language

Phriscos

A “Frisco,” I recently learned, is “something that outsiders spontaneously say that secretly marks them as outsiders unbeknownst to them.”

[from a “The Far Side” comic by Gary Larson]

The concept, which came to my attention via Hanno Sauer (Utrecht), is related to the concept of a shibboleth, a linguistic term distinctive to a particular group, but kind of its opposite. Coined by Dan Engber, its name comes from the supposed fact that “people from all over the country think it’s cool to call San Francisco ‘Frisco,’ but no genuine native San Franciscans would ever use the word to describe their city.”

Several years ago we had a discussion of what we called “shibboleth names” in philosophy, that is, names the common mispronunciation of which marks speakers as inferior in some way. Maybe we should have called them “Frisco names.”

In any event, the domain of philosophical friscos—let’s just go all in and call them phriscos—goes beyond names and mispronunciations.

A classic example of a phrisco, offered by Scott Hill (Innsbruck) in response to Sauer, is using “begs the question” among philosophers to mean “raises the question” rather than “assumes the very thing it sets out to prove.” (Yes I know some of you think we should give up on this one, but nonetheless it still functions as phrisco.)

Here’s another phrisco: using “refuted” when one means “disagreed with”.

I think we could have a little fun, and at the same time provide a valuable service to philosophical novices, by identifying these phriscos.

The post Phriscos first appeared on Daily Nous.

Starmer tries to make SNP Gaza ceasefire motion all about Israel’s feelings

Labour amendments betray Gaza’s murdered and oppressed civilians and uses classic asymmetric language to value Palestinian life less than Israeli

Keir Starmer – after days of posing to try to bring Muslim and other decent voters onside by mouthing ceasefire language – has yet again betrayed the two million people in Gaza suffering violence and starvation and the more than 100,000 people murdered and maimed by Israel.

While the ‘mainstream’ media speculated whether Starmer would order MPs to support the SNP’s motion demanding a ceasefire, which is being debated in Parliament tomorrow, more realistic observers knew it was inevitable that Starmer would do the minimum he hopes will fool voters opposed to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, while protecting the interests of the pro-Israel right.

And so he did: Labour has tabled amendments to the original motion that gut it of its impact and has gone as far as making the motion more about Hamas’s supposed guilt and the feelings of Israel and its supporters. And the amendment uses the classic tactics of politicians and ‘mainstream’ media to present Israeli lives and suffering as more valuable than Palestinian.

In Starmer’s worldview, Palestinians are not being murdered by Israel – their lives are just ‘lost’, as if to a natural disaster and not to a campaign of mechanised mass murder. The sheer number of their deaths is presented as ‘intolerable’, but the loss of Israeli lives to Palestinian resistance is ‘horror’. Israelis have the ‘right to assurance’ against attack, but there is no mention of a Palestinian right not to be murdered by the occupation regime. Israel ‘cannot be expected’ to stop fighting if Hamas does not stop – but there is no acknowledgement that Hamas’s violence takes place against a backdrop of decades of wanton violence and oppression by the occupiers. Israel must be ‘safe and secure’ – but a Palestinian state only merits ‘viable’.

The SNP motion is an exemplar of directness and simplicity and rightly focuses on the many tens of thousands of civilians slaughtered by Israel, as well as on the forced displacement of 1.5 million Palestinians into Rafah, where they remain under constant bombardment and the threat of an all-out ground assault:

Labour’s lickspittle version calls resistance ‘terrorism’ but does not mention the Israeli terror state’s genocide and other war crimes, or the fact that so many are dying in Rafah because they were forced to cram there under bomb and bullet – and clearly hasn’t even been proofread, calling for ‘the UN Security Council to be meet urgently’:

Starmer is trying to mask his support for Israel’s war crimes and hoping that the millions in this country disgusted by that support will be fooled. His disregard for the true plight of Palestinians and his complicity in the war crimes being perpetrated against them by Israel is beyond contemptible.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

The Influence of Translations in Philosophy: The Case of the Tractatus

You know that famous last line of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”? That’s not quite what he said, according to Damion Searls, whose new translation of the book comes out this month. It was more like, “We mustn’t try to say what cannot be said.”

[Note: This was originally posted on February 15, 2024, 8:15am, but was lost when a problem on February 17th, 2024 required the site to be reset. I’m reposting it on February 18th with its original publication date, but I’m sorry to report that the lively, interesting, and critical discussion that took place in the comments may have been lost; I’m looking into the matter.]

And the book’s famous first line, “The world is everything that is the case”? That’s like translating “Yup, I’m sick” as “It is the case that I am sick.” A better translation would be, “The world is everything there is.”

In an essay at Words Without Borders, Searls discusses the “normalcy” of his translation, and how odd its normalcy sounds compared to the well-known translation owed to “credited translator” Charles Kay Ogden and “actual translator” Frank Ramsey.

Searls says:

Overall, the language of my new translation makes more sense than the Ogden version. Such normalcy might be off-putting to anyone who knows and loves the Tractatus in English already, but this is indeed how Wittgenstein originally sounded, even the Wittgenstein of much of the Tractatus.

The formality and weirdness of the writing of the Ogden translation, Searls argues, is in part owed to a failure to appreciate how differently German and English work:

The German reliance on nouns is why English translations of German philosophy can be so turgid: complicated nouns with bland or impersonal verbs don’t capture in English the precision and intensity of the German, they clog it up and slow it down. You don’t want to say in English that an object “has a usefulness-nature that allows it to be . . . ,” you want to say “people use it to . . . ,” with a human subject and active main verb (“people use it,” not “it has a quality”)… the temptation among academic philosophy translators is to be extra-literal about the nouns, especially in crucial moments of the German, precisely where the English most needs verbal energy.

[W]e find the Tractatus full of sentences like “The possibility of a state of affairs is contained in a proposition about that state of affairs.” This “possibility” is expressed as a noun—compare Mann’s “independence” and “self-sufficiency”—but it doesn’t belong as a noun in English: the sentence means “You can’t have a proposition without the state of affairs it describes beingpossible.” In other words, the proposition implies or presupposes that what it states is possible, even if it turns out not to be actually true. To avoid the directionality of either “implies” (a proposition yields a possibility) or “presupposes” (the possibility yields the proposition), I use the word “entails”: “A proposition entails that the state of affairs it describes is possible.”…

[T]he English translation of the Tractatus credited to C. K. Ogden and approved by Wittgenstein is inadequate. Perhaps in the grip of Wittgenstein’s model of language, Ogden (or Frank Ramsey) does indeed, as it were, replace every “Möglichkeit” with “possibility” and leave it at that. The translation very often preserves the incessant nominalization, passive syntax, and inverted word order that are fine in German but confusing and bad writing in English.

