MMT

The "Noble Lie" on Public Spending and Inflation

[I suck at organising information. I've tried all sorts of fixes for this, both off-the-shelf and DIY. So now I'm going to just use tagged blog posts to organise things, so I can suck at this in public. No need to thank me.]

Introduction

Paul Samuelson, 1995

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] in every short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say “uh, oh what you have done” and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I see merit in that view.

Martin Wolf, 2020

In my view, [MMT] is right and wrong. It is right, because there is no simple budget constraint. It is wrong, because it will prove impossible to manage an economy sensibly once politicians believe there is no budget constraint.

Ross Gittins, 2020

But once demand was growing faster than the supply of real resources, any further money you created would simply cause inflation. This is what’s really worrying the opponents of MMT (and me). If you let the politicians off the leash to spend as much as they liked up to a point, how would you ever get them to stop once that point was reached?

We're edging towards a big change in how the economy is managed — Ross Gittins

Bill Gates Implicitly Endorses "Crazy Talk" MMT

On the one hand, I'm delighted that eminent self-made man William Henry Gates III has dismissed Modern Monetary Theory as "some crazy talk".

Gates worked his way up from practically nothing at Yale University (you've probably not heard of it) as the scion of a merely very wealthy family, to become an insanely wealthy entrepreneur. He did this upon realising that if you could copyright software (something legally uncertain at the time), you could then make an awful lot of money — from government-granted monopolies — over the wide use of the product of not an awful lot of work. His breakthrough insight was that one didn't have to wait for the establishment of legal precedent in order to begin exploiting it. Rather, you could do the two simultaneously. This proved to be his first and last history-changing innovation.

Since then Gates has been an unerring detector of, and proponent of, extraordinarily naff ideas destined for oblivion. The paradigmatic Gates bad idea came in 1995. The media famously dubbed 1995 "the Year of the Internet". In that year, Gates wrote a prophetic book full of naff ideas, and in passing he mused about the historical curiosity (nothing more than that) known as the Internet. It was, he thought, merely a signpost to the really significant online environment emerging, called the MicroSoft Network (MSN). Just as people were leaving proprietary, centralised online services like Compuserve and America OnLine in droves for the decentralised Internet, Gates was busily constructing his own new proprietary, centralised online service, because he knew a winning idea when he saw one.

So "crazy talk" is in effect a considerable endorsement of MMT by a man who will only begin to dimly perceive an undeniable truth after practically everybody else in the world has accepted it. First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they attack you, then Bill Gates ignores you and laughs at you, then you win.

On the other hand, the framing of MMT in this piece in the Verge is completely erroneous. It is misleading to say that MMT says (currency issuing) governments "need not worry about deficits because they can simply print their own currency" (emphasis mine). The scare word "print" here simply means "spend". A government spends its own money by issuing loose-leaf accounting records ("cash" to you and I), or by creating accounting entries on computers in the banking system. A currency issuing government must spend its own currency into the private sector before it can collect any of it back as taxes, fees, or fines. This "currency printing" is not novel, exceptional, radical, or crazy. It's a logical precondition of any sovereign monetary system.

Currency issuing governments cannot be said to spend any of the tax revenue they collect. Not one cent. When money is created, it is a financial liability for the government (an IOU, in effect), and a financial asset for the private sector. When the government collects money owing to it, it is merely cancelling out the liability against the asset (redeeming the IOU). Both the asset and the liability disappear in a puff of accounting. The government always spends newly created money. To claim that a currency issuing government normally uses "taxpayers' money", but in periods of wild abandon will resort to "printing money", is just flat-out wrong. Or worse, it is deliberate accounting fraud deployed for political purposes.

It is not that currency issuing governments can "print" money in order to spend; they cannot spend their own money any other way. As Warren Mosler says, the government neither has, nor does not have, any money. Or to put it another way, money isn't something a government has, it is something it does.

A further misrepresentation in the article is the claim that MMT proposes that governments should "manage inflation with interest rates". Not only do I not know of any major MMT scholar arguing any such thing, it would be hard to find any honest, knowledgable mainstream central banker who would endorse this position — and using interest rates to manage inflation is technically a major part of their job description!

