civic engagement

3 Cities That Became Better Places for Young Black Men

Less than 24 hours after Trayvon Martin was shot and killed in Florida as he returned home with a bag of Skittles, then-President Barack Obama addressed a rattled nation. Standing among a group of Chicago-area teens, he announced the launch of My Brother’s Keeper, an initiative to address the persistent opportunity gaps faced by boys and young men of color, and to ensure all young people can reach their full potential.

“I firmly believe that every child deserves the same chances that I had,” said Obama from a podium in the White House’s East Room. “That’s why we’re here today. To do what we can, in this year of action, to give more young Americans the support they need to make good choices and be resilient, and to overcome obstacles and achieve their dreams.”

Martin’s death became a catalyst for a national reckoning against structural racism, prompting many cities to respond with efforts to uplift communities of color. Some have shown signs of success; others have fallen short. But ten years after its launch, My Brother’s Keeper, now known as the MBK Alliance, has seen remarkable progress in three cities in particular, helping them prove that the power of collaboration can solve deeply entrenched problems that have plagued America for decades.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Serving as a financial and advisory resource, MBK Alliance helps foster collaborations between cities to achieve progress across six milestones identified as keys to young people’s future success: early childhood education, reading at grade level by the end of third grade, graduating from high school, completing a post-secondary education or training, getting a job and staying safe from violence.

Backed by the power of the nationwide collective, three “Model Communities” have emerged as standouts in achieving these goals: Newark, New Jersey; Omaha, Nebraska; and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Here’s a glimpse into how they did it.

Newark

Eleven years ago, Newark, with 112 homicides, had the third highest murder rate in the nation, as gun violence wracked the city’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods.

By last year that number had plummeted to 47, the lowest number of homicides in 60 years, and continuing a trend of sharply falling violent crime rates in New Jersey’s biggest city. The year prior, in 2022, Newark saw fewer homicides than it had since 1961. And two years before that, in 2020, not a single shot was fired by a police officer in Newark all year.

“The larger ecosystem in Newark working to improve public safety came together and got to work,” explains Mark Comesañas, executive director of My Brother’s Keeper Newark, which functions as an initiative of the Newark Opportunity Youth Network.

The fruits of that labor came during a crucial time, as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and George Floyd protests collided to shine a light on the nation’s inequities.

Mayor Ras Baraka, a son of the city, reappropriated five percent of the police budget to fund violence prevention work. Newark launched a new Office of Violence Prevention and Trauma Recovery, which uses data analysis, anti-racism and hate crime units, victim support, partnerships between police and social workers, and other proven public health approaches to increase safety. And the Newark Community Street Team, which deploys outreach workers and high-risk interventionists to mediate disputes and stop bloodshed, now works with youth most at-risk to perpetrate or become a victim of violence.

“Newark is no longer on the ‘top 10 most violent city list,’ where it had a coveted position for almost 50 consecutive years,” Street Team founder Aqeela Sherrills recently told Yahoo! News.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Most importantly, says Comesañas, also born and raised in Newark, young people, often left out of discussions aimed at understanding their challenges, now sat at the table, participating in public forums on crime and meeting with elected officials. Their success has influenced advocates to reach back further to engage youth as young as 13, he adds.

“Young people are our community’s greatest untapped resource,” he said. “Instead of seeing them as a problem to be solved we saw them as an asset in solving those problems.”

Being an MBK Alliance Model Community has allowed Comesañas and others from Newark to share their experiences, while also learning from the wins and losses of other cities, he says. For instance, his organization gleaned lessons from New York’s Young Men’s Initiative and NYC Men Teach, and an action guide from Sacramento that helped to fine tune efforts in Newark.

Still, Comesañas knows the work is not done.

“Our next phase is to ensure there’s even greater integration across all systems,” he says. “We need City Hall, community orgs and charter schools all working together and having conversations; we need to hear from more young people.”

Tulsa

Being named a My Brother’s Keeper Model Community in 2023 didn’t turn the community in Tulsa, Oklahoma, complacent. It inspired them to do more.

“We’ve activated nearly 100 more partners since becoming a Model Community, working to understand experiences of Black young men and boys of color through the milestones,” said Ashley Philippsen, executive director of Impact Tulsa, which leads local MBK efforts.

Tulsa earned its Model Community status for the strides it made towards the first predictor of success identified by My Brother’s Keeper: early childhood education.

Oklahoma began offering universal preschool education in 1998, yet several years ago thousands of children in Tulsa County, including more than 1,000 in the City of Tulsa, were not enrolled, Philippsen says. Changing that required the convening of residents, community organizations, city and county departments, businesses, and the school district, among others.

“Together, we had to shift the narrative around preschool education,” Philippsen says.

Credit: Shutterstock

Credit: Shutterstock

Clergy, daycare teachers, parents and schools formed teams and went door-to-door, armed with data they had collected to better understand the factors keeping kids out of preschool. “We used data as a flashlight to help our partners identify and remove roadblocks for young people in underserved communities,” Philippsen says.

