colonialism

America’s informal empire – what really went wrong in the Middle East

In this edited excerpt from the introduction to What Really Went Wrong, Fawaz A Gerges argues that US interventionism during the Cold War – especially in Iran and Egypt – steered the Middle East away from democracy towards authoritarianism, shaping the region’s political and economic landscape for decades to come.

At the end of the colonial era after World War Two, the Middle East was on the cusp of a new awakening. Imperial Britain, France, and Italy were discredited and exhausted. Hope filled the air in newly independent countries around the world. Like people across the decolonised Global South, Middle Easterners had great expectations and the material and spiritual energy needed to seize their destiny and modernise their societies. Few could have imagined events unfolding as disastrously as they did. Yet by the late 1950s, the Middle East had descended into geostrategic rivalries, authoritarianism and civil strife.

At the end of the colonial era after World War Two, the Middle East was on the cusp of a new awakening. Imperial Britain, France, and Italy were discredited and exhausted. Hope filled the air in newly independent countries around the world. Like people across the decolonised Global South, Middle Easterners had great expectations and the material and spiritual energy needed to seize their destiny and modernise their societies. Few could have imagined events unfolding as disastrously as they did. Yet by the late 1950s, the Middle East had descended into geostrategic rivalries, authoritarianism and civil strife.

What clouded this promising horizon? Digging deep into the historical record, What Really Went Wrong critically examines flashpoints like the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s ousting of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq in August 1953 and the US confrontation with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the mid-1950s. My argument is that such flashpoints sowed the seeds of subsequent discontent, hubris and conflict. I zero in on these historical ruptures to reconstruct a radically different story of what went wrong in the region, thus correcting the dominant narrative. My goal is to engender a debate about the past that can make us see the present differently.

What Really Went Wrong critically examines flashpoints like the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s ousting of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq in August 1953 and the US confrontation with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the mid-1950s.

I argue that the defeat and marginalisation of secular-leaning nationalist visions in Iran and Egypt in the 1950s and ’60s allowed for Sunni and Shia pan-Islamism to gain momentum throughout the Middle East and beyond. Because of bad decisions made in the White House, power passed from popular leaders and sincere patriots to unpopular and subservient rulers, and the sympathy of the people was hijacked by Islamist leaders and movements. The consequences of events in both Iran and Egypt still haunt the Middle East today.

The dawn of US interventionism

The book’s core concern is with the legacy and impact of US foreign policy during the early years of the Cold War on political and economic development in the Middle East. It focuses on two major pieces of the puzzle: momentous events in Iran and Egypt in which America played a decisive role. Examining these, it shows how Anglo-American interventions in the internal affairs of the Middle East from the early 1950s (till the present) stunted political development and social change there and led the region down the wrong path to authoritarianism and militarism. The Middle East was reimagined as a Cold War chessboard, which left a legacy marked by dependencies, weak political institutions, low levels of civil and human rights protection, lopsided economic growth and political systems prone to authoritarianism. This is the antithesis of often-stated Western values rooted in democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

An informal empire emerges

Developing countries emerged into independence from a history that left its mark on their future. It was difficult enough for countries emerging from colonialism to build sound institutions, gain public trust and extend state authority, and America’s imperial ambitions and actions during and after the Cold War made this all the more difficult, if not impossible. With the foundations of imperialism far from completely dismantled, old structures persisted under new names. In some cases, it was more than just structures that perpetuated dependence. It was the very leaders and their descendants who were co-opted into a neocolonial reality. Anyone challenging that order was swiftly marked as an enemy of democracy and free markets.

With the foundations of imperialism far from completely dismantled, old structures persisted under new names.

Within living memory, the peoples of the Middle East viewed the US with awe and optimism. Unlike its European allies, America had never ruled over Muslim lands and appeared to have no imperial ambitions. Instead, Americans had built hospitals and major universities in the region. Washington could have built relations on the basis of mutual interests and respect, not dependency and domination. When the US signed an agreement with Saudi Arabia to begin oil exploration in 1933, the people of the region saw it as an opportunity to decrease their dependence on the “imperial colossus,” Great Britain. But from the Middle East to Africa and Asia, newly decolonised countries discovered that formal independence did not translate into full sovereignty. A creeping form of colonialism kept tying these countries to their old European masters and the new American power.