Here are some examples of that “bad writing” and Searls’ new translation:

Ogden 3.1: In the proposition the thought is expressed perceptibly through the senses.

Searls 3.1: A thought is expressed, and made perceivable by the senses, in a proposition.

Ogden 3.13: To the proposition belongs everything which belongs to the projection.

Searls 3.13: Everything that is part of the projection is part of the proposition.

Ogden 4.0641: The denying proposition determines a logical place other than does the proposition denied.

Searls 4.0641: The negating proposition defines a logical place that is different from the negated proposition’s.

Ogden 4.466: To no logical combination corresponds no combination of the objects.

Searls 4.466: There is no logical combination to which no combination of objects corresponds.

Ogden 5.3: According to the nature of truth-operations, in the same way as out of elementary propositions arise their truth-functions, from truth-functions arises a new one.

Searls 5.3: Elementary propositions produce truth-functions and truth-functions produce a new truth-function in the same way: this is the nature of truth-operations.

Searls knows that his translation will have to contend with “the prevalent idea that the English which Wittgenstein saw and approved is his—that the Ogden version is the book Wittgenstein himself wrote.” To this he responds:

The fact that Wittgenstein approved the translation of Bild as “picture” doesn’t mean that “picture” is what he was really saying: his English wasn’t good enough to make that decision. Any literary translator of living authors into a widely known language like English will have had the experience of an author who knows the translating language more or less well trying to meddle in the translation and insist on saying things a certain way, despite it often being not quite right. If the author has repeated a term, for instance, they will have had a powerful lived experience of using “the same word” each time; they are likely to underestimate the extent to which words in the other language create a kind of Venn diagram with the original word (cf. “book” and “livre”), and they will want the same English word for a usage of the original word in the nonoverlapping sliver of its circle (cf. “I have read all the books”). The translator has to insist on his or her feel for the translating language; in the end, the author isn’t writing a book in English, the translator into English is writing a book in English. For all of Wittgenstein’s stature and genius, I nonetheless include him among this perfectly ordinary class of not fully bilingual authors, whose input into the translation is not gospel and whose judgment of a translation is often plain wrong. Meanwhile, Ogden and the book’s other translators were operating in an academic framework of translation that didn’t attend to the different ways English and German work—for instance, the different amounts of dynamism in a Bild and a picture. Decades of accrued tradition, of philosophy professors and their students grappling with the English of the Ogden version and building arguments and interpretations upon it, don’t change these facts, although of course they do make it harder to accept that the existing translation is flawed.

The whole article is here.

It would be interesting to hear both what Wittgenstein scholars think of all this and of other examples of significant philosophical works whose influence is in part bound up with (supposedly) faulty translation.

The post The Influence of Translations in Philosophy: The Case of the Tractatus first appeared on Daily Nous.

Global Language Justice – review

In Global Language Justice, Lydia H. Liu and Anupama Rao bring together contributions at the intersection of language, justice and technology, exploring topics including ecolinguistics, colonial legacies and the threat digitisation poses to marginalised languages. Featuring multilingual poetry and theoretically rich essays, the collection provides fresh humanities perspectives on the value of preserving linguistic diversity, writes Andrew Shorten.

Global Language Justice. Lydia H. Liu and Anupama Rao (Eds.)with Charlotte A. Silverman. Columbia University Press. 2023.

Recently, scholars have been paying closer attention to the relationships between language and justice, leading to two separate but related strands of academic research. On one side, applied linguists are increasingly preoccupied with issues connected to social justice, race and gender. An example of this is Ingrid Pillar’s influential book Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice (Oxford, 2016), which explores how language hierarchies, ideologies and expectations affect people’s access to meaningful work and social participation. On the other side, political theorists are incorporating language into discussions about democracy and distributive justice, exploring how political communities should handle multilingualism and questioning whether people have justice-related claims or duties tied to the languages they use. A well-known example of this is Philippe Van Parijs’s book Linguistic Justice for Europe and the World (Oxford, 2011), which provocatively argues that native English speakers have a duty to compensate non-native English speakers since the latter group’s efforts contribute to a tremendously beneficial public good.

Recently, scholars have been paying closer attention to the relationships between language and justice, leading to two separate but related strands of academic research. On one side, applied linguists are increasingly preoccupied with issues connected to social justice, race and gender. An example of this is Ingrid Pillar’s influential book Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice (Oxford, 2016), which explores how language hierarchies, ideologies and expectations affect people’s access to meaningful work and social participation. On the other side, political theorists are incorporating language into discussions about democracy and distributive justice, exploring how political communities should handle multilingualism and questioning whether people have justice-related claims or duties tied to the languages they use. A well-known example of this is Philippe Van Parijs’s book Linguistic Justice for Europe and the World (Oxford, 2011), which provocatively argues that native English speakers have a duty to compensate non-native English speakers since the latter group’s efforts contribute to a tremendously beneficial public good.

Political theorists are incorporating language into discussions about democracy and distributive justice, exploring how political communities should handle multilingualism

Bringing together linguists with scholars from across the humanities, Global Language Justice throws new light on these and other, related, topics. Emphasising the relationships between language, environment and technology, and featuring both poetry and academic essays, this edited collection brings a fresh perspective on the emerging “ecolinguistics” research agenda, which explores the entanglements amongst struggles to protect biological, linguistic and cultural diversity. The book succeeds in bringing new issues to the fore, especially regarding the challenges of digitisation for language justice and the connections between coloniality and language justice. Another laudable feature of this book is that, far more than is typical for an edited collection of this type, it has the feel of a genuinely collaborative project, with frequent cross-referencing across the different chapters, most of which were first presented at a Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar, hosted by Columbia University.

The book succeeds in bringing new issues to the fore, especially regarding the challenges of digitisation for language justice and the connections between coloniality and language justice.

