Sunday, 3 June 2018 - 1:39pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- How Colonies Can Liberate Themselves by Taxing Real Estate — Polly Cleveland in the D&S Blog:

A reform government can heavily tax the value of real estate, possibly with exemptions for small resident property owners. Better yet, and much easier to implement, tax only the land component of real estate. Such a tax would force absentee owners to send euros or dollars back to the colonies. The government could then begin to provide services and repair infrastructure. But why tax real estate? Why not tax income or imports? Because absentees and foreign based corporations can easily avoid income taxes by funny accounting. Taxes on most imports are regressive and a drain on the economy. The real money is in real estate.

- America is one of the Few Cultures with Insults for Smart People — Ted Rall:

Languages tend to evolve to reflect the cultural and practical priorities of the societies that speak them. This linguistic truism came to mind recently when, as part of research for one of my cartoons, I turned to Google Translate in search of a French translation for the English word “geek.” There wasn’t one. Nor in Spanish. All the Romance languages came up short; Google suggested “disadattato” in Italian, but that’s different — it means “misfit,” or “a person who is poorly adapted to a situation or environment.” A “geek” — “a person often of an intellectual bent who is disliked,” according to Merriam-Webster — is decidedly distinct from a misfit. You can tell a lot about a culture from its language. I had stumbled across a revealing peculiarity about American English: we insult people for being intelligent.

- How Bill Cosby, Obama and Mega-preachers Sold Economic Snake Oil to Black America — Lester K. Spence interviewed by Lynn Parramore at INET:

I begin the book by juxtaposing Nat Adderley and Oscar Brown’s “Work Song” that’s about a certain type of labor in the 1960s against Ace Hood’s, “Hustle Hard.” He does more than just describe a condition in which he’s consistently having to work to make ends meet for himself and his family. The video features Ace Hood in a regular East Coast neighborhood, and all around him, people engage in different hustles to get by. The seasons change, and although the things that people sell change, like in the summer they’re hustling water and in the winter they’re hustling coats and gloves, the hustle itself doesn’t change. He doesn’t give a critique of that situation, but actually makes a normative argument for it, suggesting that it is a good thing. If you want to work in the world, this is what you’re supposed to do. If you don’t do it, your value as a human being is significantly reduced.

- Education – a faux crisis, an erroneous ‘solution’ and capital wins again — Bill Mitchell:

One of the ways in which the neoliberal era has entrenched itself and, in this case, will perpetuate its negative legacy for years to come is to infiltrate the educational system. This has occurred in various ways over the decades as the corporate sector has sought to have more influence over what is taught and researched in universities. The benefits of this influence to capital are obvious. They create a stream of compliant recruits who have learned to jump through hoops to get delayed rewards. In the period after full employment was abandoned firms also realised they no longer had to offer training to their staff in the same way they did when vacancies outstripped available workers. As a result they have increasingly sought to impose their ‘job specific’ training requirements onto universities, who under pressure from government funding constraints have, erroneously, seen this as a way to stay afloat. So traditional liberal arts programs have come under attack – they don’t have a ‘product’ to sell – as the market paradigm has become increasingly entrenched. There has also been an attack on ‘basic’ research as the corporate sector demands universities innovate more. That is code for doing the privatising public research to advance profit. But capital still can see more rewards coming if they can further dictate curriculum and research agendas. So how to proceed. Invent a crisis. If you can claim that universities will become irrelevant in the next decade unless they do what capital desires of them then the policy debate becomes further skewed away from where it should be. That ‘crisis invention’ happened this week in Australia.

- Google and Facebook won’t rule the world – if we don’t buy their fantasies about big data — Alexander Taylor in the Conversation:

Claims that big data and targeting will determine the next US president, and fears that data analytics allow politicians to exploit our psychological vulnerabilities have at their root a deterministic view, which sees social media users as completely passive and open to manipulation. But this view ignores how users actively process information, with differing perspectives, interests and forms of engagement. Paradoxically, while the data-driven advertising industry increasingly recognises the diversity of internet users’ psychological profiles and behavioural patterns, it seems to assume that they are all equally suggestible when it comes to social media advertising.

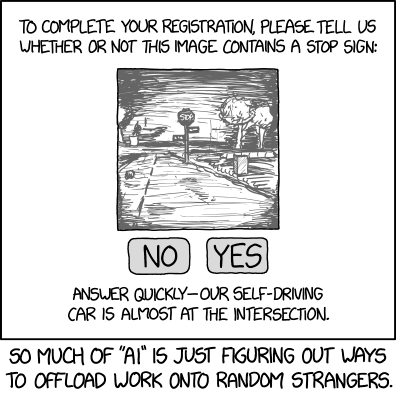

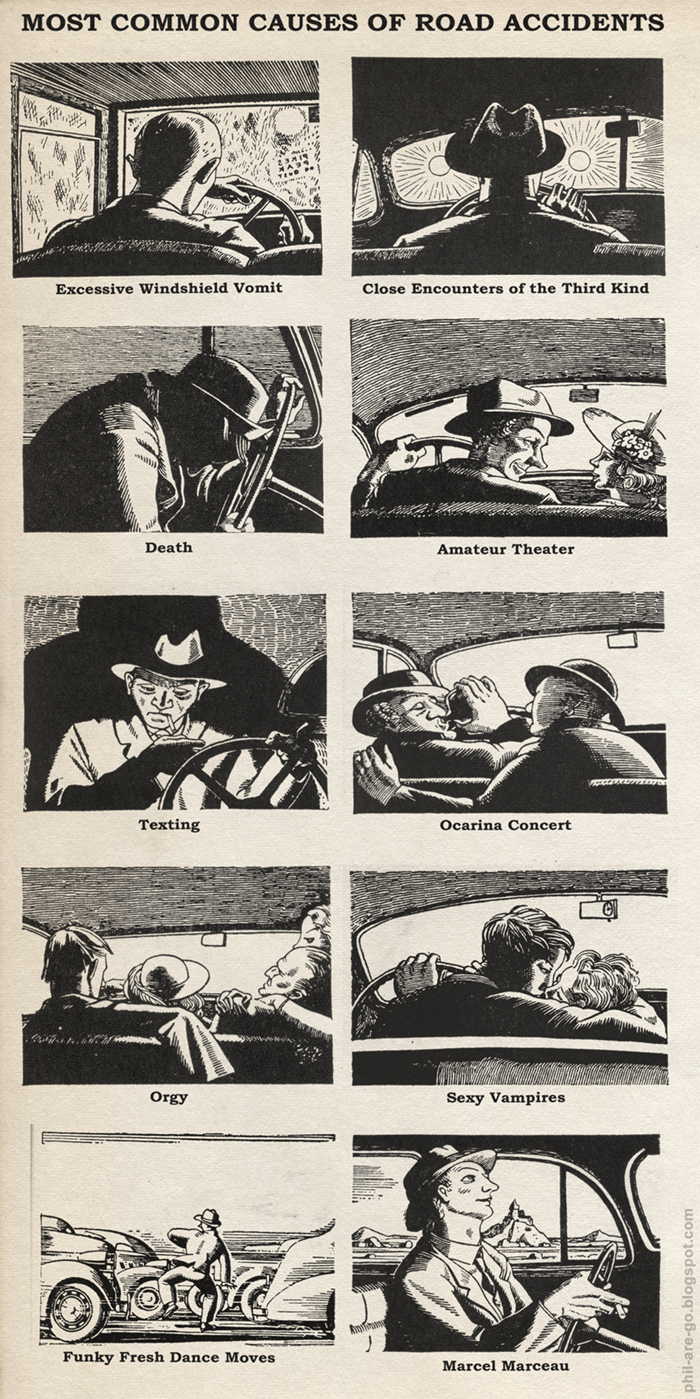

- Your Automobile and You - Road accident causes — Phil Are Go!:

