philosophy

Why is Political Philosophy not Euro-centric?

In a recent post about unfair epistemic authority, Macarena Marey suggests that

In political philosophy, the centre is composed of the Anglophone world and three European countries…

One can think of “the center” in terms of people or of topics. Although Marey’s post is clearly about philosophers not philosophies, and I agree with her, one can also address the issue of “the centre” about philosophies.

For my part, I wonder the opposite: how come political philosophy is not Euro-centric? If Anglophone and European philosophers dominate the field, as indeed they do, why doesn’t European politics dominate political philosophy, too?

My point is not that European politics should dominate political philosophy, but that it is surprising that it does not. First, because philosophers often sought solutions to the political problems of their time (think of Montesquieu or Locke on the separation of powers; of Paine and Burke debating human rights during the French Revolution etc.). Second, because the European Union is a political innovation on many respects; had a philosopher presented the project (“imagine enemies at war pooling their resources”), it would have been dismissed as utopian. Finally, because EU is a complex organization which deals with enough topics that it is hard not to find yours. Topical, innovative, and complex – but not of interest for European hegemonic philosophers: is this not puzzling?

You doubt. But how would political philosophy look like if it was Euro-centred? Certainly, renewed — by philosophical views tested at the European level or inspired by the European institutions. For example, there would be philosophical analyses of “new” topics such as:

- Freedom of movement – a founding freedom of the European union over the last 70 years. Surprisingly, there is not a single philosophical treaty on this freedom today (although freedom of speech, of assembly etc. are well represented); all philosophical studies reason as if it were natural to control immigration, as if open borders were an unrealistic utopia – in short, as if the EU did not exist (neither Mercosur‘s or African Union‘s institutions).

- Distributive justice between states or within federal states – a political reality since the 1950s or earlier. But since the 1970s, philosophers have been praising Rawls, Walzer, and others who argue that redistribution between states is not a matter of justice (no reviewer have ever asked them whether the existing European/international redistribution was unjust etc.).

- Justice of extending / fragmenting states and federations of states – today, cosmopolitanism is considered in opposition to nationalism, not to regionalism or federalism; secession/ unions are under-discussed in theories of justice or critical race theory; there are more philosophical studies on just wars than on peace etc.

Many other sources of philosophical renewal are not specific to the European Union but could have been be activated if political philosophy was Euro-centric. For example, international aid has been institutionalized since the WWII (as I have briefly shown here), but prominent philosophers reason about its justice as if it did not exist. Less prominent philosophers should adapt to the existing terms of the debate.

In short, if political philosophy was a little more Euro-centric, its questioning would be renewed and more realistic. If it is not, the problem of political philosophy is not “Euro-centrism” but “centrism” tout court: we tend to organize around a few “prominent philosophers” and their views rather than around originality, pluralism, and truth.

My experience with geopolitics of knowledge in political philosophy so far

Geopolitics of knowledge is a fact. Only few (conservative) colleagues would contend otherwise. Ingrid Robeyns wrote an entry for this blog dealing with this problem. There, Ingrid dealt mostly with the absence of non-Anglophone colleagues in political philosophy books and journals from the Anglophone centre. I want to stress that this is not a problem of language, for there are other centres from which we, philosophers from the “Global South” working in the “Global South”, are excluded. In political philosophy, the centre is composed of the Anglophone world and three European countries: Italy, France, and Germany. From my own experience, the rest of us do not qualify as political philosophers, for we are, it seems, unable to speak in universal terms. We are, at best, providers of particular cases and data for Europeans and Anglophones to study and produce their own philosophical and universal theories. I think most of you who are reading are already familiar with the concept of epistemic extractivism, of which this phenomenon is a case. (If not, you should; in case you don’t read Spanish, there is this).

Critical political philosophy is one of the fields where the unequal distribution of epistemic authority is more striking. I say “striking” because it would seem, prima facie, that political philosophers with a critical inclination (Marxists, feminists, anti-imperialists, etc.) are people more prone to recognising injustice than people from other disciplines and tendencies. But no one lives outside a system of injustice and no one is a priori completely exempt from reproducing patterns of silencing. Not even ourselves, living and working in the “Global Southern” places of the world. Many political philosophers working and living in Latin America don’t even bother to read and cite their own colleagues. This is, to be sure, a shame, but there is a rationale behind this self-destructive practice. Latin American scholars know that their papers have even lesser chances of being sent to a reviewing process (we are usually desk-rejected) if they cite “too many” pieces in Spanish and by authors working outside of the academic centre.

