aesthetics

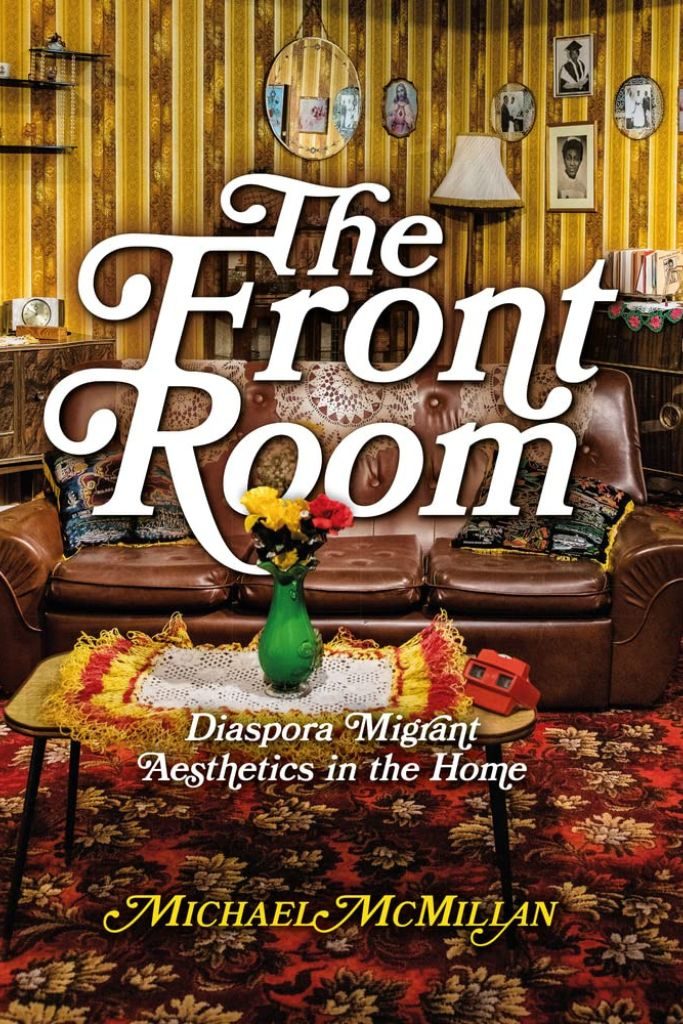

The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home – review

In The Front Room, Michael McMillan examines the significance of domestic spaces in creating a sense of belonging for Caribbean migrants in the UK. Delving into themes of resistance and creolisation, these sensitively curated essays and images reveal how ordinary objects shape diasporic identities, writes Antara Chakrabarty.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves.

The book takes us on a journey of discovery as to what spaces meant, looked, smelled and felt like for Caribbean diaspora settled in the UK from the mid-20th century. It describes how the tactile sensations and emotions held in a room amount to so much more than its aesthetics. The text begins with a section on how Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves. The images used to showcase the different varieties of such front rooms were mostly taken from the response to the exhibition, A front room in 1976 , curated by McMillan at the Museum of the Home in London in 2005-06.

A primary thematic focus is the emergence of a significant cultural process of change often called as creolisation which gives rise to a third culture which is neither Caribbean, nor British, but a diasporic intermingling of the two. This creolisation also occurs as a result of intergenerational change in the wake of World War Two and apartheid. Moreover, it speaks to the changing imagination around what can be called a “home”, reflecting changes in identity in a foreign land. The lucidity of the essays and the various references to sociological and anthropological works on the perception of “self”, vis-à-vis place making like those by Erving Goffman, Emile Durkheim, Stuart Hall gears the book towards students beyond the disciplinary boundaries of Sociology, Anthropology, Arts and Aesthetics, History, Museology and more. Towards the latter part of the book, McMillan also brings in other diasporic communities beyond the Caribbean, such as Moroccan, Surinamese, Antillean and Indonesian migrant communities in the Netherlands.

