anthropology

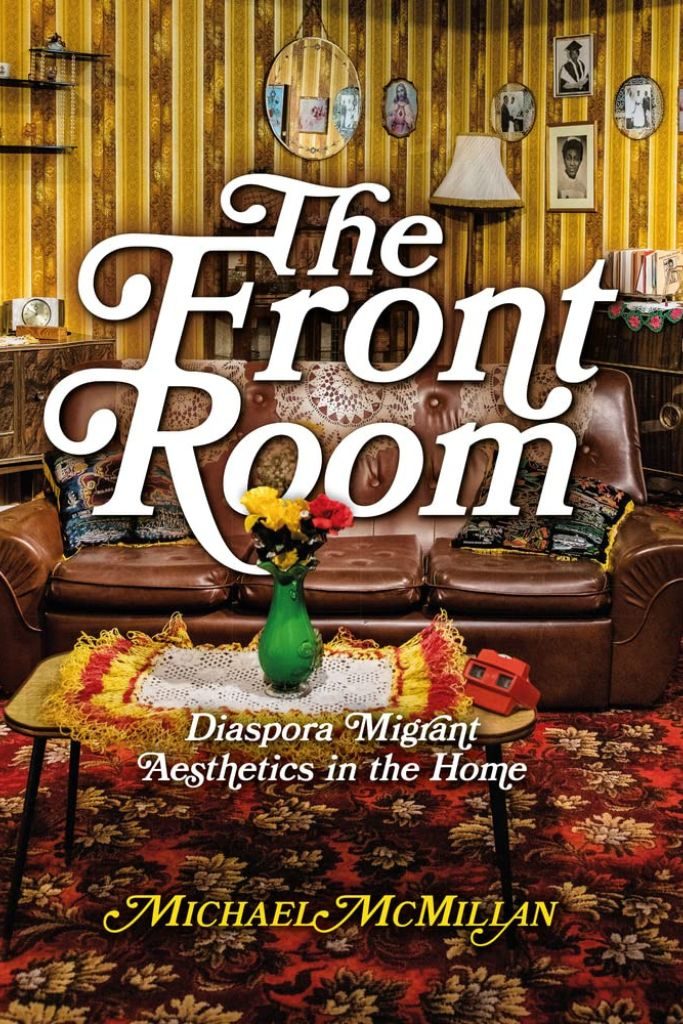

The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home – review

In The Front Room, Michael McMillan examines the significance of domestic spaces in creating a sense of belonging for Caribbean migrants in the UK. Delving into themes of resistance and creolisation, these sensitively curated essays and images reveal how ordinary objects shape diasporic identities, writes Antara Chakrabarty.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Migration, at its most basic level, means a physical relocation. However, this “mobility” entails a complex, polysemous reality whose consequences reverberate for those who leave one place for another. Michael McMillan’s The Front Room: Diaspora Migrant Aesthetics in the Home presents a poignant personal tale of materiality, memory and diasporic emotions. It connects with readers by presenting the past without falling prey to anachronism, narrating ordinary aspects of our day-to-day lives through pertinent sociological themes and recurring issues like racism, world politics, aspirations, diasporic memory and more. Michael McMillan, a playwright and artist, offers a text that unfolds as a choreopoem to the domestic spaces inhabited by migrants, infused with theatricality and a curatorial sensibility around the images and references shared. The book, originally published in 2009, has been re-released and is divided across several themes and including additional essays, including by eminent cultural anthropologist Stuart Hall.

Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves.

The book takes us on a journey of discovery as to what spaces meant, looked, smelled and felt like for Caribbean diaspora settled in the UK from the mid-20th century. It describes how the tactile sensations and emotions held in a room amount to so much more than its aesthetics. The text begins with a section on how Caribbean diaspora re-imagined the Victorian parlour, (the front room) through a sense of decolonial resistance, cultural survival and aspirational attempts to adapt to the new culture in which they found themselves. The images used to showcase the different varieties of such front rooms were mostly taken from the response to the exhibition, A front room in 1976 , curated by McMillan at the Museum of the Home in London in 2005-06.

A primary thematic focus is the emergence of a significant cultural process of change often called as creolisation which gives rise to a third culture which is neither Caribbean, nor British, but a diasporic intermingling of the two. This creolisation also occurs as a result of intergenerational change in the wake of World War Two and apartheid. Moreover, it speaks to the changing imagination around what can be called a “home”, reflecting changes in identity in a foreign land. The lucidity of the essays and the various references to sociological and anthropological works on the perception of “self”, vis-à-vis place making like those by Erving Goffman, Emile Durkheim, Stuart Hall gears the book towards students beyond the disciplinary boundaries of Sociology, Anthropology, Arts and Aesthetics, History, Museology and more. Towards the latter part of the book, McMillan also brings in other diasporic communities beyond the Caribbean, such as Moroccan, Surinamese, Antillean and Indonesian migrant communities in the Netherlands.

Front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community.

The book presents an important diasporic narrative underpinned by a critical struggle of the diasporic experience: underneath the subject of the ”front room” lies the process of subverted diasporic emotions and anti-assimilation cultural change. The emotional attachments are prioritised over fitting exactly within the typical British space. McMillan presents his readers with ten commodities that were normally seen in the Caribbean households which were also seen in the diasporic “front room” in the UK. These objects wordlessly communicated the Caribbean way of life without. A homogenisation of the objects found in the across the British Caribbean front room happened gradually as people visited one another, trying to emulate the aesthetics of a diasporic migrant culture. As someone from South Asia, I can vouch fora very similar pattern post-colonisation. Some chose to keep religious symbolic items at the forefront whereas the others chose to fit into the moral definition of aesthetics according to the British. A front room could become a Durkheimian quasi-sacred space which had to be seen beyond its mundane nature. McMillan emphasises the changes across generations and how front rooms generally resisted change, carrying forward an aesthetic and sensibility as the badge or identifier of a community. The book makes its readers aware of the significance contained in the spaces not just through imagery, but also literary compositions like songs, poems, and other varieties of literature.

