Economic policy

Industrial Policy in Turkey: Rise, Retreat and Return – review

In Industrial Policy in Turkey: Rise, Retreat and Return, Mina Toksoz, Mustafa Kutlay and William Hale analyse Turkey’s industrial policy over the past century, highlighting the interplay of global paradigms, macroeconomic stability and domestic institutional contexts. The book offers a timely analyses of industrial policy’s past and possible future trajectories, though it stops short of interrogating exactly how cultural, social, political and economic factors shape state-business relations and bureaucracy, writes M Kerem Coban.

Industrial Policy in Turkey: Rise, Retreat and Return. Edinburgh University Press. 2023.

Is industrial policy back? The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, or the 2016 UK industrial policy are only two contemporary examples. These policies seek to address value chain bottlenecks, as well as the question of how to “take back control” in manufacturing and key sectors, along with concerns about gaining or sustaining economic edge and autonomy

Is industrial policy back? The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, or the 2016 UK industrial policy are only two contemporary examples. These policies seek to address value chain bottlenecks, as well as the question of how to “take back control” in manufacturing and key sectors, along with concerns about gaining or sustaining economic edge and autonomy

In this context, the Turkish experience is illustrative for making sense of the trajectory of industrial policy in a major developing country. Mina Toksoz, Mustafa Kutlay and William Hale examine the evolution of industrial policy in Turkey. They present an accessible, detailed account of the trajectory and evolution of the policy since the establishment of the Republic, which argues that we had better study “the conditions under which state intervention works, rather than whether the state should intervene in the economy” (26, emphasis in original).

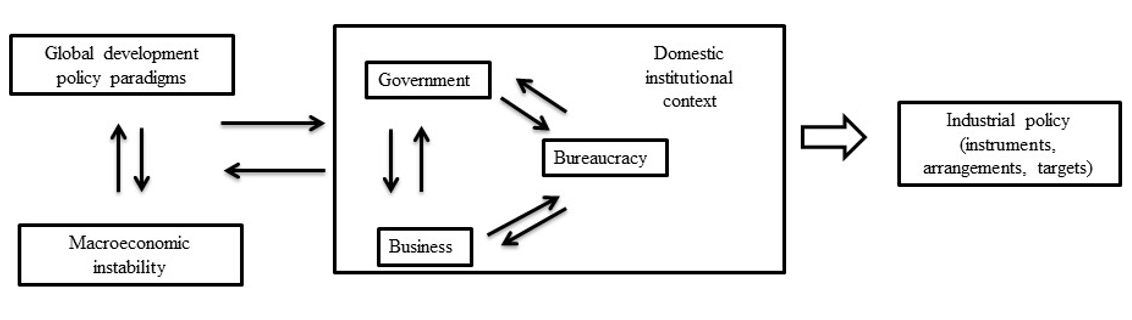

[The authors] suggest that effective industrial policy is the outcome of the interaction between global development policy paradigms, macroeconomic (in)stability, and the domestic institutional context.

The book is divided into five chapters. Chapter One discusses the political economy of industrial policy and sets out an analytical framework. The authors assert that analyses should go beyond dichotomies (eg, horizontal vs. vertical policies; export-led vs. import-substituting industrialisation) and that a broader understanding requires identifying the factors and conditions of effective industrial policy. They suggest that effective industrial policy is the outcome of the interaction between global development policy paradigms, macroeconomic (in)stability, and the domestic institutional context. Global development policy paradigms evolved from étatism of the 1930s, import-substituting industrialisation in the 1960s and the 1970s, neoliberalism of the 1980s, and the return of industrial policy after the 2008 Financial Crisis. Macroeconomic (in)stability drives (un)certainty regarding economic policies and instruments and the trajectory of economy, which, in turn, regulates investment decisions. Finally, the domestic institutional context concerns how state-society, or state-business, relations are structured, whether the state capacity is sufficient to resolve conflicts, discipline and coordinate actor behaviour, and whether bureaucracy has capabilities to formulate and implement policies. Figure 1 seeks to summarise the main argument of the book.

Figure 1: Flow chart summarising the book’s main argument. Source: M Kerem Coban.

Figure 1: Flow chart summarising the book’s main argument. Source: M Kerem Coban.

Chapter Two focuses on the longue durée between 1923 and 1980. From the ashes of incessant wars that ruined the already unsophisticated infrastructure and demographic challenge, the new Republic had to build a new nation. Yet the rise of the state interventionist era in the 1930s drove policymakers towards the first industrialisation plan and the opening of many industrial sites across the country. When the Democrat Party assumed power, the interventionist, planning-based industrial policy was scrutinised for liberalisation that even included state-owned enterprises to be released to set up their own prices (73).

At the same time, business was encouraged to invest. For example, the fruits of these included Otosan or BOSSA (75). Between 1960 and 1980, the authors underline the second planning period with the establishment of the State Planning Organisation (SPO). SPO boosted bureaucratic and planning capacity and capabilities for disciplined, systematic industrial policy during the era of import-substitution.

Between 1980 and 2000 […] Turkey shifted to export-led growth and liberalised trade and financial flows. These shifts had profound implications for bureaucracy

The third chapter examines demoted industrial policy between 1980 and 2000 when Turkey shifted to export-led growth and liberalised trade and financial flows. These shifts had profound implications for bureaucracy: SPO was sidelined, parallel bureaucratic networks of Ozal were implanted with the opening of new offices or agencies. Consequently, the role of state became less coherent, as political uncertainty driven by unstable coalitions eroded the market-shaping role of the state. The financial sector did not help industrial policy, since banks were dominantly financing chronic budget deficits during a period of high inflation (111). What is more, business, including Islamic conservative SMEs in Anatolia, reduced or ignored investments in manufacturing given the clientelist state-business relations that incentivised construction, real-estate development (115), emphasis in original). Finally, the external conditions were not disciplinary: accession to the Customs Union with the European Union and the World Trade Organization ruled out export support and import restricting measures, among other trade regulatory instruments.

The fourth chapter claims that industrial policy retreated between 2001 and 2009. The first years of this period was marked by political instability and a local systemic banking crisis and its resolution, and Justice and Development Party (AKP in Turkish) assumed power. During this period, industrial policy was dominated by institutionalisation of the regulatory state and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, the establishment of autonomous regulatory agencies and are structured banking sector. While the regulatory capacity of the state increased, privatisation and the regulation of the market were highly politicised. For example, “a major cycle of gas privatisation saw ‘politically connected persons’ winning fifteen out of nineteen metropolitan centres and serving 76 percent of the population” (161). In such a politically compromised setting, which was accompanied by the institutionalisation of the capital inflow-dependent credit-led growth model that prioritised “rent-thick” sectors, industrial policy could not flourish.

While the regulatory capacity of the state increased, privatisation and the regulation of the market were highly politicised.

