culture

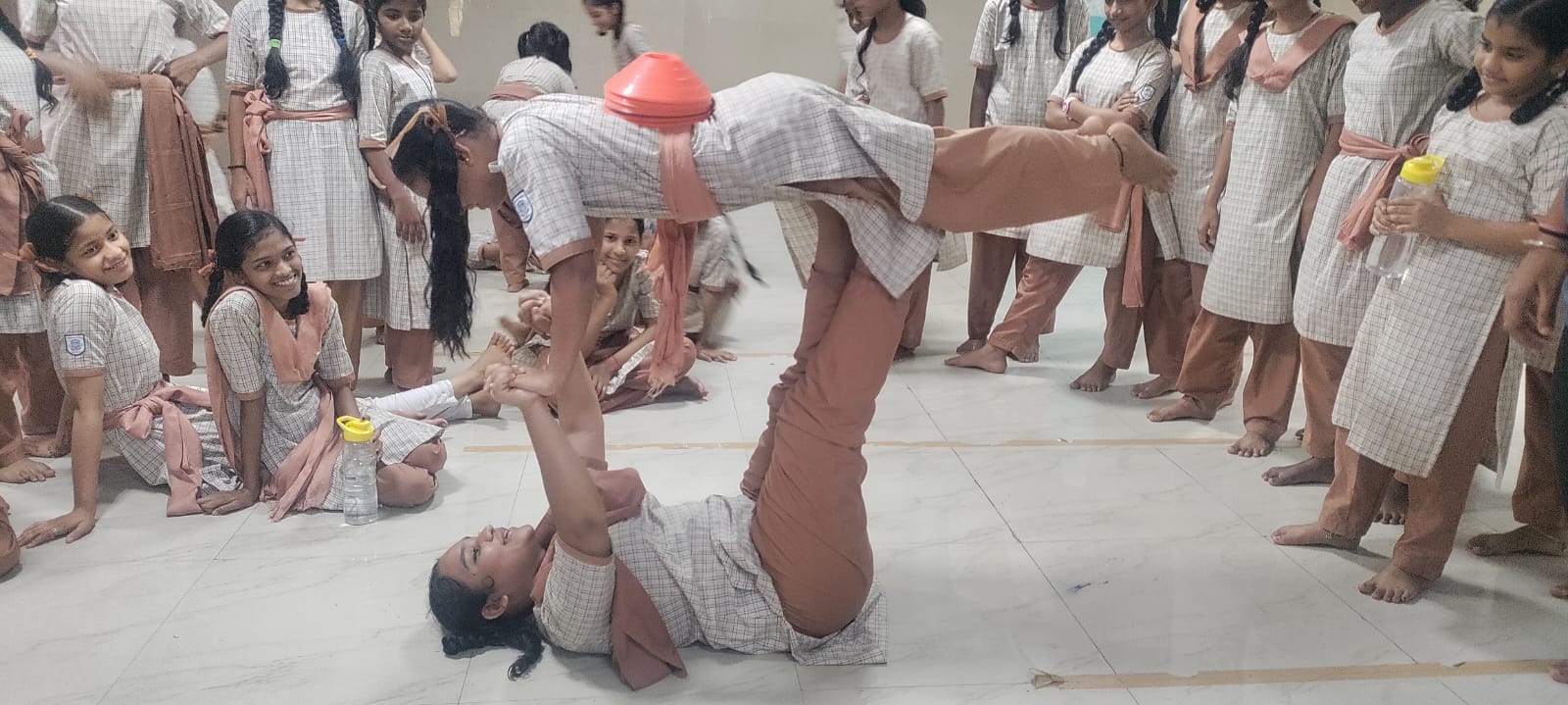

How Teen Girls in Mumbai Are Learning to Stand Tall

As Nausheen, a 14-year-old Mumbai schoolgirl, demonstrates the kicks and punches she has newly learned, there is a perceptible change in her body language. From a shy, giggly teenager, she turns into a budding supergirl: somehow she seems taller, her stance straighter and her voice louder.

“When I practice these moves, I feel a surge of power inside me,” she says. “I feel like I don’t have any fear.”

Nausheen has been learning martial arts — among other concepts such as consent and communication — at the free biweekly workshops conducted by the nonprofit MukkaMaar at her government school in a crowded Mumbai suburb. “I have learned to be strong and to face people with confidence,” she says, “whether it is my parents at home or strangers outside.”

MukkaMaar partners with 56 government schools in Mumbai. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

MukkaMaar partners with 56 government schools in Mumbai. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

Contrast this with what MukkaMaar’s founder Ishita Sharma remembers from a casual conversation with a group of middle-school girls a few years ago. When asked what they would do if someone attacked them on the streets, they unanimously responded: Shout bachao bachao! (help).

“They didn’t even think about it,” Sharma says. “It was a natural response to expect someone else to come and save them, because that is what they have been taught, what they have seen in movies.”

