Sunday, 26 November 2017 - 4:37pm

This week, I have been mostly not reading. Have a go at this to tide you over till next week:

- America’s ‘Retail Apocalypse’ Is Really Just Beginning — Matt Townsend, Jenny Surane, Emma Orr and Christopher Cannon in Bloomberg:

The reason isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms. There are billions in borrowings on the balance sheets of troubled retailers, and sustaining that load is only going to become harder—even for healthy chains. The debt coming due, along with America’s over-stored suburbs and the continued gains of online shopping, has all the makings of a disaster. The spillover will likely flow far and wide across the U.S. economy. There will be displaced low-income workers, shrinking local tax bases and investor losses on stocks, bonds and real estate. If today is considered a retail apocalypse, then what’s coming next could truly be scary.

Sunday, 19 November 2017 - 7:43pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Johnstown Never Believed Trump Would Help. They Still Love Him Anyway. — Michael Kruse in Politico:

Over the course of three rainy, dreary days last week, I revisited and shook hands with the president’s base—that thirtysomething percent of the electorate who resolutely approve of the job he is doing, the segment of voters who share his view that the Russia investigation is a “witch hunt” that “has nothing to do with him,” and who applaud his judicial nominees and his determination to gut the federal regulatory apparatus. But what I wasn’t prepared for was how readily these same people had abandoned the contract he had made with them. Their satisfaction with Trump now seems untethered to the things they once said mattered to them the most. “I don’t know that he has done a lot to help,” Frear told me. Last year, she said she wouldn’t vote for him again if he didn’t do what he said he was going to do. Last week, she matter-of-factly stated that she would. “Support Trump? Sure,” she said. “I like him.”

- Al Franken Just Gave the Speech Big Tech Has Been Dreading — Nitasha Tiku, in Wired:

Franken has not shied away from voicing concerns about tech’s encroachments on privacy and competition in the past, but Wednesday’s criticism was unusually sweeping, tying together a revised narrative about Silicon Valley that only emerged in glimpses during the Russia hearings. Franken argued that the same control over consumers that facilitated the spread of Russian propaganda on social media also helps Facebook and Google siphon advertising revenue from other publishers and helps Amazon dictate terms to content creators and smaller sellers. Tech giants are incentivized to disregard consumer privacy, Franken noted. “Accumulating massive troves of information isn’t just a side project for them. It’s their whole business model,” he said. “We are not their customers, we are their product.”

- Landmark study links Tory austerity to 120,000 deaths — Alex Matthews-King, the Independent:

[…] Professor Lawrence King of the Applied Health Research Unit at Cambridge University, said it showed the damage caused by austerity. "It is now very clear that austerity does not promote growth or reduce deficits - it is bad economics, but good class politics," he said. "This study shows it is also a public health disaster. It is not an exaggeration to call it economic murder.”

- Trump is trying to quietly reverse decades of social progress in America — David Usborne, the Independent:

It is to the federal courts that disputes of law always travel, some eventually landing in the Supreme Court. Where America goes next on social issues like LGBTQ rights, abortion rights, the constitutionality of the death penalty, religious rights - to name a few - will turn on rulings from federal judges. It is some of those same judges nominated by previous presidents who have blocked Trump’s travel ban. “Nobody wants to talk about it,” Trump lamented during a recent meeting of his cabinet. “But when you think about it…that has consequences 40 years out. A big percentage of the court will be changed by this administration over a very short time.”

- The world's most important asset class — Patrick Commins, Australian Financial Review:

"The definition of 'important' is malleable but try this one: name an asset class that – were it to either fall or rise in value by 30 per cent – would inexorably imply a global recession or a global boom? Oil, gold and arguably the US dollar fail that test for the simple reason that all have seen price changes of or near that magnitude this decade with little direct effect on the global economy," [Bernstein analyst Michael] Porter says. So what is the world's most important asset class now? Answer: Chinese real estate.