In many reviews I’ve received in my career, I have been told to cite books by people from the centre just because they are trending or are being cited in the most prestigious Anglophone journals, even if they would contribute nothing to my piece and research. I have frequently been told by reviewers to give more information about the “particular” social-historical context I am writing from because readers don’t know a lot about it. This is an almost verbatim phrase from a review I got recently. I wonder if readers of Anglophone prestigious, Q1 journals stop being professional researchers the instant they start reading about José Carlos Mariátegui or Argentina’s last right-wing dictatorship. Why can’t they just do the research by themselves, why should we have to waste characters and words to educate an overeducated public? This is as tiresome as it is offensive. When I cite the work of non-Anglophone authors from outside of the imperial centres (UK, USA, Italy, Germany, and France, no matter the language they use to write), reviewers almost always demand that I include a reference to some famous native Anglophone (or Italian / German / French, without considering gender or race; the power differential here is simple geographical procedence) author who said similar things but decades after the authors I am quoting. I’ve read all your authors. Why haven’t they read “mine”? And why do they feel they have to suggest something else instead of just learning about “our” authors? This is what I want to reply to the reviewers. Of course, I don’t. I dilligently put the references they demand. I shouldn’t have to, but if I don’t, I don’t get published. There’s the imperial trick again.

English is also always a problem, but not for everyone who is not Anglophone. In 2020 I was in London doing research at LSE. I attended a lecture by a European political theorist. They gave the talk in English. Although they work at a United Statian University, their English was poor. The room was packed. The lecture was mediocre. I was annoyed. “Why do they feel they don’t have to make an effort to pronounce in an intelligible way?”, I thought. When I speak they don’t listen to me like that, with concentrated attention and making an effort to understand me. The reason is in plain view: coloniality of power. If you come from powerful European countries, you don’t need to ask for permission. You don’t need to excel. You don’t need to have something absolutely original to say. You just show up and talk. If you are from, let’s say, Argentina, and you work there (here), you have to adapt to the traditional analytic way of writing and arguing so typical in Anglophone contexts, including citing their literature, if you want to enter the room in the first place. You are not even allowed to use neologisms, although the omnipresent use of English as a lingua franca should have already made this practice at least tolerated. One cannot expect everyone to speak English and English to remain “English” all the same. Inclusion changes the game, if it doesn’t, then it is not isegoria what is going on but cultural homogenisation. (Here is a proposal for inclusive practices regarding Enlgish as a lingua franca). The manifest “Rethinking English as a lingua franca in scientific-academic contexts” offers a detailed critique of the idea and imposition of English as a lingua franca. I endorse it 100 %. (Here in Spanish, open access; here in Portuguese).

In my particular case, I am frequently invited to the academic centre, sometimes to write book chapters, encyclopaedia entries, and papers for special issues, sometimes to give talks and lectures. Not once have I not thought it was not tokenism. Maybe it is my own inferiority complex distorting my perception of reality, but we know from Frantz Fanon which is the origin of this inferiorisation.

I used to be pretty annoyed by this whole situation until I realised that I don’t need to try to enter conversations where I am not going to be heard, understood, or taken seriously. The fact is that we don’t need to be recognised as philosophers by those who willingly ignore our political philosophy. And this is why it is hard for me to participate in forums such as this blog. I just don’t want to receive the same comments I get when I send a paper to an Anglophone, Q1 journal, to put it simply.

But I also want to keep trying, not to feel accepted and to belong, but because I do believe in transnational solidarity and the collective production of emancipatory knowledge. It is a matter of recognition, and a question of whether it is possible for the coloniser to recognise the colonised, to name Fanon once more.

Michael Polanyi in 1960 on Teilhard de Chardin on evolution

Michael Polanyi was highly suspicious of the hyper-reductionism of neo-Darwinism. It’s reduction of the evolution of a thing so vast as life into a single causal mechanism. And it was a good call.

Darwin himself had proposed that natural selection was a major mechanism of evolution, but not the only one. He was good with the existence of Lamarckian mechanisms, which was a pretty good call given that they keep turning up. But neo-Darwinism held that there was just one mechanism behind evolution — genetic variation — and that this was driven exclusively by random mutation. It’s worth pondering the hankering for closure this claim embodies. Why the enthusiasm to shuffle such mechanisms off the scientific stage.

Neatness is one reason. Arrogance another. Laying down the law on the grounds that you’re uniquely qualified to pontificate about them is inherently satisfying to many. There’s also a doubling down on driving purpose out of evolution. And that’s something science had been doing since the scientific revolution — driving our Aristotelian notions of telos from biology. And that was also driving God out of biology. All good if God is seen as some imposition — some being intervening in the universe whenever he wants to vote someone off the island.

The thing is, immanent purpose is an obvious fact of biology. The heart has the purpose of pumping blood. It’s designed to pump blood. That doesn’t mean it has an intelligent designer watching on, occasionally reaching for their remote. But it does mean that it was designed. It was designed immanently. We’ve known for a long time that the immune system works this way — it creates a randomising process of experimentation and then puts its thumb on the scales by amplifying the more promising experiments. (This is the way social media is driving our species to conflict — only where the immune system is part of a healthy emergentism (at least from our point of view, and depending on your values, from the universe’s) the immanent design in social media is, at least in the first instance regressive, leading us down the brainstem towards lower levels of capability and organisation. Perhaps over time we will evolve ways of using its potential positively.