It was with the basic aim to shift this control from the outsider to the individual that Sharma started MukkaMaar — roughly translating to “throw a punch” — as an empowerment program for adolescent girls. “Women need to take responsibility for their own safety and not succumb to the ‘What will the poor woman do?’ narrative,” she explains.

Courtesy of MukkaMaar

At MukkaMaar’s free workshops, girls learn martial arts and build confidence. They also learn about communication and consent.

Sharma began in 2016 with four girls on a public beach and the conviction that teaching self-defense was the way to empower them. Over seven years and 3,000 girls later, she has learned that along with martial arts, there is also a need for a change in fundamental beliefs and attitudes. She shares examples of how these girls are schooled to be “good daughters” who grow up to be “good wives” (for instance, to blindly marry the man chosen by their parents, as opposed to committing to a “love marriage”). She explains that there is a need to teach them to question and debate at home, negotiate for their rights, develop and assert their own personalities, and so on.

MukkaMaar now partners with 56 government schools in Mumbai, where martial arts teachers are trained to listen to and counsel the girls, who open up with their own stories. These trainers are young men and women in their late teens and 20s, who usually work in teams of two. At 19, national level boxing champion Aradhana Gaund is not much older than the girls she trains. “They treat me like their friend, and I laugh and cry with them,” she says.

In the workshops, girls learn that violence is not a knee-jerk response, but a last resort. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

In the workshops, girls learn that violence is not a knee-jerk response, but a last resort. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

Elsa Marie D’Silva, founder of Red Dot Foundation, a nonprofit working to create safe spaces for women, says it can be intimidating for young women to stand up against harassment, and so “it is important to show them how they can speak out together, along with their friends or as a group, to call out bullies.” Indeed, this is one of the things that gives Gaund the most satisfaction: seeing how these classes have taught the girls to band together and support one another.

According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2023, India ranks a dismal 127 out of 146 countries, based on indices such as access to education, economic opportunities and health. What is even more concerning is the unceasing, systemic violence against women that takes several forms including intimate partner violence, rape and assault, dowry deaths, acid attacks and everyday street harassment.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Women are told from childhood to keep their heads down and take these things in stride, that to react would be futile and even dangerous. They internalize this to such an extent that they suffer harassment silently, which in turn encourages their abusers to carry on with impudence. This is where MukkaMaar has been making a small but significant difference.

Iqra, 13, says, “Earlier, I used to move away quietly when a man touched or groped me in the [public] bus. But now, I just make my voice loud and strong like I have been taught, and tell them to stop it.” At this, her friend Fatima chimes in, “Now we feel like we can also walk and talk like the boys.”

Courtesy of MukkaMaar

Ishita Sharma started MukkaMaar with the goal of changing girls’ “natural response to expect someone else to come and save them” — and showing them that they can be the ones in control.

But they have both also been taught that violence is not a knee-jerk response, but a last resort. “If we fight, we will also get hurt, but we can speak up,” Iqra declares with the wisdom of one far older.

And speak up they do, at every chance. “At my cousin’s wedding, a boy I don’t know started teasing me,” Fatima recalls. “When I shouted at him, his mother intervened and scolded him. Earlier I used to feel nervous in such situations, I used to think, ‘I am a small girl, what can I do?’”

As Sharma describes it, “We are not telling them that violence is the answer, but that violence should not be tolerated.”

“We train them to vocalize their feelings, to open up their shoulders and lift up their chins,” explains one of MukkaMaar’s trainers. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

“We train them to vocalize their feelings, to open up their shoulders and lift up their chins,” explains one of MukkaMaar’s trainers. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

The MukkaMaar website states, “It is necessary to recognize that violence includes microaggressions, discrimination, threats, and loss of opportunity as much as assault.” The training, therefore, does not just cover self-defense but also building physical fitness and emotional strength, as well as boosting (and often instilling) self-confidence.

Senior training fellow, Bhishma Mallah, 26, who has been with MukkaMaar for over four years, says that the girls begin with so many barriers, like shame and fear, that even to get them to exercise in front of others or to express themselves verbally is a challenge. “We train them to vocalize their feelings, to open up their shoulders and lift up their chins. We have to tell them repeatedly to forget about adjusting their dupatta [traditional scarf used to cover head or shoulders] and focus on the activity.”

Even during workshops, the girls ask for permission before making physical contact. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

Even during workshops, the girls ask for permission before making physical contact. Courtesy of MukkaMaar

One of the many ways in which the trainers chip away at the diffidence of these young girls is by making them chant “I am important” even as they practice their moves. Or asking them to imagine how a dog growls, and to channel that aggression in their kicks and punches.

Each hour-long session includes 20 minutes of conversations and counseling, with the remaining time devoted to physical training. “We teach them about concepts like boundaries, consent and safe touch. Even during lessons, they have to take permission from their partner before any physical contact,” explains Mallah.