Sunday, 12 November 2017 - 5:01pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Why you've never heard of a Charter that's as important as the Magna Carta — Guy Standing in openDemocracy:

At the heart of the Charter [of the Forest], which is hard to understand unless words that have faded from use are interpreted, is the concept of the commons and the need to protect them and to compensate commoners for their loss. It is scarcely surprising that a government that is privatising and commercialising the remaining commons should wish to ignore it.

- How about a little accountability for economists when they mess up? — Dean Baker in Democracy Journal (via Richard Murphy and the Guardian):

Suppose our fire department was staffed with out-of-shape incompetents who didn’t know how to handle a firehose. That would be really bad news, but it wouldn’t be obvious most of the time because we don’t often see major fires. The fire department’s inadequacy would become apparent only when a major fire hit, and we were left with a vast amount of unnecessary death and destruction. This is essentially the story of modern economics.

- Electricity costs: Preliminary results showing how privatisation went seriously wrong — the Australia Institute:

Two decades ago Australia embarked on an experiment with the privatising, corporatising and marketization of the electricity sector. The proponents at the time assured the nation that everything would be better. Clearly that is not the case; between December 1996 and December 2016 Australian prices increased by 64 per cent but electricity prices increased by 183 per cent […] In this paper we have examined the type of labour employed now compared with two decades ago. Electricity is now management heavy with a blow out in the number of managers relative to other workers. In addition electricity now employs an army of sales and marketing and other workers who do not actually make electricity.

- How to Sneeze Like I Do — the Oatmeal:

- We should take pride in Britain’s acceptable food — David Mitchell being all David-Mitchelly in the Guardian:

A phrase really jumped out at me from a newspaper last week. The Times said a recent survey into Spanish attitudes to Britain, conducted by the tourism agency Visit Britain, “found that only 12% of Spaniards considered the UK to be the best place for food and drink”. That, I thought to myself, may be the most extraordinary use of the word “only” I have ever seen. […] Because, if “only” still means what I think it means, the paper is implying it expected more than 12% of the people of Spain to think Britain was “the best place for food and drink”. That’s quite a slur on the Spanish. How delusional did it expect them to be? What percentage of them would it expect to think the world was flat? I know we’re moving into a post-truth age, but 12% of a culinarily renowned nation considering Britain, the land of the Pot Noodle and the garage sandwich, to be the world’s No 1 destination for food and drink is already a worrying enough finding for the Spanish education system to address. It would be vindictive to hope for more.

- Reinventing the wheel — Chris Dillow:

In both the UK and US, wage inflation has stayed low despite apparently low unemployment – to the puzzlement of believers in the Philips curve. Felix Martin in the FT says there's a reason for this. The “dirty secret of economics,” he says, is “the central importance of power.” Inflation, he says, is “society’s default method of reconciling, at least for a while, irreconcilable demands.” And because workers don't have the power to make big demands, we haven’t got serious inflation. What's depressing about this isn’t just that it’s right, but that it needs saying at all.

Sunday, 5 November 2017 - 4:29pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Little Black Box That Took Over Piracy — Brian Barrett, WIRED:

Kodi itself is just a media player; the majority of addons aren't piracy focused, and lots of Kodi devices without illicit software plug-ins are utterly uncontroversial. Still, that Kodi has swallowed piracy may not surprise some of you; a full six percent of North American households have a Kodi device configured to access unlicensed content, according to a recent Sandvine study. But the story of how a popular, open-source media player called XBMC became a pirate's paradise might. And with a legal crackdown looming, the Kodi ecosystem's present may matter less than its uncertain future.

- Freedom for the Many — Shant Mesrobian in Jacobin:

After salary or wages, the most significant part of the [US] employment contract tends to be health insurance. And employers know it. The resulting dependency and vulnerability is especially acute when a worker’s entire family relies on them for health coverage (particularly if one of their family members has a chronic or life-threatening disease). In such cases, health insurance surpasses even monetary compensation as the primary motivation for maintaining employment. When your child has cancer, it’s that much harder to speak up about your boss’s sexual harassment. […] Lack of health insurance (and college debt, and middling disability benefits — the list goes on) severely limits a person’s ability to choose which career to pursue, where to live, when to start a family, how many children to have, and what types of hobbies to take up. In short, it’s not about free stuff — it’s about a free life.

