MMT

Bill Gates Implicitly Endorses "Crazy Talk" MMT

On the one hand, I'm delighted that eminent self-made man William Henry Gates III has dismissed Modern Monetary Theory as "some crazy talk".

Gates worked his way up from practically nothing at Yale University (you've probably not heard of it) as the scion of a merely very wealthy family, to become an insanely wealthy entrepreneur. He did this upon realising that if you could copyright software (something legally uncertain at the time), you could then make an awful lot of money — from government-granted monopolies — over the wide use of the product of not an awful lot of work. His breakthrough insight was that one didn't have to wait for the establishment of legal precedent in order to begin exploiting it. Rather, you could do the two simultaneously. This proved to be his first and last history-changing innovation.

Since then Gates has been an unerring detector of, and proponent of, extraordinarily naff ideas destined for oblivion. The paradigmatic Gates bad idea came in 1995. The media famously dubbed 1995 "the Year of the Internet". In that year, Gates wrote a prophetic book full of naff ideas, and in passing he mused about the historical curiosity (nothing more than that) known as the Internet. It was, he thought, merely a signpost to the really significant online environment emerging, called the MicroSoft Network (MSN). Just as people were leaving proprietary, centralised online services like Compuserve and America OnLine in droves for the decentralised Internet, Gates was busily constructing his own new proprietary, centralised online service, because he knew a winning idea when he saw one.

So "crazy talk" is in effect a considerable endorsement of MMT by a man who will only begin to dimly perceive an undeniable truth after practically everybody else in the world has accepted it. First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they attack you, then Bill Gates ignores you and laughs at you, then you win.

On the other hand, the framing of MMT in this piece in the Verge is completely erroneous. It is misleading to say that MMT says (currency issuing) governments "need not worry about deficits because they can simply print their own currency" (emphasis mine). The scare word "print" here simply means "spend". A government spends its own money by issuing loose-leaf accounting records ("cash" to you and I), or by creating accounting entries on computers in the banking system. A currency issuing government must spend its own currency into the private sector before it can collect any of it back as taxes, fees, or fines. This "currency printing" is not novel, exceptional, radical, or crazy. It's a logical precondition of any sovereign monetary system.

Currency issuing governments cannot be said to spend any of the tax revenue they collect. Not one cent. When money is created, it is a financial liability for the government (an IOU, in effect), and a financial asset for the private sector. When the government collects money owing to it, it is merely cancelling out the liability against the asset (redeeming the IOU). Both the asset and the liability disappear in a puff of accounting. The government always spends newly created money. To claim that a currency issuing government normally uses "taxpayers' money", but in periods of wild abandon will resort to "printing money", is just flat-out wrong. Or worse, it is deliberate accounting fraud deployed for political purposes.

It is not that currency issuing governments can "print" money in order to spend; they cannot spend their own money any other way. As Warren Mosler says, the government neither has, nor does not have, any money. Or to put it another way, money isn't something a government has, it is something it does.

A further misrepresentation in the article is the claim that MMT proposes that governments should "manage inflation with interest rates". Not only do I not know of any major MMT scholar arguing any such thing, it would be hard to find any honest, knowledgable mainstream central banker who would endorse this position — and using interest rates to manage inflation is technically a major part of their job description!

Apologies for technobabble, but this is the short version: central banks (which implement monetary policy) can influence interest rates in the overnight market for funds required to settle the day's financial transactions between banks, and between banks and the government. This has a very, very weak, indirect, and unpredictable effect on private sector economic activity, and hence price stability. Much more direct and effective is the use of spending and taxation (fiscal policy) to ensure that there is neither too much money (inflationary) nor too little money (deflationary) for the goods available for sale in the economy as a whole, or in particular sectors of it.

The government uses money to achieve its (hopefully democratically determined) policy objectives. There is no alien thing out there called "the economy" which constrains how much money a government can create/spend or extinguish/tax. The limits on what we can achieve are the limits of our non-financial resources: raw materials, human beings, jam, etc.

As Modern Monetary Theory has hit so many radars that now even Bill Gates has heard of it, we can expect much more misrepresentation in future.

Which Keynesianism?

I posted this enormous torrent of blather on Blackboard the other day. It's mostly a restatement of stuff I've said before, but I'll repost it here for the purposes of copying and pasting in the likely case I have to restate it yet again elsewhere.

Because I've been studying economics for the last few years, rather than sticking to the curriculum and dutifully cultivating my employability, I feel obliged to chip in with a cautionary note: Almost all of the academic economists, and their policy prescriptions, which are characterised as Keynesian have nothing to do with the work of Keynes.

The post-war economic order established at Bretton Woods is conventionally understood as being Keynesian, but in fact Keynes was railroaded by the US representative Harry Dexter White, who insisted upon the system of fixed exchange rates pegged to the US dollar, with global dependency on holding US dollar reserves being greatly to America's benefit; the US gained the benefit of cheap foreign imports sold to acquire those reserves. Neither was Keynes responsible for the "Bretton Woods institutions", the World Bank and the IMF. His plan for regulating and settling international financial flows was considerably more humane than the usurious loans and standover tactics these institutions became notorious for.

Even "progressive" and "liberal" economists like Paul Krugman and Joe Stiglitz are members of the school of "New Keynesianism", a product of what Paul Samuelson called the "Neoclassical Synthesis"; taking some of the superficial trappings of Keynes' work and melding it with the earlier "neoclassical" school of economics, which Keynes actually intended to entirely overturn. Neoclassical models of the economy ignore the role of money and banking, believing that all economic transactions are ultimately barter transactions, and that money is therefore said to be "neutral", and banking is just redistribution of loanable funds, ultimately of no macroeconomic effect. Keynes wrote of this "Real-Exchange economics" (in an article unfortunately unavailable via SCU):

Now the conditions required for the "neutrality" of money, in the sense in which it is assumed in […] Marshall's Principles of Economics, are, I suspect, precisely the same as those which will insure that crises do not occur. If this is true, the Real-Exchange Economics, on which most of us have been brought up and with the conclusions of which our minds are deeply impregnated, […] is a singularly blunt weapon for dealing with the problem of Booms and Depressions. For it has assumed away the very matter under investigation.

This is the answer to Queen Elizabeth's question on how economists failed to see the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) coming; if the financial sector is macroeconomically neutral, as the neoclassicals claim, there cannot be any financial crises. However, outside the neoclassical tradition, the normal functioning of the economy, and the pathologies leading to crises, are well understood:

- The Chartalists determined that all money is credit, ultimately issued by the state. Michael Hudson recently did some exhaustive historical work on this, which David Graeber popularised in his book Debt: the First 500 Years.

- Wynne Godley showed how currency-issuing states must spend more than they tax if the private sector is to have the money necessary to spend and save.

- Irving Fisher identified the role of debt deflation in turning a rush to liquidate debt into an ongoing crisis where outstanding debts become impossible to repay.

- Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis extended Fisher's work to describe how financial crises arise from the normal workings of a capitalist economy.

- Keynes implicitly regarded the money economy as a tool for allocating real resources in pursuit of public policy objectives, a principle explicitly formulated by Abba Lerner as "functional finance". This is in opposition to the neoclassical intuition that a household is like an individual, a firm is like a household, and a government is like a firm; therefore a government must follow the principles of "sound finance" and "live within its means".

- All of the above are incorporated in the teachings of "Post-Keynesian" economics, which Keynes' biographer Robert Skidelsky considers closest to Keynes' own thinking. The sub-field of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) synthesises all of these into a single coherent framework for analysing the economies of countries which issue their own currency.

