economic justice

We have a tax time bomb waiting to explode in the UK. Is Labour going to let it go off?

I have spent much of this afternoon, a) talking to journalists and b) trying to work out how the Budget adds up.

The first task was relatively easy. The second was less so.

In part, the great cost saving in the Budget is on interest: it has been assumed that the cost of government borrowing will fall quite quickly to 3% rather than the 4% assumed last November. That finds £10 billion.

But, that was not enough, so I went on a hunt for the rest that explained how Hunt was going to give tax away. I finally got to Table A5 of the Annex to the Office for Budget Responsibility's Economic and Fiscal Outlook publication that supports the Budget data, and there I smelt a rat.

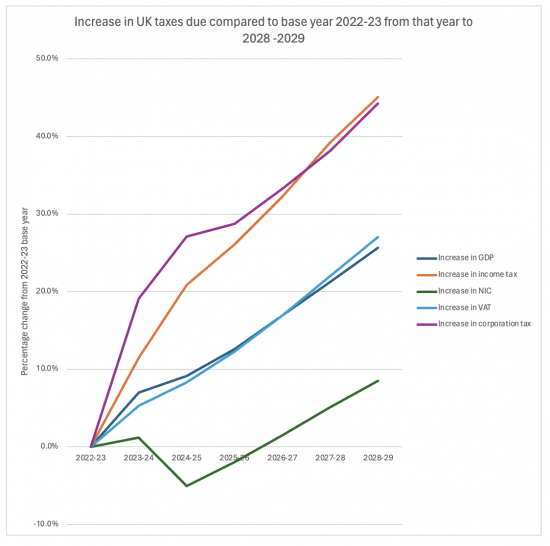

I prepared the following chart by noting n0minal GDP from table A3 of that annex for 2022-23 to 2028-29 and then noting data from table A5 on income tax, national insurance, VAT and corporation tax over the same years.

Then I calculated GDP and tax receipts for each year as a ratio of the 2022-23 figure to show growth in them, and then plotted this to get this chart:

The two blue lines in the centre that almost match each other are GAP growth and VAT, which unsurprisingly match each other almost exactly.

National insurance declines markedly: Hunt is pretending that he really will get rid of this tax.

But then note what happens with both income tax and corporation tax: both rise at rates well over anything that can be justified by the growth in GDP.

Corporation tax is a small tax; silly forecasts can be made for it, and this one is absurd: profitability is not going to grow at that rate.

But, income tax is what really matters. The forecast increase is utterly disproportionate. The growth in tax owing each year is at a rate almost double the rate in the growth of GDP.

To put this in context, income tax shown to be due in 2028/29 is £48 billion more than it would be if it grew at the rate of GDP growth.

In other words, the actual rates of income tax increase we will all actually be suffering because of fiscal drag over the next few years are going to be very high indeed - and that is how Hunt is supposedly balancing its books.

In that case, the real question to ask is, what is Labour going to do about this? We have a tax time bomb waiting to explode in the UK. Are they going to let it go off?

The Taxing Wealth Report 2024: a pre-Budget summary

The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 and the Budget

In anticipation of the UK budget this week, I thought it important to provide a summary of the work that I have been doing on the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

That report will be published in full shortly. All the recommendations noted below are listed on a single page of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, from which links to detailed workings are supplied.

Introduction

The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 was written for one primary reason. Its aim was to demonstrate that the claim made by politicians from both the UK’s leading political parties that there is no money left to support the supply of better public services in the UK is not true.

The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 shows that there is the potential to raise around £90 billion of additional tax revenue each year from fairly straightforward reforms to the UK’s existing tax system.

All of these reforms would result in additional tax being paid only by those who are better off. Unless a person’s income comes mainly from investments or rents, very little of what the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 suggests would have very much impact on them unless their income exceeded £75,000 per year. This would, however, be fair. As the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 shows, those with wealth in the UK are massively undertaxed compared to those who work for a living. Correcting this imbalance is entirely appropriate, simply in the interest of social justice.

Importantly, whilst the detailed workings underpinning the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 have required a lot of research, the ideas implicit in the recommendations made are quite straightforward. So, for example, it is suggested that pension tax relief should only be provided at the basic rate of income tax whatever the highest tax rate of the person making the contribution. If that change was made an additional £14.5 billion of tax would be paid in the UK each year.

It is also proposed that national insurance should be paid by anyone on their earnings from work at the same rate, and that the reduction in that rate that now applies for those earning more than about £50,000 a year should be abolished. This might raise more than £12 billion in tax a year, assuming national insurance rates used in 2023.

If an income tax charge equivalent to national insurance was also made on all those with income from investments and rents or capital gains exceeding in combination £5,000 a year, then that simple change might raise £18 billion in revenue each year whilst removing an obvious injustice within the tax system that has also been widely exploited by those seeking to avoid tax.

Aligning income tax and capital gains tax rates when there is no obvious reason why they should differ might raise a further £12 billion of tax year.

If only HM Revenue & Customs could be persuaded (or funded) to collect tax from all small companies that owe it when at least 30% of that revenue is lost each year at present due to under-investment in its collection, then maybe £6 billion a year of extra corporation tax might be collected, plus as much again in additional VAT and PAYE which is also likely to be lost from those companies not paying the corporation tax that they owe.

Charging VAT on the supply of financial services, almost all of which are consumed by those with wealth, might raise £8.7 billion a year, having allowed for existing insurance premium tax payments.

Numerous other, smaller, tax changes could also be made, whilst some inappropriate charges, like those for student loans that only raises £4 billion a year for what is, in effect a tax, could be abolished.

On top of all this, what the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 also shows is that if the conditions attached to tax-incentivised savings in ISA and pension fund accounts were changed, then up to £100 billion of savings per annum could be transferred from their current speculative use to become the capital that is necessary to underpin the transformation of the UK economy. That money could either be invested in our crumbling state infrastructure, or in the transition that is necessary to beat the impact of climate change. Incentives for such tax-incentivised savings accounts now cost £70 billion a year, which is more than the UK defence budget. Almost no social benefit currently arises from this massive subsidy to wealth. In a country where there are £8,100 billion of financial assets, this transformation will not rock financial markets, but it will transform the future prospects of the UK.

That transformation might come in three ways.

Firstly, and vitally, inequality in the UK might be addressed. The tax owing by those on low pay has to be reduced and the benefits that they enjoy have to be increased if everyone is to have a chance of fully participating in the UK economy without the stress that millions now suffer.

Secondly, if the UK government undertook measures to tackle inequality and simultaneously spent more on recruiting suitably qualified people to supply UK government services of the standard that is now needed to meet our current health, social care, housing, justice and environmental crises, then the boost to household incomes that would inevitably follow would provide the basis for the growth that every government claims to be necessary. Growth cannot come before that spending takes place. It would, as a matter of fact, follow it.

Thirdly, the UK has under invested in its own future for decades, having placed all its savings into the care of the City of London, who have used them for speculative activity rather than for the creation of real economic activity. Correcting that by redirecting tax incentivised savings into investment in the essential underpinning of the economy that we need might, yet again, generate new income for the UK’s private sector and households, whilst ensuring that we are equipped for the very different future that we must face.

Having money available will not guarantee that the UK will have a better future. However, without there being money available, that future is not possible. The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 demonstrates that more than enough money is available to transform our society, to increase the incomes of those in need in the UK, to create growth, to stimulate employment, to increase the well-being of our companies, and to underpin the investment that we require. No politician can now say otherwise. The fact is that the choices that they can make are explained in this report. If they do not wish to use the options that it demonstrates are available, it is for them to explain why. However, what none of them can ever claim again is that there is no money left, because it is there for them to ask for whenever they wish to use it, and that is precisely why the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 matters.

Summary of proposals

The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 is made up of a series of proposals for the reform of taxes and the administration of tax in the UK, with some selected supporting explanatory notes also being added.

These proposals and the value of the reform that they suggest are as follows:

All of these proposals are summarised in a single page of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 with links being provided there to the detailed workings that support the suggested benefits arising.

Reforming the organisation, goals and funding of HM Revenue & Customs

I have this morning published the last substantial chapter of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024. Some introductory and concluding sections have still to be completed, but this note focuses on the need to reform the organisation, goals, and funding of HMRC and is the last that makes substantial recommendations that will be included in the report.

When I started work on the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, I thought that this section would be one of the first to be completed, largely because I have looked at issues relating to the underfunding of HMRC since 2010. However, as my research on the subject developed it became clear that to discuss funding in isolation made no sense because to do so would have ignored the context within which this matter is of concern.