They paired this face-to-face persuasion with a mass media campaign that purchased space on billboards and aired commercials on television. Churches and others preached a new awareness about the benefits of early education, while also addressing barriers to enrollment, such as a lack of programs in underserved neighborhoods.

To better understand the complex challenges of students in Tulsa, the Tulsa Child Equity Index, a project of Impact Tulsa and Tulsa Public Schools, was created in 2018 to pinpoint areas of need. The index includes data on 14 different neighborhood indicators, including gun violence, employment rate, walkability, educational attainment and socioeconomic status. Each helps to identify structural and systemic barriers, intersections between opportunity and access, Philippsen explained.

“It helps to build a deeper understanding of the factors that impact students in certain neighborhoods,” she said.

As a result of these efforts, enrollment in early childhood programs in Tulsa increased from 65 percent of eligible students in 2013 to 82 percent in 2020, and attendance overall for students of color rose by 33 percent. And while some of those gains were lost amid the pandemic, the benefits of involvement with My Brother’s Keeper, particularly as a model community, continue.

“It’s really been powerful to be part of this national network, learn from each other and share best practices so that other cities can experience the same successes,” Philippsen says.

Omaha

When Mississippi-born William Barney moved to Omaha, Nebraska, 24 years ago, he saw many of the problems he’d become familiar with as he traveled the country identifying strengths and struggles in African American communities.

Among the challenges, he said, were high levels of gun violence, low graduation and employment rates, and housing challenges.

He got to work, launching the African American Empowerment Network, a convener for those looking to solve issues that impact the Black community.

“We started by talking to a few people about things we could do together to improve conditions here,” Barney says, recalling conversations he had with pastors, residents and others.

Since then those talks have multiplied. Church visits and door-to-door chats became formal sit-downs with nonprofits, businesses, Omaha Public Schools, the police department, elected officials and many more, Barney says.

“We listen to each other, facilitate on collective tables, and develop plans to create change,” he adds.

Credit: Shutterstock

Credit: Shutterstock

Those talks have led to action, like a partnership between the school district and more than 40 organizations. Some 500 youth are now enrolled in Step-Up Omaha, a summer employment and training program for 14-to-21 year olds. And the Empowerment Network has worked to expand employment programs, foster civic engagement among youth and other residents, increase exposure to STEM fields and reach other diverse communities, including Latinx, Native American and Asian groups.

The outcome? Graduation rates rose and the unemployment rate plummeted, Barney said. Shootings are down with homicides dropping by 33% since 2011. And Omaha 360, an initiative of the Empowerment Network, is now recognized nationally as a model for violence prevention and intervention.

None of this work can be done in silos, he explains.

“No one individual, organization or business can solve these problems themselves,” Barney said. “We have shown that we can only create change by working together.”

The post 3 Cities That Became Better Places for Young Black Men appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Friendly Mentors Help Ukrainians Find Their Footing in Vilnius

“Coming from another country, you find yourself in a completely unusual location and amongst completely different people. Everything is unfamiliar and you, like Alice in Wonderland, walk and watch.”

That’s how Anastasija Kostenko summed up what it was like arriving in Vilnius, Lithuania, in 2022, having traveled over 700 miles to flee the destruction and devastation in Ukraine caused by the Russian invasion.

Needing to start a new life but not knowing where to begin, Anastasija signed up to become a mentee in the city’s BeFriend Vilnius program, run by International House Vilnius, an organization aimed at helping foreign newcomers find a “soft landing.” The program matches foreign mentees with local mentors, with pairs encouraged to meet at least twice a month.

BeFriend Vilnius was founded to help Ukrainian refugees feel more at home in Lithuania, but also to find a social way of fielding their questions. Courtesy of BeFriend Vilnius

BeFriend Vilnius was founded to help Ukrainian refugees feel more at home in Lithuania, but also to find a social way of fielding their questions. Courtesy of BeFriend Vilnius

Anastasija’s mentor Rūta and Rūta’s friend helped her navigate what seemed like a never ending array of forms and applications. “Were it not for them, it would have been incredibly difficult to arrange a huge number of documents and top priority issues,” Anastasija told BeFriend Vilnius coordinators.

“It’s been a matter of filling out documents, applying for grants and applying for payments and payment cards. I am sincerely grateful for their help with some really important issues. I would not have understood them myself.”

Anastasija and Rūta, who have not shared last names for privacy reasons, are part of an initial cohort of around 500 Ukrainian mentees and Vilnian mentors. They were matched by BeFriend Vilnius during the first iteration of the program in 2022, initially designed to help the influx of Ukrainians find their footing amidst a new culture and language.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

With a population of around 86,000, Ukrainians are now the largest foreign community in Lithuania, making up around 3.2 percent of the country’s overall population of about 2.7 million.

For International House Vilnius project manager Agnė Goldbergaitė, who has been project manager at BeFriend Vilnius since the beginning, the original idea was not only to make Ukrainian refugees feel more at home in Lithuania, but also to find a social way of fielding the inevitable influx of questions around basic information.