As the historian Rashid Khalidi noted, the US was following in the footprints of European colonialism. In his book Imperialism and the Developing World, Atul Kohli compares British imperialism during 19th century with America’s informal empire in the 20th. It might not have been formally called colonialism, but the effects were the same: Washington – often backed by London – pursued its interests at the cost of the right to self-determination and sovereignty of other peoples and countries.

Cold War divisions, US opportunism

Setting up defence pacts in the Middle East in the early 1950s to encircle Russia’s southern flank, Eisenhower’s Cold Warriors pressured friends and foes to join in America’s network of alliances against Soviet communism. Newly decolonised states like Iraq, Egypt, Iran (which was not formally colonised), and Pakistan had to choose between jumping on Uncle Sam’s informal empire bandwagon or being trampled under its wheels.

The Truman and Eisenhower administrations laid the foundation of an imperial foreign policy which was hardened by the Nixon and Reagan presidencies. The US provided arms, aid and security protection to the shah and to Israeli and Saudi leaders during the Cold War. This led to economic growth, but as Kohli notes, it was not evenly distributed throughout the region. After the end of the Cold War in 1989, US imperial foreign policy persisted with George W. Bush, who waged a global war on terror that saw the US invade and occupy Afghanistan and Iraq.

The US foreign policy establishment saw the world through imperial lenses that divided everything into binary terms – black and white, good and evil. In their eyes, the existential struggle against Soviet communism justified violence, collective punishment and all other means to achieve their ideological ends. In June 1961, then-CIA director Allen Dulles, declared that the destruction of the “system of colonialism” was the first step to defeat the “Free World.”

While establishing this foreign policy strategy, the US […] was also building the postwar international financial and trading and security institutions that allowed its competitive corporations to outperform others.

While establishing this foreign policy strategy, the US – as the dominant capitalistic superpower – was also building the postwar international financial and trading and security institutions that allowed its competitive corporations to outperform others. This global system of open, imperial economies disproportionately steered the fruits of the world’s economic growth to the citizens of the West, particularly Americans. Kohli argues that the US sought to tame sovereign and effective state power in the newly decolonised world. Regime change, covert and overt military interventions, sanctions to create open economies and acquiescent governments were all among the weapons of the informal Cold War imperialism, all wielded with the soundtrack of piercing alarm about the spectre of a Soviet communist threat.

The “Free World” fallacy

The project was not without opposition, however. Nationalist forces resisted the new imperialism, and US leaders escalated their military efforts to defeat indigenous opposition. With its thinly veiled imperialism, insubstantial justification for using military force and vague claims about impending threats to the “homeland”, the US began to lose credibility. Washington’s shortsighted views ultimately backfired, undermining security globally and forestalling good governance in the Middle East and beyond.

This imperial vision had ramifications for the West’s self-appointed role as the leader of the free world and defender of human rights, going well beyond reputation.

This imperial vision had ramifications for the West’s self-appointed role as the leader of the free world and defender of human rights, going well beyond reputation. Mistrust in the international liberal order has weakened international institutions and eroded deference to norms such as respect for human rights. What unfolds in Guantánamo Bay or Gaza, Palestine does more than hurt the individuals unjustly subject to illegal torture or civilians slaughtered by the thousands; it raises the global public’s tolerance for such abhorrent acts by having them unfold in the heart of the democratic West.

Understanding what happened in the Middle East

The book does not argue that democracy was bound to flourish in the Middle East if the US had not subverted the nascent democratic and anticolonial movements. Rather, America’s military intervention, its backing of authoritarian, reactionary regimes and neglect of local concerns, and its imperial ambitions created conditions that undermined the lengthy, turbulent processes that constitutionalism, inclusive economic progress, and democratisation require. The political scientist Lisa Anderson notes that “it is usually decades, if not centuries, of slow, subtle, and often violent change” that create the conditions for meaningful state sovereignty.