By the end of World War II, functional finance was so well established as to be almost universally understood to be common sense. The 1945 White Paper on Full Employment in Australia, prepared for John Curtin by H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, and based on the principles in Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, declared:

It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

(Emphasis mine.) As expressed by MMT, currency-issuing governments are not fiscally constrained. The only limits on public policy are real resource limits. During the last UK election campaign, Theresa May was vehemently insisting "there is no magic money tree". But in fact there is: it's called the Bank of England (we have the Reserve Bank of Australia), and Her Majesty's Treasury has an unlimited line of credit there. Whenever the government wants to spend, the Bank of England just credits the accounts of commercial banks. I was delighted when while campaigning May was confronted by a furious protester wanting to know "Where's the magic doctor tree? Where's the magic teacher tree?" The policy limits we should be worried about are real resources (including people), not money.

Nevertheless, mainstream economists and politicians believe, in some vague way, that (as Stephanie Kelton puts it) "money grows on rich people". So it's not surprising to read already on the discussion boards here that Keynesianism is all very desirable, but how will the federal government pay for it? This is a meaningless question. The government will pay for it like it pays for anything: by spending the money into existence. That's where all money comes from, net of private sector credit creation. Logically, it can't come from anywhere else. If the government were to try to achieve fiscal (or, conflating governments and firms again, "budget") surpluses over the long term by taxing more than they spend, as neoclassicals, including New Keynesians, recommend, they would merely be draining savings from the private sector for no good reason. State-issued money is an IOU, a tax credit. When the credit is redeemed it ceases to exist. The government doesn't have to tax in order to spend. It has to spend in order to tax. Think about it: where else would the first dollar ever taxed come from?

Now you might be thinking, hang on: what about the most fiscally responsible government we've ever had (Howard/Costello) and their record run of "budget" surpluses? The economy was going gangbusters! Okay, here's the fiscal balance for that period:

As with every currency-issuing sovereign state in history, deficits are the rule, not the exception. Here's what happened to private sector debt over the same period:

(Data from the Bank of International Settlements and OECD.) As soon as the government started taxing more than it spent, private sector debt took off, and subsequent fiscal deficits were insufficient to reverse the damage. Notably, at the same time household debt overtook corporate debt, as credit was used to sustain consumer demand, not to mention standards of living, rather than for investment in productive capacity. Australia "Nimbled it, and moved on", and to hell with the consequences.

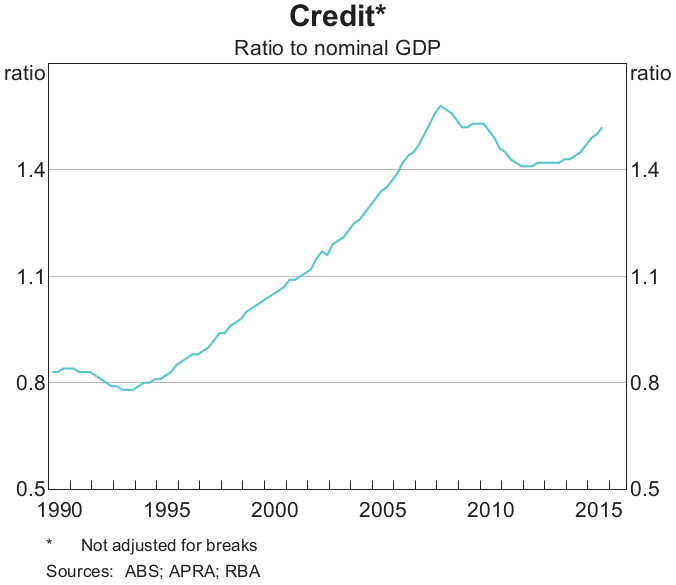

Australia recently passed two milestones of note: total private sector debt (the blue line above) exceeded 200% of GDP — at roughly the level that Japan's private debt was at in the early 90s when its real estate bubble burst — and bank equity in residential real estate passed 50%. That's 50% of the total residential real estate stock, not just houses built in the last x years. Minsky describes the path to financial collapse as progressing through the stages of "hedge finance", then "speculative finance", and finally "Ponzi finance". When you see phenomena like interest-only mortgages — where the principal is never repaid, on the assumption that housing prices only ever go up, and the debt will be settled whenever you sell the property, presumably pocketing a tidy and lightly-taxed capital gain at the same time — you know which stage you're in.

So why does nobody in mainstream politics or economics know anything about this? To put it succinctly, because neoliberalism. On the left, the "balancing the books" rhetoric serves a useful purpose: it gives you a disingenuous pretext to do what you want to do anyway that is compatible with the dominant paradigm. As Randy Wray said at a recent MMT conference:

"[Progressives] link the good policies they want to 'we'll tax the rich to pay for it'. So when you point out we don't need to tax the rich to pay for it, they're just crestfallen because they want to tax the rich. So I say 'Of course we should tax the rich. Why? They're too rich.' You don't need any other argument than that."

Taxes drive demand for the currency. If you know you have to pay taxes, you will work to get the money to pay for it. It's a coercive way for the government to mobilise labour to achieve its policy objectives, but assuming policy is arrived at democratically, it's relatively fair and vastly preferable to the autocratic alternative of having a gun put to your head. Taxes are also a fiscal instrument that can be used to discourage certain kinds of behaviour, and harmful social phenomena (like income inequality).

In the neoliberal era, that's why Australia has a retrospective tax on education called HECS-HELP, which in turn is why SCU has no school of history, or philosophy, or in fact any of the traditional academic disciplines. Students know that their education will be retrospectively taxed, so they can't afford to choose disciplines unlikely to offset that tax with increased earnings. There are twice as many universities as there were in 1988, but the new ones are glorified vocational colleges with next to no permanent academic staff. Australian post-Keynesian economist Steve Keen, who correctly predicted — and more importantly, explained — the GFC, subsequently lost his job at the University of Western Sydney when they closed down their economics department. Who needs academic economics when you have business studies courses, after all? He ended up at Kingston University in London, another young neoliberal institution, where last year he was given an ultimatum to spend more hours teaching or take a significant pay cut. He's ended up having to put his hat out for donations from the public in order to continue his work as a public intellectual.

Why would public policy function like this? Why would policy makers want a population uneducated about how the world actually works, and instead merely trained in how to work in it? Why is the conventional wisdom so full of assertions that are demonstrably untrue, and profoundly damaging to society? Paul Samuelson, author of the macroeconomics textbook that gave generations of undergraduates a completely misleading interpretation of Keynes' work explained this in an interview:

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] in every short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say "uh, oh what you have done" and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I see merit in that view.

So basically, belief in myths must be maintained among the general population wherever doing so provides support for the elite political preference for small government, i.e. for control over the economy to be exercised by private finance rather than public fiscal policy. This is what neoliberalism fundamentally is, an Orwellian fiction imposed on a deliberately dumbed-down populous, with access to the truth as much the reserve of a select educated elite as ever. "Long-run civilised life" has been restored, thanks to neoliberalism's making of the 21st century by its un-making of the 20th.

I could go on forever (evidently) but others explain all this better than I:

- Here's a short interview with Steve Keen explaining how neoliberal austerity economics leads inevitably to financial crises.

- Stephanie Kelton is probably the best person to explain MMT to a general audience. Watch her describe the Angry Birds Approach to Understanding Deficits in the Modern Economy.

- Here's Bill Mitchell explaining in 15 minutes how fiscal policy works in the real world.

- Warren Mosler explains here why fiscal deficits are generally desirable. If you find reading easier than listening, I recommend Warren's slim volume (and even slimmer PDF file) Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy.

If you have read this far, I admire your tenacity.