“When Ukrainians first started coming to Lithuania, there was a huge flow of people needing all kinds of information, like how to register for a doctor’s appointment, how to find a school for their children, how to buy tickets for the public buses or even where to drink coffee,” says Goldbergaitė. “They were really just in need of a friend.”

“Every time we host an event, we’re surprised at how many different countries people come from,” says Agnė Goldbergaitė. Courtesy of Befriend Vilnius

“Every time we host an event, we’re surprised at how many different countries people come from,” says Agnė Goldbergaitė. Courtesy of Befriend Vilnius

“We decided that they could register with us, and share a bit more about themselves, whether they are a single mom with two kids, or a young woman who is into photography. We then connect them with a local Vilnian with a similar situation or interests, to try and lift some of that burden from the government institutions that are also taking care of them. So many of our first mentors joined because they wanted to help Ukrainian people coming from the war.”

Another mentor/mentee pair is Irina and Jovita. Irina came from Ukraine with her eight-year-old daughter, and she met Jovita within a week of her arrival in Lithuania. Jovita’s 11-year-old son comes up with the activities and meeting places, and while the moms are able to communicate in Russian, the kids speak to each other in English, supplemented with hand gestures.

Meanwhile, mentor Kristina was initially anxious about whether she could provide the help her mentee, Iryna, would need. But when they met, she was reassured to hear that Iryna was simply looking for someone to talk to. “I’ve met a great person who I’m now very happy to call my friend,” she told the program. Vilnius local Jurga has also been offering in-depth emotional support to Ukrainian Eteri, and the two have developed a strong bond.

Seeing how well the program has worked, coupled with Vilnius’ overall increasing attractiveness to migrants, the BeFriend Vilnius team expanded the program last year to all foreign newcomers. It also moved away from the time-consuming process of hand-matching mentors and mentees, instead developing a website with the ability to match pairs based on their circumstances and interests. Since the initial launch, BeFriend Vilnius has been receiving up to 15 applications per week for mentors and mentees.

BeFriend Vilnius pairs, from left: Jovita and Irina; Jurga and Eteri; and Kristina and Iryna. Courtesy of BeFriend Vilnius

BeFriend Vilnius pairs, from left: Jovita and Irina; Jurga and Eteri; and Kristina and Iryna. Courtesy of BeFriend Vilnius

“We realized this would actually be the best thing for all foreigners. There are around 73,000 international people living in Vilnius at the moment, making every ninth Vilnius resident a foreigner. Our city is becoming more international,” says Goldbergaitė.

“Every time we host an event, we’re surprised at how many different countries people come from — Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ecuador, Philippines, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Georgia — all kinds.”

The number of foreigners living in Lithuania has risen rapidly, totaling 203,157 as of September 2023, up from the 145,118 recorded in 2022. This is partly due to local marketing efforts. The tongue-in-cheek “Vilnius: the G-Spot of Europe” campaign hit global headlines, while government-funded organizations Work in Lithuania and Invest Lithuania have made it their mission to attract skilled foreign workers to the country. Visa processing times have been cut from eight months to just one, and there’s even an arrival allowance of €3,444 (around $3,764) awarded to migrants in high-value occupations considered to be in local shortage.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Quality of life in Lithuania also appeals to migrants: It’s in the top 25 percent of the world’s safest countries and has 15 public holidays a year, the second-highest number in the EU. Just one percent of employees work very long hours — well below the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development of 38 countries) average of 10 percent — ranking it 11th for work-life balance in this group.

The next evolution of BeFriend Vilnius will be to complement the mentoring initiative with a more formal integration program of events and seminars.

“Vilnius is super compact and understandable, and if you take just two steps outside the city, you’re in the forest. Everyone speaks English, and most people do love it,” says Goldbergaitė. “We want people to fall in love with Vilnius and thrive here. We’re always excited to have an impact on real people, and build our community.”

The post Friendly Mentors Help Ukrainians Find Their Footing in Vilnius appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power – review

Caty Borum‘s The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power considers how comedy intersects with activism and drives social change. Borum’s accessible text draws from case studies and personal experience to demonstrate how comedy can successfully challenge norms, amplify marginalised voices and foster dialogue on issues from racism to climate change, writes Christine Sweeney.

Can you teach comedy? Can a sense of humour, charisma, delivery, stage presence and timing be learned? Comedy programmes popping up in universities across the world would say, “Yes, yes it can”. If the question is, “can you teach comedy as a tool for social change and civic power?”, Caty Borum has an entire book which aims to provide an answer.

Can you teach comedy? Can a sense of humour, charisma, delivery, stage presence and timing be learned? Comedy programmes popping up in universities across the world would say, “Yes, yes it can”. If the question is, “can you teach comedy as a tool for social change and civic power?”, Caty Borum has an entire book which aims to provide an answer.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power by Caty Borum explores the intersection of comedy and social activism, delving into the question of whether comedy can be taught and used as a tool for social change. Borum discusses the role of creativity, cultural power, and participatory media in driving social change and how postmillennial social-justice organisations collaborate with comedians. Serving as a follow-up to Borum’s work co-written with Lauren Feldman in 2020, A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice, this new book is a how-to manual with case studies on integrating comedy into social justice efforts.

