Baby Boomers","Generation X","Millennials","Generation Z"],["2018-03-01","5.17","7.93","9.26","13.28"],["2018-06-01","4.85","7.70","9.42","13.02"],["2018-09-01","4.65","7.61","9.33","13.08"],["2018-12-01","4.66","7.69","9.28","13.19"],["2019-03-01","4.53","7.79","9.20","13.28"],["2019-06-01","4.54","7.48","8.94","13.07"],["2019-09-01","4.53","7.52","8.91","12.83"],["2019-12-01","4.50","7.34","8.90","12.32"],["2020-03-01","4.49","7.15","8.91","12.00"],["2020-06-01","4.08","6.59","8.09","10.37"],["2020-09-01","3.87","5.90","7.49","9.39"],["2020-12-01","3.76","5.49","7.11","8.90"],["2021-03-01","3.68","5.17","6.67","8.26"],["2021-06-01","3.68","4.89","6.81","8.20"],["2021-09-01","3.60","4.76","6.63","8.49"],["2021-12-01","3.43","4.64","6.53","8.53"],["2022-03-01","3.37","4.62","6.83","9.21"],["2022-06-01","3.66","5.14","7.26","10.11"],["2022-09-01","3.74","5.62","8.15","10.30"],["2022-12-01","3.92","5.93","8.61","10.98"],["2023-03-01","4.08","6.23","8.85","10.80"],["2023-06-01","4.32","6.60","9.39","11.04"],["2023-09-01","4.57","6.73","9.27","11.35"],["2023-12-01","4.78","7.01","9.56","11.86"]]},"axis":{"rotated":false,"x":{"show":true,"type":"timeseries","localtime":true,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"fit":true,"outer":true,"multiline":false,"multilineMax":0,"format":"%Y:$QQ","values":["2019-01-01","2020-01-01","2021-01-01","2022-01-01","2023-01-01"]},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-center"},"format":"%Y-%m-%d"},"y":{"show":true,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false},"padding":{"top":3,"bottom":0},"primary":"","secondary":"","label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"},"max":14,"min":0},"y2":{"show":false,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"padding":{"top":3},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"}}},"chartLabel":"Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency","color":{"pattern":["#61AEE1","#B84645","#B1812C","#046C9D","#9FA1A8","#DCB56E"]},"interaction":{"enabled":true},"point":{"show":false},"legend":{"show":true,"position":"bottom"},"tooltip":{"show":true,"grouped":true},"grid":{"x":{"show":false,"lines":[],"type":"indexed","stroke":""},"y":{"show":true,"lines":[],"type":"linear","stroke":""}},"regions":[],"zoom":false,"subchart":false,"download":true,"downloadText":"Download chart","downloadName":"chart","trend":{"show":false,"label":"Trend"}}

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax, using Philadelphia Fed auto loan tradeline data.

Notes: The chart shows transition rates into 30-day delinquency and rates are balance-weighted. Data are annualized as four-quarter moving sums to account for seasonal trends. Borrowers are grouped by generation using their birth year. Baby Boomers are those born between 1946 and 1964, Generation X are 1965 to 1979, Millennials are 1980 to 1994, and Generation Z are 1995 to 2011.

Next, we show how auto loan delinquency has evolved by zip code average income, as measured by average adjusted gross income from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Statistics of Income. While all income areas now have delinquency rates slightly above the pre-pandemic level, this rise is the most pronounced for borrowers in the lowest-income areas, shown on the light blue line.

Delinquencies Rise Most for Borrowers in Low-Income Areas

Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency

{"padding":{"auto":false,"right":18,"left":23},"data":{"groups":[],"labels":false,"type":"line","order":"desc","selection":{"enabled":false,"grouped":true,"multiple":true,"draggable":true},"x":"Date","rows":[["Date","1 (lowest income)","2","3","4 (highest income)"],["2018-03-01","11.66","8.53","6.45","4.18"],["2018-06-01","11.61","8.18","6.45","4.12"],["2018-09-01","11.22","8.15","6.28","4.18"],["2018-12-01","11.53","7.99","6.32","4.22"],["2019-03-01","11.65","7.90","6.25","4.31"],["2019-06-01","11.57","7.78","6.02","4.26"],["2019-09-01","11.81","7.80","6.02","4.15"],["2019-12-01","11.40","7.99","5.88","4.19"],["2020-03-01","11.32","7.93","5.92","4.01"],["2020-06-01","10.32","7.14","5.32","3.76"],["2020-09-01","9.45","6.60","5.00","3.48"],["2020-12-01","9.06","6.12","4.81","3.28"],["2021-03-01","8.47","5.71","4.62","3.25"],["2021-06-01","8.35","5.65","4.68","3.25"],["2021-09-01","8.33","5.44","4.57","3.22"],["2021-12-01","8.32","5.35","4.46","3.11"],["2022-03-01","8.79","5.42","4.63","3.11"],["2022-06-01","9.85","5.98","4.99","3.26"],["2022-09-01","10.73","6.65","5.44","3.45"],["2022-12-01","11.22","7.06","5.86","3.79"],["2023-03-01","11.52","7.46","5.90","4.06"],["2023-06-01","12.06","8.05","6.21","4.27"],["2023-09-01","12.37","8.19","6.17","4.43"],["2023-12-01","12.85","8.64","6.39","4.58"]]},"axis":{"rotated":false,"x":{"show":true,"type":"timeseries","localtime":true,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"fit":true,"outer":true,"multiline":false,"multilineMax":0,"format":"%Y:$QQ","values":["2018-03-01","2019-03-01","2020-03-01","2021-03-01","2022-03-01","2023-03-01"]},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-center"},"format":"%Y-%m-%d"},"y":{"show":true,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false},"padding":{"top":3,"bottom":0},"primary":"","secondary":"","label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"},"max":14,"min":0},"y2":{"show":false,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"padding":{"top":3},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"}}},"chartLabel":"Percent of balances transitioning into delinquency","color":{"pattern":["#61AEE1","#B84645","#B1812C","#046C9D","#9FA1A8","#DCB56E"]},"interaction":{"enabled":true},"point":{"show":false},"legend":{"show":true,"position":"bottom"},"tooltip":{"show":true,"grouped":true},"grid":{"x":{"show":false,"lines":[],"type":"indexed","stroke":""},"y":{"show":true,"lines":[],"type":"linear","stroke":""}},"regions":[],"zoom":false,"subchart":false,"download":true,"downloadText":"Download chart","downloadName":"chart","trend":{"show":false,"label":"Trend"}}