Front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community.

The book presents an important diasporic narrative underpinned by a critical struggle of the diasporic experience: underneath the subject of the ”front room” lies the process of subverted diasporic emotions and anti-assimilation cultural change. The emotional attachments are prioritised over fitting exactly within the typical British space. McMillan presents his readers with ten commodities that were normally seen in the Caribbean households which were also seen in the diasporic “front room” in the UK. These objects wordlessly communicated the Caribbean way of life without. A homogenisation of the objects found in the across the British Caribbean front room happened gradually as people visited one another, trying to emulate the aesthetics of a diasporic migrant culture. As someone from South Asia, I can vouch fora very similar pattern post-colonisation. Some chose to keep religious symbolic items at the forefront whereas the others chose to fit into the moral definition of aesthetics according to the British. A front room could become a Durkheimian quasi-sacred space which had to be seen beyond its mundane nature. McMillan emphasises the changes across generations and how front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community. The book makes its readers aware of the significance contained in the spaces not just through imagery, but also literary compositions like songs, poems, and other varieties of literature.

The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes.

The book describes the affective power of objects through ten examples including the paraffin heater, which gave a sense of reassurance and reminded migrants of their homes through the scent of paraffin oil. The radiogram (a piece of furniture that combined a radio and record player) played the role of “home” in another new land, a sonic gateway into the past. Several other items also acted in service of what Goffman would call ‘impression management’ to a larger audience. The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes. Notably, the carpets and wallpapers, though quintessentially British in theory, could be reclaimed and subverted through the choice of colourful options rather than plain base colours. The book also captures the effects of technological evolution through the inclusion of televisions, telephones and pictures of revered role models such as politicians and singers on display.

McMillan’s work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

One may make the mistake of perceiving this text as an over-romanticisation of material objects that convey diasporic identity. However, McMillan avoids this, convincing his readers of the deeply felt significance of the ordinary in connecting diaspora to the places they left behind. He bolsters this through setting ordinary items, spaces and lives in the context of unique epistemological nuances such as apartheid, cultural hybridisation, symbolic capital, taste and more. His work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

The book is successful in its theatrical and thoughtful presentation and the depth it achieves over only a limited number of essays. Its effect is to fill readers’ minds with questions and to pave the way for similar studies in other postcolonial diasporic communities.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: 12matamoros on Pixabay

The Plastic Turn – review

In The Plastic Turn, Ranjan Ghosh posits plastic as the defining material of our age and plasticity as an innovative means of understanding the arts and literature. Joff Bradley welcomes this innovative philosophical treatise on how we can make sense of the modern world through a plastic lens.

The Plastic Turn. Ranjan Ghosh. Cornell University Press. 2022.

There are few books nowadays in which you can find expansive discussions on everything from the aesthetics of polymers and molecules, Indian poetics, and sculpture, to the lineage Umberto Eco-Aristotle-Dante-Kant-Borges-Foucault-Deleuze. Not only that, but this fine book for humanities students and scholars juxtaposes crystalline structures, thermoplastics and thermosetting, alongside treaties on critical thinking, T. S. Eliot, the poetics of flow and globalisation, the non-metaphorical nature of plastic, as well as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) and Indian philosophy.

There are few books nowadays in which you can find expansive discussions on everything from the aesthetics of polymers and molecules, Indian poetics, and sculpture, to the lineage Umberto Eco-Aristotle-Dante-Kant-Borges-Foucault-Deleuze. Not only that, but this fine book for humanities students and scholars juxtaposes crystalline structures, thermoplastics and thermosetting, alongside treaties on critical thinking, T. S. Eliot, the poetics of flow and globalisation, the non-metaphorical nature of plastic, as well as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) and Indian philosophy.

