Australia

'Straya: Basically, she's rooted mate

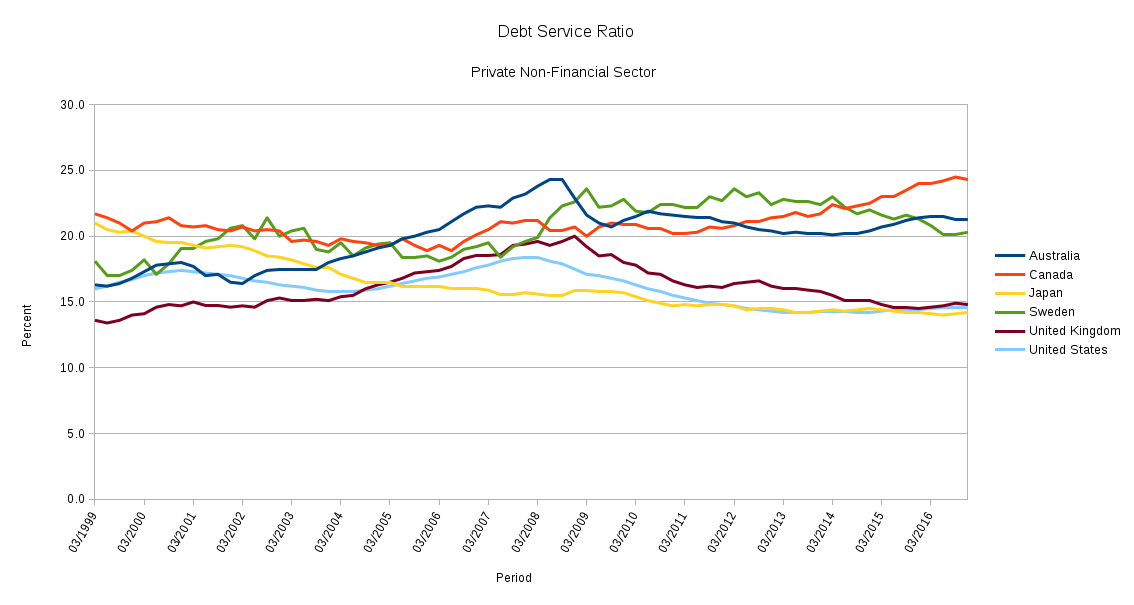

Charts! Nobody asked for them, but I have them anyway! Over the last few years the Bank for International Settlements have been publishing a fab set of statistics that are not usually brought to bear in the tea leaf reading of mainstream economists. This is a shame, as they are exactly the sort of statistics which would indicate the risk of imminent financial crisis. Last month the BIS updated the data to the end of (calendar year) 2016. Here's an illustration (courtesy of LibreOffice) of where Australia is, relative to some comparable and/or interesting countries (click to embiggen):

As the BIS explains, the Debt Service Ratio (DSR):

"reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises. Furthermore, a high DSR has a strong negative impact on consumption and investment."

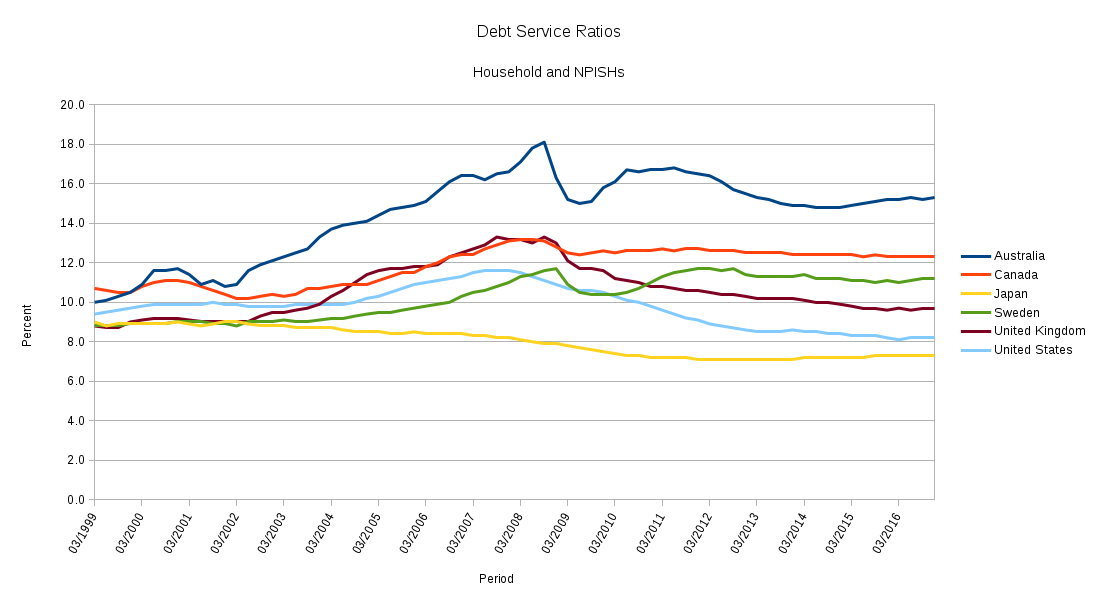

So as a measure of Australia's ability to pay at least the interest on our private sector debts, if not pay down the principal, you might think this is not a bad result. We clearly substantially delevered after the GFC, thanks in large part to the Rudd stimulus pouring public money into the private sector, then levered up a bit since, but we've ended up between Canada and Sweden, which is a pretty congenial neighbourhood. But this is total private sector debt; what happens when we take business out of the equation and just look at households (and non-profit institutions serving households - NPISHs)?