The fifth chapter locates the policy within the global ideational and political economic context that marks the return of industrial policy in various forms. In line with policy documents such as the 11th Development Plan, horizontal measures, private and public R&D spending on high-tech initiatives, electric vehicle manufacturing attempt, and most notably the advancements in defence sector have constituted the revival of industrial policy. At the same time, the authors point to several challenges such as eroded academic research and quality and a lack of investment in ICT skills. Additionally, R&D subsidies or other industrial policy measures require thorough performance criteria and measurement to discipline actor behaviour and regulate the incentive structures.

Industrial Policy in Turkey is a timely contribution to the current debate. Its historical account and analysis of current policies, instruments, and the potential trajectory of industrial policy are its main strengths. Still, there are several caveats. First, the book’s framework is not systematic, which causes some confusion. For example, the book does not demonstrate a convincing link between the role and impact of autonomous agencies on industrial policy. Second, the book leaves the reader with more questions than answers, one of which relates to the effect of bureaucratic fragmentation in shaping industrial policy. Another is around the implications of state-business for bureaucracy, and consequently, industrial policy.

The book leaves the reader with more questions than answers, one of which relates to the effect of bureaucratic fragmentation in shaping industrial policy.

Third, the trajectory of industrial policy cannot be considered independently from the shifts in growth models. Yet the fact these shifts occur because the country depends on hard currency earnings for capital accumulation and to finance consumption and investments: Turkey either relies on capital flows or export earnings, in addition to tourism and (un)recorded (illicit) flows. Pendulums between these channels imply that the country cannot design and implement disciplined, systematic industrial policy. Put differently, there are macroeconomic and financial structural impediments against generating hard currency earnings. Industrial policy is one of the remedies, however, the macroeconomic and structural transformative consequences of the latest episode of emphasis on industrial policy and the export-driven growth experiment in Turkey are yet to be seen.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the book tends to relegate a core problem of coordination, long-term policy design and implementation to “governance issues”. Deeper cultural, social, political and economic factors determine the clientelist state-business relations and their effect on bureaucracy and bureaucratic autonomy. Such deeper ties have been masked by instrumentalised “democratisation reforms” or higher economic growth rates in the previous years. In this context, is the more critical problem the purposefully immobilised or challenged infrastructural power to coordinate societal actors? If that is true, then should we make interdisciplinary attempts to identify this problem’s core determinants?

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Chongsiri Chaitongngam on Shutterstock.

Debt, Deficits, and Warranted Money

by Brian Czech

Concern over mushrooming debt is growing. Click on the image to see the casino-like tumbling of national debt “clocks.” (US Debt Clock)

If you recognize the damages done by a bloating economy, you’ll be alarmed by the global GDP meter, which hit the existentially menacing threshold of $100 trillion in 2022. If that doesn’t give you a dose of distress, try the global debt clock. Then, for a dizzying dose indeed, check the casino-like combination of debt and GDP maintained by “US Debt Clock.”

Almost all readers, bearish and bullish alike, can sense the unsustainability of skyrocketing debt. Even wild-eyed growthists, who see no problem in a perpetually growing GDP, can’t abide a perpetually growing debt. Yet very few critics of debt can articulate, with economic fundamentals, why such debt is so unsustainable.

Sadly absent from the discussion of debt is the ecological underpinnings of money. As long as these underpinnings remain overlooked, the money lenders will be overbooked. Deficit spending will rule the day, and global debt will continue rocketing into the stratosphere, heading for the sun like a pecuniary phoenix.

Let’s have a closer look at the debt problem, with a focus on global and U.S. scenarios. We’ll consider the relationship of debt to deficit spending, along with inflation. Finally, we’ll bring in the ecological basis of money, and hope our policymakers grasp and apply it, lest our money supply—not to mention the planet—turn to ashes.

Deficits and Debt: Global and U.S.

As global GDP was ramping up to the planetarily punishing $100 trillion level, global debt was already surpassing $300 trillion. It reached that dubious distinction in 2021, just one year after reaching the previous record of $226 trillion. It has since come down from the peak, but still stands around $238 billion, and the reduction is surely short-lived.

The majority of global debt is private, especially corporate but significantly household debt as well. Public debt—money owed by governments—makes up about a third.

In the USA, those proportions are roughly reversed. From the county commission to Capitol Hill, American politicians have ambitions that far exceed government coffers. When they’re not spending money to “stimulate the economy,” they’re trying to spend their way out of the social and environmental problems caused by an overstimulated economy. They spend money they don’t have; that’s deficit spending and it adds to the public debt.

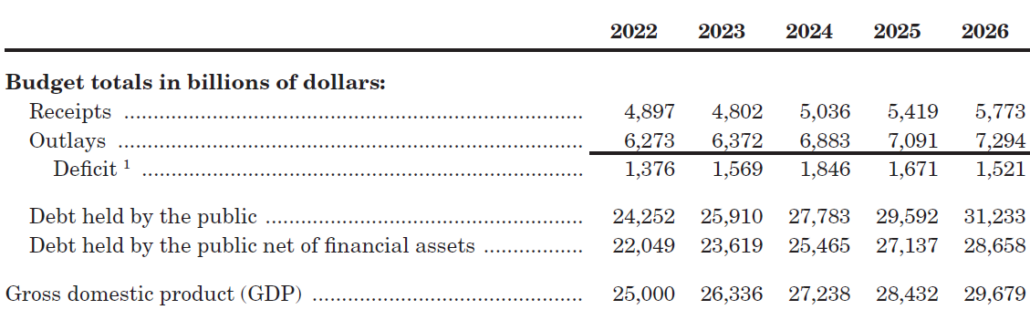

Deficit spending is a way of political life in the U.S. Government. (Image snipped from 2024 Budget of the U.S. Government.)

At this point in fiscal year 2024 (October 1, 2023 through September 30, 2024), the U.S. government deficit stands at roughly $532 billion, contributing another two percent to the federal debt of $26 trillion. The deficit may lessen as taxes are collected in the coming months, but then it will shoot back up for the remainder of the year. Even the figures provided by the Administration (probably rosy figures) acknowledge that the deficit is expected to be a whopping $1.8 trillion by the end of fiscal 2024. That’s nearly seven percent of the 2023 GDP ($26 trillion).

The USA is particularly relevant to the global debt; its debt is bigger than any other. In fact, U.S. entities—government and private combined—carry a debt burden nearly the size of the global economy!

Only Japan and China have joined the USA in the club of over $10 trillion government debt. France, Italy, the UK, Germany, India, Canada, Spain, and Brazil all have debts exceeding a trillion dollars.

In terms of relative debt (ratio of debt to GDP), Japan is at the top of the list at 255 percent. Greece, Singapore, Italy, Bhutan, and the USA (123 percent) round out the top six.