As the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee has noted in the latest of their many reports on the failings of HMRC, published this week, there is a long-term and marked downward trend in the quality of service supplied by HMRC to taxpayers. They also imply that many of the claims that HMRC's management is making concerning its own performance have to be open to doubt.

Within this context, looking at the claimed improvements in efficiency that HMRC suggest have resulted from the substantial reduction in its workforce cannot be justified. HMRC‘s costs are now rising, significantly. This issue is addressed in detail in this chapter.

Worse, a detailed review of the tax gap, the reduction which is used by HMRC to justify its supposed ever-increasing control of tax collection, cannot support that claim. HMRC admit that around 30% of corporation tax owing by smaller companies goes unpaid each year. They also accept that 18% of tax due by unincorporated small businesses goes unpaid, which they suggest to be a significant improvement on 2015, when more than 30% of those taxes went unpaid. However, data on on-time tax return submissions and data published by HMRC in 2022 showing that they had discovered that more than 8% of the UK population might be involved in the shadow economy, almost all of whom are self-employed, sharply contradicts this claim of an improvement performance in this area. As such this tax gap is highly likely to be at least as large as that for small limited liability companies.

This evidence then suggests that those most in need of help from HMRC to comply with their tax obligations are not getting that help. As a result of HMRC economies, tax offices have been closed, face-to-face taxpayer support has ended, telephone helpline support has become incredibly difficult to access, and online help has proved to be no substitute. Txaayers have been left bewildered by their obligations and alienated from HMRC, and it is not surprising that tax gaps are out of control.

That this is the case might also be due to the fact that HMRC is managed as if it is a large public company and not as a public service. The fact that all its non-executive directors represent the interests of the wealthy and large companies only reinforces the inappropriateness of its focus.

The consequences of all this are that a substantially more radical approach to the reform of HMRC is required than is currently proposed by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. It is time to re-organise HMRC so that its focus is on providing taxpayers with the support that they need to meet their tax obligations. At present, far too many of those taxpayers are alienated by IT systems and the demands that they create that taxpayers, quite reasonably, cannot comprehend.

It is, as a result, time for HMRC to restore its local office presence so that people can be provided with face-to-face advice on their taxes.

In addition, HMRC also needs to restart its programme of support to small businesses that are struggling to meet their obligations by reinstating its programme of active engagement with small traders by reviewing their books and records on-site to make sure that they are tax compliant.

What all this also implies is that HMRC‘s headlong rush towards Making Tax Digital is not just inappropriate but is the totally wrong way in which the UK should manage its tax system.

A tax system should be a public good, meaning it is a service supplied without the intention of profit arising by an agency that is seeking to maximise public well-being. The UK tax system does not meet that criteria at present, largely because of failure on the part of HMRC's senior management.

We need a radical overhaul of the management of the UK tax system if it is to be fair, transparent, accountable, open, accessible, and dedicated to creating equality within the UK because everyone is required to pay the taxes that they owe.

The summary of this chapter, which is of 33 pages in total, is noted below. A PDF version of the whole chapter is available here.

A copy of this chapter will be sent to the Public Accounts Committee.

Brief Summary

This note suggests that:

- HM Revenue & Customs governance structures are no longer fit for purpose. They are based on the ethos of a public company and are focused almost entirely on meeting the needs of large companies and the wealthy. Both sectors are well represented amongst its non-executive directors; no other group in society is. That is no longer acceptable.

- HM Revenue & Customs has for too long emphasised cost control as its focus of concern rather than serving taxpayers or raising all the revenue owed to it. This has been inappropriate and has prevented the creation of a tax system suited to the needs of society in the UK.

- HM Revenue & Customs’ drive to reduce the cost of collection of tax in the UK has largely failed but has as a consequence:

- Seriously reduced the quality of service that it supplies to taxpayers in the UK, with the quality of everything, from face-to-face services to the answering of telephone calls, to the time taken to reply to letters, all deteriorating significantly leaving many taxpayers without any of the help that they need to pay the right amount of tax that they owe.

- Seriously reduced the number of staff at HM Revenue & Customs.

- Reduced the average real pay of staff at HM Revenue & Customs.

- Considerably reduced the number of tax investigations undertaken each year.

- Lost control of some major parts of the tax gap, which is the difference between the tax that should be paid and the tax that is actually paid in a year.

- Tax gap measurement has been used by HM Revenue & Customs’ management as the indicator of its success, but as has been explored in other parts of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, the claims made with regard to the tax gap in general are open to question.

- One of the two tax gaps where it is very apparent that matters have got out of control is that for small companies, where around 30 per cent of corporation taxes owing now go unpaid each year, which is way in excess of any reasonable level of loss. The likely annual cost of this loss is now £5.9 billion per annum.

- Another tax gap that is likely to be out of control is that for the 5 million small businesses that pay their taxes via the income tax system. HMRC say this tax gap has fallen from around 32.5 per cent of these taxes owing going unpaid in 2014 to only 18.5 per cent being unpaid now. They have not, however, provided any convincing reason for this improvement in taxpayer compliance, which is not matched by improvements in equivalent rates for small companies or in the overall rate of timely tax return submission, half of which returns come from self-employed business owners. The claimed current rate of loss is unlikely to be realistic in that case and an excess loss of maybe £3.4 billion is likely to arise as a result in this area, largely because HMRC has withdrawn from local tax offices that previously supported these taxpayers and from active monitoring of their onsite activities through their now largely abandoned programme of business compliance visits.

- In combination, the losses from just these two tax gaps amount to maybe £9.3 billion and can be attributed to HM Revenue & Customs mismanagement of its activities in the community, whether that be through maintaining local offices where face-to-face help is available or by visiting businesses at their own premises.

- It also seems that HM Revenue & Customs’ claims for the benefits of its Making Tax Digital programme seem to be seriously overstated, which is a fact repeatedly noted by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. The costs of creating this programme appear to be out of control. The costs it imposes on business taxpayers are excessive. Worst of all, it is likely to alienate millions of people from the tax system and most likely increase the tax gap as a result, rather than reduce it. It also makes the UK a significantly worse place in which to run a business, which is likely to impose serious costs on society at large.

- As a result, this report recommends that:

- That HMRC reforms its governance structures and objectives.

- HMRC restore its local office help centre presence in towns and cities across the UK, and widely advertise the availability of this support service.

- HMRC’s should restore its programme of site visits of businesses to monitor their tax compliance to cover checking both PAYE and VAT records.

- HMRC should stop the rollout of its Making Tax Digital programme so that no business that is not VAT registered will never be enrolled in this programme.

- The cost of restoring these services will be very much less than the sums that might be raised by reducing the two gaps that have been noted to reasonable levels (i.e. those that were maintained during periods when HMRC was better resourced in the past), but since some of those sums capable of recovery have already been noted elsewhere in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 no additional account of such recovery is made here. That said, because other tax gaps would also undoubtedly improve if HM Revenue & Customs were to re-establish its presence in UK towns and cities the likely cost of this programme – which might be £1 billion a year, or twenty per cent of the current cost of running HMRC - is not taken into account either. Nor is the likely significant gain from reducing taxpayer strain taken into consideration, or the gain from making the UK a more tax-friendly environment, to which considerable harm has been done since 2010.

Unless we put the UK’s wealth to work for social purposes we really are in very deep trouble

I have noted a report in the Guardian this morning which suggests that Southwark Council is seeking to raise £6 million of crowd-sourced funding over the next six years, which it will use to fund climate change-related investments in its borough. It is offering to pay 4.6% interest on the sums it is borrowing at present, which is a lower rate than it would have to pay HM Treasury to borrow the same money. It is, apparently, one of nine councils undertaking such arrangements at present and secured £50,000 of funding within hours of its new scheme being open.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that I find much to applaud in this arrangement, albeit that I despair at the current approach adopted by HM Treasury, which is penalising councils for seeking to borrow to achieve such vital objectives. Twenty-one years ago, Colin Hines and I wrote our first ever report, working with Alan Simpson, who was a Labour MP at the time. It was called People’s Pensions and was published by the New Economics Foundation. It suggested that pension savings should be turned into the capital required by local authorities and other public administrations to fund the investment required in their communities. Local authority bonds were to be the instrument of choice for this radical transformation.

I have never given this theme up. We live in a country where there is reported to be £8,100 billion of financial wealth and a simultaneous desperate shortage of investment. That is because almost none of that financial wealth represents sums actually available for constructive use within the economy. It is instead either money sitting out of circulation in bank accounts or sums saved for speculative purposes, much of it represented by the ownership of shares in quoted companies or the ownership of second-hand buildings.