Though the experiences of the Middle East are not wholly unique, some characteristics are specific to the region, such as its contiguity to Europe and its vast quantities of petroleum, strategic waterways and markets which have proved irresistible to Western powers. Western powers have thus persistently intervened in the internal affairs of Middle Eastern countries as they have not in other parts of the world. This “oil curse” has triggered a similar geostrategic curse in the Middle East, pitting external and local powers against each other in a struggle for competitive advantage and influence. As the book explores, this convergence of curses has had far-reaching and lasting political and economic consequences for Middle Eastern states.

The book eschews historical determinism and offers a robust reconstruction of the international relations of the Middle East as well as social and political developments in the region. It also encourages us to reimagine the present in light of revisiting the past. In so doing, we can begin to see lost opportunities and new possibilities for healing and reconciliation.

Note: This excerpt from the introduction to What Really Went Wrong: The West and the Failure of Democracy in the Middle East by Fawaz A Gerges is copyrighted to Yale University Press and the author, and is reproduced here with their permission.

This book extract gives the views of the author, not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Read an interview with Fawaz A Gerges, “What really went wrong in the Middle East” from March 2024 for LSE Research for the World.

Watch Fawaz A Gerges interviewed by Christiane Amanpour about the US’s role in the Israel-Gaza war from December 2023 and by Fareed Zakaria about the prospect of a regional war in the Middle East from January 2024, both on CNN.

Main image: Secretary Dean Acheson (right) confers with Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran (left) at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington D.C., 1951. Credit: The Harry S. Truman library.

Q and A with Nick Couldry and Ulises A Mejias on Data Grab

In this interview with Anna D’Alton (LSE Review of Books), Nick Couldry and Ulises A Mejias discuss their new book, Data Grab which explores how Big Tech ushered in an exploitative system of “data colonialism” and presents strategies on how we can resist it.

Nick Couldry and Ulises A Mejias will speak at a public LSE event to launch the book on Tuesday 14 May at 6.30pm. Find out more and Register.

Q: What is data colonialism and how does it relate to historical colonialism?

Q: What is data colonialism and how does it relate to historical colonialism?

Data colonialism, as we define it, is an emerging social order based on a new attempt to seize the world’s resources for the benefit of elites. Like historical colonialism, it is based on the extraction and appropriation of a valuable resource. The old colonialism grabbed land, resources and human labour. The new one grabs us, the daily flow of our lives, in the abstract form of digital data. And, crucially, this new colonialism does not replace the old colonialism, which very much still continues in its effects. Instead, it adds to the historically enduring process of colonialism a new toolkit, a toolkit that involves collecting, processing, and applying data.

The old colonialism grabbed land, resources and human labour. The new one grabs us, the daily flow of our lives, in the abstract form of digital data.

We are not saying there is a one-to-one correspondence between the old colonialism and the new, expanded one. The contexts, the intensities, the modalities or colonialism have always varied, even though the function has remained the same: to extract, to dispossess. And violence continues to reverberate along the same inequalities created by colonialism. We personally may even benefit from the system. We might not mind giving up our data, because we are the ones using gig workers; we are not the gig workers themselves. We are the ones who don’t get to see violent videos on YouTube, because someone in the Philippines has done the traumatising work of flagging and getting those videos removed (while working for very low wages). These are not the same kinds of colonial brutalities of yesterday, but there is still a lot of violence in these new forms of exploitation and the whole emerging social order of data colonialism is being built on force, rather than choice.

Q: Why is it important to frame Big Tech’s extraction of data to form “data territories” as a colonial enterprise? How is data territorialised and extracted?

Something central to colonialism (and capitalism) is the drive to continue accumulating more territories. Colonisers are always looking for new “territories” or “frontiers” from which to extract value. Lenin once said something to the effect that imperialism is the most advanced form of capitalism: once you run out of people to exploit at home, you must colonise new zones of extraction that also become new markets for what you are selling. That is the strategy behind data colonialism, seen as the latest landgrab in a very long series of resource appropriation.

Once you run out of people to exploit at home, you must colonise new zones of extraction that also become new markets for what you are selling. That is the strategy behind data colonialism

Data colonialism is a system for making people easier to use by machines. Corporations have, in many cases, managed to monetise that data by using it to influence our commercial and political decisions, and by selling our lives back to us (the platform can “organise” your life for you and even track and predict your health and emotions). And even where data cannot be directly monetised, accumulated or anticipated data still generates value in terms of speculative investments that build stock market value.