Deficit Spending: Getting Dumb and Dumber?

Deficit spending has a long history in American policy. The fiscal exigencies of war have triggered deep deficits, with World War II as the classic case. But huge deficits were already incurred during the Great Depression, coinciding with the influence of the British economist John Maynard Keynes. In the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes prescribed a liberal dose of deficit spending to spur the western economies out of recession.

But Keynes never said to go hog wild, much less stay that way. So, for many decades now Americans have heard the debate between fiscal conservatives and “deficit-spending liberals.” They both want growth, but conservatives think a persistent deficit and ballooning debt is more burden than boon for GDP. They typically only abide a big debt for hawkish military purposes. Otherwise they’re “budget hawks.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are you sure about MMT? (Wikipedia)

Inveterate deficit spenders, on the other hand, think they can stimulate the economy by picking the winners and funding the right programs.

Into this old debate comes “modern monetary theory,” centered around the idea that deficit spending is generally fine, and policymakers needn’t worry too much about a growing debt, as long as the economy is also growing. Beyond that, “MMT” seems to mean many things to many people and has polarized the economics community. Even pollyannish growthists like Paul Krugman find MMT “obviously indefensible.” Another growthist (aren’t they all?) at the dark-monied Mercatus Center calls MMT “a bizarre, illogical, convoluted way of thinking.”

MMT does, however, provide some political cover for politicians hunting pork. The late King of Pork, Senator Robert Byrd, would have championed MMT all the way to the bottom line. But MMT has persuaded some presumably more fiscally innocent members of Congress, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Senator Bernie Sanders, and even John Yarmuth, past chair of the House Budget Committee.

In any event, it’s hard to tell what’s so “modern” about MMT. It has a few new wrinkles—it picks them up as it goes along—but basically it’s just another phase of Keynesian thought on deficit spending. And, as President Nixon said a half century ago, “We’re all Keynesians now.” He could have added, “We’re all growthists, too!”

And so, the first subheading that appears in this year’s federal budget (page 5) is: “GROWING THE ECONOMY FROM THE BOTTOM UP AND MIDDLE OUT.” We could add: “WITH A SHOT OF DEFICIT STEROIDS.”

Money Supplies: Warranted vs. Inflated

In 1939, one Sir Roy Forbes Harrod wrote “An Essay in Dynamic Theory,” published in the stately Economic Journal. Until then, little had been theorized about the process of economic growth, and rarely with such nuance. Harrod’s approach is considered a leading precedent of growth theory.

Harrod spent much of his 20-page essay contemplating three kinds of growth rates: warranted, natural, and actual. Our charge here is not to dive deeply into Harrod’s thoughts on growth rates, but to see where they take us on debt and inflation. In particular, I propose we have three levels of money supply: warranted, real, and nominal.

Economists are familiar with the latter two. The real money supply has been adjusted for inflation, typically by pegging to a particular year. The nominal supply is expressed in terms of face value in real time. For example, $1.38 trillion today—the nominal money supply of a hypothetical country—is only one trillion real dollars, if we’re pegging to 2010.

It’s the “warranted” supply I’m proposing here. The concept stems from the trophic theory of money, which is that money originates via the agricultural surplus at the base of the economy. Not agricultural surplus in the sense of grain going to waste in the fields, but surplus in the sense that one farmer can grow enough to feed many people.

It is that surplus—more broadly, a food surplus but for all practical purposes the agricultural surplus—that frees the hands for the division of labor. The division of labor, in turn, allows for the exchanging of goods and services. All this calls for an efficient means of exchange, store of value, and unit of account: money, in other words.

Money is warranted, then, by the division of labor flowing from agricultural surplus.

Money didn’t just originate historically via agricultural surplus—as it did in Mesopotamia, Lydia, and the Yellow River Basin of China—it originates each year in the breadbaskets of the world. Actually it originates twice a year as these breadbaskets are found in Northern and Southern Hemispheres. North America (prairies and California), China, Southeast Asia, Brazil, and Chile come to mind, plus of course the contested confluence of political Europe and Russia, centered in Ukraine.

You might say money gets “printed” into circulation with each perennial pulse of wheat, rice, corn, oats, barley, and soybeans. Massive harvests free billions of hands for a spectacular division of labor and the exchanging of trillions of dollars of warranted money. Lenin was right on the money (so to speak) when he referred to grain as “the currency of currencies.”

Wheat combine “printing money” in North Dakota. (Flickr)

Think about it: How would money remain relevant in a world of agricultural collapse? Everyone would be occupied with growing, gathering, catching, or commandeering their own food. No one would be producing other types of goods and services, much less bringing them to market. Money would be worthless; it wouldn’t be warranted.

Not so with the collapse of massage services, NASCAR, hip hop, or even Taylor Swift. Nor with the disappearance of boats, guns, electronics, fur coats, or perfumes. A thousand container ships of manufactured dreck could be dumped in the Panama Canal, never to be seen or sold again, and the economy would persist. Plenty of other goods and services would remain. Money would still be meaningful, relevant, and valuable.

It’s an entirely different story with the world’s soy, root crops, poultry, livestock, finfish, and, above all, grain. Burn those up like some omnipotent, omnipresent Putin, and watch the economy come tumbling down in days.

That is why, in a fundamental sense, it is agricultural surplus that “prints” money into circulation. The warranted money supply, then, is that which reflects the amount of agricultural surplus. Lots of surplus warrants lots of money; little surplus warrants little money.

The trophic theory of money doesn’t explain every possible aspect of monetary economics, at least not directly. For example, how big a role do livestock and fish play in food surplus and therefore warranted money? What’s the linkage of food surplus to energy inputs? What about other natural resources at the trophic base of the economy such as heavy fiber and timber? (It takes clothing and shelter to subsist, not just food.)

The trophic theory of money generates plenty of research questions, but it provides plenty of insight as is. Take inflation, for example. That’s when the nominal money supply exceeds the warranted supply.

Limits to Warranted Money

While it is helpful to think of money as being “printed” into circulation with agricultural surplus, it is even more helpful to think of money being “footprinted” into circulation. There’s no way to produce an agricultural surplus—or a warranted money supply—without a heavy ecological footprint. Not for a population of eight billion people.

It takes a lot of inputs to grow a lot of food, so the ecological footprint of agriculture reaches far beyond the field. (Flickr)

Each parcel on the planet has a biological capacity. So, given limits to agricultural efficiency, we know that the ecological footprint of agriculture can only reach so far (or sink so deep, if you prefer). Then it exceeds the biological capacity, agricultural surplus plunges, and the warranted money supply drops like a shot.

