economic justice

Capital gains should be subject to the same rate of tax as income

I have posted this video on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok this morning:

The transcript is as follows:

One of the proposals that I make in the Taxing Wealth Report is that capital gains should be taxed at the same rate as income.

Capital gains are the profits that people make from selling land and buildings, or pieces of art, or stocks and shares, or, anything else of that sort that, by and large, wealthy people own.

And I can't see any reason why they should pay a lower rate of tax on the money that they make from this activity than you and I do on working for a living. But that's what happens now. By and large, they pay tax at half the rate they would do if they were working to make the same amount of money.

That's unfair.

It's also very costly. We could raise at least £12 billion of extra tax revenue a year. If we equalise these two rates, do you think we should do that? If so, I've got a suggestion to make to you. Please tell Rachel Reeves, or send her a letter, or send her an email, or tweet her and say something like this:

Rachel Reeves

Why is it that the Labour Party will not charge capital gains at the same rate as income?

Nigel Lawson did when he was Conservative Chancellor. Why won't you?

And why don't you think that's fair? I do, because it would raise enough money to help fund the programmes that are essential to restore our public services.

Best regards, etc

That's a positive action you can take to make a difference as a result of reading the Taxing Wealth Report 2024.

As is apparent from that transcript, the video includes the suggestion that those who watch it might want to contact Rachael Reese and ask why it is that she is willing to tolerate this type of justice when correcting it would provide essential funds that would permit Labour to spend more on essential public services.

I am particularly curious to know whether those here think that making such a call for action is a good idea.

It takes considerable inability to get so much, so wrong, so often, but the Bank of England has achieved it.

As the Guardian reports this morning:

[Retail] industry figures show prices rose at an annual rate of 1.3% in March, down from a rate of 2.5% in February – the slowest pace since December 2021, according to the latest monitor from the British Retail Consortium (BRC) trade body and the market research firm NielsenIQ.

Non-food inflation dived to just 0.2% from 1.3% in the previous month, while food inflation fell to 3.7% from 5%.

I suspect that most people will see this as good news. Prices are still rising, as the government and most economists would desire, but at a much slower rate now. I have three thoughts.

Firstly, the risk of deflation now looks to be real. If prices of non-food items continue to tumble, there are real signs of a dramatic shortage of demand within the economy that might make this possible. There are always problems when this happens because deflation easily tips over into ever-deepening recession. Those problems would be best avoided. Easing of monetary policy, to make sure that prices only stabilise, rather than fall too significantly, would now seem to be a priority.

Secondly, given that energy prices are also falling, these price falls suggest that the continuing downward trend in overall inflation is very likely.

Thirdly, in that case, there is one set of prices that are now very clearly out of line with the whole economic environment. These are rent and mortgage costs, both of which are heavily influenced by the Bank of England's interest rate policy. Whilst it is undoubtedly true that financial markets are now pricing some expectations of declining interest rates into their mortgage offers, there will be no significant move until the Bank of England cuts their rate, and the same will be true with regard to the pressure on rent increases.

The result is that real household costs, not necessarily properly reflected in inflation calculations, are still rising in too many cases, and this is the likely cause of the downward pressure on prices elsewhere, which is now reaching the worrying stage where deflation could result. All the indications are that there is an urgent need for a cut in interest rates of a significant amount very soon. The problem is that nothing of that sort is currently even being hinted at as a policy option from the Bank of England.

Putting these three factors together, I continue to believe that if any organisation has mismanaged this crisis, it is the Bank of England. They raised interest rates when they had no reason to do so. Now, they are refusing to reduce rates on a timely basis when there is every reason for them to fall because the economic harm that they are creating is significant.

It takes considerable inability to get so much, so wrong, so often, but the Bank of England has achieved it.

Most worrying of all, though, Labour has committed itself to the perpetuation of the Bank's incompetent control of the economy. In that case, there may be trouble ahead.

Smelling the coffee

As the FT noted in its Lex column yesterday:

First chocolate, now coffee — the supply of modern life’s necessities is being squeezed by a changing climate. Extreme temperatures and droughts in south-east Asia, home to the world’s second- and third-largest producers of coffee beans, have led to lower harvests.

But given that this was the FT they went on to note:

Falling bean supply has implications not just for our daily lives but also for company earnings.

Blow the impact on those growing the beans and the disruption to their lives: what matters is falling corporate earnings, not global heating and the impact it has on working people.

That said it did note that those impacts are not likely to improve, albeit still within the context of corporate earnings. As they noted, a heatwave in Vietnam, the world’s second-largest bean producer, has cut production thereby maybe 20%, with much the same happening in Indonesia, which is also a major producer. Coffee prices are up 50% as a result. And this is likely to continue. Despite the price increases, climate change is making coffee too unreliable a crop to grow in south-east Asia, and farmers are pulling out.

I have never hidden the fact that if I have any form of addiction (and I really don't think I have), then coffee is the closest thing that I get to it. I consume more than my fair share of the world's coffee beans per day, I am sure.