'Straya: Basically, she's rooted mate

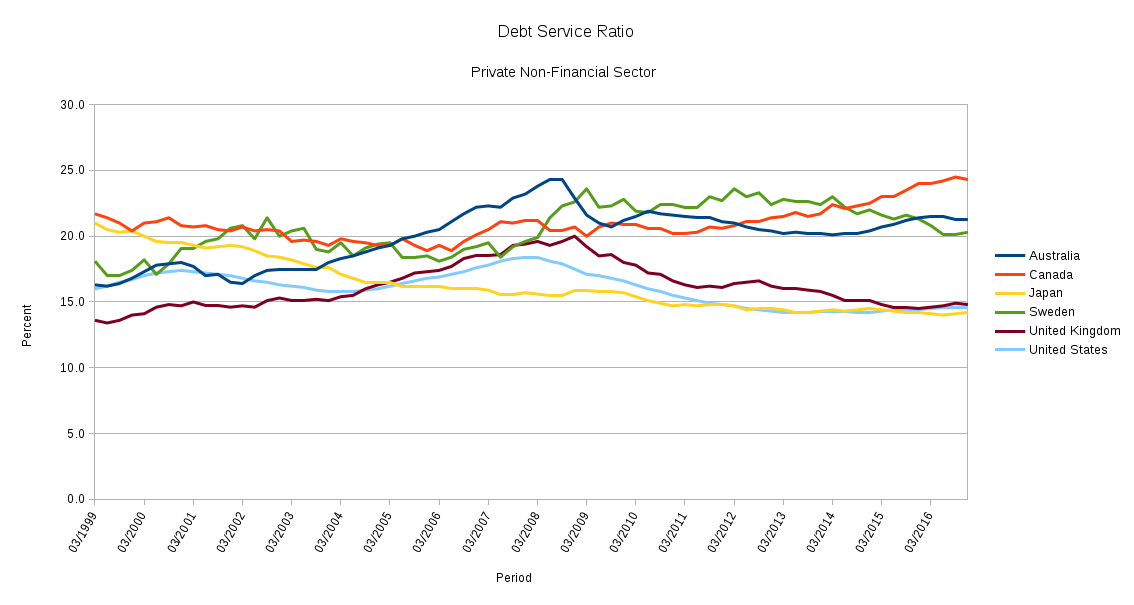

Charts! Nobody asked for them, but I have them anyway! Over the last few years the Bank for International Settlements have been publishing a fab set of statistics that are not usually brought to bear in the tea leaf reading of mainstream economists. This is a shame, as they are exactly the sort of statistics which would indicate the risk of imminent financial crisis. Last month the BIS updated the data to the end of (calendar year) 2016. Here's an illustration (courtesy of LibreOffice) of where Australia is, relative to some comparable and/or interesting countries (click to embiggen):

As the BIS explains, the Debt Service Ratio (DSR):

"reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises. Furthermore, a high DSR has a strong negative impact on consumption and investment."

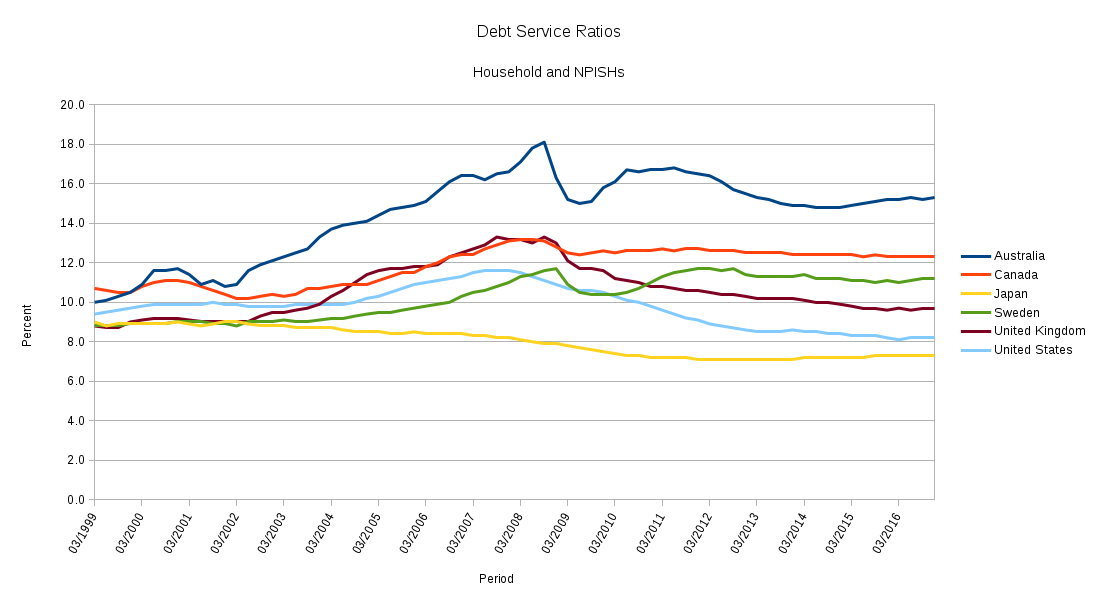

So as a measure of Australia's ability to pay at least the interest on our private sector debts, if not pay down the principal, you might think this is not a bad result. We clearly substantially delevered after the GFC, thanks in large part to the Rudd stimulus pouring public money into the private sector, then levered up a bit since, but we've ended up between Canada and Sweden, which is a pretty congenial neighbourhood. But this is total private sector debt; what happens when we take business out of the equation and just look at households (and non-profit institutions serving households - NPISHs)?

Woah! Suddenly we're in a league of our own. Canada's flatlined here since the GFC, meaning the subsequent increase in their total private debt burden has largely come from investment in business capital. In such a case, provided this investment is directed at increasing productive capacity, and is accompanied by public sector spending to proportionally increase demand, this is sustainable debt. Australia has been doing the opposite.

Here's another way of looking at the coming Australian debt crisis, private sector credit to GDP:

This ratio will rise whether the level of debt rises, GDP falls, or both, so it's another good indicator of unsustainable debt levels. The current total level (in blue) of over 200% is at about the ratio Japan was at when its real estate bubble burst in the early 1990s. Breaking this down again into household and corporate sectors, we see that over the mid-1990s Australia switched the majority of its private sector borrowing from business investment to sustaining households. What happened in the mid-90s? Data here from the OECD:

From the mid-1990s to 2007 Australia experienced the celebrated run of Howard/Costello government fiscal (or "budget") surpluses. We all know, or should know, thanks to Godley's sectoral balances framework, what happens when the public sector runs a surplus: the private sector must run a corresponding deficit, equal to the last penny. There is nowhere else, net of private sector bank credit creation (which zeroes out because every financial asset created in the private sector has a corresponding private sector liability), for money to come from. When the government taxes more than it spends, it is withdrawing money from the private sector. Mainstream economics calls this "sustainable", and "sound finance", meaning of course it is nothing of the sort.

How did the private sector, and the household sector in particular, continue to spend from that point onward, behaving as though losing money (not to mention public infrastructure and services) down the fiscal plughole was not merely benign but quite wonderful? It chose to Nimble it and move on, going on a massive credit binge. The banks were happy to provide all the credit demanded, because the bulk of the lending was ulitimately secured by residential real estate prices, and these were clearly going to keep rising without limit (thank heavens, because if they were to fall like they did in the US in 2007…).

The Global Financial Crisis put a dent in the demand for credit, but as subsequent government fiscal policy has tightened, under the rubric of "budget repair", it is rising again. We are already in a state of debt deflation: Australia's household debt service ratio (as above), at between 15 and 20 percent of household income for over a decade, has dampened domestic demand, leading to rising unemployment and underemployment, leading to more easy credit as a quick fix for income shortfalls ("debtfare"). More of what income remains is redirected to debt servicing rather than consumption, and so we spiral downwards, our incomes purchasing less and less with each turn. [I will post more about some of the social and microeconomic consequences in (over-)due course.]