The pre-existing, nominal money supply remains, but to what avail? With no agricultural surplus, businesses big and small disappear—banks, too—and the government defaults. All but the most civilized (or uncivilized but ethical?) polities descend into some sort of chaos. The nominal money supply might still be in the trillions of dollars, but it’s neither warranted nor real. It’s like the gold supply of King Midas. It’s hyperinflated, not because of an “overheated” economy and the pull of demand; quite the opposite. It’s devalued by “cost-push” inflation, the relentless price increases due to diminished stocks of natural capital.

What the Fed Needs Now

The Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, Budget Committee(s), World Bank, and all the other fiscal, monetary, and financial institutions need a reality check in the form of basic and applied ecology. They need to learn especially about the concepts of trophic levels and carrying capacity. Otherwise they won’t be able to sufficiently connect the dots among deficits, debt, and cost-push inflation.

Right now, the Fed’s approach to curbing inflation is the ham-handed raising of interest rates. But raising interest rates only works (sometimes) for the “demand-pull” form of inflation, where prices rise due to an increasing propensity to consume, or due to an injection of nominal money (as with deficit spending). It’s no remedy for cost-push inflation stemming from limits to growth in the real economy.

The Federal Reserve needs ecological training to manage inflation. (Wikipedia)

I’m not saying these accomplished folks—geniuses in other ways—have no sense of economic capacity. They most certainly do; they monitor and talk about it all the time. Unfortunately, they have essentially no knowledge of ecological capacity, so their notions of economic capacity are flawed. They tend to think of capacity in terms of financial capital, labor, manufacturing facilities, infrastructure, and new technology. It’s reminiscent of Herman Daly’s lament about focusing on the kitchen and the cook, with little thought to the ingredients.

When is the last time you heard a Jerome Powell or a Janet Yellen utter a word like “soil” or “water” or “forest” or “fishery”? Yet those are the stocks of natural capital at the very base—the trophic base—of the economy they preside over. They should be intent upon conserving those stocks, if not for purposes of long-term human wellbeing (which would be nice), then at least for purposes of fighting inflation!

Brian Czech is CASSE’s Executive Director.

The post Debt, Deficits, and Warranted Money appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Positing Job Guarantee Antecedents – Part 1 of 2

By John Haly and Dr. Martha Knox-Haly, originally published at Auswakeup Media.

Any monetary sovereign government can address unemployment through social and political means, giving the working class a functional financial safety net. What stands in the way, however, is the political establishment’s lack of will and refusal to renounce neo-liberal ideology, which uses the unemployed as a bargaining chip for the capitalist class. In this two-part analysis, the requirements for genuine full employment are reviewed.

The concerns about getting a job, keeping or leaving a job, and the anxiety of finding another generate concerns in the working class. This is not merely because of the issue of mismatches between skills and job vacancies. Skills mismatch or underutilization (e.g., an engineering graduate working as a waiter) is not as well measured in the USA, as it is in Canada, Australia, and the EU (Sullivan, 2014; Ch 4 Pg 49-51). Lack of access to employment is an additional problem because, as basic statistics consistently show, there are more unemployed people than vacancies. Federal job guarantees are proposed by economists who hope in vain that the political class will minimally support full employment policies. The political class seldom do and haven’t in Australia in over half a decade.

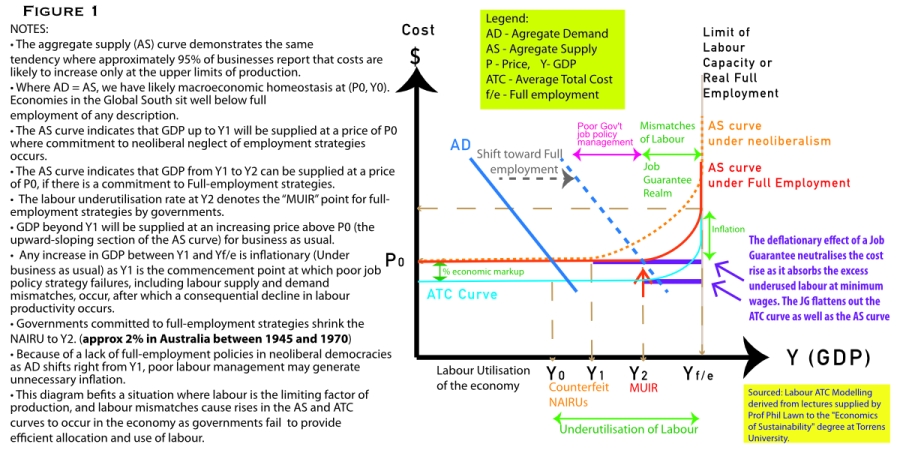

There are numerous solutions to achieve full employment, but confusion about how to define “full”. Although Australia had 3.7% unemployment late in 2023, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) claims we have gone beyond “full” employment (Grudnoff, 2023). Neo-classical economists define “full” as the moment before a “NAIRU” inflation point (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2023). Some economic disciplines have long criticised the NAIRU’s description (Sawyer, 1997). Other post-Keynesian economists have proposed that to bridge the gap between a “NAIRU” version of “full employment” and real full employment. We should look to a Federal Job Guarantee to address any inflation risks that arise when labour is fully consumed (Mitchell, 2020). This employs the “non-accelerating inflation buffer employment ratio” – NAIBER (Madi, 2019). This is a systemic idea for an internal inflation control mechanism conceived of by economists Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell, amongst others (Mosler, 1997) (Mitchell, 2016).

The counterfeit NAIRU

To address this issue, some points need to be made about the NAIRU. The RBA’s conception of the NAIRU, which proposes a trade-off between inflation and unemployment is one representation (Hutchens, 2023). This will be referred to as the “counterfeit NAIRU”. It presumes that monetary policy can by itself alleviate cost-push inflation (which current global inflation most certainly is). Under its own precepts, monetary policy is only presumed capable of dealing with demand-pull inflation (Grothe, Weber, & Nikiforos, 2024). My second representation is a “legitimate/efficient NAIRU” (to the extent that NAIRU is legitimate) this is refferred to as a “Mismatched Unemployment Inflationary Rate” (MUIR). The phrase “legitimate NAIRU” is applied with caution about labour mismatch-induced inflation, when labour is the economy’s limiting factor of production. MUIR is the point at which mismatches between skills and job vacancies would generate inflationary effects in the absence of a federal job guarantee (Mitchell, 2021). The difference between these approaches is that the NAIRU uses unemployed humans as a buffer stock, whereas a job guarantee uses employed humans as a buffer stock (Sanderson, 2019). The MUIR is the point at which other barriers to unemployment are eliminated. No Western government has made any serious effort to achieve this. All Western governments use the unemployed as a buffer stock (Smith, 2017).