- Are You in a BS Job? In Academe, You’re Hardly Alone — David Graeber in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

Support staff no longer mainly exist to support the faculty. In fact, not only are many of these newly created jobs in academic administration classic bullshit jobs, but it is the proliferation of these pointless jobs that is responsible for the bullshitization of real work — real work, here, defined not only as teaching and scholarship but also as actually useful administrative work in support of either. What’s more, it seems to me this is a direct effect of the death of the university, at least in its original medieval conception as a guild of self-organized scholars. Gayatri Spivak, a literary critic and university professor at Columbia, has observed that, in her student days, when people spoke of "the university," it was assumed they were referring to the faculty. Nowadays it’s assumed they are referring to the administration. And this administration is increasingly modeling itself on corporate management.

- Donald Trump has shown himself to be the American version of Gaddafi in his behaviour towards Iran and the nuclear deal — Robert Fisk:

Gaddafi’s handshake was legendary – so was his kiss from Tony Blair, who was as obsequious to Gaddafi in Libya as Theresa May was to Trump in Washington. Much good did it do Blair or May. Gaddafi ran his business dealings through his family – now there’s a thought – and even maintained good relations with Russia. His speeches were interminable – he liked the sound of his own voice – and although he constantly lied, his audience was forced to listen and to fear his wrath. Above all, Gaddafi was completely divorced from reality. If he lied, he believed his own lies. He believed that he kept his promises. He believed in the world he wanted to believe in, even if this was non-existent. His Great Man Made River Project was supposed to Make Libya Great Again.

- The Philip Cross Affair — Craig Murray:

133,612 edits to Wikpedia have been made in the name of “Philip Cross” over 14 years. That’s over 30 edits per day, seven days a week. And I do not use that figuratively: Wikipedia edits are timed, and if you plot them, the timecard for “Philip Cross’s” Wikipedia activity is astonishing is astonishing if it is one individual […] There are three options here. “Philip Cross” is either a very strange person indeed, or is a false persona disguising a paid operation to control wikipedia content, or is a real front person for such an operation in his name. Why does this – to take the official explanation – sad obsessive no friends nutter, matter? Because the purpose of the “Philip Cross” operation is systematically to attack and undermine the reputations of those who are prominent in challenging the dominant corporate and state media narrative. particularly in foreign affairs. “Philip Cross” also systematically seeks to burnish the reputations of mainstream media journalists and other figures who are particularly prominent in pushing neo-con propaganda and in promoting the interests of Israel.

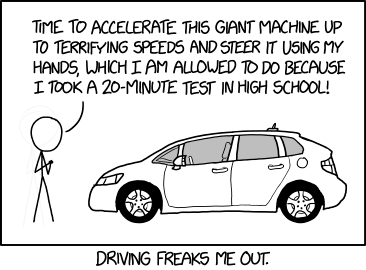

- Driving Cars — xkcd:

Sunday, 27 May 2018 - 3:49pm

This week, it's been increasingly obvious that I'm trying to catch up by counter-productively just bookmarking all the substantive articles:

- ‘I believe because it is absurd’: Christianity’s first meme — Peter Harrison in Aeon:

Scholars of early Christianity have long known that Tertullian never wrote those words. What he originally said and meant poses intriguing questions, but equally interesting is the story of how the invented expression came to be attributed to him in the first place, what its invention tells us about changing conceptions of ‘faith’, and why, in spite of attempts to correct the record, it stubbornly persists as an irradicable meme about the irrationality of religious commitment. On the face of it, being committed to something because it is absurd is an unpromising foundation for a belief system. It should not come as a complete surprise, then, that Tertullian did not advocate this principle. He did, however, make this observation, with specific reference to the death and resurrection of Christ: ‘it is entirely credible, because it is unfitting … it is certain, because it is impossible’ (For Latinists out there: prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est … certum est, quia impossibile). This might seem to be within striking distance of the fideistic phrase commonly attributed to him. Puzzlingly, though, even this original formulation does not fit with Tertullian’s generally positive view of reason and rational justification. Elsewhere, he insists that Christians ‘should believe nothing but that nothing should be rashly believed’. For Tertullian, God is ‘author of Reason’, the natural order of the world is ‘ordained by reason’, and everything is to be ‘understood by reason’.