Woah! Suddenly we're in a league of our own. Canada's flatlined here since the GFC, meaning the subsequent increase in their total private debt burden has largely come from investment in business capital. In such a case, provided this investment is directed at increasing productive capacity, and is accompanied by public sector spending to proportionally increase demand, this is sustainable debt. Australia has been doing the opposite.

Here's another way of looking at the coming Australian debt crisis, private sector credit to GDP:

This ratio will rise whether the level of debt rises, GDP falls, or both, so it's another good indicator of unsustainable debt levels. The current total level (in blue) of over 200% is at about the ratio Japan was at when its real estate bubble burst in the early 1990s. Breaking this down again into household and corporate sectors, we see that over the mid-1990s Australia switched the majority of its private sector borrowing from business investment to sustaining households. What happened in the mid-90s? Data here from the OECD:

From the mid-1990s to 2007 Australia experienced the celebrated run of Howard/Costello government fiscal (or "budget") surpluses. We all know, or should know, thanks to Godley's sectoral balances framework, what happens when the public sector runs a surplus: the private sector must run a corresponding deficit, equal to the last penny. There is nowhere else, net of private sector bank credit creation (which zeroes out because every financial asset created in the private sector has a corresponding private sector liability), for money to come from. When the government taxes more than it spends, it is withdrawing money from the private sector. Mainstream economics calls this "sustainable", and "sound finance", meaning of course it is nothing of the sort.

How did the private sector, and the household sector in particular, continue to spend from that point onward, behaving as though losing money (not to mention public infrastructure and services) down the fiscal plughole was not merely benign but quite wonderful? It chose to Nimble it and move on, going on a massive credit binge. The banks were happy to provide all the credit demanded, because the bulk of the lending was ulitimately secured by residential real estate prices, and these were clearly going to keep rising without limit (thank heavens, because if they were to fall like they did in the US in 2007…).

The Global Financial Crisis put a dent in the demand for credit, but as subsequent government fiscal policy has tightened, under the rubric of "budget repair", it is rising again. We are already in a state of debt deflation: Australia's household debt service ratio (as above), at between 15 and 20 percent of household income for over a decade, has dampened domestic demand, leading to rising unemployment and underemployment, leading to more easy credit as a quick fix for income shortfalls ("debtfare"). More of what income remains is redirected to debt servicing rather than consumption, and so we spiral downwards, our incomes purchasing less and less with each turn. [I will post more about some of the social and microeconomic consequences in (over-)due course.]

The Australian government needs to spend much, much more - and quickly. Modern Monetary Theory, drawing on an understanding of the nature of money that goes back a century, shows us that government spending (contrary to conventional wisdom) is not revenue-constrained; a currency-issuing government can always buy anything available for sale in the currency it issues. There is nothing about our collective "budget" that needs repairing before we can do so. The same data from the OECD shows that most currency-issuing governments with advanced industrial economies run fiscal deficits almost all the time:

In fact, under all but exceptional conditions, government fiscal surpluses (i.e. private sector fiscal deficits) are a recipe for recession or depression. The greater the surplus, the greater the subsequent government spending required to lift the private sector out of crisis, as can be seen above in the wild swings in neoliberal governments' fiscal position from the mid-90s on. The fiscal balance over any given period is nothing more than a measurement of the flow of public investment into the private sector. What guarantees meaningful sustainability is a government's effective use of functional finance to manage the real (as opposed to financial) economy in pursuit of public policy objectives. Refusing to mobilise idle resources (including, crucially, labour) for needed public goods and services is not "sound finance"; it is the very definition of economic mismanagement, as was once widely recognised:

"It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

"In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

"Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

"The policy outlined in this paper is that governments should accept the responsibility for stimulating spending on goods and services to the extent necessary to sustain full employment. To prevent the waste of resources which results from [un]employment is the first and greatest step to higher living standards."

We chose to forget all this from the 1980s onward. We can choose to remember it at any time.

Canadian Election Shows Neoliberals CAN be Defeated

Australian progressive movements know that this federal election will be a crucial marker for many core issues: climate, jobs, inequality, fair taxation, globalisation, and more. The re-election of the Turnbull government, which has kept intact the harsh agenda of Tony Abbott but put a new face on it, would mark a setback for all of these campaigns. Yet while mobilising as energetically as possible during the campaign, and welcoming the visible erosion in public support for Coalition trickle-down policies, activists naturally worry that the government may be re-elected anyway.

Canada held a federal election on October 19 last year, and the results – while far from perfect – confirm that activist movements really can affect electoral outcomes. Moreover, the results prove that the influence of progressive movements is felt in ways that go beyond the traditional “horse race” between parties, and can reach more deeply into political culture and “common sense” values. This post will briefly review the Canadian result, and consider several lessons arising from that experience for Australian progressives.