The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes.

The book describes the affective power of objects through ten examples including the paraffin heater, which gave a sense of reassurance and reminded migrants of their homes through the scent of paraffin oil. The radiogram (a piece of furniture that combined a radio and record player) played the role of “home” in another new land, a sonic gateway into the past. Several other items also acted in service of what Goffman would call ‘impression management’ to a larger audience. The gendered division of aesthetics was apparent in the crochets made by the women in contrast to the glass cabinets and drinks trolleys that showcased men’s tastes. Notably, the carpets and wallpapers, though quintessentially British in theory, could be reclaimed and subverted through the choice of colourful options rather than plain base colours. The book also captures the effects of technological evolution through the inclusion of televisions, telephones and pictures of revered role models such as politicians and singers on display.

McMillan’s work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

One may make the mistake of perceiving this text as an over-romanticisation of material objects that convey diasporic identity. However, McMillan avoids this, convincing his readers of the deeply felt significance of the ordinary in connecting diaspora to the places they left behind. He bolsters this through setting ordinary items, spaces and lives in the context of unique epistemological nuances such as apartheid, cultural hybridisation, symbolic capital, taste and more. His work takes account of the constant search for refuge in the perfectly arranged room as a way of way of asserting one’s identity and materialising an authentic diasporic identity in one’s home.

The book is successful in its theatrical and thoughtful presentation and the depth it achieves over only a limited number of essays. Its effect is to fill readers’ minds with questions and to pave the way for similar studies in other postcolonial diasporic communities.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: 12matamoros on Pixabay

One Planet, Many Worlds: The Climate Parallax – review

In One Planet, Many Worlds: The Climate Parallax, Dipesh Chakrabarty examines human interrelatedness with, and responsibility within, the Earth System from a decolonial perspective. Drawing on a diverse range of disciplines, this book is a critical intervention that considers perspectival gaps and differences around the climate crisis, writes Elisabeth Wennerström.

One Planet, Many Worlds: The Climate Parallax. Dipesh Chakrabarty. Brandeis University Press. 2023.

In One Planet, Many Worlds, Dipesh Chakrabarty addresses existing perspectival gaps and differences around the Earth System. This latter term can be understood from the International Biosphere-Geosphere Programme’s definition (7) as a system integrated with the planet’s physical, chemical, and biological processes, of which humans are a part. Chakrabarty makes the “globe/planet distinction” (3) to navigate the climate crisis alongside the Earth System. The parallax is a helpful yet critical concept highlighting how appearances change depending on where the focal point rests.

In One Planet, Many Worlds, Dipesh Chakrabarty addresses existing perspectival gaps and differences around the Earth System. This latter term can be understood from the International Biosphere-Geosphere Programme’s definition (7) as a system integrated with the planet’s physical, chemical, and biological processes, of which humans are a part. Chakrabarty makes the “globe/planet distinction” (3) to navigate the climate crisis alongside the Earth System. The parallax is a helpful yet critical concept highlighting how appearances change depending on where the focal point rests.

Climate awareness is not a new concern, and the distribution of adverse climate impacts is highly unequal

The case in point: climate awareness is not a new concern, and the distribution of adverse climate impacts is highly unequal. Chakrabarty asserts that failures to act in relation to the Earth System are evidenced not only by the climate crisis but also in energy extraction politics (eg, 9 and19) and global justice debates (eg, 43 and 79). In contrast, he cites Kant’s emphasis on the “categorical imperative” to follow moral laws, regardless of their desires or extenuating circumstances. Arendt is further emphasised in the case for collective action. But in the Anthropocene, argues Chakrabarty (invoking Kant and Arendt on ethics), there are many signs of how the approach to addressing the climate crisis risks being “bereft of any sense of morality” (6).

Chakrabarty’s research interests intersect with themes in modern South Asian history and historiography, globalisation, climate change, and human history

As a leading scholar of postcolonial theory, comparative studies and the politics of modernity, Chakrabarty’s research interests intersect with themes in modern South Asian history and historiography, globalisation, climate change, and human history. This book demonstrates his extensive commitment to communicating change through a socio-historical narrative. The text is multidisciplinary in scope, moving freely between the natural and social sciences and the humanities. The critical premise is the need to learn from what may appear complex and from what is multifaceted.

He deconstructs “global warming” and “globalisation” by differentiating their relationship to the Earth System (eg, 19-21 and 56). Chakrabarty argues that the Earth System can be delimited as “a heuristic construct” when used in Earth System Science (ESS), wherein scholars’ focus on monitoring geological and biological factors (3). Chakrabarty finds a more fruitful discussion from a continued historicisation of “global histories” and the “geobiological history of the planet” in the different meanings of the “globe” – including “the 500-year-old entity brought into being by humans and their technologies of transport and communication…a human-told story with humans at its center” (3). The discussion includes the COVID-19 pandemic (Chapter One), postcolonial historiographies around an “Earth system” (Chapter Two), and the need to reconcile what Chakrabarty refers to “as ‘the One and the Many’ problem that makes climate change such a difficult issue to tackle” (15) (Chapter Three).

The climate crisis is entangled with political factors, economic growth processes and capitalism, in part seen in the reverberating effects of natural resource extraction

Chakrabarty contends that the climate crisis is entangled with political factors, economic growth processes and capitalism, in part seen in the reverberating effects of natural resource extraction – what many scholars refer to as the Great Acceleration. Complementary notes expand such negotiations to Derrida’s “democracy to come” (60) and Hartog’s discussion on the elements of time and space that pose a particular political problem in the Anthropocene (22, 69, 74). Here, perspectives differ not only over whether Anthropocenic humans lie at the centre, but around the Earth System, which is one while also entailing many differentiated and interrelated processes (7-8). He states: “Any human sense of planetary emergency will have to negotiate the histories of those conflicted and entangled multiplicities” (16).