Many of the chapters centre the predicament of Indigenous languages and the experiences of Indigenous language activists. This marks a contrast with both strands of research mentioned earlier, which tend to focus on the claims of sub-state national minorities and, to a lesser extent, immigrants. Careful engagement with Indigenous scholars, activists and communities should prompt a reconsideration of some dominant linguistic and political categories. For instance, Wesley Leonard’s insightful contribution demonstrates how creative attempts to revitalise the once dormant myaamia language, led by Miami people themselves, destabilise assumptions about linguistic purism, language extinction, and the connection between language and identity. Furthermore, situating issues of language justice within a broader context of Indigenous politics and experiences can foreground phenomena often neglected by linguists and language rights scholars. For instance, Daniel Kaufman and Ross Perlin’s chapter reveals how bureaucratic and academic practices can render Indigenous languages invisible in urban metropolises like New York. They argue that this erasure can have material as well as recognitional costs, threatening the health and human rights of Indigenous people.

Whilst the importance of literacy for personal wellbeing, economic growth and gender equality are now well understood, the importance of mother-tongue education for developing literacy in the first place is less widely appreciated.

A second theme that emerges is the importance of language for sustainable development. Suzanne Romaine’s powerful chapter points out that although the most linguistically diverse places are inhabited by some of the world’s poorest people, development policies and practices generally neglect language. For instance, whilst the importance of literacy for personal wellbeing, economic growth and gender equality are now well understood, the importance of mother-tongue education for developing literacy in the first place is less widely appreciated. As a result, schools, states and international agencies still often prioritise the teaching of official and colonial languages, which results in low literacy rates and can have devastating effects for both individuals and society. Particularly striking are the facts that, globally, 40 per cent of people lack access to education in their own language, a proportion that rises to 87 per cent in Africa, where 90 per cent of people also cannot understand the official language(s) of their state.

Some lesser-used languages are virtually impossible to use online because their writing systems are not supported in Unicode, the international standard that ensures text can be reliably transmitted across devices and programmes.

A third theme explored relates to the presence and visibility of minoritised languages online. Isabelle A. Zaugg’s chapter discusses some of the ways in which digital technologies discourage the use of lesser-used languages online and thereby reinforce sociolinguistic inequalities. Part of the explanation for this is that only languages spoken in wealthy countries enjoy a full suite of digital supports, such as tailor-made fonts and keyboards, as well as tools like spellcheck, predictive typing and voice recognition. By contrast, as Deborah Anderson explains in her clear and useful chapter, some lesser-used languages are virtually impossible to use online because their writing systems are not supported in Unicode, the international standard that ensures text can be reliably transmitted across devices and programmes. In the future, encoding the scripts used by minority languages will become ever more essential for language maintenance and vitality, since Unicode underpins a myriad of important practices, from word processing and searching the internet to emailing and posting on social media. However, this process is both technically challenging and resource hungry, raising questions of justice for minority language speakers.

Though it is surely true that language justice requires thinking carefully about other political concepts […] we should be reluctant about abandoning rights-talk altogether.

Finally, a fourth theme of the book is a broad scepticism about language rights, primarily because of the ways in which rights are thought to be bound up with liberal individualism. This is suggested in a few contributions and defended most fulsomely in the chapter by L. Maria Bo. Though rights scepticism has a respectable tradition in political theory, this was one of the less convincing aspects of the collection, not least because the linguistic human rights approach, championed elsewhere by Robert Phillipson and the late Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, was never given a serious run for its money. Though it is surely true that language justice requires thinking carefully about other political concepts (such as democracy, as Madeline Dobie argues in her enlightening chapter on language politics in Algeria), we should be reluctant about abandoning rights-talk altogether. For one thing it is often favoured by language activists themselves, such as Gluaiseacht Cearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta (The Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement) active in Ireland in the 1960s and 70s. Furthermore, as Tommaso Manfredini demonstrates in his moving contribution about shortcomings in translation services for asylum seekers in Italy, rights and especially human rights cannot be ignored, since they provide the context and means with which language injustices can be most effectively challenged today.

Liu and Rao’s Global Language Justice is a stimulating addition to the burgeoning academic field of linguistic justice. It offers a fresh perspective from the humanities that will be especially welcome for scholars already immersed in the literatures in applied linguistics or normative political theory. Meanwhile, other readers will find much in its theoretically rich reflections on the predicament of minority languages, and their users, in the twenty-first century.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Alexandre Laprise on Shutterstock.

Language and the Rise of the Algorithm – review

In Language and the Rise of the Algorithm, Jeffrey Binder weaves together the past five centuries of mathematics, computer science and linguistic thought to examine the development of algorithmic thinking. According to Juan M. del Nido, Binder’s nuanced interdisciplinary work illuminates attempts to maintain and bridge the boundary between technical knowledge and everyday language.

Language and the Rise of the Algorithm. Jeffrey Binder. The University of Chicago Press. 2023

Arguably, the history of what we now call algorithmic thinking is also the history of the consolidation of algebra, mathematics, calculus and formal logic as tools for composing, enunciating, and thinking about abstractions such as “some flowers are red”. But in less obvious ways, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm shows, it is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world. In other words, it is the history of ensuring that “red” actually means red – that we are all clear on who sets what red means (for example, experts through definition or ordinary people through usage) and agree on it – and of whether agreeing about these things is what matters when we use language.

Arguably, the history of what we now call algorithmic thinking is also the history of the consolidation of algebra, mathematics, calculus and formal logic as tools for composing, enunciating, and thinking about abstractions such as “some flowers are red”. But in less obvious ways, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm shows, it is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world. In other words, it is the history of ensuring that “red” actually means red – that we are all clear on who sets what red means (for example, experts through definition or ordinary people through usage) and agree on it – and of whether agreeing about these things is what matters when we use language.

The history of what we now call algorithmic thinking […]is also the history of trying to compute with, and often in spite of, language, to convey a meaningful proposition about the world.

Harking back to the 1500s, the first of the book’s five chapters examines attempts to use symbols to free writing from words at a time when vernaculars where plentiful, grammars unstable and literacy rates low. Algebra was not then considered part of mathematics proper but its rules, expressed in spoken language, were used for practical purposes like calculating taxes and inheritance. From myriad writing experiments emerged algebraic symbols: uncertain and indeterminate, they enabled computational reasoning about unknown values, a revolution that peaked when Viète first used letters in equations in 1591 (33-36).