[The] book is a how-to manual with case studies on integrating comedy into social justice efforts.

Borum reflects on her own comedy career, drawing from experiences working with sitcom legend Norman Lear on get-out-the-vote campaigns in the late ’90s and early 2000s like Declare Yourself. While these campaigns engaged young people and demonstrated the power of comedic efforts, Borum notes that the impact on electoral outcomes was limited. Though 2004 saw the largest turnout (nearly 50 per cent) of voters aged between 18 and 24, that demographic still accounted for just 17 per cent of the total voter population, and Bush beat his democratic rival John Kerry to secure a second term.

Although mobilising the public through comedy for direct political action may be too great an ask, Borum emphasises comedy’s narrative power in shaping public understanding and influencing cultural attitudes. The book explores the evolution of comedy in the participatory media age, especially its increased visibility during the pandemic and its role in challenging societal norms. The rise of independently produced content on social media has challenged the authority of networks and studios, boosting the democratisation and creative agency of comedy “content”. Though Borum acknowledges the benefits of social media for amplifying marginalised creators, she falls short of critically examining its impact on mental health, the spread of misinformation and biased algorithms. Despite this, she underscores comedy’s potential as a cultural intervention empowered by the participatory networked media age.

Positive deviance, according to Borum, is the quiet power of comedy that journalism lacks.

The book discusses the comedic response to political events, particularly the rise of Donald Trump, positioning comedy as a force for social change by offering fresh ways of undermining the status quo. According to Borum, comedians say what journalists cannot, thinking of Michelle Wolf, who at the 2018 White House Correspondents dinner pointed out the mutually beneficial cycle of journalists covering then-President Trump’s near-constant news feed. Positive deviance, according to Borum, is the quiet power of comedy that journalism lacks.

Comedy also serves as a creative space for marginalised voices, providing an alternative narrative and critique that traditional journalism may lack. Borum highlights the importance of optimism in comedy. Comedy provides a space for an alternate reality, for example the TV series Schitt’s Creek portrays a world where the LGBTQ community is fully accepted. In this sense, optimism can be a survival tactic. As Borum suggests,

[C]omedy as a force for social justice breaks down social barriers and opens space to discuss taboo topics; persuades because it is entertaining and makes us feel activating emotions of hope and optimism; serves as a mechanism for traditionally marginalized people to assert and celebrate cultural citizenship through media representation; acts as both social critique and civic imagination to envision a better world; and builds resilience to help power continued struggle against oppression.

Borum provides an in-depth, well-researched review of cultural entertainment activists, tracking the power of the entertainment industry to affect how people feel. “Pioneering cultural entertainment activists pushed for ‘mainstreaming’ oppressed people – including and normalizing their lives and lived experiences in entertainment.”

The book is something of a documented workshop, drawing from the experiences and insights of leaders across social justice activism and comedy to emphasise the power of media.

The book is something of a documented workshop, drawing from the experiences and insights of leaders across social justice activism and comedy to emphasise the power of media. Its instructive aspect lies in Borum’s description of running comedy workshops and writers’ rooms, offering a practical guide for both comedians and social activists. These collaborative spaces aim to translate key messages into comedy routines through storytelling, making complex issues more accessible. The author uses climate change and the opioid epidemic as examples, demonstrating how comedy can humanise and mobilise audiences to address pressing challenges.

Borum examines a case study of youth political activist group Hip Hop Caucus which aims to communicate a basic awareness of climate change to Black, Indigenous, and other People of Colour, who are the most affected by, and yet contribute the least to, climate change in the US (and globally). Even if this comedy work may not reach the oil companies responsible for the brunt of climate change, it serves to educate and mobilise audiences. In this sense, the messaging of the book goes, culture is important because it is the mechanism by which we relate to each other. Although it’s hard to demonstrate the material impact of comedy and the entertainment industry overall on political dynamics, communicating the mechanisms translating individual experiences in collective narrative storytelling to foster understanding and support is convincing.

Culture is important because it is the mechanism by which we relate to each other.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious emphasises the power of comedy as a force for social justice and provides practical insights into its integration with activism. She effectively shows how collaboration between the two has the power to start meaningful conversations around racism, climate change, economic disenfranchisement, addiction and more. Borum’s work serves as a valuable guide for media and communication theorists, entertainment industry professionals, social activists, and comedians, showcasing the potential of collaboration between comedy and activism in sparking meaningful conversations on various societal issues.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image Credit: Paul Craft on Shutterstock.

Banking the Most Valuable Currency: Time

David Gill might be the richest man in Sebastopol, California. The semi-retired health care administrator is banking the most valuable currency in the world: time. Gill currently has 480 hours in his savings account at the local time bank, “and I haven’t even registered any of my hours in 2023,” he says.

