philosophy

Notably Good Experiences with Philosophy Journals

As stories of philosophy journal horror stories continue to come in, one commenter made a suggestion.

[This post was originally published on March 3, 2021. It has been reposted by request of a reader.]

[Jim Picôt, “Love Heart of Nature” (photo of shark swimming in a heart-shaped school of salmon)]

If part of the reason for sharing such stories was to possibly reveal some common problems or patterns with an important part of the world of academic philosophy, then, says Kaila Draper, “Maybe we should have a thread about really good experiences with referees and journals so that more patterns can be detected.”

Good idea!

Readers, if you’ve had a delightful, beneficial, super-efficient, caring, understanding, or even just notably good experience with a philosophy journal, please share it.

And just to get it out of the way, while we are very happy for you, “They accepted my article!” doesn’t qualify.

The post Notably Good Experiences with Philosophy Journals first appeared on Daily Nous.

Swallows, Moles, and other Animal-Philosopher Typologies

“There are two kinds of philosophers: swallows and moles.”

The swallow and the mole are offered up by Edouard Machery (Pittsburgh) in a recent review of The Weirdness of the World by Eric Schwitzgebel (UC Riverside).

He writes:

Swallows love to soar and to entertain philosophical hypotheses at best loosely connected with empirical knowledge. Moles, on the contrary, rummage through mundane facts about our world and aim at better understanding it.

Which philosophers are swallows and which are moles?

Note that the swallow-mole distinction is not to be confused with the fox-hedgehog distinction (from Archilochus, usually via Isaiah Berlin). The fox knows many things, while the hedgehog knows one big thing.

A further question, of course, is what other animal pairs would make for helpful, or, if not helpful, at least amusing, typologies of philosophers?

Here are some possibilities:

- Ants and Anteaters.

Ants do their specific little jobs as part of creating and maintaining the collective body of knowledge. Anteaters paw through the anthill, slurping up what they need, leaving destruction and confusion in their wake. - Dogs and Cats.

Dogs are happy to approach you or play with any idea you throw at them, just for fun. Cats may interact with you but usually only if you’re doing something for them. - Snakes and Glass Lizards.

Snakes are always doing something potentially important: if a snake is nearby, you better pay attention. Glass Lizards are a type of legless lizard that is not a snake (despite that you might have thought that the definition of a snake was “legless lizard”) and are constantly making distinctions that do not make a difference.

Discussion and suggestions welcome (but please play nice).

The post Swallows, Moles, and other Animal-Philosopher Typologies first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Quickest Revolution: An Insider’s Guide to Sweeping Technological Change, and Its Largest Threats – review

In The Quickest Revolution, Jacopo Pantaleoni examines modern technological progress and the history of computing. Bringing to bear his background as a visualisation software designer and a philosophical lens, Pantaleoni illuminates the threats that technological advancements like AI, the Metaverse, and Deepfakes pose to society, writes Hermano Luz Rodrigues.

The Quickest Revolution: An Insider’s Guide to Sweeping Technological Change, and Its Largest Threats. Jacopo Pantaleoni. Mimesis International. 2023.

“This changes everything” is perhaps the most hackneyed phrase found in YouTube videos when the topic happens to be new technologies. Such videos typically feature enthusiastic presenters describing the marvellous potentials of a soon-to-come technology, and a comment section that shares the same optimism. These videos proliferate daily, receiving hundreds of thousands of views. Regardless of whether we take them at face value or with extreme scepticism, their abundance illustrates the craze for technological progress, and more importantly, that a critical view of this attention is wanting.

“This changes everything” is perhaps the most hackneyed phrase found in YouTube videos when the topic happens to be new technologies. Such videos typically feature enthusiastic presenters describing the marvellous potentials of a soon-to-come technology, and a comment section that shares the same optimism. These videos proliferate daily, receiving hundreds of thousands of views. Regardless of whether we take them at face value or with extreme scepticism, their abundance illustrates the craze for technological progress, and more importantly, that a critical view of this attention is wanting.

Pantaleoni uses theories such as Moore’s Law, which explains an exponential growth phenomenon, and inputs from his career and personal experiences, to frame the history of, and the philosophical ideas driving, technological change.

In The Quickest Revolution, Jacopo Pantaleoni aims to fill this gap by supplying the reader with a critical, yet personal, analysis of modern technological progress and its impact on society. Coming from a background in computer science and visualisation software development, Pantaleoni uses theories such as Moore’s Law, which explains an exponential growth phenomenon, and inputs from his career and personal experiences, to frame the history of, and the philosophical ideas driving, technological change.

The first few chapters of the book are devoted to a survey of the defining moments of pre-modern scientific advancements in the Western world. The chapters include breakthroughs from historical figures such as Copernicus, Galileo and Bacon. The author then fast-forwards to the 20th century to briefly introduce the achievements of the godfathers of computer science like Alan Turing. The descriptions of these events foreshadow the book’s main focus on contemporary technological development and its concerns. In the latter, Pantaleoni approaches many tech-related keywords trending today from a philosophical perspective: AI, Metaverse, Deepfakes, and Simulation, among others.

what distinguishes Pantaleoni’s approach is the fact that he analyses these themes with a gaze that stems from the fields of realistic visualisation and simulation.