The Australian government needs to spend much, much more - and quickly. Modern Monetary Theory, drawing on an understanding of the nature of money that goes back a century, shows us that government spending (contrary to conventional wisdom) is not revenue-constrained; a currency-issuing government can always buy anything available for sale in the currency it issues. There is nothing about our collective "budget" that needs repairing before we can do so. The same data from the OECD shows that most currency-issuing governments with advanced industrial economies run fiscal deficits almost all the time:

In fact, under all but exceptional conditions, government fiscal surpluses (i.e. private sector fiscal deficits) are a recipe for recession or depression. The greater the surplus, the greater the subsequent government spending required to lift the private sector out of crisis, as can be seen above in the wild swings in neoliberal governments' fiscal position from the mid-90s on. The fiscal balance over any given period is nothing more than a measurement of the flow of public investment into the private sector. What guarantees meaningful sustainability is a government's effective use of functional finance to manage the real (as opposed to financial) economy in pursuit of public policy objectives. Refusing to mobilise idle resources (including, crucially, labour) for needed public goods and services is not "sound finance"; it is the very definition of economic mismanagement, as was once widely recognised:

"It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

"In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

"Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

"The policy outlined in this paper is that governments should accept the responsibility for stimulating spending on goods and services to the extent necessary to sustain full employment. To prevent the waste of resources which results from [un]employment is the first and greatest step to higher living standards."

We chose to forget all this from the 1980s onward. We can choose to remember it at any time.

Wednesday, 15 February 2017 - 5:22pm

I'm ranting altogether too much over local "journalism", and this comment introduces nothing new to what I've posted many times before, but since the Advocate won't publish it:

Again I have to wonder why drivel produced by the seething hive mind of News Corp is being syndicated by my local newspaper. This opinion comes from somebody who appears to be innumerate (eight taxpayers out of ten doesn't necessarily - or even very likely - equal eight dollars out of every ten) economically illiterate, and empirically wrong.

Tax dollars do not fund welfare, or any other function of the federal government. Currency issuing governments create money when they spend and destroy money when they tax. "Will there be enough money?" is a nonsensical question when applied to the federal government. As Warren Mosler puts it, the government neither has nor does not have money. If you work for a living, it is in your interest that the government provides money for those who otherwise wouldn't have any, because they spend it - and quickly. Income support for the unemployed becomes income for the employed pretty much instantly. Cutting back on welfare payments means cutting back on business revenues.

And the claim that the "problem" of welfare is increasing in scale is just wrong. Last year's Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) report shows dependence on welfare payments by people of working age declining pretty consistently since the turn of the century. This opinion piece is pure class war propaganda. None of us can conceivably benefit in any way from pushing people into destitution in the moralistic belief that they must somehow deserve it.

The Joy of Economic Irresponsibility: or how I learned to stop worrying and love the public debt

If there's one thing I've learned in the last year that I think is so important it's worth shouting from the rooftops, it's that simultaneously studying economics and the psychology of stress while also being personally stressed about money is a very, very bad idea.

If there are two important things I've learned in the last year, I'd say that the more generally applicable one to the citizen in the street is that a government which issues it's own money can never run out of it.

Such a government can of course pretend, or at least behave like, it can run out of money. In fact, many have done so for the last thirty years or so, and the results have been disastrous. You don't have to take my word for it. Here are some graphs, mostly from the RBA Chart Pack, except where otherwise indicated. Here's the Australian government fiscal balance, misleadingly labelled "budget balance" as per the conventional misunderstanding of reality.

Things took a dip from 2007/8, but deficits are improving, and we were in surplus for most of the preceeding decade. And that's good, isn't it? Surpluses mean we have more money, don't they?

Generally, yes. A "budget surplus" for a business or household means more money at hand to spend later. However, for an economy with a sovereign-currency-issuing government, public fiscal surpluses mean we have less money.

How is this possible? To understand this, you have to understand that accountancy—specifically double-entry bookkeeping and balance sheets—is the foundation of economics; at least economics of a realistic kind. All money is credit money. You make money—literally—by being in debt to somebody, and by denominating this debt in the country's transferrable unit of account. Spending is the simultaneous creation of a debt on the buyer's side of the ledger, and a corresponding credit on the seller's side. However, if you happen to hold enough credits that have already been generated as the flipside of a debt in your favour, you can use these credits to immediately cancel the debt of the current transaction. One way most of us do this on a daily basis is by using cash. Cash is a transferrable token of public sector debt and private sector credit.

Three percent of the immediately-spendable money in the private sector is in the form of cash. The other 97% is just numbers stored on computers in the commercial banking sector. Most of this is money that originated as commercial bank loans, and will disappear from the bank's balance sheets as those loans are repaid (though of course in the meantime more loans will have been made). However, a significant amount of money originates as loans the government makes to itself (technically the central bank lends to the treasury), eventually ending up in the private sector as cash, or (through a mindbending process I will mercifully omit from this account) as commercial bank deposits. A currency-issuing government can always lend more money to itself in order to spend, and never has to pay it back. It follows that such a government does not need to tax in order to spend, and only ever taxes for other reasons. Economics textbooks, and economic commentators, routinely get this utterly and comprehensively wrong. Consider this textbook description of economic "automatic stabilisers":

"During recessions, tax revenues fall and welfare payments increase thereby creating a budget deficit. In times of economic boom, tax revenues rise and welfare payments fall creating a budget surplus."

Budget deficits are not an eventual consequence of government spending; the spending and the creation of a debt are the same operation. Tax revenues merely redeem a part of the already-accrued debt; the money issued by public spending is a public IOU that effectively disappears when private parties use it settle their tax debt owed to the public. Tax revenues therefore cannot be used to fund public spending; in order to spend, new public debt must be issued. The automatic stabilisers are real (assuming a somewhat sensible tax system), but the important part of their function is on the private side: injecting new money to stimulate demand when needed, or putting the brakes on dangerous speculative activity in a boom. The government's fiscal position from one year to the next is an inconsequential side-effect.

Taxation is the elimination of money, and hence of the demand for goods, services, and assets that drives the private sector economy. Don't believe me? Lets take a wider focus on the fiscal balance numbers above:

[Source]

Generally, and especially prior to the neoliberal period, public fiscal surpluses are the exception, not the rule. And for a good reason; it's generally not a good idea to drain demand out of the economy. So what happens when you toss good sense aside, and insist on surpluses for their own sake? Here's what happened to public sector debt:

I'm presuming (the ABS Chart Pack doesn't specify) that this is debt owed to private sector banks in the form of loans and government securities. I should stress that, as with taxation, these operations are not required to finance spending, and are only ever done for other reasons (such as hitting interest rate targets). Also, because they don't issue currency themselves (though this is possible, and has worked elsewhere), lower levels of government do have to rely in part on revenue-raising to fund spending, though grants from the federal government also play a big part in determining their fiscal position.

Still—phew!—we got that scary public sector debt under control until the GFC, and we can do it again! But hang on, if that's taking money out of the private sector, where does the private sector get the money to sustain demand? Here's the private sector debt over the same period:

Note that this is one and a half times GDP, compared to the one third of GDP outstanding to the public sector, at the height of its alleged fiscal irresponsibility. When government self-imposes limits on its ability to spend, private sector credit creation takes up the slack. Who do you want controlling how much money is created, who gets it, and what it gets spent on? A mix of the commercial finance sector and a (somewhat) democratically-accountable government? Or just the bankers?

Most of private-sector money creation is commercial bank loans, and as economist Michael Hudson notes, in the US, UK, and Australia, 70 percent of bank loans are mortgages. That's a hell of a lot of money (what's 70 percent of one and a half times GDP?) dependant for its existence on the soundness of pricing for a single class of asset. If real estate prices suddenly crash, and mortgagees start to default on their loans, poof! The corresponding credits on the other side of the ledger are gone too, and the real estate sector takes the whole economy down with it. You can't argue with balance sheets.

Still, I expect we'll be fine as long as we stay the fiscal responsibility course, and don't let the government "spend more than it earns". Real estate prices only ever go up, don't they? And it's not like bankers would ever be led by their own short-term interests to make a huge amount of risky loans and inflate an enormous real estate price bubble…

Thursday, 11 February 2016 - 1:39pm

I'm reluctant to contribute to the Piketty backlash, as it seems to me to be mostly motivated by the unrealistic expectation that his book should have provided a comprehensive theory of everything. However this blog post from Alexander Douglas provides such a pithy account of the workings of public fiscal balances that it's worth recirculating. In response to the claim that "there are two main ways for a government to finance its expenses: taxes and debt," he writes:

Government spending isn’t financed by anything. The government pays for everything by crediting the non-government sector (employees, companies, foreign governments, etc.) with financial claims. Some of these claims are returned to the government in order to settle liabilities to the government (for instance in tax payments); others remain as financial holdings for the non-government sector. At any given moment the claims remaining as financial holdings constitute the whole of the ‘public debt’.

