Wellbeing

Befriending Boundaries

by Gary Gardner

Restriction or protection? (Colin Park, Geograph)

One of the most difficult adjustments industrial-country citizens will make in the steady state economy is accepting limits on our activities. Steady state economies will not be the Wild West, beyond the frontier where anything goes. We will learn to live within limits, a difficult reality for peoples accustomed to an open-ended understanding of freedom. In a “full world” where we bump up against the limits of our planet’s resources, boundaries will either be accepted willingly or imposed on us by the physical and resources limits in which we live.

If this sounds depressing, it’s likely because the resource- and energy-saturated twentieth century spoiled us into forgetting that boundaries are long part of the human experience. What’s more, boundaries and the restraint they require can help us to become our best selves. Far from succumbing to depression, we’d do well to view circumscribed activity as a boon to our development.

Restraint: Not a New Idea…

Philosophers and spiritual leaders across cultures and throughout history have taught the importance of channeling human energies within ethical boundaries. This is often expressed as a preference for avoiding extremes. The Roman playwright Terence counseled “moderation in all things.” Buddhist philosophy and Baha’i teachings stress “the middle way,” avoiding excess and scarcity equally. And Mahatma Gandhi drew on his Hindu heritage to elaborate his own “seven deadly sins,” blessings that become insidious without boundaries to guide them. They are worth listing:

- Wealth without work

- Pleasure without conscience

- Science without humanity

- Knowledge without character

- Politics without principle

- Commerce without morality

- Worship without sacrifice.

Some thinkers go further—much further. “Geologian” (geologist and theologian) Thomas Berry argued that restraint is more than merely a moral adornment on human activities, it is a fundamental ingredient of progress dating to the origins of the universe. Berry notes that gravity was essential at the Big Bang to shape a creative universe. The tremendous energy released at that formative moment needed the constraining power of gravity to shape matter into a productive cosmos. Energy alone is diffuse and produces nothing, while material alone is rigid and lifeless. But in proper balance, the two hold tremendous creative potential. For this reason, Berry argues, constraints, restraint, and boundaries are best understood as “liberating and energizing” rather than confining.

…But a Neglected One

The practical lesson of this wisdom is that we develop best within limits. Commercials and political campaigns argue otherwise, but surely we grasp this essential truth: Development without limits is not development at all. It’s extravagance or immoderation or sloth or some other attribute most of us would not want to claim as our own.

We grasp this in much of our lives. The aspiring athlete limits her free time, her food choices, and her late nights, recognizing that such boundaries are key to realizing her potential. Boundaries bind, yes, but they also launch us (we bound) further than we would otherwise go. They develop us. We understand this, except when it comes to the economy. There, boundaries are too often seen as handcuffs.

Out of Bounds? (Picryl, CCO 1.0)

I once heard a leader in the sustainability field remark that “Development is anything that increases your options.” The assertion rings true to a point, but it’s also unsettling if it means that development is open-ended or boundarly-less. Increasing one’s options exhibits diminishing returns, and having more options eventually curdles into harm. In the USA, the plethora of food options, convenience options, gun options, and get-rich options, to name a few, are arguably unraveling the country’s development. The recent decline in life expectancy is striking evidence of our backward trajectory.

A few years ago, I counted 162 different brands, sizes, and types of breakfast cereal in our neighborhood supermarket—one side of an entire aisle. I wondered if we were less developed with only 100 options. And should we be shooting for 200? The question is especially needling given that many cereals are simply vehicles for delivering sugar fixes to kids. Is it progress to expand this debilitating inventory any further?

Contrast the cereals options with the life choices we describe as character-building, as developmental. Choosing a job, buying a house, committing to a spouse. These choices are not defined by an abundance of options, nor do we have a world of time to make up our mind. In fact, isn’t the paucity of options what gives these life choices their developmental character?