While such at-issue discourses on contemporary technology may be plentiful among enthusiasts (eg, podcasts like Lex Fridman), what distinguishes Pantaleoni’s approach is the fact that he analyses these themes with a gaze that stems from the fields of realistic visualisation and simulation. This distinction is not to be taken lightly. Throughout the book, there are surprising overlaps between these specific fields and society’s perception and interest in technology. For example, the author notes how films such as The Matrix, which used technology to simulate and depict “another reality that did look real”, offer proof of “how deeply computer graphics has been affecting our culture” (185). In fact, he argues that not only did sci-fi and CGI-laden media foment interest in stories about simulated worlds, but the technological achievements of such productions heavily contributed to society’s adoration and pursuit of advancements in realistic visualisations and simulations.

Pantaleoni acknowledges that society’s pursuit of a realistic-simulated future is replete with potential benefits, such as reduction of operation costs, accessibility through remote work, and engagement by telepresence. But, he notes that it may bring forth undesirable consequences

Pantaleoni acknowledges that society’s pursuit of a realistic-simulated future is replete with potential benefits, such as reduction of operation costs, accessibility through remote work, and engagement by telepresence. But, he notes that it may bring forth undesirable consequences to the physical world. For him, such aspirations implicitly denote a belief that “advances in photorealistic rendering, networking, and artificial intelligence will provide us the tools to build a better version of reality” (244). He cautions that this reality exodus neglects existing problems, and poses the question: “If we are failing to set things straight in the real world, what chances do we have to fair better, or ‘do it right’ in a hypothetical Metaverse?”(244).

The book makes the case that there are signs that the hitherto inexorable drive for progress in these technologies is leading to devastating effects. As practical examples, the author cites the impacts these technologies have had on political elections, the economy, and collective identity, among others. The book also underscores how physical and virtual/simulated have become increasingly intertwined through technology. Sherry Turkle observed this phenomenon many years prior in her presentation Artificial Intelligence at 50: “When Animal Kingdom opened in Orlando, populated by ‘real’, that is, biological animals, its first visitors complained that these animals were not as ‘realistic’ as the animatronics creatures in Disneyworld”. That is, while the animatronics featured “typical” characteristics, the real animals were perceived as static in comparison.

In a similar fashion, Pantaleoni recognises the capacity of contemporary technologies to shift perceptions and recoil in society as proxies. He writes that the overwhelming majority of Deepfakes, for example, either create pornographic or troubling scenes using celebrities. Furthermore, he notes that Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots are capable of impersonating a human being and that AI is automating both physical and mental human labour.

Whatever risks these new technologies seem to embody, however, are often brushed off by enthusiasts. This rather careless stance might be due to what Pantaleoni describes as a “blind” faith in technological progress, a belief akin to a “new and widely spread religion” (242). At its core, this techie religion is based on the imperative that technological growth is not to be questioned or impeded, for it makes “promises of a better reality” (243).

While previous technologies were essentially engineered by humans, society is transitioning towards new technologies that are increasingly autonomous and uncontrollable

Two arguments regarding the implications of this “religion” may be extracted from the book. The first argument is that for the zealots, it doesn’t matter how things progress (the means), as long as they continue to do so (produce results). While previous technologies were essentially engineered by humans, society is transitioning towards new technologies that are increasingly autonomous and uncontrollable, because these new technologies produce results that are “far much better than any handcrafted algorithm a human could make”(126).

Similar to the deceiving Mechanical Turk of the 18th century, many of today’s black-box technologies are very convincing in providing an illusion of their capabilities, while little is known about their under-the-hood properties or actual affordances.

The second argument is that what is perceived as progress may actually be a sort of artifice. Similar to the deceiving Mechanical Turk of the 18th century, many of today’s black-box technologies are very convincing in providing an illusion of their capabilities, while little is known about their under-the-hood properties or actual affordances. This concealment of properties and their seductive realism lure techno enthusiasts because of their desire to believe in them. Pantaleoni reminds us, however, that image-generative AI models, for instance, “know nothing about physics laws and accurate simulations” (141). Instead, it achieves extreme realism by feeding millions of training examples (141).

Throughout the book, Pantaleoni engages the reader in the challenges of technological development, through a distinct and compelling gaze – that of his specialisation in realistic visualisation software. Moreover, he does so in the tone of a passionate advocate of technology and a worried critic. There are a variety of contemporary “revolution” topics and discussions, such as the ethics behind the implementation of new technologies or its impact on the economy, and depending on each reader’s preferences and interests, some will resonate more than others. However, readers are likely to find the historical accounts narrated in the first few chapters disjointed from the book’s focus. These accounts are broad and familiar, with much of its content being assumed knowledge for most readers. Nevertheless, Pantaleoni offers notable contributions to the field with his shrewd observations anchored by his vast experience. In a field saturated with either theorists or quacks, it is especially commendable to read a book from the perspective of a practitioner.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Bruce Rolff on Shutterstock.

Q and A with Jonathan White on In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea

We speak to Jonathan White about his new book, In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea, which investigates how changing political conceptions of the future have impacted societies from the birth of democracy to the present.

On Tuesday 30 January 2024 LSE staff, students, alumni and prospective students can attend a research showcase where Jonathan White will discuss the book.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea. Jonathan White. Profile Books. 2024.

Q: What is the value of examining democracy in terms of its orientation towards, or relationship to, the future?

Q: What is the value of examining democracy in terms of its orientation towards, or relationship to, the future?

My book tries to show how beliefs about the future shape expectations of who should hold power, how it should be exercised, and to what ends. The emergence of modern democracy in Europe coincided with new ways of thinking about time. In the 18th and 19th centuries, emerging ideas of a future that could be different from the present and susceptible to influence helped to spur mass political participation. Movements of the left cast the future as the place of ideals, and “isms” such as socialism and liberalism provided the basis on which strangers could find common cause. Conversely, authoritarians have used the future differently to pacify the public and keep power out of its hands. Projecting democracy, prosperity and justice into the future is one way to seek acceptance of their absence in the present.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, emerging ideas of a future that could be different from the present and susceptible to influence helped to spur mass political participation.