Many injustices and inequalities in the Anthropocene are repressed, too; he gives the example of how many longed for the pandemic to be over and for life to return to normal, yet when it came to vaccinations, this desire turned political (22). The pandemic shows, according to Chakrabarty, how we are “entwined with the geological – over human scales of time and space” (73).

He references Foucault’s biopolitics where “natural history remains, ultimately, separate from human history” (31), and more of a critique on modern political thought: “We are a minority form of life that has behaved over the last hundred or so years as though the planet was created so that only humans would thrive” (39). In contrast, the biologist Margulis combined three Greek words (hólos for “whole,” bíos for “life,” and óntos for “being”), in the understanding of the holobiont, the superorganism that hosts a myriad of other life, of which humans are a part (38).

Chakrabarty offers no essential framework to address the climate crisis. Still, he contends that the critical question remains how to navigate the present and respond alongside the Earth System.

Chakrabarty offers no essential framework to address the climate crisis. Still, he contends that the critical question remains how to navigate the present and respond alongside the Earth System. He suggests that multiple entry points for the reconfiguration of hegemonic “contemporaneity,” can be found in the writings of thinkers across disciplines – from philosophers, physicists and botanists to activists, marine biologists and anthropologists, including Hartog (69), Latour (71), Todd (95), Winter (96), Haraway (98), and Kimmerer (103). By deconstructing “the globe” he reimagines the contours of connective global histories, citing the impetus of “Haraway and Indigenous philosophers—to make kin, intellectually and across historical difference” (102). Charabarty’s text draws together all these ideas to unpack the asymmetrical patterns of time and space in the Earth System and make a case for global environmental justice. Overall, Chakrabarty’s work One Planet. Many Worlds makes a critical intervention on how to think about the climate crisis, deconstructing the present way of being within the Anthropocene.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Triff on Shutterstock.

Love and Technology: An Ethnography of Dating App Users in Berlin – review

Fabian Broeker‘s Love and Technology: An Ethnography of Dating App Users in Berlin explores how dating apps mediate intimacy among young Berliners. Presenting an immersive ethnography of app usage, users’ experiences and perceptions and Berlin’s particular dating culture, Jiangyi Hong finds the book a rich work of contemporary digital anthropology.

Love and Technology: An Ethnography of Dating App Users in Berlin. Fabian Broeker. Routledge. 2023.

With the advent of digital communications technology, dating apps have provided new avenues for finding and nurturing romantic relationships, while also raising many critical questions for social scientists. A recent concern in digital anthropology is that of social relationships and interaction patterns. Intimacy, which people desire in their primary relationships, is now often mediated by dating apps that intervene in one’s lived experience. Fabian Broeker’s Love and Technology: An Ethnography of Dating App Users in Berlin is an immersive ethnography exploring the mediation of intimacy in personal relationships in Berlin.

With the advent of digital communications technology, dating apps have provided new avenues for finding and nurturing romantic relationships, while also raising many critical questions for social scientists. A recent concern in digital anthropology is that of social relationships and interaction patterns. Intimacy, which people desire in their primary relationships, is now often mediated by dating apps that intervene in one’s lived experience. Fabian Broeker’s Love and Technology: An Ethnography of Dating App Users in Berlin is an immersive ethnography exploring the mediation of intimacy in personal relationships in Berlin.

Through a combination of digital ethnography and narrative methods, Broeker provides an in-depth exploration of the romantic lives of young, Berlin-based dating app users. The ethnographic research entailed online and offline participant observation of how young people in Berlin use dating apps and how the apps shape the experiences, behaviours and perceptions of individuals seeking romantic relationships, sexual experiences and love.

Broeker is primarily concerned with Tinder, Bumble, and OkCupid, the three most popular apps encountered in the fieldwork, and describes different dating experiences, finding that young people in Berlin often use more than one app. Throughout this study, Broeker mentions the notion of “affordances” (1), which occur when particular actions and social practices are made easier or preferable due to “a specific cultural context and setting” (2). Broeker foregrounds the affordances dating apps allow without neglecting the fluid relationship between the user, social and material environment, and technological artefacts.

‘Each app on a phone act[s] as a certain canvas of projection’ (25) that shapes and is interpreted based on young dating users’ own experiences, social circles, and cultural values.

In his fieldwork, Broeker explored what each dating app means to participants, the experiences each app could enable, and the coded notion of intimacy in each app (eg, Tinder is associated with primarily brief sexual encounters). Broeker unfolds the complex relationship between users and dating apps, paying particular attention to how “each app on a phone act[s] as a certain canvas of projection” (25) that shapes and is interpreted based on young dating users’ own experiences, social circles, and cultural values. Positioning dating app users alongside this understanding of intimacy, Broeker astutely observes that for these users, switching between different dating apps is not only about browsing their availability to chat with potential partners but also “symbolises about their own identity and the community their membership would align them with” (37).

As Broeker discusses, in the context of this affordance environment, it is worth considering how other forms of mediated communication affect the dating rituals of Berlin’s dating app users. Therefore, he acknowledges in the field survey the importance “within dating rituals of moving from dating apps to other communication services within the framework of users’ mobile devices and the particular social and technological implications of such transitions” (50). Using the term “ritual”, Broeker tends to view dating as an activity that entails multiple actions within underlying meanings and emphases, some being pivotal moments in the development of the relationship and intimacy. Broeker’s work continues along that trajectory, showing not only how the recognition of the courtship rituals inherent in the dating app affects young people in Berlin, but also the significance of traditionally gendered heterosexual dating rituals, (eg, men taking the initiative in dating).