Sharma admits it took her a couple of years to realize that for a girl to build agency, there is a lot of familial and social conditioning that needs to be undone. “There is no point in teaching them martial arts alone, with its focus on discipline and technique — because unless we teach them critical thinking, it is all pointless, and forgotten the minute they step out of the classroom,” says Sharma.

Red Dot Foundation founder D’Silva adds a word of caution: “It’s not enough to just empower the girls to speak up, it is also the responsibility of adults to listen to them when they do. If their parents or teachers don’t take them seriously, then the child will quickly learn not to tell anyone — because there is the added fear of having their personal freedom curtailed under the guise of protecting them or saving the family honor.”

A change in the larger ecosystem may take a long time, but it is clear that something is shifting within these girls. While one cohort confronted a cop making a video call in front of them and challenged him to prove he was not taking their photos without permission, another group of girls gathered the courage to file a police complaint against their physical education teacher who had been harassing them. For others, it has meant something as seemingly trivial as talking back to their fathers and challenging gendered rules and restrictions.

“I have learned to be strong and to face people with confidence,” one MukkaMaar student says, “whether it is my parents at home or strangers outside.” Courtesy of MukkaMaar

“I have learned to be strong and to face people with confidence,” one MukkaMaar student says, “whether it is my parents at home or strangers outside.” Courtesy of MukkaMaar

These may seem like small incidents, but for these young girls in Mumbai, the freedom to think independently and challenge those around them has been life-changing.

In the short run, Sharma says MukkaMaar wants to focus on fewer places and create retention, rather than spread the program thin all over the city. The future is digital for MukkaMaar alumni, with a chatbot that helps the girls have a two-way conversation about self-defense techniques, physical fitness, understanding of different types of gender violence and soft skills like communication and negotiation. This keeps them connected to the program, and to everything they learned in it, even after they leave.

The post How Teen Girls in Mumbai Are Learning to Stand Tall appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The Perks of Virtual Coworking With Strangers

From a young age, Alexis Haselberger’s son always asked someone to stick around when he needed to get chores or homework done. At first, she wondered why he needed help.

“Then I realized that he didn’t need me to engage with him, he just needed to know that my body was there,” says Haselberger, a time management and productivity coach in San Francisco.

Though they were not initially aware of it, Haselberger and her son were practicing “body doubling,” which involves having someone alongside to help you focus on a task. The term was first coined in the 1990s by a coach specializing in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Haselberger’s now-13-year-old son has not been diagnosed with ADHD, but he continues to find body doubling helpful. So does Haselberger, who does have ADHD. She asks her husband to be around while she completes certain tasks, and she organizes regular video calls with work peers to make progress on “important but not urgent” goals. They start by sharing objectives, then switch off cameras and focus for an hour.

Alexis Haselberger began practicing body doubling before she knew the term. Courtesy of Alexis Haselberger

Alexis Haselberger began practicing body doubling before she knew the term. Courtesy of Alexis Haselberger

Video calls like these are part of a growing trend: structured online sessions, in groups or in pairs, for anyone who wants to resist distractions and get things done.

In focus

The exact cause of ADHD, which affects an estimated five to eight percent of children globally and often continues into adulthood, is unknown. Among adults, it can create problems with time management, following instructions, and focusing or completing tasks. Although more commonly diagnosed in children, diagnoses are rising rapidly among adults in some countries, particularly among women.

Kirsty Baggs-Morgan, 50, who lives in Malta and runs a business supporting HR professionals, describes herself as “an absolute shocker” for delaying boring tasks until the last minute. For a while, she would ask her assistant to join her on a call when she needed to complete a task, “but we’d end up just chatting for the whole hour.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

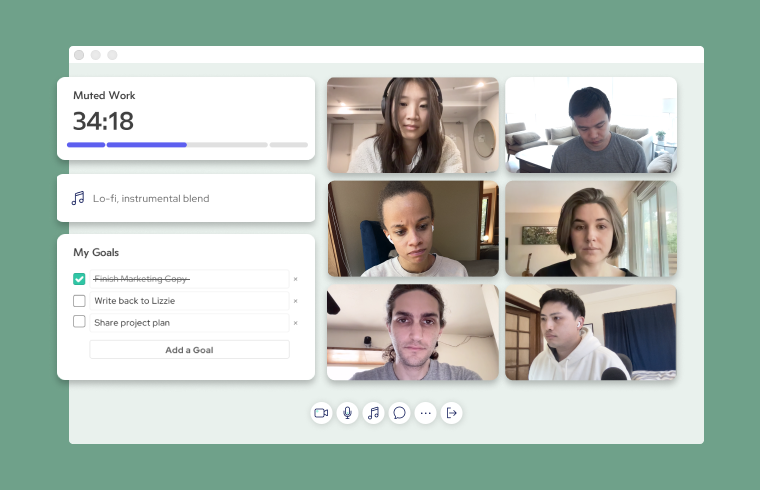

That changed with Baggs-Morgan’s ADHD diagnosis in August 2023. A coach recommended Flow Club, a company that hosts “virtual coworking sessions designed to drop you into productive flow.” As in Haselberger’s video calls, participants join a session and share their intentions, then get on with their work until the allotted time is up. In addition to multiple daily sessions, Flow Club users benefit from a supportive community — well over half of users are neurodivergent — and special features to aid focus, such as optional music and the choice of verbal or non-verbal sessions.