At present, the price of coffee has not changed enough to really impact my consumption, but that does not mean that it might not at sometime in the future.

I often wonder when it will be, and what it will be, that brings home the reality of the change in consumption patterns that climate change is going to demand of us. I really do not know. But, what I'm sure about is that this will happen.

What I also know is that in a great many ways, this cannot happen soon enough: we need to really appreciate precisely what we are doing to our planet to understand the necessity of change. Rationally, we should already be there. Emotionally, we are not, so that we pretend nothing is happening. The sooner that we can close that gap so that we can let go of what is no longer possible, and imagine what might be, the better off we will all be in the long term.

Just suppose we tried to meet needs? What might happen?

A new commentator on this blog named Tony Wikrent made an interesting comment yesterday, saying, when discussing the purpose of economics:

”Many subscribe to Lionel Robbins’ definition of economics as the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends”

This is where economics goes wrong – right from the beginning. The actual history of Understanding this would radically shift the what economists emphasise. Financial markets and prices would become much less importance, and the creation of science and new technology would become paramount areas of inquiry.

Robbins, whose overall contribution to economics was not nearly as important as I think the London School of Economics like to claim it to be, undoubtedly heavily influenced economic thinking with his 1935 book in which he offered the above suggestion. That idea was taught to me in the 70s. It is still commonly noted. Ask ChatGPT what economics is about and it suggests:

Economics is the social science that studies how individuals, businesses, governments, and societies allocate resources to satisfy their wants and needs, given scarcity. It analyzes production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, as well as the behavior of markets and economies.

Scarcity is the condition that requires economic choice, apparently, based on a search of the web as a whole. The idea remains in common use then, in itself constraining us all. It was, apparently, Robbins maxim that human beings want what they cannot have, and that notion need not be true, meaning it did not have the power he gave it.

In the 1930s, when Robbins wrote, I am aware that one of my grandfathers earned 30 shillings a week (£1.50) and lived in a tied cottage in a state of both considerable insecurity and poverty. My mother’s descriptions of that upbringing have influenced me, without a doubt. In that situation, then Robbins was to some degree right; human beings did want what they could not have.

But, as Tony Wikrent implies, Robbins thinking (both economic and social) was decidedly static. His presumption was that what was scarcity was a permanent state in which the economy must exist. Post-war development showed that this need not be the case. .

Vastly better housing became available. Incomes rose. The post-war consensus delivered prosperity to vastly more people, me included. The problem of scarcity was not solved, but it altered radically. Three themes became apparent.

The first was that it became possible that we could meet need. It was, and remains, possible for us to ensure everyone in the world could enjoy a life where their needs are met. I am not saying that would be easy. I think it could be done.

Second, that fact did not solve the problem of scarcity. Those with the ability to solve the problem of unmet need chose not to do so. Scarcity with regard to need was imposed instead. It was no longer inevitable, but it continued to exist, nonetheless.

Third, the reason why need was not met was because those with the means to do so chose, or rather were persuaded, that satisfying their wants was a higher goal than was the meeting of the needs of others.

When Robbins wrote in 1935 the whole field of marketing, and the manipulation of human perception that it involves, was virtually unknown. Advertising did, of course, exist. But marketing is quite different. It seeks to create wants where none existed, and that activity did not become commonplace until the 1950s. The imposition of continued scarcity was a necessary condition for marketing’s success. Innovation might have created the means to address all needs, but the reality was that it was instead primarily directed at meeting previously unknown wants.

Does that mean that I disagree with Tony Wikrent? It does not. The point he makes is powerful, and appropriate. It does, however, need to be framed and that framing is to be found in the choice that supposedly free markets have made with the power to create technology that we have discovered.

That power has been used to achieve three outcomes. One, very obviously, is consumption beyond the physical constraints that the planet can sustain. As a result, we have the climate crisis.

Second, this power has been used to concentrate wealth in the hands of a few. Technology in innovation has, when subverted to private purpose, and when coupled with the abuse of artificial legal constructs like patents and copyrights, been used to create market power that eliminates competition, suppresses further innovation and delivers massive inequality within society.

Third, as a result, innovation has begun to destroy its own potential to meet either needs or wants as the preservation of the wealth of a few is deemed a higher-order priority than meeting the needs of an increasing number of people, whilst it also destroys the very markets that supposedly fostered its creation.

To put it another way, the whole purpose of market-based economics has become the prevention of the meeting of needs whilst simultaneously creating the means for an increasingly smaller number of people to consume to excess way beyond any conceivable measure of human requirement.

The problem for this economic model is that it is unsustainable. As more and more people are driven towards economic desperation, which is very obviously happening at present, the social acceptability of this form of economics is collapsing. Simultaneously, the excessive use of natural resources that it requires is becoming evermore apparent. Neither, by themselves, would be sufficient to bring this system down. Together, they create a situation where that is likely.