One area where Broeker succeeds is his nuanced discussion of awareness of social manipulation of space (eg, date locations) and personal understandings of intimacy among dating app users in Berlin.

As Broeker contends, the city space is an important arena in which people use dating apps. That space is formed of social relations and carries a plethora of nuanced social cues and rituals. Broeker spent a lot of his time going to different participants’ workplaces or residences and completed interviews with participants in different streets and neighbourhoods. One area where Broeker succeeds is his nuanced discussion of awareness of social manipulation of space (eg, date locations) and personal understandings of intimacy among dating app users in Berlin. This is significant because previous studies about users’ dating experiences often overlooked multiple interpretations of how people move in and choose to occupy cities. This book speaks directly to that aspect – for example, the perception of a user’s choice for a date location will affect people’s first dating impression; different places integrated into the self-presentation of impression management when people design their profiles; and the choice of the location of the first meeting is regarded as reflecting their personality. Therefore, as Broeker explains, city space is positioned as a stamp of dating users’ identity. How to interpret identity and project their values and desires into city space has become a key moment for users to consider on dating apps.

The dating culture of Berlin is included in the idea of an ‘anything is possible’ city hosting limitless hedonistic possibilities.

Berlin is not only a series of spaces but also an area for dating app users to explore and navigate, and it “is built upon a collective imagination” (133). Broeker interprets participants’ conversations and personal descriptions of the dating experience to show that the city is “a particularly free, inclusive and open metropolis”, giving Berlin “the reputation of a particularly free hedonistic paradise” (133). Therefore, the dating culture of Berlin is included in the idea of an “anything is possible” city hosting limitless hedonistic possibilities.

Another important contribution Broeker makes is his analysis of Berlin’s particular dating culture, with a broader understanding of the intimate relationships that the city’s youth form through dating apps. Broeker discusses Berlin’s unique dating culture through two practices, “stories” (119) and “screenshots” (123). Stories are a form of social currency in people’s social activities, traded in conversation. People share their dating experiences by talking with others and trying to narrate unique dating stories, a common topic in their social circles. Broeker suggests that some people even want to have bad experiences to attract others.

Broeker argues that while the app expands the interaction of potential partners, the use of apps limits the narrative of intimate relationships, making encounters less romantic and special.

Screenshots also play a role in dating experiences. Broeker points out that sharing screenshots is not only a central means by which dating users in Berlin communicate their dating experiences, but also a tool for Berlin young people to “see” dates through visual or textual images on communication platforms. This exploration of storytelling and screenshots circles back to a discussion of dating culture in Berlin. Broeker notes that although the dating app provides a tangible nucleus for users around which dating stories can be constructed and explored, respondents still focused on the idea of nostalgic romantic narratives. Thus, he argues that while the app expands the interaction of potential partners, the use of apps limits the narrative of intimate relationships, making encounters less romantic and special.

While the book’s in-depth presentation and excellent analysis of ethnographic details and theory are impressive, some readers may find its academic nature and use of technical terms difficult. Broeker’s assumption of some knowledge of academic discourse (such as the assumed knowledge of rituals of intimacy and academic definition of polymedia) may be off-putting and inaccessible for the general reader. Overall, Love and Technology is an intelligent and perceptive contribution to the field of digital anthropology. Readers can gain important insights into the intricate interplay between technology, culture and intimacy from Broeker’s work. This book will inspire and provoke thought, regardless of whether you are a scholar interested in modern intimacy and its relations to technology or a general reader interested in the ways that technology impacts our romantic lives.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Studio Romantic on Shutterstock.

Contesting Moralities: Roma Identities, State and Kinship – review

In Contesting Moralities: Roma Identities, State and Kinship, Iliana Sarafian challenges established scholarly practices that attempt to define Romani identity, instead exploring how individuals navigate societal constraints with agency and resilience. Deftly combining ethnographic research, anthropological theory and personal reflection, this is an essential read for understanding the complexities of lived Roma experience, writes Martin Fotta.

The past decade has seen the publication of several high-quality monographs in various languages focusing on the lives, histories, and experiences of Romani people. While several have provided new insights into social processes, deconstructed existing preconceptions, or both, rarely has a book so subtly yet vehemently demanded that readers rethink their habits of thought about classical topics in Romani-related scholarship. This relatively short book by Iliana Sarafian, a talented anthropologist of Romani descent, does precisely this; it asks scholars to stop ruminating on who the Roma are and the character of ethnic boundaries, instead urging them to focus on how Romani individuals thrive within constraints and how they attempt to create spaces of survival for themselves and their families. It calls for exploring “experiences from the margins of Roma-ness” (98), but without presupposing to know what the core of Romani culture is.

The past decade has seen the publication of several high-quality monographs in various languages focusing on the lives, histories, and experiences of Romani people. While several have provided new insights into social processes, deconstructed existing preconceptions, or both, rarely has a book so subtly yet vehemently demanded that readers rethink their habits of thought about classical topics in Romani-related scholarship. This relatively short book by Iliana Sarafian, a talented anthropologist of Romani descent, does precisely this; it asks scholars to stop ruminating on who the Roma are and the character of ethnic boundaries, instead urging them to focus on how Romani individuals thrive within constraints and how they attempt to create spaces of survival for themselves and their families. It calls for exploring “experiences from the margins of Roma-ness” (98), but without presupposing to know what the core of Romani culture is.

Experimental in style and voice, Contesting Moralities is located within the ongoing effort to decolonise academic knowledge. The book is unique, however, in how the push to redefine the terms of representation in academic discourse is combined with solid ethnographic grounding and a commitment to anthropological theorisation. Weaving in self-reflection and personal narratives, it sheds light on broader social processes – on how racism, historical legacies, cultural traditions and social dynamics intersect in the lives of Romani individuals. It foregrounds individuals’ agency and the multifaceted nature of Romani experiences.