Q: Why is an emphasis on continuation beyond the present essential to the operation of democracy?

Modern democracy is representative democracy, and that gives the future particular significance. Why should people accept the results of elections that go against them? “Losers’ consent” is generally said to rest on the notion that victories and defeats are temporary – there will always be another chance to contest power. The expected future acts as a resource for the acceptance of adversaries and of mediating institutions and procedures. One of today’s challenges is that this sense of continuation into the future is increasingly questioned. Problems of climate change, inequality, geopolitics and social change are widely viewed as so urgent and serious that they remove any scope for error – waiting for the “next time” is not enough. Every political battle starts to feel like the final battle, to be won at all costs. This year’s US presidential election will be fought in these terms and will make clear the stresses it puts on democracy.

One of today’s challenges is that this sense of continuation into the future is increasingly questioned. Problems of climate change, inequality, geopolitics and social change are widely viewed as so urgent and serious that they remove any scope for error

Q: You credit liberal economic thinkers like Adam Smith with “pushing back the temporal horizon”. How did their ideas around the free market treat the future?

In the early Enlightenment, defenders of free trade and commerce tended to emphasise the dividends that could be expected in the short term – peace and stability, for example, and access to goods. But the legitimacy of the market order would be hard to secure if it rested only on immediate benefits. What if conditions were harsh, or wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few? Pioneers of liberal economic thought such as Smith started to promote a longer perspective, allowing them to cite benefits that would need time to materialise, such as advances in efficiency, productivity and innovation. The future could also be invoked to indicate where present-day injustices would be ironed out. What we now know as “trickle-down” economics, in which returns for the rich are embraced on the idea that they will percolate down to the many, entails pointing to the future to defend the inequalities of the present. By invoking an extended timeframe, one can seek to rationalise a system that otherwise looks dysfunctional.

Pioneers of liberal economic thought such as Smith started to promote a longer perspective, allowing them to cite benefits that would need time to materialise, such as advances in efficiency, productivity and innovation.

Q: You cite the 20th-century ascendance of technocracy, of “ideas of the future as an object of calculation, best placed in the hands of experts”. How has this impacted democratic agency?

One way to think about the future is in terms of probabilities – what outcomes are most likely and how they can be prepared for. You find this outlook in business, and in government – especially in its more technocratic forms. It brings certain things with it. A focus on prediction and problem-solving often means focusing on a relatively near horizon – a few years, months, weeks or less – as where the future can be gauged with greatest certainty. And that in turn tends to go with a consciously pragmatic form of politics, less interested in the longer timescales needed for far-reaching change. In terms of the democratic implications, a focus on probabilities tends to elevate the role of experts – economists, for example – as those able to harness particular methods of projection such as statistics. If you turn the future into an object of calculation, it tends to favour elite modes of rule.

An emphasis on prediction is also something that has shaped how politics is covered in the media. Consider the use of opinion polls to narrate change – increasingly prominent from the 1930s onwards – which encourage a spectator’s perspective. Or consider a style of reporting quite common today, whereby a journalist talks about “what I’m hearing in Washington / Westminster / Brussels”. Its focus is on garnering clues about who seems likely to do what, and what they think others will do. The accent is less on the analysis of how things could be, or should be, or indeed currently are, and more on where they seem to be heading. It is news as managers or investors might want it – and politically that often amounts to an uncritical perspective.

Q: You discuss how desires to calculate the future through military forecasting took hold during the Cold War. What are the legacies of this in governmental politics today?

One of the main functions of military forecasting during the Cold War was to second-guess the actions of enemy states – where their weaknesses lay, where they might attack, and so on. That was true in both the West and the East. But forecasting was also applied to the control of populations at home, and not just with an eye to foreign policy. Fairly early on, national security experts started to get involved in public policy and urban planning – think of initiatives such as the “war on crime” launched by US President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. The outlook of the military forecaster began to transfer from the realm of geopolitics to public policy, counterinsurgency and the management of domestic protest, bringing methods of secrecy with it. Today’s forms of surveillance governance are the descendants of these forecasting techniques. And so too are conspiracy theories, which are often based on the idea that some have more knowledge of the future than they let on. Theories of 9/11 that suggest the US government saw the attack coming and deliberately let it happen, or even assisted it, are emblematic.

Q: Why is reducing social and economic inequality important to enable future-oriented political engagement from as many people as possible?

Democratic participation requires the capacity to see the present from the perspective of an imagined better future. But that presupposes the time and capacity for reflection. Those living in insecure conditions typically lack the resources and inclination to turn their eyes to the future. In exhausting jobs, the focus tends to be on getting through the day (or night): the present dominates the future. In precarious jobs or unemployment, people lack control of their lives: the future can look too unpredictable to bother with. Political engagement also depends on a sense that the problems encountered are shared with others. A workplace centred on short-term contracts on the contrary presents individuals with a constantly changing cast of peers. Other things can also undercut a sense of shared fate – personal debt, for instance, or algorithmic forms of scoring (eg, in insurance) that focus on the particularities of individual lives.

In exhausting jobs, the focus tends to be on getting through the day (or the night): the present dominates the future.

This is the sense in which the social and economic changes of the last few decades have fostered the privatisation of the future. The choices of political organisations like parties and movements are crucial in this context. They can either challenge these tendencies, developing that critical perspective on the present and a sense of shared fate – think eg, of a movement like the Debt Collective. Or they can reproduce these tendencies – eg, by treating voters as individuals who want only to maximise their own interests.