- The Angriest Librarian Is Full of Hope — Alex Halpern in CityLab:

Those mousy, quiet librarians are a thing of the past, if in fact they ever existed at all outside of Hollywood. Today, depending on the community they serve, a public librarian is part educator, part social worker, and part Human Google. What they aren’t is a living anachronism, an out-of-touch holdout in a dying job who’s consigned to a desk, scolding kids for returning books a few days late.

- Monopoly was invented to demonstrate the evils of capitalism — Kate Raworth in the Conversation:

‘Buy land – they aren’t making it any more,’ quipped Mark Twain. It’s a maxim that would certainly serve you well in a game of Monopoly, the bestselling board game that has taught generations of children to buy up property, stack it with hotels, and charge fellow players sky-high rents for the privilege of accidentally landing there. The game’s little-known inventor, Elizabeth Magie, would no doubt have made herself go directly to jail if she’d lived to know just how influential today’s twisted version of her game has turned out to be. Why? Because it encourages its players to celebrate exactly the opposite values to those she intended to champion.

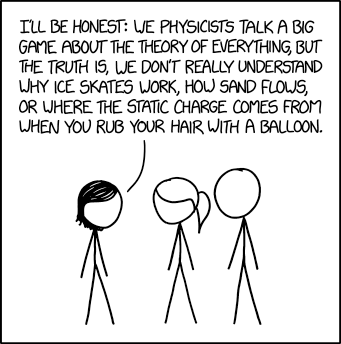

- Physics Confession — xkcd:

- Willmot now last Sydney suburb with a median house price under $500,000 — Nicole Frost at Fairfax's dog-wagging tail Domain (via MacroBusiness):

There are just 632 houses located in the suburb, which was established in the early 1970s and named for the first president of the Blacktown Shire Council, Thomas Willmot. The majority of the suburb’s homes are owned by investors. It has been this feverish investor activity that has led to the disappearance of Sydney’s sub-$500,000 suburbs. At the start of the year there were four and five years ago there were more than 150.

- The wilderness years: how Labour’s left survived to conquer — Andy Beckett, the Guardian:

In the vast literature written about Labour between the 1980s and 2015 – all the fat gossipy memoirs, diaries and biographies, confident overviews by journalists and historians, and careful analyses by political scientists – there is an absence, which has seemed ever larger and more puzzling since Corbyn was overwhelmingly elected leader. He and his closest comrades for decades – John McDonnell, now shadow chancellor, and Diane Abbott, now shadow home secretary – rarely feature. They are not in books about the 2003 Iraq war, which they all opposed. They are hardly in books about New Labour; or about the Conservative government and its austerity policies, which they opposed when their party barely did. They do not even feature much in studies of Labour’s startling success in London, where they all have constituencies and have hugely increased their majorities since the 90s.

Sunday, 29 October 2017 - 7:59pm

Oy, this week… My life! 'Ere's all I can offer. For you and you only. Top quality schmutter. I'm cuttin' me own froat gaw blimey:

- The End of Cash; The End of Freedom — Ian Welsh:

Every time someone talks about getting rid of cash, they are talking about getting rid of your freedom. Every time they actually limit cash, they are limiting your freedom. It does not matter if the people doing it are wonderful Scandinavians or Hindu supremacist Indians, they are people who want to know and control what you do to an unprecedentedly fine-grained scale. […] Cash isn’t completely anonymous. There’s a reason why old fashioned crooks with huge cash flows had to money-launder: Governments are actually pretty good at saying, “Where’d you get that from?” and getting an explanation. Still, it offers freedom, and the poorer you are, the more freedom it offers. It also is very hard to track specifically, i.e., who made what purchase.

- The economics of BBC pay — Chris Dillow:

Take, for example, Peter Capaldi, who earned less than £250,000. This doesn’t seem much, given that the joint surplus is huge – Doctor Who is a worldwide hit – and Capaldi’s ability so great as to give him lots of outside options. But it’s more understandable, once we recognise two things. One is that the BBC’s fall-back position is strong: Doctors are replaceable and the format’s success doesn’t depend upon the actor – and that being the Doctor gives Capaldi a fantastic basis for negotiating his next job; it's worth being temporarily underpaid for that.