Apologies for technobabble, but this is the short version: central banks (which implement monetary policy) can influence interest rates in the overnight market for funds required to settle the day's financial transactions between banks, and between banks and the government. This has a very, very weak, indirect, and unpredictable effect on private sector economic activity, and hence price stability. Much more direct and effective is the use of spending and taxation (fiscal policy) to ensure that there is neither too much money (inflationary) nor too little money (deflationary) for the goods available for sale in the economy as a whole, or in particular sectors of it.

The government uses money to achieve its (hopefully democratically determined) policy objectives. There is no alien thing out there called "the economy" which constrains how much money a government can create/spend or extinguish/tax. The limits on what we can achieve are the limits of our non-financial resources: raw materials, human beings, jam, etc.

As Modern Monetary Theory has hit so many radars that now even Bill Gates has heard of it, we can expect much more misrepresentation in future.

Which Keynesianism?

I posted this enormous torrent of blather on Blackboard the other day. It's mostly a restatement of stuff I've said before, but I'll repost it here for the purposes of copying and pasting in the likely case I have to restate it yet again elsewhere.

Because I've been studying economics for the last few years, rather than sticking to the curriculum and dutifully cultivating my employability, I feel obliged to chip in with a cautionary note: Almost all of the academic economists, and their policy prescriptions, which are characterised as Keynesian have nothing to do with the work of Keynes.

The post-war economic order established at Bretton Woods is conventionally understood as being Keynesian, but in fact Keynes was railroaded by the US representative Harry Dexter White, who insisted upon the system of fixed exchange rates pegged to the US dollar, with global dependency on holding US dollar reserves being greatly to America's benefit; the US gained the benefit of cheap foreign imports sold to acquire those reserves. Neither was Keynes responsible for the "Bretton Woods institutions", the World Bank and the IMF. His plan for regulating and settling international financial flows was considerably more humane than the usurious loans and standover tactics these institutions became notorious for.

Even "progressive" and "liberal" economists like Paul Krugman and Joe Stiglitz are members of the school of "New Keynesianism", a product of what Paul Samuelson called the "Neoclassical Synthesis"; taking some of the superficial trappings of Keynes' work and melding it with the earlier "neoclassical" school of economics, which Keynes actually intended to entirely overturn. Neoclassical models of the economy ignore the role of money and banking, believing that all economic transactions are ultimately barter transactions, and that money is therefore said to be "neutral", and banking is just redistribution of loanable funds, ultimately of no macroeconomic effect. Keynes wrote of this "Real-Exchange economics" (in an article unfortunately unavailable via SCU):

Now the conditions required for the "neutrality" of money, in the sense in which it is assumed in […] Marshall's Principles of Economics, are, I suspect, precisely the same as those which will insure that crises do not occur. If this is true, the Real-Exchange Economics, on which most of us have been brought up and with the conclusions of which our minds are deeply impregnated, […] is a singularly blunt weapon for dealing with the problem of Booms and Depressions. For it has assumed away the very matter under investigation.

This is the answer to Queen Elizabeth's question on how economists failed to see the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) coming; if the financial sector is macroeconomically neutral, as the neoclassicals claim, there cannot be any financial crises. However, outside the neoclassical tradition, the normal functioning of the economy, and the pathologies leading to crises, are well understood:

- The Chartalists determined that all money is credit, ultimately issued by the state. Michael Hudson recently did some exhaustive historical work on this, which David Graeber popularised in his book Debt: the First 500 Years.

- Wynne Godley showed how currency-issuing states must spend more than they tax if the private sector is to have the money necessary to spend and save.

- Irving Fisher identified the role of debt deflation in turning a rush to liquidate debt into an ongoing crisis where outstanding debts become impossible to repay.

- Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis extended Fisher's work to describe how financial crises arise from the normal workings of a capitalist economy.

- Keynes implicitly regarded the money economy as a tool for allocating real resources in pursuit of public policy objectives, a principle explicitly formulated by Abba Lerner as "functional finance". This is in opposition to the neoclassical intuition that a household is like an individual, a firm is like a household, and a government is like a firm; therefore a government must follow the principles of "sound finance" and "live within its means".

- All of the above are incorporated in the teachings of "Post-Keynesian" economics, which Keynes' biographer Robert Skidelsky considers closest to Keynes' own thinking. The sub-field of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) synthesises all of these into a single coherent framework for analysing the economies of countries which issue their own currency.