In any event the idea of systems of “directed chance” and the ‘emergentism’ that naturally arises from it fascinated Polanyi and lay as one of the core elements of his philosophy of science and of humanity.

Which meant that I was fascinated and impressed by this brief review.

An Epic Theory of Evolution

THE SUCCESS of “The Phenomenon of Man,” by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin is a mystery and a portent. … I have seen a dozen reviews highly praising it and have noticed no adverse criticism. I, myself, had readily turned to Teilhard, since I reject the current genetical theory of evolution and had no doubt that Teilhard rejects it too.

But what about all those who so eagerly read and praise the book? Does their acclaim mark the rise of a vast underground movement, sweeping aside the writers and readers who had shortly before accepted the worldwide pronouncements made on the occasion of the Darwin centenary? Where was the public now applauding Teilhard when Sir Gavin de Beer declared that modern genetical research has “established as firmly as Newton’s laws of motion that hereditary resemblances are determined by discreet particles, the genes, situated in the chromosomes of the cells. . . “? Can this be reconciled with Teilhard’s teachings?

Puzzled by these questions, I kept fingering my copy of Teilhard’s English’ translation and finally looked through Julian Huxley’s introduction. In it he praises Teilhard’s work highly and, indeed, claims to have largely anticipated it. Yet it was Sir Julian’ Hpdey who prefaced one of thentost authoritative statements of current selectionist theory (“Evolution as a process”) with the words: “A single basic mechanism underlies the whale organic evolution—Darwinian selection acting upon the genetic. mechanism.”

Teilhard declares: “We do not yet know how characters are formed, acumulated and transmitted in the secret recesses of the germ cell.” In his view, “the blind determinism of the genes” plays but a subordinate part: “We are dealing with only one event,” he says, “the grand orthogenesis of everything living towards a higher degree of immanent spontaneity.” “The progressive leaps of life” must be interpreted “in an active and finalistic way.”

This active striving towards ever higher, more vividly conscious forms of existence, which eventually achieves responsible human personhood and establishes through man a realm of impersonal thought, is the dominant theme of “The Phenomenon of. Man.” . . ‘This image is.very different from that of the repeated failures of precision in the self-copying of Mendelian genes, to which Huxley and the rulihg orthodoxy attribute evolution. It is precisely the kind of theory violently condemned by this orthodoxy for trying to explain evolution by some inherent bias, guiding the direction mutations take. Admittedly, Teilhard’s wording is vague.…

Teilhard’s way r of shrugging aside any question concerning the mechanism of heredity also casts a veil of obscurity tn the foundations of his position. And this is how he avoids an explicit attack on genetical selectionism and also feels entitled to use, without more than the most cursory acknowledgment, the ideas of Samuel Butler, Bergson, and others who have previously interpreted evolution in his way.

And yet in these shortcomings we discover the secret of Teilhard’s achievement and success. He is a naturalist and a poet, endowed with contemplative genius. He refuses to look upon evolution like a detached observer who reduces experience to the exemplification of a theory. Instead he stages a dramatic action of which ‘man is both a product and a responsible participant. His purpose is to rewrite the Book of Genesis in terms of evolution. The thousand million years of evolution are seen here as one single act of cre-ative power, like that revealed by Genesis.

This creative act is inherent in the universe. By producing sentient beings the universe illuminates itself, and through human thought it gradually achieves communion with God. Teilhard uses scientific knowledge merely as a factual imager* in which to expound his vision. His work is an epic poem that keeps closely to the facts. Gaps in the factual imagery of a poem can be safely left- open. So there is no need for the author to argue with selectionism.

As a poet, Teilhard stands powerfully apart and commands assent from many who continue to hold views that are incompatible with his vision; and this is how his work is startlingly novel though it contains few new ideas. . But would Teilhard’s poetry have received such warm response fifty years ago? No, its contemporary success, is a portent. There is a tide of dissatisfaction mounting up against scientific obscurantism. Book after book comes out aiming against the scientific denaturation of some human subject.

Teilhard owes his present success to this movement. But, unfortunately, this has made his success a little too easy. I do not believe that the origin and- destiny of-man can be defined in such vague terms. A text that is so ambiguous that people whose views on its subject matter are diametrically opposed can read it with equal enthusiasm cannot be wholly satisfying. And I suppose that this is why, in spite of its many insuring and luminous passages, it is tedious to read ‘the book from cover to cover. Having avoided so many decisive issues, it can serve only as a new and powerful pointer towards problems that it leaves as unsolved as before.

Read the full review here.

Philosophy You Liked Published in 2023

The year is coming to a close, and so it’s a good time for year-end lists, and Daily Nous is a good place for a year-end list about good philosophy.

I’m not asking you about “the best” new philosophy you read. The idea that we could make such fine-grained comparisons of philosophical quality is doubtful. Plus, it puts too much pressure on people answering, making the exercise less fun.