Algebra was not [In the 1500s] considered part of mathematics proper but its rules, expressed in spoken language, were used for practical purposes like calculating taxes and inheritance

Chapter Two explores Leibniz’s attempts to produce a philosophical language made of symbols and unburdened by words, such that morals, metaphysics, and experiences are all subject to calculation. This was not an exercise in spitting out numbers, but with the aim of demonstrating the reasoning behind every step of communication: a truth-producing machine (62-64). The messiness of communication struck back: how can one ensure that all terms and their nuances are understood in the same way by different people? Leibniz argued that knowledge was divinely installed in us, waiting to be unlocked by devices such as his, but Locke’s argument that knowledge comes from sensory experience and requires an agreement over what things mean won the day (79), paving the way towards an emphasis on concepts and form.

Leibniz argued that knowledge was divinely installed in us, waiting to be unlocked […] but Locke’s argument that knowledge comes from sensory experience and requires an agreement over what things mean won the day

Leibniz also sought to resolve political differences through that language. Chapter Three argues Condorcet shared this goal and the premise that vernaculars were a hindrance, but contrary to Leibniz, he believed universal ideas needed to be taught, not uncovered. Condillac’s and Stanhope’s experiments with other logical machines – actual, material devices designed to think in logical terms through objects – epitomised two tensions framing the century after the French Revolution: first, the matter of whether the people, and their vernacular culture, or the learned, and their enlightened culture, should govern shared meanings – that is to say, give meaning – and second, whether algebra should focus on philosophical and conceptual explanations or on formal definitions and rules (121).

The latter drive would prevail, and as Chapter Four shows, rigour came to emanate not from verbal definitions or clarity of meanings, but from axiomatic systems judged on consistency: meanings are irrelevant to the formal rules by which the system operates (148). Developing this consistency would not require the complete replacement of vernaculars Leibniz and Condorcet argued for: rather, symbolic forms would work alongside vernaculars to produce truth values, as with Boolean logic – the one powering search engines, for example. The fifth and last chapter, “Mass Produced Software Components”, rise of programming languages, in particular ALGOL, and the consolidation of regardless of specifics: intelligible, actionable results within a given amount of time (166).

Binder’s rigorous dissection of debates over language, philosophy, geometry, algebra, history and culture spanning 500 years integrates debates that most disciplines today, aside from some strands of media studies and Science and Technology Studies, tend to treat separately

This book is a tightly packed, erudite contribution to the growing concern in the Humanities with algorithms. Binder’s rigorous dissection of debates over language, philosophy, geometry, algebra, history and culture spanning 500 years integrates debates that most disciplines today, aside from some strands of media studies and Science and Technology Studies, tend to treat separately or with a poor sense of their inbuilt connections. A welcome result of this exercise is the historicisation of certain critiques of technological interventions in politics that, generally lacking this kind of integrated, long-range view, we tend to treat as novel and cutting-edge. For example, an 1818 obituary for Charles Mahon, third Earl of Stanhope and inventor of the Demonstrator, a “reasoning machine”, already claimed that technical solutions for other-than-technical problems such as his tend to replicate the biases of their creators (113), and often the very problems they intended to solve. This critique of technoidealism is now commonplace in the social sciences.

A second benefit of the author’s mode of writing is not explicit in the book but is arguably more consequential. From Bacon’s dismissal of words as “idols of the market” in 1623 (15) to PageRank algorithm’s developers’ goal to remove human judgement by mechanisation in the 1990s (200), the book traces attempts across the centuries to free reason and knowledge from language and rhetoric. In doing this, Language and the Rise of the Algorithm effectively serves as a highly persuasive history of the affects, ethics and aspirations of technocratic reason and rule. The book cuts across the histories of bureaucracy and expertise and the birth of governmentality to tell us how an abstraction in how we make meaning work emerged – an abstraction we are asked to trust in, and argue for, partly because it is the kind of abstraction it ended up being.

The book traces attempts across the centuries to free reason and knowledge from language and rhetoric

This is a rich and nuanced book, at times encyclopaedic in scope, and except for a slight jump in complexity and some jargon in the fifth and last chapter, it will be accessible to readers lacking prior knowledge of algorithms, mathematics or language philosophy. It will be of interest to scholars across the social sciences and humanities, from philosophy and history to sociology and anthropology, as well as readers in political science, government studies and economics for the reasons listed above. It could work as course material for very advanced students.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Lettuce. on Flickr.

Cartoon: Climate newspeak at COP28

"Polarization" has become a weasel word for bad actors to stop legitimate criticism. The fact that we're seeing it used by an oil CEO to deny climate science should set off alarm bells.

Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, the president of COP28 who also happens to be CEO of the UAE's state oil company, made this and other disturbing remarks while speaking with three women at a She Changes Climate event.

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

Hallucinating AIs and What The Words Of The Year Lists Reveal About our Modern World

Newsletter offer

Newsletter offer

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive editorial emails from the Byline Times Team.

If, as Samuel Johnson once wrote, “language is the dress of thought”, dictionaries around the world are encasing themselves in stainless steel and advancing towards us with an ominous clank: Artificial Intelligence (AI) – and all that this technology might one day entail – is all over 2023’s ‘Word of the Year’ lists.

In fact, AI-related words appear in the shortlists of pretty much all the dictionaries that have so far published their Word of the Year (WOTY) nominations. ‘AI’ is the winner for Collins and ‘Generative AI’ came out top in the Australian Macquarie Dictionary’s 'people’s choice', while other dictionaries such as Oxford, Cambridge, and Merriam-Webster all flag up AI-related words. What’s interesting about some of these nominations is not that AI appears – technology is (and has always been) one of the leading drivers of linguistic innovation – but the lens through which it has been viewed.

Take the Cambridge Dictionary’s decision to make ‘hallucinate’ its word of the year. That’s not a new word, you might say, and you’d be right. Well, this is ‘hallucinate’ with a very specific meaning: it’s when an AI produces false information, so responding to a ‘prompt’ (a word which is on the Oxford WOTY 2023 shortlist) such as ‘write a product description for this phone’ with a set of factually incorrect statements.

That is one of the common pitfalls of Generative AI at the moment: there is an almost infinite amount of data out there for it to train on, but can it decide what’s fact or fiction? Using ‘hallucinate’– a verb that usually has a human as its subject – seems to be ascribing almost human qualities to AIs.

That’s something that the lexicographers at the Cambridge Dictionary point out themselves in their analysis of corpus data: we are now starting to see the verb being applied to AIs as well as humans and also a shift in use from the term ‘AI’ meaning ‘the study of artificial intelligence’ to AI as a countable noun: an AI, many AIs, a world on the cusp of a dystopian future at the hands of all-powerful AIs? Is this android really dreaming of electric sheep?

The Upside Down: Saint Cuthbert – Wonder Worker

John Mitchinson reflects on why the life of Saint Cuthbert still has important things to teach us

John Mitchinson

The human lens also comes into play with the leading US dictionary, Merriam-Webster’s 2023 WOTY choice of ‘authentic’, which it admits is ‘hard to define and subject to debate’ at the best of times, tending to lead people to look it up, thus alerting the dictionary-makers to a spike in interest. How can we be our ‘authentic’ selves? What does ‘authentic’ even mean in a world where many people in the public eye – especially on social media where ‘authenticity’ is a whole look – are performing different versions of themselves all the time?

But it is the broader influence of technology and AI again that shows how appropriate ‘authentic’ is in these not-so-best-of-times, where people are increasingly asking what’s real and what’s fake online (‘deepfake’ is also on the Merriam-Webster 2023 shortlist), and it comes after its 2022 winner ‘gaslighting’, another word that reflects current fears of being misled and duped by what we see with our very eyes. There’s clearly something in the water.

The dictionaries themselves are quite transparent about how they have reached some of their decisions. Far from being the gatekeepers of vocabulary that many purists and pedants want them to be, the dictionaries source their words from actual usage. They are genuinely responding to what is being looked up and what people are saying and writing, whether that is Macquarie’s experts deciding that their WOTY choice is ‘cozzie livs’ (the distinctly Australian-sounding, but actually very British abbreviation for ‘cost of living crisis’) or Merriam-Webster noting the increased interest in the US for King Charles’s ‘coronation’ (but sadly not the ‘corrie nash’ or ‘chazzle dazzle’). And they are using technology to track these changes.

In fact, dictionaries are making use of the same kind of corpus data (massive databases of language) that Large Language Models like Chat GPT train on. But as the Cambridge Dictionary is quick to point out – never knowingly letting a WOTY announcement not be a marketing opportunity for its own dictionary brand – it still employs humans to check the output and make the final decisions with all its publications.

Don't miss a story

Meanwhile, Oxford has opted to decide its WOTY by a completely foolproof public vote from its shortlist of eight words. And when has a popular vote ever gone wrong? (Aside from last year's Oxford WOTY 'Goblin mode'; the Boaty McBoatFace debacle, and 2016, when the voting public actually voted for both Brexit and Donald Trump?) What could possibly go amiss when superfans of ‘rizz’ for ‘charisma’ might produce ‘deepfakes’ of Taylor Swift to prevent ‘Swiftie’ taking its inevitable WOTY 2023 crown?

The great dictionary maker, Samuel Johnson, probably wouldn’t have been impressed with this populist approach but then while he had a lot of interesting things to say about language, and some famously eccentric definitions in his landmark dictionary, he was never a great fan of popular opinion leading the way. And maybe ‘goblin mode’ tells us he was onto something.

The Rise of English as the Global Lingua Franca of Academic Philosophy (guest post)

“We think it is more or less inevitable at this point that English will be the global lingua franca of academic philosophy for the foreseeable future. We also think it is for the most part a good thing. But it has also produced some problems…”

In the following guest post, Peter Finocchiaro (Wuhan) and Timothy Perrine (Rutgers) argue that “the rise of English as the global lingua franca of academic philosophy might lead to several epistemic goods being unjustly distributed in our community, including credibility, education, and the standing to speak.”

The Rise of English as the Global Lingua Franca of Academic Philosophy

by Peter Finocchiaro and Timothy Perrine

Academic philosophy is a global institution. Nearly every country has universities with philosophy departments. Philosophy journals are read around the world. And many philosophers grow up in one country, get a PhD in another, work in a third, and have students who come from a fourth. Like many global institutions, academic philosophy has increasingly relied on English as a shared language for communication—as a global “lingua franca”. When a Finnish philosopher meets a Colombian philosophy at a conference in Japan, they will likely do philosophy in English.

We think it is more or less inevitable at this point that English will be the global lingua franca of academic philosophy for the foreseeable future. We also think it is for the most part a good thing. But it has also produced some problems for our community—problems that we think need to be analyzed and addressed so that philosophy can be more inclusive.

To get a sense of the kinds of problems we have in mind, consider the following case. A philosopher is fluent in English, having learned it as a second language. Their academic research consists in reading and writing in English. But a recent referee report complains that their paper is “not idiomatic” (even though the referee doesn’t identify a single passage that is unclear, disorganized, or obscure) and requests that the philosopher have their paper checked by a “native” speaker of English. So, to appease the referee, the philosopher reaches out to a “native” English speaking colleague. Both philosophers then spend some time trying to guess what’s not “idiomatic” so that the language can be “fixed” and the paper can be published.

Maybe this sort of thing hasn’t happened to you. But it’s almost certainly happened to someone you know or someone that you’ve read. It has happened several times to our coworkers and friends.

In a new paper of ours, we argue that these problems are instances of language-related injustice. The paper is part of a new special issue of Philosophical Psychology on understanding bias. Thanks to the generous support of Lex Academic, it is freely accessible here for 12 months as the winner of the Lex Academic® Essay Prize for Understanding Linguistic Discrimination.

As we argue in the paper, in the above case the philosopher gets labelled as a “non-native” speaker of English and is held to certain linguistic norms set by a “native” English speaking community. But satisfying those norms is unnecessary for understanding their paper. We analyze this and other cases using the framework of epistemic injustice, specifically distributive epistemic injustice (though we think there can be other frameworks that are also useful). We argue that the rise of English as the global lingua franca of academic philosophy might lead to several epistemic goods being unjustly distributed in our community, including credibility, education, and the standing to speak.

