philosophy

Until Death It is All About Life

Life is a hero’s journey, not a drama triangle.

Our lives are filled with ups and downs. Challenges arise, conflicts emerge with others, and sometimes we fall into victimhood stories. It’s easy to get trapped in what’s called the “drama triangle” – bouncing between the roles of victim, villain, and hero in an endless cycle.

But we can break this pattern. Rather than reacting to life’s dramas, we can take charge of our own heroic journey.

The drama triangle often plays out like this: something bad happens, and we feel like victims. We blame others or the world for our misfortune. We might even lash out and make someone else the villain. Eventually, we try to “heroically” resolve the conflict and gain redemption.

But the resolution is temporary. Before long, the drama cycle begins again as we struggle against new villains and obstacles. We never escape the triangular dynamic of fighting monsters we perceive outside ourselves.

Life doesn’t have to be this endless reactionary loop. What if we stepped back and saw life as our hero’s journey, not someone else’s drama?

Heroes in myths and movies like Luke Skywalker or Harry Potter follow a different path. They get called to adventure, cross thresholds, face trials, clash with enemies, receive mentoring, and emerge transformed. The journey is inward, not just outward.

We are the heroes of our lives. Will we accept the call to adventure? Our trials may come from within as much as from external forces. Blaming situations just traps us in the drama triangle. But taking responsibility puts us on the hero’s path.

Mentors can help, like Dumbledore guiding Harry. But ultimately, we must mentor ourselves, finding inner wisdom when we feel most lost. As heroes, we keep moving forward. Our transformation comes when we stop fighting villains and instead understand how all of life initiates us.

We will falter at times. The drama triangle lurks, tempting us with victimhood and righteousness. But we can step back and remember that life is our adventure tale. Every chapter prepares us for rebirth.

Until our death, our choice on this earth is to live as heroes. The journey may be hard, but embracing it is the only way we can become who we’re meant to be. Our life is what we make of it.

If you’d like to stay on top of areas like this, you should be reading my weekly newsletter. You can follow here or on Substack.

Photo by Chris Yang on Unsplash

The post Until Death It is All About Life first appeared on Dr. Ian O'Byrne.

The Empathy Gap and a Politics of Extremes

Newsletter offer

Newsletter offer

Receive our Behind the Headlines email and we'll post a free copy of Byline Times

Whatever you think of politicians, they have a crucial, albeit often understated, role in British life: they frame the ideas of who and what we are to care about. Such framing, aligned with (and often in step with) the editorial obsessions of the dominant media, creates what might be called the ‘majority moral conscience’ of a nation.

The role of religion has been, to a large extent, handed over to such politicians, who act as a sort of litmus test for our notions of good and evil, right and wrong.

The right-wing political classes, spurred on by an inevitable headline in the Daily Mail, tell us that migrants are a source of concern. That bully dogs are too. That addressing vaping, or drugs, or 'lefty lawyers' will address society’s failures. Such critique is, of course, never about their own shortcomings – always the fault of the other.

Many see through this. This month, research by King's College London and Ipsos UK found that almost two-thirds of Brits believe our politicians use ‘culture wars’ to distract from other issues, with 62% of those polled claiming that politicians "invent or exaggerate" culture wars as a political ploy. This is up from 44% some three years ago.

In recent weeks, this enforced framing of what is good and what is not good has been tested to its limits.

Hypocrisy and Tribalism: The Dangers of Our ‘So What?’ Political Culture

Renowned weapons expert Dan Kaszeta, who was blacklisted by the Government over his tweets, explores how ‘amoral familism’ has come to penetrate our public life

Dan Kaszeta

The violence unfolding in Israel and Gaza has led to a polarisation and woe betide politicians who seek nuance. Conservative MP Paul Bristow was sacked from his Government post after calling for a Gaza ceasefire; Labour MP Andy McDonald had the whip suspended after saying the controversial phrase 'between the river and the sea' at a pro-Palestinian rally. As if you are unable to believe that the massacre of Israeli citizens by Hamas and the subsequent murderous bombardment of Gaza are both terrible events.

Such a lack of consideration was there when Suella Braverman accused hundreds of thousands of people marching over Gaza of acts of hate. It was there in the Government’s attempts to criminalise, detain and deport asylum seekers. And it is there in its condemnation of international human rights treaties.

At the root of this dualistic framing – the distillation of complex issues to the singular poles of friend or foe – lies an erosion of the most complex of political emotions: empathy.

This has revealed itself in the COVID Inquiry, where it has emerged that Downing Street colleagues called each other ‘morons’ and ‘c****’, or in Boris Johnson allegedly thinking that old people should accept their fate in the pandemic.

In the end, it is a deficit that impacts us all.

Last year, former Conservative peer Patience Wheatcroft observed in the Guardian that “you don’t have to be a socialist to find UK levels of poverty intolerable – but Liz Truss lacks the empathy to see it”. As Wheatcroft noted, Truss “misread the public mood as well as the markets.” The consequences of her empathy deficit are, arguably, still being felt today as the Bank of England maintains rates at a painful high for many homeowners. But still, the former Prime Minister defends her actions.

This failure of Britain’s elites to properly accept their failings is widespread.

Analysis of Hansard shows that the word 'sorry' across the floor of the House of Commons has dwindled to its lowest level since 2000. Even when it is uttered – as in the case of former Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock's apology at the COVID Inquiry – the sincerity is often justifiably questioned.

Don't miss a story

In the end, empathy – to be of any meaning – needs to be bolstered by a willingness to accept one’s failures. The inability to do so, in the end, impacts the heart of democracy.

Many, disenchanted with the unempathetic political landscape, are distancing themselves altogether from news. Nearly four in 10 adult Brits are reportedly avoiding the news – a ratio that increases the younger they get. Rising inflation, war in Europe, climbing food and rent prices, and the looming threat of climate change have engendered feelings of alienation.

So what to do about this?

Mariame Kaba's wisdom in her book, We Do This ’Til We Free Us, offers a path. Do not fixate on the “spectacular event”, she says. Do not put it higher than “the point of origin”. Instead of aligning uncompromisingly with a singular position, focus instead on addressing foundational problems – and seek to understand what led to the problem in the first place.

We should reconsider empathy, while not the sole driver, as one of the most significant components to achieve such a moral and political view. Its increasing absence in the British political arena is not just problematic but detrimental to the body politic.

As we face this age of extremes, the need for empathetic leadership seems more pressing than ever. We should consider this when gauging who we want to lead us: those who can bait the crowd or those who understand what causes the crowd to be so easily driven to anger.

Philosophy Is Not In Charge of Itself (and other points worth remembering when writing about the state of philosophy)

Are you thinking about writing about the state of philosophy today?

If so, please keep in mind the following facts:

Philosophy Is Not In Charge of Itself

Philosophy at its most influential is still just one of many possible things that influence anything happening in the world, and the world includes philosophy. Thus, philosophy is just one of many possible influences on philosophy. (Other influences include: economics, technology, business, science, culture, geopolitics, human psychology, entertainment, literacy, biology, etc.) This means that not everything that is happening in philosophy is the result of the actions of philosophers and philosophy’s institutions, or is owed to the content of philosophical works. Explanations of what is happening in philosophy that refer only to philosophy or philosophers are going to be incomplete at best, possibly completely mistaken.

Philosophy Is Growing

There are more types of philosophy, on a greater number of topics, in a wider variety of media and formats, created by more kinds of people, for a much broader audience, than ever before in the history of humankind.

“Noticeable” Is Not The Same As “Representative”

What one notices is a function of a variety of factors, and commonality is usually not among them. Rather, we’re inclined to notice things on the basis of difference (contrast with the usual), direction (what we’re told to attend to by existing influences on us), interest (what we already care about), and noisiness (the efforts made by someone to get us to notice them or something they care about). So one should be very careful about making generalizations about something based on what one notices about that thing. (See availability heuristic.)

Readers, do you have other facts to add to this list?

The post Philosophy Is Not In Charge of Itself (and other points worth remembering when writing about the state of philosophy) first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Voice For John Stuart Mill

The biggest winner from the referendum on the weekend is John Stuart Mill.

There’s a strand of left-wing orthodoxy these days that deprecates free speech and brands opposing viewpoints as dangerous wrongthink. This firebrand mode of thinking is excellent at producing an engaged cabal of supporters, but its fruits will often face oblivion in the privacy of one’s own voting booth.

The Yes campaign was undermined by its intellectual siege mentality. In the face of an implacable campaign, only the people already beyond the pale could raise legitimate objections, and so these objections were thought to be invalidated solely by the lack of virtue of those who raised them.

Although John Stuart Mill is a dead white man, the Yes campaigners could do with reading his arguments for free speech and actually engaging with the viewpoints of the opposing side. When political decisions are made privately, it’s better to reduce the fervent engagement of your own tribe to garner more lukewarm support from the other.

The Worst Kind of Listener

The worst kind of listener isn’t the one that is patently distracted (by thumb-flashing smartphone interaction or some endless performative scrolling), cannot make eye contact, shows through their follow-up questions that they weren’t paying attention anyway, rolls their eyes, or indulges in several other variants of not-so-passive aggressiveness.

No, the worst kind of listener is the one who pretends to listen but actually doesn’t. For as you speak, this ‘listener’ emits little, squeaky, emissions of ‘uh-huh, yeah, right, sure’ as you talk, shifting and squirming as you speak as if ants were ascending their pants, and then, as you finish, launches right into their own story, the one that they have not so patiently been waiting to begin telling. You are told, in no uncertain terms that you have merely delayed their speaking. Your time is up; you must exit stage left and let the main act commence.

What makes this performance particularly noteworthy is that such a listener has both distracted you with their patent lack of attention while you speak, for their nodding and grunting is not a sign of comprehension, but rather, a marking of time, one that lets you know how much precious time of theirs you are taking up, and moreover, they have added insult to injury by making clear that nothing whatsoever in what you said has merited any kind of expression of acknowledgement, interest or follow-up.

This kind of listener is a true abomination. As you speak, and unavoidably are distracted by their performative inattention, you find the coherence in your speech fade, as you find yourself, whether you like it or not, speeding up, not so much to finish what you wanted to say, but rather to relieve yourself from having to pay attention to this insulting pantomime. Your thoughts and words, jumbled by irritation and distraction, are no longer worthy to be shared. You amble to the finish line, relieved you don’t have to speak any more. And then watch them hold forth.

Listening is an art; it requires performance, patience, and lots of it. It has an ethical component too; to behave as described above insults the speaker, rendering them minimal respect. If you recognize yourself–as a listener–in this description, it’s not too late to save yourself from the often-unexpressed resentment of your friends, companions, and sundry interlocutors. If you’ve borne the brunt of such behavior, it’s time to speak up in no uncertain terms. We all can do better, and we should.

The unbearable lightness of grey academia: note to self

Wikipedia defines ‘grey literature’ thus:

Wikipedia defines ‘grey literature’ thus:

Materials and research produced by organizations outside of the traditional commercial or academic publishing and distribution channels. Common grey literature publication types include reports (annual, research, technical, project, etc.), working papers, government documents, white papers and evaluations. Organizations that produce grey literature include government departments and agencies, civil society or non-governmental organizations, academic centres and departments, and private companies and consultants.

Some of it is excruciating or just hard to take in. But there you go, no-one mistakes an annual report or many documents for anything less than bland contentless pabulum with some information that might be useful to someone if they know what to look for. And, on the upside, grey literature is often informative and unpretentious. Reports from ABS, BOM and other technical bodies are grey literature.

But there’s an active academic literature that seeks a similar audience. And here’s one formula for the worst of it. You wade into some topical area. You make some distinctions. You deal in ideas that might be the subject of learned investigations in specialist disciplines, but you take things pretty much as given. You might then do some research to get some ‘data’. You might count up the number of a certain type of organisations who have chosen to do Y and how many have chosen to do not Y. You then give talks and consult to said organisations or to those thinking and talking about them.

It’s all kept at a very general level, there are few if any examples and if they are, they’re cursory — illustrative, rather than to interrogate anything. Then you might call for more research. Here is a blog post whipped up from such an approach.

The rise of Knowledge Brokering Organisations (KBOs) has changed how decision-makers access evidence. Whereas in the past, decision-makers might have relied on internal research services, or favoured academics providing them with the latest research, governments across the world have invested in new organisations that can synthesise existing evidence of ‘what works’.

I’ve thought about What Works Centres. Do they work themselves? I have my doubts and set out what they were here. I’d go a little further here and say that they’re a good idea on a napkin. A good beginning to a discussion that might have led to some worthwhile institutional development. But the kinds of issues I’ve raised should have been a live part of their development. For instance, it’s telling that we speak about What Works rather than who made it work or where it worked and where it didn’t. Because it’s likely that, if something difficult is being done, it will be difficult to narrow it down to a stable, replicable ‘what’ and you might like to think more about promoting the agency of those who’ve done things that work. But then that would be more disruptive than putting out lists of decontextualised tips and tricks.

Of course people continue to say things like I said, but very much at the ‘ideas’ level. The What Works Centres themselves don’t seem to be wrestling with them, trying to transform themselves into things that might work better. (Or perhaps they are and I haven’t heard — that would be unsurprising.)

Here’s some more:

KBOs have emerged in countries with different political and policy systems. In all those countries, governments claim a commitment to ‘evidence-based policy-making’ and have invested funding to develop their capacity to use evidence, be that within government itself (for politicians and civil servants) and/or for practitioners such as teachers, doctors.

Explaining their emergence, our interviewees described various drivers, such as a charismatic individual inside or outside government pushing for the need for a new KBO, and the decreasing internal capacity of government and other decision-makers to fill this evidence function. Others spoke of KBOs being created to show that policy-makers cared about an issue and were aware of the lack of good quality evidence in that area.

And on it goes. Half-ideas lie strewn around. Another is social impact bonds. A good idea of sorts, but really only the beginning of something workable and obviously useful.

And on it goes. Reportage as analysis.

I have seen the off-ramp and it works

From my Substack newsletter.

Extraordinary images are being detected within the early pictures taken by the James Webb Space Telescope. As you know, the JWST went in search of exoplanets. Anyway at about the same time I was seeking an AI artist to illustrate the phenomenon of corporate anti-thinking. You know the kind of thing where grown people, some of them quite intelligent sit around and agree on their ‘mission’ and ‘vision’ — each of which can be agreed in an hour’s discussion and expressed in a single short sentence. They then agree on their five favourite values.

Anyway, on applying advanced upscaling technologies NASA scientists are decrypting within JWST images off-ramps from reality on our galaxy’s exoplanets.

Even more exciting, when the castle is upscaled it turns out it’s really a jumping castle.

It’s believed that executives are floating weightless inside the castle, but NASA scientists were reluctant to preempt the results of a probe which is believed to be imminent.

The off-ramp from reality

This post began as an ad for an artist with traditional and AI graphic design skills. If you want to apply, please be my guest. But the post also presents a nice simplification of a way of thinking.

This post began as an ad for an artist with traditional and AI graphic design skills. If you want to apply, please be my guest. But the post also presents a nice simplification of a way of thinking.

Right now I’m wondering how to illustrate what I call “the off-ramp from reality”.

We can be deflected from really looking reality in the eye with wishful thinking. H. A. Simon argues that this happens in corporations.

What managers know they should do — whether by analysis or intuitively — is very often different from what they actually do. A common failure of managers, which all of us have observed, is the postponement of difficult decisions. What is it that makes decisions difficult and hence tends to cause postponement? Often, the problem is that all of the alternatives have undesired consequences. When people have to choose the lesser of two evils, they do not simply behave like Bayesian statisticians, weighing the bad against the worse in the light of their respective possibilities. Instead, they avoid the decision, searching for alternatives that do not have negative outcomes. If such alternatives are not available, they are likely to continue to postpone making a choice. A choice between undesirables is a dilemma, something to be avoided or evaded.

I’d say that, since Simon wrote those words this process has been industrialised by various processes including the specification of ‘corporate values’. Invariably they’ll define them as a list of pleasing expressions. But usually, the real issue is how those values get traded off against each other. An organisation might agree on these three values among others.

- We’re a close-knit team

- We’re always keen to improve

- The customer is always right.

Lots of people will be happy to sign up to all three, but I’d argue that we only really understand the reality of those values when we face the discomfort of how and in what circumstances one would trade one off against the other. Each value will sometimes be impossible to honour without sacrificing one of the other two. Supporting a colleague — always a nice thing in the abstract — might have to give way to the need to improve or satisfy a customer (in each case by reproving or disagreeing with what a colleague has done).

Note — according to an older tradition, the teaching of medical ethics, or the process of applying codes of conduct would focus people precisely on the uncomfortable dilemmas. If you really wanted to explore corporate values at your strategy retreat, you wouldn’t list your favourite values (This always reminds me of Woody’s mother saying to his father “Have it your own way, the Atlantic Ocean is a better ocean than the Pacific Ocean”.) Instead each of the small tables might explore situations where value 1 would be sacrificed for value 2 and vice versa. And why. But I’m unaware of that ever happening and very open to any counter-examples from readers’ experiences.

Thinking you can have all the values is just wishful thinking — and that keeps us away from reality. My post inviting you to the ‘alt-centre’ endorses James Burnham’s assertion that more than nine-tenths of political debate is likewise, just wishful thinking, or in my terms, an invitation to the ‘off-ramp’. ‘Freedom’, ‘equality’, ‘human dignity’ and ‘fairness’ are transcendental/metaphysical values:

From a purely logical point of view, the arguments offered for the formal aims and goals may be valid or fallacious; but, except by accident, they are necessarily irrelevant to real political problems, since they are designed to prove the ostensible points of the formal structure—points of religion or metaphysics, or the abstract desirability of some utopian ideal. … We imagine we are arguing over the moral and legal status of the principle of the freedom of the seas when the real question is who is to control the seas. From this it follows that the real meaning, the real goal and aims, are left irresponsible. …

This method, whose intellectual consequence is merely to confuse and hide, can teach us nothing of the truth, can in no way help us to solve the problems of our political life. In the hands of the powerful and their spokesmen, however, used by demagogues or hypocrites or simply the self-deluded, this method is well designed, and the best, to deceive us, and to lead us by easy routes to the sacrifice of our own interests and dignity in the service of the mighty.

This off-ramp from reality distracts us with chimeras. It takes us to a weightless world in which you don’t have the discomfort of choosing whether you’ll sacrifice this value or that one. So when we get tangled up in arguing for ‘freedom’ or ‘equality’ as transcendent values or just the more mundane organisational values outlined above, we’ve already mostly lost contact with the more uncomfortable reality that these things do not exist in our world as abstract entities, but only ever in concrete situations and they do not appear with any force or clarity except where they are traded off against other things we also value.

There’s another off-ramp that operates not so much through our attraction to comfortable abstractions, but rather through our passions, particularly anger, self-righteousness and contempt. We take this off-ramp when a conversations fail to help us understand others or the world and lead instead to frustration and recrimination. The conversation takes the form of a discussion, but it’s really just an exchange in which two people stay in their own heads and talk past each other. Thus, for instance two people quarrel and each ends up thinking ‘that’s just what they would say’, without really trying to understand where the other is ‘coming from’.

Just as political debate takes the fantasy off-ramp from reality in the form of abstract values, it also takes this darker form. Let’s say you want to argue something about some ideologically contested issue — it might be whether we should be concerned about welfare cheating, or whether corporate tax should be increased or lowered or something more explosive like whether you sign up to a slogan which doesn’t solve some difficult edge case (trans-women are women?). That off-ramp of being accused of bad faith by those you suspect of bad faith won’t be far away. They would say that wouldn’t they?

And so the conversation never gets going. It just sits in preconfigured train tracks. More broadly political debate is mainly preoccupied with framing issues to provoke prejudices — the exact opposite of an engagement with reality and an invitation to thought.

And so to picturing this. …

Here’s the kind of thing I have in mind, though I’ve just put two AI images next to each other in a Powerpoint picture.

The idea is that the person is in the world and could travel somewhere real and find out more about it. But he takes the ‘offramp’ from reality to a fairyland of unicorns, rainbows and I think coloured ballons with people enjoying themselves, and then there’d be either one other pathway leading to reality — or as in the diagram with a number of other pathways.

But I’m discovering that, though AI can be amazingly good at generating some initial image, instructing it with additional text is often inadequate to get it to do what you want. Here’s the attempt of one person who’s worked on this.

The off-ramp and the separate worlds aren’t very clear. Another person I worked with from Upwork who was shown this ended up saying this:

I spent some time trying to generate some of your ideas this afternoon. Unfortunately, I was unable to create the specific concepts with the AI generator I use. I thought I could create the component parts and compile them, but I was unable to execute the basic idea of a highway with an offramp during my trial. … I have been trying to conceptualize how to do it efficiently. I imagine you could create it with a digital painting, which is done by plugging a drawing pad into Photoshop. A person could create the base drawing that way, and then add the AI images behind them : ie paint the highway, paste in an exit sign and billboard from stock, then erase and add or overlay a section of AI fantasy world.

Anyway, you can see roughly the design I’m trying to work towards. It probably requires ‘mixed methods’ of AI generated images then supplemented with human-generated additions all worked on in a graphics program like photoshop. It could be varied — so that there could be a different off-ramp with a more menacing and angry hue to illustrate conversation that gets nasty on social media or perhaps several off-ramps of different kinds in the same diagram.

And there you have it. I hope the some people find the ideas in the post of some value on their own and whether they do or not, that this explains what kind of image I want to work towards.

Fascism wasn’t needed

The attack on the US Capitol Building gave new impetus to an ongoing media debate over whether Donald Trump (and others like him) should be called a fascist. There is a limit to how fruitful debates like this can be, of course. There is no simple rule on how we can use a word. The question is why we want to use it.

Many of those who push for the “fascist” label think it’s the best chance of mobilising people to take a political threat seriously. Nick Cohen argues somewhat along these lines.

On the other hand, many of those who resist the label believe that the wrong diagnosis will lead to the wrong treatment. In this piece, the historian Richard J. Evans points out ways in which Trump differs from Hitler and Mussolini and warns:

rather than fighting the demons of the past — fascism, Nazism, the militarised politics of Europe’s interwar years — it is necessary to fight the new demons of the present: disinformation, conspiracy theories and the blurring of fact and falsehood.

It was pointed out to me that Evans fails to mention racism in this connection. That is a troubling oversight. For many, that is the heart of the Trumpist threat and the main reason for conjuring the demons of the past around it. In How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, the philosopher Jason Stanley writes:

The dangers of fascist politics come from the particular way in which it dehumanizes segments of the population. By excluding these groups, it limits the capacity of empathy among other citizens, leading to the justification of inhumane treatment, from repression of freedom, mass imprisonment, and expulsion to, in extreme cases, mass extermination.

Stanley is aware that “many kinds of political movements involve such a division; for example, Communist politics weaponizes class divisions”. But, he goes on, fascist politics specifically creates division by “appealing to ethnic, religious, or racial distinctions”.

His book is mostly about contemporary movements. Almost all the references to historical fascism, however, are to National Socialism. The first chapter, on appeals to “the mythic past” and traditional family values, quotes a Mussolini speech — “we have created our myth”. But the myth referred to by Mussolini is not explicitly linked with the past. And Mussolini’s fascism, while it emphasised tradition, presented itself as driving forward into the future more than falling back into the past. Mussolini supported traditional values only insofar as they served his religion of the State, and his support was transparently pragmatic.

By contrast, Stanley is able to draw on a wealth of Nazi statements to support his characterisation. He has Alfred Rosenberg directly referring to Germany’s “mythical past” (the same as Luther had done). He has Gregor Strasser and Paula Siber celebrating traditional gender roles. Etc. For Nazism, his story makes perfect sense.

This pattern continues throughout the book. When Stanley seeks historical precursors to the type of fascism he describes, the best fit is always with the Nazis. References to other types of fascism are rare and on points of extreme abstraction, for instance an Italian fascist magazine is quoted saying that: “The mysticism of Fascism is the proof of its triumph”.

Why is this important? What distinguished Nazi fascism was the foundational character of its racism. Mussolini exploited racism, but again he thought that each nation should promote its own ideal racial type, leading to an endless struggle – struggle is the very essence of human history, blah blah blah. The Nazis thought that the world should be dominated by one racial type. Their goal was not endless struggle for its own sake but a final resolution of perfect domination — a pax Aryana.

This is important because there was one historical example that particularly inspired and emboldened them. It was the example of the United States of America.

Carroll Kakel’s book, The American West and the Nazi East, documents how Hitler’s doctrine of Lebensraum was an imitation of the American conquest of its Western frontier. The extermination of the Slavs was conceived in imitation of the extermination of North America’s native population. It showed the Nazis what Aryan peoples could achieve. Similarly, James Whitman’s Hitler’s American Model examines how the Nuremberg Laws were modelled on the Jim Crow laws and, more generally, how the idea of codifying racial domination into law was inspired by American examples. Americans might be surprised to learn that in some cases the Nazis found the model too extreme. Stanley also documents the American precursors to fascist tactics, drawing on W.E.B. Du Bois’ descriptions of paramilitary violence and segregationist laws in Black Reconstruction in America. Nor is it simply that the ideas that inspired the Nazis reside in America’s past. As Sandy Darity and Kirsten Mullen argue, many times the nation was presented with a subsequent opportunity to partially right the wrongs of the past, a different path was taken instead.

Given this, I wonder how the word “fascism” functions in America’s self-awareness.

“Fascism” is a very European-sounding word. It was invented by an Italian and inspired by an image from the Roman Empire — the most European of all institutions. But the elements of Trumpism that most resonate with Nazism were in America long before — that is, to some extent, where the Nazis got the idea. One danger in Americans using the term “fascism” is that it allows them to write off their own philosophies as foreign imports.

The truth is that, for dehumanization of segments of the population, fascism wasn’t needed. Even if we follow Robert Paxton’s suggestion and trace the birth of fascism to the Ku Klux Klan, the Klan were formed to enforce a racial contract signed long before they appeared. We could consider Jamelle Bouie’s suggestion that “Colonial domination and expropriation marched hand in hand with the spread of ‘liberty,’ and liberalism arose alongside our modern notions of race and racism”. The racial dehumanisation that inspired fascists preceded them. It didn’t require suspension of the rule of law; it was built into the rule of law. It didn’t require an attack on democracy; it was popular with voters. It didn’t require demagogues with explosive rhetoric; staid bureaucrats and ‘safe pairs of hands’ did the job just fine. Get rid of fascism, and you can keep most of what is blamed on it, since those things were there long before it.

Many of the mob that stormed the Capitol Building were inspired by Nazis. Many were adorned in Nazi symbolism. Many, no doubt, turned excited images of the Beer Hall Putsch over in their minds. But to see the building invaded by forces inspired by some Germanic ideology is to forget that this ideology borrowed plans conceived within that very building.

I’m not accusing those who use the term “fascist” of forgetting this. But still I worry about the effects of the term. Most people, when they hear “fascism” think of Hitler. You can hardly hear the term without drawing the little moustache in your mind. Fewer will think of Jim Crow or the Klan. Fewer again will think of Andrew Jackson and the Manifest Destiny.

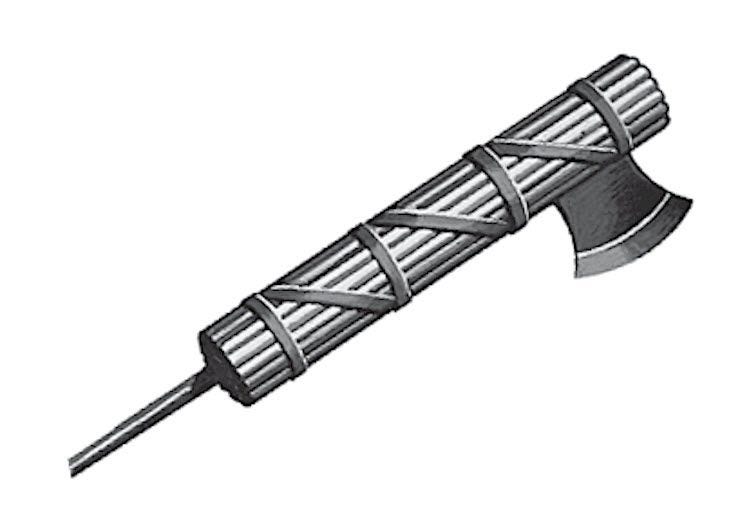

And is fascism really the problem? Not only does the word sound foreign; the system is top-down. The fasces image represents strength in unity. The fasces with the axe — the version favoured by Mussolini — denotes what the Romans called a dictator. A dictator, at least in the popular imagination, imposes his will from above. Hitler is the dictator to whom the dehumanising racism of the Third Reich — with its forced labour, mass imprisonment, and extermination — can be traced, rightly or wrongly.

But what about the dehumanising acts permitted and imposed in America’s history? These were not brought in by dictators wielding emergency powers. They bubbled up from the bottom rather than being imposed from the top. They were brought in through the constitution and the rule of law, not by suspensions of it. What the Axis powers wanted, of course, was the sort of empire that the Allies had acquired without fascism.

It is possible, I submit, that we commit these sorts of acts because we want to, not because some political system drives us to them. We don’t need any ideology either. People just like this stuff; it’s a crowd-pleaser. In any case, fascism isn’t needed to prompt it. In fact, when fascists tried to emulate the American example, they were ultimately destroyed, rather than ascending into hegemony. Fascism may well have got in the way.

Book at Lunchtime: Jews, Liberalism, Antisemitism

Book at Lunchtime is a series of bite-sized book discussions held weekly during term-time, with commentators from a range of disciplines. The events are free to attend and open to all. About the book:

The emancipatory promise of liberalism - and its exclusionary qualities - shaped the fate of Jews in many parts of the world during the age of empire. Yet historians have mostly understood the relationship between Jews, liberalism and antisemitism as a European story, defined by the collapse of liberalism and the Holocaust. This volume challenges that perspective by taking a global approach. It takes account of recent historical work that explores issues of race, discrimination and hybrid identities in colonial and postcolonial settings, but which has done so without taking much account of Jews. Individual essays explore how liberalism, citizenship, nationality, gender, religion, race functioned differently in European Jewish heartlands, in the Mediterranean peripheries of Spain and the Ottoman empire, and in the North American Atlantic world.

Speakers:

Professor Abigail Green is Professor of Modern European History at Brasenose College, Oxford. Her recent work focuses on international Jewish history and transnational humanitarian activism. She is currently completing a three year Leverhulme Senior Research Fellowship, working on a new book on liberalism and the Jews, tentatively titled Children of 1848: Liberalism and the Jews from the Revolutions to Human Rights. Working in partnership with colleagues in the heritage sector, she is also leading a major four year AHRC-funded project on Jewish country houses.

Professor Simon Levis Sullam is Associate Professor of Modern History at Ca’ Foscari, University of Venice, Italy. His fields of interest include the history of ideas and culture in Europe between the Nineteenth and the Twentieth century, with a particular focus on nationalisms and fascism; the history of the Jews and of Anti-Semitism; the history of the Holocaust; the history of historiography, and questions of historical method. His many publications include, most recently, The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy.

Professor Adam Sutcliffe is Professor of European History and co-director of the Centre for Enlightenment Studies at King’s College London. His research has focused on in the intellectual history of Western Europe between approximately 1650 and 1850, and on the history of Jews, Judaism and Jewish/non-Jewish relations in Europe from 1600 to the present. Professor Sutcliffe’s most recent publication, What Are Jews For? History, Peoplehood and Purpose, is a wide-ranging look at the history of Western thinking on the purpose of the Jewish people.

Dr Kei Hiruta is Assistant Professor and AIAS-COFUND Fellow at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies, Aarhus University, Denmark. His research lies at the intersection of political philosophy and intellectual history, with particular interest in theories of freedom in modern political thought. His book Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin: Freedom, Politics and Humanity will be published from Princeton University Press in autumn 2021.