Tax revenue largely depends on the volume of spending. Decisions to spend rather than save are largely at the discretion of non-government agents. It is therefore very misleading to speak, as Piketty does, as if the government chooses to ‘finance its spending’ through taxation or debt. The amount of government spending that remains as ‘debt’ is largely up to the discretion of non-government agents choosing whether to hold onto financial claims or pass them on so that they can eventually find their way back to the government.

It therefore makes no sense to panic about government "budget" deficits, if you're not also going to bemoan private savings. Ironically, as it happens, private savings currently is a big problem, as corporations hand out mattress stuffing — in the form of dividends and share buybacks — rather than investing. Yet more ironically, the appropriate response is for the government to make up the investment shortfall through large fiscal deficits. Otherwise the economic stagnation rolls on until (sorry, I can't resist it) r>g.

Deficit, Deficit, Who's got the Deficit? (Secular stagnation edition)

Over 50 years ago, James Tobin wrote an article for the New Republic entitled "Deficit, Deficit, Who's got the Deficit" (1963) that explains why the US federal government almost always needs to run a budget deficit.

The article is a gem. It has everything a good macroeconomics article should have: lots of debunking, all the relevant data, and a good dose of policy recommendations.

Unfortunately, the article is nowhere to be found on the internet. This post seeks to fix that by providing some key excerpts. Another purpose of this post is to use Tobin's analytical framework in that article and apply it to today's economic environment in the US.

Tobin on US Sectoral Financial Balances, circa 1963

The article starts off by describing the fundamental (iron?) law of financial balances:

For every buyer there must be a seller, and for every lender a borrower. One man's expenditure is another's receipt. My debts are your assets, my deficits your surplus.

If each of us was consistently "neither borrower nor lender," as Polonius advised, no one would ever need to violate the revered wisdom of Mr. Micawber. But if the prudent among us insist on running and lending surpluses, some of the rest of us are willy-nilly going to borrow to finance budget deficits.

In the United States today one budget that is usually left holding a deficit is that of the federal government. When no one else borrows the surpluses of the thrifty, the Treasury ends up doing so. Since the role of debtor and borrower is thought to be particularly unbecoming to the federal government , the nation feels frustated and guilty.

Unhappily, crucial decisions of economic policy too often reflect blind reactions to these feelings. The truisms that borrowing is the counterpart of lending and deficits the counterpart of surpluses are overlooked in popular and Congressional discussions of government budgets and taxes. Both guilt feelings and policy are based serious misunderstanding of the origin of federal budget and surpluses. (1963:10)

Tobin then goes on to explain that both the household and financial sectors were running large financial surpluses (worth $20 billion combined in 1963):

American households and financial institutions consistently run financial surpluses. They have money to lend, beyond their own needs to borrow. As a group American households and non-profit institutions have in recent years shown a net financial surplus averaging about $15 billion a year -- that is, households are ready to lend, or to put into equity investments...more than they are ready to borrow. [...] In addition, financial institutions regularly generate a lendable surplus, now of the order of $5 billion a year. For the most part these institutions -- banks, saving and loans associations, insurance companies, pension funds, and like -- are simply intermediaries which borrow and relend the public's money. Their surpluses result from the fact that they earn more their lending operations than they distribute or credit to their depositors, shareowners, and policyholders. [...]

The article goes on to list the sectors of the economy that must borrow the $20 billion in surplus funds available from households and financial institutions:

State and local governments as a group have been averaging $3-4 billion a year of net borrowing...Unincorporated businesses, including farms, absorb another 3-4 billion a year. To the rest of the world we can lend perhaps $2 billion a year. We cannot lend abroad -- net -- more than the surplus of our exports over our imports of goods and services, and some of that surplus we give away in foreign aid. [...]

The remainder -- some $10-12 billion -- must be used either by nonfinancial corporate business or by the federal government. Only if corporations as a group take $10-12 billion of external funds, by borrowing or issuing new equities, can the federal government expect to break even. [...]

Tobin then follows into a discussion about the policy implications of these lending and borrowing dynamics:

The moral is inescapable, if startling. If you would like the federal deficit to be smaller, the deficits of business must be bigger. Would you like the federal government to run a surplus and reduce its debt? Then the business deficits must be big enough to absorb that surplus as well as the funds available from households and financial institutions.

That does not mean business must run at a loss -- quite the contrary. Sometimes, it is true, unprofitable business are forced to borrow or to spend financial reserves just to stay afloat; this was a major reason for business deficits in the depths of the Great Depression. But normally it is business with good profits and good prospects that borrow and sell new shares of stock, in order to finance expansion and modernization...The incurring of financial deficits by business firms -- or by households and governments for that matter -- does not usually mean that such institutions are living beyond their means and consuming their capital. Financial deficits are typically the means of accumulating nonfinancial assets -- real property in the form of inventories, buildings and equipment.

When does business run big deficits? When do corporations draw heavily on the capital markets? The record is clear: when business is very good, when sales are pressing hard on capacity, when businessmen see further expansion ahead. Though corporations' internal funds -- depreciation allowances and plowed-back profits -- are large during boom times, their investment programs are even larger. [...]

Recession, idle capacity, unemployment, economic slack -- these are the enemies of the balanced government budget. When the economy is faltering, households have more surpluses available to lend, and business firms are less inclined to borrow them. (1963:11)

The Corporate Sector: From Deficits to Large Surpluses

Of course, at the time Tobin wrote this article, US financial balances weren't exactly the same as they are today. Households as a group were running financial surpluses, the US was mostly a net lendor to the rest of the world, and the corporate sector was a net borrower of funds. Essentially, three things have changed since the mid-1980s with respect to financial balances (see charts below, double-click to enlarge).

First, starting in the mid-1980s, the US has become a net borrower to the rest of the world. Second, since the early 1990s and until the financial crisis, households were net borrowers to other sectors; since 2007, the household sector has returned to its traditional role of being a net lender. Finally, since the 1990s, the corporate sector has been at different times either a net lender or net borrower. However, since 2009, the corporate sector has been running a very large net financial surplus.*

What is the main policy implication to take-away from this state of affairs?

I would venture that the main take-away is that it's unlikely the US federal government will balance its budget any time soon unless households and/or firms start spending again.

In a recent article for an IMF publication entitled "Secular Stagnation: Affluent Economies Stuck in Neutral", economist Robert Solow (MIT) discussed the business sector's net lending position as a possible sign that there may be a "shortage of investment opportunities yielding a rate of return acceptable to investors" or, stated differently, that the "real rate of interest compatible with full utilization is negative, and not consistently achievable", a situation associated with the notion of "secular stagnation":

In the United States, at least, business investment has recovered only partially from the recession, although corporate profits have been very strong. The result, as pointed out in an unpublished paper by Brookings Institution Senior Fellows Martin Baily and Barry Bosworth, is that business saving has exceeded business investment since 2009. The corporate sector, normally a net borrower, became a net lender to the rest of the economy. This does smell rather like a reaction to an expected fall in the rate of return on investment, as the stagnation hypothesis suggests. (see chart below)

Source: Baily and Bosworth, 2013

Secular Stagnation

So what can be done? Paul Samuelson and Anthony Scott asked a similar question in the 1971 Canadian edition of their Economics textbook:

What if our continental economy is in for what Harvard's Alvin Hansen called "secular stagnation"? - which means a long period in which slowing population increase, [...], high corporate saving, the vast piling up of capital goods, and a bias toward capital-saving inventions will imply depressed investment schedules relative to saving schedules? Will not active fiscal policy designed to wipe out such deflationary gaps then result in running a deficit most of the time, leading to a secular growth in the public debt? The modern answer is "Under these conditions, yes; and over the decades the budget should not necessarily be balanced." (1971:436-7)

In my next post, I'll write more about secular stagnation and policy responses to address its possible eventuality.