Job Guarantee

“The general idea of a Job Guarantee (JG) is that the government offers employment to everybody ready, willing, and able to work for a living wage in the last instance as an Employer of Last Resort” (Tcherneva, 2018a). Prof. Bill Mitchell, Pavlina Tcherneva, and other heterodox economists have elaborated on that idea in order to close the inflation risk gap between not-quite-full employment and full employment (Tcherneva, 2020. Pg 116-118). This would leave frictional unemployment as the sole economic concern (Kagan, 2022). With no job guarantee, the path to full employment is susceptible to inflation after the MUIR point. However, as ecological economist Prof’ Phillip Lawn has demonstrated, it looks nothing like a Phillip’s Curve model. (See Figure 1)

JG flattening the curve when Labour is the Limiting Factor of Production.

JG flattening the curve when Labour is the Limiting Factor of Production.

Regardless of whether the Reserve Bank of Australia (or the Fed in the United States) believes an economy has passed a legitimate “NAIRU” inflation point (MUIR), very few economies, if any, actually have. Claiming that unemployment should be 4.5% when there was no rampant inflation at 2% unemployment ignores 25 years of history (Karp, 2023). Beyond real unemployment not being as low as claimed, current post-pandemic inflation was initially driven by supply-shocks and then by corporate price-gouging decisions, rather than any evident demand or low unemployment (Haly, 2022); (Haly, 2023).

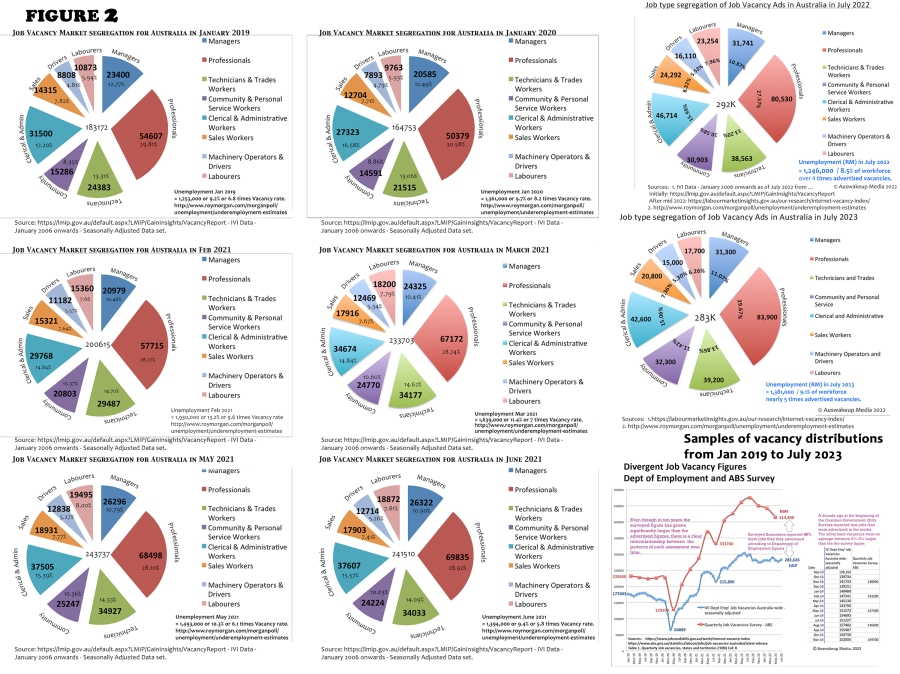

Random Monthly Job Vacancies breakdowns – 2019 to 2023

Random Monthly Job Vacancies breakdowns – 2019 to 2023

When labour is the limiting factor of production, inflation follows. Labour mismatches induce inefficiency. It affects economic productivity when an economy is near full employment, since, contrary to conventional economic beliefs, labour skills are not interchangeable. The only way they are interchangeable is if they are identical positions. Capacity, experience, and abilities matter. Accountants, labourers, or nurses cannot, for example, fill a deficit of electrical engineers. Mismatches increase when labour skill and experience deficiencies restrict productivity. People may be unable to fill employment openings, resulting in idle or unproductive labour, and therefore increasing the cost of production. This partly explains why job openings in a poorly constituted labour market (without full employment policies) go unfilled month after month, even while unemployment numbers are more significant (Haly, 2024b). (see Figure 2)

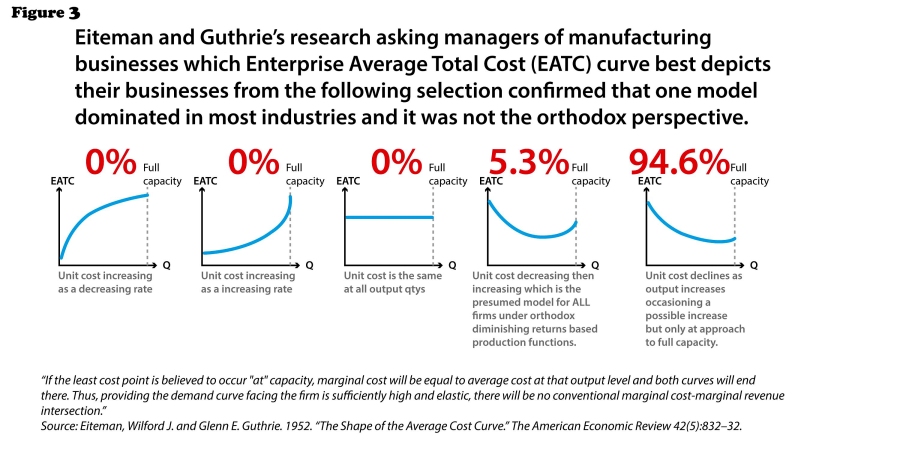

Labour costs become problematic when a mismatch occurs (not to be confused with the government’s failure to implement full employment policies). As labour becomes scarcer, efforts to produce unmatchable substitutes may cause cost-push inflation. Mismatches between labour supply and demand appear at the MUIR point (“legitimate NAIRU”). When mechanical engineers are scarce, you may employ an electrical engineer at either a higher mechanical engineering fee or as an inefficient factor of production. As full employment approaches, labour productivity declines, and expenses increase. This causes businesses costs to rise. According to business surveys, rising costs are more likely to occur near production limits. (See Figure. 3) As a firm approaches that labour limit, your average total expenses grow since each extra hour of labour is less productive. (Figure. 1) Consequently, to maintain profit margins, businesses raise prices, as they are never ones to miss an opportunity to price gouge (Prof. William Mitchell, 2024). That is from where real inflation originates as a pricing decision!

Surveyed ATC Business Curve results

Surveyed ATC Business Curve results

The MUIR

The MUIR point exists in the gap between employment mismatch and true full employment. However, while it is difficult to measure, if full-employment policies are in place, it should be less than 2% (as it was for 25 years in Australia). Figure 1 shows how it looks regarding its effects on average total costs. It should be noted that this is not the standard Phillips Curve used for counterfeit NAIRU. At this point, the federal Job Guarantee for a minimum wage should be used to consume excess idle labour without “mismatch” inflation. If not at the MUIR point, the government should hire at the award wage. You avoid cost-push inflation by consuming idle labour at the point where the event horizon of the MUIR actually exists and doing so at a minimum wage. This is where a Federal Job Guarantee, as defined above, comes into play to compensate for the inefficient excess cost of idle labour. This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the concept of an Employer-of-Last-Resort (Tcherneva, 2018b).

Current ideas of fighting NAIRU inflation through monetary rather than fiscal policy have raised recessionary concerns (Emerson, 2023). Few countries, other than Australia, have implemented full employment policies that have achieved around 2% unemployment (for 25 years with negligible inflation!) through fiscal policies. If these countries were experiencing demand-pull inflation — as opposed to cost-push inflation. It would be due to a failure to implement full employment policies in education, public employment, and mission-based economies (Kibasi, 2021). In Western democracies, full employment policies are not part of the dominant neoliberal agenda. As a result, counterfeit NAIRU employment mismatches happen much sooner than they should. Neoliberalism institutionalises governments’ inability to provide jobs for their citizens.

A change to a fully functionally productive and more egalitarian society, where everyone who wants a job may have one and worker exploitation is reduced, will require the facilitation of both full employment policies and a job guarantee. In the second section, we will examine the policy needs that are required to make this happen, together with the expectations for future labour markets that will remain unfilled in the event that these aims are not met.

Introducing the Salary Cap Act

by Daniel Wortel-London

Obscene salaries are no longer sustainable and should be illegal. (Justin Pacheco, Wikimedia)

The daily news regularly features commentary about the outrageous and growing income inequality in the USA. The data support the outrage:

- In 1965, the CEO-to-worker salary ratio at the average U.S. company was 21-to-1. Today that ratio is 344-to-1.

- In 2022, CEO pay at 100 S&P 500 companies averaged $15.3 million, while median worker pay averaged only $31, 672, according to an Institute of Policy Studies analysis.

- Since 1978, CEO pay has increased 1,460 percent.

Many reasons can be cited for opposing large discrepancies in pay, including depressed morale of employees, diminished firm productivity, and widened gender and racial disparities. Another reason is their effect on the environment. High salaries tend to increase environmental impacts. And high pay, particularly high CEO pay, is dependent on—but also drives—the economic growth that is creating today’s societal and environmental crises.

To counter inequality in the USA, CASSE proposes adoption of a Salary Cap Act (SCA). The Act would create salary caps by major occupational sector, as Brian Czech proposed in Supply Shock. Almost no expansion of the Tax Code is entailed. The SCA would simply prohibit the issuance of salaries beyond the prescribed proportions (described below), making it a crime for employers to issue exorbitant salaries.

Exorbitant Salaries and Environmental Degradation

Generating money entails agricultural and extractive activity at the trophic base of the economy. Therefore, the need to pay exorbitant salaries results in more environmental degradation than paying for lesser salaries. Imagine, for example, the ecological footprint required to pay Elon Musk compared to a minimum-wage worker.

Highly paid individuals are more likely to purchase resource-intensive luxury goods, too. This is one reason why the USA’s top one percent of income earners was responsible for 23 percent of the growth in global carbon emissions between 1990 and 2019. And income inequality leads to inequality in political power, which helps CEOs lobby for policies that promote unsustainable growth.

Limiting the environmental impact of the economy entails limits on high salaries. (Richard Hurd, Creative Commons 3.0)

High salaries drive growth in less obvious ways as well. At many corporations, CEO compensation includes a generous grant of stock and stock options. These sweeteners motivate CEOs to strive for company growth, then use profits to buy back company stock, which raises its price and enriches the CEO even further.

For example, the compensation of oil company executives is intimately linked to exploring for new fields, extracting fossil fuels, and promoting consumption of their fuels and services, activities that contribute to the growth of the firm. As Richard Heede of the Climate Accountability Institute observes, “executives have personal ownership of tens or hundreds of thousands of shares, which creates an unacknowledged personal desire to explore, extract and sell fossil fuels.”

Moreover, high CEO compensation through stock options and bonuses encourages companies to take a short-term perspective that can involve boosting stock prices quickly through shortsighted sales or risky investments. The Enron scandal, for example, involved CEOs trying to quickly raise stock prices in pursuit of bonuses. Selfish and short-sighted decisions like these can take a serious environmental toll, and are disastrous at a time when companies should be committed to the long-term health of our planet.

Drivers of Unequal Pay

CEO pay has increased extensively in part because companies have grown larger and wealthier, which allows them to offer fatter salaries. It’s also because CEOs have increased their leverage over corporate boards and can therefore set their own pay more easily. But the greatest reason is because CEOs are compensated differently than ordinary workers: Some 80 percent of CEO compensation in 2021, for example, derived from vested stock awards and exercised stock options rather than “ordinary” salaries. CEOs are thus able to negotiate salaries that are orders of magnitude higher than the salaries of workers paid through more conventional means.

Policymakers have a deep toolbox for addressing pay inequality. They can, for example, ban or tax stock buybacks or deny public contracts to companies with excessively high pay inequalities. Measures like these are now law. The Inflation Reduction Act placed a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks, while San Francisco and Portland, Oregon have taxed companies with large CEO-worker pay gaps. Inspiration comes from outside the USA as well. The European Union will assist in bailing out failed banks only when their pay ratios are 10-to-1 or less.

Franklin Roosevelt called for a 100 percent tax on annual incomes above $1.2 million (in 2022 dollars). (Elias Goldensky, Public Domain).

But another, more direct remedy for pay inequality is salary caps. We’ve seen such caps in professional sports leagues for decades, including every major league in the USA except Major League Baseball. These caps are much higher than those prescribed in the Salary Cap Act presented below, but they achieve analogous purposes. Leagues use caps to keep overall costs down and ensure a competitive balance among teams. The USA would use salary caps to for purposes of social equity, but also to keep environmental impact at a lower, more sustainable level.

Salary caps, along with caps on wealth and other forms of income, have been proposed by various economists and progressive policymakers, occasionally with public success. A referendum was held in Switzerland in 2013 to cap executive incomes; while unsuccessful, it emboldened major candidates in France and England to endorse similar salary caps. And campaigns for wealth and income caps have taken various forms in U.S. history, from Huey Long’s “Share our Wealth” campaign to Franklin Roosevelt’s call for a 100 percent tax on high incomes during World War II.

In the spirit of these efforts, CASSE proposes the Salary Cap Act.

The Salary Cap Act

The Salary Cap Act is designed to curb exorbitant salaries for purposes of social equity and environmental health. Salary caps are set and enforced by the Department of Labor. A separate provision addresses pay for self-employed workers.

The SCA defines “salaries” as wages, bonuses, tips, and other forms of compensation specified under Section 3401(a) of the Internal Revenue Code. This broad definition is meant to encompass forms of compensation, such as corporate stock options, which are not traditionally classified as “salaries.”

Section 4 describes the target and structure of the salary caps. The Secretary of Labor sets the caps for each of the 23 major occupational groupings in the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) Codes maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The caps are set, and updated annually, to correspond to 1.8 times the salary of the 90th percentile of employees for each occupational grouping. (In other words, maximum salaries in each occupational grouping are 80 percent higher than the salary at which 90 percent of salaries in the grouping are lower and ten percent are higher.)

For example, the annual salary cap for managerial occupations would be set at $400,000, while the cap for food preparation occupations would be set at $81,270. Salary disparities would remain, but they would be far lower than the disparity today. The average CEO-to-worker pay gap across occupational categories is currently 344-to-1. Under the SCA, the ratio would be roughly 7-to-1.

We can respect planetary boundaries, or we can have billionaires, but not both. (Adrian Cadiz, Wikimedia)

Meanwhile, traditional and reasonable salary discrepancies among professions are still respected. For example, licensable occupations that require extensive training or years of graduate school warrant a higher range of salaries than those for occupations requiring little training or education.

The value of 1.8 in the maximum salary formula is chosen because the salary of the President of the United States is currently 1.8 times the 90th percentile of CEO salaries. We do not believe a CEO deserves to be paid more than the president. Still, the SCA’s maximum salary formula offers plenty of room to reward superior performance while curbing the social and environmental distortions of exorbitant salaries.

Section 5 describes how the Office of Labor-Management Studies in the Department of Labor will enforce the SCA. The Office will have the power to petition a court if it believes the Act has been violated. Companies found guilty will face criminal penalties of up to $100,000,000, imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, or both.

A concluding section requires net earnings from self-employment or employee ownership in excess of $400,000 be taxed at 100 percent. Salaries derived from self-employment are not included in the NAICS SOC codes, so it is necessary to “cap” these earnings through taxation rather than salary caps.

The SCA is designed to be both a stand-alone bill and a component of the larger Steady State Economy Act. It will not, by itself, end wealth inequality or ecological overshoot. But it will help apply brakes on incentives that drive economic firms to grow the economy beyond our planet’s carrying capacity.

We also encourage the voluntary adoption of salary caps prior to passage of the SCA. In addition to contributing to the social and environmental purposes of the SCA, such voluntary caps provide a boost to employee morale and cut costs for small businesses and nonprofit organizations.

The Salary Cap Act may be revised pursuant to reader responses and the input of CASSE allies.

Daniel Wortel-London is a CASSE Policy Specialist focused on steady-state policy development.

The post Introducing the Salary Cap Act appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

“Truths” Overturned

by Gary Gardner

New perspectives reveal different truths. (Mathilda Khoo, Unsplash)

Stories that upset our worldviews can be scary, but also exciting and even stirring. They shake us out of established thinking and stoke the imagination for possibilities of a better world. Think of how effectively Hamilton made a non-white perspective on U.S. history—even regarding the founders—as valid as any other. Or how My Octopus Teacher beautifully demonstrated that wildlife are not just exotic “others” but can be touchingly relational.

In the effort to create steady state economies, stories will surely play a powerful role in upending assumptions about economy and society. A truly sustainable economy will create a new understanding of the purpose of an economy and how it works, overturning many commonly accepted assumptions. Stories can help in this transition.

I have no novel or screenplay to contribute to this storytelling effort. But to interested screenwriters I suggest a few of the “truths” such a story would likely overturn. Toppling these will shake our worldviews, but also point in the direction of a hopeful future in the steady state economy.

Economic Considerations

Let’s start with a few random economic “truths” that are destined to wither.

Cheap energy will boost sustainable economies. Societies of the future will look askance at claims, common today, that cheap, abundant energy is an unmitigated good. The current enthusiasm for mining helium-3 on the moon is a good example. Michelle Hanlon, who directs the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi, observes gleefully that helium-3, which is scarce on earth but plentiful on the moon, “could seriously power the Earth, the entire Earth, for centuries.”

Her vision may seem tantalizing, but wise policymakers and publics will pause to consider an underappreciated truth: Energy is power.

If the problem here is not evident, recall the maxim of Lord Acton: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Acton spoke of political power, but it’s easy enough to apply his insight to physical power—our capacity to do work, to move matter. Fossil fuels allowed industrial societies to move a lot of matter over the last century, to the tune of 100 million tons of materials annually in the past few years. That’s a lot of habitat lost, air and water polluted, and often, resources squandered. Our power is spoiling our prospects.

Framed this way—that fossil fuels are problematic as much for the power they hold as for the pollution they cause—it’s clear that helium-3, nuclear fusion, or any other energy source in abundance is not a cure-all unless corralled and controlled in some conscionable way. Renewables can help address our pollution and climate problems, but if humanity wields them as we did fossil power, we’ll continue to do grave damage to natural systems beyond the climate.

Economic efficiency always leads to better outcomes. Another truth to slay is the notion that we should always and everywhere seek greater efficiency in economic processes. The Jevons paradox, or “rebound effect,” warns that reductions in resource use from greater efficiency may be illusory. This is because efficiency creates paths for greater consumption. For example, individuals might reduce spending on gasoline by switching to a car with higher gas mileage, then spend the savings on a vacation in the Bahamas, increasing their overall consumption of fossil fuels.

Or efficiency might midwife new technologies that boost consumption. In a recent New York Times opinion piece, Ed Conway observed that when LED lighting was deployed in the early 1990s, analysts heralded its potential to reduce energy use. That’s because LEDs use 90 percent less energy than incandescent bulbs and last 18 times longer.

Yet energy use today is about the same as in 2010, he says, because new lighting applications (along with population growth) offset the efficiency gains. The LED is just “a chip that gives light,” observes Roger van der Heide, chief design officer at Philips Lighting, “so we can connect it to a bigger system of processors and sensors“ that make innovative uses of lighting possible. LEDs are now integrated into products from carpet to clothing to basketball courts that can be made into giant video screens. These entirely new applications for lighting boost energy use.

Philosophical Considerations

Freedom means no boundaries—The critique of unconstrained energy use described above can be expanded to the axiom that open-endedness in general is a problem, that we develop best within limits. Commercials and political campaigns argue otherwise, but surely we grasp this essential truth: Development without limits is not development at all. It’s extravagance or immoderation or sloth or some other attribute most of us don’t sign on to.

We grasp this in much of our lives. The aspiring athlete limits her free time, her food choices, and her late nights, recognizing that boundaries are key to realizing her potential. Boundaries bind, yes, but they also launch us (we bound) farther than we would otherwise go. They develop us. We understand this, except when it comes to the economy. There, boundaries are too often seen as handcuffs.

Restriction or protection? (Colin Park, Geograph)

I once heard a leader in the sustainability field remark that “Development is anything that increases your options.” The assertion rings true to a point, but it’s also unsettling. Increasing one’s options surely reaches a point of diminishing returns, and eventually having more options curdles into harm. In the USA, the plethora of food options, convenience options, gun options, and get-rich options, to name a few, are arguably unraveling the country’s development—the recent decline in life expectancy in the USA is a striking example.

A few years ago, I counted 162 different types, sizes, and brands of breakfast cereal in our neighborhood supermarket, one side of an entire aisle. I wondered if we were less developed with only 100. And should we be shooting for 200? Many cereals are simply vehicles for delivering a sugar fix to kids. Why expand this health-damaging inventory any further?

Contrast the cereals options with the life choices we describe as character-building, as developmental. Choosing a job, buying a house, committing to a spouse. These choices are not defined by an abundance of options and a world of time in which to make up our mind. In fact, isn’t the difficulty of those choices, rooted in a paucity of options, what gives these life choices their developmental character?

Nature is silent regarding boundaries: Today, businesses, consumers, and other economic actors must respect only the boundaries written in laws, norms, and other codes. In a steady state economy, a major new set of rules, congruent with natural law, will apply. How exactly those boundaries will be set is not clear, but candidate yardsticks are available and increasingly well-known. They include the planetary boundaries and ecological footprint metrics, and the trophic theory of money.

The purpose of an economy is wealth generation and material accumulation. Economists, business people, and political leaders give great attention to levels of production and consumption in an economy. But they talk much less about what gets produced. The share of wealth that goes to arms is often cited as excessive, and rightly so, but the critique could be broadened to include the myriad trinkets in our economy, those goods that serve little useful purpose or have short lifespans, yet require resources to produce. Here we can cite short-lived packaging and fads like “pet rocks.”

The natural objection is that “nobody tells me what I can and cannot spend my money on.” Fair enough; setting up an authority to regulate “acceptable” products is politically fraught. Instead, the problem will need to be addressed through education, in schools, to be sure, but also through broader tools like pricing strategies. ax materials to a point where silly products would be expensive enough to lose their markets.

The Finale

A steady state economy would likely manifest differently in various places. But some general principles might be considered by our screenwriter. Tim Jackson has long written of the need to create economies of “care, craft and culture” that enhance human well-being. Care consists of services that support wellbeing, including health care, education, and social services. Craft refers to appreciation of the material world we inhabit, manifested through an ethic of sufficiency, conservation of materials, and skills in building and repair. Culture refers to creating works of art that support communities.

This is an economy of wellbeing, for humans and nature alike. It turns on their heads many of the assumptions we carry about an economy. In an economy of wellbeing, societies will have transitioned from an emphasis on generating wealth to sharing wealth for human flourishing in collaboration with nature. It’s a story that upends our presuppositions, to be sure, but a story with a happy ending.

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

The post “Truths” Overturned appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

The Fed Is Behind The Credit Card Merger

Editor’s note: This story was originally printed on Matt Stoller’s newsletter BIG, where he explores the politics of monopoly power.

It’s an obvious point, but credit cards in America generate a lot of cash for banks. In 2022, I wrote up how the business works, with the observation that the industry generates close to a quarter trillion dollars a year in revenue. This revenue comes from fees for connecting merchants and banks, as well as fees charged to consumers for access to credit.

Every credit card network is also a data sieve, connected to advertising data brokers, anti-fraud features, and analytics firms. In addition, being able to reject someone from the payments system is a core sovereign power, and the stated reason the right is so afraid of a central bank digital currency.

There are many barriers to entry in the credit card business, and significant pricing power among incumbents. As the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) found, margins for credit cards are persistent, increasing, high, and tilted towards the larger firms in the industry. (And this is true even when you take higher interest rates into account.)

This is not a paywall. You can read the full story for free.

Just sign up below for a free subscription to The Lever to get access to this story and much more.

Already have an account? Sign in

Ending The Ivy League’s Tax Dodge

Within a one-mile radius in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sit Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — academic institutions that together boast $74 billion in endowment funds. Based on the size of these “rainy-day funds” alone, the two universities, with a combined student body of 37,000, have enough wealth to rival Ghana, with a population of 35 million.

The kicker? These private universities are educational institutions, meaning that for most of their history, they have been exempt from federal and state income taxes.

Massachusetts lawmakers want to change that. State legislators are considering a groundbreaking bill that would impose a 2.5 percent annual excise tax on private college and university endowments that are larger than $1 billion. The resulting $2.5 billion raised each year would be more than enough to cover the tuition of every undergraduate student currently attending public colleges and universities in the state.

This is not a paywall. You can read the full story for free.

Just sign up below for a free subscription to The Lever to get access to this story and much more.

Already have an account? Sign in

Appearance on The Project – Channel 10

This is a bit of a catch up post from last year when I was interviewed on The Project.

After federal Treasury’s Measuring What Matters framework came out, there was a lot of criticism about the timeliness of the data (mostly parroting a NewsCorp criticism). Amazingly, Channel 10 sent a camera crew to my house in Castlemaine (from Melbourne) to shoot this about 90 minutes before it went to air and then edited it into the smooth segment above for The Project. My interview starts after the intro at about the 2 minute mark.

What’s at stake in the inflation debate? | Mark Weisbrot

Larry Summers and others have been sounding the alarm over inflation. But are fears overblown?

Larry Summers says he’s worried about the US economy. Even more than he was worried when he started to sound the alarm in February. The well-known economist and former US treasury secretary said last week that “the focus of concern right now should be on overheating”.

He’s not talking about climate but about the economy growing too fast and running into persistent high inflation like we had in the 1970s, along with other possible crises. On the same day that he issued the above warning, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for June was 5.4% above its level one year earlier. Press reports noted that this was the biggest one-year jump since 2008.

Women in the richest areas enjoy two decades more of healthy life than their poorer sisters. Welcome to unequal England

A third of the population will not reach 60 in good health, new figures reveal. And it’s income, not lifestyle, to blame

New statistics from the ONS have revealed that women in the most deprived areas of England can expect to have 19 fewer years of healthy life than those in the most advantaged areas. For men, the figure isn’t much better, with a gap of over 18 years. To put that into perspective, those born in the poorest parts of England can now expect to live the same, or fewer, healthy years as someone born in war-torn Liberia, Ethiopia or Rwanda. And a third of people in England won’t reach 60 in good health.

The temptation, as always, is to assume that those at the bottom eat poorly, do little exercise, drink a lot and take drugs. In short, it’s their fault. But 94% of people on low incomes don’t take drugs, and people in the richest fifth are actually twice as likely to drink heavily than those in the poorest fifth. Inconvenient as this may be to some, there isn’t some inherent character flaw that only afflicts the poor.