By the end of World War II, functional finance was so well established as to be almost universally understood to be common sense. The 1945 White Paper on Full Employment in Australia, prepared for John Curtin by H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, and based on the principles in Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, declared:

It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

(Emphasis mine.) As expressed by MMT, currency-issuing governments are not fiscally constrained. The only limits on public policy are real resource limits. During the last UK election campaign, Theresa May was vehemently insisting "there is no magic money tree". But in fact there is: it's called the Bank of England (we have the Reserve Bank of Australia), and Her Majesty's Treasury has an unlimited line of credit there. Whenever the government wants to spend, the Bank of England just credits the accounts of commercial banks. I was delighted when while campaigning May was confronted by a furious protester wanting to know "Where's the magic doctor tree? Where's the magic teacher tree?" The policy limits we should be worried about are real resources (including people), not money.

Nevertheless, mainstream economists and politicians believe, in some vague way, that (as Stephanie Kelton puts it) "money grows on rich people". So it's not surprising to read already on the discussion boards here that Keynesianism is all very desirable, but how will the federal government pay for it? This is a meaningless question. The government will pay for it like it pays for anything: by spending the money into existence. That's where all money comes from, net of private sector credit creation. Logically, it can't come from anywhere else. If the government were to try to achieve fiscal (or, conflating governments and firms again, "budget") surpluses over the long term by taxing more than they spend, as neoclassicals, including New Keynesians, recommend, they would merely be draining savings from the private sector for no good reason. State-issued money is an IOU, a tax credit. When the credit is redeemed it ceases to exist. The government doesn't have to tax in order to spend. It has to spend in order to tax. Think about it: where else would the first dollar ever taxed come from?

Now you might be thinking, hang on: what about the most fiscally responsible government we've ever had (Howard/Costello) and their record run of "budget" surpluses? The economy was going gangbusters! Okay, here's the fiscal balance for that period:

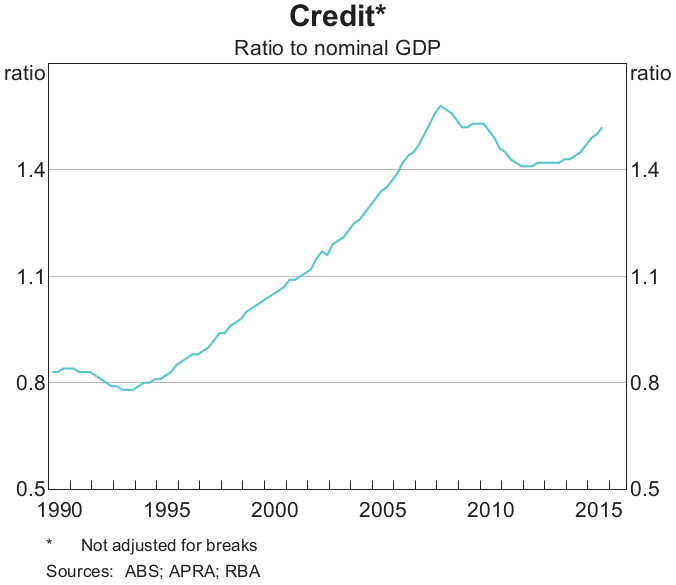

As with every currency-issuing sovereign state in history, deficits are the rule, not the exception. Here's what happened to private sector debt over the same period:

(Data from the Bank of International Settlements and OECD.) As soon as the government started taxing more than it spent, private sector debt took off, and subsequent fiscal deficits were insufficient to reverse the damage. Notably, at the same time household debt overtook corporate debt, as credit was used to sustain consumer demand, not to mention standards of living, rather than for investment in productive capacity. Australia "Nimbled it, and moved on", and to hell with the consequences.

Australia recently passed two milestones of note: total private sector debt (the blue line above) exceeded 200% of GDP — at roughly the level that Japan's private debt was at in the early 90s when its real estate bubble burst — and bank equity in residential real estate passed 50%. That's 50% of the total residential real estate stock, not just houses built in the last x years. Minsky describes the path to financial collapse as progressing through the stages of "hedge finance", then "speculative finance", and finally "Ponzi finance". When you see phenomena like interest-only mortgages — where the principal is never repaid, on the assumption that housing prices only ever go up, and the debt will be settled whenever you sell the property, presumably pocketing a tidy and lightly-taxed capital gain at the same time — you know which stage you're in.