Sources: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax; IRS Statistics of Income.

Notes: The chart shows transition rates into 30-day delinquency and rates are balance-weighted. Data are annualized as four-quarter moving sums to account for seasonal trends. Borrowers are categorized into income quartiles by ranking zip code average income from lowest to highest and splitting zip codes into four equally sized groups by population.

The chart below shows average monthly payment amounts for new auto loans opened in that quarter, separated by zip code income. Interestingly, average monthly payments are very similar across income areas in nominal terms except for the highest-income quartile. All areas saw similar, sharp increases in payments on auto loans originated since 2019:Q4. However, the increase in monthly payments on loans newly opened in the lowest-income quartile would impose a much greater burden as a share of income than that faced by the highest-income group. The trend for origination amounts by area income (not shown) is similar to the trend for average payments. However, we note that the decline in the average origination balance in recent quarters, shown in the first chart, is not being passed through to the average scheduled payments. This diverging pattern between origination amount and the monthly payment over the last year can be explained by the increase in interest rates on auto loans.

Payments on Newly Opened Auto Loans Climb Sharply

Average monthly payment (in U.S. dollars)

{"padding":{"auto":false,"right":18,"left":32,"bottom":0},"data":{"groups":[],"labels":false,"type":"line","order":"desc","selection":{"enabled":false,"grouped":true,"multiple":true,"draggable":true},"x":"Date","rows":[["Date","1 (lowest income)","2","3","4 (highest income)"],["2017-03-01","407","397","401","445"],["2017-06-01","396","388","397","440"],["2017-09-01","405","392","399","448"],["2017-12-01","418","405","407","443"],["2018-03-01","401","417","409","443"],["2018-06-01","403","394","413","435"],["2018-09-01","419","403","407","452"],["2018-12-01","431","422","429","472"],["2019-03-01","434","421","423","477"],["2019-06-01","434","421","419","463"],["2019-09-01","434","419","422","464"],["2019-12-01","436","417","437","462"],["2020-03-01","438","420","432","470"],["2020-06-01","434","436","421","463"],["2020-09-01","425","414","435","458"],["2020-12-01","447","438","441","471"],["2021-03-01","445","437","459","500"],["2021-06-01","441","458","456","520"],["2021-09-01","488","468","481","519"],["2021-12-01","510","484","500","557"],["2022-03-01","519","498","503","574"],["2022-06-01","534","503","518","558"],["2022-09-01","527","520","526","599"],["2022-12-01","542","534","555","615"],["2023-03-01","542","527","533","620"],["2023-06-01","541","521","541","616"],["2023-09-01","560","536","555","603"],["2023-12-01","564","545","562","623"]]},"axis":{"rotated":false,"x":{"show":true,"type":"timeseries","localtime":true,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"fit":true,"outer":true,"multiline":false,"multilineMax":0,"format":"%Y:$QQ","values":["2018-01-01","2019-01-01","2020-01-01","2021-01-01","2022-01-01","2023-01-01"]},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-center"},"format":"%Y-%m-%d"},"y":{"show":true,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"tick":{"centered":false,"culling":false,"values":["650","600","550","500","450","400","350"]},"padding":{"top":3,"bottom":0},"primary":"","secondary":"","label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"},"max":650,"min":350},"y2":{"show":false,"inner":false,"type":"linear","inverted":false,"padding":{"top":3},"label":{"text":"","position":"outer-middle"}}},"chartLabel":"Average monthly payment (in U.S. dollars)","color":{"pattern":["#61AEE1","#B84645","#B1812C","#046C9D","#9FA1A8","#DCB56E"]},"interaction":{"enabled":true},"point":{"show":false},"legend":{"show":true,"position":"bottom"},"tooltip":{"show":true,"grouped":true},"grid":{"x":{"show":false,"lines":[],"type":"indexed","stroke":""},"y":{"show":true,"lines":[],"type":"linear","stroke":""}},"regions":[],"zoom":false,"subchart":false,"download":true,"downloadText":"Download chart","downloadName":"chart","trend":{"show":false,"label":"Trend"}}

Sources: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax; IRS Statistics of Income.

Note: Borrowers are categorized into income quartiles by ranking zip code average income from lowest to highest and splitting zip codes into four equally sized groups by population.

Conclusion

With the pandemic policy supports in the rear-view mirror, delinquency rates for most credit types have been rising after having reached very low levels during 2021. Concentrating on auto loans, delinquency transition rates have pushed past pre-pandemic levels, and the worsening appears to be broad-based. Loans opened during 2022 and 2023 are, so far, performing worse than loans opened in earlier years, perhaps because buyers during these years faced higher car prices and may have been pressed to borrow more, and at higher interest rates. The increasing transition rates merit monitoring in the months ahead, particularly with the amplified distress shown by borrowers in lower-income areas.