Sunday, 22 October 2017 - 6:24pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Modern Economists: The Inept Firefighters’ Club — Dean Baker in Democracy Journal:

The problem is not that modern economics lacks the tools needed to understand the economy. Just as with firefighting, the basics have been well known for a long time. The problem is with the behavior and the incentive structure of the practitioners. There is overwhelming pressure to produce work that supports the status quo (i.e. redistributing to the rich), that doesn’t question authority, and that is needlessly complex. The result is a discipline in which much of the work is of little use, except to legitimate the existing power structure.

- ANZ: Australia “place of choice” for property money laundering — Leith van Onselen at MacroBusiness:

Legislation to implement the second tranche of anti-money laundering (AML) legislation covering real estate gate keepers has been gathering dust for a decade. The end result is that realtors, lawyers, accountants and other real estate gate keepers are currently exempted from AML requirements. And this exemption has provided an easy avenue for foreign buyers to launder funds through Australian property.

- I have run out of interesting things to write about edtech — Jonathan Rees:

What I’ve learned in my years of studying this topic, is that there are actually a ton of really devoted people who are trying to develop and utilize various educational technologies to create useful and – at least in some cases – superior experiences to how colleges and classes operate now. These efforts are, as you might expect, hugely labor intensive. Therefore, they seldom appeal to private Silicon Valley companies trying to make a quick buck. They do, however, appeal to all of us who are in higher education for the long run and a willing to try something new.

- Universities' greed and phony prestige to blame for appalling drop-out rates — Tracie Winch in the Sydney Morning Herald:

In terms of classroom engagement, it's fair to say that the centuries-old method of formal lectures and tutorials is outdated, but simply shunting classes online is not the answer and, of itself, it certainly isn't innovative. It's sending a message to students saying "hey you don't really need to show up" and so the majority don't – unless there is some kind of assessment hurdle attached. And we are shocked?

- America’s hidden philosophy — John McCumber in Aeon:

As far as rational choice theory is concerned, it doesn’t matter if I want to end world hunger, pass the bar, or buy myself a nice private jet; I make my choices the same way. Similarly for Cold War philosophy – but it also has an ethical imperative that concerns not ends but means. However laudable or nefarious my goals might be, I will be better able to achieve them if I have two things: wealth and power. We therefore derive an ‘ethical’ imperative: whatever else you want to do, increase your wealth and power! Results of this are easily seen in today’s universities. Academic units that enable individuals to become wealthy and powerful (business schools, law schools) or stay that way (medical schools) are extravagantly funded; units that do not (humanities departments) are on tight rations.

- Why Race Is Not a Thing, According to Genetics — Simon Worrall interviews geneticist Adam Rutherford for National Geographic:

It says something about us that we look for simple answers to complex questions. Inevitably, people have turned to the relatively new science of genetics to try to explain otherwise unfathomable human behaviors, such as spree killing or murder. […] If we sequenced [mass-shooter] Adam Lanza’s genome, we would simply find that he has a human genome and that all the variants in him would be found in other people that don’t commit spree killings. Turning to genetics to try and find out why this guy killed all of those kids in this wicked act completely misses the point! The single common factor in all spree killings is access to guns. That seems straightforward to me.

Friday, 20 October 2017 - 12:42pm

When you don't have a job, it's particularly annoying to see so many people who can't do theirs:

"The memorable songs kept on coming with the group delving back to its earliest days then playing the songs that made the Oils one of the biggest acts in the world.

"The end of each number leaving the crowd calling out for more.

"All except one that was.

"After half a dozen songs one crowd member was escorted out for drunken behaviour which led Garrett to make a speech about how they expect their fans to be courteous and have consideration for all.

"A message reiterated with a section of the UN convention in big letters draped above the stage reminding all that every human being is worthy of the same respect and rights.[…]

"If the open air venue had a roof, when The Power And The Passion was performed it would've well and truly been blown off.

"The die-hard fans who raced to the front row when the gates opened four hours before the headline act hit the stage weren't disappointed when the memorable show came to an end."