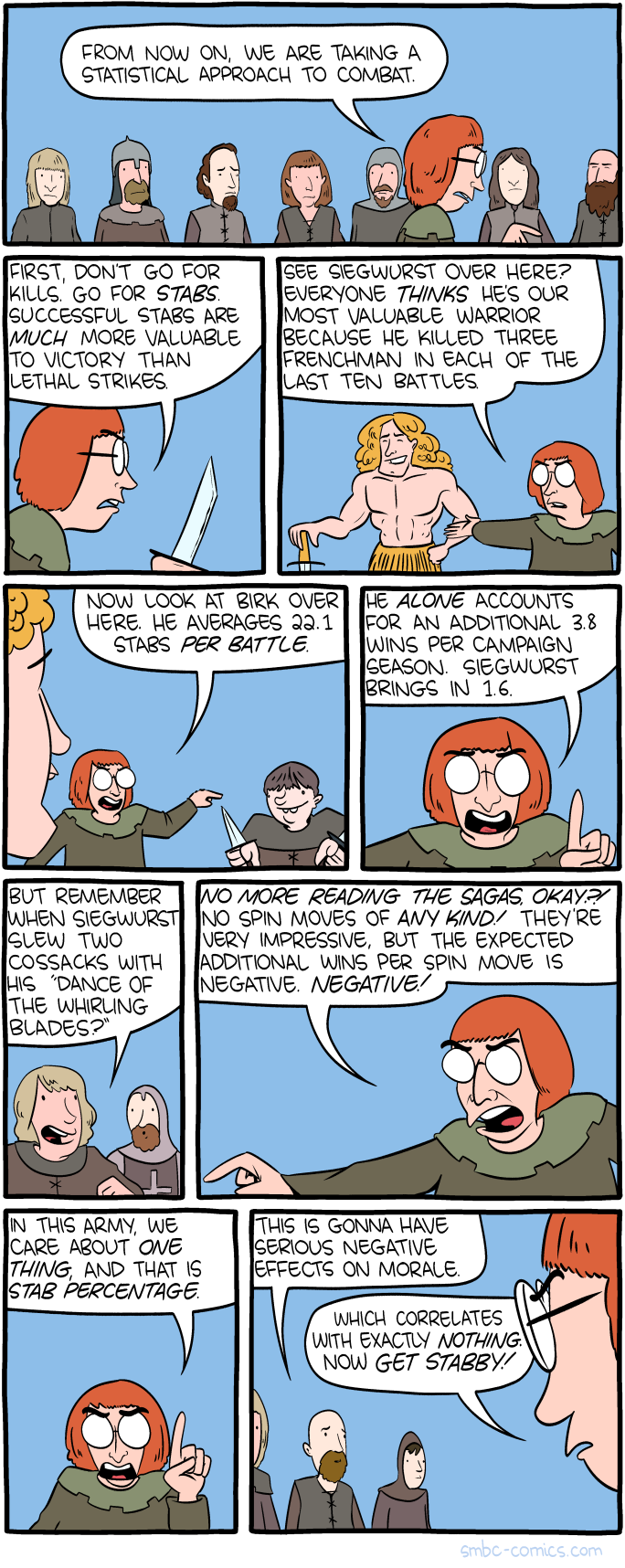

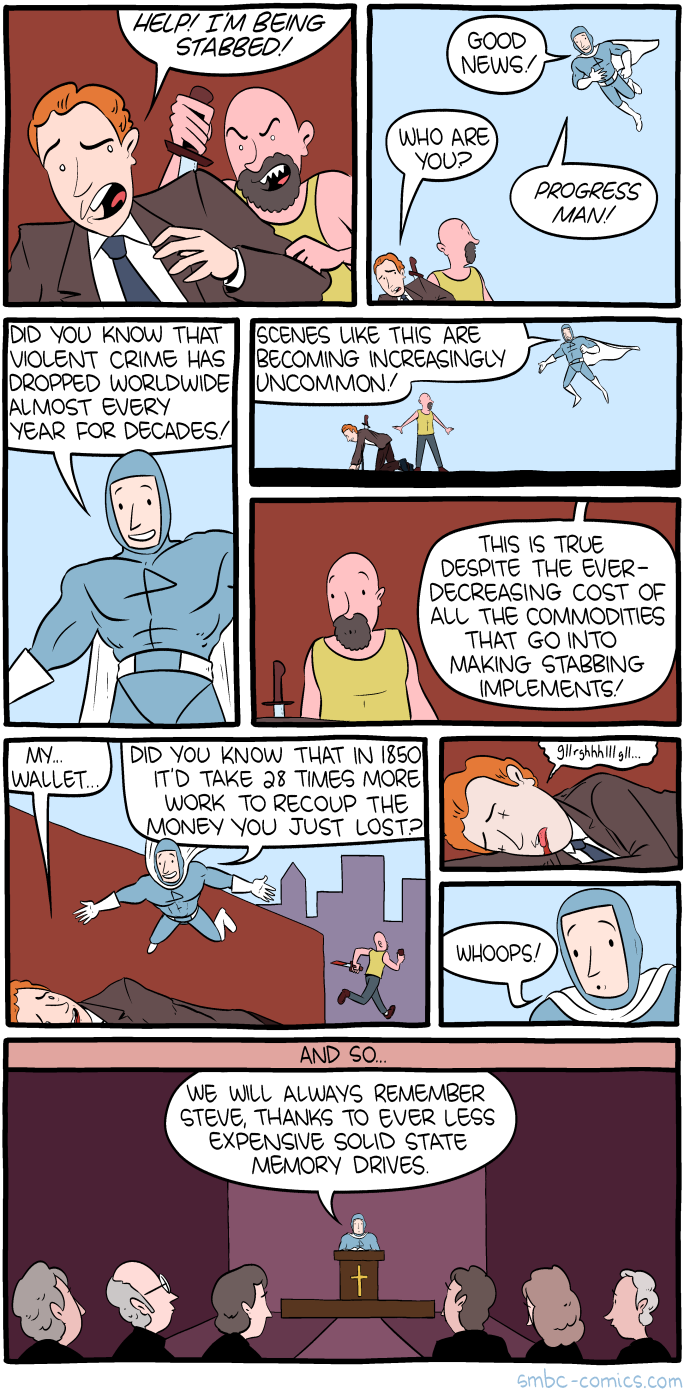

- Moneybattle — Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal:

- The Power of Trump’s Positive Thinking — Michael Kruse, at POLITICO who, ironically, also favour all-caps:

The reality is that Trump is in a rut. His legislative agenda is floundering. His approval ratings are historically low. He’s raging privately while engaging in noisy, internecine squabbles. He’s increasingly isolated. And yet his fact-flouting declarations of positivity continue unabated. For Trump, though, these statements are not issues of right or wrong or true or false. They are something much more elemental. They are a direct result of the closest thing the stubborn, ideologically malleable celebrity businessman turned most powerful person on the planet has ever had to a devout religious faith. This is not his mother’s flinty Scottish Presbyterianism but Norman Vincent Peale’s “power of positive thinking,” the utterly American belief in self above all else and the conviction that thoughts can be causative, that basic assertion can lead to actual achievement.

- Come on, Floppy Sue — Phil Are Go!:

- BRONZE AGE REDUX: On Debt, Clean Slates And What The Ancients Have To Teach Us — Harold Crooks interviews Michael Hudson for A Gathering of the Tribes:

What I realized is that when Luke 4 reports the first speech of Jesus, when he goes to the temple and gives his first sermon, he unrolls the Scroll of Isaiah, and says he has come to proclaim the Jubilee year …. The word he used, and that Isaiah used, the deror, was this Babylonian, Near Eastern long tradition that was common throughout the whole Near East. Now most of the Biblical translations miss this point. They were translated in the 17th and 16th century, when people didn't know cuneiform, so they had no idea what these words meant and what the background of the Jubilee year was. And 50 years ago, there was almost a universal idea that the Jubilee year was something idealistic, utopian, and could never actually be applied in practice. But we know that in Babylonia, Sumer and Near Eastern regions, it was applied in practice. Not only do we have the royal proclamations, we have the lawsuits by debtors saying "This creditor didn't forgive me the debt," and the judgments for that. Each member of Hammurabi's dynasty after him ending up with this great grandson Ammi-Saduqa had more and more detailed anderarum acts, debt cancellations, to close all the loopholes that creditors tried to resort to.

- #1391; In which a Visit proves Vicious — Wondermark, by David Malki !:

Sunday, 20 May 2018 - 11:51am

This week, I have been mostly reading comics, because reality has been very disappointing:

- How long after this week's Gaza massacre are we going to continue pretending that the Palestinians are non-people? — Robert Fisk, the Independent:

Monstrous. Frightful. Wicked. It’s strange how the words just run out in the Middle East today. Sixty Palestinians dead. In one day. Two-thousand-four-hundred wounded, more than half by live fire. In one day. The figures are an outrage, a turning away from morality, a disgrace for any army to create. And we are supposed to believe that the Israeli army is one of “purity of arms”? And we have to ask another question. If it’s 60 Palestinians dead in a day this week, what if it’s 600 next week? Or 6,000 next month? Israel’s bleak excuses – and America’s crude response – raise this very question. If we can now accept a massacre on this scale, how far can our immune system go in the days and weeks and months to come?

- Excelsior! — Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal:

- A Travesty of Protectionism — Michael Hudson:

The idea of industrial protectionism, from British free trade in the 19th century to U.S. trade strategy in the 20th century, was to obtain raw materials in the cheapest places – by making other countries compete to supply them – and protect your high-technology manufactures where the major capital investment, profits and monopoly rents are. Trump is doing the reverse: He’s increasing the cost of steel and aluminum raw materials inputs. This will squeeze the profits of industrial companies using steel and aluminum – without protecting their markets.