Already, Baggs-Morgan has racked up well over 130 Flow Club sessions — often while sitting in a physical coworking space. “For me it’s been an absolute game-changer,” she says. While the physical community provides real-life interaction, the online one helps her to get work done, and even to stick to a regular morning routine. “I like step-by-step instructions. I’ll actually do it because it’s written down,” she says, referring to the to-do list that every participant fills in at the start of a session. Other users might be doing anything from decluttering to writing a book — Baggs-Morgan even recalls someone using a session to take a nap.

Kirsty Baggs-Morgan often participates in online coworking sessions while also in a physical coworking space. Credit: Andreea Tufescu

Kirsty Baggs-Morgan often participates in online coworking sessions while also in a physical coworking space. Credit: Andreea Tufescu

Focusmate is similar to Flow Club, but puts users into pairs instead of groups. It was founded in 2016 by Taylor Jacobson, who had long fought procrastination himself. In 2011, he asked to work remotely — “and then I got fired from my job,” he explains, “because I just could not focus.” When he later got into coaching, he discovered the power of virtual coworking, and was convinced it could help millions of others like him.

Focusmate has now hosted over five million sessions, with users in over 150 countries. Like Flow Club, it was not designed with neurodivergence in mind (nor was Jacobson initially aware of the concept of body doubling), although more than a third of current users identify as neurodivergent and about 28 percent have an ADHD diagnosis. And while Focusmate is billed as being for “anyone who wants to get things done,” Jacobson suggests its value is much deeper, as he knows from experience: “When we say procrastination… you’re not living the life you want to live. ‘Procrastination’ sounds kind of trite, but it’s not. It’s really demoralizing and sad.”

Feedback from Focusmate users backs that up, Jacobson says: “It’s insane how life-changing this is for people.” A recent company survey among 212 regular users with ADHD found that their productivity increased by an average of 152 percent. Ninety-eight percent said Focusmate helped them make good use of their time, 82 percent that it helped them feel less lonely and isolated, and 88 percent that it improved their well-being. Flow Club does not have data specific to ADHD users, but co-founder Ricky Yean points to its “exuberant” testimonials and the fact that users attend an average of 10 to 11 sessions weekly.

CEO of the brain

Joining strangers online to get work done has become increasingly common, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic. Caveday and Flown offer virtual coworking for anyone; other services target particular audiences, like Writers’ Hour or Preacher’s Block. Online “study rooms” for students are also widespread.

Flow Club sessions include features to aid focus, such as optional music and goal lists. Credit: Flow Club

Flow Club sessions include features to aid focus, such as optional music and goal lists. Credit: Flow Club

But why do they work? Focusmate cites research on the benefit of “precommitment” and social pressure. Yean points out that even brief social interactions unleash dopamine, which drives motivation (dopamine levels can be lower among people with ADHD). Other research finds that we may change behavior when we know we’re being observed, that company can have a calming effect, and that our performance improves when we train alongside others.

For Haselberger, joining a body doubling session provides that small but important push to get started. “We know from the research that action begets motivation, and not the other way around,” she says. “If you are body doubling, then you’re saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this thing.’”

Zareen Ali, the London-based co-founder of Cogs, a mental well-being app for neurodiverse people, suggests body doubling is a way of outsourcing the “CEO of the brain” — the part that’s telling you what to do. “Having someone else take on that role acts as an external motivator,” says Ali.

Belonging matters

For neurodivergent people, there’s also the benefit of feeling less judged. Neurodivergent young people still face “a lot of bullying,” notes Ali, who studied educational neuroscience, and they often value peer support.

Kirsty Holden, 37, echoes the importance of finding like-minded people. She is awaiting an ADHD diagnosis, following years of feeling that something wasn’t right. “I grew up not really feeling a part of anything,” she says.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Holden, an online business manager based in Yorkshire, England, was not tempted by platforms like Focusmate or Flow Club, but joined the ADHD Business Collective, a coach-led program that includes body doubling sessions. She values the personal element: “Just knowing that those people get me and know my name… that’s what I really like.”

“For a lot of ADHD-ers, we haven’t felt safe to share what is going on in our minds,” Holden adds. But that is changing. “There are people out there that understand this, there are places where we belong.”

More scaffolding

Online body doubling is unlikely to work for everyone. Neurodiversity is “a massive, umbrella term,” Ali points out, and even people with the same diagnosis may be very different. She herself is autistic and finds body doubling distracting.

One of the barriers highlighted by both Focusmate and Flow Club is apprehension about meeting new people. Asking for a body double might also feel like admitting you need help, says Jacobson. Users of both platforms are majority women; Yean wonders if men find it harder to show some vulnerability.

Flow Club founders David Tran and Ricky Yean. Credit: Flow Club

Flow Club founders David Tran and Ricky Yean. Credit: Flow Club

Things have come a long way since the pandemic-prompted surge of remote working. Tools like Zoom expanded what was possible, but there was a lack of tech to properly support new ways of working, says Yean. People were “burning out like crazy” as they struggled with more responsibilities than ever and blurred boundaries between work and personal life.

“We went from ‘we can’t’ to ‘we can,’ but that’s such a low bar!” says Yean. “Are we thriving? Are we happy? … And are we able to manage all this?”

Flow Club — which aims to create a space of positivity and friendliness — is “in our little corner of the internet, which is trying to create a little bit more support, a little bit more scaffolding, a little bit more camaraderie with other people who share your mission or share your goals,” Yean continues. “I think we have learned that there’s ample opportunity to create more of these types of spaces that are much more supportive. And I think you can define ‘supportive’ in so many different ways.”

The post The Perks of Virtual Coworking With Strangers appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The New Age Fantasy of a Celtic Church that Revered Nature and the Divine Feminine Never Existed — So What?

From Fifth Avenue to Dorchester Heights, this St. Patrick’s Day will feature the traditional uilleann...

New Research Suggests That Belief in Demons May Help Explain Christian Support of Trump

In a strange way, I envy the people who were raised as evangelical Christians in...

Heartbreaking video as little Palestinian boy talks seeing of dad, pregnant mum executed

Shocking matter-of-fact retelling by Faisal Al-Khaldi spotlights the horror of everyday life under Israeli genocide

A video from Alaraby TV provides a devastating window on the horrific reality of life for Palestinians and their children under the genocide of their Israeli occupiers – but has also showcased the love, humanity and courage of the people of Gaza and the West Bank.

Ahmed al-Khaldi and his pregnant wife Fatima were executed in December when Israeli soldiers invaded their home, an incident confirmed by human rights group Euro-Med Monitor. Their son Adam was also killed and his four-year-old little brother Faisal was wounded but survived. Six others in the house were also murdered.

Little Faisal has now spoken to Alaraby about seeing his parents murdered:

As Alon Mizrahi, who shared the video to Twitter, pointed out, the video of Faisal shows a ‘premature maturity’ that can only be born out of great horror – but the love of the anonymous woman who is caring for him is just as powerful. Mizrahi, in a post accompanying the video, commented:

1. The maturity of this kid, which is way beyond his tender age. He recounts things he saw almost like an adult giving testimony. This kind of premature maturity is only the result of tragedy and disaster: a world in which children are not allowed to be children. This has been true for Gaza for generations, thanks to Israel’s occupation, siege and frequent wars.

2. The other thing that stood out for me was the amounts of love showered on this kid by the woman that we never see, but only hear her voice, see her hand and feel her presence. This really melts your heart immediately in it’s universal humanity, but it is also distinctly Arab. This kind of outpouring, heartfelt love, with this tone of voice, this pyisicallity [sic], that heart fully open – that is immediately recognizable to me as Arab.

This genocide has been started, and is being inflicted, with always the big political and cultural purpose of dehumanizing Arabs and Muslims: this has been its underlaying foundation. But what is happening is exactly the opposite.

Hundreds of millions of people have been exposed, for the first time in life, to the immense beauty, generosity, humanity, courage and wisdom the Muslim and Arab world are capable of.

This was made with the intention of making Muslims and Arabs hated, and presenting them as sub-human; but I think, for much of humanity, this has opened gated and portals of love that had been shut before. What is coming out from Gaza’s doctors and journalists and volunteers and rescue teams and children and just people – this has captivated the hearts of countless good souls around this planet.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

Phriscos

A “Frisco,” I recently learned, is “something that outsiders spontaneously say that secretly marks them as outsiders unbeknownst to them.”

[from a “The Far Side” comic by Gary Larson]

The concept, which came to my attention via Hanno Sauer (Utrecht), is related to the concept of a shibboleth, a linguistic term distinctive to a particular group, but kind of its opposite. Coined by Dan Engber, its name comes from the supposed fact that “people from all over the country think it’s cool to call San Francisco ‘Frisco,’ but no genuine native San Franciscans would ever use the word to describe their city.”

Several years ago we had a discussion of what we called “shibboleth names” in philosophy, that is, names the common mispronunciation of which marks speakers as inferior in some way. Maybe we should have called them “Frisco names.”

In any event, the domain of philosophical friscos—let’s just go all in and call them phriscos—goes beyond names and mispronunciations.

A classic example of a phrisco, offered by Scott Hill (Innsbruck) in response to Sauer, is using “begs the question” among philosophers to mean “raises the question” rather than “assumes the very thing it sets out to prove.” (Yes I know some of you think we should give up on this one, but nonetheless it still functions as phrisco.)

Here’s another phrisco: using “refuted” when one means “disagreed with”.

I think we could have a little fun, and at the same time provide a valuable service to philosophical novices, by identifying these phriscos.

The post Phriscos first appeared on Daily Nous.

A Farm of One’s Own

It was a day of joy and relief for Kamla: Her daughter was getting married—and the night before, it had rained. Far from a bad omen, the downpour had been ever welcome. Kamla is a farmer, whose livelihood is directly dependent on the land she cultivates, the land that gives her and her family a variety of vegetable crops to eat and to sell, like beetroots, tomatoes, beans, and chilis.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power – review

Caty Borum‘s The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power considers how comedy intersects with activism and drives social change. Borum’s accessible text draws from case studies and personal experience to demonstrate how comedy can successfully challenge norms, amplify marginalised voices and foster dialogue on issues from racism to climate change, writes Christine Sweeney.

Can you teach comedy? Can a sense of humour, charisma, delivery, stage presence and timing be learned? Comedy programmes popping up in universities across the world would say, “Yes, yes it can”. If the question is, “can you teach comedy as a tool for social change and civic power?”, Caty Borum has an entire book which aims to provide an answer.

Can you teach comedy? Can a sense of humour, charisma, delivery, stage presence and timing be learned? Comedy programmes popping up in universities across the world would say, “Yes, yes it can”. If the question is, “can you teach comedy as a tool for social change and civic power?”, Caty Borum has an entire book which aims to provide an answer.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power by Caty Borum explores the intersection of comedy and social activism, delving into the question of whether comedy can be taught and used as a tool for social change. Borum discusses the role of creativity, cultural power, and participatory media in driving social change and how postmillennial social-justice organisations collaborate with comedians. Serving as a follow-up to Borum’s work co-written with Lauren Feldman in 2020, A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice, this new book is a how-to manual with case studies on integrating comedy into social justice efforts.

[The] book is a how-to manual with case studies on integrating comedy into social justice efforts.

Borum reflects on her own comedy career, drawing from experiences working with sitcom legend Norman Lear on get-out-the-vote campaigns in the late ’90s and early 2000s like Declare Yourself. While these campaigns engaged young people and demonstrated the power of comedic efforts, Borum notes that the impact on electoral outcomes was limited. Though 2004 saw the largest turnout (nearly 50 per cent) of voters aged between 18 and 24, that demographic still accounted for just 17 per cent of the total voter population, and Bush beat his democratic rival John Kerry to secure a second term.

Although mobilising the public through comedy for direct political action may be too great an ask, Borum emphasises comedy’s narrative power in shaping public understanding and influencing cultural attitudes. The book explores the evolution of comedy in the participatory media age, especially its increased visibility during the pandemic and its role in challenging societal norms. The rise of independently produced content on social media has challenged the authority of networks and studios, boosting the democratisation and creative agency of comedy “content”. Though Borum acknowledges the benefits of social media for amplifying marginalised creators, she falls short of critically examining its impact on mental health, the spread of misinformation and biased algorithms. Despite this, she underscores comedy’s potential as a cultural intervention empowered by the participatory networked media age.

Positive deviance, according to Borum, is the quiet power of comedy that journalism lacks.

The book discusses the comedic response to political events, particularly the rise of Donald Trump, positioning comedy as a force for social change by offering fresh ways of undermining the status quo. According to Borum, comedians say what journalists cannot, thinking of Michelle Wolf, who at the 2018 White House Correspondents dinner pointed out the mutually beneficial cycle of journalists covering then-President Trump’s near-constant news feed. Positive deviance, according to Borum, is the quiet power of comedy that journalism lacks.

Comedy also serves as a creative space for marginalised voices, providing an alternative narrative and critique that traditional journalism may lack. Borum highlights the importance of optimism in comedy. Comedy provides a space for an alternate reality, for example the TV series Schitt’s Creek portrays a world where the LGBTQ community is fully accepted. In this sense, optimism can be a survival tactic. As Borum suggests,

[C]omedy as a force for social justice breaks down social barriers and opens space to discuss taboo topics; persuades because it is entertaining and makes us feel activating emotions of hope and optimism; serves as a mechanism for traditionally marginalized people to assert and celebrate cultural citizenship through media representation; acts as both social critique and civic imagination to envision a better world; and builds resilience to help power continued struggle against oppression.

Borum provides an in-depth, well-researched review of cultural entertainment activists, tracking the power of the entertainment industry to affect how people feel. “Pioneering cultural entertainment activists pushed for ‘mainstreaming’ oppressed people – including and normalizing their lives and lived experiences in entertainment.”

The book is something of a documented workshop, drawing from the experiences and insights of leaders across social justice activism and comedy to emphasise the power of media.

The book is something of a documented workshop, drawing from the experiences and insights of leaders across social justice activism and comedy to emphasise the power of media. Its instructive aspect lies in Borum’s description of running comedy workshops and writers’ rooms, offering a practical guide for both comedians and social activists. These collaborative spaces aim to translate key messages into comedy routines through storytelling, making complex issues more accessible. The author uses climate change and the opioid epidemic as examples, demonstrating how comedy can humanise and mobilise audiences to address pressing challenges.

Borum examines a case study of youth political activist group Hip Hop Caucus which aims to communicate a basic awareness of climate change to Black, Indigenous, and other People of Colour, who are the most affected by, and yet contribute the least to, climate change in the US (and globally). Even if this comedy work may not reach the oil companies responsible for the brunt of climate change, it serves to educate and mobilise audiences. In this sense, the messaging of the book goes, culture is important because it is the mechanism by which we relate to each other. Although it’s hard to demonstrate the material impact of comedy and the entertainment industry overall on political dynamics, communicating the mechanisms translating individual experiences in collective narrative storytelling to foster understanding and support is convincing.

Culture is important because it is the mechanism by which we relate to each other.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious emphasises the power of comedy as a force for social justice and provides practical insights into its integration with activism. She effectively shows how collaboration between the two has the power to start meaningful conversations around racism, climate change, economic disenfranchisement, addiction and more. Borum’s work serves as a valuable guide for media and communication theorists, entertainment industry professionals, social activists, and comedians, showcasing the potential of collaboration between comedy and activism in sparking meaningful conversations on various societal issues.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: Paul Craft on Shutterstock.

Contesting Moralities: Roma Identities, State and Kinship – review

In Contesting Moralities: Roma Identities, State and Kinship, Iliana Sarafian challenges established scholarly practices that attempt to define Romani identity, instead exploring how individuals navigate societal constraints with agency and resilience. Deftly combining ethnographic research, anthropological theory and personal reflection, this is an essential read for understanding the complexities of lived Roma experience, writes Martin Fotta.

The past decade has seen the publication of several high-quality monographs in various languages focusing on the lives, histories, and experiences of Romani people. While several have provided new insights into social processes, deconstructed existing preconceptions, or both, rarely has a book so subtly yet vehemently demanded that readers rethink their habits of thought about classical topics in Romani-related scholarship. This relatively short book by Iliana Sarafian, a talented anthropologist of Romani descent, does precisely this; it asks scholars to stop ruminating on who the Roma are and the character of ethnic boundaries, instead urging them to focus on how Romani individuals thrive within constraints and how they attempt to create spaces of survival for themselves and their families. It calls for exploring “experiences from the margins of Roma-ness” (98), but without presupposing to know what the core of Romani culture is.

The past decade has seen the publication of several high-quality monographs in various languages focusing on the lives, histories, and experiences of Romani people. While several have provided new insights into social processes, deconstructed existing preconceptions, or both, rarely has a book so subtly yet vehemently demanded that readers rethink their habits of thought about classical topics in Romani-related scholarship. This relatively short book by Iliana Sarafian, a talented anthropologist of Romani descent, does precisely this; it asks scholars to stop ruminating on who the Roma are and the character of ethnic boundaries, instead urging them to focus on how Romani individuals thrive within constraints and how they attempt to create spaces of survival for themselves and their families. It calls for exploring “experiences from the margins of Roma-ness” (98), but without presupposing to know what the core of Romani culture is.

Experimental in style and voice, Contesting Moralities is located within the ongoing effort to decolonise academic knowledge. The book is unique, however, in how the push to redefine the terms of representation in academic discourse is combined with solid ethnographic grounding and a commitment to anthropological theorisation. Weaving in self-reflection and personal narratives, it sheds light on broader social processes – on how racism, historical legacies, cultural traditions and social dynamics intersect in the lives of Romani individuals. It foregrounds individuals’ agency and the multifaceted nature of Romani experiences.

Weaving in self-reflection and personal narratives, [the book] sheds light on broader social processes – on how racism, historical legacies, cultural traditions and social dynamics intersect in the lives of Romani individuals.

The book is based on research in two pseudonymous Bulgarian Romani neighbourhoods – Radost and Sastipe – as well as in various state and non-state institutions. Sarafian is open about how practical circumstances and her position as a Romani woman influenced her research. For instance, she was assigned the role of a daughter when she first settled among non-kin and shut out from conversations of sexuality and intimacy among married women, as ignorance on such matters is expected from unmarried young Romani women. She does not treat these moments as constraints, however, but uses them as an opportunity to ponder social processes and patterning.