The Canadian Electoral Landscape

Canada was ruled from 2006 through 2015 by a hard-right Conservative government led by Stephen Harper. There were numerous parallels between the Harper agenda and Australia’s conservative leaders (first John Howard, then Tony Abbott). Indeed, the Conservatives borrowed liberally from the calculated, opportunistic electoral strategies of their Australian counterparts – right down to contracting the services of Lynton Crosby (the so-called “Wizard of Oz,” architect of several Australian Liberal campaigns) as a key advisor.

Harper was limited to a minority mandate during his first two terms (in 2006-2008 and 2008-2011), and hence his legislative power was constrained accordingly. But in 2011 he prevailed with a majority, and that is when the full force of his harsh agenda was imposed on Canadians. Under Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system, majority governments can be attained with a surprisingly small share of the vote: Harper won his in 2011 with only 39% popular support. Vote-splitting and harsh competition among the opposition parties (including the centrist Liberals, the social-democratic NDP, and the Greens) helped facilitate this perverse outcome. Harper’s majority tenure was marked by a sharp pro-business shift in economic policy (especially favouring the petroleum industry), fierce attacks on union rights and labour standards, regressive tax changes (including lower corporate taxes, huge loopholes for financial investors, and tax subsidies for stay-at-home parents), and great damage to Canada’s once-respected international reputation (including teaming up with Abbott to sabotage global climate negotiations).

Anyone with a progressive bone in their body knew that if Harper was re-elected (especially with another majority), these painful changes would be cemented for decades. Harper’s growing arrogance and corruption within Conservative ranks undermined his political momentum going into the election. But his carefully calculated platform, strong campaign skills, and the siren call of further regressive tax cuts, still posed a dangerous threat. Progressives agreed that preventing another Conservative victory was a political priority of historic proportions. And for most, that goal superseded any loyalties to a particular political party.

Activist strategies were further influenced by a continuing no-holds-barred battle among the opposition parties. The NDP was emboldened by strong performance in 2011 under the charismatic Jack Layton (who tragically died shortly after the election), and had its sights set (not very realistically) on forming government for the first time. New leader Thomas Mulcair engineered a substantial move to the centre, hoping to further cement the party’s credibility as a “government in waiting.” Meanwhile, the Liberals, consistent with their own history, portrayed themselves as more progressive than they actually are (“run from the left, rule from the right,” is the slogan that sums up Liberal strategy!). The Greens have never held more than two seats in Parliament, but often attract enough votes (high single digits) to prevent riding victories by the other parties. Amidst this continuing and unrepentant in-fighting between the opposition parties, activist movements understandably tried to rise above this battle of party logos. Most focused their electoral efforts on exposing and damaging Harper, and mobilising an “anything but Conservative” sentiment.

The Economic Context

The Conservatives’ chances were further damaged by the poor performance of Canada’s economy in the period leading into the election. The much-vaunted oil boom, led by enormous bitumen projects in northern Alberta, went bust along with global commodity prices. Where Harper had once boasted of Canada as a new “energy superpower,” by 2014 the costs of Canada’s unthinking extractivism (including painful de-industrialisation, an overvalued currency, and terrible environmental performance) were increasingly apparent. Canada’s economy actually slipped into an official recession in the first half of 2015 (defined as two consecutive quarters of shrinking real GDP), due primarily to the sharp contraction in energy-related business investment.

Poor economic numbers posed a sharp contrast to the traditional assumption (promoted so loyally by the commercial media) that Conservatives are “naturally” the best economic managers. Progressive campaigns pounced with strong arguments that a change in direction (emphasising job creation, physical and social infrastructure, environmental investments, and more) would strengthen Canada’s economy. This helped voters break out of the traditional “economy versus values” frame that has traditionally benefited Conservatives. (One example of this work was a major project by Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector trade union, proving that Canada’s economy in fact performed worse under Stephen Harper than any other government in the postwar era.)

The Union Movement and the Election

Canada’s union movement also played an important role in defeating the Harper Conservatives. They directed major resources into educating and mobilising union members, tying their campaign to key union and labour issues. Here, too, the strategy was nuanced, influenced by recognition that defeating Harper was the top priority. Most union campaigns focused on the ideas and issues at stake, rather than explicitly instructing their members to vote for a particular party. (A few unions still advocated voting for the NDP as their main message.) By linking Harper’s rule to attacks on unions, the rise of inequality, and the failure to create jobs, unions were able to maximise their credibility as a genuine but largely non-partisan voice for workers’ interests during the election. (In this regard, the unions’ campaign was reminiscent of the successful “Your Rights at Work” campaign run in Australia by the ACTU and its affiliates in 2006-07.)

A Stinging Defeat

Lasting nearly 12 weeks, the official campaign was the longest in modern Canadian history (Harper hoped a long campaign would benefit the Conservatives, who had the strongest financial base of any party). After many twists and turns (all 3 major parties led the polls at some point during the campaign), momentum shifted decisively to the Liberals in the last days. This was because anti-Harper voters eventually decided the Liberals had the best chance of unseating the government, and hence shifted their support there – causing a self-reinforcing snowball effect. Mulcair’s conservative economic platform (he consciously positioned the NDP to the right of the Liberals on several key issues, including balancing the budget and rejecting higher taxes on rich Canadians) squandered the NDP’s chance to capitalise on Canadians’ strong desire for change. The Liberals won a majority (with 39% of the vote, almost exactly as Harper did in 2011), the NDP lost over half its seats and a third of its vote, and the Conservatives remain a strong, unapologetic opposition (winning over 30% of the vote despite negative anti-Harper sentiment across the country).