- Not Available — xkcd:

- The Victorians portrayed paedophiles as strangers – and the myth persists today — Ailise Bulfin in the Conversation:

The Victorians portrayed paedophiles as scary strangers and social outsiders. By portraying them in this way, it was possible to avoid the unthinkable reality that children could be abused in respectable middle-class homes. This myth of the stranger paedophile is still persistent today. And even though the evidence shows that most child sexual abuse is perpetrated by close family members, the stranger myth continues to distract our attention from the most common type of abuse.

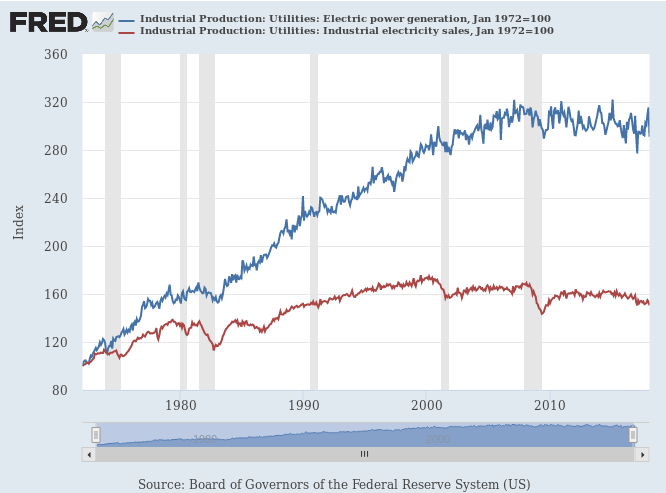

- There’s electricity in the air! But it’s not for sale — The FRED® Blog:

The graph above shows that electricity production in the United States has steadily grown; and, about 10 years ago, it plateaued. Electricity sales, however, have barely increased in the past decades. What’s happening? The divergence between the two measures is, to a large extent, due to more and more electricity production never hitting the market. Many firms and even households produce their own energy for their own use. This could be energy extraction from byproducts of production such as biogas or burning waste or running one’s own wind or solar farm. The recent flattening of electricity production reflects the fact that electricity demand is not increasing as it has in the past, thanks to improved energy efficiency all around.

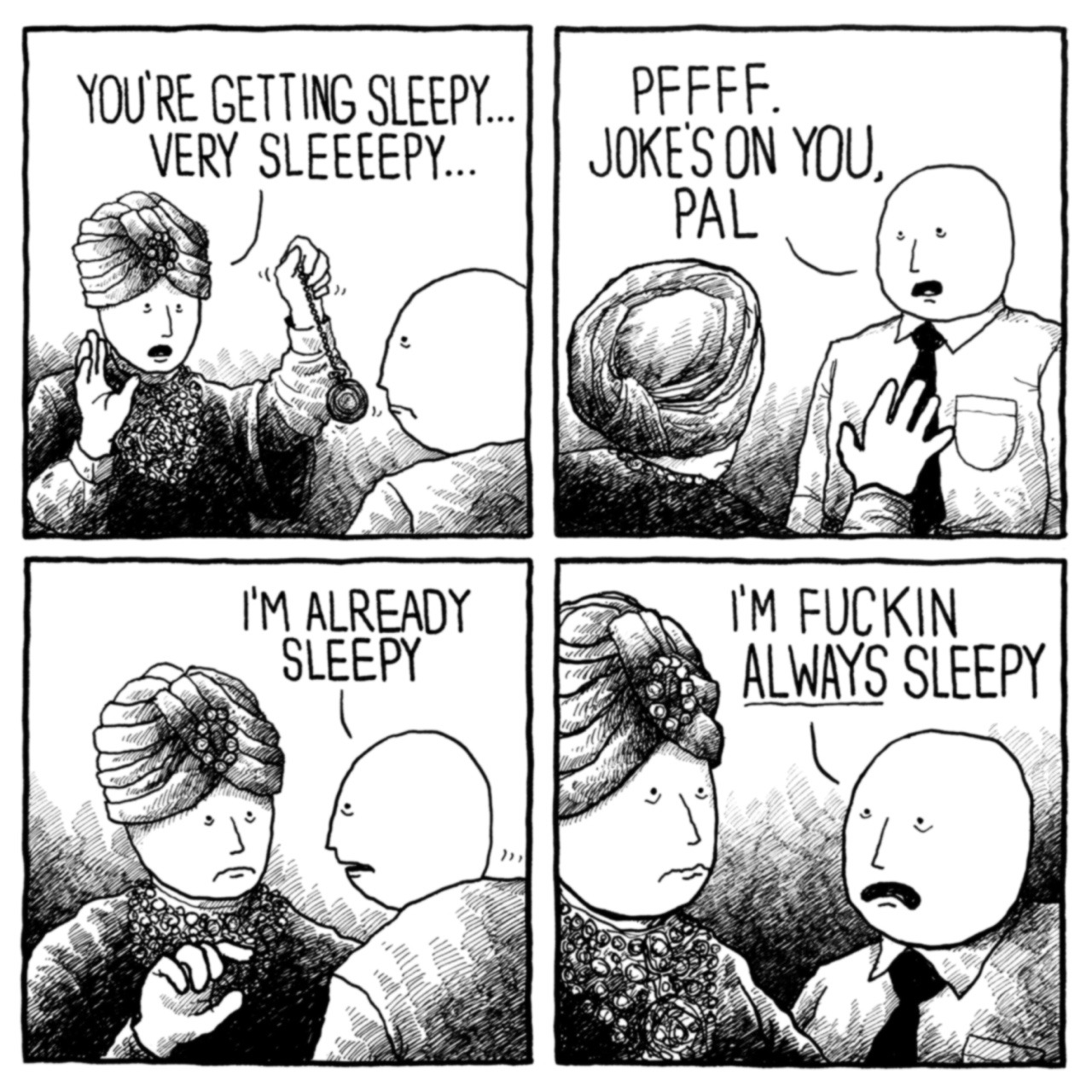

- I Win — Jake Likes Onions:

Sunday, 13 May 2018 - 2:52pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The blight of the visitor economy — Bill Mitchell:

One of the large funded projects that I have been involved in over the last few years concerns regional equity (in part). Our planning involves the completion of a new book (to be published sometime 2019) on the way in which regional development has become biased to the economic settlement (where jobs are created) at the expense of the social settlement (where people live). This might sound reasonable until you realise that it is another aspect of the way in which governments have abandoned their remit to ensure general prosperity, and have, instead, ‘allowed the market to work’ – which is neoliberal code for tilting the playing field in favour of corporations and global capital. One of the more recent neoliberal ruses in this context, that undermine the lived experience of local residents and boost the profits of large corporations is the concept of the ‘visitor economy’, which is the new buzzword for Tourist-led growth. Governments who claim they have run out of money are quick to hand out massive subsidies to large-scale events to promote the ‘visitor economy’. The same governments also subvert their own planning rules, encourage multi-national corporations to exploit loopholes in labour laws to cut wages and conditions, and privatise valuable public assets to ensure corporations can extract as much profit from activities as possible. Local residents’ rights are trampled in this process as corporations turn their suburbs into ‘global playgrounds’ while pocketing massive public subsidies into the bargain.