In brief, a time bank does with time what other banks do with money: It stores and trades it. “Time banking means that for every hour you give to your community, you receive an hour credit,” explains Krista Wyatt, executive director of the DC-based nonprofit TimeBanks.Org, which helps volunteers establish local time banks all over the world. Nobody keeps track of the exact number, but thousands of time banks with several hundred thousand members have been established in at least 37 countries, including China, Malaysia, Japan, Senegal, Argentina, Brazil and in Europe, with over 3.2 million exchanges. There are probably more than 40,000 members in over 500 time banks in the US.

Steve Bursch (with red rake) and fellow time bankers beautify the library grounds for the City of Sebastopol. Credit: Marty Roberts / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Steve Bursch (with red rake) and fellow time bankers beautify the library grounds for the City of Sebastopol. Credit: Marty Roberts / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

In Sebastopol, 250 residents have time bank accounts where they save and withdraw hours as needed. For instance, Gill, who is also the main local time bank coordinator, likes to offer his expertise with computer programming, editing and financial planning. In return, he asks for help when he needs a ride to the airport or someone to transport heavy furniture. He rattles off the first few of many examples: “Steve, who lives on the next block, drove me and my partner to the Santa Rosa airport. Ken fixed the icemaker in our refrigerator, and Elaine did some electrical work.”

If he had called professional repair and taxi services, the expense would have been significant. However, the interest, so to speak, goes beyond the value of a mere transaction. The time banks are building social capital. “I’ve made wonderful friends I wouldn’t have met otherwise and we now invite each other to our garden parties,” says Gill. “It’s about making community and being a part of the community. You can’t put a price on that stuff.”

David Gill came to the time bank like most of his neighbors. He doesn’t remember where he first heard about it a few years ago, but he immediately thought it was a great idea. He signed up, started using it, and when the founders asked for help, he stepped up. He gets paid in the currency he values most: hours.

Many time banks are volunteer community projects, but the one in Sebastopol is funded by the city and operates under the nonprofit status of the Community Cultural Center. After all, time is money. “Every volunteer hour is valued around $29,” Wyatt calculates. “Now think about the thousands of dollars a city saves when hundreds of citizens serve their community for free.” The Sebastopol time bank has banked more than 8,000 hours since its launch in 2016. Members might reimburse each other for costs — for instance, gas mileage or materials — but the service itself and the membership are always free.

Time bank members in the Netherlands participate in a DIY electronics course. Credit: Timebank.cc

Time bank members in the Netherlands participate in a DIY electronics course. Credit: Timebank.cc

Some cities look to time banks as a model to support an aging population. In St. Gallen, Switzerland, only members over the age of 50 may join the local Stiftung Zeitvorsorge, or “Foundation Time Care,” which was founded in 2011 and has 320 members who have banked more than 80,000 hours. While Sebastopol’s time bank is more geared toward practical services to fill a gap other community services don’t address, members in St. Gallen regularly help seniors run errands, shop for groceries, take them to the doctor or simply keep them company. Here, too, the city guarantees the program, hoping that it will help seniors to stay in their homes and live independently longer because 75 percent of locals said in a poll that they hoped to stay in their homes as long as possible. Even if only five people were enabled to enter care homes a year later, the foundation’s executive director Jürg Weibel recently told the German magazine Der Spiegel, the investment would have already recouped itself. “The reality is that grown-up kids live in other areas,” Weibel said. “Also, many seniors are consciously looking for a new purpose.”

The time banks in both Sebastopol and St. Gallen have more offerings than demand. In a way, they have too much time in the bank, not least because seniors are looking to get help later in life.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

“Seniors have a lot to offer,” Gill believes. While he points to his white hair as “pretty representative of the age of our time bank members,” some universities and schools have established time banks specifically for students and teachers at their institutions.

The idea of time as a bankable currency goes back to a Japanese seamstress and activist, Teruko Mizushima, who traded her sewing skills for fresh vegetables during the Pacific War in the early 1940s. In 1973, she started the first “Volunteer Labour Bank” that soon included thousands of members.

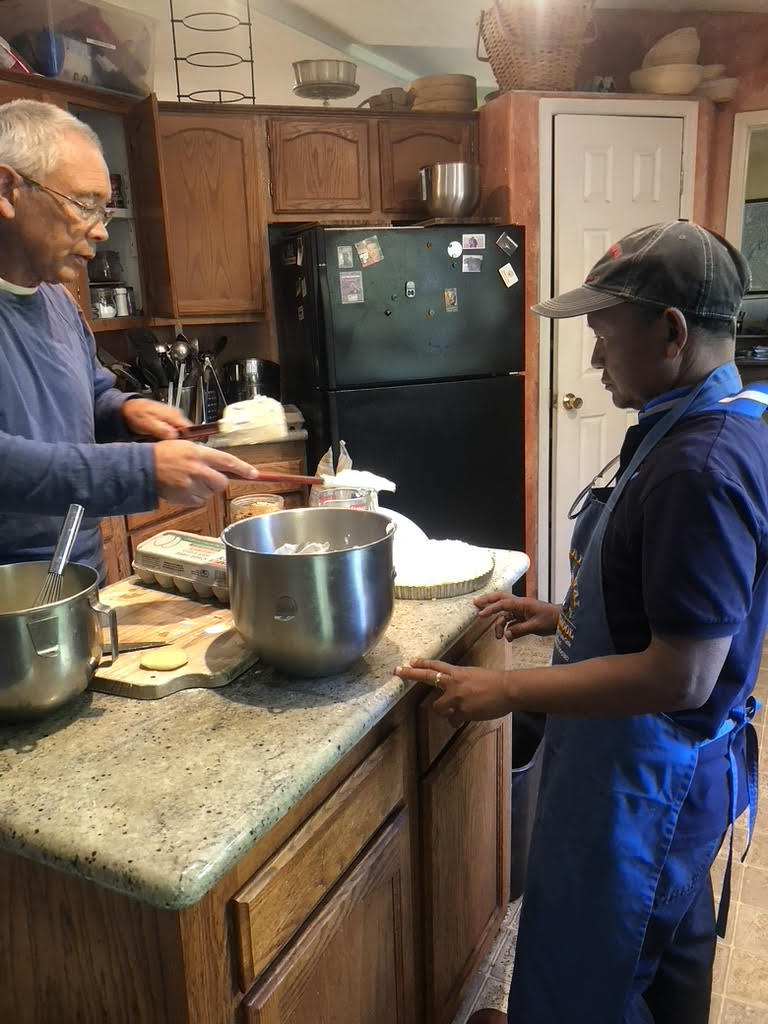

Tong Ginn (left) teaches Jesuda “Wee” Simla how to make croissants. Credit Michael D. Fels / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Tong Ginn (left) teaches Jesuda “Wee” Simla how to make croissants. Credit Michael D. Fels / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

In the US, the civil rights lawyer Edgar Cahn, who worked as a speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy and executive assistant to Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver, rediscovered the idea of time banks as allies to fight poverty in the early 1960s, when money for social programs had dried up. He later coined the term “Time Dollars” and trademarked “Time Bank.” In 1995, he founded the nonprofit Krista Wyatt now works for as a hub of resources, first under the name “Time Dollar Institute.” “When he was bedridden in a hospital after a severe heart attack, he felt ‘useless,’ and saw time banks as a way for everyone to contribute to the community, no matter their age or qualifications,” Wyatt explains.

Cahn formulated five core principles that guide time banks to this day: First, everyone has something to contribute. Second, valuing volunteering as “work.” Third, reciprocity or a “pay-it-forward” ethos. Fourth, community building, and fifth, mutual accountability and respect.

“What captured me is that people are doing things out of their own good heart,” Wyatt says. “Many years ago, a woman got really upset because, as she said to Edgar Cahn, ‘I have nothing to give.’ Edgar Cahn listened and finally responded, ‘You have love to give.’ And the whole room just went silent.”

Every hour of service is valued the same, no matter how much skill and expertise a task takes, whether it’s an hour keeping someone company, helping them file their taxes or repair a roof. Through a simple online platform, every member can offer and request services and then register the hours they served or received. Especially during and since the Covid pandemic, the bank has also been an antidote to the epidemic of loneliness. For instance, the Sebastopol time bank regularly hosts in-person events and meetings.

Lathrup Village, Michigan time bank members doing yard work together. Credit: Michigan Municipal League

Lathrup Village, Michigan time bank members doing yard work together. Credit: Michigan Municipal League

“We do events where everybody brings a list of five things they need to get done,” Wyatt gives an example. “You wouldn’t believe how many things get crossed off these lists in a room full of people who are willing to help.”

Wyatt came to TimeBanks after supporting cancer survivors. She’d read Cahn’s 2000 book, No More Throw-Away People, and was looking for a way to give back. “There are people like me who like to work on the computer rather than cleaning my garage,” Wyatt says, “and there are people who’d rather clean a garage than be stuck behind a computer. Everybody can be part of the time bank community. It’s as simple as that.”

In a way, time banks are the 2.0 version of what used to happen organically in small communities: Neighbors and colleagues would help each other out. “Now we simply do it with the help of a computer,” Gill says. “Or you may just pick up the phone and call another member directly rather than post a request online. It helps to get to know the various members.”

Artist Elizabeth “Liz” Newton with David Gill’s repaired and mosaic toilet tank cover. Credit: David Gill / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Artist Elizabeth “Liz” Newton with David Gill’s repaired and mosaic toilet tank cover. Credit: David Gill / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

While the core principles are simple, both Wyatt and Gill acknowledge that implementing and managing the time bank well is a complex task. They both spent countless hours trying out different software programs before settling on a program that works well for them.

Wyatt dreams of connecting the various time banks internationally so that someone in, say, San Francisco, could learn French with a time bank member in Paris. Or a tourist traveling in Japan could meet local time bank members there and, after her return, show other tourists around her own town.

Interpreted this way, the time credit functions as an alternative currency. Members can also donate their services to community members in need and the community without banking a credit for themselves.

For instance, in Sebastopol, artist Ellie Kilner completed a giant sculpture at the Sebastopol Senior Arts Center and other art projects with the support of fellow time bank members.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Gill’s favorite exchange, so far, also has to do with art and with a broken toilet cover. Because the toilet was an ancient model, it was impossible to find a replacement. He posted a request for help on the time bank’s online platform, and a local mosaic artist not only glued the broken pieces together but turned it into a colorful piece of art. “Now it’s a conversation piece!” Gill raves. He says he plans to request more work from this artist, Elizabeth Newton.

He is clearly passionate about his role in facilitating the time bank and everything that time banks can provide: “I don’t think we can ever have too many friends or too much community.”

The post Banking the Most Valuable Currency: Time appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

A Community-Driven Path to Replenishing Groundwater in a Parched Region

A lone tractor trundles along a bumpy road in Banda, one of the most drought-prone districts in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Up until a few years ago, soil here would dry and crack into fissures deep enough for unwary cows to fall in. Today, as we drive toward a little village called Jakhni, we see rice paddies usually found only in much wetter climes. A large pond comes into view, and behind it, Jakhni.

Thanks to a revival of old farming practices and growing community involvement in all matters relating to water, this village is now known in India as a model jalgram, or water village.

Jakhni is a settlement of barely 1,600 people, mostly farmers. Its stony, hilly terrain is typical of Bundelkhand, an arid region spread across parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. This region receives between 800 and 1,300 millimeters of rainfall annually, but locals quip that like their children, who all tend to migrate for better opportunities, the rainwater runs off too. The rocks that lie beneath the region are not very porous, and there are relatively few aquifers (layers of underground water). As a result, most of the rainwater flows away from the region instead of being locally absorbed.

“Growing up, the water scarcity we experienced in Jakhni was scary,” Uma Shankar Pandey, a 52-year-old resident of Jakhni, recounts.

The post A Community-Driven Path to Replenishing Groundwater in a Parched Region appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

How an Interactive Database Brought Earthquake Relief to Off-the-Map Villages

Late one night in September, a shallow earthquake struck the Atlas Mountains in western Morocco. The US Geological Survey said the quake had a magnitude of 6.8 with an epicenter some 72 kilometers (45 miles) southwest of Marrakech, the North African country’s fourth-largest city. When it struck across six provinces that night, the earthquake affected an area larger than Switzerland.

The worst-hit locations were literally off the map — rural mountainous villages unfamiliar to most Moroccan citizens, let alone relief workers from foreign countries. Within hours, humanitarian aid organizations, both local and international, shifted into high gear. But the caravans, carrying basic necessities and journalists eager to tell the story, faced a hurdle: finding out where to go and how to get there.

“The post-earthquake crisis reminded me of the early days of Coronavirus, with immense confusion and absence of crucial information,” says Moroccan topographer Nabil Boutrik. “It was in 2020 that I had built my first online database to publish accurate information about the number of fatalities and infections, and to counter rumors and misinformation infesting social media platforms. Right after the earthquake, I felt the need for another database to make important information available.”

The earthquake, which was the strongest to hit the country in 60 years, killed over 2,900 people, injured about 3,000 others and left many more homeless. According to Moroccan local authorities, 2,930 villages — one-third of the villages in the High Atlas Mountains region — were either completely or partially destroyed.

Earthquake damage in a village in Ouarzazate. Credit: Abdou Faiz / Shutterstock

Earthquake damage in a village in Ouarzazate. Credit: Abdou Faiz / Shutterstock

Despite the wide-scale devastation, the Moroccan government was adamant that relief efforts be led by local workers. In an attempt to avoid geopolitical conflict and make sure that donations were used efficiently, Morocco made the controversial decision to only accept a fraction of the international aid offered. Seisme Maroc Data, the online database Boutrik created for the difficult-to-access regions, contributed to streamlining efforts and resources.

“I decided to build a bilingual [Arabic-French] interactive online database providing information about and geo-mapping the disaster-stricken areas within a 50-kilometer radius,” says Boutrik.

Within days, the database was live, and over the following weeks, it compiled information on 123 regions, including hundreds of villages as well as 54 relief organizations, providing users with updated information on road conditions and other details crucial for coordinating relief and rescue missions.

Connecting the dots

Like everyone else, Boutrik was shocked at the destruction that befell his country in a matter of seconds and the horrifying loss of lives.

“I feared for my in-laws who live in Aghadir, near the epicenter,” the 39-year-old says.

Hailing from the coastal city of Nador, the provincial capital of the northeastern Rif region of Morocco, Boutrik is no stranger to temblors: his city lies 125 kilometers south of Al Hoceima, the site of a 6.3 magnitude earthquake that claimed over 600 lives and left some 15,000 people homeless in 2004.

So with his deep knowledge of the topography of the quake-hit mountain areas, and familiarity with the state of panic such natural disasters create, Boutrik was compelled to act in the most effective way he could.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

With the help of his collaborator Yassine Chamkh, a 23-year-old computer engineering student, who was responsible for the technical aspects of the initiative, he used topographic maps and high-resolution satellite imagery to pinpoint the affected communities and small villages.

He then used this data to build the easy-to-navigate interface, consisting of several spreadsheets and an interactive Google map. The first sheet includes the names and whereabouts of all the afflicted areas and villages, a contact person in each location, their telephone numbers, and details about the survivors such as the number of children and number of people injured.

The second sheet is a table of requests, listing the names and contact information of relief organizations, the area they serve and the type of assistance required. Users only need to fill out a simple online form to add a new village and their specific assistance request. The site administrators then add the information to the two regularly-updated spreadsheets.

The platform helped organizations like the Smile Association meet each community’s individual needs. Courtesy of the Smile Association

The platform helped organizations like the Smile Association meet each community’s individual needs. Courtesy of the Smile Association

The site has had over one million visitors to date, according to Boutrik.

Since 88.1 percent of Morocco’s population has internet access, including via mobile phone, the platform was adopted quickly, even in remote regions.

The right help

The continuous updates to the database were instrumental to its success, according to those who used it.

Omar El-Malouli is a resident of Zawyat Al-Farfar district, located in Ida Ougoummad village in the Taroudant region, which reported 980 deaths. All 300 residents of El-Malouli’s village survived the earthquake, which was not the case in neighboring villages. But all 70 homes were destroyed.

But El-Malouli says the platform made a difference. “The village was in dire need of basic necessities like tents, food and blankets. The platform helped make sure that our exact needs were met,” he explains.

Sofia Ait M’barek, the president of the Marrakech-based Smile Association, says that although her organization was active in the region prior to the disaster, the platform helped increase its efficiency.

“After distributing aid to some of the affected villages in the Al Hoceima region, we registered on the platform to avoid redundancy with other charitable organizations,” says M’barek.

Soon after transporting food, bedding and clothing, she realized that as the temperatures dropped, there were other more pressing needs, like tents. “We communicated this through the platform to encourage other organizations to donate items we did not have,” she says.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

About 80 kilometers from Marrakech, in the village of Tolkin, which was totally destroyed, survivor Hassan recounts a similar situation.

“I saw on the platform that a charitable organization was about to deliver a large quantity of milk to my village, but what we needed were blankets. I contacted them through the platform, so they brought us the blankets and sent the milk to another place where it was more needed,” he says.

The platform’s efficiency also helped reduce waste. “It gave donors information about the exact needs of each village, so the surplus would be diverted to other areas in dire need,” Boutrik explains.

A key resource

According to Anass Aktaou, who covered the earthquake for local news outlet Febrayer, charitable organizations were “the ones who benefitted the most from this platform, as they were able to precisely identify the locations and needs of each village.”

“Initiatives like this one address one of the toughest challenges faced by rescuers and volunteers, that is, making information readily available and facilitating cooperation between various entities,” says Younes Ezzouhir, a Moroccan journalist with local news site al3omk.com.

“Rugged and unfamiliar terrain, known only to the local population, was a challenge for journalists, rescuers and volunteers. The platform helped save lives as it sped up the evacuation, rescue and shelter operations,” Ezzouhir adds.

A village in the Atlas Mountains as it appeared before the earthquake. Credit: A.Pushkin / Shutterstock

A village in the Atlas Mountains as it appeared before the earthquake. Credit: A.Pushkin / Shutterstock

According to a member of the Moroccan civilian defense in Al Houze region, where 1,680 people were killed, the initiative helped reduce the number of vehicles carrying aid to the villages, hence speeding up the delivery and streamlining donations.

“The roads were so congested, and rescue teams struggled to reach some of the villages,” he says. (He asked to remain anonymous, as he was not authorized to speak to the press.)

A Spanish relief worker in Amizmiz, where international rescue teams from Spain, Britain and Qatar were stationed, agreed that the platform had a huge impact on the speed of operations.

“This kind of work is essential during natural disasters, not only in Morocco but worldwide,” he said. “When we first arrived, the narrow unpaved roads were packed with cars eager to help from all over the country. This individual initiative saved time and helped us rescue more people.”

According to Boutrik, right after the earthquake struck, a charity called Nt3awnou (“we collaborate” in Arabic) used its own online platform to coordinate the delivery of essential needs between NGOs and earthquake victims. But the effort was too localized and did not help the worst-hit remote villages. “The platform I built expanded this idea to cover a wider region and to geolocate the unknown villages,” says Boutrik. “But anyone on earth can replicate this online database if they have enough knowledge of the topography of the region they wish to cover and if they have the necessary technical skills.”

Two months after the quake, traffic on the platform has slowed, but it will remain available as a reference, says Chamkh: “Even though the emergency response is over and the platform will no longer be updated, the site will remain live and the data will always be available for the public as documentation.”

The article was published in collaboration with Egab.

The post How an Interactive Database Brought Earthquake Relief to Off-the-Map Villages appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.