The new Liberal government, under the charismatic Justin Trudeau (son of Pierre Trudeau, perhaps Canada’s most progressive Prime Minister), acted quickly on several high-profile issues: including appointing a cabinet with full gender equity, dramatically shifting Canada’s stance at the Paris climate talks, and fully revoking two of Harper’s anti-union bills. However, after picking that low-hanging fruit and cementing its aura as an agent of “change,” the longer-run character of this government remains unclear and contested. Liberals have strong connections with big business, and are not likely to fundamentally shift the direction of Canadian policy without strong active pressure from the same movements and campaigns that made such a difference in the election. Nevertheless, the defeat of Harper is a huge positive step for Canadian politics and policy, and opens the door to further issue-based activism and further victories.

Lessons for Australia

Some key lessons from the Canadian experience, that may be relevant in the Australian campaign, include:

- It is essential to challenge the economic credibility of the neoliberal government, and show concretely that most Australians would be materially better off with a change in direction. This undermines the traditional assumption that neoliberals know best how to “manage” the economy, and that any change in direction would risk Australians’ jobs and prosperity. The failures of neoliberal policy are abundant, and provide plenty of ammunition for this effort; these arguments work best when described in concrete material terms (jobs, incomes, security, equality), not in economic jargon (“confidence,” “rationalism,” “efficiency”).

- The ongoing battle of ideas in society is not synonymous with, and in many ways more important than, the electoral competition between parties. If progressive campaigns succeed in shifting the goalposts of received “common sense” around key issues and values, they can force politicians of all stripes to change their orientation accordingly to keep up. The Coalition government’s enactment of limits on tax preferences for high-income superannuation funds is an example of this effect.

- And by making an independent, non-partisan appeal to core values, and emphasising the importance of those values to the future quality of life and cohesiveness of society, activist movements can do great damage to the credibility and appeal of the ruling agenda.

This is not to deny the importance of partisan activism in successful election campaigns. Of course we need principled progressive parties to support the demands of the activist movements, assemble composite platforms, and meaningfully challenge the right to govern of the existing government. But parties will naturally be guided by their own immediate interests and calculations. That’s where the ongoing activism of issue-oriented campaigns and movements is essential if we are indeed to create “losing conditions” for a conservative government.

This article originally appeared in Australian Options magazine, and is reprinted with permission. Jim Stanford has a longer commentary on the “battle of economic ideas” during the 2015 Canadian election, at http://www.progressive-economics.ca/2015/11/03/election-2015-and-the-battle-of-economic-ideas/ .

The post Canadian Election Shows Neoliberals CAN be Defeated appeared first on Progress in Political Economy (PPE).

Challenging Economic “Common Sense” … From Toronto to Sydney!

I am thrilled to accept the University of Sydney’s recent invitation to serve as an Honorary Professor in the Department of Political Economy. I have a long and collegial association with the Department – including delivering the second Ted Wheelwright lecture in 2009 (on the Global Financial Crisis), participating in seminars and conferences, and most recently squatting in Frank Stilwell’s office for six months in 2014 while on research leave here with my family.

The Department is a unique and irreplaceable asset in the global political economy community. It is a multidisciplinary meeting place for both scholars and activists. Its research and teaching stretches the frontiers of our understanding of world economy and society. And it attracts ambitious, committed students from around the world. I can also attest to the remarkable collegiality within the Department: its culture and practice marks the best traditions of mutual respect and diversity of analysis, yet combined with a willingness to challenge each other in the interests of formulating stronger, more convincing analyses. It will be both a great honour, and a great opportunity to further my own thinking, to be welcomed into such a fine scholarly community.

I have just settled in Sydney, having left in January my long-time position as Economist with Unifor, Canada’s largest private-sector trade union. (Unifor was formed in 2013 through a merger between the Canadian Auto Workers, where I worked since 1994, and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers unions.) The leaders and members of Unifor supported me very generously while I was there: not only providing concrete economic analysis and advice to the union, but also allowing me to play a broader role in economic policy debates in Canada and internationally. It was a difficult decision for me to leave that job (after 22 years), and I carry with me a tremendous “scrapbook” of memories of our union struggles, victories, and lessons. But the desire to do something different (not to mention the appointment of my spouse, Professor Donna Baines, to a senior position in the Department of Social Work here at the University of Sydney!) spurred the big move.