- Planes don’t flap their wings: does AI work like a brain? — Grace Lindsay in Aeon:

In 1739, Parisians flocked to see an exhibition of automata by the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson performing feats assumed impossible by machines. In addition to human-like flute and drum players, the collection contained a golden duck, standing on a pedestal, quacking and defecating. It was, in fact, a digesting duck. When offered pellets by the exhibitor, it would pick them out of his hand and consume them with a gulp. Later, it would excrete a gritty green waste from its back end, to the amazement of audience members. Vaucanson died in 1782 with his reputation as a trailblazer in artificial digestion intact. Sixty years later, the French magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin gained possession of the famous duck and set about repairing it. Taking it apart, however, he realised that the duck had no digestive tract. Rather than breaking down the food, the pellets the duck was fed went into one container, and pre-loaded green-dyed breadcrumbs came out of another.

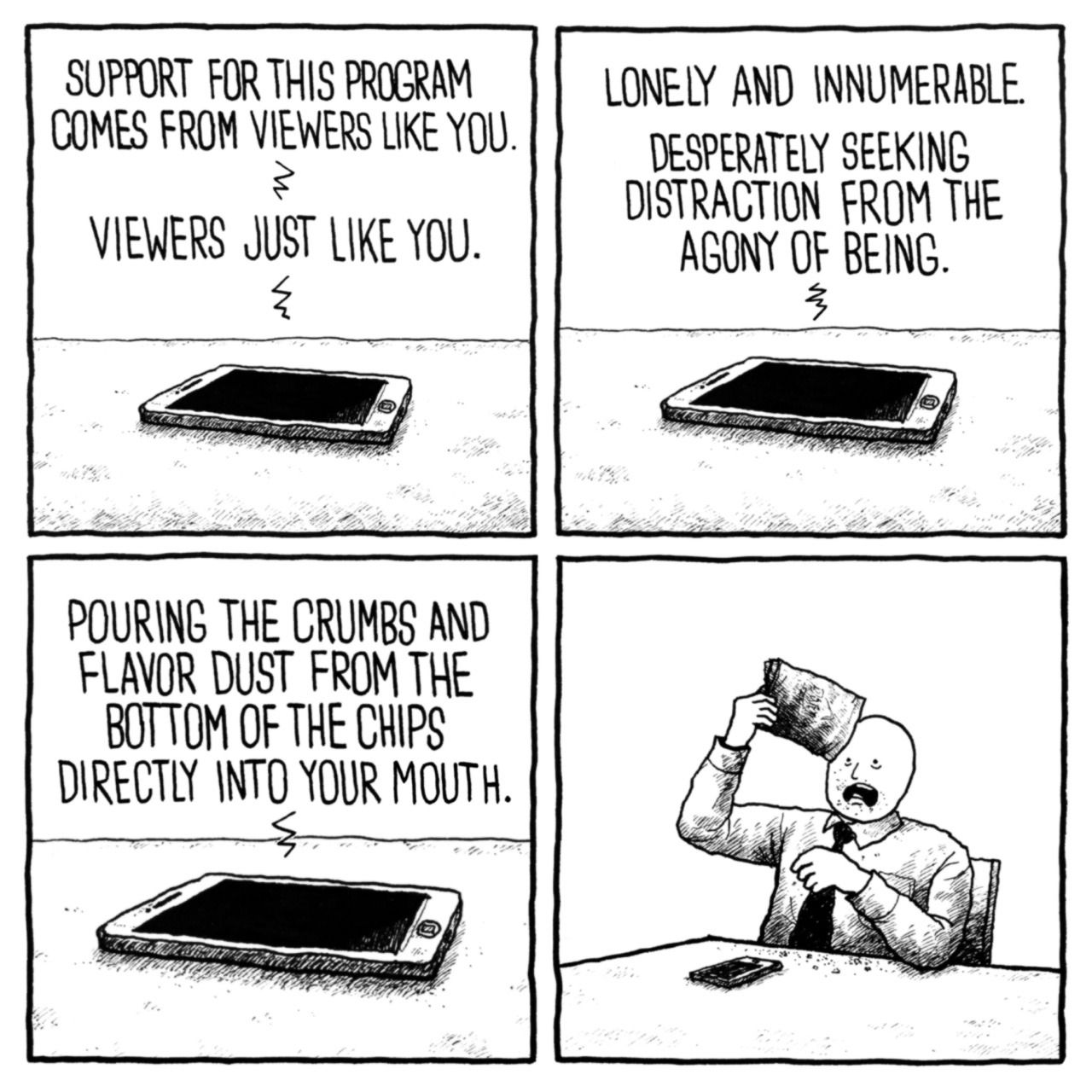

- Viewers Like You — Jake Likes Onions:

- From Whole Foods to Amazon, Invasive Technology Controlling Workers Is More Dystopian Than You Think — Thor Benson at In These Times:

In early February, media outlets reported that Amazon had received a patent for ultrasonic wristbands that could track the movement of warehouse workers’ hands during their shifts. If workers’ hands began moving in the wrong direction, the wristband would buzz, issuing an electronic corrective. If employed, this technology could easily be used to further surveil employees who already work under intense supervision. Whole Foods, which is now owned by Amazon, recently instituted a complex and punitive inventory system where employees are graded based on everything from how quickly and effectively they stock shelves to how they report theft. The system is so harsh it reportedly causes employees enough stress to bring them to tears on a regular basis.

- Buying Power: an often neglected, yet essential concept for economics — Michael Joffe at the Minskys:

In 1776, Adam Smith wrote that the degree to which a “man is rich or poor” depends mainly on the quantity of other people’s “labour which he can command, or which he can afford to purchase” (emphasis added). However, this idea of differential buying power has never been incorporated into economic theory, despite it being an obvious feature of the world we live in. The extent of a person’s disposable income and wealth gives them a corresponding degree of influence. It is like a voting system, where everybody votes for their view of what the economy should produce, but where the number of votes is very unequal. The term “power” here is best understood as meaning the degree of ability of a person or organization to bring something about. It is a causal (not e.g. a moral or political) concept. Examples of its importance are everywhere. When prices rise, some potential consumers may be excluded – a form of rationing. In pleasant locations, affluent urban dwellers buy holiday homes, crowding out the local inhabitants who do not have the buying power to compete and therefore may have to leave the area. In low-income countries, the amount of transactional sex depends on inequality (the buying power of richer men), not poverty. Any industry depends on its (potential) customers’ buying power for support: washing machine manufacture is only possible if there is a market of people who can afford their product; luxury goods such as mega-yachts exist because there are mega-rich people to buy them.

- Why Amartya Sen remains the century’s great critic of capitalism — Tim Rogan in Aeon:

Every major work on material inequality in the 21st century owes a debt to Sen. But his own writings treat material inequality as though the moral frameworks and social relationships that mediate economic exchanges matter. Famine is the nadir of material deprivation. But it seldom occurs – Sen argues – for lack of food. To understand why a people goes hungry, look not for catastrophic crop failure; look rather for malfunctions of the moral economy that moderates competing demands upon a scarce commodity. Material inequality of the most egregious kind is the problem here. But piecemeal modifications to the machinery of production and distribution will not solve it. The relationships between different members of the economy must be put right. Only then will there be enough to go around.