The way Ghosh’s book does this so cleverly throughout is to ask after the nature of plastic and, well, the very plasticity of the term. Ghosh structures the book in a manner that combines free-flowing exploration with organised thematic sections. The narrative moves seamlessly between different ideas and works of literature, creating a dynamic reading experience which moulds the intellect. Additionally, the book is divided into sections, each with specific themes concerning plasticity (turning, the literary, tough, literature, affect) that provide a structured framework for understanding the diverse range of topics covered.

Ghosh asks his readers: How has plastic come to infiltrate so many aspects of our everyday lives, and why must we turn or bend toward it?

Ghosh asks his readers: How has plastic come to infiltrate so many aspects of our everyday lives, and why must we turn or bend toward it? For many readers, this may not be a question that usually springs to mind, but once we immerse ourselves in Ghosh’s prose, we learn that the plasticity of “plastic” has a versatile reach and applicability, as it allows us to explore the aesthetics of material and materialist aesthetics.

The book is not a straightforward, inflexible treatise on environmental waste pollution per se, though it does nevertheless touch upon ecological issues; rather, its stance is something akin to a philosophical material science of plastic. It is more aesthetico-ecological in that sense. A key trope is the materiality of plastic, its codification, its expressive potential, its inspiration. And with this, the turn to plastic raises our eyes to its futural possibility. What can plastic do to transform the world, to mould and conjure new futures?

Thinking can never be without plastic material. Plastic matters in its materiality, in its affective-aesthetic power, in its technology.

What we learn much about from this mould-breaking (iconocl(pl)astic) book is the plasticity of poetry and how we must address language as the house of being’s plasticity, to reshape Heidegger’s words. Indeed, thinking can never be without plastic material. Plastic matters in its materiality, in its affective-aesthetic power, in its technology. Plastic offers a new sensibility and sensitivity. Plastic makes us think of moulding and malleability and the possibility of infinite shapes and forms, the nth degree of concepts. As the author says, plastic remodels, crafts and carves thinking, habits, lifestyles, emotions, economy, and passion. Ghosh shows the asymmetric connection between the material of plastic and the aesthetic and makes a pathway from denotation to deduction, to representation, and to asymmetry because, for him, plastic is such a malleable material form.

The materiality of plastic shows this through its dimensions of visibility, the haptic, the figure. And so, as we come to understand the way that plastic softens and solidifies, moulds and remoulds; we learn of the aesthetic hidden in the material; how the structures of plastic can be transferred to the structures of poetry and literature; and how material crystalline natures are somehow expressed in the crystalline textuality of poetry. The plastic offers new readings, joins chains of meaning and bonds ideas together, demonstrating that poetry, philosophy, language and literature are megamolecules or polymer in nature, in the way they open themselves to multiple interpretations, different meanings. Plastic helps us to understand the flow and movement of text, to understand, how plastic’s lubricity can be passed on to the text itself, how “plasticisers” open up the text, disturbing its stasis.

The plasticity of text doesn’t mean anarchy or structurelessness, because plasticity functions through plasticisers. This is how and where something can begin to gel, to take on form, structure, meaning

But more than this, the plasticity of text doesn’t mean anarchy or structurelessness, because plasticity functions through plasticisers. This is how and where something can begin to gel, to take on form, structure, meaning. Meaning-making is only possible with and through the operations of the plasticisers of the text. As Ghosh brilliantly shows, The Waste Land is PVC; it has its own polymeric status. Without the plasticisers, poetry would be rigid and strict in its meaning-making abilities. What this book so cleverly contends is that plastic’s formation and deformation not only suggest the endless remodelling of the term, but the very meta-modelisation or meta-moulding of the concept, that is, creating models that represent other models with the task of revealing new radical and revolutionary potentials.

Plastic has ‘unmade us’ and ‘ungrounded’ us, and the way we think, express, and love. Plastic gives sense to the question of new modes of extinction.