Start with Energy Boundaries

The critical need for gravity to shape the energy of the Big Bang into a creative universe ought to provide a general framework for how we think about energy (and all resources) today. But our stance toward energy is anything but restrained. Too often we hear that cheap, abundant energy is the holy grail of energy development. The current enthusiasm for mining helium-3 on the moon is a good example. Michelle Hanlon, Director of the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi, observes gleefully that helium-3, which is scarce on earth but plentiful on the moon, “could seriously power the Earth, the entire Earth, for centuries.”

Clean energy, sure. Properly circumscribed? (Apollinary Kalashnikova, Unsplash)

If the problem here is not evident, recall the maxim of Lord Acton: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Acton spoke of political power, but it’s easy enough to apply his insight to physical power—our capacity to do work, to move matter. Virtually unrestrained use of fossil fuels allowed industrial societies to move a lot of matter over the last century, to the tune of 100 million tons of materials annually in the past few years. That’s a lot of habitat lost, air and water polluted, and often, resources squandered. Our power is spoiling our prospects.

Framed this way—that fossil fuels are problematic as much for the power they hold as for the pollution they cause—it’s clear that unbounded use of helium-3, nuclear fusion, or any other abundant source of energy is not a cure-all. Renewables can help address our pollution and climate problems, but if humanity wields them as we did fossil power, we’ll continue to do grave damage to natural systems beyond the climate.

Who Sets the Boundaries?

It’s reasonable to wonder who will set economic boundaries in the steady state economy. Boundary making will undoubtedly be complex and will differ by geography, historical context, and culture. But given the ecological damage driving many dimensions of the polycrisis, it makes sense to give ecological factors a high priority in boundary drawing.

Yardsticks available to help with this work include the planetary boundaries metrics, which define a “safe operating space” for humanity regarding greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and other areas of economic activity. The ecological footprint metric can also help, through its per capita measures of renewable resource use. And the trophic theory of money offers an overarching boundary for economic growth, stopping any expansion that proceeds faster than the sustainable growth of agriculture, forestry and mining, the trophic base of the economy.

Softer boundaries would be defined culturally and politically. Tim Jackson has long written of the need to create economies of “care, craft and culture” that enhance human well-being. Care consists of services that support wellbeing, including health care, education, and social services. Craft refers to appreciation of the material world we inhabit, manifested through an ethic of sufficiency, conservation of materials, and skills in building and repair. Culture refers to creating works of art that support communities.

This is an economy of wellbeing, for humans and nature alike. Its success will be rooted heavily in its capacity to set and maintain boundaries that advance the prospects of all humans for dignified lives of sufficiency and cultural richness while tending to the needs of the natural world. In such a world, boundaries will be seen not as irksome handcuffs, but as protective tools that advance the common good.

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

The post Befriending Boundaries appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

“Truths” Overturned

by Gary Gardner

New perspectives reveal different truths. (Mathilda Khoo, Unsplash)

Stories that upset our worldviews can be scary, but also exciting and even stirring. They shake us out of established thinking and stoke the imagination for possibilities of a better world. Think of how effectively Hamilton made a non-white perspective on U.S. history—even regarding the founders—as valid as any other. Or how My Octopus Teacher beautifully demonstrated that wildlife are not just exotic “others” but can be touchingly relational.

In the effort to create steady state economies, stories will surely play a powerful role in upending assumptions about economy and society. A truly sustainable economy will create a new understanding of the purpose of an economy and how it works, overturning many commonly accepted assumptions. Stories can help in this transition.

I have no novel or screenplay to contribute to this storytelling effort. But to interested screenwriters I suggest a few of the “truths” such a story would likely overturn. Toppling these will shake our worldviews, but also point in the direction of a hopeful future in the steady state economy.

Economic Considerations

Let’s start with a few random economic “truths” that are destined to wither.

Cheap energy will boost sustainable economies. Societies of the future will look askance at claims, common today, that cheap, abundant energy is an unmitigated good. The current enthusiasm for mining helium-3 on the moon is a good example. Michelle Hanlon, who directs the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi, observes gleefully that helium-3, which is scarce on earth but plentiful on the moon, “could seriously power the Earth, the entire Earth, for centuries.”

Her vision may seem tantalizing, but wise policymakers and publics will pause to consider an underappreciated truth: Energy is power.

If the problem here is not evident, recall the maxim of Lord Acton: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Acton spoke of political power, but it’s easy enough to apply his insight to physical power—our capacity to do work, to move matter. Fossil fuels allowed industrial societies to move a lot of matter over the last century, to the tune of 100 million tons of materials annually in the past few years. That’s a lot of habitat lost, air and water polluted, and often, resources squandered. Our power is spoiling our prospects.

Framed this way—that fossil fuels are problematic as much for the power they hold as for the pollution they cause—it’s clear that helium-3, nuclear fusion, or any other energy source in abundance is not a cure-all unless corralled and controlled in some conscionable way. Renewables can help address our pollution and climate problems, but if humanity wields them as we did fossil power, we’ll continue to do grave damage to natural systems beyond the climate.

Economic efficiency always leads to better outcomes. Another truth to slay is the notion that we should always and everywhere seek greater efficiency in economic processes. The Jevons paradox, or “rebound effect,” warns that reductions in resource use from greater efficiency may be illusory. This is because efficiency creates paths for greater consumption. For example, individuals might reduce spending on gasoline by switching to a car with higher gas mileage, then spend the savings on a vacation in the Bahamas, increasing their overall consumption of fossil fuels.

Or efficiency might midwife new technologies that boost consumption. In a recent New York Times opinion piece, Ed Conway observed that when LED lighting was deployed in the early 1990s, analysts heralded its potential to reduce energy use. That’s because LEDs use 90 percent less energy than incandescent bulbs and last 18 times longer.

Yet energy use today is about the same as in 2010, he says, because new lighting applications (along with population growth) offset the efficiency gains. The LED is just “a chip that gives light,” observes Roger van der Heide, chief design officer at Philips Lighting, “so we can connect it to a bigger system of processors and sensors“ that make innovative uses of lighting possible. LEDs are now integrated into products from carpet to clothing to basketball courts that can be made into giant video screens. These entirely new applications for lighting boost energy use.

Philosophical Considerations

Freedom means no boundaries—The critique of unconstrained energy use described above can be expanded to the axiom that open-endedness in general is a problem, that we develop best within limits. Commercials and political campaigns argue otherwise, but surely we grasp this essential truth: Development without limits is not development at all. It’s extravagance or immoderation or sloth or some other attribute most of us don’t sign on to.

We grasp this in much of our lives. The aspiring athlete limits her free time, her food choices, and her late nights, recognizing that boundaries are key to realizing her potential. Boundaries bind, yes, but they also launch us (we bound) farther than we would otherwise go. They develop us. We understand this, except when it comes to the economy. There, boundaries are too often seen as handcuffs.

Restriction or protection? (Colin Park, Geograph)

I once heard a leader in the sustainability field remark that “Development is anything that increases your options.” The assertion rings true to a point, but it’s also unsettling. Increasing one’s options surely reaches a point of diminishing returns, and eventually having more options curdles into harm. In the USA, the plethora of food options, convenience options, gun options, and get-rich options, to name a few, are arguably unraveling the country’s development—the recent decline in life expectancy in the USA is a striking example.

A few years ago, I counted 162 different types, sizes, and brands of breakfast cereal in our neighborhood supermarket, one side of an entire aisle. I wondered if we were less developed with only 100. And should we be shooting for 200? Many cereals are simply vehicles for delivering a sugar fix to kids. Why expand this health-damaging inventory any further?

Contrast the cereals options with the life choices we describe as character-building, as developmental. Choosing a job, buying a house, committing to a spouse. These choices are not defined by an abundance of options and a world of time in which to make up our mind. In fact, isn’t the difficulty of those choices, rooted in a paucity of options, what gives these life choices their developmental character?

Nature is silent regarding boundaries: Today, businesses, consumers, and other economic actors must respect only the boundaries written in laws, norms, and other codes. In a steady state economy, a major new set of rules, congruent with natural law, will apply. How exactly those boundaries will be set is not clear, but candidate yardsticks are available and increasingly well-known. They include the planetary boundaries and ecological footprint metrics, and the trophic theory of money.