- Officer Friendly — This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow:

- Scientific Salami Slicing: 33 Papers from 1 Study — Neuroskeptic:

Given that scientists are judged in large part by the number of peer-reviewed papers they produce, it’s easy to understand the temptation to engage in salami publication. It’s officialy discouraged, but it’s still very common to see researchers writing perhaps 3 or 4 papers based on a single project that could, realistically, have been one big paper. But I’ve just come across a salami that’s been sliced up so thinly that it’s just absurd. The journal Archives of Iranian Medicine just published a set of 33 papers about one study.

Sunday, 6 May 2018 - 6:46pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Australian universities must eschew narrow fixation on jobs — Lee Duffield in Independent Australia:

If you accept that education is education at any level and might be about more than the immediate jobs drive, consider also liberal thought — which works around cultivation and self-cultivation of the individual, free person. Liberal thought supports the idea that if you have properly studied something, you have a good chance of being able to do anything. If you are well read and empowered by other deep studies, you can competently take charge of your own vocational search and become a useful thinker in society across a whole range of human activities. It is the idea that universities putting resources into best academic standards will be bound to produce good outcomes for the professions, research, society in general.

- The next cryptocurrencies — Jen Sorensen:

- Answers from the MMTers — Stephanie Kelton and Randall Wray at the New Economic Perspectives blog:

A few days ago, Jared Bernstein posed some Questions for the MMTers in order to gain a “better understanding [of our] arguments.” We appreciate his interest in our ideas and, especially, his direct appeal for clarification of our views. He raised four big questions, which our Australian counterpart, Bill Mitchell, has already answered in his own three-part series. What follows is a response from two North American MMTers.

- CES Shows That the Future Will Not Work — Yves Smith, Naked Capitalism:

A new article by Taylor Lorenz in the Daily Beast, CES Was Full of Useless Robots and Machines That Don’t Work, by virtue of doing what tech writers are never supposed to do, namely report as opposed to cheerlead, is being buried despite its importance. Lorenz went to the what is the biggest, most important consumer tech trade show in the US, and arguably the world, and found that tons of the great new gotta-have-them wares in the pipeline don’t work. As in unabashedly, obviously don’t work or are so ludicrously not fit for purpose as to be the functional equivalent of not work. This inability to even credibly fake next gen products, and worse, not even be embarrassed that they aren’t performing, is proof that the tech industry has gone past an event horizon into a state of obvious collective impotence and not one cares or even seems to regard it as unusual.

- Economist James K. Galbraith isn’t celebrating Dow 25,000 — interview by Greg Robb of MarketWatch:

The Dow is not a serious indicator of the condition of the economy. What we’ve had is a long but fairly slow expansion and a lot of reduction in the effective size of the labor force. Employment ratios have risen a little, but they are still way below where they were 10 or, for that matter, 20 years ago. I think there are really major changes in the structure of the economy going forward. The share of business investment has been quite low, share of construction has been very low, and that means the economy is being driven increasingly by the consumer. The consumer is dependent upon the access to debt, auto loans, consumer loans and student loans. Those things will build up over time until such time as there is a crack and households decide that they no longer wish to access the credit — at which point this phase of the expansion will end.

- #1370; The Avian Informant, Part 2 — Wondermark, by David Malki !:

Sunday, 29 April 2018 - 2:15pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Video Game “Loot Boxes” Are Like Gambling for Kids — and Lawmakers Are Circling — Zaid Jilani at the Intercept:

In mid-November, video game publisher Electronic Arts released “Star Wars Battlefront II,” a multiplayer shooter for consoles and PCs. The title is likely to be a top item on many holiday shoppers’ lists; the original “Battlefront” sold an estimated 12 million copies. But “Battlefront II,” rated for ages 13 and up, has ignited a firestorm of controversy for the particularly cynical way it pushes players to buy “loot boxes,” random collections of in-game abilities that remain a mystery until purchased. Experts say loot boxes prey on addictive impulses that can be particularly difficult for children and other young people to control. Lawmakers, meanwhile, are considering regulating loot boxes as a form of gambling.

- Bizarro! — by Dan Piraro:

- The Illusionist — David Bentley Hart in the New Atlantis reads Dan Dennett's latest, so that we don't have to:

The idea that the mind is software is a fairly popular delusion at the moment, but that hardly excuses a putatively serious philosopher for perpetuating it — though admittedly Dennett does so in a distinctive way. Usually, when confronted by the computational model of mind, it is enough to point out that what minds do is precisely everything that computers do not do, and therein lies much of a computer’s usefulness. Really, it would be no less apt to describe the mind as a kind of abacus. In the physical functions of a computer, there is neither a semantics nor a syntax of meaning. There is nothing resembling thought at all. There is no intentionality, or anything remotely analogous to intentionality or even to the illusion of intentionality. There is a binary system of notation that subserves a considerable number of intrinsically mindless functions. And, when computers are in operation, they are guided by the mental intentions of their programmers and users, and they provide an instrumentality by which one intending mind can transcribe meanings into traces, and another can translate those traces into meaning again. But the same is true of books when they are “in operation.” And this is why I spoke above of a “Narcissan fallacy”: computers are such wonderfully complicated and versatile abacuses that our own intentional activity, when reflected in their functions, seems at times to take on the haunting appearance of another autonomous rational intellect, just there on the other side of the screen. It is a bewitching illusion, but an illusion all the same. And this would usually suffice as an objection to any given computational model of mind. But, curiously enough, in Dennett’s case it does not, because to a very large degree he would freely grant that computers only appear to be conscious agents. The perversity of his argument, notoriously, is that he believes the same to be true of us.

- Poverty eliminated — This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow:

Sunday, 22 April 2018 - 6:05pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Goldman Sachs asks in biotech research report: 'Is curing patients a sustainable business model?' — Tae Kim for CNBC:

"The potential to deliver 'one shot cures' is one of the most attractive aspects of gene therapy, genetically-engineered cell therapy and gene editing. However, such treatments offer a very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies," analyst Salveen Richter wrote in the note to clients Tuesday. "While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow."

- The citation graph is one of humankind's most important intellectual achievements — Dario Taraborelli in Boing Boing:

When researchers write, we don't just describe new findings -- we place them in context by citing the work of others. Citations trace the lineage of ideas, connecting disparate lines of scholarship into a cohesive body of knowledge, and forming the basis of how we know what we know. Today, citations are also a primary source of data. Funders and evaluation bodies use them to appraise scientific impact and decide which ideas are worth funding to support scientific progress. Because of this, data that forms the citation graph should belong to the public. The Initiative for Open Citations was created to achieve this goal.

- How the American economy conspires to keep wages down — Gabriel Winant in the Guardian:

We tend to think of employment as a market interaction: supply and demand meet to set a price, and that’s the wage you get paid. But work is much more than this. When you buy bread, there’s no other connection between you and the baker. You take your loaf and go home. But when you sell labor in the labor market, you’re entering into an ongoing power relationship. In return for your wages, you’re supposed to submit – not once but every day. It’s not just economic. Work is intrinsically political. […] The political power typically enjoyed by employers is generally experienced by workers as fear: fear of harassment, favoritism and wage theft, fear of joining a union or speaking out, fear of the consequences of injury or sickness, fear of the risks of asking for a raise, and beneath these, the fundamental workplace fear – of losing your job. The current of fear running through the workplace is one of the best ways to tell there’s something more than a market transaction happening there. But fear can go both ways. In West Virginia and Oklahoma, the irreplaceable teachers terrified Republican officials. With unemployment down, more of us are becoming irreplaceable every day. There’s leverage for workers there, but you have to be willing to scare your boss to use it.