So why does nobody in mainstream politics or economics know anything about this? To put it succinctly, because neoliberalism. On the left, the "balancing the books" rhetoric serves a useful purpose: it gives you a disingenuous pretext to do what you want to do anyway that is compatible with the dominant paradigm. As Randy Wray said at a recent MMT conference:

"[Progressives] link the good policies they want to 'we'll tax the rich to pay for it'. So when you point out we don't need to tax the rich to pay for it, they're just crestfallen because they want to tax the rich. So I say 'Of course we should tax the rich. Why? They're too rich.' You don't need any other argument than that."

Taxes drive demand for the currency. If you know you have to pay taxes, you will work to get the money to pay for it. It's a coercive way for the government to mobilise labour to achieve its policy objectives, but assuming policy is arrived at democratically, it's relatively fair and vastly preferable to the autocratic alternative of having a gun put to your head. Taxes are also a fiscal instrument that can be used to discourage certain kinds of behaviour, and harmful social phenomena (like income inequality).

In the neoliberal era, that's why Australia has a retrospective tax on education called HECS-HELP, which in turn is why SCU has no school of history, or philosophy, or in fact any of the traditional academic disciplines. Students know that their education will be retrospectively taxed, so they can't afford to choose disciplines unlikely to offset that tax with increased earnings. There are twice as many universities as there were in 1988, but the new ones are glorified vocational colleges with next to no permanent academic staff. Australian post-Keynesian economist Steve Keen, who correctly predicted — and more importantly, explained — the GFC, subsequently lost his job at the University of Western Sydney when they closed down their economics department. Who needs academic economics when you have business studies courses, after all? He ended up at Kingston University in London, another young neoliberal institution, where last year he was given an ultimatum to spend more hours teaching or take a significant pay cut. He's ended up having to put his hat out for donations from the public in order to continue his work as a public intellectual.

Why would public policy function like this? Why would policy makers want a population uneducated about how the world actually works, and instead merely trained in how to work in it? Why is the conventional wisdom so full of assertions that are demonstrably untrue, and profoundly damaging to society? Paul Samuelson, author of the macroeconomics textbook that gave generations of undergraduates a completely misleading interpretation of Keynes' work explained this in an interview:

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] in every short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say "uh, oh what you have done" and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I see merit in that view.

So basically, belief in myths must be maintained among the general population wherever doing so provides support for the elite political preference for small government, i.e. for control over the economy to be exercised by private finance rather than public fiscal policy. This is what neoliberalism fundamentally is, an Orwellian fiction imposed on a deliberately dumbed-down populous, with access to the truth as much the reserve of a select educated elite as ever. "Long-run civilised life" has been restored, thanks to neoliberalism's making of the 21st century by its un-making of the 20th.

I could go on forever (evidently) but others explain all this better than I:

- Here's a short interview with Steve Keen explaining how neoliberal austerity economics leads inevitably to financial crises.

- Stephanie Kelton is probably the best person to explain MMT to a general audience. Watch her describe the Angry Birds Approach to Understanding Deficits in the Modern Economy.

- Here's Bill Mitchell explaining in 15 minutes how fiscal policy works in the real world.

- Warren Mosler explains here why fiscal deficits are generally desirable. If you find reading easier than listening, I recommend Warren's slim volume (and even slimmer PDF file) Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy.

If you have read this far, I admire your tenacity.