Q: What effects can crises have on how governments and citizens conceptualise and act on the future? Are current democratic political systems capable of addressing the climate crisis, the great future-oriented challenge of our time?

Crises tend to engender a sense of scarce time, and in the contemporary state that tends to bring a managerial approach to the fore. Emergencies are governed as one more problem of calculation, with a focus on concrete outcomes that can be traced from the present. The risk is that questions of justice and structural change get marginalised, as considerations that distract from the immediacy of the situation and open too many issues. Emergency government tends to prioritise short-term goals over long-term, and those which are concrete and quantifiable over those which are not.

Climate change too tends to be turned into a problem of calculation in policymaking circles. One sees it with the targets and deadlines invoked. By making net zero carbon emissions an overriding objective, authorities can marginalise considerations no less relevant to human wellbeing and environmental protection – biodiversity, global health and economic equality, for example. This is why some climate scholars see such methods as counterproductive. By emphasising a particular set of variables within a delimited timeframe, targets and deadlines get us thinking more about the near future, crowded with specificities, and less about the further horizon and the more general, incalculable goals that belong to it.

Taking the future seriously meant not hemming oneself in with false precision but setting out clear principles and organising in their pursuit.

The pitfalls of exactitude are something I try to highlight in the book. Not only is it hard to make predictions in a volatile world, but a focus on quantified targets can be counterproductive, since the facts at any moment can be bleak. As the socialists of the late 19th century understood, if the future was to be about radical change pursued over the long term, one could not afford to get lost in the details of the moment. Taking the future seriously meant not hemming oneself in with false precision but setting out clear principles and organising in their pursuit. I think this is a message that still applies. Climate change requires science and precision to grasp, but climate politics requires balancing this with a sense of uncertainty, open-endedness, and the possibility of radical change.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Anna D’Alton, Managing Editor of LSE Review of Books.

How To Write A Philosophy Paper: Online Guides

Some philosophy professors, realizing that many of their students are unfamiliar with writing philosophy papers, provide them with “how-to” guides to the task.

[Originally posted on January 15, 2019. Reposted by reader request.]

I thought it might be useful to collect examples of these. If you know of any already online, please mention them in the comments and include links.

If you have a PDF of one that isn’t online that you’d like to share, you can email it to me and I can put in online and add it to the list below.

Guidelines for Students on Writing Philosophy Papers

- “Guidelines on Writing a Philosophy Paper” by Jim Pryor

- “Writing a Good Philosophy Paper” by Justin Weinberg

- “Writing a Philosophy Paper” by Peter Horban

- “Tips on Writing Philosophy Papers” by William Blattner

- “How to Write (not Terrible) Philosophy Papers” by Manuel Vargas

- “Philosophy Paper Writing Guidelines” by Tim O’Keefe and Anne Farrell

- “A Guide to Writing” by Michael Huemer

- “Guidelines on Writing a Philosophy Paper” by Stephen Yablo

- “7 Steps to a Better Philosophy Paper” by Bryan W. Roberts

- “Some Writing Tips for Philosophy” by Brian Earp

- “How to Write a Crap Philosophy Essay” by James Lenman

- “A Sample Philosophy Paper” by Angela Mendelovici

- “Writing Philosophy Essays” by Michael Tooley

- “Writing Your Philosophy Paper: Common Problems to Avoid” by Elijah Millgram

- “A Guide to Philosophical Writing” by Elijah Chudnoff

- “The Pink Guide to Philosophy” by Helena de Bres

(Crossed-out text indicates outdated link.)

The post How To Write A Philosophy Paper: Online Guides first appeared on Daily Nous.

Is There A Sound Philosophical Method? (guest post)

“Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal?”

That is the question taken up in this guest post by John Bengson (University of Texas at Austin), Terence Cuneo (University of Vermont), and Russ Shafer-Landau (University of Wisconsin).

It is based on part of their book, Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (2022, Oxford University Press).

* * *

[James Welling, “7690” (detail)]

Is There A Sound Philosophical Method?

by John Bengson, Terence Cuneo, and Russ Shafer-Landau

It’s a striking fact about contemporary philosophy that different subfields privilege different methods. If you ask moral philosophers for their preferred method, you’re likely to get an earful about reflective equilibrium. Metaphysicians will probably sound off about theoretical virtues or how to weigh costs and benefits. Epistemologists tend to favor the method of cases and conceptual analysis, propelled by thought experiments and counterexamples, or perhaps an ameliorative variant guided by socio-political aspirations. There are also divisions within subfields (think, for instance, of differing approaches in philosophy of mind), along with fealty to particular methods associated with specific schools or traditions: phenomenology, ideological critique, hermeneutics, deconstruction, and so on. Aiming to find unity amidst this apparent diversity, some have claimed that flying at a higher altitude reveals all of philosophy to employ “the method of argument.”

Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal? We as a community are called to face this question together.

The first step is to clarify the goal. Setting aside philosophy’s legitimate practical and aesthetic aims (fortifying one’s soul, promoting justice, appreciating beauty), philosophy in its theoretical mode has many proper alethic and epistemic goals. These include truth, justified belief, and knowledge. But in our view none of these is theoretical philosophy’s ultimate proper goal, conceived as that state in which the questions that open inquiry are fully resolved—there is no more work to be done. That point is reached only with a theory that is not just highly accurate, coherent, and reason-based, but also yields the sort of broad, systematic illumination characteristic of understanding. A sound method supplies this good.*

Familiar methods fall short. For instance, no matter their plausibility or soundness, analyses and arguments are by themselves insufficient to guarantee the sort of explanatory illumination at issue. Weighing up costs and benefits may select for a theory that entirely fails to secure one or more of the understanding-providing features, including illumination, so long as the attendant benefits (such as simplicity) are deemed sufficiently virtuous. Nor will reflective equilibrium do the trick, as it permits theorists whose judgments and principles conflict to relinquish an understanding-providing feature, such as illumination or breadth, whenever doing so will reinstate balance. Moreover, even in its “wide” form, reflective equilibrium notoriously fails to put inquirers on track to achieve even a modicum of accuracy.

