Is There A Sound Philosophical Method? (guest post)

“Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal?”

That is the question taken up in this guest post by John Bengson (University of Texas at Austin), Terence Cuneo (University of Vermont), and Russ Shafer-Landau (University of Wisconsin).

It is based on part of their book, Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (2022, Oxford University Press).

* * *

[James Welling, “7690” (detail)]

Is There A Sound Philosophical Method?

by John Bengson, Terence Cuneo, and Russ Shafer-Landau

It’s a striking fact about contemporary philosophy that different subfields privilege different methods. If you ask moral philosophers for their preferred method, you’re likely to get an earful about reflective equilibrium. Metaphysicians will probably sound off about theoretical virtues or how to weigh costs and benefits. Epistemologists tend to favor the method of cases and conceptual analysis, propelled by thought experiments and counterexamples, or perhaps an ameliorative variant guided by socio-political aspirations. There are also divisions within subfields (think, for instance, of differing approaches in philosophy of mind), along with fealty to particular methods associated with specific schools or traditions: phenomenology, ideological critique, hermeneutics, deconstruction, and so on. Aiming to find unity amidst this apparent diversity, some have claimed that flying at a higher altitude reveals all of philosophy to employ “the method of argument.”

Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal? We as a community are called to face this question together.

The first step is to clarify the goal. Setting aside philosophy’s legitimate practical and aesthetic aims (fortifying one’s soul, promoting justice, appreciating beauty), philosophy in its theoretical mode has many proper alethic and epistemic goals. These include truth, justified belief, and knowledge. But in our view none of these is theoretical philosophy’s ultimate proper goal, conceived as that state in which the questions that open inquiry are fully resolved—there is no more work to be done. That point is reached only with a theory that is not just highly accurate, coherent, and reason-based, but also yields the sort of broad, systematic illumination characteristic of understanding. A sound method supplies this good.*

Familiar methods fall short. For instance, no matter their plausibility or soundness, analyses and arguments are by themselves insufficient to guarantee the sort of explanatory illumination at issue. Weighing up costs and benefits may select for a theory that entirely fails to secure one or more of the understanding-providing features, including illumination, so long as the attendant benefits (such as simplicity) are deemed sufficiently virtuous. Nor will reflective equilibrium do the trick, as it permits theorists whose judgments and principles conflict to relinquish an understanding-providing feature, such as illumination or breadth, whenever doing so will reinstate balance. Moreover, even in its “wide” form, reflective equilibrium notoriously fails to put inquirers on track to achieve even a modicum of accuracy.

In a way, none of this should come as a surprise. After all, these methods weren’t crafted with understanding in mind. It’d be rash to label them failures or declare them useless. Following them faithfully may well yield other important achievements: truth, justified belief, or even knowledge. But we’re on the hunt for a sound method. So we need to keep looking.

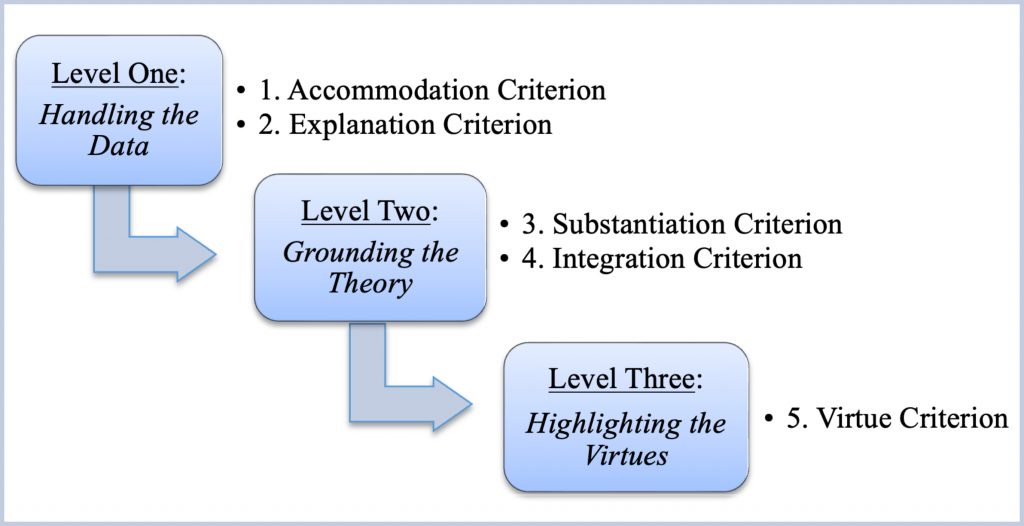

Here’s a sketch of the “Tri-Level Method” we propose in our recent book, Philosophical Methodology. As its name implies, the method incorporates a set of criteria at three levels. The first instructs theorists to handle the data associated with the topic they are inquiring about. The second tells theorists to ground all the claims they made when handling the data, as well as any further claims advanced when pursuing that grounding project. The third, enlisted only as a tie-breaker among theories that do roughly equally well at levels one and two, calls on theorists to develop their theories so as to exemplify specific theoretical virtues. The following diagram visually depicts their organization:

Let’s break this down more concretely. Our leading thought is that any sound method must take the data very seriously. There’s no theory without data. What are data? Roughly, they are inquiry-constraining starting points that serve as “common currency” for theoretical inquiry—not in the sense of being uncontroversial, but in the sense of meriting attention from theorists of all stripes. This is not a counsel of conservatism. Data are defeasible. Theorists may with perfect propriety reject one or more of them. But it is incumbent on theorists who do so to defend that rejection.**

At its first level, the Tri-Level Method consists of two criteria that instruct theorists on how to handle the data. The first criterion says that a theory must accommodate the data, rendering them likely; or it must adequately defend the claim that any such accommodation is unnecessary. The second criterion says that a theory must explain the data, saying why they hold; or it must adequately defend the claim that those data needn’t be explained.