What happens then is the question to ask? This is where I think Tony’s comment is very relevant. Suppose that the whole purpose of industrial and agricultural development was to become the overcoming of the scarcity of resources. Could we find the food to feed the world, the water to sustain it given global heating, and the means of shelter, free from risk, where people might enjoy secure lives of reasonable comfort, free from fear? I think we could. But it does present the most massive challenge to a hierarchy of innovation and power that largely ignores need at present and instead presumes that the accumulation of excessive wealth for a few is the goal of society.

Gordon Brown’s answer to poverty in the UK is to appeal to charity. When Labour looks like it will have a massive majority soon that is pathetic.

Gordon Brown, the former Labour Prime Minister, had an article in the Guardian newspaper yesterday that plumbed new depths for the Labour Party.

Brown acknowledged that the UK has a poverty crisis, with vast numbers of people having insufficient income to meet their needs. As he noted, one million children now live in what might properly be called destitution, because absolute poverty does not seem an adequate description.

Having wrung his hands over this, and inevitably seeking to blame the Tories, he claimed to have a plan to address the issue.

There were two parts to this plan. In the first, he suggested a tiny pruning of the amount of interest paid by the Bank of England to the UK’s commercial banks each year on the deposits that they supposedly hold with our central bank. These sums actually represent the new money supply created by the Bank of England on behalf of the government during the 2008/09 financial crisis and 2020/21 Covid crisis, which the commercial banks did, as a result, do literally nothing to earn.

Approximately £40 billion will be paid in interest on these accounts this year. Brown suggested that between £1 billion and £3 billion of this sum might be redirected towards addressing extreme poverty in this country.

Having made this totally feeble gesture when the opportunity to do so much more with this wholly inappropriate enrichment of bankers was available to him, he then added his second suggestion. He did not, as any reasonable left-of-centre person might have expected, suggest that companies and people with higher levels of income might pay more tax to address the inequality that we now face as a country. Instead, he appealed to their charitable instincts and suggested that if only they donated a little more to food banks, the whole problem might be solved.

I have already suggested today that Labour’s frank admission that it does not intend to do anything about the power of the private sector, or the inevitable fact that the private sector does not allocate rewards appropriately within society, is recognition on its part of creeping fascism, about which it very obviously has no intention of doing anything.

Brown reinforces my opinion that Labour has altogether given up on challenging inequality, the power of the private sector, and the power of private, wealthy individuals within our society. Instead, it does now seem that it will tolerate any outcome that the market now dictates, however, undesirable that is for the people of the UK as a whole.

You could describe this as Labour giving up on its fundamental purpose, and you would be right to do so.

You could alternatively suggest that this is Labour tolerating the creep of fascism into our society, and again I think you would be right to do so, although I am sure that Labour itself would disagree. But, when it is doing nothing to stop that advance of fascism, what right have they got to do so?

As I have said before today, and will no doubt be saying many more times over the months and years to come, I have shown that none of this is necessary. The Taxing Wealth Report demonstrates that the money required to tackle the problem of poverty in the UK could be raised by simply reforming some of the existing taxes within this country. This would be easy, especially for a party in power possessed of a massive majority, which Labour is likely to have. Quite literally, nothing could stop them from reshaping the way in which rewards are shared within our society for the benefit of that society as a whole.

If Labour are not willing to do that with the power that they are likely to have then what are they for? Apart from enabling fascism, that is.

The stories we tell each other about the economy in which we live are more important than the data we collect about it

With politicians, taking an Easter break, inspiration has to come from elsewhere this morning. I am returning, in that case, to the article by economics Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton on the IMF website, which was entitled "Rethinking my economics".

I admire Deaton for having the courage to write this article. That is what it takes to admit that you might well have been wrong throughout a large part of your career, which is what he appears to be doing.

There are, I think, three themes. The first is this one:

Power: Our emphasis on the virtues of free, competitive markets and exogenous technical change can distract us from the importance of power in setting prices and wages, in choosing the direction of technical change, and in influencing politics to change the rules of the game. Without an analysis of power, it is hard to understand inequality or much else in modern capitalism.

Unsurprisingly, I agree. Political economy is all about the influence of power on the allocation of economic resources. Most economists assume that this is not a problem by suggesting that everyone has equal access to capital, which equal access can be equated with an assumption as to there being equality of power when they undertake their spurious calculations. The difference in worldview is decidedly stark. One reflects reality, and the other does not. It is about as blunt as that. It would seem that Angus Deaton has now realised that. That matters. As I argued earlier this week, power and its abuse are what really matters when it comes to the creation of economic justice.

Then there is the spurious economic argument for efficiency, which we hear expressed all the time as the demand for more productivity. On this Deaton says:

Efficiency is important, but we valorize it over other ends. Many subscribe to Lionel Robbins’ definition of economics as the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends or to the stronger version that says that economists should focus on efficiency and leave equity to others, to politicians or administrators. But the others regularly fail to materialize, so that when efficiency comes with upward redistribution—frequently though not inevitably—our recommendations become little more than a license for plunder.