- Against citizen science — Philip Mirowski in Aeon:

What’s really behind the rise of citizen science? There are a few distinct trends and agendas at work. One is the obvious groundswell of hostility to experts spreading throughout the Western world. It rears its head in revanchist nationalism, the anti-vaccination movement, and global-warming denial. Citizen science seems to be an attempt to co-opt and transform that hostility into something else, something useful. Governments are appealing to the megalomania of the average individual, with the (probably vain) expectation that these people will naturally temper their hostility to scientific expertise, and accept a modicum of regimentation. But it’s hard to see how citizen science can really reverse the post-truth trend. Such a hope flies in the face of sociological research indicating that greater levels of education, combined with Right-of-centre political leanings, exacerbate suspicion towards orthodox science, rather than diminishing it. Secondly, the majority of existing citizen science consists of the public donating its unpaid work and data to privately owned, online entities that subsequently digest it as ‘big data’. In other words, there’s a forest of for-profit networks and startups out there seeking to attract, harvest and capitalise upon the labour they’ve enlisted – a phenomenon that Nick Srnicek, a lecturer in digital economy at King’s College London, has dubbed ‘platform capitalism’. The insertion of such companies into the scientific process creates the risk that they will eventually exert more influence over larger research agendas than they already do.

- 81 Wrongs — TedRall:

- Booked: The Ideology of Cheap Stuff — Sarah Jaffe in Dissent Magazine:

You wouldn’t be able to have this chicken without cheap feed for the chicken. That means $1.25 billion of subsidy every year to the chicken industry, just in the United States. But also, workers don’t survive on cheap wages without cheap food. You need cheap energy to keep the henhouse going. You need cheap money to be able to bankroll the franchises. And finally, you need cheap lives. You need a regime that makes certain kinds of lives and bodies cheaper. That means, in the chicken industry, it’s women and people of color who are most likely to be injured on the line, most likely to be mangled in the chicken processing. So these are the seven cheap things embodied in the nugget: nature, money, work, care, food, energy, and lives. These things explain the trillions of chicken bones in the fossil record. The reason we wrote the book is because we want to move away from the idea that this is the Anthropocene—you know, humans being humans, in the way that boys will be boys, or sharks will be sharks. It’s not the Anthropocene—it’s the Capitalocene.

- Merit — Flea Snobbery:

Sunday, 15 April 2018 - 6:51pm

This week, erm fortnight, maybe month… Look, things aren't going so well. I just can't seem to get it together, so just read this, and could you possibly spare a tenner?:

- Reaching people on the internet — The Oatmeal:

- How Much Are Banks Exposed to Subprime? More than we Think — Wolf Richter:

One of the collapsed small lenders, Summit Financial Corp, when it filed for bankruptcy on March 23, disclosed that it owed Bank of America $77 million. This loan was secured by the auto loans Summit had extended to subprime customers, who’re now defaulting in large numbers. In the bankruptcy documents, BofA alleged that Summit had repossessed many of these cars without writing down the bad loans, thus under-reporting the losses and misrepresenting the value of the collateral (the loans). This allowed Summit to borrow more from BofA to fund more subprime loans, BofA said. Summit is just a tiny lender and doesn’t really matter. But there are a whole slew of these nonbank lenders, specializing in auto loans, revolving consumer loans, payday loans, and mortgages. Some of these nonbank lenders specialize in “deep subprime.” And some of these lenders are fairly large. Since the Financial Crisis, big banks have mostly avoided subprime lending. Instead, they’re lending to the companies that then provide financing to subprime customers. And BofA is finding out just how much risk it was taking with its loan to Summit that was secured by now defaulting auto loans that were secured by cars that, once repossessed, are worth only a fraction of the loan value when they’re sold at auction.

- Status: perpetually broke — Jake Likes Onions:

- Everything wrong with Theresa May's ridiculous assertion that we should feel proud of the Balfour Declaration — Robert Fisk, the Independent:

So let’s remember what this document actually said in 1917: “His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” The obvious lie in this single sentence – a charter for “refugeedom” if ever there was one – is that while Britain would support a Jewish “homeland”, the majority of the population (700,000 Arabs as opposed to 60,000 Jews, according to Hanan Ashrawi) are not regarded as having a “homeland” at all – but merely referred to as “existing non-Jewish communities”. They are not even called Arabs or Muslims – which most of them were – but as just “communities” which “exist”. And which of course might be persuaded one day to exist somewhere else. We can forget that Balfour and his chums admitted within months that they didn’t intend to give the Arabs any attention. They certainly didn’t get any. Within just over 30 years, Israel itself was created and the Palestinian tragedy began. And in this, Theresa May takes “pride”.

- The Murray Goulburn dilemma – co-operatives are dying out but they’re still needed — Michael Duffy in the Conversation:

Co-operatives such as Murray Goulburn have gone to private equity markets but this has diluted their co-operative structure while creating other problems such as conflict between producers and investors. This is exemplified by the current investor class action. Co-operatives also struggle with banks who are reluctant to lend as they do not understand or even distrust the co-operative structure. Some also argue that increasingly globalised free trade and excess production has depressed agricultural prices which impacts the market power of farmer co-operatives to hold out for a good price. Regulators also have an interest in transforming co-operative structures into the corporate form for ease of regulation.

Sunday, 18 March 2018 - 12:20pm

This month, I have been mostly reading:

- A former UK Chancellor attempts to save face and just becomes confused — Bill Mitchell:

The Bank of England, like other central banks, engaged in high-profile and politically damaging public commentaries about fiscal matters and other economic policies beyond their ‘legal’ remit, thus compromising the public divide between monetary policy and fiscal policy. The politicians thought they were creating some division between the two arms of policy in the eyes of the public but these central bank interventions just reinforced the obvious fact that politics was woven through the entire structure of macroeconomic policy making, which then raised questions of accountability and democracy. The central bankers were appointed and not directly accountable to the people. Their constant interventions into broader economic policy matters thus blurred the link between voters and decision makers. This was one way in which economic policy making had been depoliticised although in this case the external authority often turned against the elected representatives rather than gave them a convenient scapegoat to divert political blame.

- Why is MMT so popular? — in which Simon Wren-Lewis declares himself a foul-weather friend, in order to have his New Keynesian cake and eat it:

Policymakers following austerity when they clearly should not annoys me a great deal, and I am very happy to join common cause with MMT on this. By comparison, the things that annoy me about MMT are trivial, like a failure to use equations and their wordplay. You will hear from MMTers that taxes do not finance government spending, or that spending comes first, but you will hardly ever see the government’s budget constraint which makes all such semantics seem silly. […] Of course having a fiscal authority following MMT and a central bank following the Consensus Assignment once rates are above their lower bound could be a recipe for confusion, unless you believe what happens to interest rates is unimportant. I personally think we have strong econometric evidence that changes in interest rates do matter, so once we are off the lower bound should we be fiscalists like MMT or should we return to the Consensus Assignment? That is a question for another day.