We are not saying that all extracted data necessarily becomes a valuable commodity. Data markets are complex and still developing: much data retains greater value when kept and used inside corporations, rather than being sold between corporations. But value has been extracted all the same through the process of abstracting human life in the form of data.

Q: Data extractivism or “social quantification” is being embedded into our lives in sectors from health and education to farming and labour. How is it reshaping society?

When the internet was not yet controlled by a handful of corporations, we were told that it could be the ultimate tool for democratisation, because it allowed the sharing of information from many to many. Today, what we have is a monopsony, a market structure characterised by a handful of “buyers” (the platforms that “buy” our data or rather acquire it for free). So many-to-many communication cannot happen without first going through a many-to-one filter, concentrating power in a few hands.

In addition to this, the people who manage this system have become quite adept at fragmenting the public into communities that mistrust and hate each other (often called filter bubbles, or echo chambers, though some prefer to think in terms of wider forces of polarisation). The original intent was to make it easier to market to these individual communities, and to do so by targeting ever more personalised content which, because it is more personalised, is more likely to generate the response that advertisers desire. But the system has spiralled out of control because it rewards the circulation of sensationalist misinformation that appeals to base emotions and promotes an us-vs-them parochialism, all while also encouraging addiction and increasing time spent on the platforms.

Q: Have there been any meaningful attempts to regulate the extraction and commodification of data? What are the dangers in it going unchecked?

In terms of regulation, governments have until recently done very little to prevent or even regulate this. Partly because it took them a long time to understand what was going on, but also because most governments have actually pursued policies of media deregulation, interfering less and less in the “free market” and giving corporations more power to act unhindered. Let’s not forget that governments are often very happy to get access to the vast datasets that commercial corporations are amassing, as for example Edward Snowden revealed a decade ago. Many think that recent EU legislation (the 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), new legislation such as the Digital Services Act and the recently approved AI Act) provides counter-examples, but we have some doubts. The GDPR depends on the mechanism of consent, and our consent is often obtained through market pressures. Meanwhile the newer EU legislation, when it comes fully into force, while it will impose significant inconveniences for Big Tech companies, especially the largest, is not designed to challenge in a fundamental way the trend towards ever more data extraction and the expanding use of AI. Its goal rather is to help data and AI markets work more fairly, which is very different.

Unless we do something to stop its advances, the emerging social order will ensure that there is no living space which has not already been configured so as to optimise data extraction and the wider operation of business logics.

There is no doubt a role for regulation, but it is unlikely ever to be enough, because it does not think in terms of changing how we live, of reimagining a whole interlocking social and economic order that favours corporate over human interests. Unless we do something to stop its advances, the emerging social order will ensure that there is no living space which has not already been configured so as to optimise data extraction and the wider operation of business logics. As such, it will be just the latest stage in the ever-closer relations between colonialism and capitalism.

Q: What are the inequalities or power asymmetries that data exploitation introduces, and how do they connect to or reinforce existing inequalities?

Data colonialism entails a form of data extractivism that has one main purpose: the generation of value in a profoundly unequal and asymmetrical way whose negative impacts are more acutely felt by the traditional victims of colonialism, whether we define them in terms of race, class and gender, or the intersectional of those categories.

In traditional Marxist terms, we think of exploitation and expropriation as something happening to workers in the workplace. In data colonialism, exploitation happens everywhere and all the time

If we think in traditional Marxist terms, we think of exploitation and expropriation as something happening to workers in the workplace. In data colonialism, exploitation happens everywhere and all the time, because we don’t need to be working in order to contribute to this system. We can in fact be doing the opposite of working: relaxing and interacting with friends and family. But the extraction and the tracking are happening nonetheless.

The reason why increasingly fewer areas of life are outside the reach of this kind of exploitation is because the colonial mindset tells us that data, like nature and labour before it, are a cheap resource. Data is said to be abundant, just there for the taking, and without a real owner. In order for it to be processed, it needs to be refined with advanced technologies, just like previous colonial resources. So, our role is merely to produce it and surrender it to corporations, whom we are told are the only ones who can transform it into something useful and productive. The more data we surrender, for instance, the smarter AI can become, and the more capable of solving our problems. This premise is of course deeply flawed, because it is based on an extractivism model, and because it results in an unequal order where a few gain, and most of us lose. But it is a premise that is being installed increasingly into how the spaces of everyday life (from the home to the workplace, from education to agriculture) are being organised.