The old economic idea that saving had anything to do with investment, which claim provides the logic for the UK government still giving £70 billion of tax relief to those saving money into economically dormant or socially useless ISA or pension accounts, has been shattered in a wholly financialised economy where doing something as unseemly as actually using saved funds to provide capital for real economic activity never appears to occur to anyone in so-called financial markets.

I applaud Southwark for trying to re-establish this relationship between a saver and the constructive use of capital within a local economy. It is entirely appropriate.

What I find disheartening is that those saving in this way will not enjoy a government guarantee on the funds that they make available to Southwark when that guarantee would be provided if they put the money, uselessly, into a bank deposit account.

What I also find unacceptable is the fact that this proactive funding will not enjoy the tax subsidy that either ISAs or pension investments do.

That is precisely why I have suggested that in future, all existing types of ISA accounts should be withdrawn and the only option available for those wishing to save an ISAs should be that the funds in question be used to invest in the green economy, either by buying bonds to be issued by a Green National Investment Bank, the return on which would carry an implicit government guarantee, or by investment in shares and bonds issued by banks, public or private companies, all of which would be required to prove that the money that they had entrusted to them was used to provide capital for investment in new economic activity intended to assist the UK’s transition to becoming a net – zero economy.

I have also, repeatedly, over 21 years, suggested that part of all new pension contributions should be used for the same purpose as a condition of the tax relief provided on such sums to those making pension contributions.

Currently, £70 billion a year goes into ISA accounts and sums well in excess of 100 billion go into pension arrangements. The combined cost of tax relief on these sums is £70 billion a year, a figure in excess of the UK defence budget. In exchange, there is no obvious return of any sort to society, but enormous benefit does arise to the city of London and to those who are already wealthy, who are the inevitable beneficiaries of this largesse from the state, which they zealously seek to preserve whilst criticising all those who claim any form of benefit.

Until we join up the obvious dots in the economy and require that savings be reacquainted with investment and that tax relief only be associated with the achievement of a social purpose, we are not going to tackle the immediate issues that plague us, whether they be a shortage of gainful employment, massive under-employment, a lack of investment, or our failure to tackle the climate crisis. Rebuilding the relationship between saving and investment in a way that tackles all these issues is an obvious way to go forward, but to date no political party has shown willingness to adopt this approach, which I find deeply discouraging. However, Southwark and other councils do appear to be showing the way. I welcome that. The rest of the country needs to follow the path that they are blazing the way because unless we put the UK’s wealth to work for social purposes we really are in very deep trouble.

The government’s deliberate policy of prejudicing the poorest in our society is imposing destitution on millions

A number of related themes are apparent in commentary on the economy this morning.

One is poverty. As the Guardian notes:

Millions of people – including one in five families with children – have gone hungry or skipped meals in recent weeks because they could not regularly afford to buy groceries, according to new food insecurity data.

According to the Food Foundation tracker, 15% of UK households – equivalent to approximately 8 million adults and 3 million children – experienced food insecurity in January, as high food prices continued to hit the pockets of low-income families.

This is a tale of destiution and misery in the UK.

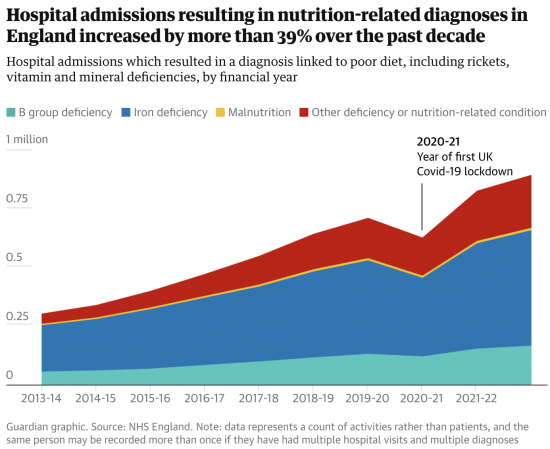

They add this graph:

We have a health crisis not just caused by Covid (although that is still very real) but by the existence of poverty thanks to George Osborne and successive subsequent Tory Chancellors, soon the be perpetuated by Rachel Reeves. That crisis is not just personal; it is collective in its cost.

Then there is this in the FT:

A lack of available loans from traditional UK lenders is pushing vulnerable consumers towards unregulated credit products as they struggle financially in the cost of living crisis, according to a study.

The UK nonprime lending market — which offers loans to riskier customers with average to low credit scores — has shrunk by more than a third since 2019.

In contrast, unsecured loans from unregulated lenders, such as those offering buy now, pay later (BNPL) products, have jumped in recent years, according to research from credit-checking platform ClearScore and consultancy EY.

The result is that the most vulnerable people in the UK who need to borrow to meet unexpected costs because they have little, or usually no, savings are being forced into the highest cost, most abusive, arrangements. It was this concern that motivated a post I made yesterday: you would never have known it from the comments of the right-wing trolls who poured in during the day to offer abuse, and who got deleted for their efforts.

And finally, there is this, also in the FT but reported in a remarkably similar style in the Guardian:

Jeremy Hunt’s financial planning is “dubious” and “lacks credibility” and the chancellor should not announce tax cuts in next week’s budget if he cannot lay out how he will fund them, an economic thinktank has said.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) calculates that Hunt would need to find £35bn of cuts from already threadbare public services if he plans to use a Whitehall spending freeze to pay for pre-election giveaways.

A fresh round of austerity in unprotected departments would boost the chancellor’s war chest for tax cuts, the independent tax and spending watchdog said, but an increase from an expected £15bn of headroom to about £50bn over the next five years would come at a high cost.

That cost will, in very large part, be seen in the perpetuation of poverty. The lowest paid will suffer tax rises. They will have the services that they need cut. The NHS, social care and housing will not be properly funded. Education, that was the route out of this, is unable to meet need. And benefit increases have not met inflation-hiked prices for basic commodities. And Hunt wants to make all of this worse.

A government unable to admit that there is Islamophobia in its rank hopes that rows on that issue will distract attention from another pressing concern, which is that its deliberate policy of prejudicing the poorest in our society is imposing destitution on millions and relative poverty on us all because of the opportunities lost to the communities in which we all live.

The upward redistribution of wealth

Investment advisers Hargreaves Lansdown issued a press release this morning saying:

Debts cost an average of £406 a month – as arrears mount

-

The average household spends £406 on monthly debt repayments, excluding the mortgage. Those with mortgages spend an average of £814 on top of this.

-

Almost one in ten households (9%) are in arrears. Among the lowest fifth of earners this rises to 27%.

-

One in five people are concerned about their debt position.

-

Credit card debt is up 12.7% in a year to £68.9 billion and other consumer debt (including loans, overdrafts and car finance) is up 6.7% to £150.4 billion (Bank of England).

The arrears data worries me, as does the increase in credit. But so too does the bigger picture.

There are about 27 million households in the UK. Around £132 billion is being paid by those households a year to service debt interest, exclusion mortgage costs. That is a staggering upward annual redistribution of wealth. And you wonder why I want interest rates to be as low as possible? That’s the reason why. Those without wealth are being exploited by those with it, and that is a recipe for an unstable society, which is exactly where we are heading.

We desperately need a Green New Deal and our power elites would rather ignore that fact

As the Guardian's morning comment newsletter says in its introduction this morning:

Houses in the UK are some of the oldest and least energy efficient in Europe. A new report by Friends of the Earth and the Institute of Health Equity found that 9.6m households are living in cold, poorly insulated homes. These households also have incomes below the minimum for a decent standard of living, meaning that they cannot afford to install double glazing or insulation, for example, to make their homes warmer. The analysis comes just weeks after the Labour party U-turned on a key climate proposal, which included a pledge to insulate millions of homes. Meanwhile, over the last 13 years the government has reversed plenty of policies designed to tackle the insulation problem in the UK.

It's now more than fifteen years since I co-authored the first Green New Deal report. In that report, we called for the release of a 'carbon army' of well-trained people who could insulate Britain, install solar power and build the transmission networks for a new economy. There would be long-term employment on offer as a result. The UK would go green. And energy poverty would be tackled. It was an all-round win.

It has not happened.

Labour has now turned its back on the idea.

But we need this solution more than ever.

And it could be done. The Taxing Wealth Report 2024 shows that the funding is available. All that is lacking is the will.

Rather than tackle gross tax, income and wealth inequality in the UK, both our leading political parties would rather balance the government's books, subject us to the desires of the City of London and maintain the existing hierarchies of financial power within our society, which leave millions in poverty whilst denying us a future.

Why do they do that? Because they crave to be part of the financial power elite, and that elite knows that and bribes them with its inducements as a result.