The purpose of an economy is wealth generation and material accumulation. Economists, business people, and political leaders give great attention to levels of production and consumption in an economy. But they talk much less about what gets produced. The share of wealth that goes to arms is often cited as excessive, and rightly so, but the critique could be broadened to include the myriad trinkets in our economy, those goods that serve little useful purpose or have short lifespans, yet require resources to produce. Here we can cite short-lived packaging and fads like “pet rocks.”

The natural objection is that “nobody tells me what I can and cannot spend my money on.” Fair enough; setting up an authority to regulate “acceptable” products is politically fraught. Instead, the problem will need to be addressed through education, in schools, to be sure, but also through broader tools like pricing strategies. ax materials to a point where silly products would be expensive enough to lose their markets.

The Finale

A steady state economy would likely manifest differently in various places. But some general principles might be considered by our screenwriter. Tim Jackson has long written of the need to create economies of “care, craft and culture” that enhance human well-being. Care consists of services that support wellbeing, including health care, education, and social services. Craft refers to appreciation of the material world we inhabit, manifested through an ethic of sufficiency, conservation of materials, and skills in building and repair. Culture refers to creating works of art that support communities.

This is an economy of wellbeing, for humans and nature alike. It turns on their heads many of the assumptions we carry about an economy. In an economy of wellbeing, societies will have transitioned from an emphasis on generating wealth to sharing wealth for human flourishing in collaboration with nature. It’s a story that upends our presuppositions, to be sure, but a story with a happy ending.

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

The post “Truths” Overturned appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Envisioning a Steady-State Comprehensive Plan

by Dave Rollo

”Economic growth” is commonplace in the daily news. We assume it’s a good thing, that a 2–4 percent increase in GDP is beneficial to all. Likewise, we hear that our communities are growing, and we see a 2–4 percent increase in population as reasonable and benign. Meanwhile, visionary community leaders are busy planning for a steady feed of single-digit annual growth. So we’re in good hands, right?

Too often, new homes claim farmland. (Brett VA, Flickr)

But what the news reports miss is that any steady rate of growth is an exponential function that contains within it a knowable doubling time. Suppose a reporter added this: “County officials say that at 3.4 percent growth annually, our county will double in population in just over 20 years.” Would this capture our attention? Would we respond differently? A doubling of population, of water demand, of schools needed, of traffic! And what about taxes?

Suppose the reporter further spelled out the meaning of this growth. “Developers are proposing new housing tracts on the farmland just outside town. If trends continue, the radius of our city will double in two decades.” The intrepid reporter continues: “Doubling the radius of Central City will quadruple the built area of our community!” Now the mind is reeling. Time to pull the car over. What are these county leaders thinking?

The reporter might also note that the expansion of our built environment is doing measurable harm to our environment and quality of life. Two examples: The USA is losing farmland at a rate of 1.8 million acres per year. And more than 40 percent of groundwater wells in the U.S. are declining faster than they are recharged. It seems growth is not so benign after all.

Local communities need more than ever to safeguard their own life-support systems by taming growth and retrofitting existing dwellings and neighborhoods to respect limits. This requires reality-based community planning, typically reflected in a fundamental document: the comprehensive plan. A comprehensive plan has long been the means to regulate development in an orderly fashion. Now it must evolve to help towns and cities live within limits set by nature.

The Evolution of Community Planning

Most counties and cities within the USA have a long-range plan that anticipates urban expansion. The Comprehensive Plan (sometimes referred to as a “Growth Policy Plan”) was developed early in the twentieth century as the need for universal community planning became clear. At that time growth was expected and invariably desired. Growth promised more of everything, including tax revenue for local government. Comprehensive plans promised an ordered development by zoning for specific uses and building public infrastructure to serve them.