So let’s keep it relaxed and low stakes. Of the philosophy you read—articles, chapters, or books—published in 2023, which did you like and would recommend others read?

When answering, please follow these guidelines:

- just one or two suggestions each, please

- don’t recommend your own writing

- the works you suggest should have 2023 publication dates

- add a line or two saying what you liked about each work you mention

- include links to the works, if possible

- use your real name (at least your first name) and a verifiable email address (your email address won’t be published)

I’m looking forward to seeing your suggestions.

Posting will be light over the next week.

The post Philosophy You Liked Published in 2023 first appeared on Daily Nous.

What the Evidence Says about whether Studying Philosophy Makes People Better Thinkers

It says: “we need more evidence.”

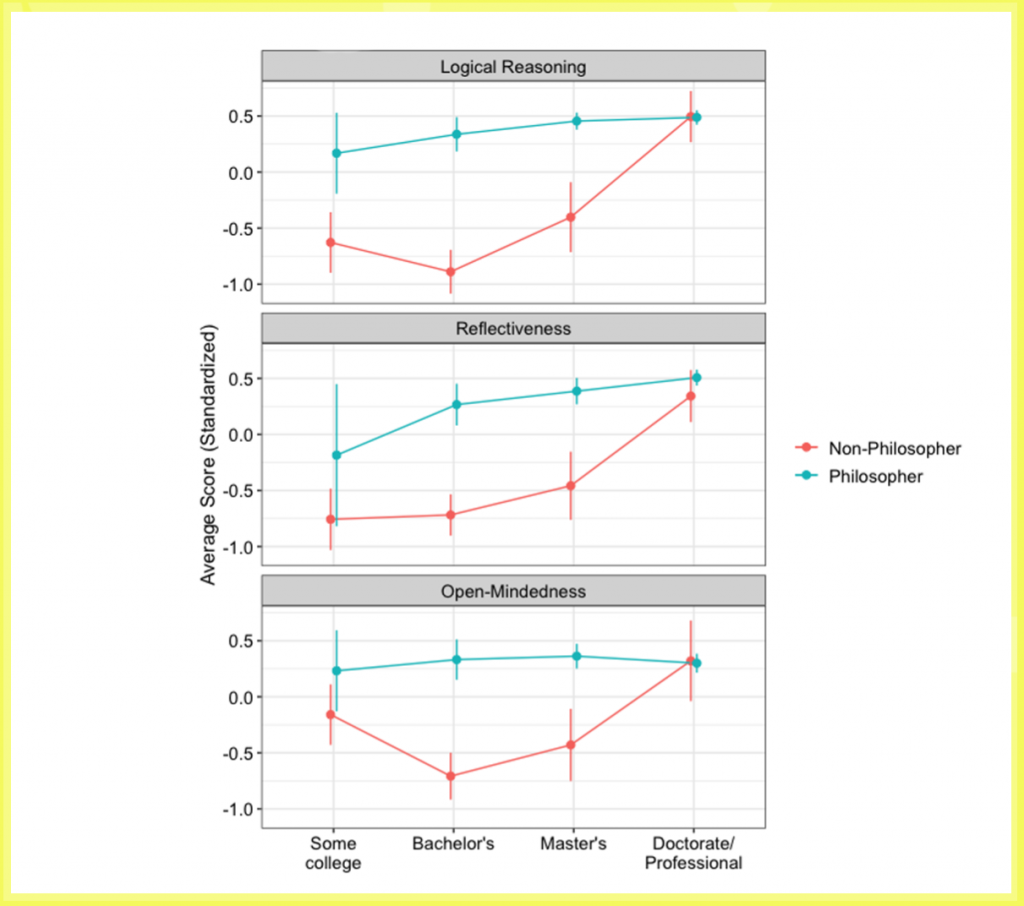

Evidence indicates that “on average philosophers are better at logical reasoning, more reflective, and more open-minded than non-philosophers.” Philosophers are more “intellectually virtuous,” as they put it (except at the highest levels of education):

Figure 1 from “Does Studying Philosophy Make People Better Thinkers?” by Michael Prinzing & Michael Vazquez. “Logical reasoning ability, reflectiveness, and open-minded thinking, grouped by philosophical training. Points indicate means and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The y-axis has been standardized for ease of comparisons across measures. Hence, 0 indicates the average; 1 indicates one standard deviation above average, etc.”

Yet the correlation between philosophical education and these intellectual virtues does not explain the matter of causation. It could be that studying philosophy leads people to be better thinkers in these ways (that is, the correlation is explained by treatment effects), or it could be that philosophical study attracts people who already have these qualities (that is, the correlation is explained by selection effects), or some combination.