I would expect this of Tories.

But we have to conclude that Labour has now been totally corrupted.

That is what is frightening about where we are. Morals, ethics, principles and values have left Labour. All that is left is a vacuum desperately seeking power.

Why isn’t Labour interested in company fraud?

There was an article in the FT yesterday suggesting that the price of incorporating a company in the UK may be too low and that the reforms that the UK is introducing next month may be wholly inadequate to tackle the risks that the UK’s almost non-existent company law administration regime has created.

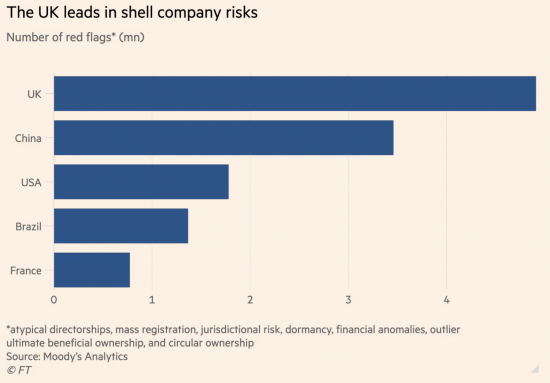

As they noted, the UK creates the largest number of red flag money laundering risks with regard to company incorporations in the world:

This is unsurprising. Because companies can be formed for next to nothing in the UK and the annual fee for retaining a company is just £13 a year, the resources made available to Companies House have been far too small for it to have had any chance of administering the more than 5 million companies that exist in this country, which figure is way an excess of any reasonable needs as indicated by comparison with other equivalent countries in Europe, as well as in the USA.

What the FT did not mention was the extraordinary cost that this failure also creates within the UK. I estimate in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 that maybe £12 billion of tax is lost each year as a consequence of the UK’s failure to regulate companies in any meaningful way.

£6 billion of this cost arises because of HM Revenue & Customs' totally lax attitude towards corporation tax compliance.

The other £6 billion is the result of Companies House facilitating tax losses of all sorts, including of VAT and PAYE, that should be due by companies trading in the UK from which Companies House does not demand accounts and instead strikes them off its register, in the process aiding and abetting their fraud that then goes entirely unpunished.

The Labour Party has always, supposedly, been interested in creating a level playing field. If it was it would take up this issue because taking crooks out of the economy is the best possible mechanism available to any government seeking to support vibrant markets. I have not, however, ever heard anything from Labour on this issue. I presume, as a result, that it is not interested in level playing fields, vibrant economies, or taking crooks out of the economy, let alone in finding £12 billion of missing public revenue. Why not completely baffles me.

Tax and money flows within the economy

This post is the third of the three that relate to the economic ideas underpinning the Taxing Wealth Report 2024. The first was on tax and money in the political economy. The second was on the national debt.

This note is a little more applied and demonstrates diagrammatically how money appears to move around the economy after a government has created it to fund its expenditure and the resulting tax and savings flows that rise as a result. It also demonstrates how those flows are impacted by QE, but more importantly, by the recommendations made in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

I’ve been asked for a diagrammatic representation of this sort for some time, but I have always held back because, to be candid, preparing these diagrams was not a straightforward exercise, and some of them went through a number of iterations. I also thought that four diagrams would suffice until, on review, the second and third diagrams were requested, and I realised that adding them made complete sense.

This post is long, with a total of almost 7,000 words in all. A PDF version is available here and might be easier to read for many people.

There are many conclusions that can be drawn from the diagrams in this paper, but a number appear particularly important.

One is that the government could borrow a lot more effectively and at a lower cost if it encouraged the people of the UK to save with it directly.

Another makes clear that the government's dependency on financial markets is not just fictional but is a fiction that the government itself has created.

Some figures are also very noticeable. One is that the estimated total cost of tax abuse since 2010 is, according to HM Revenue & Customs, £435 billion, although it could be much higher than that due to deficiencies in their methodologies.

The other is the total £800 billion cost of pension tax relief given since 2010.

These two numbers, together, explain more than 85% of UK government borrowing since 2010. Despite that, almost no attention is given to them in debates on tax, debt and economic issues. Highlighting such deficiencies in the quality of debate is one of the purposes of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

I hope that this paper is of use. Comments made in good faith will be welcome.

Brief Summary

This note is part of the background materials that seek to explain the basis for the recommendations made in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

In this paper the money flows created by government expenditure, and the resulting demand by a government for funds, are explained through a series of six diagrams.

The intention is to show how the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 seeks to:

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects resulting from government spending of new funds into the economy.

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects arising from the best choice of tax rates, meaning that those on low incomes should have low overall effective tax rates and that those on high incomes should have higher overall tax rates, which delivers this outcome.

- Provide reason why the government should encourage more direct saving in the savings products that it makes available for this purpose that together are often described as the national debt but which might be much better thought of as national savings.

- Explain the cost of tax abuse to the government in terms of excess borrowing that it has to take on as a result, which has amounted to not less than £435 billon since 2010.

- Demonstrate the cost to the government of pension saving subsidies that might have cost £800 billion since 2010, or fifty-five per cent of the so-called national debt incurred in that period.

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects from saving so that new investment can be generated from this activity which has not been the case for many decades in the UK, with a resultant boost to our economy, employment, and growth as well as to the creation of the capital infrastructure needed to address climate change and other social issues in the UK.

In the process the paper also hopes to expand understanding of the nature of the cash flows resulting from government expenditure and to slay some of the myths commonly told about that issue.

This paper suggests that the proposals in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 will have larger positive multiplier effects than the existing tax system does.

Background

As the section of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 on economics, money, tax and their intimate relationship demonstrates, much of what is true with regard to these matters is counter-intuitive to what is still commonplace understanding, particularly amongst politicians, economic commentators, journalists more generally, and tax specialists.

As that section makes clear:

- Government expenditure must precede the raising of taxation revenues or there would be no money available to pay taxation liabilities.

- The money spent by the government into the economy is newly created for it by the Bank of England every time that expenditure takes place. Most importantly, tax funds received are never involved in that process, meaning that they can never be a constraint on spending.

- The money created as a result of government spending financed by the Bank of England is withdrawn from circulation in the economy to prevent inflation taking place by way of taxes being charged and by what is commonly called government borrowing, but which would be much more accurately described as government deposit-taking from savers seeking a safe place for their funds.

- Government created money is called base money. It is not, however, the only money in circulation within the economy. Commercial banks can also create money, which they do by making loans to customers. Importantly, just as the government does not use tax revenues to fund its expenditure, nor do commercial banks use funds deposited with them to make loans to their customers. Instead, every loan that they make creates new money which is in turn cancelled when that loan is repaid, just as government created money is cancelled when taxes are paid.

To fully understand the role of tax in the economy, and the way in which the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 seeks to exploit that understanding to improve the well-being of people within the UK by both changing who pays tax and the way in which tax incentivised savings arrangements work within the UK economy, the money flows that government spending and tax (which really are the flip side of each other) create within that economy need to be understood. A series of diagrammatic representations of those money flows will be used for these purposes.

The following should be noted with regard to these diagrams:

- These diagrams might be entirely incomprehensible to some readers, and if that is the case, simply skip this chapter. Most of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 can be understood without them, but it is hoped that these diagrams will assist understanding for some people.

- Diagrams, like maps, are representations of reality but are not real in themselves. They, inevitably, simplify matters to avoid excessive complication. It is important to appreciate that this has been done in the diagrams that follow.

- Crucially, the diagrams that follow are only intended to represent the flows arising from government expenditure and the government’s consequent demands for taxation revenue and savings flows to the government. Flows primarily or solely associated with commercial bank money are not shown in the diagrams. It is accepted that this could be a basis for criticism of them, but there are two reasons for accepting this compromise:

- Firstly, the diagrams would almost certainly be incomprehensible if they also reflected commercial money flows.

- Commercial money flows are, in reality, impossible to differentiate from those created as a consequence of the use of base money within our economy, at least when we come to make payments through our own bank accounts. To abstract base money flows in the way done in these diagrams is not, then, a hindrance, but actually serves to highlight something that is otherwise not apparent.