In a way, none of this should come as a surprise. After all, these methods weren’t crafted with understanding in mind. It’d be rash to label them failures or declare them useless. Following them faithfully may well yield other important achievements: truth, justified belief, or even knowledge. But we’re on the hunt for a sound method. So we need to keep looking.

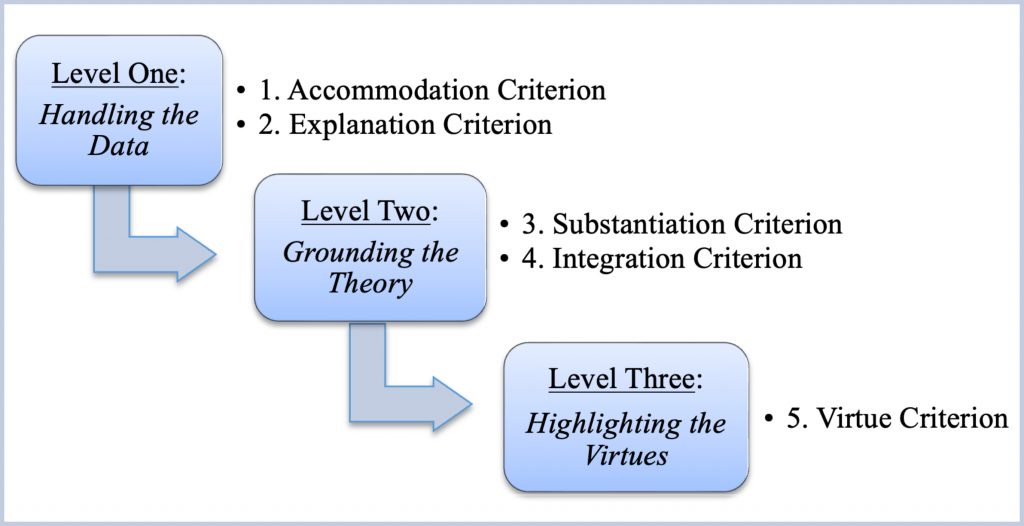

Here’s a sketch of the “Tri-Level Method” we propose in our recent book, Philosophical Methodology. As its name implies, the method incorporates a set of criteria at three levels. The first instructs theorists to handle the data associated with the topic they are inquiring about. The second tells theorists to ground all the claims they made when handling the data, as well as any further claims advanced when pursuing that grounding project. The third, enlisted only as a tie-breaker among theories that do roughly equally well at levels one and two, calls on theorists to develop their theories so as to exemplify specific theoretical virtues. The following diagram visually depicts their organization:

Let’s break this down more concretely. Our leading thought is that any sound method must take the data very seriously. There’s no theory without data. What are data? Roughly, they are inquiry-constraining starting points that serve as “common currency” for theoretical inquiry—not in the sense of being uncontroversial, but in the sense of meriting attention from theorists of all stripes. This is not a counsel of conservatism. Data are defeasible. Theorists may with perfect propriety reject one or more of them. But it is incumbent on theorists who do so to defend that rejection.**

At its first level, the Tri-Level Method consists of two criteria that instruct theorists on how to handle the data. The first criterion says that a theory must accommodate the data, rendering them likely; or it must adequately defend the claim that any such accommodation is unnecessary. The second criterion says that a theory must explain the data, saying why they hold; or it must adequately defend the claim that those data needn’t be explained.

The claims enlisted to perform these tasks are not self-standing. They must be defended, explained, and integrated in order for the theory that incorporates them to have a chance at facilitating understanding. This is the work assigned to theorists at the second level, which also comprises two criteria. The first of these calls on theorists to substantiate all of a theory’s constituent claims. In our book, substantiation amounts to defense (= offering a positive argument for) plus explanation. If a theorist declines to defend or explain a given element of her theory, she must adequately argue that such defenses or explanations are unnecessary (say, because a given claim is inexplicable). Further—and this is the second criterion at level two—all of the claims in a theory must either be integrated with both one another and our best picture of the world (which includes the deliverances of our best science), or be exempted from this stricture via a compelling argument for the acceptability of the resulting incoherence.

That’s a lot of work. If (and only if) two or more theories are roughly on par with respect to the criteria at levels one and two, theorists are instructed, at level three, to make their views as virtuous as possible—where something is a theoretical virtue just if its realization by a theory contributes to understanding. Simplicity might play this role; we ourselves are neutral. Yet the question is hardly pressing, since in practice it may be the rare occasion when a theorist has any call to advance to this third level.

It might be helpful to collect the five criteria, which amount to norms of theoretical inquiry, together in one place:

Accommodation Criterion: Accommodate the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Explanation Criterion: Explain the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Substantiation Criterion: Defend and explain the theory’s claims, or adequately defend not doing so.

Integration Criterion: Integrate the theory’s claims with each other and our best picture of the world, or adequately defend not doing so.

Virtue Criterion: Make the theory’s claims more theoretically virtuous than rivals, all else being equal.

Although the method does not say the criteria must be satisfied in this order, the list traces a natural progression from data to theory.