Weaving in self-reflection and personal narratives, [the book] sheds light on broader social processes – on how racism, historical legacies, cultural traditions and social dynamics intersect in the lives of Romani individuals.

The book is based on research in two pseudonymous Bulgarian Romani neighbourhoods – Radost and Sastipe – as well as in various state and non-state institutions. Sarafian is open about how practical circumstances and her position as a Romani woman influenced her research. For instance, she was assigned the role of a daughter when she first settled among non-kin and shut out from conversations of sexuality and intimacy among married women, as ignorance on such matters is expected from unmarried young Romani women. She does not treat these moments as constraints, however, but uses them as an opportunity to ponder social processes and patterning.

Sarafian is open about how practical circumstances and her position as a Romani woman influenced her research.

The main theme running throughout the book examines how Romani subjectivities are moulded by the state and its policies as they interact with values, practices, and relationships of kinship. The book focuses on a set of selected sites where the state has tried to interfere with Romani kinship, some of which are highly politicised and visible in everyday discourse: assimilation policies, control over fertility, disciplining of motherhood, and education of children. The book documents the scope of the state’s intervention and its violence past and present. “[T]here was no child in her Roma neighbourhood not going to some form of pansion [orphanage or a boarding school],” one of her research participants observes about life under the state socialism (85). The book charts the clash of state and kinship moralities and the contradictions this generates “inside” kinship relationships. It also documents various ways through which kinship resists the state or assimilates its initiatives.

Kinship, however, is not treated as a cultural artefact or tradition. Rather, the point that Sarafian tries to convey is that Romani kinship is oriented toward the future: weddings serve as communal projections of the potential for a better future, and childbearing reproduces this projection in the form of children. The concomitant aspect of this focus on becoming is Sarafian’s careful tracing of personal agency and capacity to aspire, even in moments where these could be the least expected, such as early marriages. At times, this struggle for self-determination is shown to be self-defeating. Such is the case of children, who take it upon themselves to protect their siblings and families from discrimination and racism, but in the process become further alienated from the educational system.

Romani kinship is oriented toward the future: weddings serve as communal projections of the potential for a better future, and childbearing reproduces this projection in the form of children.

The book is also a meditation on how, for people like Sarafian – who, in a move reproductive of antigypsyism, are sometimes dismissed as “Roma elite” – involvement in scholarship or activism becomes a mode to pursue authenticity and reflects their concern with the survival of Romani people. This dynamic generates its own contradictions, however. It threatens to co-opt Romani activists and scholars into co-constructing a figure of vulnerable and impoverished “hyper-real” Roma that would be legible to the state or development agencies. For many, in the context of racism and exclusion, these might be the only viable alternatives to achieve self-realisation while simultaneously connecting to their communities and responding to expectations from their families; for Sarafian, the book also becomes a way to connect with her family and community and to comprehend their position in contemporary Bulgaria. In a surprising twist, after she had been denied a job as a nurse at a local hospital, moved to work for an NGO, and then shifted to academia, Sarafian came to see a structural continuity between Romani activists, herself, and a woman who managed to become a doctor, but ruptured all relationships with her kin in the process: “I wanted to visit Ekaterina in Sofia to share that she was not alone, that there were other Roma who had managed to navigate the world within and outside of the Radost neighbourhood” (79).

The book’s style replicates its focus on the unfinished and ambiguous nature of social forms and processes, as well as the open-endedness of people’s aspirations. Rather than following one case study throughout the book or even through a chapter, each chapter is organised around a series of ethnographic stories and viewpoints. Some readers might find such a narrative approach difficult and desire some kind of synthesis or resolution. However, this is a deliberate writing strategy: “[W]hat there is still to say goes beyond the limits of this book” (101). The juxtaposition of fragments propels Sarafian’s description, sharpens her analysis, and invites future interpretations. Through ethnography, by highlighting particularities of various identifications or adding caveats to descriptions of kinship and state moralities, she constantly tries to re-articulate those social aspects that make a difference, often in ways she had not anticipated: “I found spaces, stories and examples of the everyday that challenged my preconceptions about Roma identifications” (11).

The chapter on education […] makes visible how any state effect is produced: in day-to-day interactions, in the intermeshing between institutional actions and everyday racialisation

My main objection to the book is that the state often comes across as a monolith. The only exception is the chapter on education, which makes visible how any state effect is produced: in day-to-day interactions, in the intermeshing between institutional actions and everyday racialisation, and in how teachers, directors, and schools translate policies, respond to economic constraints, and in turn shape the educational outcomes, and thus the futures, of Romani children – for better or worse. The book would have been much richer if such an approach had been reproduced in other chapters.

Sarafian is unapologetic and does not try to hide her motivations: “I wrote as I did because of the idiosyncrasies that have shaped me” (98). The result is a timely, readable book and an essential example of Romani autoethnography. Unlike Black autoethnographic writing, this genre remains underdeveloped in Romani-related scholarship, even in its critical iteration aimed at amplifying marginalised voices and empowering communities through challenging established forms of knowledge production. Contesting Moralities will therefore be of interest to those keen on understanding the complexities of being Romani in different contexts and to anyone interested in critical commentary on pressing social issues.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: Brum on Shutterstock.

Care Without Pathology: How Trans- Health Activists Are Changing Medicine – review

In Care Without Pathology: How Trans- Health Activists Are Changing Medicine, Christoph Hanssmann explores the evolution of trans therapeutics and health activism through ethnographic fieldwork conducted in New York City and Buenos Aires. Demonstrating how grassroots movements are disrupting social and biomedical power structures, the book is an essential contribution to research on depathologisation efforts in trans care, writes Robin Skyer.

Care Without Pathology: How Trans- Health Activists Are Changing Medicine. Christoph Hanssmann. University of Minnesota Press. 2023.