As it turns out, I am practically eating from the palm of the reviewer's hand. The one sentence per-paragraph rule is, frankly, a relief when so often these days one has to deal with multiple ideas without a whitespace breather.

A string of random words also counts as a sentence.

A sentence of Hemingway-esque minimalist brilliance that is.

If this review had a roof, or an editor, it would have been well and truly blown off. I'm now going to delay reading the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights to read instead "the UN convention in big letters". I'm getting on a bit, so I can't ignore the fact that my eyes are the same age as the rest of me. I don't know why it's not common practice to publish large print editions of international agreements.

There is a lot to think about here. It's been memorable, but I wasn't disappointed to get to the end of it.

Users and groups in Debian: getting it right

So ideally when I set up a new computer, I want all the users I trust — including, by necessity and regrettably, myself — to be in the staff group, and all the files they create to be by default writable by anyone in that group. This ought to be easy, and in fact now is, but has changed repeatedly over the decades I've been using Debian GNU/Linux, so I can never remember how it's done, hence this note.

You will need to do all this as root, and to be on the safe side, make sure any user(s) you want to put into the staff group are not currently logged in, as files and directories in the affected home directories will be reassigned to the group, which (I guess) won't work for any currently opened by a running process.

If you enable the pam_umask PAM module, you will only need to configure group-writability once, and it will work regardless of whether you're logging in locally, SSHing, or whatever. As root, edit /etc/pam.d/common-session to include this line:

session optional pam_umask.so

Then edit the umask line in /etc/login.defs like so:

UMASK 002

If yours isn't a fresh Debian install, the umask setting may already have been overridden in one or more of:

/etc/profile/etc/bash.bashrc~/.profile~/.bashrc

If so, delete or comment out where necessary. (Source)

Adding a user to the staff group is:

usermod -a -G staff myusername

Making staff the user's primary group — the one which by default newly created files and directories are owned by — is just:

usermod -g staff myusername

Too easy.

Sunday, 15 October 2017 - 3:01pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Seven Deadly Sins of AI Predictions — Rodney Brooks in MIT Technology Review:

I recently saw a story in MarketWatch that said robots will take half of today’s jobs in 10 to 20 years. It even had a graphic to prove the numbers. The claims are ludicrous. (I try to maintain professional language, but sometimes …) For instance, the story appears to say that we will go from one million grounds and maintenance workers in the U.S. to only 50,000 in 10 to 20 years, because robots will take over those jobs. How many robots are currently operational in those jobs? Zero. How many realistic demonstrations have there been of robots working in this arena? Zero.

- Socialism with a spine: the only 21st century alternative — John Quiggin in the Guardian:

For most of the current political class whose ideas were formed in the last decades of the 20th century, the superiority of markets over governments is an assumption so deeply ingrained that it is not even recognised as an assumption. Rather, it is part of the “common sense” that “everyone knows”. Whatever the problem, their answer is the same: lower taxes, privatisation and market-oriented “reform”. Unsurprisingly, people are looking for an alternative, and many are looking back at the postwar decades of widely shared prosperity.

- Disrupt the Disrupters: Uber’s Comeuppance is the Moment for the U.S. to Finally Start Regulating the So-called Sharing Economy — Dean Baker in the New York Daily News:

The company's effective motto, that it is better to ask for forgiveness than permission, seemed to cry out for a swift slap to the face. Taxis are hardly new, but the Uber gang claimed that the whole set of regulations developed around the industry didn't apply to them because they were an app-based "ride hailing" platform, not a taxi company. This was, and is, garbage; as are most of the claims for the "newness" and "uniqueness" of the sharing economy companies. […] The only thing that was really new about Uber, Airbnb and the other sharing economy companies was the claim that they should be exempt from longstanding rules and regulations.