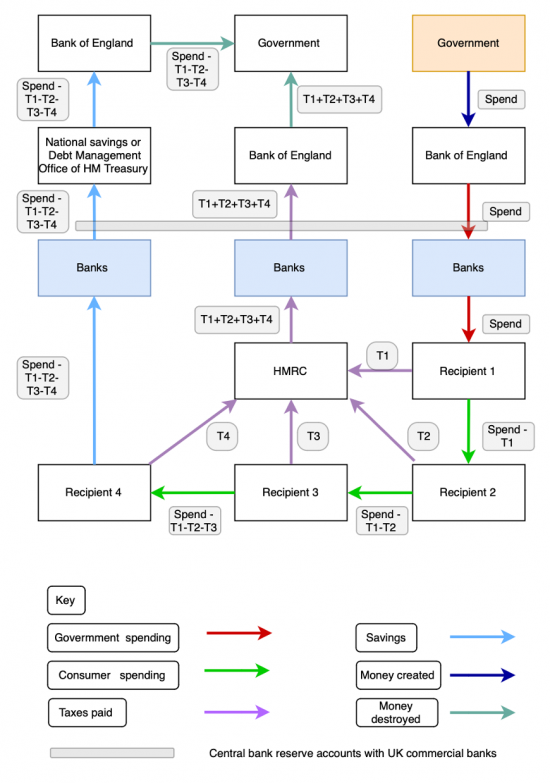

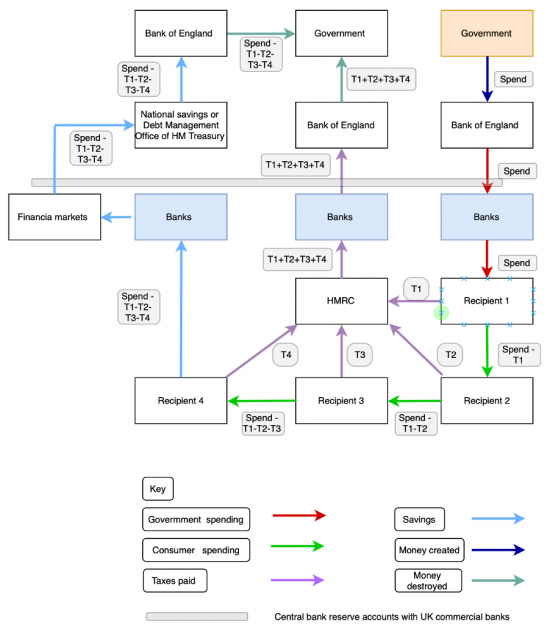

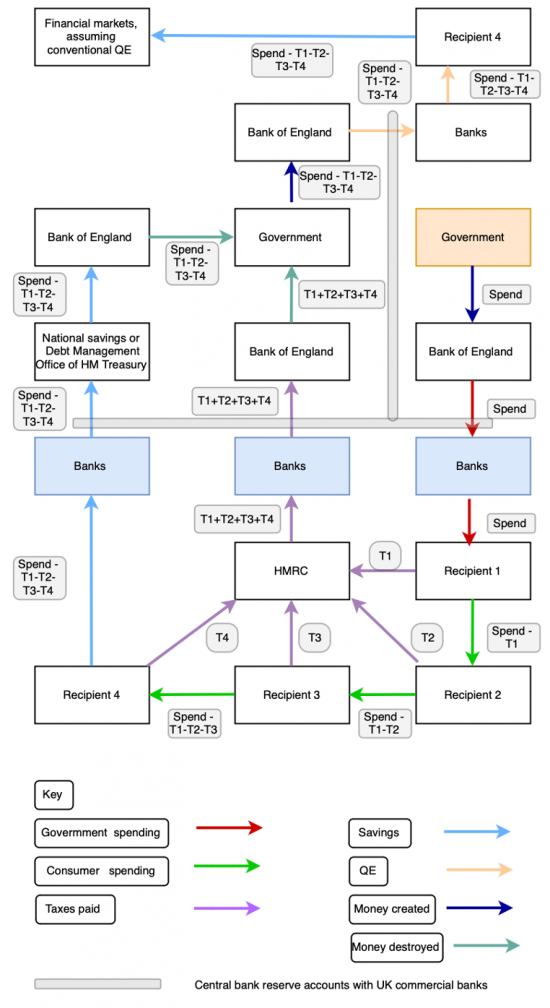

First diagram – the essential tax, spending and savings flows resulting from government spending

The first of the diagrams that explains these money flows sets the pattern for all the diagrams that follow, in which it is always embedded as they grow in complexity:

The process which the diagram portrays starts in the top right corner, with the government (indicated in this case by a box highlighted in pale orange) deciding to spend, as a consequence of which it instructs the Bank of England to make a payment. The Bank of England creates the money for the government to do so.

The Bank of England then routes this payment via the central bank reserve accounts[3] (indicated throughout the following diagrams by the grey line crossing the flows shown) to a commercial bank, highlighted in blue.

That commercial bank does, then, in accordance with the instruction that it has received from the Bank of England make payment to the first recipient of the funds from the government, effectively creating commercial money with the backing of the base money payment from the Bank of England in the process[4].

The identity of the first recipient of funds from the government does not particularly matter. It could be a commercial organisation receiving payment in respect of services supplied to the government, or it might be a teacher, civil servant, or NHS employee in respect of wages due, or it could be the beneficiary of a state pension or other state benefit. The important point to note is that they decide to undertake two transactions upon receipt of the funds.

One is to pay the tax due on the funds received, which it is assumed represents income in their hands, with that payment going to HMRC, and being described as T1 on the diagram.

The second payment that they make is to Recipient 2, from whom the first recipient buys goods or services to the value of the payment made to them, net of tax owing, to them by the government.

Recipients 2 and 3 then repeat the transactions undertaken by Recipient 1, except that the value that they will receive is reduced in each case by the amount of tax paid by previous recipients, so that, for example, Recipient 3 pays tax on the sum that they have received which is equivalent to the gross value received by Recipient 1 less the tax paid by Recipients 1 (T1) and 2 (T2). Recipient 3 then also pays tax (T3).

Recipient 4 breaks the pattern of spending following the receipt of funds. They make settlement of their tax liability (T4) but then saves the whole net balance of funds that they have received and does so by placing this net sum on deposit with a government agency. That agency might be National Savings and Investments (NS&I), or it could be the Debt Management Office of HM Treasury as a result of them buying government gilts. For the purposes of this exercise, it does not matter which. The essential point is that the funds that they have saved flow back through their bank and onward through the central bank reserve accounts to the consolidated fund of the Bank of England, and in turn, therefore, to the government’s accounts. Money is cancelled as a result.

As will also be noticed, HM Revenue & Customs also collect the various tax payments made to it in a commercial bank (it usually uses Barclays for this purpose) which in turn then remits those funds through the central bank reserve accounts back to the Bank of England, and so once more to the government, where the money in question is cancelled.

The representation is, of course, simplified. It is very unlikely that each recipient will spend all the money that they have received with a single further recipient. Recipients 2, 3 and 4 can in this case be seen as typifying all the potential beneficiaries of the funds received by Recipient 1. Each of these might still, however, have taxation liabilities that will be settled.

It also need not be the case that no saving takes place until funds reach Recipient 4. There could be saving by each previous recipient, but this would only complicate the diagram.

Finally, it is, of course, the case that some funds might be saved with commercial banks or other entities, but this would then require that commercial bank created money be reflected in the diagram because it would then be commercial bank created money that would be redirected into savings with the government if, as the government always now does, it seeks to meet any deficits between its spending and taxation receipts by issuing bonds, Treasury Bills, or by attracting savings to NS&I.

These points having been made, the simplified diagram does represent the substance of the flows that are created by a single payment by the government to a recipient, for whatever reason it might arise.

The following points might then be made:

- As will be apparent, the tax generated by the government as a consequence of the payment that it makes is not restricted to the tax payment owing by the initial recipient. It is, instead, dependent upon the number of recipients of the net proceeds of the payment that there are until such time as those net proceeds are saved, and therefore taken out of circulation within the economy. Maximising the number of times that the net proceeds are spent increases the tax yield. The aim of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 is, therefore, to keep those funds in use for as long as possible to increase the net tax recovery from the payment made in ways noted below.

- Increasing the tax rates on those who are most likely to save the net proceeds of the initial payment when they receive it, both at the time of that receipt and when they receive the income that they derive from doing so, provides some compensation for the failure of those persons to maintain the multiplier effect that might otherwise exist, and in the process provides compensatory tax yield because of their failure to pass those proceeds on within the active economy. This explains the desire in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 to increase tax rates on savings.

- Reflecting these contrasting tax positions is one of the key underpinning economic logics of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024. By redistributing tax payments due from those on low pay to those on high pay the value of net proceeds circulated in the economy by those with high marginal propensities to spend (the lower paid, in other words) increases the likelihood that overall taxes payable as a result of government expenditure into the economy will eventually rise, whilst increasing taxes on those with high pay on both that income and their savings income is a recurring theme of the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 because doing so compensates for the low multiplier effect resulting from more of their income being saved.