* This post by Brian Romanchuk contains many useful charts and information on financial balances, as well as discusses secular stagnation from a stock-flow consistent perspective.

Update: I added charts on 2014-10-14, following a comment by Ramanan.

References

Baily, M. N., B. Bosworth, "The United States Economy: Why such a weak recovery", September 11, 2013, Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Samuelson and Scott, Economics, 3rd Canadian Edition, McGraw-Hill, 1971

Solow, R., "Secular Stagnation: Affluent Economies Stuck in Neutral", in Looming Ahead, Finance and Development, vol. 51 , no.3. September 2014.

Tobin, J., "Deficit, Deficit, Who's got the Deficit?", New Republic, January 19, 1963

When the Fed supported a Job Guarantee policy (and the economist who made it happen)

Circuit here. I'm back from a few months hiatus following the birth of my second child, a baby girl. Thanks to all readers for your continued interest in this blog.

A few weeks ago, Rolling Stone magazine ran a piece by Jesse Myerson supporting the idea that the government should guarantee a job to anyone who is willing to work. In their recent work, Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein also give support to this policy proposal. Randy Wray, Warren Mosler and other modern money (MMT) economists have been pushing for this idea for a long time. On the center-right and right, the idea is being promoted by Peter Cove and Kevin Hasset.

This is good news. I certainly welcome a good debate on this idea. That said, it's too bad that commentators who are skeptical of the idea simply dismiss it as a non-starter for policymakers.

This, of course, is overstating the case somewhat. It's worth recalling that in the 1970s none other than the Chairman of the Federal Reserve supported the idea that the federal government should be the "employer of last resort". Here's the former Fed Chairman Arthur Burns back in 1975:

I believe that the ultimate objective of labor market policies should be to eliminate all involuntary unemployment. This is not a radical or impractical goal. It rests on the simple but often neglected fact that work is far better than the dole, both for the jobless individual and for the nation. A wise government will always strive to create an environment that is conducive to high employment in the private sector. Nevertheless, there may be no way to reach the goal of full employment short of making the government an employer of last resort. This could be done by offering public employment -- for example, in hospitals, schools, public parks, or the like -- to anyone who is willing to work at a rate of pay somewhat below the Federal minimum wage.

With proper administration, these public service workers would be engaged in productive labor, not leaf-raking or other make-work. To be sure, such a program would not reach those who are voluntarily unemployed, but there is also no compelling reason why it should do so. What it would do is to make jobs available for those who need to earn some money.

It is highly important, of course, that such a program should not become a vehicle for expanding public jobs at the expense of private industry. Those employed at the special public jobs will need to be encouraged to seek more remunerative and more attractive work. This could be accomplished by building into the program certain safeguards -- perhaps through a Constitutional amendment -- that would limit upward adjustment in the rate of pay for these special public jobs. With such safeguards, the budgetary cost of eliminating unemployment need not be burdensome. I say this, first, because the number of individuals accepting the public service jobs would be much smaller than the number now counted as unemployed; second, because the availability of public jobs would permit sharp reduction in the scope of unemployment insurance and other governmental programs to alleviate income loss. To permit active searching for a regular job, however, unemployment insurance for a brief period -- perhaps 13 weeks or so -- would still serve a useful function.

The idea was even supported by one of the most respected names in economics at the time: Franco Modigliani. When asked to comment on Chairman Burns's proposal during a testimony before the Congressional Banking committee in 1976, Modigliani said the following:

...the idea of a public employment program as an employer of last resort, which is an alternative to unemployment compensation, strikes me as a very sound idea (p. 110).

Interestingly, the economist who got Burns and the Fed to put serious thought into the idea of a job guarantee was another well-respected contributor to US public policy during that period: Eli Ginzberg.

Job Creation through Public Service Employment

Eli Ginzberg was a Professor of Economics at Columbia University and author of numerous books on human resources and manpower economics. He was also -- in the language of Harold Wilensky and organizational sociology -- a "contact man", a person who provides ideas and furnishes intelligence to decision-makers on the political and ideological tendencies in the society at large. Ginzberg played this role throughout his career as presidential adviser for many administrations and through his affiliation with the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation (MDRC), which recently marked its 40th year of operation.

Ginzberg was an institutional economist in the tradition of John M. Clark and Wesley C. Mitchell who believed fervently that "people, rather than physical or financial capital, were the principal source of productivity and wealth" (1987:107). For this reason, Ginzberg believed it was critical for the government to eliminate unemployment as quickly as possible through the use of a publicly-funded jobs program.

Another reason why Ginzberg believed the government ought to be employer of last resort is that he understood that economies sometimes face a shortfall in jobs that makes it impossible for all unemployed workers to find work:

Just as reality has mocked the ethos of equality of opportunity for many minority children, the counterpart doctrine that adults are responsible for their own support and that of their dependents has been undermined by the continuing shortfall in jobs. The existence of high unemployment rates make it socially callous, even reprehensible, for a society to continue to affirm the doctrine that all adults who need income should work and then not provide adequate opportunities for many of them to fulfill this imperative.

Although the US experimented with federally financed job creation in the 1930s and again in the 1970s, the record in retrospect must be viewed as equivocal. Most students believe that on balance the New Deal was right to put large numbers of the unemployed to work on governmentally financed programs rather than to keep them on the dole as the British did. (1987:162)

On this last point concerning whether income transfers or guaranteed work should be the centerpiece of US social policy, Ginzberg's view was informed by the work he did during the Great Depression. Here's how Ginzberg summarized the conclusions of a 1947 book entitled The Unemployed that he co-authored on the topic of unemployment during the Great Depression:

The principal lessons I extracted included the superiority of work relief over cash support...; the cause of unemployment being rooted in a shortfall in demand for labor, not in the inadequacies of the unemployed; the centrality of work and self-support for the integrity of the individual worker, his family, and the community. By the time our investigation was concluded, [we] were convinced that no society concerned about its security and survival could afford to remain passive and inert in the face of long-term unemployment. We argued that in the absence of an adequate number of private sector jobs, it was the responsibility of government to create public sector jobs. (1987:111)

Ginzberg also believed that guaranteed work for those who are able and willing would find greater acceptability among Americans than a policy that would require government providing a guarantee income to everyone. According to Ginzberg, providing guaranteed income to everyone would conflict with the powerful American ethos of self-reliance and the American population's highly favorable view toward the culture of work:

There is no simple way, in fact, there is no way to square the following: to provide a decent minimum income for every needy person/family in the US, given the differentials in living standards, public attitudes, and state taxing capacity, and at the same time avoid serious distortions in basic value and incentive systems that expect people to be self-supporting through income earned from paid employment. (157)

For this reason, Ginzberg believed that a job guarantee should play a key role in social policy:

Accordingly, I would like to shift the focus from welfare to work, from income transfers to the opportunity to compete, from dependency status to participation in society. In advocating this shift toward jobs and earned income and away from unemployment and income transfers, the planners must focus on two fundamentals: the developmental experiences that young people need in order to be prepared to enter and succeed in the world of work; and the level of employment opportunities that a society must provide so that everybody able and willing to work, at least at the minimum wage, will be able to do so. (157)

In the 1970s, Ginzberg held the position of Chairman of the National Commission for Manpower Policy, a government-mandated commission that produced some of the best policy-oriented research on the topic of public service employment, including an excellent paper entitled "Public Service Employment as Macroeconomic Policy" by Martin Neil Baily and Robert Solow (1978) that explains how public service employment (PSE), while not necessarily more stimulative than the normal kind of fiscal policy (e.g., government spending on goods and services and tax measures), can be a perfectly sensible policy if the program is well-administered and the jobs that are created provide useful social output:

We conclude that the main advantages of PSE over conventional fiscal policy are: (a) that it can be targeted to provide jobs for hard-to-employ groups in the labour force, and for especially depressed cities and regions; (b) that PSE employment, correctly targeted, may be slightly less inflationary than the same amount of ordinary private sector employment, so that total employment can safely be a little higher with a PSE component; and (c) that PSE can be coordinated with other forms of social insurance -- public assistance and unemployment insurance, for instance -- to make them perhaps more effective and certainly more acceptable to public opinion. (1978:30)

Solow later revisited the issue of public service employment in Work and Welfare (1998), in which he argued that any attempt to reform the welfare system in order to get the unemployed back to work would only succeed if every able and willing worker is given access to a job through public service employment and/or by offering incentives to businesses to hire the unemployed.