To help settle the matter, Prinzing and Vazquez compared students during the first week of an introductory philosophy class with the general population of adults in the U.S. They write:

One strategy for investigating the question of treatment versus selection effects is to assess students right as they start their first philosophy course. If students at the very beginning of their philosophical education are no different from their peers, or from the population at large, then the differences we’ve observed between philosophers and non-philosophers might be due to a treatment effect. On the other hand, if those students already score substantially higher than others, then the differences we have observed are likely due primarily if not entirely to selection effects.

The data they collected suggest that self-selection may explain the prevalence of the intellectual virtue of “reflectiveness” among those who’ve studied philosophy, while studying philosophy may indeed lead students to develop or improve the intellectual virtues of “open mindedness,” being able to “see things from another’s point of view,” and being able to “imagine what an impartial third party might think about their situation.” When it comes to the quality of “intellectual humility,” the evidence was, appropriately enough, inconclusive.

Prinzing and Vazquez also looked at findings from a study on how students’ thinking changes during an ethics course, comparing the ethics students with psychology students at the beginning and end of a semester. They write:

The results indicated that the philosophy students changed their views on [ethical questions covered in the course], and more so than the psychology students. Additionally, the researchers found that the philosophy students, but not the psychology students, showed a reduced tendency to base their ethical views on intuition and emotion versus deliberation and analysis. Among philosophy students specifically, the degree to which students reduced their reliance on intuition and emotion predicted the degree to which they changed their ethical beliefs. This is an exciting set of results, both because it suggests that philosophy courses influence the way that people think about real-world issues, and also because it suggests that the mechanism behind these changes is a trait that we know philosophers display to a remarkably high degree (i.e., a tendency to engage in reasoning and reflection).

Furthermore,

The philosophy students… became more inclined to think that it is morally wrong to: “trust your intuitions without rationally examining them,” hold “on to beliefs when there is substantial evidence against them,” or “rely on anything else other than logic and evidence when deciding what is true” (these are quotes from the survey questions). This is evidence of a treatment effect.

They add: “Whether it is a desirable treatment effect, on the other hand, is less clear.”

The authors also include in the paper some thoughtful remarks about the extent to which philosophical skills may (or may not) transfer to other domains.

In the end, though, the results are inconclusive:

The primary takeaway from our review of empirical evidence, therefore, is that there simply isn’t enough of it. If we want clearer evidence, it seems likely that we will need to gather it ourselves. For this reason, we urge philosophers to begin collecting data that can provide evidence for treatment effects.

The full paper is here.

Related: “Philosophy Majors & High Standardized Test Scores: Not Just Correlation” by Thomas Metcalf (Spring Hill), which Prinzing and Vazquez critically discuss in their paper.

The post What the Evidence Says about whether Studying Philosophy Makes People Better Thinkers first appeared on Daily Nous.

Conservatism in Political Philosophy

“On the surface it is deeply puzzling that conservatism has disappeared from professional philosophy.” So writes Eric Schliesser (Amsterdam) in a post at Digressions & Impressions. He explains his puzzlement, but the main aim of his post is to provide an explanation for conservatism’s absence from contemporary political philosophy.

What do we mean by “conservatism”? Let’s not confuse political philosophy with political parties. “Conservatism” in political philosophy is no more accurately described by reference to the views of the typical self-identifying conservative voter than “liberalism” in political philosophy is accurately described by reference to the views of the typical self-identifying liberal voter. Rather, conservatism here is the conservatism of Burke, Oakeshott, and others. Schliesser elaborates:

Conservative political philosophy has an originating thought that goes something like this: political life is centered on groups or collectives that need to use violence to constitute and maintain themselves and, thereby, establish order…. [An] important consequence of the originating thought is that the order established can allow one to pursue the common good. That is to say, the conservative rejects the idea that the state must be neutral. Of course, the content of the common good is deeply contested even among conservatives (including among ones where one may, say, expect agreement, say Catholics)—some of the fiercest debates involve the role of religion and the status of the church or rites in this common good…. [T]he interest in the common good explains the conservatives’ special interest in institutions that help secure shared morality: education, family, religion, civic culture, etc. Or in institutions that help secure a certain commons sensibility: aesthetics, the arts, literature, etc.

He then offers two explanations for the relative lack of conservatism in political philosophy today. It’s worth noting he explicitly acknowledges externalist explanations, such as: the absence of conservatism may be owed to the lack of conservatives, which may be owed at least in part to conservatives not feeling sufficiently welcome in academia to pursue a career in it, or to political discrimination and bias in philosophy. But his focus in the post is on whether there are explanations that stem from conservative political philosophy itself. His two explanations are:

- Conservatives reject the terms of the debate among liberals vs Marxists and liberals vs libertarians. They are suspicious of what we may call ‘rights first’ accounts without accompanying obligations, and (more important) they reject the idea that the point of political life is to secure rights.