“The moves that would help the most transgender people the most? None of them are transgender specific”. Paisley Currah, praised political scientist and co-founder of the leading journal in trans* studies TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, stated what seems to be a fairly obvious point at a seminar in 2020. Yet, considering the ways in which dominant political and media discourses speak about trans* therapeutics (the term that the author of Care Without Pathology, Christoph Hanssmann, uses to describe the wide variety of gender-affirming care), trans* health, and hence trans* lives, are still considered to be an exception.

“The moves that would help the most transgender people the most? None of them are transgender specific”. Paisley Currah, praised political scientist and co-founder of the leading journal in trans* studies TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, stated what seems to be a fairly obvious point at a seminar in 2020. Yet, considering the ways in which dominant political and media discourses speak about trans* therapeutics (the term that the author of Care Without Pathology, Christoph Hanssmann, uses to describe the wide variety of gender-affirming care), trans* health, and hence trans* lives, are still considered to be an exception.

(Following Marquis Bey, in this article I use “trans*” – with an asterisk – as a disruptive term that perturbs ontological states. Most often, in Anglophone contexts, “trans” is used as an umbrella term to describe individuals whose gender identities expand beyond, subsume, or deny a binary structure. The use of the asterisk frees “trans*-ness” from its corporeal, nominalist ties. Instead, “trans*” becomes a function or expression; one that is neither predetermined nor limited in its scope.)

Hanssmann traces the shifting definition of trans* therapeutics, from 20th century transsexual medicine to contemporary crip, trans*-feminist informed healthcare infrastructures.

In Care Without Pathology, Hanssmann traces the shifting definition of trans* therapeutics, from 20th century transsexual medicine to contemporary crip, trans*-feminist informed healthcare infrastructures. In contrast to gay and lesbian depathologisation, Hanssmann notes, trans* activists and advocates have not looked for a divorce from medicine (as the tools for therapeutic care were, and continue to be, controlled by the state), but for a transformation of biomedical care structures. This is not to say that the movement seeks assimilation with, or inclusion within, current systems, but instead asks: what would it be like to receive the care we ask for, in the way that we need?

Care without pathology […] resists the damaging effects of legal, state, bureaucratic, and financial systems upon pathologised groups

Hanssmann emphasises how issues such as medical gatekeeping and self-determination in care settings are the result of hegemonic power relations; issues that many (multiply-)marginalised groups face in their interaction with biomedical practice. Care without pathology, he argues, calls not only upon a broader change of healthcare infrastructures, but resists the damaging effects of legal, state, bureaucratic, and financial systems upon pathologised groups. As such, trans* health activism has more in common with disability and feminist movements, as they contest hierarchies of power and systemic harm within the constraints of the present.

As an ethnographic study, Care Without Pathology is founded upon eight years of research in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and New York City, USA. Hanssmann argues that by choosing locations in both the Global South and the Global North, he was able to engage in “transhemispheric discursive inquiry” (17), an approach that leans away from a standard comparative study by acknowledging the interactions and relations between research sites. Although I would contest Hanssmann’s use of this oversimplified dichotomy, his choice of locations enables us to explore different contexts in which major changes in the regulation of trans* therapeutics were taking place between 2012 and 2018.

In Argentina, 2012 saw the passing of the Gender Identity Law, which removed the requirement of a diagnosis for trans* therapeutics. In 2013, the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) by the American Psychiatric Association removed “Gender Identity Disorder” from their guidelines and included a new diagnostic classification: ‘Gender Dysphoria’, which advocates saw as a positive step toward depathologisation. Hence, Care Without Pathology spans a period of significant transformation, the effects of which are continuing to unfurl. Moreover, Hanssmann draws upon ethnographic observations and interviews, ensuring that the voices of social workers, community members, activists and advocates resonate throughout the book.

Hanssmann draws upon ethnographic observations and interviews, ensuring that the voices of social workers, community members, activists and advocates resonate throughout the book.

Hanssmann describes vivid examples of grassroots activism and its volatile association with political compromise. Chapter Three, for example, focuses upon the use of epidemiological biographies by community-based researchers in Buenos Aires. This involved the combining of biographical data with statistics, creating visuals and information about the effects of violence and discrimination upon the health and lives of travesti and trans* people. Through this method, organisers were able to leverage political focus upon Argentinian state responsibilities for premature deaths, as well as institutionalised neglect and violence with regards to employment, healthcare, and housing. However, as Hanssmann highlights, this use of statistical collectivisation, and the concept of “population”, are closely associated with state power, structural violence, and trans* necropolitics.

[The] use of statistical collectivisation, and the concept of “population”, are closely associated with state power, structural violence, and trans* necropolitics

This is particularly salient for travesti, for whom the subsuming of their livelihoods, identities, and culture under a wider trans* umbrella is colonial oppression. (I urge readers to review the work of Malú Machuca Rose, who writes about travesti and resistance to colonial usage of the word; as well as the works of Giuseppe Campuzano and Miguel A. López.) It is through the discussion of these conflicting ideas that Care Without Pathology deftly illustrates the complexity of struggles for change.

Another example is outlined in Chapter Four, where Hanssmann describes the “narrow passageways of action” (149) used to contest Medicaid exclusion. Activists and advocates pressed for access to trans* therapeutics by using the language of state authorities that spoke predominantly of economic risk. They highlighted the negative effects of austerity measures and reframed the narrative around trans* therapeutics as a public good. Nevertheless, as Hanssmann explains, by utilising a method that draws upon human capital and the politics of investment, one may ask whether more harm may be caused (or left to fester), through an adherence to these neoliberal conceptions. It seems antithetical to use economic value as a measure for the “worthiness” of lives, when coalitional social change is what you are striving for.

What happens when trans* people seek to distance themselves from biomedical and state institutions, and find self-supporting solutions?