'Straya: Basically, she's rooted mate

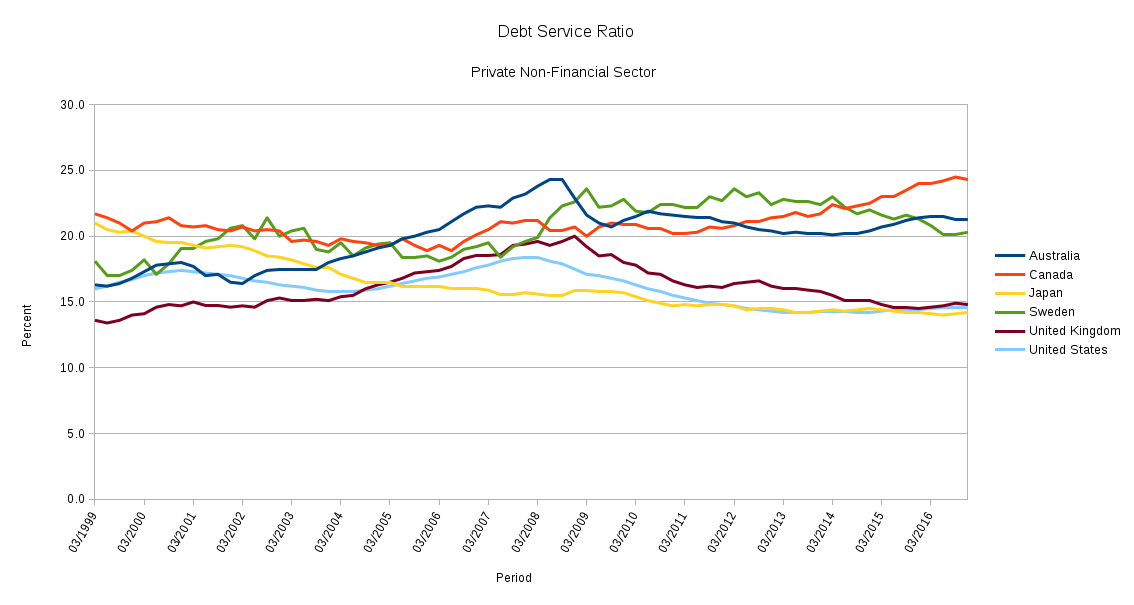

Charts! Nobody asked for them, but I have them anyway! Over the last few years the Bank for International Settlements have been publishing a fab set of statistics that are not usually brought to bear in the tea leaf reading of mainstream economists. This is a shame, as they are exactly the sort of statistics which would indicate the risk of imminent financial crisis. Last month the BIS updated the data to the end of (calendar year) 2016. Here's an illustration (courtesy of LibreOffice) of where Australia is, relative to some comparable and/or interesting countries (click to embiggen):

As the BIS explains, the Debt Service Ratio (DSR):

"reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises. Furthermore, a high DSR has a strong negative impact on consumption and investment."

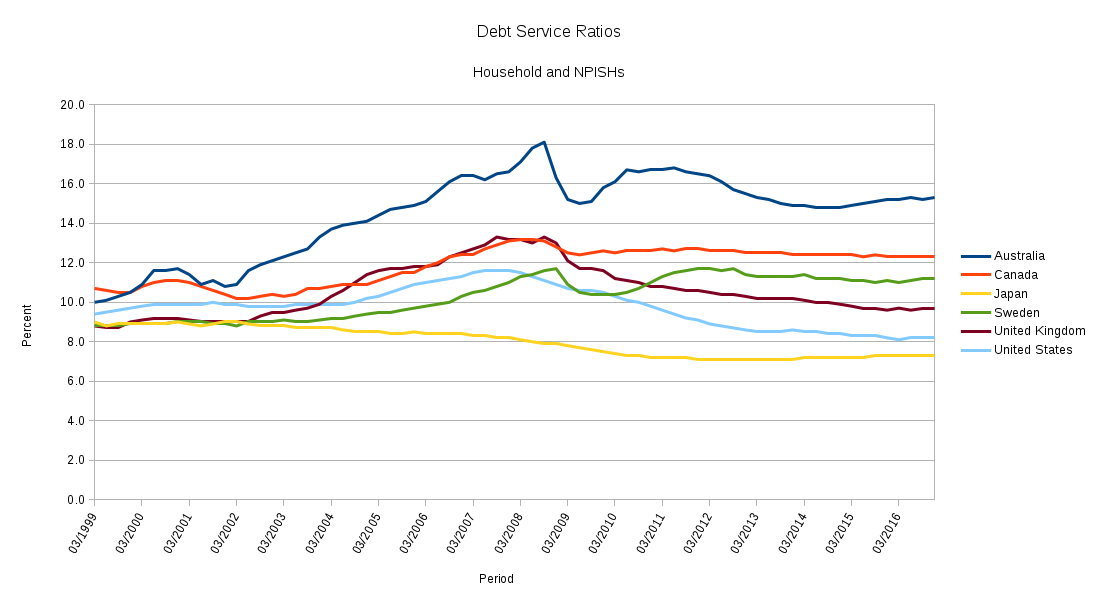

So as a measure of Australia's ability to pay at least the interest on our private sector debts, if not pay down the principal, you might think this is not a bad result. We clearly substantially delevered after the GFC, thanks in large part to the Rudd stimulus pouring public money into the private sector, then levered up a bit since, but we've ended up between Canada and Sweden, which is a pretty congenial neighbourhood. But this is total private sector debt; what happens when we take business out of the equation and just look at households (and non-profit institutions serving households - NPISHs)?