At the end of our paper, we consider some proposals for dealing with these. They are:

1A: Increase assistance with English—journals should provide English-language services such as proofreading at no cost to the author.

1B: Abandon “readability” standards—journals should stop evaluating submissions on the basis of “readability”, including how “idiomatic” the English is as well as its “flair” or “style”.

2A: Diversify the canon—philosophers (and journals) should engage with work from a wide range of traditions, not just the mainstream Western canon.

2B: Expand the SEP—articles written for the SEP should be translated into other languages and/or the SEP should commission original entries in other languages.

3A: Increase non-native English speaker representation—editorial boards of journals, admissions committees of graduate programs, etc., should include more non-native speaking philosophers.

3B: Increase cross-linguistic representation—journals should publish material that spotlights non-English language philosophy, especially that which is produced in non-Anglophone countries.

Readers may recognize some of these proposals. In 2021, Filippo Contesi created the Barcelona Principles for a Globally Inclusive Philosophy, which was discussed on Daily Nous here, with related discussion here. Contesi’s Principle 3 is almost identical to our Proposal 3A, and Principle 1 is very similar to our Proposal 1B.

In our paper, we briefly argue that the B proposals are better than the A proposals. As we see it, Proposal 1A is likely to just reinforce unnecessary linguistic norms that privilege native speakers; a better alternative, as expressed by Proposal 1B, is to abandon the enforcement of those linguistic norms. Proposal 2A is admirable and in general we favor diversifying the cannon. But we doubt it would do much to address the linguistic injustices we are worried about. A better alternative, as expressed by Proposal 2B, is to make current high-quality research more accessible to people from different linguistic backgrounds. Proposal 3A is similarly admirable, but non-native speakers are likely already overburdened with administrative tasks. A better alternative, as expressed by Proposal 3B, is to increase the representation of current research from philosophical communities working in languages other than English.

Maybe our evaluation of these proposals isn’t exactly right. We’re open to being corrected about that since an adequate evaluation should rely on a complex balance of empirical facts, personal experiences, and communal structures that we can’t claim to be experts in. We’re more interested in bringing greater attention to the conversation that Contesi and others have started: what should be done about the problems caused by English becoming the global lingua franca of academic philosophy? Indeed, since the both of us are “native” speakers of English, we’re eager to hear more from others, especially “non-native” speakers.

So let us know what you think of these proposals, and let us know what you think about other proposals that we haven’t mentioned. Additionally, we’d be interested in hearing about people’s experiences that don’t neatly fit into the cases we give above or in the full paper. At the end of the day, what we want is for academic philosophy to be more inclusive for all of its members around the globe.

The post The Rise of English as the Global Lingua Franca of Academic Philosophy (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

Cartoon: This week in authoritarian newspeak

George Orwell's 1984 gets invoked a lot these days, but what happened to the word "woke" is exactly what was intended with Newspeak. Per Wikipedia, "Orwell explains that Newspeak follows most rules of English grammar, yet is a language characterised by a continually diminishing vocabulary; complete thoughts are reduced to simple terms of simplistic meaning." With "woke" we see the entire project of humanism reduced to a stupid insult. Shamefully, many political commentators not on the authoritarian right still use this lazy shorthand to belittle activists or anything vaguely socially conscious, invoking the right's pejorative framing.