The Deal

It was in the 1970s that Ginzberg persuaded Chairman Burns to call on the US federal government to become the employer of last resort. Here's Ginzberg's account of how he was able to get the Fed Chairman to support the job guarantee:

I made a deal with Arthur Burns when he was the head of the Federal Reserve, that I would try to control the amount of money we asked for from the Congress for manpower training if he would come out in favor of the government as the employer of last resort. And he did it. It took him a year, but I negotiated with him and he did it.

A final word. Although Ginzberg supported the idea of a job guarantee, he fully recognized the high budgetary cost that such a policy would entail and the practical challenges facing public administrators in terms of successfully implementing a public service employment program. To address these concerns, he believed the government authorities should make improvements to the program using trial and error and cautious experimentation. But the key, he would argue, is to ensure that the jobs created through these measures provide productive social output:

There is no big trick to put more and more people on public service employment. If that is the only thing that one is interested in, obviously, the Federal Government can create the money by fiat and put more people on public service employment. The question is what are the short- and long-run implications of doing that in terms of keeping our economy productive, competitive and innovative....So I do not think it is just jobs; it is productive jobs and that is another way of saying that the Federal Government can go only part of the way in terms of assuring that we have a productive economy.

References

Baily, Martin N. and Robert Solow, "Public Service Employment as Macroeconomic Policy", National Commission for Manpower Policy, 1978

Ginzberg, Eli, The Skeptical Economist, Boulder and London: Westview Press, 1987

National Commission for Manpower Policy, "Job Creation through Public Service Employment: An Interim Report to the Congress", 1978

Solow, Robert, Work and Welfare, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998

On the (ir)relevance of the money multiplier model: The Fed view

It has long been known within the Federal Reserve System -- especially among economists who worked in the FRS in the 1970s and 1980s when much of the research agenda was directed at issues of monetary control -- that the money multiplier model of money stock determination is not the most realistic (or useful) way to understand how central banks conduct monetary policy.

Here is the former Fed Governor, the late Sherman Maisel, during a conference on the theme of 'Controlling Monetary Aggregates' in 1971:

It is clear that, as a matter of fact, the Federal Reserve does not attempt to increase the money supply by a given amount in any period by furnishing a fixed amount of reserves on the assumption that they would be multiplied to result in a given increase in money [...]

Many unsophisticated comments and theories speak as if the Federal Reserve purchases a given quantity of securities, thereby creating a fixed amount of reserves, which through a multiplier determines a particular expansion in the money supply. Much of modern monetary literature is actually spent trying to dispel this naive elementary textbook view which leads people to talk as if (and perhaps to believe) the central bank determines the money supply exactly or even closely--in the short run-through its open market operations or reserve ratio. This incorrect view, however, seems hard to dislodge. (1971:153, 161)

Briefly, the money multiplier is basically a relationship between deposits (D) and reserves (R), D = mR, (or M = mB) where m is called the money multiplier (or M is money stock and B is the monetary base). According to the model, if banks keep excess reserves to a minimum and reserve requirements are applied to all deposits, then the multiplier can be constant and the central bank -- if it retains control of the volume of reserves -- can control the amount of deposits (Goodfriend and Hargraves, 1983:5). However, if the central bank does not exercise control over the amount of reserves, the multiplier model is inoperable and cannot be exploited for monetary control purposes.

The Classic Fed View

In the US, the Fed's inability to control the quantity of reserves in recent decades (before October 2008) is said to be because of the introduction of lagged reserve requirements in the late 1960s and the Fed's almost continuous use of an interest rate operating procedure.

Former St. Louis Fed economist, R. Alton Gilbert, discussed the impact of lagged reserve accounting on Fed operations in his article "Lagged Reserve Requirements: Implications for Monetary Control and Bank Reserve Management" (1980):

[Lagged reserve accounting] breaks the link between reserves available to the banking system in the current week and the amount of deposit liabilities that banks can create in the current week. If banks increase aggregate demand deposits liabilities in response to an increase in loan demand, they are under no immediate pressure to reduce their deposit liabilities...Under LRA, the Federal Reserve tends to adjust total reserves each week in response to the total deposit liabilities that banks created two weeks earlier. (1980:12)

With lagged reserve requirements in effect the volume of reserves is determined by banking system demand. Reserve demand is simply accommodated and required reserves serve only to enlarge the demand for reserves at any given level of deposits. Under LRA, the change in R occurs as a result of changes in D, the exact opposite of the money multiplier model.

Former Richmond Fed economist, Marvin Goodfriend, discussed the relevance of the money multiplier model when lagged reserve requirements are in effect in his paper "A model of money stock determination with loan demand and a banking system balance sheet constraint" (1982):

...[T]he discussion has shown that the money multiplier is not generally a complete model of money stock determination and is actually irrelevant to money stock determination for some monetary control procedures. Specifically, the money multiplier is irrelevant to determination of the monetary aggregates if lagged reserve requirements are in effect. (1982:15)

As for the other institutional factor relating to the Fed's use of an interest rate operating procedure, Robert Hetzel of the Richmond Fed highlighted the following in his paper "A Critique of Theories of Money Stock Determination" (1986):

Deposits and reserve demand are determined simultaneously with credit creation. As a consequence of defending its rate target, the monetary authority, by creating an infinitely elastic supply of reserves, accommodates whatever reserve demand emerges...In a regime of rate targeting, neither the quantity of reserves nor the desired reserves-deposits ratio of the banking system exercises a causal role in the determination of the money stock (1986:6) [...]

Interest rate smoothing by the monetary authority makes reserves and the money stock endogenous...Since [Chester] Phillips (1921), reserves-money multiplier formulas have been derived from a model of the banking sector summarized in the multiple expansion of deposits produced by an injection of reserves. The existence of markets for bank reserves, however, renders this model untenable. Phillips' model assumes that the individual bank is constrained by the quantity of its reserves and that its asset acquisition and deposit creation are driven by discrepancies between actual and desired reserves. Given the existence of markets for bank reserves, such as the fed funds and CD markets, however, individual banks are constrained by the price, rather than the quantity, of reserves they hold. (1986:20) (emphasis added)

A succinct and detailed discussion of the problems associated with multiplier models of money stock determination is found in the excellent article "Understanding the remarkable survival of multiplier models of money stock determination" (1992) by former Fed economist, Raymond Lombra:

Assuming textbook authors reveal their intellectual and pedagogical preferences and beliefs, a careful survey of the leading intermediate textbooks in money and banking and macroeconomics reveals a uniform and virtually universal consensus – the multiplier model of money stock determination is widely viewed as the most appropriate and presumably most correct approach to the topic...Since such consensus is not, in general, an enduring characteristic of monetary economics, one is tempted to “let sleeping dogs lie”. The problem is that the multiplier model, whether viewed from an analytical or empirical perspective, is at best a misleading and incomplete model and at worst a completely misspecified model. (Lombra, 1992:305) (emphasis added)

Lombra's article is especially useful because it groups together the different critiques of the multiplier approach into two categories (the article discusses a third set of critiques relating to the predictive accuracy of multiplier models but this issue is less relevant for this post).