I have great hopes for transferring my work as an “activist-economist” from Toronto to Sydney. And it is already clear there will be no shortage of urgent opportunities for me to do so. A core theme in my work has been a desire to democratise economics, by expanding popular understanding (including among union members and other working people) about the ideological roots and hegemonic functions of conventional economic discourse. We need to understand that what is widely accepted as economic “common sense” (rooted in ideas about the virtue and productivity of private property, the universality of greed, and the efficiency of markets) is not scientifically based (and hence “sensible”) at all. Rather, it reflects a conscious and political effort to justify the status quo – rather than truly explaining it. I have placed great emphasis on communicating critical approaches to economics in ways that are accessible, without being simplistic or populist. The best example is through my book Economics for Everyone (now in its second printing with Pluto Books) and its associated web-based curriculum materials (all available for free at www.economicsforeveryone.com).

I have great hopes for transferring my work as an “activist-economist” from Toronto to Sydney. And it is already clear there will be no shortage of urgent opportunities for me to do so. A core theme in my work has been a desire to democratise economics, by expanding popular understanding (including among union members and other working people) about the ideological roots and hegemonic functions of conventional economic discourse. We need to understand that what is widely accepted as economic “common sense” (rooted in ideas about the virtue and productivity of private property, the universality of greed, and the efficiency of markets) is not scientifically based (and hence “sensible”) at all. Rather, it reflects a conscious and political effort to justify the status quo – rather than truly explaining it. I have placed great emphasis on communicating critical approaches to economics in ways that are accessible, without being simplistic or populist. The best example is through my book Economics for Everyone (now in its second printing with Pluto Books) and its associated web-based curriculum materials (all available for free at www.economicsforeveryone.com).

The economic and political similarities between Australia and Canada will make my transition easier, I suspect – as will Sydney’s much more appealing climate! While I am cautious about drawing too many parallels between the economic experience of the two countries, they are too obvious to overlook: both suffer from a renewed recent reliance on resource extraction as the main engine of accumulation, the associated problems of deindustrialization and environmental degradation, the distorting influence of credit-fueled speculation (in both financial assets and property), and the increasingly aggressive exercise of political influence by the concentrated interests which benefited from those regressive trends. Canada held a federal election in October 2015 (just before I left the country), in which voters threw out an unapologetic right-wing pro-extraction government, replacing it with a more moderate and balanced (but still pro-business) party. That election hasn’t remotely solved all Canada’s problems, but it was undeniably a move in the right direction – and a testament to the ability of progressive resistance campaigns to influence the course of events. With a federal election now underway in Australia, will there soon be another parallel we can draw between these two countries? I hope so.

My paying job here in Australia will be with the Australia Institute, the leading progressive research institute in the country. I will work with them as an economist, and director of a new project called the Centre for Future Work. This Centre aims to strengthen the Australia Institute’s presence and engagement in issues related to employment, labour markets, incomes, industry, and globalization. We will be publishing research reports (some quick-and-fast, some longer-term and more comprehensive), building links with trade unions and other progressive constituencies, and trying to influence the battle of economic ideas related to these topics. I am interested in partnering with political economists and other academics interested in these issues, and would welcome any inquiries in my new role (you can reach me at jim[AT]tai.org.au). The Australia Institute will be a great home for me, and I look forward to working closely with their team of progressive, entrepreneurial researchers (including a prominent alumnus of the Department of Political Economy, Dr. Richard Denniss).

I am already participating in some of the research going on in the Department of Political Economy: including Lynne Chester’s project on industry policy, and Frank Stilwell’s tireless efforts around inequality, tax policy, and related topics. And I look forward to doing much more – including guest lectures, supervision of graduate students, and other contributions.

Thank you very much to the University and the whole Department for this opportunity, and for your warm welcome to Sydney!

The post Challenging Economic “Common Sense” … From Toronto to Sydney! appeared first on Progress in Political Economy (PPE).

Bracket Creep Is A Phoney Menace

By giving a small number of relatively well-off Australians a tax cut the Treasurer has undermined revenue and helped contribute to inequality, as detailed in this post that originally appeared on New Matilda.

For someone who piously bemoans an “us versus them” mentality in political culture, Treasurer Scott Morrison certainly drove a deep wedge into the social fabric with one of the centrepieces of his budget. There are four thresholds in the personal income tax system; Morrison chose to increase one of them, supposedly to offset the insidious effects of “bracket creep.” The third threshold will be raised from $80,000 to $87,000.

Other thresholds don’t change. Taxpayers making over $80,000 will thus get a small saving ($6 per week at most). Those who make less, get nothing.

It’s not the most expensive tax cut in the budget. It will cost an estimated $800 million in the first year – barely half the $1.5 billion lost annually by cancelling the deficit repair levy on incomes over $180,000, and far less than the ultimate cost of Morrison’s company tax cuts. But it is the most transparent and easy to understand of all the budget’s tax measures. And it will spark the most gossip around the water-cooler. Who makes over $80,000 per year, anyway? And who makes less? It’s hard to imagine a more “us versus them” tax policy.

The Treasurer’s own rhetoric reinforces this schism: he says it will “reward hard working Australians,” encourage them to work overtime, take more shifts, and accept a promotion. The clear implication is that people making less than $80,000 are not interested in working more hours or taking promotions. Indeed, they aren’t even “hard working” in the Treasurer’s terms, and hence don’t merit protection from “creeping” taxes.