Woah! Suddenly we're in a league of our own. Canada's flatlined here since the GFC, meaning the subsequent increase in their total private debt burden has largely come from investment in business capital. In such a case, provided this investment is directed at increasing productive capacity, and is accompanied by public sector spending to proportionally increase demand, this is sustainable debt. Australia has been doing the opposite.

Here's another way of looking at the coming Australian debt crisis, private sector credit to GDP:

This ratio will rise whether the level of debt rises, GDP falls, or both, so it's another good indicator of unsustainable debt levels. The current total level (in blue) of over 200% is at about the ratio Japan was at when its real estate bubble burst in the early 1990s. Breaking this down again into household and corporate sectors, we see that over the mid-1990s Australia switched the majority of its private sector borrowing from business investment to sustaining households. What happened in the mid-90s? Data here from the OECD:

From the mid-1990s to 2007 Australia experienced the celebrated run of Howard/Costello government fiscal (or "budget") surpluses. We all know, or should know, thanks to Godley's sectoral balances framework, what happens when the public sector runs a surplus: the private sector must run a corresponding deficit, equal to the last penny. There is nowhere else, net of private sector bank credit creation (which zeroes out because every financial asset created in the private sector has a corresponding private sector liability), for money to come from. When the government taxes more than it spends, it is withdrawing money from the private sector. Mainstream economics calls this "sustainable", and "sound finance", meaning of course it is nothing of the sort.

How did the private sector, and the household sector in particular, continue to spend from that point onward, behaving as though losing money (not to mention public infrastructure and services) down the fiscal plughole was not merely benign but quite wonderful? It chose to Nimble it and move on, going on a massive credit binge. The banks were happy to provide all the credit demanded, because the bulk of the lending was ulitimately secured by residential real estate prices, and these were clearly going to keep rising without limit (thank heavens, because if they were to fall like they did in the US in 2007…).

The Global Financial Crisis put a dent in the demand for credit, but as subsequent government fiscal policy has tightened, under the rubric of "budget repair", it is rising again. We are already in a state of debt deflation: Australia's household debt service ratio (as above), at between 15 and 20 percent of household income for over a decade, has dampened domestic demand, leading to rising unemployment and underemployment, leading to more easy credit as a quick fix for income shortfalls ("debtfare"). More of what income remains is redirected to debt servicing rather than consumption, and so we spiral downwards, our incomes purchasing less and less with each turn. [I will post more about some of the social and microeconomic consequences in (over-)due course.]

The Australian government needs to spend much, much more - and quickly. Modern Monetary Theory, drawing on an understanding of the nature of money that goes back a century, shows us that government spending (contrary to conventional wisdom) is not revenue-constrained; a currency-issuing government can always buy anything available for sale in the currency it issues. There is nothing about our collective "budget" that needs repairing before we can do so. The same data from the OECD shows that most currency-issuing governments with advanced industrial economies run fiscal deficits almost all the time:

In fact, under all but exceptional conditions, government fiscal surpluses (i.e. private sector fiscal deficits) are a recipe for recession or depression. The greater the surplus, the greater the subsequent government spending required to lift the private sector out of crisis, as can be seen above in the wild swings in neoliberal governments' fiscal position from the mid-90s on. The fiscal balance over any given period is nothing more than a measurement of the flow of public investment into the private sector. What guarantees meaningful sustainability is a government's effective use of functional finance to manage the real (as opposed to financial) economy in pursuit of public policy objectives. Refusing to mobilise idle resources (including, crucially, labour) for needed public goods and services is not "sound finance"; it is the very definition of economic mismanagement, as was once widely recognised:

"It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

"In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

"Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

"The policy outlined in this paper is that governments should accept the responsibility for stimulating spending on goods and services to the extent necessary to sustain full employment. To prevent the waste of resources which results from [un]employment is the first and greatest step to higher living standards."