Q: Taking inspiration from existing movements, what strategies of resistance can citizens mobilise against Big Tech’s commercialised datafication?

In the final chapter of Data Grab, we discuss many examples of these kinds of movements. One such example is Los Deliveristas Unidos, a group of gig food delivery workers, mostly immigrants, who work in New York City. They successfully organised to demand better working conditions and a minimum wage. Not all their demands have been put into action, but their example demonstrates that people can confront platforms and push for reform.

The project of decolonising data must be able to formulate solutions that are not only technological but social, political, regulatory, cultural, scientific and educational.

Examples like this suggest that a decolonial vision of data is already being mobilised, and it requires encompassing not one mode of resistance, but many. The project of decolonising data must be able to formulate solutions that are not only technological but social, political, regulatory, cultural, scientific and educational. And it must be able to connect itself to struggles that seemingly have nothing to do with data, but that in reality are part of the same struggles for justice and dignity. That is why many creative responses to data colonialism are coming from feminist groups, from anti-racist groups, from indigenous groups: we can and must learn from these rich responses. And with the Mexican feminist scholar Paola Ricaurte we have set up a network, the Tierra Común network that aims to do just that.

We are hopeful, that decolonising data can become not a movement that is co-opted by certain parties and individuals for political gain, but a larger, pluriversal, global movement of solidarity where regular human beings can reclaim our digital data and transform it into a tool to act on the world, instead of a tool for corporations to act on us.

Note: This interview gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Read an interview with Nick Couldry about the book, “Are we giving away too much online?” from March 2024 for LSE Research for the World.

Watch a short video, What is data colonialism? with Nick Couldry on LSE’s YouTube channel.

Main image credit: Andrey_Popov on Shutterstock.

Colonialists still rule us all…

Apparently David Marquand died yesterday. He wrote this with which I entirely concur… The evisceration and anti – democratic suppression of local authorities continues apace and although most of us object, the Tories in Devon, for example, entirely agree…... Read more

A Tale of Two Genocides: Namibia’s Stand Against Israeli Aggression

The distance between Gaza and Namibia is measured in the thousands of kilometers. But the historical distance is much closer. This is precisely why Namibia was one of the first countries to take a strong stance against the Israeli genocide in Gaza.

Namibia was colonized by the Germans in 1884, while the British colonized Palestine in the 1920s, handing the territory to the Zionist colonizers in 1948.

Though the ethnic and religious fabric of Palestine and Namibia differ, the historical experiences are similar.

It is easy, however, to assume that the history that unifies many countries in the Global South is only that of Western exploitation and victimization. It is also a history of collective struggle and resistance.

Namibia has been inhabited since prehistoric times. This long-rooted history has allowed Namibians, over thousands of years, to establish a sense of belonging to the land and to one another, something that the Germans did not understand or appreciate.

When the Germans colonized Namibia, giving it the name of ‘German Southwest Africa,’’ they did what all other Western colonialists have done, from Palestine to South Africa to Algeria, to virtually all Global South countries. They attempted to divide the people, exploited their resources and butchered those who resisted.

Although a country with a small population, Namibians resisted their colonizers, resulting in the German decision to simply exterminate the natives, literally killing the majority of the population.

Since the start of the Israeli genocide in Gaza, Namibia answered the call of solidarity with the Palestinians, along with many African and South American countries, including Colombia, Nicaragua, Cuba, South Africa, Brazil, China and many others.

Namibia rejects Germany’s Support of the Genocidal Intent of the Racist Israeli State against Innocent Civilians in Gaza

On Namibian soil, #Germany committed the first genocide of the 20th century in 1904-1908, in which tens of thousands of innocent Namibians died in the most… pic.twitter.com/ZxwWxLv8yt

— Namibian Presidency (@NamPresidency) January 13, 2024

Though intersectionality is a much-celebrated notion in Western academia, no academic theory is needed for oppressed, colonized nations in the Global South to exhibit solidarity with one another.