The Treasurer tried, but failed, to define the measure as one that benefits “average” wage-earners. Mean annual earnings for a full-time worker employed year-round are indeed near $80,000. But this does not remotely describe the typical Australian. First off, the mathematical “average” is skewed upward by super-high incomes at the top of the income ladder; the median full-time wage (received by the full-time worker in the exact middle of the distribution) is $10,000 lower than the average, and well below the threshold. Likewise, women (even those employed full-time year-round) earn $10,000 less than the mathematical mean.

Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison delivering his first budget, in 2016.

But the bigger problem is that a shrinking share of Australians have full-time permanent jobs to start with. Part-time work now accounts for almost one in three jobs – the highest on record. And labour hire, temporary contract, and other forms of precarious work are increasingly the norm. Very few of those workers earn anywhere near $80,000. At most about one in four Australian workers (and perhaps 15 per cent of all tax-filers) will get the full $6 per week saving.

The whole concept of “bracket creep” is itself as misleading as Morrison’s maths. He says taxpayers are “pushed” into higher tax brackets by rising incomes, constituting a punitive and underhanded tax grab. But this description merits some careful second thought.

There are two different reasons why a worker’s income might rise. One is pure inflation, experienced across all wages and prices. In that case, nothing “real” changes, and a higher tax rate might seem unfair (although we should remember that the cost of many government programs also grows with inflation, and someone has to pay for that).

Alternatively, it might be changes in a worker’s real income that qualify them for the next bracket. If they worked more hours or took a promotion (as the Treasurer urges), then their real income rises, and so does their tax. That’s not bracket creep, and there’s nothing “underhanded” about it. In fact, that is the whole point of a personal income tax system in which tax rates depend on income.

Moral panic over bracket creep is all the more ironic given the unprecedented stagnation in Australian wages, reflecting sustained weakness in the job market. Average weekly earnings in the private sector are growing at their slowest pace in history: under 1 per cent per year (slower than inflation). The budget itself acknowledged this is badly hurting Commonwealth revenues. With wages going nowhere fast, this is hardly the time in history to make a mountain out of a bracket creep molehill.

If the government truly wanted to prevent inflation from distorting taxes, it could simply index all parameters in the tax code to consumer prices (as other countries, like the U.S. and Canada, have done). Then all thresholds, not just the one cherry-picked by Morrison, would rise 1.3 per cent this year, the same as year-over-year inflation. But that would depoliticise the whole process, hardly acceptable in a year when every single clause of the budget is focused on getting the government re-elected. So Morrison picked one politically-potent threshold, lifted it seven times faster than inflation, and left everyone else to get “creeped.”

Previous ad-hoc increases to thresholds have lifted them far faster than inflation. In fact, with this latest increase, the third tax threshold will have risen twice as much as inflation since 2003. Combined with rate reductions also targeted at top brackets during that time, government revenues have been undermined badly, and the upward redistribution of after-tax income has been exacerbated.

In short, the politics of Morrison’s over/under game are hard to understand. He will deliver a tiny benefit to less than one in four employed workers, and barely one in seven tax-filers. Most Australians won’t get a cent. But the economics are even worse. His divisive and false anti-tax narrative undermines the long-run stability of the government’s revenue base, damages public services, and reinforces inequality.

***

This post was originally posted on New Matilda (11 May 2016).

The post Bracket Creep Is A Phoney Menace appeared first on Progress in Political Economy (PPE).

Six Counterpoints about Australian Public Debt

In the lead-up to today’s pre-election Commonwealth budget, much has been written about the need to quickly eliminate the government’s deficit, and reduce its accumulated debt. The standard shibboleths are invoked liberally: government must face hard truths and learn to live within its means; government must balance its budget (just like households do); debt-raters will punish us for our profligacy; and more. Pumping up fear of government debt is always an essential step in preparing the public to accept cutbacks in essential public services. And with Australians heading to the polls, the tough-love imagery serves another function: instilling fear that a change in government, at such a fragile time, would threaten the “stability” of Australia’s economy.

However, this well-worn line of rhetoric will fit uncomfortably for the Coalition government, given its indecisive and contradictory approach to fiscal policy while in office. The deficit has gotten bigger, not smaller, on their watch, despite the destructive and unnecessary cutbacks in public services imposed in their first budget. Their response to Australia’s fiscal and economic problems has consisted mostly of floating one half-formed trial balloon after another (from raising the GST to transferring income tax powers to the states to cutting corporate taxes), with no systematic analysis or framework. And their ideological desire to invoke a phony debt “crisis” as an excuse for ratcheting down spending will conflict with another, more immediate priority: throwing around new money (or at least announcements of new money), especially in marginal electorates, in hopes of buying their way back into office.

In short, the politics of debt and deficits will be both intense and complicated in the coming weeks. To help innoculate Australians against this hysteria, here are six important facts about public debt, what it is – and what it isn’t.

1. Australia’s public debt is relatively small

Despite annual deficits incurred since the GFC, Australia’s accumulated government debt is still small by international standards. Debt can be measured on a gross or net basis; gross debt counts total outstanding borrowing, while net debt deducts the value of financial assets which the government also possesses. Gross debt for all levels of government equaled 44% of Australian GDP at the end of 2015 (according to the OECD). That was the 5th lowest indebtedness of any of the 34 OECD countries (see table below), equal to about one-third the average level experienced across the OECD. Moreover, despite recent deficits, the growth of debt in Australia was considerably slower than in most other OECD countries. Of course, having low debt in and of itself does not justify increasing it. But given the universal fiscal challenges that have faced industrial countries since the GFC, Australia’s debt challenge is both unsurprising and relatively mild.