This chart might be relatively simple but it allows these essential points to be made.

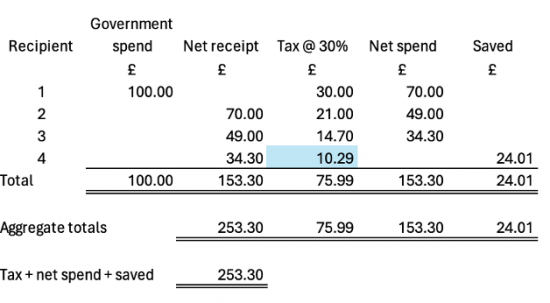

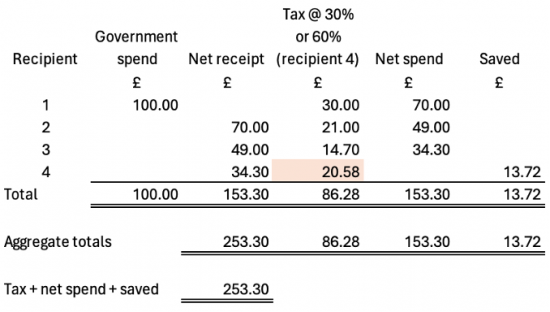

What the chart also makes clear is how a single payment can have impact much greater than is initially apparent. For example, assuming that each of the recipients noted on the diagram pays tax at an overall rate of 30% and the payments flow as indicated, and then assuming that the initial payment was of £100, the resulting flow of funds would be as follows:

The total income recorded within the economy as a consequence of the initial expenditure of £100 by the government would be £253.30. Total tax paid will be £75.99 and the balance of the initial spend would be represented by £24.01 that would flowback into government sponsored savings products of one sort or another.

If it was then assumed that recipient 4 had a tax rate of 60% because they enjoyed a higher overall level of income that permitted them to save the entire proceeds of their labour, then the above noted table would change in the following way:

The tax paid by Recipient 4 would in this situation have doubled from £10.29 to £20.58, with a consequent reduction in their level of saving. Total tax paid would now have increased to £86.28 with the net balance of the initial £100 expenditure by government now being compensated for by reduced savings of £13.72. The scale of government borrowing is reduced as a consequence of the use of appropriate rate tax rates that reflect the relative incomes of the participants in this process.

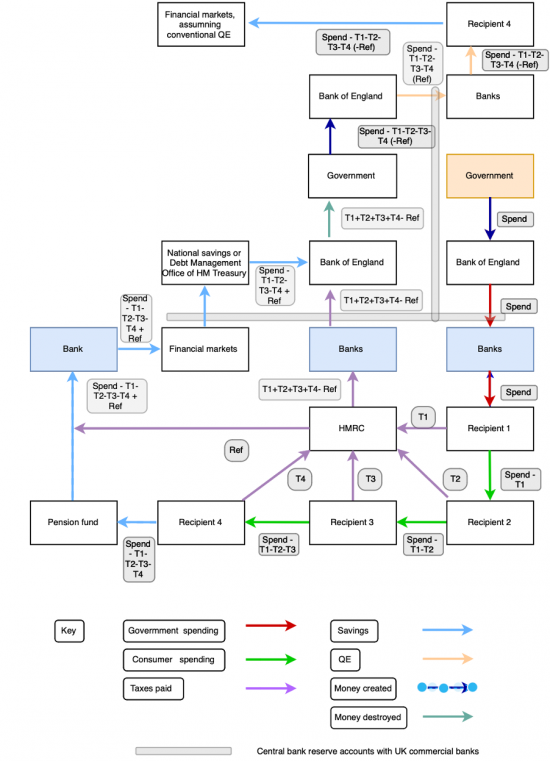

Second diagram

The second diagram in this series is a simple variant on the first. The only change is in the use of Recipient 4’s savings. Instead of these now going from Recipient 4’s bank straight to National Savings and Investments or into a gilt holding which Recipient 4 then holds in their own name those funds are instead diverted into financial markets, where they are saved.

This then creates a situation where the government is short of cash flow, as it will not borrow on its Ways and Means Account with the Bank of England. As a consequence, an apparent dependency on financial markets on the part of the Debt Management Office of HM Treasury seems to be created as it appears from the flows credited by Recipient 4 that the Debt Management Office now needs to borrow from financial markets. It does not of course: it is only convention that demands that this borrowing take place. The diagram does, however, show that this borrowing does occur.

This diagram shows that:

- This borrowing from financial markets would not be necessary if the government, via the Debt Management Office, was willing to borrow direct from the public. As it is less than 0.2 per cent of UK government bonds are owned by the public, which makes almost no sense at all[5].

- The cost of government borrowing could be reduced if more use was made of direct borrowing from the public. NS&I pays less than Bank of England base rate on the accounts it provides, and less than the cost of gilt offerings in most cases. It could raise rates and still pay less than the cost of gilt offerings whilst being competitive in savings markets. To encourage the use of these accounts would, therefore, make complete sense.

- If the public held more gilts in their own names they would make a greater return than doing so via financial intermediaries who charge for arranging such holdings. It would be easy for the government to make this facility available, but it chooses not to do so.

- The myth of dependency in financial markets has, then, been created by governments: it is not true that it actually exists. Borrowing from financial markets is not necessary at all, and if borrowing is required there are other ways to secure funds.

The obvious conclusion is that the government is not minimising the cost of its borrowing by structuring its borrowing as it does. As importantly, it is not borrowing in a way intended to suit the needs of those who wish to save securely within its own population. In the process it has created an economic myth about its dependency on financial markets. It is hard to avoid the feeling that this is deliberate.

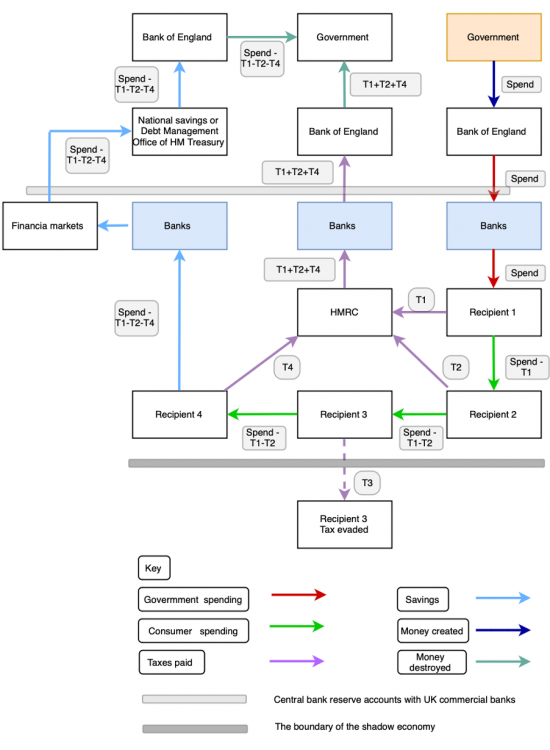

Third diagram

The third diagram is a variant on the second, for convenience.

The change shown in this diagram is that the third recipient of funds, Recipient 3, does not pay their tax and instead diverts their income and the tax that should have been paid on it into the shadow economy, as it made clear at the bottom of the diagram:

This does not mean that the money T3 receives cannot be spent: much of it might well flow through a bank account in the seemingly legitimate economy e.g. T3 might be a company that appears to be appropriately trading but never declares that fact to HM Revenue & Customs. They simply increase their own effective purchasing power by not paying the taxes that they owe. After all, why else would someone tax evade?

Their doing so means that Recipient 4 might receive more than they might have done as a result of T3 not paying their tax. It could be argued that the tax liability that Recipient 3 should have paid is simply passed on to be paid by Recipient 4 as a result, but that is not the case. If Recipient 3 received £49 (as noted in the example in the discussion on Diagram One) and should have paid £14.70 of tax on that, but did not, then Recipient 4 might receive £49 and pay tax of £14.70 but the tax that they would otherwise have paid of £10.29 on the net receipt that they should have enjoyed if T3 had settled their tax liability is lost, permanently.

The consequence of Recipient 3’s tax evasion is that total tax paid is reduced and the sum saved by Recipient 4 is increased by the same amount, quite legitimately on their part.

Overall, however, the tax evasion leaves the government more exposed to borrowing if it wishes to balance its budgets.