We chose to forget all this from the 1980s onward. We can choose to remember it at any time.

Wednesday, 15 February 2017 - 5:22pm

I'm ranting altogether too much over local "journalism", and this comment introduces nothing new to what I've posted many times before, but since the Advocate won't publish it:

Again I have to wonder why drivel produced by the seething hive mind of News Corp is being syndicated by my local newspaper. This opinion comes from somebody who appears to be innumerate (eight taxpayers out of ten doesn't necessarily - or even very likely - equal eight dollars out of every ten) economically illiterate, and empirically wrong.

Tax dollars do not fund welfare, or any other function of the federal government. Currency issuing governments create money when they spend and destroy money when they tax. "Will there be enough money?" is a nonsensical question when applied to the federal government. As Warren Mosler puts it, the government neither has nor does not have money. If you work for a living, it is in your interest that the government provides money for those who otherwise wouldn't have any, because they spend it - and quickly. Income support for the unemployed becomes income for the employed pretty much instantly. Cutting back on welfare payments means cutting back on business revenues.

And the claim that the "problem" of welfare is increasing in scale is just wrong. Last year's Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) report shows dependence on welfare payments by people of working age declining pretty consistently since the turn of the century. This opinion piece is pure class war propaganda. None of us can conceivably benefit in any way from pushing people into destitution in the moralistic belief that they must somehow deserve it.

The Joy of Economic Irresponsibility: or how I learned to stop worrying and love the public debt

If there's one thing I've learned in the last year that I think is so important it's worth shouting from the rooftops, it's that simultaneously studying economics and the psychology of stress while also being personally stressed about money is a very, very bad idea.

If there are two important things I've learned in the last year, I'd say that the more generally applicable one to the citizen in the street is that a government which issues it's own money can never run out of it.

Such a government can of course pretend, or at least behave like, it can run out of money. In fact, many have done so for the last thirty years or so, and the results have been disastrous. You don't have to take my word for it. Here are some graphs, mostly from the RBA Chart Pack, except where otherwise indicated. Here's the Australian government fiscal balance, misleadingly labelled "budget balance" as per the conventional misunderstanding of reality.

Things took a dip from 2007/8, but deficits are improving, and we were in surplus for most of the preceeding decade. And that's good, isn't it? Surpluses mean we have more money, don't they?

Generally, yes. A "budget surplus" for a business or household means more money at hand to spend later. However, for an economy with a sovereign-currency-issuing government, public fiscal surpluses mean we have less money.

How is this possible? To understand this, you have to understand that accountancy—specifically double-entry bookkeeping and balance sheets—is the foundation of economics; at least economics of a realistic kind. All money is credit money. You make money—literally—by being in debt to somebody, and by denominating this debt in the country's transferrable unit of account. Spending is the simultaneous creation of a debt on the buyer's side of the ledger, and a corresponding credit on the seller's side. However, if you happen to hold enough credits that have already been generated as the flipside of a debt in your favour, you can use these credits to immediately cancel the debt of the current transaction. One way most of us do this on a daily basis is by using cash. Cash is a transferrable token of public sector debt and private sector credit.

Three percent of the immediately-spendable money in the private sector is in the form of cash. The other 97% is just numbers stored on computers in the commercial banking sector. Most of this is money that originated as commercial bank loans, and will disappear from the bank's balance sheets as those loans are repaid (though of course in the meantime more loans will have been made). However, a significant amount of money originates as loans the government makes to itself (technically the central bank lends to the treasury), eventually ending up in the private sector as cash, or (through a mindbending process I will mercifully omit from this account) as commercial bank deposits. A currency-issuing government can always lend more money to itself in order to spend, and never has to pay it back. It follows that such a government does not need to tax in order to spend, and only ever taxes for other reasons. Economics textbooks, and economic commentators, routinely get this utterly and comprehensively wrong. Consider this textbook description of economic "automatic stabilisers":

"During recessions, tax revenues fall and welfare payments increase thereby creating a budget deficit. In times of economic boom, tax revenues rise and welfare payments fall creating a budget surplus."