The qualities of plastic – durability, flexibility, and moldability, cohesiveness and consistency – suggest that the concept will linger and outlast us all. We need to know this, because as the author argues, we moderns have already unconsciously embraced deep forms of plasticity. The author adds to this description by suggesting that plastic is inherently connected with the quest of modernity, that it is essentially disruptive and oppositional. And now, in this time of the plastisphere and the plasticene, and with the Earth encrusted and entangled in plastic, and as plastitrash abounds, the concept should not be without criticism. We come to appreciate Ghosh’s congeries of performatives: the thanatopoetics (or death-poetics) of plastic, “the history of our inheritance,” the way plastic has “unmade us” and “ungrounded” us, and the way we think, express, and love. Plastic gives sense to the question of new modes of extinction. Plastic discloses the life-in-death of humankind. As Ghosh says, contorts the image of humankind: “[P]lastic has stunned the anthropos, threatening to morph them within a circuit where human comes to surprise human” (36).

With seas already full of plastic, a book like Ghosh’s demands that we open ourselves up to the concept of plasticity in the hope of transforming, remodelling another way to be

With seas already full of plastic, a book like Ghosh’s demands that we open ourselves up to the concept of plasticity in the hope of transforming, remodelling another way to be, to speak, to think, to see, and to feel. The future is plastic, bendable but not breakable. This is the hope of Ghosh’s methodology. The book in this respect sets out a new language, a new code and discipline; indeed, it demands a new politico-philosophical vision and for this reason, it is an original and worthwhile reading experience for all those concerned with the humanities, the Anthropocene, the written word and the ecology of good and bad ideas. Ghosh’s Plastic Turn not only breaks the mould of literary criticism but asks others to refashion critical literature in elastic, versatile and plastic ways.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Serrgey75 on Shutterstock.

Why Does the Far Right Love a Pompadour?

Why do these politicians don big hair? Perhaps their inventively crafted manes serve to hide behind their bad ideas. Or maybe, like the pompadours of male entertainers, their big hair is the best way to be remembered by voters. Who can forget such hairdos?...

Questioning Art in a Time of War

Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah is nominally addressed to Jewish teens in the United States who are preparing for their B’nai Mitzvahs (a gender-neutral rendering of Bat or Bar Mitzvah). It was published in an edition of 3,000 by Wendy’s Subway, an independent Brooklyn publisher, with support from Harvard University and VCU, which places the book squarely within an art-world context. What, if anything, can this politically-oriented book accomplish in an art context that direct activism in organizations like JVP cannot?...

The Diasporic Quartets: Identity and Aesthetics

Keynote lecture in the Diversity and the British String Quartet Symposium, day 3, held on 16th June 2021. Part of the Humanities Cultural Programme, one of the founding stones for the future Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities. Chair: Dr Nina Whiteman

Speaker: Dr Des Oliver

On our final day, we begin with a keynote lecture from composer Dr Des Oliver on his ‘Diasporic Quartets’ projects.

You can learn more here https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/diversity-and-the-british-string-quartet-0#/

What is the Modern? Temporality, Aesthetics, and Global Melancholy

This talk from TORCH Global South Visiting Professor Supriya Chaudhuri will interrogate the temporality of the modern, the aesthetics of the modern, and as a somewhat cryptic afterthought, the mood of the modern, here categorized as melancholy. But it will also ask how this term travels, how it is translated between cultures, and what it means in specific contexts of use.

The terms ‘modern’ and ‘modernity’ are notorious, global itinerants, on the one hand associated with a narrative of power, and on the other with a profoundly asymmetrical reading of history, producing its own internal disjuncture through the tendency of ‘aesthetic modernity’ to deny or refuse history, and to produce a characteristic, melancholic, ‘hollowing-out’ of the world of technological modernization.

How are these terms, and the narratives associated with them, read back in contexts of translation or re-use? Professor Chaudhuri will look at some examples from 19th and 20th century India to examine how the term ‘modern’ is translated, understood, and incorporated into aesthetic and social practice.