There are a few routes to defending the Tri-Level Method. One emphasizes that its criteria are constitutively connected to the understanding-providing features we encountered above. At the first level: accommodating data is keyed into accuracy; explaining them ensures illumination. By jointly doing these things with respect to a wide range of data, the theory becomes more robust, achieving breadth. At the second level: defending a theory’s claims guarantees that it is reason-based; explaining those claims extends and deepens the illumination it provides. If a theory’s claims are internally well-integrated, it will achieve coherence and, on the assumption that our best picture of the world is in decent shape, external integration offers the promise of greater accuracy. By satisfying all four of these criteria together, a theory is also poised to be orderly, hence systematic. At the third level: should two or more theories fare roughly equally well at levels one and two, we can assess their relative merits by attending to the virtues they exemplify. At this level, too, there is a constitutive link to understanding, since we defined theoretical virtues in terms of their ability to facilitate that very epistemic achievement when the first four criteria have been satisfied.

The foregoing supports viewing the method as sound. There is more to say. For instance, the Tri-Level Method is not only friendly to the various activities in which philosophers engage when they’re doing philosophy:

- advancing arguments

- raising objections

- offering replies to these objections

- providing clarification

- developing explanations (with miscellaneous virtues)

- displaying sensitivity to the deliverances of science, mathematics, and logic.

The method also explains why it is a good thing for philosophers to engage in these activities: doing so conduces to the satisfaction of the method’s criteria (which, again, are constitutively linked to philosophy’s ultimate proper goal). Moreover, it achieves this explanation while also making sense of the attractions of familiar methods. Although their directives don’t point all the way to understanding, they’re arguably attuned to one or more of the method’s five criteria.

Yet conforming to the Tri-Level Method would not be to engage in business as usual. For one thing, it calls upon each theory to handle the full range of data: no cherry-picking! It also instructs theorists to develop their views as well and fully as they can, rather than simply to exchange arguments and objections with their rivals—as sometimes happens when theorists merely shift burdens of proof, or fixate on admissible moves within a given dialectic. Further, the method advises attention to the data while discouraging undue emphasis on parsimony and other putative theoretical virtues that should play only a tie-breaking role late in the game. The method’s criteria help keep theorists’ eyes on the prize.

The Tri-Level Method is not revolutionary. Its answer to the question of method incorporates bits of wisdom from extant methods, which enjoy popularity in one or another subfield. Its elements are also familiar from the way most philosophers ply their trade. Still, the specific instructions it contains, their rationale, and the order of operations it suggests strike us as offering a promising path to attaining theoretical understanding and, consequently, to making philosophical progress.***

notes:

* This paragraph is a very brief sketch of ideas and arguments about the structure and goals of inquiry in Chapter One of our Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (OUP, 2022), on which the whole of this post is based.

** We’ve noted some data about data. What theory best handles these metadata? Chapter Two critically discusses sociological, metaphysical, psychological, and linguistic theories of data. Chapter Three develops an alternative, epistemic theory of data, centering on the notion of a pretheoretical consideration that inquirers considered collectively have good epistemic reason to believe.

*** Chapter Six is dedicated to the matter of philosophical progress, elucidating the role of the Tri-Level Method therein.

The post Is There A Sound Philosophical Method? (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

The one doctrine state

This is a highly interesting article by Abby Innes on her recent book, provocatively titled ‘Late Soviet Britain’. This is really remarkably good stuff: She has concluded that the neoliberal state is based on an axiom (where axiom indicates an idea that is blindly accepted without any proof – and as a basis for argument).... Read more

Language and the Rise of the Algorithm – review

In Language and the Rise of the Algorithm, Jeffrey Binder weaves together the past five centuries of mathematics, computer science and linguistic thought to examine the development of algorithmic thinking. According to Juan M. del Nido, Binder’s nuanced interdisciplinary work illuminates attempts to maintain and bridge the boundary between technical knowledge and everyday language.

Language and the Rise of the Algorithm. Jeffrey Binder. The University of Chicago Press. 2023

Arguably, the history of what we now call algorithmic thinking is also the history of the consolidation of algebra, mathematics, calculus and formal logic as tools for composing, enunciating, and thinking about abstractions such as “some flowers are red”. But in less obvious ways, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm shows, it is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world. In other words, it is the history of ensuring that “red” actually means red – that we are all clear on who sets what red means (for example, experts through definition or ordinary people through usage) and agree on it – and of whether agreeing about these things is what matters when we use language.

Arguably, the history of what we now call algorithmic thinking is also the history of the consolidation of algebra, mathematics, calculus and formal logic as tools for composing, enunciating, and thinking about abstractions such as “some flowers are red”. But in less obvious ways, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm shows, it is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world. In other words, it is the history of ensuring that “red” actually means red – that we are all clear on who sets what red means (for example, experts through definition or ordinary people through usage) and agree on it – and of whether agreeing about these things is what matters when we use language.

The history of what we now call algorithmic thinking […]is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world.

Harking back to the 1500s, the first of the book’s five chapters examines attempts to use symbols to free writing from words at a time when vernaculars where plentiful, grammars unstable and literacy rates low. Algebra was not then considered part of mathematics proper but its rules, expressed in spoken language, were used for practical purposes like calculating taxes and inheritance. From myriad writing experiments emerged algebraic symbols: uncertain and indeterminate, they enabled computational reasoning about unknown values, a revolution that peaked when Viète first used letters in equations in 1591 (33-36).