- The Skills Gap: Blaming Workers Rather than Policy — Dean Baker in the Hankyoreh:

First and foremost we are not seeing the sort of rapid wage growth that would be expected if there were widespread skills shortage. This is a story where companies would like to expand their business but are prevented from doing so because they can’t find any workers with the skills they need. However there are always some workers somewhere who have the needed skills. Companies could offer higher wages to lure workers away from competitors. Or, they can make a point of recruiting in more distant areas and offering to pay travel and location expenses for workers. We don’t see this sort of bidding war for workers taking place in any major sector of the economy. While there may be a few occupations in a few areas where employers really are bidding up wages rapidly, this is not happening in most sectors of the labor market.

- Myths of Job-Killing Robots Obscure Real Causes of Inequality — Dean Baker, evidently a busy man, in Truthout:

If we just considered the cost of physically producing robots, they should be cheap. We should all be able to buy a robot for a few hundred dollars that would cook our food, clean our house, mow our lawns, and do all sorts of other tasks that are time-consuming, unpleasant and often involve substantial expenses. In this case, robots should be leading to rapid increases in real wages and living standards. However, if robots are expensive and therefore redistributing large amounts of money from ordinary workers to the people who own robots, it is because of the patent and copyright monopolies associated with building robots.

- Universal basic services could work better than basic income to combat 'rise of the robots', say experts — Ben Chapman in the Independent:

The Institute has put forward the set of ideas, which it calls ‘universal basic services”, as a more achievable and more desirable alternative to universal basic income (UBI). […] Instead of attempting to alleviate poverty through redistributive payments and minimum wages, the state should instead provide everyone with the services they need to feel secure in society, the report’s authors argue.

- Where is Australia's Jeremy Corbyn? — Martin Hirst, Independent Australia:

The Labor Party has been deradicalised. The Left has not been strong inside the ALP for decades, the membership is in decline and it is ageing. The Labor "Left" is a faction tied together by two things: the first is ambition (lefties want that safe seat and pension too), the second is that they would be in the Right faction if the Right faction wasn’t quite so horrible to women and gays. In other words, the leftism of the Labor Left is "left" because it’s not "right". The ALP Left is about as left as your left arm when compared to your right. It is essentially the same thing. This is the real reason we don’t have a Jeremy Corbyn to cheer for.

- A Job-Killing Robot for Rich People — Dean Baker, this time at Jacobin:

An FTT is usually seen as a way to raise large amounts of revenue (in the US, it could possibly generate as much as $190 billion a year, or 1 percent of GDP). Or it is viewed as a means to limit speculative trading in the financial sector, potentially making markets less volatile. The best argument for an FTT, however, is that it can sharply reduce some of the highest incomes in the economy by curtailing the trading that makes those incomes possible. As a result, it can play a large role in reversing the upward redistribution of income that we’ve seen over the last four decades.

- My own private basic income — Karl Widerquist, :

Just because I benefit from the unfairness of our economic system doesn’t make its rules any fairer. Those rules are not some natural feature of the universe. People made them. People can change them. Why don’t we? […] Some people who read this story will probably accuse me of hypocrisy, saying something like, “If you’re an egalitarian, why are you rich?” If I wrote a similar description of the economy when I was poor, they’d accuse me of jealously, saying something like, “if you’re so smart, why aren’t you rich?” That’s the catch-22 for people who complain about the rules of our economic system. You’re either hypocritical or jealous. No one has the right amount of property to complain about the distribution of property.

- The 2017 general election marked the popping of the Blair-Clinton bubble — David Graeber in New Statesman:

How did we get to the point where the candidate of a major party was judged not by his political vision, programme or sensibilities, but by an estimation of how different classes of imagined voters were likely to respond to him? How is it that this has become our basic standard for judging politicians? And by “we” I am referring not just to political junkies, professional or otherwise, but to the electorate as a whole. […] I remember looking through the comments sections of articles on Labour's prospects last year, and being startled that almost every single person emphasised not what Corbyn stood for – those who did mostly claimed approval – but rather “electability” issues. No one would vote for him. Therefore, there was no point in voting for him. The remarkable thing is that there were thousands of these commentators. Collectively, they were a substantial chunk of the electorate. And here they were saying they wouldn't vote for a candidate whose views they agreed with because they assumed no one else would.