Andrew F. Haughwout is the director of Household and Public Policy Research in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an economic research advisor in Consumer Behavior Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daniel Mangrum is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a regional economic principal in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is the economic research advisor for Household and Public Policy Research in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Crystal Wang is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Daniel Mangrum, Joelle Scally, Wilbert van der Klaauw, and Crystal Wang, “Auto Loan Delinquency Revs Up as Car Prices Stress Budgets,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 6, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/02/auto-loan-delinque....

Credit Card Delinquencies Continue to Rise—Who Is Missing Payments?

Borrower Expectations for the Return of Student Loan Repayment

Where Is Inflation Persistence Coming From?

Interactive Charts: Household Debt and Credit

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Lessons from Monetary History: The Quality-Quantity Pendulum

In the previous section, we saw how economic theories changed from Classical to Keynesian to Monetarist over the course of the 20th century. These changes were driven by historical events. Taking this historical context into account deepens our understanding of economic theories. This contrasts with the conventional methodology of economic textbooks, which treats economic theories as scientific laws, which are universally applicable to all societies. In this section, we describe one of the central lessons which emerges from the study of money over the millennia.

The transition of economic theories from Classical to Keynesian to Neoclassical can be seen as a miniature illustration of the Quality-Quantity Pendulum, which is a consistent pattern relating to money observed over millennia. Modern economic theory strips theories of their historical context, depriving us of critical insights into both theories and history. Before studying the QQ Pendulum, we will pause to discuss how this defective methodology was adopted by economists.

The Battle of Methodologies: As Geoffry Hodgson has detailed in his book entitled “How Economists Forgot History”, a challenger to the dominant historical and qualitative methodology emerged in the late 19th Century. The new methodology was quantitative, mathematical, and empirical, in imitation of scientific methodology. The devastation of World War 1 destroyed the prestige of the traditional approach to social science, so that this scientific approach became the dominant methodology in economics by the 1950s. This ahistorical approach blinds us to the fact that all social theory is developed to analyze a particular society situated in a particular historical context. Treating it as a universal scientific law, invariant across time and space, is hugely mistaken.

Lessons from History: In this section, we will discuss some insights about the nature of money, and monetary economies, derived from the study of history by Glyn Davies in “A History of Money: From Ancient Times to Modernity”. Davies writes that: “… despite the antiquity and ubiquity of money its proper management and control have eluded the rulers of most modern states partly because they have ignored the wide-ranging lessons of the past or have taken too blinkered and narrow a view of money.” For example, Keynesians and Monetarists agree that a contraction of the money supply was the immediate cause of the Great Depression of 1929, ill effects of which persisted until the outbreak of World War 2 in 1942. From a broader perspective, a study of the history of money should have made both the nature of depression, and the remedy, abundantly clear. Unfortunately, as the previous quote indicates, policymakers ignored the lessons history teaches us about the role of money, and made errors which caused misery to millions for decades.

Money as a Social Institution: A study of history shows that money has played a central role in shaping history across the centuries. Also, history teaches us money is not purely a transaction technology; it is deeply embedded into the social fabric of society. Use of money requires building social consensus on trustworthiness of the monetary institutions. Building this trust requires building high quality institutions and mechanisms, which guarantee the value of money in the eyes of the public. The quality of money refers to the public trust and social consensus both on the value of money, and the stability of this value across time.

High Quality Money: History provides us with an incredibly diverse set of examples of monetary institutions which provided society with trustworthy money with stable value across time. Cattle and cowries in Africa, paper money in China, Wampum in America, and Yap stones in Pacific Islands, were used as money for centuries. Many systems even survived in competition with modern monetary systems. So, we conclude that there is a wide variety of ways to create high quality money.

The Gold Standard: One of ways to create high quality money is to use gold or silver. These metals have characteristics – discussed in textbooks – which make them particularly suitable for use as money. There is very little public awareness that there are many different varieties and conflicting interpretations of what “gold standard” means. The best reference for this is Morrison’s England’s Cross of Gold: Keynes, Churchill, and the Governance of Economic Beliefs. The strictest form of the standard – use of actual gold – has been very rare, historically. Coins of minted gold have been far more popular. The mint certifies the quantity and quality of gold in the coin, making it far more convenient for public use.

Minted Money and Token Money: The highest quality of money comes from minted coins which have value equal to the content of the metal (gold or silver). This is because the coin itself is the guarantor of its own value. There is still the question of what it is about gold and silver that creates nearly universal consensus on their intrinsic value? Perhaps the answer is that love of gold and silver has been built into human nature, as an ayah of the Quran suggests. The numismatic evidence from buried coins shows that high quality gold coins are almost always followed by “debased” coins – coins with significantly less gold content than the face value of the coin. History tells us of the varied reasons for such debasements. Most often, high expenses of wars require vast amounts of money, beyond available stocks of gold. Governments resort to debasement, to get more money from the same gold stock. Since gold is very valuable, even the smallest gold coins are not useful for daily transactions. So, token monies, made of copper or other cheap metals, are often used for small change. The metal value of these coins is not equivalent to their market value – instead, these coins considered as fractions of the gold coin, and are exchangeable.