The first set of critiques identified by Lombra is that the multiplier model "is not structural but rather is a reduced-form", a point first made in the 1960s by proponents of the "New View" (including James Tobin in "Commercial banks as creators of "money")*. Lombra summarizes this critique as follows:

Succinctly stated, the critique emphasizes that the multiplier approach abstracts from the short-run dynamics of adjustments by banks and the public, leaves the role of interest rates implicit rather than explicit, and proceeds that the movements in the monetary base (or reserves) are orthogonal to fluctuations in the multiplier. The multiplier model, it is argued, implies that deposit expansion is quantity constrained through the Fed's control over the sources of bank reserves (chiefly, the Fed portfolio of securities). One of the most forceful and articulate crafters of the critique, Basil Moore, concludes that "as a result, the money multiplier framework is of no analytical or operational use".

The consensus view of the staff and policymakers within the Federal Reserve, as revealed in numerous publications, embraces much, if not all, of the critique advanced by Moore and others. In particular, the Fed adheres to the view that the system is equilibrated through the movements of interest rates, which through their effects on bank revenues and costs, determine banks' and the public's desired asset and liability positions. In this view, money is controlled by using open market operations to affect interest rates which in turn affect demand and thus the uses of bank reserves (chiefly, required reserves). (307)

The second set of critiques discussed by Lombra concerns the issue of the endogeneity of reserves, that is, the notion that the quantity of reserves is in practice determined by the banking system:

This contention, which is related to the lagged reserve accounting scheme...and the Fed's interest rate operating procedure in effect for virtually all of the post-Accord period, implies the multiplier model is completely irrelevant for the determination of the money supply. (308)

Lombra's article concludes with a discussion on why, despite these important flaws, the multiplier approach continues to be popular among economists. The reason, he argues, is that when applied to longer term horizons the models track monetary growth reasonably well:

The model lives on with model-builders who are confirmed adherents to the Law of Parsimony and skilled in the use of Occam's Razor. The high correlations and identities so tightly linking reserves (or the base) and money over the longer run provide all the comfort most empiricists need to proceed as if the concerns noted above matter little. (312)

Still irrelevant?

Recently, Fed economists Seth Carpenter and Silva Demiralp concluded in their paper "Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy: Does the Money Multiplier Exist?" that the money multiplier is not a useful means of assessing the implications of monetary policy for money growth or bank lending in the US.

Not only does their paper discuss the institutional factors that render the money multiplier inoperable (including those discussed above), it also demonstrates empirically that the relationships between reserves and money implied by the money multiplier model do not exist.

These conclusions should, however, be viewed with caution given that the period under investigation in the paper ends in 2008, just prior to the Fed's shift toward the use of unconventional monetary policies.

Interestingly, Robert Hetzel now believes that the money multiplier model has actually gained relevance since the Fed started with its large-scale asset purchases in 2008.

Here is an excerpt from Hetzel's recent book, The Great Recession:

Starting in mid-December 2008 when the FOMC lowered its funds-rate target to near zero with payment of interest on bank reserves, the textbook reserves-money multiplier framework became relevant for the determination of the money stock. The reason is that the Fed's instrument then became its asset portfolio, the left side of its balance sheet, which determined the monetary base, the right side of its balance sheet. As a result, from December 2008 onward, the nominal (dollar) money stock was determined independently of the demand for real money. Although the reserves-money multiplier increased because of the increased demand by banks for excess reserves, the Fed retained control of M2 growth. Even if banks hold onto increases in excess reserves, the money stock increases one-for-one with open market purchases. (2012:237) (emphasis added)

In other words, Hetzel is saying that, as a result of its ability to determine the monetary base (B), the Fed now exercises considerable control over the change in deposits (D). And by doing so, Hetzel is suggesting that the Fed -- in one way or another -- is currently exploiting the money multiplier framework.

Here's a chart that appears to support Hetzel's claim:

The chart shows that since 2008 changes in B -- resulting from Fed asset purchases -- are clearly associated with changes in M**. For the period prior to 2008, there is no such relationship.

Hetzel's claim about the relevance of the multiplier approach could help to explain why some commentators have found causal relationships between changes in the monetary base and other variables for the period since December 2008.

For instance, Market Monetarist proponent Mark Sadowski recently pointed to empirical evidence that changes in the monetary base have had some causal role since December 2008:

I’ve done Granger causality tests on the monetary base over the period since December 2008 and find that the monetary base Granger causes the real broad dollar index, the S&P 500, the DJIA, commercial bank deposits, commercial bank loans and leases, the PCEPI, and 5-year inflation expectations as measured by TIPS.

So what's the bottom line? Does this mean the money multiplier model is now relevant?

On the one hand, I'm not convinced the model is entirely applicable (for instance, the textbook treatment implies that banks keep excess reserves to a minimum, which is obviously not the case today). On the other hand, it's unlikely that Hetzel is somehow wrong here.

Fortunately, I don't think it matters much one way or another, unless perhaps you are a Fed technician or an econometrician. What does matter is that the Fed currently exercises control over the monetary base. This, in itself, is a significant development for understanding the policy options now available to the Fed.

One thing is for sure, this recent development provides an excellent illustration of a crucial point often highlighted in Raymond Lombra's work:

The specific procedures ("policy rule") employed by the Fed and the reserve accounting regulations governing bank reserve management play a crucial role in determining causal relationships and system dynamics. (1992:309)

------

* The 'New View' focused on the role of assets, both real and financial, and the relative price mechanism in monetary analysis. From an operational standpoint, it contended that the Fed has little control over the money stock and that the money stock plays only a minor role in the transmission mechanism linking Fed actions to the real sectors of the economy.

** It's clear that the monetary base is not pulled upward due to increased deposit creation by banks.

References

Carpenter, S and S. Demiralp, Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy: Does the Money Multiplier Exist?", Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C.2010

Gilbert, R.A., Lagged Reserve Requirements: Implications for Monetary Control and Bank Reserve Management", Monthly Review, Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, 1980:

Goodfriend, M., A model of money stock determination with loan demand and a banking system balance sheet constraint", Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper, 1982

Goodfriend, M. and M. Hargraves, A historical assessment of the rationales and functions of reserve requirements, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper, 83-1, 1983

Hetzel, R., A Critique of Theories of Money Stock Determination, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper, 86-6, 1986

Hetzel, R., The Great Recession: Policy Failure or Market Failure, Cambridge University Press, 2012

Lombra, Raymond. Understanding the remarkable survival of multiplier models of money stock determination, Eastern Economics Journal, Vol 18, No 3, 1992

Maisel, S., Controlling Monetary Aggregates, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Conference Proceedings, 1971

Tobin, J., Commercial banks as creators of "money" 1963

The Old Keynesian prescription to get out of a deep recession

In my previous post, I highlighted an article that shows the most promising unconventional monetary policies for boosting ailing economies right now are overt monetary financing and the policy measures advocated by neo-chartalists.

It's worth mentioning that, from a practical standpoint, this is essentially what the traditional, Keynesian IS-LM model would prescribe in a context of high public debt combined with nominal interest rates at the zero lower bound.

A good example of the application of IS-LM toward this end is Robert Gordon's analysis of the difficulties facing Japanese policymakers in the 1990s:

If monetary policy is impotent because it cannot reduce the interest rate any further, a fiscal stimulus is required to end the slump and bring back the output ratio back to its desired level [...]

The low level of the Japanese interest rate created a policy dilemma in Japan. Monetary policy could not push interest rates appreciably lower, yet fiscal policymakers felt constrained in achieving a large fiscal stimulus by the high existing level of the fiscal deficit in Japan and by the fact that the public debt in Japan had reached 100 percent of real GDP.

However, the IS-LM model suggests a way out of the Japanese policy dilemma... [:] a combined monetary and fiscal policy stimulus that shifts the LM and IS curves rightward by the same amount can boost real GDP without any need for a decline in interest rates [...]