- Conservatism has an an instinctive mistrust of systematicity…. [T]hat raises an important problem…: working out what, say, Thomism or Right Hegelianism might mean today generally involves (i) a hermeneutic aspect, (ii) a reconstructive aspect, and (iii) a constructive (forward-looking) aspect. But the norms of the discipline in analytic philosophy today treat (i-ii) as ‘history.’ And while many normative theorists are interested in some historical figures, they have little appetite for engagement with (i) and (ii). And so taken as self-standing (iii) looks entirely ungrounded or unprincipled, that is, ‘bad philosophy,’ compared to the systematic rigor of utilitarianism and the method of reflective equilibrium of the Rawlsian.

See his post for the details.

I think Schliesser is on to something, particularly with #2, but there are at least two other explanations, which we can label “political speciation” and “pragmatic traditionalism”.

“Political speciation” is the idea that various parts of conservatism have been split off from it and developed into alternative views. For example, libertarianism can be seen as picking up on conservative elitism, subsidiarity, and appreciation of the dangers of political power. Marxism shares with conservatism its emphasis on the importance of history, the influence of institutions on human life, a normative conception of human nature, a discounting of the importance of justice, and a focus on the common good.

Speaking of the common good, remember communitarianism? Schliesser’s description above of conservativism’s focus on the common good could have been written about communitarianism. And I would venture that among contemporary political philosophers, the one who has gotten the most people to take seriously conservative political ideas is not the one proud conservative actually playing the political philosophy game (John Kekes) but “communitarian” Michael Sandel (Harvard). He will deny he is a conservative—fine—but look at how much overlap there is between conservatism and ideas he has put forward: the priority of the common good in political philosophy, the immorality of market commodification, a caution to appreciate what nature hands us rather than mess with it, a romanticization of the past.*

So if you’re looking for conservatism in contemporary political philosophy, you may not find it intact, but you will see elements of it in a variety of other views.

By “pragmatic traditionalism” I mean to emphasize the aspect of conservatism that is about valuing and preserving existing practices. This is tied to skepticism not just of, as Schliesser says, “systematicity,” but of abstract reasoning about practical matters. I take an important element of conservatism to be the view that knowledge about good lives, good communities, and good societies is not mainly, if at all, the product of a priori and hypothetical reasoning, but of observation of the practices which enable us to survive and flourish. Such practices embed knowledge that is not necessarily articulable by those engaged in and benefitting from them. If the knowledge is not articulable, how do we know it’s there? Because, despite our corruptible natures and limited understanding and agonistic inclinations, we are still here. Hence the importance of keeping things largely as they are, and being very slow and cautious about change. As Oakeshott famously says in “On Being Conservative”:

[W]henever there is innovation there is the certainty that the change will be greater than was intended, that there will be loss as well as gain and that the loss and the gain will not be equally distributed among the people affected; there is the chance that the benefits derived will be greater than those which were designed; and there is the risk that they will be off-set by changes for the worse.

From all of this the man of conservative temperament draws some appropriate conclusions. First, innovation entails certain loss and possible gain, therefore, the onus of proof, to show that the proposed change may be expected to be on the whole beneficial, rests with the would-be innovator. Secondly, he believes that the more closely an innovation resembles growth (that is, the more clearly it is intimated in and not merely imposed upon the situation) the less likely it is to result in a preponderance of loss. Thirdly, he thinks that the innovation which is a response to some specific defect, one designed to redress some specific disequilibrium, is more desirable than one which springs from a notion of a generally improved condition of human circumstances, and is far more desirable than one generated by a vision of perfection. Consequently, he prefers small and limited innovations to large and indefinite. Fourthly, he favors a slow rather than a rapid pace, and pauses to observe current consequences and make appropriate adjustments. And lastly, he believes the occasion to be important; and, other things being equal, he considers the most favorable occasion for innovation to be when the projected change is most likely to be limited to what is intended and least likely to be corrupted by undesired and unmanageable consequences.

So it’s not just that conservatives “reject the terms of the debate.” They reject the methods. An intellectual environment dominated by a priori claims and intuitions, in which empirical questions are “merely technical” matters to be dealt with later and by others, and in which something’s being traditional is not itself a reason in its favor—that is not, from the conservative point of view, conducive to wisdom about the political. And in turn, the inherently empirical and historical and cautious aspects of conservative political philosophy comprise a methodology that is alien to a community that believes it can conjure human flourishing from mere ideas and sees the past mainly as a museum of injustice.

But political philosophy is changing. We’ve had two decades of people arguing in favor of various forms of “non-ideal theory.” Efforts at demographic inclusiveness and canon expansion raise awareness of the geographic and historical situatedness of ideas. There seems to be more and more work on political epistemology and intellectual humility. The discipline is more open to critical race theory, which could be described as focusing on the interplay between social roles and institutional power. And philosophy seems to be becoming more religious.** So, from a high enough altitude, it looks like the landscape is changing in ways that, perhaps surprisingly, creates openings for conservatism—or at least for parts of it, here and there.

* Note that even when disguised as a kind of soft-left-anti-liberalism, these conservative ideas failed to gain much lasting support among political and moral philosophers.