Australia’s Debt in International Context:

General Government (all levels) Gross Financial Liabilities (%GDP)

2015

10-yr. Change

Australia

44.2%

+22.4 pts

U.S.

110.6%

+43.7 pts

Japan

229.2%

+59.7 pts

France

120.1%

+38.3 pts

Germany

78.5%

+8.1 pts

Italy

160.7%

+41.8 pts

U.K.

116.4%

+60.3 pts

Canada

94.8%

+19.0 pts

OECD Average

115.2%

+36.3 pts

Source: Author’s calculations from OECD Economic Outlook #98, Nov.2015.

2. A government debt is matched by an asset

Australians aren’t “poorer” because their government accumulates a debt. Any rise in government debt is mirrored by an increase in some offsetting asset. This is true in both accounting terms, and in real economic terms. For example, government typically issues a bond (or some other financial instrument) to finance a deficit. But that bond also constitutes an asset in the investment portfolio of whoever lent the government money. Most Australian government debt is owned by Australians. In fact, investors increasingly appreciate the opportunity to invest in government bonds, because they are safer than other assets at a time of financial uncertainty. (That investor interest is one reason interest rates on government debt are so low.) So government debt translates into someone else’s wealth – usually someone in Australia.

This match between liabilities and assets is also visible in concrete economic terms – especially when new debt is issued to construct a real, long-lasting capital asset (like a road, a transit system, a school, or a hospital). In this case, the matching asset is owned by government itself, and so its own net worth won’t change much at all: it takes on a new debt, but also has a new asset. For budgetary purposes, the government must account for the gradual wear-and-tear of that asset (called depreciation), which appears as a cost item on the budget. But it hasn’t “lost” the money it raised through the new debt: it invested it, and that investment carries both financial and social value.

3. Other sectors of society borrow much more than government

Tired rhetoric about how governments need to act “more like households” is especially ironic, given that households are by far the most indebted sector in Australian society. Household net debts equal close to 125% of GDP – or around 4 times the net debt of government (all levels), according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. It is factually wrong to claim that “households balance their budgets,” and therefore governments must do the same. Households borrow regularly – and thanks to overinflated housing prices and stagnant wages, that borrowing is growing rapidly. The same is true of business: net debts of non-financial corporations are more than twice the net debt of government (see chart).

In fact, it is quite rational for households and businesses to borrow, when needed to fund purchase of long-run productive assets (like a house or a car for consumers, or a factory or new technology for a business). Business leaders know that rational, prudent borrowing will enhance the profitability of a corporation. Indeed, any CEO who said paying off all company debt was the top priority of the firm would be chased from office by directors and shareholders (who would understand the pledge was irrational and superstitious). Following exactly the same logic, government debt can be rational and productive – especially (but not only) when it is associated with the acquisition of long-run productive assets (like infrastructure). Close to two-thirds of the Commonwealth government’s 2015/16 deficit (projected to be $36 billion) is associated with capital spending, including $11 billion in capital transfers to lower levels of government and $12 billion in net investment in Commonwealth non-financial assets. Contrary to the rhetoric, Australians do largely cover the cost of current public services with their current tax payments. Government borrowing is primarily required to fund capital spending.

4. Interest rates are low, and falling

The cost of public borrowing has fallen dramatically as a result of the decline in Australian and global interest rates since the GFC (see chart). Indeed, the two factors are connected: large government deficits resulted primarily from underlying economic weakness (this is true in Australia, like elsewhere in the industrialized world), which in turn brought about low interest rates (via both central banks and private financial markets). These very low interest rates mean that the cost-benefit decision associated with any new government borrowing has been fundamentally altered, in favour of borrowing.

Current interest rates are likely to stay low for many years to come, given the continuing failure of the global economy to regain consistent momentum, the slowdown in China, and other factors. (In fact, it is possible that the Reserve Bank of Australia may soon cut its interest rate further, below its current record-low 2% level, due to weak growth and signs of deflation here in Australia.) Ten-year Commonwealth bonds can presently be floated to private investors for little more than 2% interest (close to zero in real after-inflation terms). If government can borrow for what is effectively zero interest, and put that money to work in the real economy doing useful things (including both infrastructure and public services), then it is irrational to let old-fashioned balanced-budget mythology stand in the way.

Even if current interest rates do not fall any further, the average effective interest rate paid on overall public debt will continue to fall for years to come. The current average effective rate paid on Commonwealth debt (about 3.5% last year) reflects the weighted average paid on all maturities of debt. As past debts come due, they are refinanced at now-much-lower interest rates (those prevailing on new issues of bonds). That will pull down the average weighted interest rate for several years into the future – even if the rate on new issues stabilizes or increases somewhat. Consider that new ten-year bonds can be issued for less than half the interest rate paid a decade ago. The refinancing of those bonds will generate enormous future interest savings for government (equivalent to home-owners who re-mortgage their homes to benefit from the decline in household lending rates).