Since 2010 HM Revenue & Customs suggest that the UK tax gap has totalled approximately £435 billion, assuming that the two most recent years for which estimates are not yet published continue to have tax gaps at the rate of the last published year[6]. The Office for Budget Responsibility has suggested that national debt over that same period has increased by about £1,450 billion[7]. In other words, almost exactly thirty per cent of all UK government borrowing over the period from 2010 to 2024 arose because of the failure to close the UK tax gap. Because of the weaknesses in the UK’s tax gap estimates[8] the actual tax gap would be at least twice the amount that HM Revenue & Customs estimate. The evidence that large parts of the UK’s national debt have arisen because of the failure to collect tax owing due to the underfunding of HM Revenue & Customs is very strong.

Fourth diagram

The fourth diagram in this series is based on the first diagram with the flows being expanded as follows:

As should be apparent, except for four additional boxes at the top of the diagram, everything is much the same as in Diagram One. However, in this diagram it is assumed that quantitative easing (QE) is taking place. As a result, the government-backed products savings purchased by Recipient 4 in the previous diagram are now repurchased from them with new money created for that purpose. The Bank of England is effectively funded to do so by the Treasury, which has to give explicit consent for this action to take place[9]. The Bank of England then makes a payment to the commercial bank that Recipient 4 uses to settle this liability (as a result expanding the value of its central bank reserve account, with the grey line representing the boundary between base and commercial money that the central bank reserve accounts represent being extended to represent this transaction). Recipient 4, now being denied the opportunity to save with the government, which has effectively reduced the value of its product offering as a result of QE, has to instead save in the private sector financial markets, whose liquidity and value increases as a result, as was always the stated intention of QE.

The flows clearly suggest that QE:

- Reduces the value of government debt because that part previously owned by Recipient 4 is no longer available for sale, and is now owned by, and is effectively cancelled, by the government.

- QE has increased the liquidity of the financial sector, effectively by creating new reserves, which is what inflated central bank reserve accounts represent.

The sums saved in financial markets are treated as being outside the active economy shown at the bottom of the diagram because that is what the savings process does: it removes money from use in the active economy. As a result quantitative easing was largely used to fund speculation and not to fund useful economic activity in the UK economy, to its overall cost.

Fifth diagram

The fourth diagram can now be developed again in this fifth diagram of flows:

What has been added to the diagram here are pension contributions. It is assumed that Recipient 4 now decides that instead of saving in government-based savings accounts (gilts, or NS&I products) that they will instead be motivated by the tax incentive that the government provides to them to save the net proceeds of the receipt that they enjoy into a tax approved pension arrangement.

The whole of the net proceeds that Recipient 4 enjoys are now shown as going to a pension fund rather than to a national savings product. However, because of the tax incentives provided for pension saving, HM Revenue & Customs now provides a refund of tax paid by Recipient 4 to the pension fund which flows with the contribution that Recipient 4 has made through a bank account and into financial markets, where it is saved.

What is now apparent is that there are a number of costs to the government from this pension savings arrangement. One is, very clearly, that the cost of the tax refund made on the pension contribution reduces the tax flows from HM Revenue and Customs to the government via the Bank of England.

Another consequence is that savings previously held with the government are now held in financial markets. For convenience, it is assumed that these saved funds are then returned from financial markets to the Debt Management Office to be invested in gilts, so balancing the government’s cash account, but what is clear is that these tax incentives are likely to reduce direct saving with the government in the way that they are offered at present.

QE arrangements are still, however, shown as taking place. That is because these are not necessarily dependent upon repurchasing bonds issued to savers in the current period, but can be used to purchase bonds put into circulation in earlier periods.

The fundamental point made is, however, that this tax incentive provided to pensions is a subsidy to financial markets that can potentially impact the government’s own financial position by reducing revenue and by reducing sums saved directly with it. The government is then forced to borrow the cost of the subsidy it has provided to financial markets back from those markets if it wishes to balance its cash flows, paying for the privilege of doing so. If the government thinks itself financially constrained this demonstrates the very real social cost of the £70 billion cost of this pension subsidy.

The cost of subsidies that have been provided to those savings in pension funds since 2010 have amounted to approximately £800 billion. The increase in the so-called national debt over that same period has been approximately £1,450 billion. Approximately fifty-five per cent of all government borrowing since 2010 has been necessitated by the cost of pension subsidies provided to those using such facilities, most of whom were already wealthy enough to save.

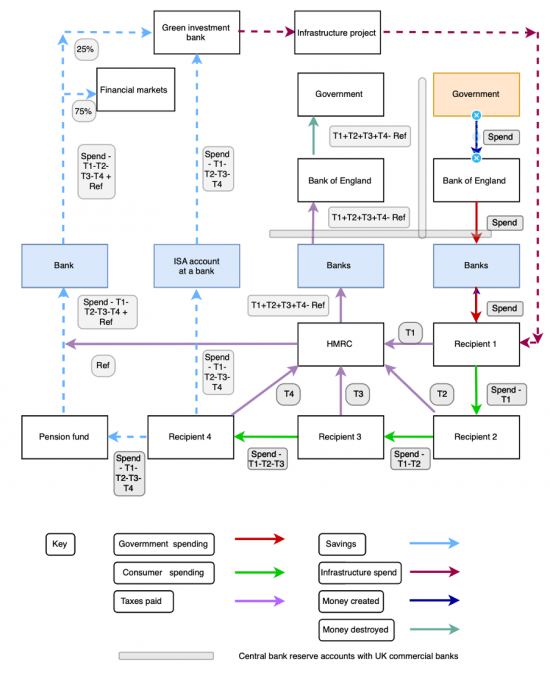

Sixth diagram

A final iteration of this diagram can be offered to explain some of the changes to the tax incentives for savings made in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

In this final diagram in this series, a number of new assumptions are made.

The first is that conventional quantitative easing has been cancelled, removing those parts of the diagram that referred to this.

Secondly, it is assumed that Recipient 4 now saves in one of two ways (or splits their saving in two ways: this need not be specific for the purposes of the diagram and explanation of it). Part is saved in a pension fund where, as is suggested in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, twenty-five per cent is invested in a way that creates new infrastructure investment in the UK economy. For these purposes, it is assumed that these funds do not go to financial markets but do instead go to a green investment bank. Financial markets receive the remaining seventy-five per cent of the funds saved by Recipient 4, including their tax refund.

Thirdly, another part of Recipient 4’s savings are placed in an ISA account at a bank, with those funds then being used by a green investment bank for the purposes of infrastructure investment in the UK economy, as again suggested as a requirement for ISA saving in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

As is apparent from the diagram, the changes to the required investment of funds saved if tax relief is to be enjoyed have a significant impact on the economy. Conventional saving, whether in cash or in traded financial products, has the effect of withdrawing funds from active use in the economy.

This is by definition the case when saving takes place in cash deposits, because they are never used to fund loans.

That is almost invariably the case with funds saved in financial markets because those markets very rarely provide new capital to businesses for investment purposes, but do instead trade assets already in existence, such as quoted shares already in circulation or buildings that have already been constructed. Funds saved in this way are, therefore, shown in this diagram as being removed from circulation in the active economy.

In contrast, funds saved in tax incentivised savings arrangements in the ways proposed in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 are instead routed into new infrastructure projects, as the diagram makes clear.

In practice, although sums saved in ISA accounts do not enjoy the same tax benefits as pensions, meaning the total sum saved in an ISA by Recipient 4 is smaller than it would be in a pension because no immediate tax relief is received, because only part of pension savings are directed towards green and infrastructure investment and all of ISA savings are directed for use in that way in the recommendations made by the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, the actual benefit to the economy from ISA savings might be greater than from pension savings if the recommendations in this report were followed.

The consequence of saved funds being used as capital for infrastructure investment is that additional spending has to take place into the economy to secure the service of those who will work on these projects. The precise sum involved cannot be known given the options available in the diagrammatic representation shown, and therefore dashed lines are used for these purposes. However, what is clear is that these funds when saved in this way return from the savings economy into the active economy as shown by the line on the right-hand side of the chart.

Recipient 1, which could just as easily be a company as an individual in this diagrammatic representation, sees their income rise as a result of the spending on new capital projects. As a result, the whole process of fiscal multipliers described when discussing Diagram One, above, begins all over again as a consequence of this new input into the economy, which has indirectly arisen as a consequence of the change to the rules on tax reliefs associated with savings products. As such, instead of those tax relief now being used as an effective subsidy to both wealth and the financial services industry, they are now instead being used to promote economic activity in the country that then generates wealth and income. Fiscal multiplier effects result that amplify that gain. These multiplier effects are not, however, shown separately in this diagram because it would become too complicated.

Conclusion

Subject to the obvious limitations required when simplifying a complex system into diagrammatic form, these diagrams do demonstrate a number of the key economic ideas that underpin the proposals made in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024, all of which have been designed with the intention of creating more and more socially beneficial economic activity within the economy.

For example, in Diagram One the particularly important point is the existence of multiplier effects. The normal representation, commonly made by politicians, is that government expenditure is the equivalent of money being poured into a black hole. Multiplier effects make clear that this not the case. That is because government expenditure is, as must always be the case within any macroeconomy, someone else’s income. That income is then taxable, almost invariably creating an immediate return to government, which fact is also almost never referred to when discussion on the way in which government is to fund its spending takes place.

As that diagram also makes clear, in addition to expenditure by a government creating new income for its first recipient, on which taxes are paid, that recipient can then create additional income for other people as they, in turn, spend the net proceeds that they have received after making settlement of the tax that they owe. This process then continues until saving takes place, which process of saving stops the multiplier effect working any further, assuming that the funds saved are then deposited in savings mechanisms that do not give rise to new investment activity.

That said, if that saving is in a government sponsored account then that return of funds to the government, which is what saving in this way does, achieves the apparent holy grail of government funding, which is of it balancing its cash flow, with tax receipts and borrowing equating to tax spending. The apparent benefit of saving in government sponsored accounts, which is sometimes called funding the national debt, is demonstrated as a result. If those accounts are in use, and properly promoted, no government should ever be able to claim that its books do not balance.

The second and subsequent diagrams expand this basic idea to consider various commonplace aspects of current government financing.

Diagram Two demonstrates that there is a cost to both the government and savers as a result of the government not encouraging people to save directly with it. Savers pay fees to financial market participants when they could avoid these by saving directly. The government, by not appropriately promoting National Savings and Investments (NS&I) might well pay too much for its borrowing. At the same time a myth of market dependency is created. None of this makes sense.

Diagram Three makes clear that there is a very real cost to then government from tax abuse. Since 2010 this might have amounted to £435 billion, or thirty per cent of total government borrowing over that period. Given that the tax gap is likely to be considerably underestimated by HM Revenue & Customs, this cost might be much higher than that. Failing to invest in HM Revenue & Customs directly fuels the growth of government borrowing. Again, this makes no sense.

Diagram Four considers the consequences of quantitative easing. What it shows are three things.

The first is that when quantitative easing is in use it does, in effect, deny consumers the choice of saving in government sponsored savings facilities, with them being forced instead to use alternative commercially available accounts. This is sub-optimal when it is known that cash-based deposits with banks do not fund loans, and therefore do not create new investment in the economy, whilst financial market based saving is almost entirely related to speculative activity, and not new capital creation. As such, this diversion of funds denies funding to the active economy.

Simultaneously, and secondly, because governments-based savings accounts are withdrawn from the economy, pressure from the supposed incurrence of government cash-flow deficits arises as a result. New money must necessarily be injected into the economy as a consequence, which is represented by an inflation in the central bank reserve accounts. These sums are then, in turn, reflected in an increase in savings in financial services sector savings accounts, with all the consequences noted above. Given that interest is paid on the central bank reserve account balances this does not make sense.

Thirdly, although it is not explicit within the diagram, the obvious conclusion can be drawn that if it is desirable to increase the quantity of government created money in the economy, and there have clearly been occasions when that is the case, doing so by increasing direct spending into the economy without seeking to recover those sums, at least for a period of time, through taxation would be a much more direct and effective method of doing so as this boosts the active economy in a way that boosting financial services sector saving does not. The government should run an overdraft with its central bank as part of fiscal policy, in other words, and avoid quantitative easing as a result.

Diagram Five incorporates pension saving into the flows. This is appropriate because the cost of subsidising these savings in tax terms might be around £70 billion a year according to the analysis presented in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024. Given this exceptional cost it is important to understand the consequences of this, which Diagram Five demonstrates.

The consequence of this subsidy is that pension savings and the additional tax refunds provided to boost them by the government flow out of the active economy and into the financial services sector where these funds are lost from use in that active economy for the reasons noted above. As a consequence, the government does either have to seek savings from the financial services sector to balance its cash flows, which makes no sense when it would be much better for those savings to be placed with it individually by those whom that sector serves, or it has to run increased cash flow deficits, which it will not do. The result is that this tax subsidised diversion of savings from the government to the financial services sector, coupled with the government’s own illogical refusal to run an overdraft in its Ways and Means Account with the Bank of England, creates the appearance of the dependence by the government on funding from the City of London when no such dependence exists.

Since 2010 it is likely that the total cost of tax subsidies to pensions, and so to the financial services sector of the economy, has amounted to approximately £800 billion whilst so-called government debt has grown by £1,450 billion. The relationship between the two is not coincidental.

Finally, Diagram Six looks at what might happen if the government was to reform the tax reliefs associated with both ISA and pension savings as recommended in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024. It demonstrates that if the tax relief made available to subsidise savings had conditions attached to them so that some (in the case of pension savings) and all (in the case of ISA savings) were required to be used to provide capital for investment in new infrastructure projects supporting a climate transition then significant sums, which the TWR suggests could be more than £100 billion a year, could be made available for this purpose, with those funds then being returned from savings into the active economy where they would begin the process of creating fiscal multipliers all over again.

In other words, this simple change to the tax incentives attached to savings could fundamentally alter the funding available to tackle climate change in the UK whilst simultaneously providing a strong positive fiscal multiplier effect from doing so, which the current tax relief does not. In fact, current tax reliefs have a negative multiplier effect in this regard, because they result in the withdrawal of funds from use in the active economy by diverting them into financial speculation or cash deposits, neither of which result in new capital formation. It is for these reasons that these changes to the tax rules associated with savings products are promoted in the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

Putting these various points together, what the Taxing Wealth Report 2024 seeks to do is:

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects resulting from government spending of new funds into the economy.

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects arising from the best choice of tax rates, meaning that those on low incomes should have low overall effective tax rates and that those on high incomes should have higher overall tax rates, which delivers this outcome.

- Provide reason why the government should encourage more direct saving in the savings products that it makes available for this purpose that are usually collectively called the national debt, but which might be better described as national savings.

- Explain the cost of tax abuse to the government in terms of excess borrowing that it has to take on as a result, which has amounted to not less than £435 billon since 2010.

- Demonstrate the cost to the government of pension saving subsidies that might have cost £800 billion since 2010, or fifty-five per cent of the so-called national debt incurred in that period.

- Maximise the fiscal multiplier effects from saving so that new investment can be generated from this activity which has not been the case for many decades in the UK, with a resultant boost to our economy, employment, and growth as well as to the creation of the capital infrastructure needed to address climate change and other social issues in the UK.

Footnotes

[1] N/A in this version

[2] Multiplier effects measure the amount by which national income is increased or decreased as a result of additional spending within an economy. If a multiplier effect is greater than one then the additional spending produces an increase in income of greater than its own amount, and vice versa.

[3] See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/glossary/C/#central-bank-reserve-accounts for an explanation of these the role of these accounts.

[4][4] See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/glossary/B/#base-money for an explanation of base money

[5] https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/xl5bo4as/jul-sep-2023.pdf

[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/measuring-tax-gaps/1-tax-gaps-summary

[7] https://obr.uk/download/public-finances-databank-november-2023/?tmstv=1707402181

[8] See https://taxingwealth.uk/2023/09/19/the-taxing-wealth-report-2024-the-uk-needs-better-estimation-of-its-tax-gap-to-prevent-the-illicit-accumulation-of-wealth/

[9] See the letter establishing the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility (APF) in which it was made clear that a) the Bank of England would act under direction from the Chancellor of the Exchequer and b) the Bank of England would be indemnified for any gains and losses that it made as a result of undertaking activity on behalf of HM Treasury and c) note the fact that as a consequence the accounts of the APF are not consolidated into those of the Bank of England because it is not a subsidiary under its control. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2009/chancellor-letter-290109

Labour is claiming that £28 billion of investment in climate change a year is not possible. But that’s not true. That’s Starmer’s choice.

I posted this thread on Twitter this morning:

Labour says it cannot now afford to spend £28 billion a year to deliver the investment in the climate transition that we all know we need. Let’s leave the politics and even the climate bit aside. Let me just look at the affordability bit. A thread….

Labour announced its green investment plan in 2021. And nothing much has changed since then, to be candid. For example, by the time it gets to office inflation will have been and gone.

Growth will also be non-existent then, as it was in 2021. Borrowing will be high, as it was back then. But government borrowing costs will be tumbling this year. They may not be at 2021 levels. But they really won’t be an obstacle to spending.