From Quality to Quantity: The lesson of history, repeated across the globe, and across the centuries, is that the temptation to expand the stock of money – more quantity – proves irresistible in the long run. A modest expansion of money stock via small dilutions of gold content or small issues of token money, brings major economic benefits. Small expansions of money stock beyond gold content do not cause noticeable changes in the public trust which is the central guarantor of the value of money. However, over a longer period of time, the temptation to expand the quantity over safe limits becomes irresistible. Events like wars, or private greed, or government need, lead to over-expansion of the money stock. An excessive quantity of money causes inflation, a loss of value, and a breakdown of public confidence in money. The drive to expand the money stock leads to low quality of money. But large fluctuations in the value of money disrupt the lives, and cause distress to all members of a monetary economy. As a result, consensus builds on monetary reforms required to create high quality money. Eventually, excess money is removed from circulation, and a high quality money is restored, to complete the swing of the pendulum between quality and quantity.

The Pendulum of Economic Theories: Many authors have noted that history is a battle between the creditors and the debtors. In eras of high quality money, money is scarce, and the creditors are few and powerful. They propagate pro-creditor economic theories which favor “sound” money: high quality with restricted quantity. However, the need for expansion of money stock becomes overwhelming in many different scenarios. Then the pro-debtor economic theories emerge. These favor the expansion of the money stock, and cite numerous advantages from doing so. Creditors argue in vain against the slippery slope of modest expansions leading to ruin. The benefits from expansion are immediate and obvious to all. But in the long run, their gloomy predictions turn out to be valid. Over-expansion destroys the quality of money, and also the reputation of the pro-debtor economic theories.

This drama has played out over the centuries in many different guises, and with different terminologies in use to describe the two opposing schools of thought about money. Confusingly, the quantity theory of money (QTM) advocates maintenance of high quality money, and argues against expansions of the money stock to bring prosperity to the masses. The Real Bills doctrine versus the QTM, the Anti-Bullionists versus the Bullionists, the Banking School versus the Currency School, Keynesians versus Monetarists, and most recently, Minsky’s Financial Fragility Hypothesis versus the Real Business Cycle theories, are all illustrative of the quantity-quality controversy which spans centuries of monetary history.

Long-Run Versus Short Run Perspectives: Davies emphasizes that this quantity-quality pendulum becomes discernible only in the long run. Over any short period of time, spanning a few decades, the immediate benefits of one or the other school of thought seem overwhelming. When tight money is creating recession and unemployment, the benefits of looser money seem obvious to all, and tight money adherents find little support for their positions among the masses. However, in periods of high inflation, the harms of loose money again appear obvious, and tight money policies gain public support. Over any short period of time, one or the other policy seems obviously superior. It is only a long-term examination of history which shows the regularity with which the pendulum swings between the two poles.

There are three conclusions we would like to draw from the quantity-quality pendulum, which emerges from the study of millennia of monetary history.

- The study of equilibrium is an illusion. A stable and high-quality money creates an irresistible temptation towards expansion, leading to a breakdown in quality. Also, excessive money stock which destabilizes the value of money creates powerful forces which seek to stabilize its value and create high quality money. At no point in the trajectory of the monetary pendulum do we see any resting place, or equilibrium.

- The value of money rests on the social consensus created by confidence in the monetary institutions governing the creation of money. History is full of examples where this confidence was weakened or strengthened, leading to changes in the value of money. Recently, a crisis of confidence in the Euro was stemmed simply by an announcement by Mario Draghi the he would do “whatever it takes” to stabilize and protect the Euro. Conventional treatments of money pay no attention to these psychological aspects of money.

- The historical perspective provides deeper insights into monetary theory than conventional methodology. When the Great Depression created tight money, Keynesian theory favoring expansion of money stock emerged and became popular. Inflation in the 1970’s led to rejection of Keynesian theory and a return to the tight-money policies implemented by Volker. Conventional methodology searches for absolute scientific truths, without realizing that truth may be relative to a particular historical context.

Links to Related Materials

- Bit.ly/ME01: Monetary Economies: A Historical Perspective

- Bit.ly/MONE02: Writeup of THIS video-lecture

- Bit.ly/WEAmom: Method or Madness? (battle of methodologies)

- Bit.ly/MONBX: Books on Monetary Theory and History

- Bit.ly/Azmmai: Modern Money and Inflation

Basics of Monetary Economies

I am planning to write a textbook on monetary economies. I will draft it section by section and chapter by chapter, and put down the drafts here for feedback and comments. The first section is given below – it is an introduction to the topic, and provides some motivation for the study, as well as hints of the methodology to be adopted.

Introduction & Motivation

A Monetary Economy is one in which the use of money is essential to the functioning of the economy. That is, without money, people would starve, and massive amounts of economic misery would result. Since monetary economies have dominated the world for centuries, this seems to us like a natural state of affairs. However, a study of history reveals that monetary economies came into existence only a few centuries ago, and eventually came to dominate the globe. Most pre-modern societies were not monetary economies. For instance, a feudal economy was not a monetary economy. The landlord owned the land, and workers on the land would receive all necessary support – food, clothing, housing, etc – from him. In return, they would work the land and produce crops, and provide other services. No money was needed for the basic necessities of life. The landlord could sell excess crops for money, and buy fineries from foreigners, but this was not essential for existence. Even today, in many areas of the world, rural subsistence economies far from urban centers are often self-sufficient, and can function without money. These non-monetary economies are excluded from the scope of our study.

Our goal in this textbook will be to clarify how monetary economies function, and how they have evolved over time. This is important because conventional modern textbooks of economics do not correctly describe monetary economies. In these textbooks, money does not serve an essential function. This point is recognized and articulated in these textbooks using the terminology “neutrality of money”. For instance, a popular textbook by Mankiw states that:

Over the course of a decade, for instance, monetary changes have important effects on nominal variables (such as the price level) but only negligible effects on real variables (such as real GDP). When studying long-run changes in the economy, the neutrality of money offers a good description of how the world works.