This is why the economic burden of public debt servicing is not growing, even though the debt is. Government budget projections forecast debt service remaining at between 0.9 and 1.0% of GDP for the next 5 years, with the effect of rising debt offset by falling interest rates. And those government projections likely overestimate true interest costs (partly for political reasons). For example, the December 2015 MYEFO update assumes a significant increase in interest rates in the coming year (its near-term interest rate assumption was 0.3 points higher than the assumption used in last year’s budget); ongoing global and domestic economic weakness makes that highly unlikely.

5. The debt/GDP ratio is a more meaningful fiscal constraint than a balanced budget

Fear-mongers think that by talking about public debt in “big numbers,” the fright value of their dire forecasts can be magnified accordingly. But all macroeconomic aggregates are measured in big numbers. And what’s more important than the absolute size of debt, is the government’s capacity to service that debt. That, in turn, depends on the flow of government revenues, which in turn is driven primarily by overall economic growth. That’s why economists prefer to evaluate public debt relative to GDP (called the “debt ratio”). Even this ratio can overstate the real burden of debt, in times (like now) when interest rates are low and falling.

Avoiding a lasting, uncontrolled rise in the debt/GDP ratio is a more meaningful fiscal constraint on government, than trying to balance a budget in any particular year. Economists do not agree on a maximum “acceptable” limit for that ratio. But most agree it cannot rise forever. (Some economists argue that there is no limit on a government’s ability to issue sovereign debt denominated in its own currency, and the recent experience of countries like Japan – whose debt ratio is five times Australia’s – is consistent with that view.)

At any rate, Australia is far away from any feasible “ceiling” on public debt relative to GDP. And remember, like any ratio, the debt/GDP ratio has both a numerator and denominator: growing the denominator is as effective as shrinking the numerator, if the goal is reducing the value of the combined ratio. In this regard, the stagnation in Australia’s nominal GDP in recent years has been more damaging to the trajectory of the debt ratio, as has the addition of debt through continued deficits. The government’s policy focus should be on expanding economic activity (and the jobs and incomes that go with it), rather than suppressing the deficit with austerity measures (which have the unintended consequence of undermining growth and hence the economy’s ability to service a given amount of debt).

6. The government can incur moderate deficits every year, yet still stabilize its debt burden

A related and under-appreciated countervailing argument is to note that government can run a medium-sized deficit on an ongoing basis, and yet experience no increase in the debt/GDP ratio at all – so long as the economy is progressing at a normal pace. A deficit adds to the numerator of the ratio, while economic growth expands the denominator. So long as both are expanding at roughly the same rate, the ratio will not be changed. (Our reference to economic expansion envisions more jobs and incomes across the economy, including in the public sector, and with due attention to the need for environmental sustainability.) This basic arithmetic provides government with an additional degree of maneuverability in financing essential services and investments, without unduly increasing the debt ratio.

A simple numerical example helps to illustrate the point in Australia’s context. A healthy economy should be expanding by at least 5-6 percent per year in nominal terms: divided roughly equally between inflation (given the RBA’s 2-3 percent inflation target) and greater output of real goods and services (driven by both population and productivity). The Commonwealth’s current net debt ratio is slightly below 20 percent of GDP. With a healthy economic expansion, the government could incur an annual deficit of 1-1.25 percent of GDP (or close to $20 billion per year) but still stabilize the debt ratio below that 20 percent benchmark. And there is nothing magical about a 20% debt ratio; if Australians were willing to tolerate a larger steady-state debt ratio, then the size of this annual permissible deficit would be correspondingly higher. All this merely reinforces the need for government to focus on supporting job-creation and incomes, not balancing its budget – and confirms that ample fiscal space is indeed available for the Commonwealth to fund public services and infrastructure spending (with the fringe benefit of reinforcing strong job creation that should be their top priority).

The post Six Counterpoints about Australian Public Debt appeared first on Progress in Political Economy (PPE).

Elizabeth Humphrys, ‘Australia under the Accord (1983-1996)’

Elizabeth Humphrys (University of Technology Sydney), 'Australia under the Accord (1983-1996): Simultaneously Deepening Corporatism and Advancing Neoliberalism'

This is the fifth seminar in the Semester 1 series of 2016 organised by the Department of Political Economy at the University of Sydney.

Date and Location:

Note the time change!

5 May 2016, Darlington Centre Boardroom, 4:30pm – 6.00pm

All welcome!

Monday, 15 February 2016 - 11:17am

Always liked that Turnbull fellow. Won't hear a word said against him.

I'm choosing to take this as a sign that things are looking up; that it's no longer sufficient to be a plutocratic ideologue and class warrior to have a hand in Australian public policy.

On the other side of the house, even Shorten appears to have located his spine, and is advocating the decades-overdue sunsetting of the parasitic speculator's best friend, negative gearing. In addition to the hitherto inconceivable possibility of a soft landing to the property bubble, Australia may be catching on to the spirit of democratic renewal that has made possible the rise to prominence of people like Sanders and Corbyn (not to mention, in very different circumstances, Podemos and pre-capitulation Syriza).

Good news for everybody who hasn't thrown in their lot with the crazies. Commiserations to the former Member for Tony Abbott.