** One piece of evidence for this, pace warnings about comparing the results, is the increase from 2009 to 2020 in PhilPapers survey respondents supporting theism. “Accept/Lean to Theism” went up from 14.6% to 18.93%, while “Accept/Lean to Atheism” went down from 72.8% to 66.95%. [Update: See the comment from David Wallace on this data. Also, in the sentence to which this note is attached, I changed “is” to “seems to be”.]

The post Conservatism in Political Philosophy first appeared on Daily Nous.

Philosophy’s Importance in “Times Like These”

The Los Angeles Review of Books has just concluded publishing a series of articles on the importance of philosophy in “times like these”.

What are “times like these”? The editor of the series, George Yancy (Emory), describes them as “trying times… moments of existential ruin, where we are 90 seconds to midnight, which is the closest we have ever been to global catastrophe.”

The contributors to the series are Elizabeth Brake (Rice), Lori Gallegos (Texas State), Jay Garfield (Smith), Kate Manne (Cornell), Todd May (Warren Wilson), and Vanessa Wills (George Washington). You can find the links to each of their pieces in the last two paragraphs of Professor Yancy’s introductory essay.

One thing I noticed about the series was its emphasis on right now. That was probably its brief, but I think it could also be worthwhile to adjust our focus, to better look at things from a distance.

Such distance might lead us to question the generalization of “times like these.” There are indeed horrible things happening, and Yancy’s references to Gaza, racism, and climate change are just a few of many well known examples. Some of these terrible things we may come to through personal experience, some mainly via ever-present news and social media, so it’s no surprise that they dominate our consciousness. Yet at any given time, countless things, good and bad, are happening. And if we take the long view (50 years? 100 years? 500 years?) we can see that in certain respects and for certain populations, “times like these” are preferable in comparison (e.g., standards of living, racism, sexism, medicine, access to information, etc.). Of course, “preferable in comparison” doesn’t mean “problem free.” It doesn’t even mean “not terrible.” But it complicates the picture somewhat.

One of the ways we’re better off—and this is building on what Elizabeth Brake says in her essay—is that we have concepts, ideas, and norms in sufficient circulation for us to better identify and understand our problems. So, in one way, things seeming worse may be a function of us having better conceptual tools by which to diagnose our situation.

Here’s what Brake says:

Too often, when pressed to defend the discipline, professional philosophers focus on philosophy’s use as a tool for rigorous argumentation and clear conceptual analysis. The idea here is that philosophy teaches the skills we need for reasoned disagreement with our fellow citizens, to avoid talking past one another and to take others’ perspectives seriously. But I find that this downplays the fact that philosophy does, and has always done, more than teach us how to argue: it generates new concepts, new tools and devices for understanding the world—and for reshaping it.

Of course, the skills of argument and critical thinking that philosophy teaches are invaluable. But these skills are valuable only so long as our fellow citizens are willing to engage in a reasonable discussion of our differences and won’t simply seek to impose their will by force. My fear is that there are times, and this might be one of them, when this condition does not obtain.

On the other hand, in the face of such things, the philosophical temptation may be quietism—the belief that the only thing to do, given our sense of powerlessness, is go inward toward the personal contemplation of Truth and Beauty, or to tend to one’s own garden. Indeed, there has lately been a resurgence in interest in the philosophy of stoicism in self-help circles.

In my view, though, both of these philosophical responses underestimate what philosophy offers: a chance to communicate with others who are interested in what we have to say and, through that communication, to initiate change. Philosophy is a powerful tool for creating and recrafting concepts that reflect our experiences and what we take to be normatively important about them; it is also a powerful tool for interrogating the ideals that guide us and asking whether we, personally and socially, really live up to those ideals. In this, philosophy offers us no less than a chance to remake the world—a possibility for creative conceptual engineering that can articulate what we previously could not and suggest alternate practices that better reflect our ideals.

Yet philosophy takes time. Not just for its production and for the filtering of worthwhile ideas, but also for ideas to get carried from academia into broader society. And it takes more time still for them to come to be a part of the predominant attitudes and beliefs in a society, the ideas people think with, such that they can play a role in efforts to “remake the world”.

So in considering the value of philosophy in “times like these,” a portion of our attention should be not on what philosophers should do now, but on what philosophers have already done that provide us with the epistemic, conceptual, and normative tools by which we make sense of these times and what we should do in them. Such an accounting may take us decades, centuries, or even millennia into the past, and show us that more of philosophy is more valuable today than many might think.

The post Philosophy’s Importance in “Times Like These” first appeared on Daily Nous.

How Deathcore Superstars Lorna Shore Evoke “the Nothing”

As the music begins to swell, colored lights slowly brighten and rise from the floor. The crowd ritually raises their hands in the shape of devil horns as anticipation builds and Lorna Shore, the deathcore band they’ve come to see, walks out. ...