- Why we need need more national debt — Richard Murphy:

It’s a fact that the UK government does not need to issue debt. In the modern era of money the Bank of England can create any amount of money that the government requires without having to borrow or tax a penny of the sum in question. That is because all money is now, as a matter of fact, created out of thin air when banks lend money, including when (as might be legal again after Brexit) the Bank of England lends directly to the Treasury. This is because all money is debt: if in doubt read what it says on a UK bank note, and realise that these are just debt, a fact that is confirmed by this cash being included in the national debt in the UK’s government accounts.

Moreover… - The UK national debt is not 89% of GDP; it’s only 67% of GDP and it’s time the government and media stopped lying about this — Richard Murphy:

Suppose you owe your mortgage to yourself. Would you worry about repaying it? Or come to that worry about the interest on it? And would you worry about when you repaid it? Of course you wouldn’t. And you’d be right not to do so. That’s because the idea of owing yourself money is meaningless, and makes the debt irrelevant. Which is precisely what this £435 billion of debt is: it is irrelevant. Indeed, as I have shown, it is actually shown as cancelled debt in the UK national accounts, which is precisely what it is. It literally no longer exists.

- Bafflersplainer: Win the Future — David Rees in the Baffler:

Rather than spending their money supporting progressive local and state groups that could do the grinding organizational work of registering new voters, challenging racist voter ID laws, and pushing back against gerrymandering, Win the Future’s founders will do a bunch of high-profile stuff online. This will increase civic participation where it counts most: on the internet. Remember, Pincus’s shattering experience of exclusion came after the DNC refused to respond to the five paragraphs of suggestions he submitted to its website. As we all know, it’s the comment box, not the ballot box, where democracy lives or dies.

- “Money from nothing” – my newspaper article translated into English — Dirk Ehnts:

Banks do not need savers to extend loans. They are not intermediaries, but create money by themselves. The Bundesbank says that unequivocally. The prose is a bit awkward, nevertheless it is worthwhile to read the main passage: „If a bank extends a loan, she books the credit to the customer connected to the loan as his deposit […] This refutes a widely held erroneous view in which the bank acts as an intermediary in the moment of lending, in which loans can only be funded by deposits that the bank has received from customers before.“ Harvard professor Gregory Mankiw with his theory of intermediation, so says Bundesbank, subscribes to „a widely held erroneous view“.

- Not even Paul Krugman is a real Keynesian — Jonathan Schlefer in the Boston Globe profiles Lance Taylor and Duncan Foley:

Keynes’s insights have enormous practical importance, according to Lance Taylor and Duncan Foley of the New School. […] But isn’t Keynes now mainstream? No, say Foley and Taylor. The mainstream still sees economies as inherently moving to an optimal equilibrium, as Wicksell did. It still says demand causes short-run fluctuations, but only supply factors, such as the capital stock and technology, can affect long-run growth.

Tuesday, 10 October 2017 - 7:58pm

Coffs Harbour is defined by the NSW Government's 2036 North Coast Regional Plan as a regional city and it does home a Southern Cross University campus.

I would love Coffs Harbour to become a university city. The trouble is that SCU is a vocational college that happens to have the word "university" in it's brand name. Last year the incoming Vice Chancellor, who in a stunning departure from the norm for bottom-tier uni VCs is not an out-and-proud philistine, nonetheless wrote to students "I want to assure you that your employability and your future career success are top priorities for all of us."

Obviously somebody who has the ability and inclination to pursue an academic education will inevitably also be employable, but SCU does not offer an academic education. All the work a student does is assessed against predetermined "marking criteria", which refer to desired "learning outcomes", which are in turn linked to "graduate attributes", which ultimately answer to the needs of employers. It's a TAFE with airs and graces. It's three additional years of high school with a much narrower range of subjects and virtually no permanent full-time teaching staff. And under the "demand driven system" it has a commercial imperative to take all comers, and ensure as many as possible complete courses which are consequently so dumbed-down as to be meaningless.

The post-1988 expansion of alleged higher education is a scam built on the hoax of "human capital". By flogging a false promise of employability instead of contributing to the intellectual life of its host community, SCU Coffs is merely the largest leech in the swamp in which it sits.