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

AI Is Helping Indigenous Teens in Brazil Keep Their Mother Tongue Alive

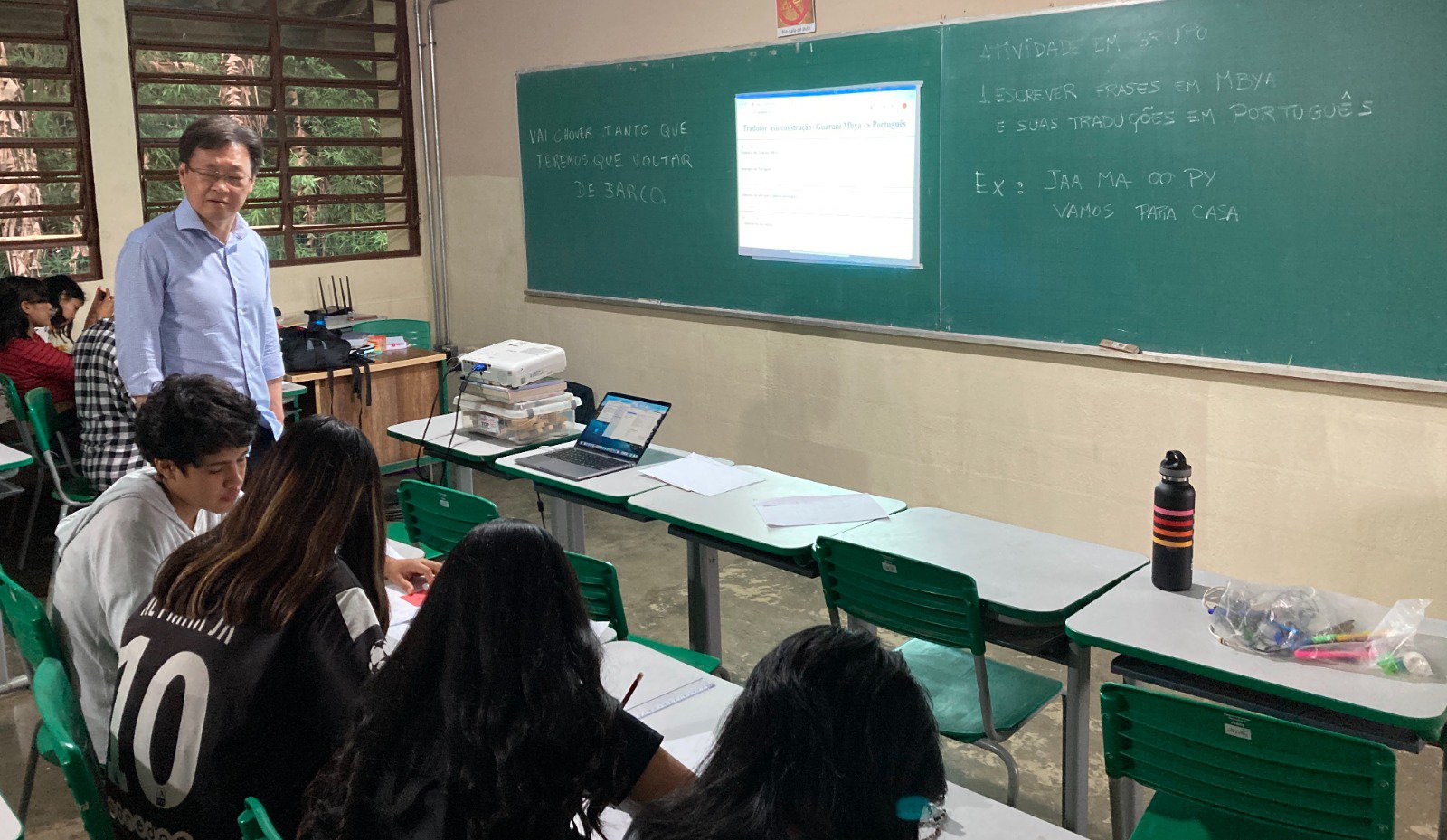

Huddled in small groups around laptops, 20 Brazilian teenagers — a group including TikTok influencers and gamers — are using an app to build a skill that’s vital to the future of their entire community.

The teenagers belong to the Guarani Indigenous people, based in a community two hours from São Paulo, and they are fluent in speaking both Portuguese and their mother tongue, Guarani Mbya. But when it comes to writing, they often default to Portuguese as that’s what they were first taught to write in, putting the Guarani Mbya language in its written form at risk of disappearing.

But since March of this year, they’ve been using an app to improve their ability to write in Guarani Mbya. The “Linguistic Assistant” app works like the autocorrect and text suggestion feature on cell phones to help them build on the sentences they start writing themselves.

Guarani students are learning how to write in their native language from the app. Courtesy of IBM

Guarani students are learning how to write in their native language from the app. Courtesy of IBM

The app is part of a project funded by IBM to create AI tools to help preserve and expand the use of Indigenous languages in Brazil. The students — who make up the sole high school class across seven villages of around 3,000 people, on a reservation of 23,000 square miles — were nominated by their wider community to be the focus of IBM’s AI for Indigenous languages social impact work in their region.

The results so far are promising, according to Dr. Claudio Pinhanez, an AI specialist at IBM and visiting professor at the University of São Paulo (USP), who is leading the project. “By the end of the semester, we saw they were starting to write longer sentences on their own in their language. The progress they were making is amazing,” he says.

Digital empowerment for vulnerable languages

Guarani Mbya is one of 202 Indigenous languages spoken in Brazil, with 190 of them considered at risk of dying out — and 22 already have. With around 17,000 speakers, Guarani Mbya is classified by UNESCO as a vulnerable language, meaning that while it’s widely spoken, its use is restricted to certain domains, for example, like the home, or with certain family members.

Of the 7,000 or so languages that exist in the world, about a fifth are thought to be endangered, with the United Nations estimating that half of these will be extinct or close to it by 2100 — the majority being Indigenous languages. Hence it’s declared 2022 to 2032 the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, to help increase resources, support and awareness for their protection, recognizing in particular the role technology has to play in what it calls “digital empowerment.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

The movement to prevent Indigenous languages from disappearing has prompted a number of tech-centric language preservation and expansion projects like the one Dr. Pinhanez is leading at IBM and USP. For example, in Australia, where First Nations people speak more than 250 Indigenous languages, the University of Melbourne has launched its 50 Words project, an interactive language map that aims to offer at least 50 words of each Australian Indigenous language, as part of a nationwide Indigenous language preservation movement.

In neighboring New Zealand, nonprofit media organization Te Hiku has developed an app to collect oral recordings of Indigenous languages across the region, to help speakers boost their everyday use of their native language. And recognizing, as the Guarani people have, that the written form of a language can be challenging and equally important to preserve, a type foundry worked closely with Indigenous communities in Canada to develop new typefaces that make it easier for them to express themselves in writing.