Algebra was not [In the 1500s] considered part of mathematics proper but its rules, expressed in spoken language, were used for practical purposes like calculating taxes and inheritance

Chapter Two explores Leibniz’s attempts to produce a philosophical language made of symbols and unburdened by words, such that morals, metaphysics, and experiences are all subject to calculation. This was not an exercise in spitting out numbers, but with the aim of demonstrating the reasoning behind every step of communication: a truth-producing machine (62-64). The messiness of communication struck back: how can one ensure that all terms and their nuances are understood in the same way by different people? Leibniz argued that knowledge was divinely installed in us, waiting to be unlocked by devices such as his, but Locke’s argument that knowledge comes from sensory experience and requires an agreement over what things mean won the day (79), paving the way towards an emphasis on concepts and form.

Leibniz argued that knowledge was divinely installed in us, waiting to be unlocked […] but Locke’s argument that knowledge comes from sensory experience and requires an agreement over what things mean won the day

Leibniz also sought to resolve political differences through that language. Chapter Three argues Condorcet shared this goal and the premise that vernaculars were a hindrance, but contrary to Leibniz, he believed universal ideas needed to be taught, not uncovered. Condillac’s and Stanhope’s experiments with other logical machines – actual, material devices designed to think in logical terms through objects – epitomised two tensions framing the century after the French Revolution: first, the matter of whether the people, and their vernacular culture, or the learned, and their enlightened culture, should govern shared meanings – that is to say, give meaning – and second, whether algebra should focus on philosophical and conceptual explanations or on formal definitions and rules (121).

The latter drive would prevail, and as Chapter Four shows, rigour came to emanate not from verbal definitions or clarity of meanings, but from axiomatic systems judged on consistency: meanings are irrelevant to the formal rules by which the system operates (148). Developing this consistency would not require the complete replacement of vernaculars Leibniz and Condorcet argued for: rather, symbolic forms would work alongside vernaculars to produce truth values, as with Boolean logic – the one powering search engines, for example. The fifth and last chapter, “Mass Produced Software Components”, rise of programming languages, in particular ALGOL, and the consolidation of regardless of specifics: intelligible, actionable results within a given amount of time (166).

Binder’s rigorous dissection of debates over language, philosophy, geometry, algebra, history and culture spanning 500 years integrates debates that most disciplines today, aside from some strands of media studies and Science and Technology Studies, tend to treat separately

This book is a tightly packed, erudite contribution to the growing concern in the Humanities with algorithms. Binder’s rigorous dissection of debates over language, philosophy, geometry, algebra, history and culture spanning 500 years integrates debates that most disciplines today, aside from some strands of media studies and Science and Technology Studies, tend to treat separately or with a poor sense of their inbuilt connections. A welcome result of this exercise is the historicisation of certain critiques of technological interventions in politics that, generally lacking this kind of integrated, long-range view, we tend to treat as novel and cutting-edge. For example, an 1818 obituary for Charles Mahon, third Earl of Stanhope and inventor of the Demonstrator, a “reasoning machine”, already claimed that technical solutions for other-than-technical problems such as his tend to replicate the biases of their creators (113), and often the very problems they intended to solve. This critique of technoidealism is now commonplace in the social sciences.

A second benefit of the author’s mode of writing is not explicit in the book but is arguably more consequential. From Bacon’s dismissal of words as “idols of the market” in 1623 (15) to PageRank algorithm’s developers’ goal to remove human judgement by mechanisation in the 1990s (200), the book traces attempts across the centuries to free reason and knowledge from language and rhetoric. In doing this, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm effectively serves as a highly persuasive history of the affects, ethics and aspirations of technocratic reason and rule. The book cuts across the histories of bureaucracy and expertise and the birth of governmentality to tell us how an abstraction in how we make meaning work emerged – an abstraction we are asked to trust in, and argue for, partly because it is the kind of abstraction it ended up being.

The book traces attempts across the centuries to free reason and knowledge from language and rhetoric

This is a rich and nuanced book, at times encyclopaedic in scope, and except for a slight jump in complexity and some jargon in the fifth and last chapter, it will be accessible to readers lacking prior knowledge of algorithms, mathematics or language philosophy. It will be of interest to scholars across the social sciences and humanities, from philosophy and history to sociology and anthropology, as well as readers in political science, government studies and economics for the reasons listed above. It could work as course material for very advanced students.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Lettuce. on Flickr.

The Plastic Turn – review

In The Plastic Turn, Ranjan Ghosh posits plastic as the defining material of our age and plasticity as an innovative means of understanding the arts and literature. Joff Bradley welcomes this innovative philosophical treatise on how we can make sense of the modern world through a plastic lens.

The Plastic Turn. Ranjan Ghosh. Cornell University Press. 2022.

There are few books nowadays in which you can find expansive discussions on everything from the aesthetics of polymers and molecules, Indian poetics, and sculpture, to the lineage Umberto Eco-Aristotle-Dante-Kant-Borges-Foucault-Deleuze. Not only that, but this fine book for humanities students and scholars juxtaposes crystalline structures, thermoplastics and thermosetting, alongside treaties on critical thinking, T. S. Eliot, the poetics of flow and globalisation, the non-metaphorical nature of plastic, as well as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) and Indian philosophy.

There are few books nowadays in which you can find expansive discussions on everything from the aesthetics of polymers and molecules, Indian poetics, and sculpture, to the lineage Umberto Eco-Aristotle-Dante-Kant-Borges-Foucault-Deleuze. Not only that, but this fine book for humanities students and scholars juxtaposes crystalline structures, thermoplastics and thermosetting, alongside treaties on critical thinking, T. S. Eliot, the poetics of flow and globalisation, the non-metaphorical nature of plastic, as well as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) and Indian philosophy.