Exactly contrary to this, Keynes stated clearly in his landmark book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Prices, that money plays an important role in both short and long run – it is not neutral. If money is neutral, then money plays no essential role in the economy, and so there is no essential difference between monetary and non-monetary economies. In this textbook, we will explain how money, far from being neutral, is a central driver of economic activity. Conventional textbook analysis, which takes money as neutral, leads to deep misunderstandings about modern real world economies.

The false assumption of neutrality of money led to the failure of economists to understand the causes of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007, and also to their failure to take corrective actions which could have prevented the Great Recession which followed. The battle of ideas, embodied in economic theories about money, is described in “Completing the Circle: From the Great Depression of 1929 to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007”. It is useful to briefly outline how economic theories changed over the course of the 20th Century:

- Classical Economists argued for the neutrality of money, along with other ideas, which lead to the conclusion that unemployment can only be a short-run phenomena. In the long run, unemployment will be eliminated by the workings of the free market.

- Following the Great Depression of 1929, large amounts of unemployment which persisted for long periods of time was observed. This was directly in conflict with theories of classical economics.

- Keynes then came up with a new theory, which had many revolutionary ideas, dramatically different from the assumptions of classical economics. One of the central ideas was that money is not neutral. In particular, in the labor market, the supply and demand for labor, and hence the rate of employment is strongly affected by the quantity of money available.

- Keynesian ideas came to dominate macroeconomics for about three decades following World War 2. In particular, the idea that free markets will not automatically eliminate unemployment, leads to the necessity of the government policies required to create full employment. Application of Keynesian policies led to full employment in USA and Europe for about three decades.

- The oil shock of the 1970’s led to the failure of Keynesian policies. Development of monetarism by the Chicago school of economists led to the re-instatement of pre-Keynesian ideas about the neutrality of money and the idea that free markets lead to elimination of unemployment. This came to be known as neoclassical economics, because it rejected Keynesian ideas, and went back to classical economics.

- A concerted campaign was carried out by monetarists to discredit Keynesian theories and rebuild Economics on neoclassical foundations. See Understanding Macro III: The Rule of Corporations. This was highly successful. The Monetarists went from a minority and eccentric school to the mainstream orthodoxy by the early 1990s. It became impossible to publish Keynesian and post-Keynesian views in mainstream top-ranked journals.

- Over the decade of the 1990s economic performance in the Western world became flat – fairly low growth, but no ups and downs of business cycles which had been characteristic of capitalist economies for a long time. This led to celebrations of “the Great Moderation” by the monetarists. Robert Lucas, Nobel Laureate and leading Chicago schools economist, announced triumphantly in his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association in 2003, that we economists have conquered the business cycle, and from now on, recessions will not happen.

- The Global Financial Crisis of 2007 took the economics profession by surprise, just as the Great Depression of 1929 had come as a surprise. Paul Krugman wrote the book “The Return to Depression Economics” arguing that insights of Keynes continued to be valid, and to provide deeper insights into the GFC than was available from leading neoclassical macroeconomic theories of the time. Paul Romer wrote a scathing article entitled “The Trouble with Macro” in which he argued that modern macroeconomics is based on fundamentally flawed doctrines, and leads to wildly incorrect predictions.

This is more or less the current state of affairs, as good alternatives to conventional macroeconomics are unavailable in the mainstream. The mainstream macroeconomic theories are based on assumptions which have no relation to reality. For more details, see “Why Do Economists Persist in Using False Theories?”

We will conclude this introduction to monetary economies by discussing some of the key elements of the approach we will be using. First, while mainstream macroeconomics rejected Keynesian ideas, a group of theorists known as Post-Keynesians have continued to develop the ideas of Keynes, building on his fundamental insights. This has led a branch of macroeconomics which provides much deeper insights into modern economies then the monetarism which dominates universities today. Our text borrows from these ideas. However, the critical innovation of this textbook is to study economic theory within its historical context.

As described earlier, historical events, and economic crises, have played a major role in shaping economic theories. In fact, we cannot understand economic theory as an abstraction, removed from its context. This is in conflict with the claim implicit in the use of the word “science” – lessons from study of European societies are universally applicable to all societies across time and space (see: The Puzzle of Western Social Science). In fact, all social theory is developed as an attempt to understand historical experiences of a particular society, and cannot be understood as an abstraction, detached from this historical context. Studying economics within its historical context requires a methodology radically different from that currently in use, in both orthodox and heterodox textbooks of economics currently in use around the world. We will discuss this methodology in the next section.

Australia – inflation falling rapidly

Today (January 31, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Consumer Price Index, Australia – for the December-quarter 2023. The data showed that the inflation rate continues to fall sharply – down to 4.1 per cent from 5.2 per cent in line with global supply trends. There is nothing in this quarterly…

Waller Comments

Nick Timiroas highlighted an exchange from Fed Governor Waller (link to speech/interview transcript) on Twitter. This article consists of two rants based on the transcript, plus a bonus rant in the appendix based on what somebody else said.

Nick Timiroas highlighted an exchange from Fed Governor Waller (link to speech/interview transcript) on Twitter. This article consists of two rants based on the transcript, plus a bonus rant in the appendix based on what somebody else said.

David Wessel Hmm. Another question was what your view is about, what role did fiscal policy played in causing the inflation that you've been working so hard to restrain? How big an issue was fiscal policy and how big an issue is fiscal policy now, as you try and calibrate the right pace of monetary easing?