Sarafian is open about how practical circumstances and her position as a Romani woman influenced her research.

The main theme running throughout the book examines how Romani subjectivities are moulded by the state and its policies as they interact with values, practices, and relationships of kinship. The book focuses on a set of selected sites where the state has tried to interfere with Romani kinship, some of which are highly politicised and visible in everyday discourse: assimilation policies, control over fertility, disciplining of motherhood, and education of children. The book documents the scope of the state’s intervention and its violence past and present. “[T]here was no child in her Roma neighbourhood not going to some form of pansion [orphanage or a boarding school],” one of her research participants observes about life under the state socialism (85). The book charts the clash of state and kinship moralities and the contradictions this generates “inside” kinship relationships. It also documents various ways through which kinship resists the state or assimilates its initiatives.

Kinship, however, is not treated as a cultural artefact or tradition. Rather, the point that Sarafian tries to convey is that Romani kinship is oriented toward the future: weddings serve as communal projections of the potential for a better future, and childbearing reproduces this projection in the form of children. The concomitant aspect of this focus on becoming is Sarafian’s careful tracing of personal agency and capacity to aspire, even in moments where these could be the least expected, such as early marriages. At times, this struggle for self-determination is shown to be self-defeating. Such is the case of children, who take it upon themselves to protect their siblings and families from discrimination and racism, but in the process become further alienated from the educational system.

Romani kinship is oriented toward the future: weddings serve as communal projections of the potential for a better future, and childbearing reproduces this projection in the form of children.

The book is also a meditation on how, for people like Sarafian – who, in a move reproductive of antigypsyism, are sometimes dismissed as “Roma elite” – involvement in scholarship or activism becomes a mode to pursue authenticity and reflects their concern with the survival of Romani people. This dynamic generates its own contradictions, however. It threatens to co-opt Romani activists and scholars into co-constructing a figure of vulnerable and impoverished “hyper-real” Roma that would be legible to the state or development agencies. For many, in the context of racism and exclusion, these might be the only viable alternatives to achieve self-realisation while simultaneously connecting to their communities and responding to expectations from their families; for Sarafian, the book also becomes a way to connect with her family and community and to comprehend their position in contemporary Bulgaria. In a surprising twist, after she had been denied a job as a nurse at a local hospital, moved to work for an NGO, and then shifted to academia, Sarafian came to see a structural continuity between Romani activists, herself, and a woman who managed to become a doctor, but ruptured all relationships with her kin in the process: “I wanted to visit Ekaterina in Sofia to share that she was not alone, that there were other Roma who had managed to navigate the world within and outside of the Radost neighbourhood” (79).

The book’s style replicates its focus on the unfinished and ambiguous nature of social forms and processes, as well as the open-endedness of people’s aspirations. Rather than following one case study throughout the book or even through a chapter, each chapter is organised around a series of ethnographic stories and viewpoints. Some readers might find such a narrative approach difficult and desire some kind of synthesis or resolution. However, this is a deliberate writing strategy: “[W]hat there is still to say goes beyond the limits of this book” (101). The juxtaposition of fragments propels Sarafian’s description, sharpens her analysis, and invites future interpretations. Through ethnography, by highlighting particularities of various identifications or adding caveats to descriptions of kinship and state moralities, she constantly tries to re-articulate those social aspects that make a difference, often in ways she had not anticipated: “I found spaces, stories and examples of the everyday that challenged my preconceptions about Roma identifications” (11).

The chapter on education […] makes visible how any state effect is produced: in day-to-day interactions, in the intermeshing between institutional actions and everyday racialisation

My main objection to the book is that the state often comes across as a monolith. The only exception is the chapter on education, which makes visible how any state effect is produced: in day-to-day interactions, in the intermeshing between institutional actions and everyday racialisation, and in how teachers, directors, and schools translate policies, respond to economic constraints, and in turn shape the educational outcomes, and thus the futures, of Romani children – for better or worse. The book would have been much richer if such an approach had been reproduced in other chapters.

Sarafian is unapologetic and does not try to hide her motivations: “I wrote as I did because of the idiosyncrasies that have shaped me” (98). The result is a timely, readable book and an essential example of Romani autoethnography. Unlike Black autoethnographic writing, this genre remains underdeveloped in Romani-related scholarship, even in its critical iteration aimed at amplifying marginalised voices and empowering communities through challenging established forms of knowledge production. Contesting Moralities will therefore be of interest to those keen on understanding the complexities of being Romani in different contexts and to anyone interested in critical commentary on pressing social issues.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: Brum on Shutterstock.

Horror and Humor in Hulu’s The Other Black Girl

Based on the bestselling novel by Zakiya Dalila Harris, The Other Black Girl dissects the horror of insidious racism in white workplaces...