Hanssmann acknowledges that there has been a narrative shift from trans* health to trans* wellness, a change that reflects depathologisation efforts. He also mentions the work of scholars such as Cameron Awkward-Rich, Hil Malatino, and Andrea Long Chu, who highlight the constitutive pain and negativity of trans*-ness as a counter to “curative” discourse surrounding trans* therapeutics. Yet what could expand upon Hanssmann’s work is an exploration of self-procurement and therapeutic experimentation. What happens when trans* people seek to distance themselves from biomedical and state institutions, and find self-supporting solutions? Consequently, we may ask whether the term “trans* therapeutics” is appropriate to describe trans* care practices. It is in this area that my own PhD research is situated. My current research approaches the topic of trans* care through qualitative, participatory techniques and looks to complement Hanssmann’s analysis.

Where Care Without Pathology succeeds is through the presentation of trans* activisms that have acknowledged the epistemological ties between groups and individuals that are labelled as “an exception”. By demonstrating how the politics of difference creates harm through biomedical structures and other systems of power, Hanssmann highlights the need for coalitional activism in the struggle for social change, and as resistance to neocolonialism. It is an excellent addition to the reading lists of scholars, activists, and indeed, anyone interested in social movements, queer studies and the sociology of care.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Ross Burgess on Wikimedia Commons.

Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage – review

In Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage, Michael Herzfeld considers how marginalised groups use nationalist discourses of tradition to challenge state authority. Drawing on ethnography in Greece and Thailand, Olivia Porter finds that Herzfeld’s concept of subversive archaism provides a useful framework for understanding state-resistant thought and activity in other contexts. A longer version of this post was originally published on the LSE Southeast Asia Blog.

Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage. Michael Herzfeld. Duke University Press. 2022.

“The nation-state depends on obviousness because, in reality, its own primacy is not an obvious or logical necessity at all. It is presented as a given, and most people accept it as such. Implicitly or explicitly, subversive archaists question it” (123).

“The nation-state depends on obviousness because, in reality, its own primacy is not an obvious or logical necessity at all. It is presented as a given, and most people accept it as such. Implicitly or explicitly, subversive archaists question it” (123).

The excerpt above encapsulates the central thesis of the social anthropologist and heritage studies scholar Michael Herzfeld’s Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage. That being said, that the modern nation-state is widely accepted as the primary unit of territorial and cultural organisation, but that there are a group of people, subversive archaists, who question this rhetoric. Subversive archaism challenges the notion that the nation-state, constrained by bureaucratic organisation and with an emphasis on an ethnonational state, is the only acceptable form of polity. Subversive archaists offer an alternative polity, one legitimised by understandings of heritage that date back further than the homogenous ‘collective heritage’ proposed in state-generated discourses for the purpose of creating a ubiquitous representation of national unity (2). As Herzfeld suggests, subversive archaists instead reach into the past to reclaim older and often more inclusive polities and understandings of belonging, and in doing so, they utilise ancient heritage to challenge the authority, and very notion, of the modern nation-state.

Subversive archaists instead reach into the past to reclaim older and often more inclusive polities and understandings of belonging

Herzfeld examines the concept of subversive archaism through comparative ethnography, drawing on long-term ethnographic fieldwork with two communities: the Zoniani of Zoniana in Crete, Greece, and the Chao Pom of Pom Mahakan, Bangkok, Thailand. At first, the two communities appear geographically and culturally distinctively dissimilar. However, they share one important feature neither country has ever been officially colonised by a Western state. Herzfeld ascribes the term “crypto-colonialism”, a ‘disguised’ form of colonialism, to both Greece and Thailand, as states that despite never being officially colonised, were both under constant pressure to conform to Western cultural, political, and economic demands. Herzfeld explains that such countries place a great emphasis on their political independence and cultural integrity having never been colonised, yet many forms of their independence were dictated by Western powers.

In identifying themselves with the heroic past of the nation state, [subversive archaists] legitimise their own status as rightful members of the nations in which they now find themselves marginalised.

In Chapter Two, Herzfeld explores the historical origins of the images and symbols mimicked by subversive archaists to challenge the dominant, often ethnonationalist, narrative of the nation-state. Subversive archaists ransack official historiography and claim nationalist heroes as their own, and in identifying themselves with the heroic past of the nation state, they legitimise their own status as rightful members of the nations in which they now find themselves marginalised. Rather than reject official narratives, subversive archaists appropriate them, in ways that undermine state bureaucracy. For example, the Zoniani (and many Cretans) do not reject the official historiography of the state, which emphasises continuity with Hellenic culture. In fact, they fiercely defend it, and go one further, by citing etymological similarities between Cretan dialects that bear traces of an early regional version of Classical Greek. In doing so, they make claims that they have a better understanding of history than the state bureaucrats.

Chapter Three explores belonging and remoteness through kinship structures and geographical location. Herzfeld highlights how the nation-state uses the symbolic distancing of communities as remote or inaccessible as a tool to marginalize communities. Pom Mahakan is located on the outskirts of Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, and nowadays Zoniana is accessible by road. Herzfeld argues that the characterisation of these communities as remote and inaccessible is applied by hostile bureaucracies rather than by the communities themselves as an extreme form of intentional political marginalisation.

Zoniani society is still structured by a patrilineal clan system, and Chao Pom society by a mandala-based moeang system. These structures represent an older, and alternative, system of polity to the modern bureaucratic nation-state.

In Chapter Four, Herzfeld proposes that we reframe the assumption that religion shapes cities and instead think about how cosmology shapes polities. In particular, how Zoniani society is still structured by a patrilineal clan system, and Chao Pom society by a mandala-based moeang system. These structures represent an older, and alternative, system of polity to the modern bureaucratic nation-state. For example, the Chao Pom embrace religious and ethnic minorities, arguing that diversity is representative of true Thai society, and that tolerance and generosity are true Thai ideals. The notion of polity itself is the focus of Chapter Five which explores how Pom Mahakan and Zoniana have cosmologically distinct identities that, when conceptualised as part of the same system as the nation-state, both mimic and challenge the state’s legitimacy, thus inviting official violence.