Christopher Waller Well, just from a, it's just a simple macroeconomics point of view. If you're going to increase the spending in the debt [sic?] by $6 trillion in a matter of two years, and then say that has no effect on demand, that seems just impossible to me. It isn't the only thing that contributed to the inflation, but it certainly has had to have had an impact. The reason I say that is, you know, people have been talking a lot about, oh, all the last six months shows this was all supply, all supply, all supply. Well, if these are temporary supply shocks, when they unwind, the price level should go back down to where it was. It's not.

Go to Fred. Pull up CPI. Take the log. Look at that thing. The level of inflation [sic?] is permanently higher. That doesn't happen with supply shocks. That comes from demand. And this was a permanent increase in demand and permanent increase in debt. So I think there clearly was in fact a fairly...

I am just going to go after the part of the text that I highlighted. Firstly, the “level of inflation being permanently higher” is either a mis-statement or not carefully thought through. So I will not sweat his exact wording and try to guess what he meant. (Why is his wording a problem? The inflation rate went up, and has since gone down. Although it might still be higher than previous averages, that would imply that one could claim that “inflation is permanently higher” every single time inflation rose in the 1950-2024 period. If he meant that “the price level is permanently higher,” well, that is how a 2% inflation target is actually supposed to work.)

My concern is the Economics 101ism of the analysis, which is all over the discussion of this topic. In the world of Economics 101, everything in the economy is the result of two lines intersecting. All discussions revolve around what happens when one — and only one — of those lines are allowed to move. (This can often devolve into a debate whether one of the lines is horizontal or vertical, which is Peak Economics 101.) In this case, there has to be either a supply shock, or a demand shock. It is forbidden that “demand” and “supply” change at the same time.

Although I am mere blogger with almost no academic training in economics even I was able to notice that the pandemic lockdown period saw the simultaneous impositions on the ability to produce goods (“supply shock”) as well as fiscal transfers designed to avoid Consumer Cash Flow Armageddon (“demand shock”). This was then followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine (supply shock), etc. Deaths, early retirements, and the shutdown of worker migration also created a supply shock in the labour market. Although I saw a lot of commentary putting weight on supply side factors for the inflation, I cannot recall any serious commentator saying that nothing happened on the demand side.

Meanwhile, the idea that the price level/inflation must go back to its previous level after the shock passes is remarkably static thinking. The supply shock also hit the labour market, and wages broadly rose. Empirically, higher nominal wage incomes implies higher nominal household expenditure — sustaining the higher price level. This is not like The Great Canadian Cauliflower Panic Of 2016 where there is a shock to a single commodity that has extremely limited effect on other prices; the whole structure saw price increases. The higher wages allows the economy to function with higher prices across the board, which is why we have aggregate wage and price levels in economic models in the first place.

Inflation is only supposed to head back down after the various markets sorted themselves out. Given the empirically demonstrated persistence of inflation, a model that predicts that inflation exhibits immediate steps up and down in response to “shocks” can easily be rejected.

Comments like this are why I think that the whole “supply versus demand” debate needs to be put out of its misery.

Side Rants

This episode also provides an interesting view into inflation psychology. The entire neoclassical enterprise is premised on everybody internalising the central bank target, and doing sophisticated calculations related to it. But back in the real world, I keep having conversations with/reading texts by people who are mad that prices are not going back to where they were in 2019. Given that Canadian inflation had been rising at an average close to the target 2% per year (and more if you believe the inflation truthers!) between 1990-2020, if people were really aware of what was happening to inflation, why would they ever expect prices to return to their previous level?

As a final aside, the somewhat garbled comment on debt could be turned into a little MMT rant. Deficits are outcomes of economic developments, and the exact monetary amounts are somewhat arbitrary in the sense that what constitutes a “stimulative” deficit depends on a lot of factors. (Some might object to the use of dollar amounts instead of a more sensible scaling versus GDP. I think the use of dollar amounts should be avoided in written communications about aggregate fiscal policy, but using them in verbal remarks is going to be more natural for someone who stares at economic data all day.)

Reserves Comments

Another comment by Waller caught my eye.

Christopher Waller Yeah. I mean, I made an argument for probably ten years. There's no economic theory that tells you how big a Central Bank's balance sheet should be. I know of no theory that tells you. You have Switzerland where, it's basically 100% of GDP or some number like that. So there's no real theory. And from a point of view of the reserves, I love a floor system because, as Milton Friedman once said, you want to put enough liquidity in the system that you satiate the system. So there's no scarcity or shortage.

I am in the process of going after another dubious theory of Milton Friedman (should be published next week), so I have no choice but to comment.

To the contrary of Waller’s assertion, there is an economic theory about the size of the central bank balance sheet, or at least part of it. The central bank’s balance sheet is equal to notes and coin holdings plus reserves held at the central bank. Notes and coins is literally a money demand function found in any mainstream monetary textbook (although one might debate how accurate the models are).

As for reserves, they are arbitrary. A banking system can function perfectly well with exactly zero reserves held overnight at the central bank. Reserve holdings are either a tax on banks (required reserves) or are pushed in by central bankers to replace short-dated Treasury securities (which they are economically equivalent to from the perspective of the private sector). (Admittedly, there are markets where banks hold reserves based on convention. Since conventions are arbitrary, the reserves required to meet them are arbitrary.)

If I have $100 in my bank account and my idiot bank insists that I hold that $100 “in reserve,” I cannot use that $100 to pay any incoming expenses. I have a stranded, illiquid asset that pays whatever interest rate my bank decides to offer on it. In the case of bank reserves, replace “idiot bank” with “idiot central bank” and you immediately see the issue with reserves that Economics 101 textbooks ignore.

If banks truly want to hold reserves at the central bank and not lend in wholesale money markets (including the interbank market), this is not a “money demand” issue. It is a signal that the central bank once again failed its core responsibility to properly regulate the banking system. Letting the banks bypass wholesale lending markets by using the central bank as an intermediary is just putting band-aid on a major wound. How many band-aids you apply is a secondary concern relative to dealing with the real problems.

Appendix: My Turn to Strawman!

Having just objected to a strawman argument about supply shocks, I will then turn around and hit my own strawman. To be clear, this is not based on the Waller interview. Rather than create a new article, I will just throw this little rant (based on some recent comments I saw elsewhere) into this appendix.

I have seen comments to the effect that the rise in nominal GDP tells us that we would have an inflation problem.

Any time someone uses nominal GDP in such a context, please return to the following (approximate) identity. (You could use logarithms to be exact.)

Nominal GDP growth rate = (deflator inflation rate) + (real GDP growth rate).

Look at that equation. Ask yourself this: under what circumstances will the deflator inflation rate go off in a completely direction than nominal GDP growth (ignoring very short period rates of change, where it does)? How often do we see this medium-term divergence in practice?

After that exercise, one can then question why someone would suggest using nominal GDP trajectory as a cause of inflation?

Email subscription: Go to https://bondeconomics.substack.com/

(c) Brian Romanchuk 2024

Beyond the average: patterns in UK price data at the micro level

Lennart Brandt, Natalie Burr and Krisztian Gado

The Bank of England has a 2% annual inflation rate target in the ONS’ consumer prices index. But looking at its 700 item categories, we find that very few prices ever change by 2%. In fact, on a month-on-month basis, only about one fifth of prices change at all. Instead, we observe what economists call ‘sticky prices’: the price of an item will remain fixed for an extended amount of time and then adjust in one large step. We document the time-varying nature of stickiness by looking at the share of price changes and their distribution in the UK microdata. We find a visible discontinuity in price-setting in the first quarter of 2022, which has only partially unwound.

Theory of sticky prices and related literature

Understanding price-setting dynamics is essential for central banks. Most structural models in the literature use a form of time-dependent pricing, under which firms keep prices the same for fixed amounts of time (Taylor (1980)), or for random amounts of time such that there is uncertainty about the precise length of the price spell (Calvo (1983)). Another way of modelling sticky prices emphasises that firms will not just look at the time that has passed since they last adjusted its price, but also at how far their price is from some desired price level. This is called state-dependent pricing. Macroeconomic models don’t typically allow for time-variation in the degree of stickiness or switching between pricing strategies. Recently, however, firms in the Decision Maker Panel tell us that they have moved increasingly away from time-dependent towards state-dependent pricing. In this case, when there is a large shock affecting many firms, the shock leads to an increased frequency of price changes and so more immediate pass-through to overall inflation.

In order to better understand the pricing behaviour of firms in times of large inflationary shocks, we explore the pricing dynamics at the micro level using CPI microdata published by the ONS. We are of course not the only ones who have been interested in this type of data. Bank authors have been using this data set for a number of years. For example, Bunn and Ellis (2011) document stylised facts about pricing behaviour from the UK microdata and the August 2020 Monetary Policy Report used CPI microdata to inform policy. Elsewhere, Karadi et al (2020) use US microdata to analyse firms’ price-setting in response to changes in credit conditions and monetary policy. Nakamura et al (2018) analyse the societal cost of high inflation using microdata from the 1970s and 1980s, and Montag and Villar (2023) analyse the effect of more frequent price-changes on aggregate inflation during Covid. Relatedly, Davies (2021) finds that the difference between the share of price rises and price cuts in the UK microdata is related to aggregate inflation, focusing on price-setting during the pandemic. And finally, authors of the FT’s Alphaville blog have also been looking into these data (see here and here).

The data

The microdata spanning from 1996 until September 2023 is publicly available and updated monthly after each CPI release. It contains the monthly price quote data underpinning the ONS’ CPI series for over 700 items with identifiers at the shop, shop type, and region levels. We clean the data which works out to about 30 million observations. When identifying a price change in the data, which is ultimately what matters for inflation, we try to be as precise as possible with regards to the product and the timing of the change. To that end we only count the change if we find the same item, in the same region, in the same shop, in two exactly neighbouring months. For example, if a bag of potatoes cost £2 in January and £3 in March but was not recorded in February, rather than imputing a price we discard the observation since we cannot be sure in which month the change actually happened.

Stylised facts from the microdata

A brief look at the data lets us establish some stylised facts. Chart 1 shows a decomposition of these month-on-month price movements over all items in the data set. Four key observations stand out:

- Prices rise and fall all the time, but the vast majority of prices do not change between months. In any given month, on average since 1996, around 80% of prices remain unchanged relative to the previous month (blue line).

- The share of prices rising (in green) has increased notably since 2021 to an extent that has not happened in previous inflationary episodes in the sample (excluding VAT changes).

- The share of prices falling (in red) has fallen somewhat but remains stable since 2021, relative to historical average. The main margin of adjustment has been in the share of price increases.

- But, in recent months, while the share of prices rising has tapered off, it remains elevated relative to its historical average.