Again, I agree. The vast majority of the demands for productivity made within the economy are intended to reduce the level of labour input into the production of goods and services, whilst at the same time increasing the return to the rentier who has exploited the natural resources of the world to deliver the material component. Almost without exception, this becomes the license for plunder to which Deaton refers.

That said, I do of course know that there are exceptions. But, to refer to his previous argument on power, differentiating the two by undertaking an analysis of power is critical if we are to understand the reality of the demands for efficiency made within our economy. By no means all demands for efficiency are benign, and many are far from it.

Deaton added this when discussing this issue:

Keynes wrote that the problem of economics is to reconcile economic efficiency, social justice, and individual liberty. We are good at the first, and the libertarian streak in economics constantly pushes the last, but social justice can be an afterthought. After economists on the left bought into the Chicago School’s deference to markets—“we are all Friedmanites now”—social justice became subservient to markets, and a concern with distribution was overruled by attention to the average, often nonsensically described as the “national interest.”

I am not sure what to add, apart from 'quite so'.

Let me then note the final issue he mentions that I want to highlight here, which is:

Humility: We are often too sure that we are right. Economics has powerful tools that can provide clear-cut answers, but that require assumptions that are not valid under all circumstances. It would be good to recognize that there are almost always competing accounts and learn how to choose between them.

I know he also refers to ethics and empirical methods in the note that he wrote, but I feel that both can be summarised in this single paragraph on humility.

If we are to make choices between competing accounts, then we necessarily need to have an economics that is ethical. In a very real sense, there is no other choice.

That, as Deaton himself noted, requires that economics rethink its use of empirical methods that necessarily impose an artificial worldview on economic analysis so that economists might undertake their existing form of mathematical interpretation of the incomplete and flawed data that they collect, which they do, however, presume to be value free in almost all the exercises that they undertake.

As I have always argued, the stories that we tell each other about the economy in which we live are more important than the data we collect about it because they provide the framework within which any information is interpreted. It would seem that Deaton now agrees.

I call that progress, except for the fact that about 92% of the world's living economists are probably now in disagreement with him now. We will just have to make progress, one step at a time.

You can’t say MMT does not work because you think Scotland will be a failed state after independence

This tweet was posted over the weekend:

“I’m the Fox Mulder of MMT. I want to believe, but there’s a thing called the current account constraint...”@MkBlyth, professor of internatonal economics at @BrownUniversity savages Modern Monetary Theory at #Scotonomics festival. pic.twitter.com/XotdMBZh1Y

— Ian Fraser (@Ian_Fraser) March 23, 2024

The interview was by Karin van Sweeden with Prof Mark Blyth of Brown University in the USA, where he is professor of international political economy.

I happen to know both participants, although not well in either case.

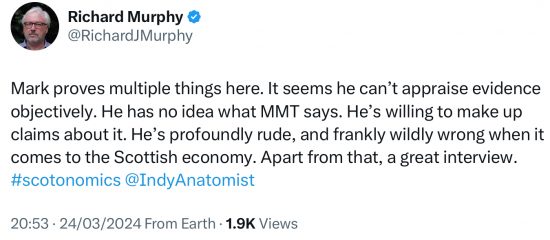

I was infuriated by Mark’s comments and posted this last night in response to a typical comment supporting his position:

Mark’s claim was that he wants to believe in MMT but can’t because of the balance of payments problem that he claims it ignores. He summarised his argument on three ways.

First, he said Argentina has a sovereign government and currency and it has not avoided a debt crisis. This totally ignores that fact that Argentina is a still developing economy and is treated as such by much of the world. It also ignores the fact that it borrows in dollars, when MMT very strongly advises no country should borrow in any currency but its own. And ignores the fact that it has to do so because of its decidedly rocky history of political instability. To suggest that Argentina and Scotland are in the same place is, to be polite, crass in that case. Mark would have told any student of his that, I am quite sure. In that case to make the comparison in a public debate really was unwise.

Then he claimed MMT says a government can default on its debts, print some more money and carry on as before. This suggests Mark has never easy anything written about MMT. Anyone who is serious about it has never said such a thing, although no doubt some uninformed enthusiast on the web has. Mark should really be able to tell the difference, and not make such an absurd claim. It’s is unbecoming of a person with some stature to make claims that are very obviously untrue about an opponent’s arguments. Why is it that he and others think it acceptable to do so about MMT?

Third, he then utterly belittled Scotland, saying it had nothing to sell the world and as such its currency would be utterly worthless. As such he claimed that no one would accept a Scottish currency and as a consequence, the MMT argument that Scotland should have its own currency had to be wrong. This argument is utterly absurd, and it is easy to demonstrate why.

If, as Mark claims, Scotland would have nothing to sell in the world after independence (and that was his specific claim), then it follows that his claim that Scottish debts would have to be settled in either US dollars or sterling is the most incoherent position that he could adopt. As a matter of fact, if his argument is true, Scotland would have no means of acquiring those currencies after independence as, he claims, it would have nothing to sell in international markets, which is the only way to acquire them. It would, therefore, automatically default on all debts denominated in pounds or dollars because it would not have them.