Herzfeld argues that what sets subversive archaists apart from the “state-shunning groups” described by Scott […] is their ‘demand for reciprocal respect and their capacity to play subversive games with the state’s own rhetoric and symbolism’

Herzfeld explains how neither the Zoniani nor Chao Pom fit into the James C. Scott’s concept of “the art of not being governed,” applied to Zomian anarchists who flee from state centres into remote mountainous regions in northeastern India; the central highlands of Vietnam; the Shan Hills in northern Myanmar; and the mountains of Southwest China. Herzfeld argues that what sets subversive archaists apart from the “state-shunning groups” described by Scott, but also makes them representative of a widespread form of resistance to state hegemony, is their “demand for reciprocal respect and their capacity to play subversive games with the state’s own rhetoric and symbolism”. Arguably, the reason that the Zoniani and Chao Pom can demand ‘reciprocal respect’ is related to their ethnic, historical, and cultural affiliation with the majority that marginalises them. The ethnic minorities of Zomia do not benefit from the same types of affiliation.

Ultimately, Herzfeld’s model of subversive archaism offers us an example of understanding how marginalised groups challenge and subvert authority

Ultimately, Herzfeld’s model of subversive archaism offers us an example of understanding how marginalised groups challenge and subvert authority. Herzfeld is not proposing that any given group needs to fit neatly into the category of subversive archaists, but rather how some groups reach back into the past to offer an alternative future. In Chapter Eight, Herzfeld explores the future of subversive archaist communities, and also how subversive archaism might mutate into nationalist, and potentially dangerous, movements. The Chao Pom embrace ethnic and religious minorities on the grounds that acceptance and inclusion are true Thai ideals. However, there are dangers to invoking ideologies attached to ‘true’ ideologies of national cultures and traditions, and other types of communities can utilise the rhetoric of subversive archaism. For example, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, “antimaskers” use the language of “liberty” and “democracy” against the modern bureaucratic state, seeking to transform the present into an idealised national past.

I was initially sceptical about who qualified as a subversive archaist. At first, the term seemed too rigid, a community had to be marginalised by the state authority, but associate themselves with the majority and use the language of the state to legitimise themselves their alternative polity. Then, the term seemed too broad, it is not specific to a certain geography, ethnic identity, or religion, and can apply to religious and non- religious groups. Subversive archaism might help us make sense of the Chao Pom and the Zoniani, but who are the subversive archaists of the contemporary world? Then, one morning, when listening to a podcast from the BBC World Service covering the inauguration of India’s controversial new parliament building, I heard a line of argument, from the Indian historian Pushpesh Pant, that struck me as being rooted in subversive archaism.

When asked about the aesthetics of the new parliament building, Pant remarked “I think it is a monstrosity… If the whole idea was to demolish whatever the British, the colonial masters, had built, and have a symbolic resurrection of Indian architecture, I would even go, stick my leg out and say Hindu architecture, it should have been an impressive tribute to generations of Indian architectural tradition Vastu Shastra. Vastu Shastra is the Indian science of building, architecture.” He goes on to say: “How does this symbolise India?”

I suspect that given the rise of nationalist movements across the globe, the tools of subversive archaism, rather than subversive archaists groups per se, will become all the more visible.

In invoking the Vastu Shastra, the ancient Sanskrit manuals of Indian architecture, and the Sri Yantra, the mystical diagram used in the Shri Vidya school of Hinduism, Pant demonstrates his deep understanding of ancient Indian architecture and imagery. And in doing so, he highlights the missed opportunities of the bureaucratic state in designing their new parliament building to create a building that was truly representative of archaic Indian architecture. He does what Herzfeld describes as “playing the official arbiters of cultural excellence [here, the BJP] at their own game”. I suspect that given the rise of nationalist movements across the globe, the tools of subversive archaism, rather than subversive archaists groups per se, will become all the more visible.

This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books blog as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia. This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the LSE Southeast Asia Blog, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image Credit: daphnusia images on Shutterstock.

The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions – review

In The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions, Adam Kuper interrogates the history of anthropological museums and considers questions of colonialism, race, and cultural appropriation around the artefacts they hold. As these institutions face a moment of global reckoning, Kuper offers a balanced, nuanced book on the historical and evolving role of museums, writes Tim Chamberlain. … Continued

The Spirits of Crossbones Graveyard

The book's author Sondra Hausner (Professor of Anthropology, University of Oxford) will explore the issues raised in her book. Every month, a ragtag group of Londoners gather in the site known as Crossbones Graveyard to commemorate the souls of medieval prostitutes believed to be buried there—the “Winchester Geese,” women who were under the protection of the Church but denied Christian burial. In the Borough of Southwark, not far from Shakespeare's Globe, is a pilgrimage site for self-identified misfits, nonconformists, and contemporary sex workers who leave memorials to the outcast dead. Ceremonies combining raucous humor and eclectic spirituality are led by a local playwright, John Constable, also known as John Crow. His interpretation of the history of the site has struck a chord with many who feel alienated in present-day London. Sondra L. Hausner offers a nuanced ethnography of Crossbones that tacks between past and present to look at the historical practices of sex work, the relation of the Church to these professions, and their representation in the present. She draws on anthropological approaches to ritual and time to understand the forms of spiritual healing conveyed by the Crossbones rites. She shows that ritual is a way of creating the present by mobilizing the stories of the past for contemporary purposes.

The book's author Sondra Hausner (Professor of Anthropology, University of Oxford) will explore the issues raised with:

Bridget Anderson (Professor of Migration and Citizenship, University of Oxford)

Diane Watt (Professor of Medieval Literature, University of Surrey)

Chair: Antonia Fitzpatrick (Departmental Lecturer in History, University of Oxford)