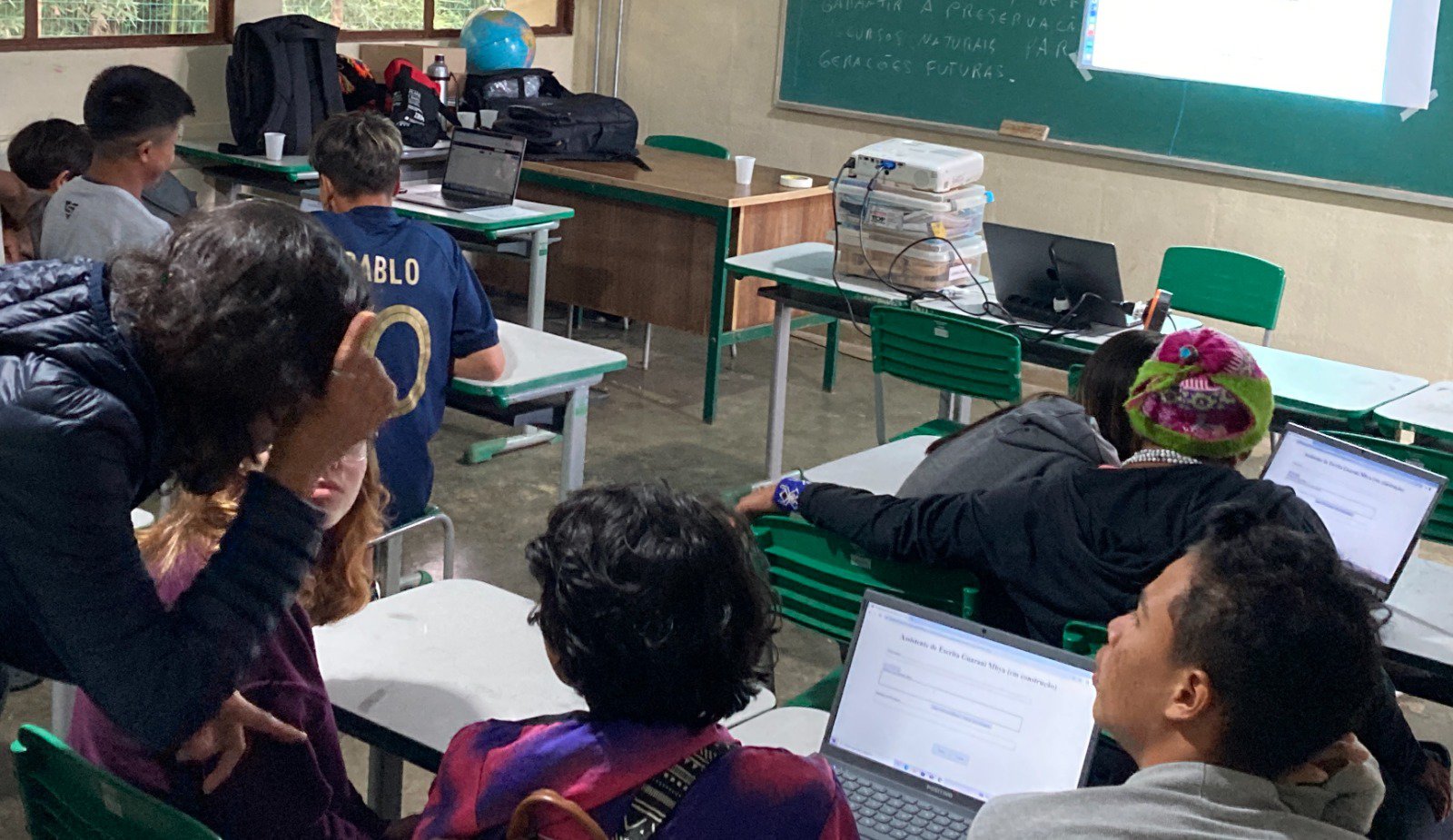

Buoyed by how the Guarani teens have embraced technology to improve their written native language skills, Dr. Pinhanez and his team now plan to evolve the chatbot from a desktop app to one that can be downloaded to a cell phone, which will look and feel like WhatsApp.

After one semester, students were starting to write longer sentences on their own in their language. Courtesy of IBM

After one semester, students were starting to write longer sentences on their own in their language. Courtesy of IBM

“[The teens] see writing as a way to integrate their many communities, and to be able to tell their own stories in a way that is more stable than just speech. The community told us their youth were very interested in computers and engaged in social media, but needed to improve their native language writing, and that’s where they want us to help,” says Dr. Pinhanez.

He and his team are also keen to offer the tool as a free resource to other Indigenous communities, emphasizing that this is a strictly nonprofit initiative.

Embracing technology while protecting culture

With projects like these, there are two key considerations that are inherently linked: the importance of co-developing and co-designing AI tools and frameworks with Indigenous communities, and the need to train Indigenous people in coding and development. Doing so gives them real stewardship of such projects, as Dr. Pinhanez outlined in a recent paper he co-authored.

But embracing technology and the desire to protect culture and language are often at odds in Indigenous communities, as Dr. Drea Burbank has observed. Dr. Burbank grew up on Nez Perce lands in Idaho, is trained in Indigenous health and had a nine-year career as a firefighter working closely with Indigenous communities in the US and Canada.

She is now the founder and CEO of Savimbo, an organization which helps Indigenous small farmers and Indigenous communities in the Amazon sell carbon and biodiversity credits. Savimbo also supports them with land rights, literacy and bank accounts. Dr. Burbank has been based near the town of Villagarzon in Colombia since May 2022.

“A minority group that’s fighting to preserve a counterculture will create walls around the culture to try not to dilute it, because the majority culture is automatically going to wipe that culture out,” says Dr. Burbank.

While many of the Indigenous communities Dr. Burbank works with feel technology could contribute to that dilution, she believes it can benefit Indigenous communities. For example, she is looking specifically for partners to help create banking interfaces in Indigenous languages, powered by voice recognition passwords. She’s concerned, though, that a lack of tech savviness would hamper these communities’ ability to properly consent to and govern the use of AI language tools.

The teens “see writing as a way to integrate their many communities, and to be able to tell their own stories in a way that is more stable than just speech,” according to Dr. Pinhanez. Courtesy of IBM

The teens “see writing as a way to integrate their many communities, and to be able to tell their own stories in a way that is more stable than just speech,” according to Dr. Pinhanez. Courtesy of IBM

“We’re talking about communities where even turning on an iPhone or writing a password is a barrier. It’s very difficult for them to give informed consent for novel technologies,” says Dr. Burbank.

That’s why José Alberto Garreta Jansasoy, Governor of the Cofán Indigenous Reservation in Colombia and a Savimbo advisor, would like technology to come with wider strategies to support the communities more holistically. He believes videos could be a helpful resource for teaching the Cofán language to young people, as it’s currently not widely spoken. He would also like to see resources allocated to Cofán language-specific schools.

“Spanish is more commonly practiced for better communication with outsiders, which has led to the unfortunate consequence of gradually abandoning our native language. Fortunately, we have realized this and are working to reclaim our language,” says Jansasoy.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Fellow Savimbo advisor Ramón Uboñe Gaba Caiga, a community leader in the Waorani tribe in Ecuador, feels optimistic that AI tools for preserving Indigenous languages can have the double benefit of expanding environmental and sustainability knowledge, as so much of that is tied into the language.

“It is very important today that young people can have a digital file where they can know the reality of us, and how we protect biodiversity, territory education and health, to have this information as a database for future generations,” says Gaba Caiga, who speaks Wao Terero, which is only spoken by about 5,000 people.

Reciprocal benefits to AI

Indigenous languages can also help to develop AI further, as Dr. Pinhanez points out. Large language models like ChatGPT have not necessarily been trained ethically, having been fed novels and texts without permission from the authors. Since Indigenous communities would need to actively provide texts and consent to their use, working with them could help to change the status quo when it comes to AI practices. And as Indigenous societies’ belief and reasoning systems differ dramatically from Western cultures, using more of them as stimulus for AI models would help remove some of the limits they currently face when it comes to how reasonable and wide-ranging their responses are.

As Dr. Pinhanez writes: “Documentation and vitalization of Indigenous languages has this unique quality of pushing AI to be better in terms of technology and ethics at the same time.”

The post AI Is Helping Indigenous Teens in Brazil Keep Their Mother Tongue Alive appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.