Visions are exciting, but boundaries matter, too. (Parisa, Flickr)

Cheap energy helped create cheap transportation, which encouraged physical expansion and accelerated the conversion of farmlands and wildlife habitats into housing tracts and strip malls. This post-World War II conversion was lamented not only by conservationists, but by urbanists of the day, who foresaw the drawbacks of sprawl such as pollution, traffic congestion, and social isolation. The manifest problems of sprawl began to be recognized widely in the late twentieth century. In response, “smart growth” was promoted to ameliorate the worst effects of unimpeded expansion.

At about the same time, comprehensive plans began to incorporate broader themes, including community vision and values, retention of community character, the value of ecological services, and quality of life. This expanded view, while reflected in only a minority of comprehensive plans, laid the groundwork for challenging the growth mandate. It advances the public good not just via quantitative metrics of physical material or GDP, but also through the use of measures of human wellbeing. It enables questions such as, “What is the optimal size of our community?”

A Path to Real Sustainability

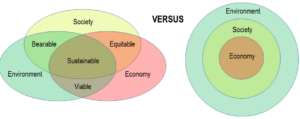

Municipalities and counties that envision quality of life beyond simple growth metrics have often incorporated the concept of sustainability into their planning documents. Supposedly sustainability is achieved at the intersection of the environmental, social equity, and economic dimensions of community life.

Partial and more accurate visions of sustainability, respectively. (Penn State)

While helpful in some contexts, this intersectional approach to planning allows “sustainability” to be acknowledged while denying any need for limits on economic expansion. This denial is never made directly but in a workaround fashion. For example, the American Planning Association professes a concern about climate change but endorses “smart growth” adaptations to address the climate threat, despite the obvious and long-documented relationship of greenhouse gas emissions to GDP.

A fundamental requisite of a steady-state comprehensive plan is to acknowledge that human economies are subsidiary to the biosphere. Therefore, local plans should incorporate limits that preserve biocapacity for humans and our fellow species. This is explicitly described in the ordered hierarchy of sustainability, in which the economy is embedded in society, which in turn is nested in the environment. It should appear in the introduction to the comprehensive plan. An example would be the Bloomington, Indiana Comprehensive Plan Executive Summary: “Our community has resolved to do our share to protect the biosphere, and critical to this protection is recognizing that infinite growth is neither possible nor desirable in a finite world.”

The most basic obligation of local government is the health, safety, and welfare of the community. Meeting this obligation requires a stable climate, productive and regenerative food systems, and biodiversity conservation. Protecting these natural assets necessitates limits to growth of the built environment.

Integrating real sustainability in a community’s comprehensive plan requires taking into account the carrying capacity of land under community control. It also requires impact measures such as ecological footprint analysis that describe impacts relative to the biocapacity of the area. Carrying capacity and impact analysis represent important inputs to the design of a zoning code to limit growth.

A Framework for a Plan

Modern comprehensive plans begin with a vision statement for the community followed by a summary of the plan and the relevant chapters for its implementation. A vision for a county intending to create a steady state economy would acknowledge limits to the GDP growth of the county and to its physical expansion. This vision could be affirmed in a statement—perhaps a “Declaration of Limits”—by the elected representatives of the county or municipality and adopted by the county commissioners or the city council.

Plan Ithaca. (Ithaca, New York: Vision for Our Future).

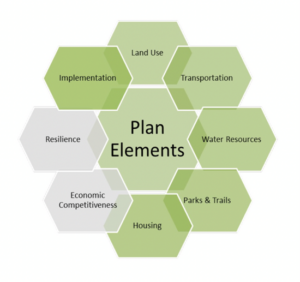

A steady-state comprehensive plan would then focus on preserving the county’s natural capital, green infrastructure, and agricultural land while improving and building upon the community’s historic, cultural, and civic assets. These goals can be detailed in the plan’s chapters, directing departments within the local government to implement programs and policies to achieve the objectives of the plan. The plan can also provide a benchmark for progress.

The structure of a steady-state comprehensive plan would be similar to that of a conventional growth-oriented plan. Functional areas such as transportation, economy, housing, and land use would offer guidance to planners and elected bodies in dealing with important infrastructure works and sectoral activities. But instead of a growth-oriented approach to development, steady-state plans would emphasize qualitative optimization of each topic.