Budget deficits are not an eventual consequence of government spending; the spending and the creation of a debt are the same operation. Tax revenues merely redeem a part of the already-accrued debt; the money issued by public spending is a public IOU that effectively disappears when private parties use it settle their tax debt owed to the public. Tax revenues therefore cannot be used to fund public spending; in order to spend, new public debt must be issued. The automatic stabilisers are real (assuming a somewhat sensible tax system), but the important part of their function is on the private side: injecting new money to stimulate demand when needed, or putting the brakes on dangerous speculative activity in a boom. The government's fiscal position from one year to the next is an inconsequential side-effect.

Taxation is the elimination of money, and hence of the demand for goods, services, and assets that drives the private sector economy. Don't believe me? Lets take a wider focus on the fiscal balance numbers above:

[Source]

Generally, and especially prior to the neoliberal period, public fiscal surpluses are the exception, not the rule. And for a good reason; it's generally not a good idea to drain demand out of the economy. So what happens when you toss good sense aside, and insist on surpluses for their own sake? Here's what happened to public sector debt:

I'm presuming (the ABS Chart Pack doesn't specify) that this is debt owed to private sector banks in the form of loans and government securities. I should stress that, as with taxation, these operations are not required to finance spending, and are only ever done for other reasons (such as hitting interest rate targets). Also, because they don't issue currency themselves (though this is possible, and has worked elsewhere), lower levels of government do have to rely in part on revenue-raising to fund spending, though grants from the federal government also play a big part in determining their fiscal position.

Still—phew!—we got that scary public sector debt under control until the GFC, and we can do it again! But hang on, if that's taking money out of the private sector, where does the private sector get the money to sustain demand? Here's the private sector debt over the same period:

Note that this is one and a half times GDP, compared to the one third of GDP outstanding to the public sector, at the height of its alleged fiscal irresponsibility. When government self-imposes limits on its ability to spend, private sector credit creation takes up the slack. Who do you want controlling how much money is created, who gets it, and what it gets spent on? A mix of the commercial finance sector and a (somewhat) democratically-accountable government? Or just the bankers?

Most of private-sector money creation is commercial bank loans, and as economist Michael Hudson notes, in the US, UK, and Australia, 70 percent of bank loans are mortgages. That's a hell of a lot of money (what's 70 percent of one and a half times GDP?) dependant for its existence on the soundness of pricing for a single class of asset. If real estate prices suddenly crash, and mortgagees start to default on their loans, poof! The corresponding credits on the other side of the ledger are gone too, and the real estate sector takes the whole economy down with it. You can't argue with balance sheets.

Still, I expect we'll be fine as long as we stay the fiscal responsibility course, and don't let the government "spend more than it earns". Real estate prices only ever go up, don't they? And it's not like bankers would ever be led by their own short-term interests to make a huge amount of risky loans and inflate an enormous real estate price bubble…

Thursday, 11 February 2016 - 1:39pm

I'm reluctant to contribute to the Piketty backlash, as it seems to me to be mostly motivated by the unrealistic expectation that his book should have provided a comprehensive theory of everything. However this blog post from Alexander Douglas provides such a pithy account of the workings of public fiscal balances that it's worth recirculating. In response to the claim that "there are two main ways for a government to finance its expenses: taxes and debt," he writes:

Government spending isn’t financed by anything. The government pays for everything by crediting the non-government sector (employees, companies, foreign governments, etc.) with financial claims. Some of these claims are returned to the government in order to settle liabilities to the government (for instance in tax payments); others remain as financial holdings for the non-government sector. At any given moment the claims remaining as financial holdings constitute the whole of the ‘public debt’.

Tax revenue largely depends on the volume of spending. Decisions to spend rather than save are largely at the discretion of non-government agents. It is therefore very misleading to speak, as Piketty does, as if the government chooses to ‘finance its spending’ through taxation or debt. The amount of government spending that remains as ‘debt’ is largely up to the discretion of non-government agents choosing whether to hold onto financial claims or pass them on so that they can eventually find their way back to the government.

It therefore makes no sense to panic about government "budget" deficits, if you're not also going to bemoan private savings. Ironically, as it happens, private savings currently is a big problem, as corporations hand out mattress stuffing — in the form of dividends and share buybacks — rather than investing. Yet more ironically, the appropriate response is for the government to make up the investment shortfall through large fiscal deficits. Otherwise the economic stagnation rolls on until (sorry, I can't resist it) r>g.