The way Ghosh’s book does this so cleverly throughout is to ask after the nature of plastic and, well, the very plasticity of the term. Ghosh structures the book in a manner that combines free-flowing exploration with organised thematic sections. The narrative moves seamlessly between different ideas and works of literature, creating a dynamic reading experience which moulds the intellect. Additionally, the book is divided into sections, each with specific themes concerning plasticity (turning, the literary, tough, literature, affect) that provide a structured framework for understanding the diverse range of topics covered.

Ghosh asks his readers: How has plastic come to infiltrate so many aspects of our everyday lives, and why must we turn or bend toward it?

Ghosh asks his readers: How has plastic come to infiltrate so many aspects of our everyday lives, and why must we turn or bend toward it? For many readers, this may not be a question that usually springs to mind, but once we immerse ourselves in Ghosh’s prose, we learn that the plasticity of “plastic” has a versatile reach and applicability, as it allows us to explore the aesthetics of material and materialist aesthetics.

The book is not a straightforward, inflexible treatise on environmental waste pollution per se, though it does nevertheless touch upon ecological issues; rather, its stance is something akin to a philosophical material science of plastic. It is more aesthetico-ecological in that sense. A key trope is the materiality of plastic, its codification, its expressive potential, its inspiration. And with this, the turn to plastic raises our eyes to its futural possibility. What can plastic do to transform the world, to mould and conjure new futures?

Thinking can never be without plastic material. Plastic matters in its materiality, in its affective-aesthetic power, in its technology.

What we learn much about from this mould-breaking (iconocl(pl)astic) book is the plasticity of poetry and how we must address language as the house of being’s plasticity, to reshape Heidegger’s words. Indeed, thinking can never be without plastic material. Plastic matters in its materiality, in its affective-aesthetic power, in its technology. Plastic offers a new sensibility and sensitivity. Plastic makes us think of moulding and malleability and the possibility of infinite shapes and forms, the nth degree of concepts. As the author says, plastic remodels, crafts and carves thinking, habits, lifestyles, emotions, economy, and passion. Ghosh shows the asymmetric connection between the material of plastic and the aesthetic and makes a pathway from denotation to deduction, to representation, and to asymmetry because, for him, plastic is such a malleable material form.

The materiality of plastic shows this through its dimensions of visibility, the haptic, the figure. And so, as we come to understand the way that plastic softens and solidifies, moulds and remoulds; we learn of the aesthetic hidden in the material; how the structures of plastic can be transferred to the structures of poetry and literature; and how material crystalline natures are somehow expressed in the crystalline textuality of poetry. The plastic offers new readings, joins chains of meaning and bonds ideas together, demonstrating that poetry, philosophy, language and literature are megamolecules or polymer in nature, in the way they open themselves to multiple interpretations, different meanings. Plastic helps us to understand the flow and movement of text, to understand, how plastic’s lubricity can be passed on to the text itself, how “plasticisers” open up the text, disturbing its stasis.

The plasticity of text doesn’t mean anarchy or structurelessness, because plasticity functions through plasticisers. This is how and where something can begin to gel, to take on form, structure, meaning

But more than this, the plasticity of text doesn’t mean anarchy or structurelessness, because plasticity functions through plasticisers. This is how and where something can begin to gel, to take on form, structure, meaning. Meaning-making is only possible with and through the operations of the plasticisers of the text. As Ghosh brilliantly shows, The Waste Land is PVC; it has its own polymeric status. Without the plasticisers, poetry would be rigid and strict in its meaning-making abilities. What this book so cleverly contends is that plastic’s formation and deformation not only suggest the endless remodelling of the term, but the very meta-modelisation or meta-moulding of the concept, that is, creating models that represent other models with the task of revealing new radical and revolutionary potentials.

Plastic has ‘unmade us’ and ‘ungrounded’ us, and the way we think, express, and love. Plastic gives sense to the question of new modes of extinction.

The qualities of plastic – durability, flexibility, and moldability, cohesiveness and consistency – suggest that the concept will linger and outlast us all. We need to know this, because as the author argues, we moderns have already unconsciously embraced deep forms of plasticity. The author adds to this description by suggesting that plastic is inherently connected with the quest of modernity, that it is essentially disruptive and oppositional. And now, in this time of the plastisphere and the plasticene, and with the Earth encrusted and entangled in plastic, and as plastitrash abounds, the concept should not be without criticism. We come to appreciate Ghosh’s congeries of performatives: the thanatopoetics (or death-poetics) of plastic, “the history of our inheritance,” the way plastic has “unmade us” and “ungrounded” us, and the way we think, express, and love. Plastic gives sense to the question of new modes of extinction. Plastic discloses the life-in-death of humankind. As Ghosh says, contorts the image of humankind: “[P]lastic has stunned the anthropos, threatening to morph them within a circuit where human comes to surprise human” (36).

With seas already full of plastic, a book like Ghosh’s demands that we open ourselves up to the concept of plasticity in the hope of transforming, remodelling another way to be

With seas already full of plastic, a book like Ghosh’s demands that we open ourselves up to the concept of plasticity in the hope of transforming, remodelling another way to be, to speak, to think, to see, and to feel. The future is plastic, bendable but not breakable. This is the hope of Ghosh’s methodology. The book in this respect sets out a new language, a new code and discipline; indeed, it demands a new politico-philosophical vision and for this reason, it is an original and worthwhile reading experience for all those concerned with the humanities, the Anthropocene, the written word and the ecology of good and bad ideas. Ghosh’s Plastic Turn not only breaks the mould of literary criticism but asks others to refashion critical literature in elastic, versatile and plastic ways.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Serrgey75 on Shutterstock.