On the other hand, it would never need to default on debts denominated in Scottish currency because it could always create that. So, rationally, anybody trading with Scotland in this situation would have their risk reduced by trading in a Scottish currency rather than in pounds or dollars, because at least then they were likely to be paid, which is a much better than not being paid at all, which is the position that he would apparently prefer.

Far from being smart, as he obviously thinks he is being, Mark is as a result actually putting forward the worst case argument that he could create for Scotland given the assumptions that he makes by suggesting it use a foreign currency. In the situation he describes only a Scottish currency could work for it.

But let’s also be honest and say the argument he makes is crass in any case.

Firstly, Scotland is an old country, with an old democracy, and a competent civil service, backed by a legal system with centuries of history behind it, which system is recognised to be stable and enforceable. It also, quite critically, has a strong and functioning tax system, which would, under an independent government, be capable of collecting even more tax than it does at present, and that is the true basis for the foundation of the value of a currency. In other words, every assumption that he makes about Scotland, which can be summarised by saying that he thinks it would be a failed state, is completely wrong.

It is also, very obviously true that his claim that Scotland will have nothing to sell after independence is quite absurd. Let’s ignore the fact that Scotland has, overall, over many recent decades on average run a trade surplus and instead note that Scotland has a greater capacity to create renewable energy in proportion to population than any other country in Europe, and this has to be the strongest foundation for its prosperity that it can have. I should also add that it has a lot of fresh water as well, and that is going to be an incredibly scarce commodity in the world, sometime soon. It also helps that it will have a very near neighbour who will be short of both. In other words, Mark’s claim that Scotland would have nothing to sell is ridiculous. There is in fact every reason to think that the Scottish pound will trade at a higher value than the English pound after Independence, for the reasons I note.

So let’s leave MMT aside for a moment, because Mark has clearly got no understanding of it. Instead let me just make the obvious point that what Mark said was that he thinks Scotland is too wee, too poor and too stupid to be independent, which is a standard Unionist argument that is both party patronising and downright rude. His claim that Scotland cannot pay is not in that case related to a currency question. It is related to his belief that Scotland will be a failed state.

MMT does not prevent states failing. Nor does it create failed states. All it does is describe how money works, more accurately than any other economic model that I know of. Doing so, it roots itself in reality. Indeed, no model is more rooted in the actual capacity of an economy than MMT because it recognises that physical capacity as the real constraint on activity.

MMT does, in that case, have nothing to do with then argument that Mark Blyth presented, which was based solely on wild comparisons between Scotland and Argentina and the absurd suggestion that Scotland creates nothing of value. Of course if you start from false assumptions, as Mark did, you get to absurd conclusions, as he did. But to then claim MMT had any part in that is absurd. It did not.

If an undergraduate student had offered the analysis Mark Blyth did they would have deserved to fail. It was embarrassing to see him make such a fool of himself. The SNP have appointed him as an adviser in the past. I sincerely hope they do not do so again. Someone who so clearly despises the country he left some time ago quite as much as he does really has no place helping the independence movement, in which he clearly has no belief.

Will Hutton’s praise for Rachel Reeves’ Mais lecture is itself a pretty depressing foretaste of the disaster that Labour will be.

Like many, I was confused by Will Hutton’s arguments in The Observer today, in which he argued that Rachael Reeves has given Britain “the plan for economic lift off”. Unsurprisingly, I disagree with him.

Let me summarise my argument at the outset. I think Will Hutton is looking for a job. I cannot explain what he is saying in any other way.

Then let me move to the detail. Will is arguing, as I can see it, three things.

First, his suggestion is that those who have tried to impose policy on the economy have always got things wrong. He quotes Polanyi, who he interprets as saying that it was the imposition of centrally dictated policy that gave rise to the extremist backlashes of the 1930s. As a result, he seems to be applauding her for backing away from that central planning. Doing so, he ignores his own past demands, and what most would think to be the critical economic social democratic role of any government, which is to constrain the errors, excesses and inappropriate directions of market economics. Perhaps he is, however, revealing that he really has been a disciple of Hayek all along, whilst also revealing that he thinks she is. I really can’t work out what else he is trying to say.

Then, entirely paradoxically, he endorses her claim that this is an inflection point where what he describes as “a new productivist economic paradigm is emerging” which he argues is “vital for economic growth and social cohesion through higher public investment, an active industrial policy and quality public services.” Anyone who can reconcile this second argument with his first, noted above, deserves a prize.

Third, he then argues that adopting Jeremy Hunt’s fiscal rules, as she is, will not in any way constrain her ambition to deliver this plan for growth. His reasons for saying so are, as far as I can work out, twofold. First, he seems to suggest that the rule is just for show because the figures can always be fudged to make it work. This might be a frank recognition of reality, but it does not constitute either a fiscal plan, or economic sense. Then, the paradox continues, because having firstly condemned central planning, and then praised it, he then seeks to reconcile his positions and the use of this fiscal rule by suggesting that the job of government will, in Rachael Reeves opinion, be to direct the way in which private capital will be invested, because the government is not going to make any available. In that way the fiscal rule is upheld but the desired growth is delivered in accordance with a plan for which Reeves can then take credit. Quite why he thinks that this might be possible he does not say, because very obviously Rachael Reeves does not know either, if that is what she really thinks.

But then, there’s a great deal that Rachael Reeves does not know or say. She does not say how she will tackle poverty. Nor has she got a plan to save local government. The NHS can only be presumed to be up for sale. There is no money for education. Devolution, as ever, got no proper mention from Reeves. And apparently, all this can be ignored because the right wing press would criticise Reeves if she did discuss such issues, so Will Hutton thinks she need not do so.

I am sure, as I mentioned at the outset, that Will Hutton had a reason for writing this article, but the piece is itself profoundly confused in an attempt to endorse Reeves’ own incoherence. If this is indication of the current level of centre-right thinking around Reeves (where she, herself, is located on the political spectrum) it is a pretty depressing foretaste of the disaster that Labour will be.

Growth in the economy creates wealth that never trickles down, but is what Labour says it wants. What is it going to do for the 12 million people in absolute poverty in that case?

The Guardian reports this morning that:

Overall, during the year [2022-23] 12 million people were in absolute poverty [in the UK] – equivalent to 18% of the population, including 3.6 million children – levels of hardship last seen in 2011-12 after the financial crash.

Growth will not solve this. We know that wealth never has and never will trickle down.

In that case, nothing will change under Labour without radical reforms to benefits, minimum wages, worker rights, trade union rights, and the probable creation of wage councils. So far, I am not hearing nearly enough about those reforms, which instead already appear to be at risk of being watered down.

We do, however, keep hearing from Labour about the need for growth.

As I argued yesterday, this is the wrong policy for this era in history. Meeting everyone's needs within sustainable limits should be our priority now. Unless that change happens, 12 million people will continue to live in absolute poverty in the UK.

Is that what Labour wants?

The UK does not have a national debt but does instead offer a range of national savings products

My evidence to the House of Lords Economic Affairs committee on the sustainability of the UK’s national debt is now available on the parliamentary website;

The evidence is as follows:

PROFESSOR RICHARD MURPHY – WRITTEN EVIDENCE SND0016 – SUSTAINABILITY OF THE UK’S NATIONAL DEBT INQUIRY

Introduction

- This submission is made in response to the UK parliament’s House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee call for evidence, asking the question ‘How sustainable is our national debt?’ https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/175/economic-affairs-committee/news/198891/economic-affairs-committee-launches-new-inquiry-on-the-sustainability-of-the-uks-national-debt/

- This evidence is submitted by Professor Richard Murphy, Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School and director of both Tax Research LLP and Finance for the Future LLP. In all those roles I have worked on the accounting for and sustainability of the UK’s so-called national debt.

Summary

- In its early paragraphs, the Committee notes that the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility stated in 2023 that “the 2020s are turning out to be a very risky era for public finance”. In this submission I argue otherwise, suggesting that:

- The UK does not have a national debt but does instead offer a range of very popular national savings products and also has national equity that is not yet recognised in the nation’s accounts.

- All of these are sustainable in their current forms and the holders of national savings products from gilts to premium bonds and NS&I accounts most definitely do not wish for the return of their funds to them.

- The cost of servicing these savings accounts and the national equity is under the control of the government and if it is currently considered excessive then that is as a result of its choice to make it so as a result of the imposition of artificially high interest rates in an unnecessary attempt to control inflation.

- The so-called national debt as stated by the Office for National Statistics is overstated in value by approximately £1 trillion.

- National equity capital exceeds £700 billion.

- The ratio of so-called national debt to GDP is not useful as a tool for economic management, not least because the figure for national debt now used is seriously overstated as a result of mismeasurement by the Office for National Statistics.

- As a result, what is required is that we properly understand the nature of the nation’s finances, its income and expenditure and balance sheet and to then use that understanding to attract the additional funding required to fund the investment in the UK that is now required which can only be delivered by action on the part of the government.

Submission

- Although the call for evidence refers to the sustainability of the UK’s so-called national debt this is inappropriate. The UK government does not have a national debt. Instead, it provides savings facilities for banks, pension companies, life assurancecompanies, foreign governments, and, if they wish, individuals. Those savings facilities include Treasury bonds, or gilts, Treasury Bills and the products offered by National Savings and Investments (NS&I). The balances on NS&I accounts have risen as follows since 1998, providing evidence in support of the suggestion that these facilities are attractive to consumers:

Source: Office for National Statistics public finances databank

- Government provided savings facilities have increased in significance since 2000, when the management of the so-called national debt and government cash requirement was transferred from HM Treasury to the quasi-independent Debt Management Office[1].

- There is no reason why the arrangements in use to manage cash requirements prior to 2008, when it was normal for the government to borrow from the Bank of England using its Ways and Means Account facility rather than to necessarily borrow from financial markets to balance cash flow requirements, cannot now be used again. This is most especially the case since Brexit and the removal of Maastricht Treaty restrictions on the use of his arrangement[2].

- It is, as a result, apparent that the scale of the UK’s so-called borrowing from financial markets is a matter for it to now decide upon, and not for markets to determine. The question of the UK’s debt sustainability is not relevant as a result.

- Importantly, the UK government can, instead of accepting liability to third parties for funds deposited with it (which is how the existing so-called national debt might be most appropriately described), choose to create money to fund its own activities, leaving these balances on loan account with the Bank of England whenever it wishes. This is, in effect, what the quantitative easing process has done, although to meet the requirements of the Maastricht Treaty[3] that process has been heavily disguised[4].

- The interest cost of the savings products that the government supplies is under the government’s own control. This is clearly the case with NS&I products, but all its other savings products are also heavily influenced by the Bank of England base ratewhich the government could take control of at any point of time if it so wishes by changing the provisions of the Bank of England Act, 1998[5]. Brexit also provides it with the freedom to do this. The cost of interest on the central bank reserve accounts could also be brought under central government control in the same way.

- The U.K.’s national debt has been sustainable since 1694 when it was first created[6], and barring the issue of 3% War Bonds in 1914[7] has never suffered a problem with product placement, with all redemptions also always being rolled over without difficulty, meaning that questions about sustainability of the debt appear to be somewhat misplaced. Anything that has lasted that long, and often at supposed ratios to GDP much in excess of those now recorded, is not a matter of concern.

- The current ratio of so-called debt to GDP is in historical terms low. The current level of so-called national debt, despite what is being claimed, is not unsustainable as the evidence from history makes clear.

Source: https://articles.obr.uk/300-years-of-uk-public-finance-data/index.html

- The ratio of national debt to GDP as reported by the ONS is, in any event, meaningless and not comparable with data in the time series noted above for periods prior to 2010 because of the impact of quantitative easing. This is because it remains the case that more than £700 billion[8] of UK government bonds are still owned by a notional subsidiary of the Bank of England[9] that is actually under the effective beneficial control of HM Treasury[10]. Similar gilts in existence, but not in circulation, owned by the Treasury’s Debt Management Office are excluded from all figures for national debt[11], but those beneficially owned by the Treasury via the Bank of England, and so similarly out of circulation in the economy are included in the figure for the national debt. The disparity is glaring, obvious, and irreconcilable. The national debt is overstated by more than £700 billion or more as a result because as a matter of fact, the government cannot owe itself money, which cancellation is confirmed by this accounting being adopted within the UK Whole of Government Accounts[12] which are prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards.

- The national debt is also overstated by almost £300 billion because of the Office for National Statistics’ claim that there is aso-called Bank of England contribution towards that debt for which no matching liability exists in the audited account of the Bank of England. The figure in question represents assets that the ONS arbitrarily refuses to accept the existence of when estimating the national debt. The total sum in question cannot be categorised as debt because there is no identifiable person to whom it is owing. The problem arises because the Office for National Statistics does not use double-entry accounting when estimating the national debt.

- In combination, the matters referred to in the last two paragraphs suggest that the so-called national debt is £1 trillion less than the Office for National Statistics currently estimate as a consequence[13].

- The biggest threat to the so-called sustainability of the UK’s national debt is the notional resale of bonds bought by the Bank of England during the course of the quantitative easing era by that Bank. They are doing this with the aim of supporting the high interest rates that have been artificially imposed upon the UK economy in an unnecessary attempt to tackle inflation which has instead given rise to a risk of recession. This programme, the detail of which was announced[14] the day before Kwasi Kwarteng’s ill-fated budget[15] in September 2022, was the actual cause of the pension liquidity crisis that emerged over the following weekend, which in turn required the creation of emergency additional quantitative easing to solve the problem[16], but which incidentally helped bring down the government of Liz Truss. It was not Kwarteng’s budget but the Bank of England’s hasty implementation of quantitative tightening that actually created that crisis. The continuing sale of more than £80 billion of excess bonds a year as a result of quantitative tightening operations is what is contributing to the current record levels of bond sales in the UK, resulting in the risk of the market being over-stressed in a way that normal levels of sale would not do[17]. If, as is now necessary, Bank of England base rates are reduced dramatically to avoid the risk of deflation and recession then those bond sales could cease and as a result there would be no threat to market capacity to buy bonds inthe UK.

- There are serious problems with the structuring of the UK’s supposed national debt. In particular, it is extremely difficult for most people to acquire a part of this debt and yet it is apparent that most people would wish to save in government backed bank accounts if they could. The evidence of that is clear from the fact that an £85,000 deposit guarantee has to be supplied by the government to induce people to save elsewhere. They will only bank with commercial banks because the government has provided that guarantee. It is likely that if the government provided access through a state bank to a full range of deposit facilities, current account banking, and (maybe) limited credit facilities, the demand would be significant, and the amount placed on deposit with the government would rise dramatically and any stress on the so-called national debt would totally disappear.