Questioning Art in a Time of War

Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah is nominally addressed to Jewish teens in the United States who are preparing for their B’nai Mitzvahs (a gender-neutral rendering of Bat or Bar Mitzvah). It was published in an edition of 3,000 by Wendy’s Subway, an independent Brooklyn publisher, with support from Harvard University and VCU, which places the book squarely within an art-world context. What, if anything, can this politically-oriented book accomplish in an art context that direct activism in organizations like JVP cannot?...

Philosophical Uses for LLMs: Modeling Philosophers

Now that OpenAI has made it possible for members of the (paying) public to customize its large language model (LLM), ChatGPT, with special instructions, extra knowledge, and particular combinations of skills, the prospects of using it to create useful, interesting, and maybe even insightful “model philosophers” have improved.

[made with DALL-E]

(After all, what a technology ends up being able to do is not just a function of the technology itself, but, among other things, who has gotten to play with it.)

For an example of this, consider LucretiusGPT.

LucretiusGPT was created by research analyst Kelly Truelove. It’s an LLM version of Lucretius, or, as Truelove puts it, “a customized version of ChatGPT that is especially familiar with the ancient Roman poet Lucretius, his grand poem “On the Nature of Things,” and the philosophy of Epicurus presented in the 2,000-year-old work.”

In a dialogue with LucretiusGPT (it calls itself “Lucretius”), Truelove asks about “his” famous six-part poem and how it could be extended include a part on computers and artificial intelligence.

In response, LGPT presents an outline of “Book VII: The Age of Silicon and Reason.” Truelove notes: that the six-part structure of the proposed extension seems to correlate with what would be the preceding six “books” of the poem. LGPT replies:

Indeed, the proposed six-part structure for extending “De Rerum Natura” to encompass the developments of computing devices and artificial intelligence mirrors the original six-book layout of my work. Each part of this hypothetical extension aligns with the thematic progression and philosophical depth found in the original poem.

LGPT then goes on to explain the correlations for each part, noting:

In this extended structure, each part would serve to bridge the ancient Epicurean thought with modern scientific and technological advancements, maintaining the poem’s original spirit of exploring and understanding the natural world, human experience, and the implications of our advancements.

Truelove asks LGPT to write the poem, and it does. You can read it here.

The exchange afterwards was striking, I thought:

KT: Your addition deviates from “De Rerum Natura” in an interesting sense: It has a clear conclusion and even an epilogue. By contrast, “De Rerum Natura” ends abruptly.

LucretiusGPT: Indeed, you astutely observe a notable deviation in my proposed addition from the original “De Rerum Natura.” The original work is known for its abrupt ending, which has been a subject of much scholarly debate. Some suggest that the poem was unfinished at the time of my death, while others propose that the ending as it stands was intentional, reflecting the incomplete and ongoing nature of human understanding of the universe.

In contrast, the addition I proposed, which includes a conclusion and an epilogue, offers a more definitive closure. This choice was made to provide a sense of completion to the new themes introduced, particularly the advancements in computing and artificial intelligence. The epilogue serves to tie these modern concepts back to the Epicurean pursuit of understanding and tranquility, providing a reflective summary of the journey through the poem.

However, in keeping with the spirit of the original work, this closure does not imply that all questions are answered or that the exploration of nature and human understanding is complete. Instead, it acknowledges the ongoing nature of inquiry and the ever-evolving understanding of the universe, while offering a moment of contemplative closure to the specific themes discussed in the proposed addition.

It’s a bit of an improvement since last year’s attempt to talk philosophy with ChatGPT.

Check out the whole thing at TrueSciPhi, where Truelove has documented some of his explorations of this technology.

It would be interesting to see more “model philosophers” emerge. They might (eventually) be useful as tools for exploring possible extensions of their thoughts to matters they did not consider. It could be quite fascinating to see model philosophers converse with one another in ways that history, geography, language barriers, and other contingencies did not allow for. And they might make for good conversation partners for us. With an audio interface and a set of earbuds, you can wander about campus conversing with Kant.

A philosopher could create a model of themselves, too, trained on their own writings and notes, as well as empirical information related to their own work, and endowed with certain reasoning and research skills. One could then ask it: “what do I think about X?”, where X is something the philosopher hasn’t worked out a view on yet. The result of course is not a substitute for thought, but it could be useful, educational, and possibly insightful. One could feed one’s model the writings of others and ask, “what challenges, if any, does these texts pose to my views?” And so on. (Recall “Hey Sophi“.)

Are you aware of other model philosophers created with customized versions of ChatGPT? Have you created a model of yourself? Let us know.

By the way, if you’re unimpressed with the current technology, just imagine its capabilities 10 or 20 years down the road. Discussion of its uses, benefits, risks, implications, etc., welcome, as usual.

Related:

Two Cultures of Philosophy: AI Edition

Shaping the AI Revolution in Philosophy

The post Philosophical Uses for LLMs: Modeling Philosophers first appeared on Daily Nous.