Chart 1: Decomposition of price movements month-on-month

Notes: The share of prices rising and falling reflect month-on-month changes. Shares are seasonally adjusted using the R package seasonal. Spikes in 2008, 2010 and 2011 are a consequence of UK VAT changes (17.5% to 15% in 2008, increase to 17.5% in 2010 and increase to 20% in 2011). The grey shaded area covers the time between March 2020 and July 2021 when the economy (and data collection) was most affected by the Covid pandemic. Dashed lines show the 2011–19 averages. Latest observation: September 2023.

Sources: ONS and authors’ calculations.

To be clear, this chart is not saying that 80% of products never change prices. If the price of an item remained constant between December and January, and rose between January and February, it would move from the blue into the green category during this period. Similarly, it would fall out of the green, into the blue or red, if from February to March the price again remained constant, or fell, respectively.

So, perhaps surprisingly, this chart shows that monthly price dynamics in the economy are driven by only a relatively small fraction of roughly 20% of all goods and services in the consumption basket. Also, we see that in the most recent episode, the shift into rising prices has been mostly out of the ‘no change’ category. Hence, fewer prices are staying fixed, and more are rising. It is worth noting that the recent up-tick in the shares of prices rising is only matched historically by those caused by VAT changes in 2008, 2010 and 2011, which however appear as one-off price spikes rather than a persistently higher share of price rises, as in 2022.

If it is a minority of total products whose price changes, it is important to take a closer look. Chart 2 shows the distribution of prices changes from 2019 by quarter (truncated at zero to exclude no-change observations). In line with the rise in the green line in Chart 1, we observe that over 2021 and 2022 a lot of mass moved into the right side of the distribution, that is the share of price increases, with the share of price decreases being relatively stable.

Chart 2: Evolution of the distribution of price changes by quarter 2019–23

Notes: The share of prices that did not change is excluded from these densities. The truncated densities are estimated in R via the Bounded Density Estimation package using the boundary kernel estimator. Darker colours correspond to quarters in which year-on-year CPI inflation was relatively high, lighter colours to quarters in which it was low. Each distribution represents month-on-month changes within the same quarter. Latest observation: 2023 Q3.

Sources: ONS and authors’ calculations.

A note on the chart: the distribution of price changes, when aggregate inflation is at or close to target, is roughly symmetric in logarithms. On this scale, a doubling (+100%) is equally far away from zero as a halving of the price (-50%). Due to sales, the doubling and halving of prices actually happens regularly in the data, which explains the bunching around these points. While these may be a source of seasonality in the data, which may obscure the underlying dynamics, we do not believe they are important for the overall shape of the distribution which we show here.

In Chart 3, we zoom in on a couple of these densities to better see differences in their shape. They are the densities corresponding to price changes in the third quarter of 2022 and 2023 alongside an average density over the pre-Covid period.

Chart 3: Comparison of densities from 2022 and 2023 against a pre-Covid average

Notes: The share of prices that did not change is excluded from these densities. The truncated densities are estimated in R via the Bounded Density Estimation package using the boundary kernel estimator. To compare densities across time, they are normalised to sum to the average share of prices falling and rising respectively within the quarter. The yellow line shows the pointwise average density over the third quarters of the years 2011–19.

Sources: ONS and authors’ calculations.

We can see how, compared to this historical average – which we use as a stand-in for pricing behaviour when inflation was close to the 2% inflation target – 2022 saw a huge number of prices increase while there was little change in the behaviour of the lower part of the distribution. In the latest data, this mass of increases has begun to subside, and, at the same time, there is a growing number of prices outright falling on the month. However, the modal price increase (that is, the most probable) is still elevated at about 6%, compared to roughly 3% on average during 2011–19).

Conclusion

To summarise, looking at the micro level of price changes, we find a visible discontinuity in price-setting in the first quarter of 2022. A variety of factors, such as the large rise in energy prices in early 2022, as well as supply-chain issues following Covid lockdowns, likely contributed to this significant change in price-setting dynamics in the UK (relative to any recent historical precedent at least). At the micro level, firms’ pricing decisions led to the emergence of a large rebalancing in the distribution of price changes. Suddenly, more prices for many different products were rising at the same time. Compared to the available history for these data, the recent period is unique. More research will be needed on the causes of this marked shift in the distribution of price changes, both at a micro and at a macro level.

In the very latest data, there is some evidence that the distribution of price changes has indeed begun to return in the direction of its historical average, though it is too soon to establish a trend.

Lennart Brandt and Natalie Burr work in the Bank’s External MPC Unit, and Krisztian Gado is a PhD candidate at Brandeis University.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Japan inflation now falling fast – monetary and fiscal policy settings have been vindicated

The latest information from Japan suggests that in December 2023, its inflation fell sharply for the second consecutive month and that one might conclude the inflation episode is coming to an end. The Bank of Japan made the assumption that this supply-side inflation was temporary and would subside fairly quickly once those constraints eased. And…

The great economy Trump left Biden

from Dean Baker We have been seeing numerous stories in the media about how people support Donald Trump because he did such a great job with the economy. Obviously, people can believe whatever they want about the world, but it is worth reminding people what the world actually looked like when Trump left office (kicking […]

Australian inflation rate falls sharply as supply pressures ease

Today’s post is a complement to my post on earlier this week – So-called ‘Team Transitory’ declared victors (January 8, 2024). Yesterday (January 10, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics published the latest – Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator – for November 2023, which showed another sharp drop in inflation. The data are the closest…

Whether real wages have stopped declining depends on how one measures it

For the time being I will continue my Wednesday format where I cover some things that crossed my mind in the last week but which I don’t provide detailed analysis. The items can be totally orthogonal. The latest inflation data for Australia continues to affirm the transitory narrative – dropping significantly over the last month.…