And then there's: - Simon Wren-Lewis, MMT, maths — Alexander Douglas in Medium:

If I want to understand how an engine works, I need to know which parts move first so I can know which parts move others and which are moved by others. Why, then, might mainstream macroeconomists like Wren-Lewis think that the actual order of spending and financing operations is irrelevant in this case? I suspect it’s because mainstream macroeconomics doesn’t care about causation; in fact, insofar as mainstream macro works via general equilibrium solutions, it can’t reasonably care about causation. There simply is no realistic causal explanation of how a general equilibrium comes about, since every unit must be assumed to be a price-taker (maybe with some stochastic Calvo stuff mixed in). In the background, there’s always some implicit appeal to a Walrasian auctioneer, or some other purely hypothetical mechanism for bringing historical processes into the citadel of eternity to become a problem with an instantaneous solution. But MMTists, like many heterodox economists, don’t work with general equilibrium models. So for them the order of operations does matter.

- The Trump Presidency, Or How to Further Enrich “The Masters of the Universe” — Noam Chomsky interviewed by David Barsamian, in TomDispatch:

At one level, Trump’s antics ensure that attention is focused on him, and it makes little difference how. […] It’s enough that attention is diverted from what is happening in the background. There, out of the spotlight, the most savage fringe of the Republican Party is carefully advancing policies designed to enrich their true constituency: the Constituency of private power and wealth, “the masters of mankind,” to borrow Adam Smith’s phrase. These policies will harm the irrelevant general population and devastate future generations, but that’s of little concern to the Republicans. They’ve been trying to push through similarly destructive legislation for years. Paul Ryan, for example, has long been advertising his ideal of virtually eliminating the federal government, apart from service to the Constituency -- though in the past he’s wrapped his proposals in spreadsheets so they would look wonkish to commentators. Now, while attention is focused on Trump’s latest mad doings, the Ryan gang and the executive branch are ramming through legislation and orders that undermine workers’ rights, cripple consumer protections, and severely harm rural communities.

- Cryptos Fear Credit — Perry Mehrling:

One of the most fascinating things about the technologist view of the world is their deep suspicion (even fear) of credit of any kind. They appreciate all too well the extent to which modern society is constructed as a web of interconnected and overlapping promises to pay, and they don’t like it one bit. […] Fiat money is untrustworthy enough, promises to pay fiat money are doubly untrustworthy. […] I view all of this through the lens of the money view, which places banking at the center of attention, views banking as fundamentally a swap of IOUs, and views money as nothing more than the highest form of credit. It is view developed not so much around a philosophical ideal but rather as a way of making sense of the operation of the world as it actually exists, outside the window as it were. In that world, the payment system is essentially a credit system, in which offsetting promises to pay clear with only very minimal use of money. And prices arise from the activity of profit-seeking dealers who absorb fluctuations in demand and supply by standing ready to take any excess onto their own balance sheet, relying on credit markets to fund the resulting inventory fluctuations. One can imagine automating a lot of that activity–and blockchain technology may well be useful for that task–but one cannot imagine eliminating the credit element. Credit is not a bug, but a feature.

- How Economists Turned Corporations into Predators — INET's Lynn Parramore interviews William Lazonick:

LP: Wait, as a stockholder I’m not an investor in the company’s capabilities?

WL: When you buy shares of a stock, you are not creating value for the company — you’re just a saver who buys shares outstanding on the stock market for the sake of a yield on your financial portfolio. Public shareholders are value extractors, not value creators. […] Agency theory aids and abets this value extraction by advocating, in the name of “maximizing shareholder value,” massive distributions to shareholders in the form of dividends for holding shares as well as stock buybacks that you hear about, which give manipulative boosts to stock prices. Activists get rich when they sell the shares. The people who created the value — the employees — often get poorer.

Sunday, 11 March 2018 - 6:15pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- A Bitcoin bet — Cameron Murray in MacroBusiness:

It is not clear what the advantage of a blockchain tracking all transactions is. My view is that this comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of money. Money is a not an object, or token. It is not a gold coin. It is a common accounting system. This is why we price in the national currency. There is nothing stopping any company setting their prices in all manner of things — gold, iron, US dollars, or other units. But we don’t. Because we want to integrate into the common system of accounting that our suppliers and customers use, and one where it makes financial sense to can keep relatively stable and predictable pricing, in addition to easy payment. Every online store that I have found that accepts Bitcoins does not price in Bitcoins. It prices in the national currency, and allows you to pay using Bitcoin. An Australian service that allows you to ‘get paid in Bitcoin’ prefers to be paid themselves in Aussie Dollars for that service.

- Google Thought I Was a Man: How Facebook and Google build a picture of who you really are — Sara Wachter-Boettcher in Nautilus:

A proxy is a stand-in for real knowledge—similar to the personas that designers use as a stand-in for their real audience. But in this case, we’re talking about proxy data: When you don’t have a piece of information about a user that you want, you use data you do have to infer that information. Here, Google wanted to track my age and gender, because advertisers place a high value on this information. But since Google didn’t have demographic data at the time, it tried to infer those facts from something it had lots of: my behavioral data. The problem with this kind of proxy, though, is that it relies on assumptions—and those assumptions get embedded more deeply over time. So if your model assumes, from what it has seen and heard in the past, that most people interested in technology are men, it will learn to code users who visit tech websites as more likely to be male. Once that assumption is baked in, it skews the results: The more often women are incorrectly labeled as men, the more it looks like men dominate tech websites—and the more strongly the system starts to correlate tech website usage with men. In short, proxy data can actually make a system less accurate over time, not more, without you even realizing it. Yet much of the data stored about us is proxy data, from ZIP codes being used to predict creditworthiness, to SAT scores being used to predict teens’ driving habits.

- Walking While Black — Garnette Cadogan, Literary Hub:

On my first day in the city, I went walking for a few hours to get a feel for the place and to buy supplies to transform my dormitory room from a prison bunker into a welcoming space. When some university staff members found out what I’d been up to, they warned me to restrict my walking to the places recommended as safe to tourists and the parents of freshmen. They trotted out statistics about New Orleans’s crime rate. But Kingston’s crime rate dwarfed those numbers, and I decided to ignore these well-meant cautions. A city was waiting to be discovered, and I wouldn’t let inconvenient facts get in the way. These American criminals are nothing on Kingston’s, I thought. They’re no real threat to me. What no one had told me was that I was the one who would be considered a threat.

- The New York Subway Conductor’s Guide to Vocal Warm Ups — Bob Vulfov, Paste Magazine:

Aside from their train’s emergency brake, a New York subway conductor’s most vital tool is their impossible-to-decipher voice. Although some subway conductors have a naturally confusing timbre to their voice, it always helps to prepare your vocal tools prior to a work shift. A few simple warm up techniques can help any conductor make even the most basic of subway announcements sound like they’re being said by an adult in Peanuts. This guide will help you conceal the words coming out of your mouth under an opaque cloud of gibberish words, trombone-like grunts, and whole sentences that sound like extended yawns.

- Self Driving — Randall Munroe, xkcd: