Sunday, 13 May 2018 - 2:52pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The blight of the visitor economy — Bill Mitchell:

One of the large funded projects that I have been involved in over the last few years concerns regional equity (in part). Our planning involves the completion of a new book (to be published sometime 2019) on the way in which regional development has become biased to the economic settlement (where jobs are created) at the expense of the social settlement (where people live). This might sound reasonable until you realise that it is another aspect of the way in which governments have abandoned their remit to ensure general prosperity, and have, instead, ‘allowed the market to work’ – which is neoliberal code for tilting the playing field in favour of corporations and global capital. One of the more recent neoliberal ruses in this context, that undermine the lived experience of local residents and boost the profits of large corporations is the concept of the ‘visitor economy’, which is the new buzzword for Tourist-led growth. Governments who claim they have run out of money are quick to hand out massive subsidies to large-scale events to promote the ‘visitor economy’. The same governments also subvert their own planning rules, encourage multi-national corporations to exploit loopholes in labour laws to cut wages and conditions, and privatise valuable public assets to ensure corporations can extract as much profit from activities as possible. Local residents’ rights are trampled in this process as corporations turn their suburbs into ‘global playgrounds’ while pocketing massive public subsidies into the bargain.

- Planes don’t flap their wings: does AI work like a brain? — Grace Lindsay in Aeon:

In 1739, Parisians flocked to see an exhibition of automata by the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson performing feats assumed impossible by machines. In addition to human-like flute and drum players, the collection contained a golden duck, standing on a pedestal, quacking and defecating. It was, in fact, a digesting duck. When offered pellets by the exhibitor, it would pick them out of his hand and consume them with a gulp. Later, it would excrete a gritty green waste from its back end, to the amazement of audience members. Vaucanson died in 1782 with his reputation as a trailblazer in artificial digestion intact. Sixty years later, the French magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin gained possession of the famous duck and set about repairing it. Taking it apart, however, he realised that the duck had no digestive tract. Rather than breaking down the food, the pellets the duck was fed went into one container, and pre-loaded green-dyed breadcrumbs came out of another.

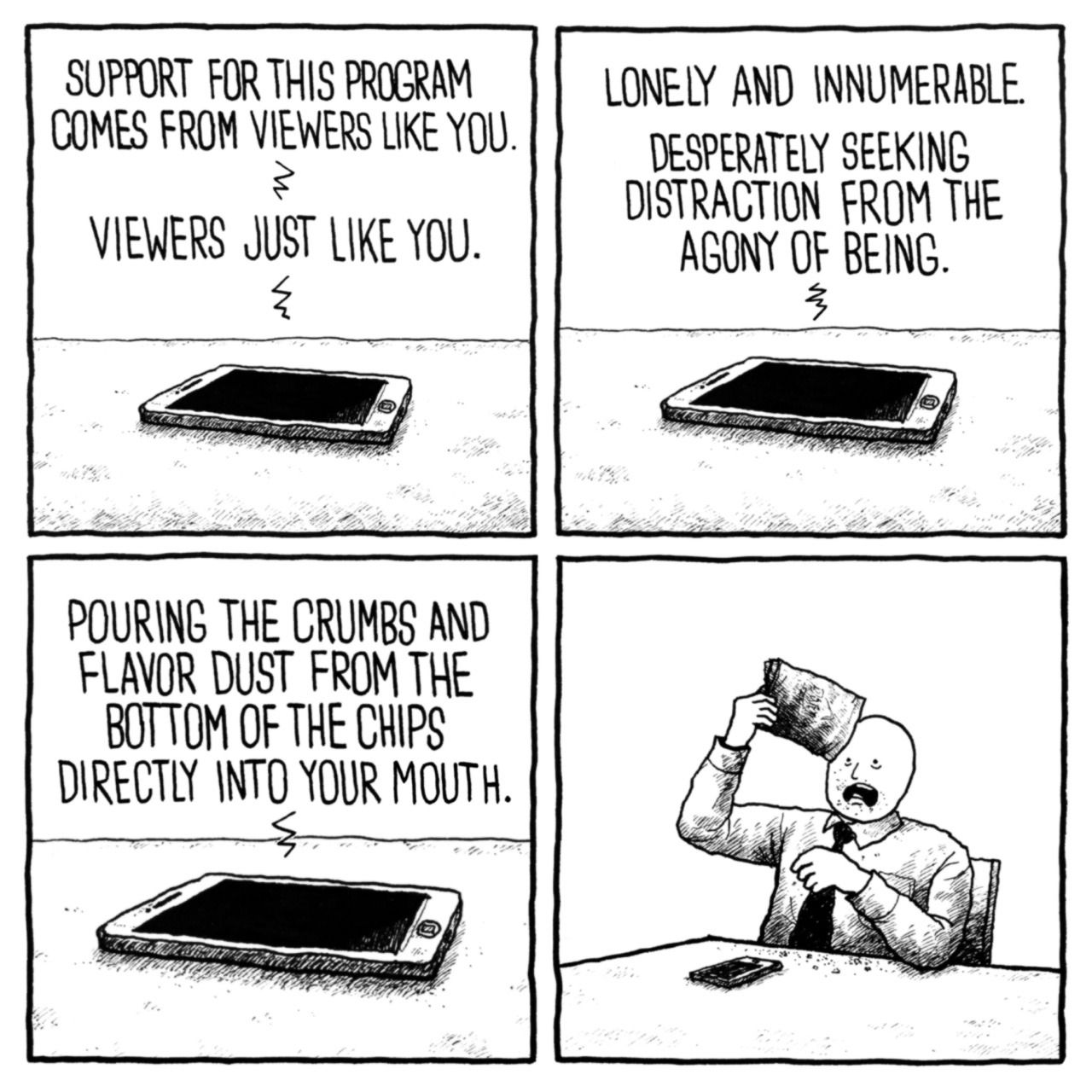

- Viewers Like You — Jake Likes Onions:

- From Whole Foods to Amazon, Invasive Technology Controlling Workers Is More Dystopian Than You Think — Thor Benson at In These Times:

In early February, media outlets reported that Amazon had received a patent for ultrasonic wristbands that could track the movement of warehouse workers’ hands during their shifts. If workers’ hands began moving in the wrong direction, the wristband would buzz, issuing an electronic corrective. If employed, this technology could easily be used to further surveil employees who already work under intense supervision. Whole Foods, which is now owned by Amazon, recently instituted a complex and punitive inventory system where employees are graded based on everything from how quickly and effectively they stock shelves to how they report theft. The system is so harsh it reportedly causes employees enough stress to bring them to tears on a regular basis.

- Buying Power: an often neglected, yet essential concept for economics — Michael Joffe at the Minskys:

In 1776, Adam Smith wrote that the degree to which a “man is rich or poor” depends mainly on the quantity of other people’s “labour which he can command, or which he can afford to purchase” (emphasis added). However, this idea of differential buying power has never been incorporated into economic theory, despite it being an obvious feature of the world we live in. The extent of a person’s disposable income and wealth gives them a corresponding degree of influence. It is like a voting system, where everybody votes for their view of what the economy should produce, but where the number of votes is very unequal. The term “power” here is best understood as meaning the degree of ability of a person or organization to bring something about. It is a causal (not e.g. a moral or political) concept. Examples of its importance are everywhere. When prices rise, some potential consumers may be excluded – a form of rationing. In pleasant locations, affluent urban dwellers buy holiday homes, crowding out the local inhabitants who do not have the buying power to compete and therefore may have to leave the area. In low-income countries, the amount of transactional sex depends on inequality (the buying power of richer men), not poverty. Any industry depends on its (potential) customers’ buying power for support: washing machine manufacture is only possible if there is a market of people who can afford their product; luxury goods such as mega-yachts exist because there are mega-rich people to buy them.

- Why Amartya Sen remains the century’s great critic of capitalism — Tim Rogan in Aeon:

Every major work on material inequality in the 21st century owes a debt to Sen. But his own writings treat material inequality as though the moral frameworks and social relationships that mediate economic exchanges matter. Famine is the nadir of material deprivation. But it seldom occurs – Sen argues – for lack of food. To understand why a people goes hungry, look not for catastrophic crop failure; look rather for malfunctions of the moral economy that moderates competing demands upon a scarce commodity. Material inequality of the most egregious kind is the problem here. But piecemeal modifications to the machinery of production and distribution will not solve it. The relationships between different members of the economy must be put right. Only then will there be enough to go around.

- Officer Friendly — This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow:

- Scientific Salami Slicing: 33 Papers from 1 Study — Neuroskeptic:

Given that scientists are judged in large part by the number of peer-reviewed papers they produce, it’s easy to understand the temptation to engage in salami publication. It’s officialy discouraged, but it’s still very common to see researchers writing perhaps 3 or 4 papers based on a single project that could, realistically, have been one big paper. But I’ve just come across a salami that’s been sliced up so thinly that it’s just absurd. The journal Archives of Iranian Medicine just published a set of 33 papers about one study.