The claims enlisted to perform these tasks are not self-standing. They must be defended, explained, and integrated in order for the theory that incorporates them to have a chance at facilitating understanding. This is the work assigned to theorists at the second level, which also comprises two criteria. The first of these calls on theorists to substantiate all of a theory’s constituent claims. In our book, substantiation amounts to defense (= offering a positive argument for) plus explanation. If a theorist declines to defend or explain a given element of her theory, she must adequately argue that such defenses or explanations are unnecessary (say, because a given claim is inexplicable). Further—and this is the second criterion at level two—all of the claims in a theory must either be integrated with both one another and our best picture of the world (which includes the deliverances of our best science), or be exempted from this stricture via a compelling argument for the acceptability of the resulting incoherence.

That’s a lot of work. If (and only if) two or more theories are roughly on par with respect to the criteria at levels one and two, theorists are instructed, at level three, to make their views as virtuous as possible—where something is a theoretical virtue just if its realization by a theory contributes to understanding. Simplicity might play this role; we ourselves are neutral. Yet the question is hardly pressing, since in practice it may be the rare occasion when a theorist has any call to advance to this third level.

It might be helpful to collect the five criteria, which amount to norms of theoretical inquiry, together in one place:

Accommodation Criterion: Accommodate the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Explanation Criterion: Explain the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Substantiation Criterion: Defend and explain the theory’s claims, or adequately defend not doing so.

Integration Criterion: Integrate the theory’s claims with each other and our best picture of the world, or adequately defend not doing so.

Virtue Criterion: Make the theory’s claims more theoretically virtuous than rivals, all else being equal.

Although the method does not say the criteria must be satisfied in this order, the list traces a natural progression from data to theory.

There are a few routes to defending the Tri-Level Method. One emphasizes that its criteria are constitutively connected to the understanding-providing features we encountered above. At the first level: accommodating data is keyed into accuracy; explaining them ensures illumination. By jointly doing these things with respect to a wide range of data, the theory becomes more robust, achieving breadth. At the second level: defending a theory’s claims guarantees that it is reason-based; explaining those claims extends and deepens the illumination it provides. If a theory’s claims are internally well-integrated, it will achieve coherence and, on the assumption that our best picture of the world is in decent shape, external integration offers the promise of greater accuracy. By satisfying all four of these criteria together, a theory is also poised to be orderly, hence systematic. At the third level: should two or more theories fare roughly equally well at levels one and two, we can assess their relative merits by attending to the virtues they exemplify. At this level, too, there is a constitutive link to understanding, since we defined theoretical virtues in terms of their ability to facilitate that very epistemic achievement when the first four criteria have been satisfied.

The foregoing supports viewing the method as sound. There is more to say. For instance, the Tri-Level Method is not only friendly to the various activities in which philosophers engage when they’re doing philosophy:

- advancing arguments

- raising objections

- offering replies to these objections

- providing clarification

- developing explanations (with miscellaneous virtues)

- displaying sensitivity to the deliverances of science, mathematics, and logic.

The method also explains why it is a good thing for philosophers to engage in these activities: doing so conduces to the satisfaction of the method’s criteria (which, again, are constitutively linked to philosophy’s ultimate proper goal). Moreover, it achieves this explanation while also making sense of the attractions of familiar methods. Although their directives don’t point all the way to understanding, they’re arguably attuned to one or more of the method’s five criteria.

Yet conforming to the Tri-Level Method would not be to engage in business as usual. For one thing, it calls upon each theory to handle the full range of data: no cherry-picking! It also instructs theorists to develop their views as well and fully as they can, rather than simply to exchange arguments and objections with their rivals—as sometimes happens when theorists merely shift burdens of proof, or fixate on admissible moves within a given dialectic. Further, the method advises attention to the data while discouraging undue emphasis on parsimony and other putative theoretical virtues that should play only a tie-breaking role late in the game. The method’s criteria help keep theorists’ eyes on the prize.

The Tri-Level Method is not revolutionary. Its answer to the question of method incorporates bits of wisdom from extant methods, which enjoy popularity in one or another subfield. Its elements are also familiar from the way most philosophers ply their trade. Still, the specific instructions it contains, their rationale, and the order of operations it suggests strike us as offering a promising path to attaining theoretical understanding and, consequently, to making philosophical progress.***

notes:

* This paragraph is a very brief sketch of ideas and arguments about the structure and goals of inquiry in Chapter One of our Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (OUP, 2022), on which the whole of this post is based.

** We’ve noted some data about data. What theory best handles these metadata? Chapter Two critically discusses sociological, metaphysical, psychological, and linguistic theories of data. Chapter Three develops an alternative, epistemic theory of data, centering on the notion of a pretheoretical consideration that inquirers considered collectively have good epistemic reason to believe.

*** Chapter Six is dedicated to the matter of philosophical progress, elucidating the role of the Tri-Level Method therein.

The post Is There A Sound Philosophical Method? (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.