- This would be particularly appropriate when there is an obvious need for increased state investment in the UK, which could only be funded by debt. Social housing, the NHS, education, flood defences, transport, energy transformation as a result ofclimate change, and much else demand funding and no business would pay for this out of revenue: they would borrow. So should the government. To attract the necessary funds for this investment. The government should:

-

- Change ISA rules so that existing ISA arrangements are suspended henceforth and all tax-free savings opportunities provided by the government are made available on the basis that the funds saved be used for the purposes of funding national infrastructure development. At present £70 billion of funds go into ISAs a year with an annual cost subsidy in terms of tax foregone of £5 billion.

- Change rules on pension tax relief, so that in consideration of that relief being granted, 25% of all new pension contributions should similarly be required to be invested in bonds, shares, or other structures that fund national infrastructure development, whether in the state or private sectors, subject to a strict taxonomy being in use. Nothing is more important to pensioners than having a future where they can draw down their pension.

- It is suggested that these two changes to pension to tax incentivised savings rules could raise £100 billion a year for the government by attracting new savings into government accounts to fund the transformation of the UK economy[18].

- The boost in economic activity that the investment funded in the fashion noted in the previous paragraph would be sufficient to fuel growth within the UK economy sufficient to more than fund the cost of any resulting interest charge payable by the government out of taxes raised. Fiscal multiplier effects arising from the investment made would deliver this outcome. This integration of fiscal and monetary policy is essential in the future.

- There should be a re-definition of the national debt. It should no longer be called the national debt, because that is not what it is. It should, instead, be called national savings, because that is what those parts owing to persons who save with the government actually are.

- Finally, those liabilities shown as owing on the Whole of Government Accounts[19] to commercial banks as a consequence of the creation of central bank reserve account balances by the Bank of England, on the instruction of the government, should now be properly described as national equity, because only the government has this right to create and inject money into the economy and without it doing so there would be no economy that could function. What is more, since that sum could only ever be repaid using money newly created by the government, which would be instantly re-deposited with it, these balances cannot be debt and must therefore be distinguished from anything approximating to that description elsewhere in the national accounts by calling them national equity.

I shall be happy to provide the Committee with further evidence in support of these suggestions if they wish for it and to appear in person before the Committee if that is the members’ wish.

Finally, for a fuller explanation of the national debt and issues arising from it, please seehttps://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/National-debt-an-explanation-published.pdf which explores the issues raised here in more but accessible depth.

8 February 2024

[1] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/623a22078fa8f540ecc60532/DMR_2022-23.pdf provides evidence that the previous mechanisms for manging cash requirements still exists. The government overdraft, or so-called Ways and Means account used for this purpose until 2008 was temporarily expanded to include a £20 billion facility in April 2020. Its previous use was faded out after 2008. See https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/10808/sa240108.pdf. Any suggestion that the current way of managing debt by always seeking to borrow to make good shortfalls is normal is, as a result, wrong: it is a recent innovation.

[2] Article 104(1) of the Maastricht Treaty, supported by Article 21.1 of the Protocol sought to limit use of such arrangements but can no longer apply if the UK chooses that it should not do so.

[3] ibid

[4] See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/glossary/Q/#quantitative-easing and https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/glossary/T/#the-qe-process for an explanation of the QE process, which is rarely properly understood.

[5] See most especially section 19 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/11/section/19

[6] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/freedom-of-information/2020/details-of-the-bank-of-england-loan-to-the-government-in-1694#:~:text=When%20the%20Bank%20of%20England,loan%20in%201694%20was%208%25.

[7] See https://www.ft.com/content/1ffa3bb6-ae87-3b6c-aa5c-7a48ca1fc2e2

[8] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/asset-purchase-facility/2023/2023-q3

[9] The Bank of England Asset Purchase Finance Facility Limited (APF)

[10] See the letter establishing the APF in which it was made clear that a) the Bank of England would act under direction from the Chancellor of the Exchequerand b) the Bank of England would be indemnified for any gains and losses that it made as a result of undertaking activity on behalf of HM Treasury and c) note the fact that as a consequence the accounts of the APF are not consolidated into those of the Bank of England because it isw not a subsidiary under its control.https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2009/chancellor-letter-290109

[11] https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/xl5bo4as/jul-sep-2023.pdf provides evidence of this.

[12] https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/whole-of-government-accounts

[13] See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2023/12/24/the-good-news-this-is-christmas-is-that-trillion-of-the-uks-national-debt-does-not-exist/ for further explanation.

[14] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/market-notices/2022/september/apf-gilt-sales-22-september

[15] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/sep/23/kwasi-kwarteng-mini-budget-key-points-at-a-glance

[16] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/2022/september/bank-of-england-announces-gilt-market-operation

[17] See https://www.ftadviser.com/investments/2023/09/08/is-now-a-good-time-to-buy-gilts/ for a discussion of this issue.

[18] See https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-QuEST-for-a-Green-New-Deal.pdf

[19] https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/whole-of-government-accounts