For example, transportation planners might halt road expansion and focus instead on expanding public transportation and building trails for biking and walking. They might also create, through land-use planning, residential/work nodes that minimize the need for travel. These efficiencies would be aligned with sustainability goals that aim to reduce energy and carbon emissions.

Steady Statesmanship, Chapter by Chapter

The Economy chapter would focus on wellbeing and would adopt quality-of-life objectives in place of measures of GDP. (To be clear, GDP could be used as a measure of environmental impact—not quality of life—in which case county leaders would seek to contain it, rather than expand it.) For example, the chapter would expand economic development to include the work of social service agencies. The county’s Economic and Sustainable Development Department would prioritize supporting local business as a means of cultivating real, sustainable prosperity. And a prime focus would be to recirculate wealth by substituting locally-sourced goods for imports.

Comprehensive plan elements. (Twin Cities Metropolitan Council)

The Housing chapter would prescribe compactness of form—of housing developments as well as of houses. Goods and services would be provided within walking distance or a short public transit ride. Amenities and services such as garden space, orchards, laundries, and tool shops would be nearby and compact. Building codes would be adjusted to favor using local materials, and to aim at low-impact energy use.

The Land Use chapter would have special importance in the Comprehensive Plan. Based on measures such as ecological services, agricultural use, species richness, watershed protection and other metrics of biocapacity, areas outside those reserved for human habitation would be placed in Conservation Districts. Likewise, Rural Preservation Areas would aim to preserve farmland by allowing only low-density human habitation. To further limit expansion, the Plan would include an urban services boundary and create a greenbelt of rural land that precludes urban development.

The Details are in the Data

Comprehensive plans are the chief guiding documents of a city or county. But clear data and analyses are also needed to guide policy decisions. Preservation of biocapacity is an important goal, but policymakers will need to know the locations of natural areas and farmland, and their characteristics such as biodiversity or agricultural productivity, in order to formulate the proper policies.

Likewise, elected representatives could best advocate for limits if the costs of growth are fully accounted for. Growth impact assessments that include cost calculations are indispensable. These assessments should include direct costs of infrastructure and services as well as indirect costs including the loss of ecological services and the reduction in biocapacity.

Community footprint analyses that quantify human economic and social demand on the county’s natural capital provide a clear basis for protecting the reserve capital through land preservation and reducing human impact through other policies, such as efficiency measures in building and transportation. Where footprint analysis is not available, county GDP should be used as an indicator of environmental impact.

Natural capital should be integral to urban planning. (Randy von Liski, Flickr)

Other reports and action plans that complement a steady-state comprehensive plan are already being utilized by many communities. Climate action and sustainability plans provide strategies to lessen energy consumption. Local food charters offer ways of expanding the local food economy to protect farmland, provide employment, and provide for county food security. Reports on import replacement and establishing a diverse local economy offer ways to build community wealth by recirculating dollars as an alternative to the wealth building that is presumed to come from continual expansion.

The process of creating a Steady-State Comprehensive Plan will require engaging citizens. Surveys indicate that many citizens see growth and sprawl as a pressing problem, with one poll reporting that 77 percent of Americans see sprawl-driven destruction of farmland and natural habitat as a major problem or somewhat of a problem. Given this sentiment, community leaders should be asking a crucial question: What is the ideal size of our community?

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

The post Envisioning a Steady-State Comprehensive Plan appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Appearance on The Project – Channel 10

This is a bit of a catch up post from last year when I was interviewed on The Project.

After federal Treasury’s Measuring What Matters framework came out, there was a lot of criticism about the timeliness of the data (mostly parroting a NewsCorp criticism). Amazingly, Channel 10 sent a camera crew to my house in Castlemaine (from Melbourne) to shoot this about 90 minutes before it went to air and then edited it into the smooth segment above for The Project. My interview starts after the intro at about the 2 minute mark.