So when Namibia took a strong stance against Israel’s largest military supporter in Europe – Germany – it did so based on Namibia’s total awareness of its history.

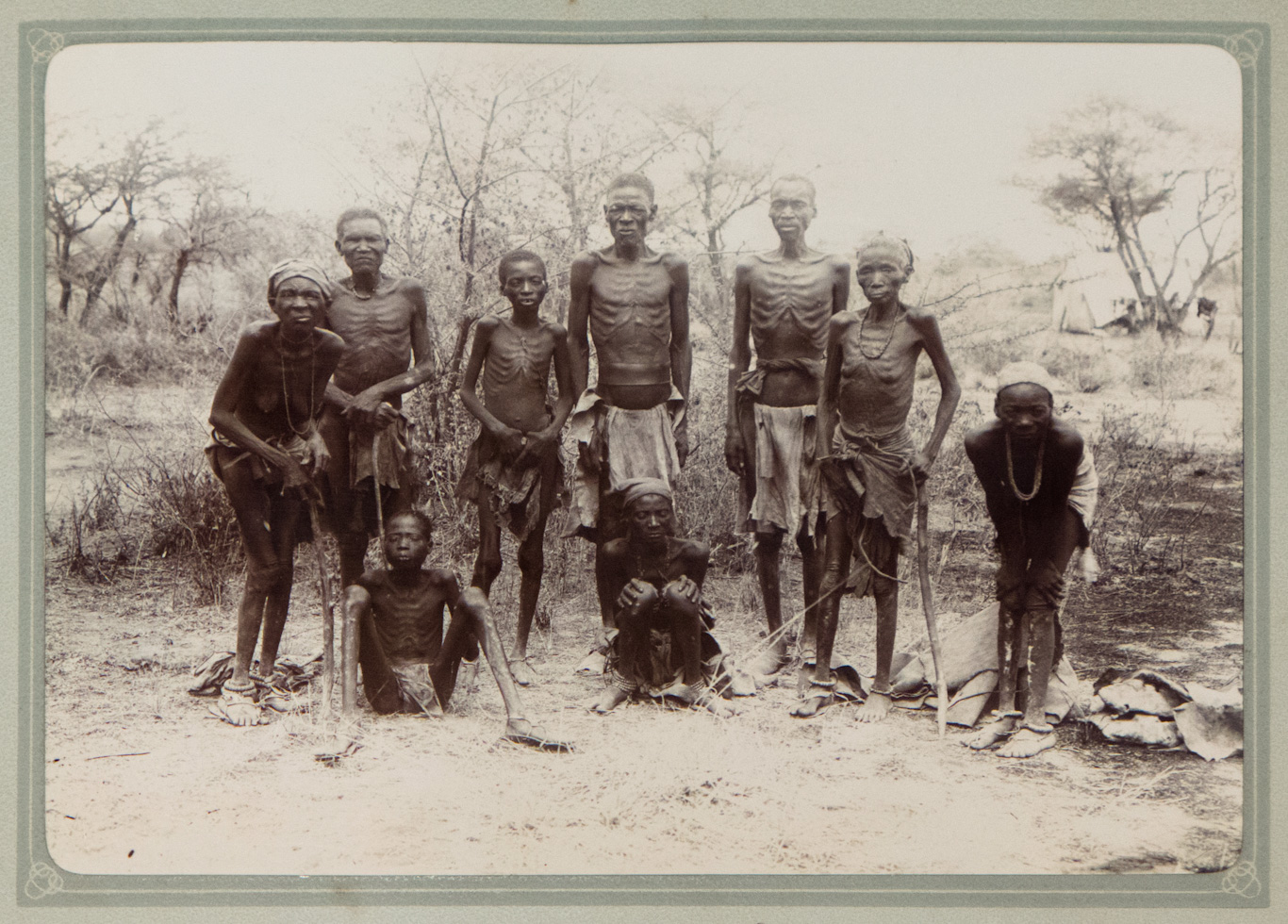

The German genocide of the Nama and Herero people (1904-1907) is known as the “first genocide of the 20th century”. The ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza is the first genocide of the 21st century. The unity between Palestine and Namibia is now cemented through mutual suffering.

However, Namibia did not launch a legal case against Germany at the International Court of Justice (ICJ); it was Nicaragua, a Central American country thousands of miles away from Palestine and Namibia.

The Nicaraguan case accuses Germany of violating the ‘Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.’ It rightly sees Germany as a partner in the ongoing genocide of the Palestinians.

This accusation alone should terrify the German people, in fact, the whole world, as Germany has been affiliated with genocides from its early days as a colonial power. The horrific crime of the Holocaust and other mass killings carried out by the German government against Jews and other minority groups in Europe during WWII is a continuation of other German crimes committed against Africans decades earlier.

The typical analysis of why Germany continues to support Israel is explained based on German guilt over the Holocaust. This explanation, however, is partly illogical and partly erroneous.

It is illogical because if Germany has, indeed, internalized any guilt from its previous mass killings, it would make no sense for Berlin to add yet more guilt by allowing Palestinians to be butchered en masse. If guilt indeed exists, it is not genuine. It is erroneous because it completely overlooks the German genocide in Namibia. It took the German government until 2021 to acknowledge the horrific butchery in that poor African country, ultimately agreeing to pay merely one billion euros in ‘community aid,’ which will be allocated over three decades.

The German government’s support of the Israeli war on Gaza is not motivated by guilt but by a power paradigm that governs the relations among colonial countries. Many countries in the Global South understand this logic very well, thus the growing solidarity with Palestine.

A photo titled “Captured Hereros,” taken circa 1904 by German colonists in Namibia. Photo | German Historical Museum

A photo titled “Captured Hereros,” taken circa 1904 by German colonists in Namibia. Photo | German Historical Museum

The Israeli brutality in Gaza, but also the Palestinian sumud, resilience and resistance, are inspiring the Global South to reclaim its centrality in anti-colonial liberation struggles.

The revolution in the Global South’s outlook—culminating in South Africa’s case at the ICJ and the Nicaraguan lawsuit against Germany—indicates that change is not the outcome of a collective emotional reaction. Instead, it is part and parcel of the shifting relationship between the Global South and the Global North.

Africa has been undergoing a process of geopolitical restructuring for years. The anti-French rebellions in West Africa, demanding true independence from the continent’s former colonial masters, and the intense geopolitical competition involving Russia, China and others are all signs of changing times. And with this rapid rearrangement, a new political discourse and popular rhetoric are emerging, often expressed in the revolutionary language emanating from Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali and others.

But the shift is not happening only on the rhetorical front. The rise of BRICS as a powerful new platform for economic integration between Asia and the rest of the Global South has opened up the possibility of alternatives to Western financial and political institutions.

In 2023, it was revealed that BRICS countries hold 32 percent of the world’s total GDP, compared to 30 percent held by the G7 countries. This has much political value, as four of the five original founders of BRICS are strong and unapologetic supporters of the Palestinians.

While South Africa has been championing the legal front against Israel, Russia and China are battling the US at the UN Security Council to institute a ceasefire. Beijing’s Ambassador to The Hague defended the Palestinian armed struggle as legitimate under international law.

Now that global dynamics are working in favor of Palestinians, it is time for the Palestinian struggle to return to the embrace of the Global South, where shared histories will always serve as a foundation for meaningful solidarity.

Feature photo | Hon. Yvonne Dausab, Minister of Justice of Namibia, joined representatives of over 50 nations in presenting testimony to the International Court of Justice on the legality of the Israeli occupation. Photo | International Court of Justice

Dr. Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of six books. His latest book, co-edited with Ilan Pappé, is ‘Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak Out.’ His other books include ‘My Father Was a Freedom Fighter’ and ‘The Last Earth.’ Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net

The post A Tale of Two Genocides: Namibia’s Stand Against Israeli Aggression appeared first on MintPress News.

It’s the voice of ‘rural nullius’ on ABC’s Jim Crow Country Hour

The proposal to make a constitutional change affecting the nation’s relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—the Voice—was widely reported on mainstream Australian media. However, it went almost completely unreported on during hundreds of editions of the ABC’s midday Country Hour program and morning Regional Reports. During the three-week period before the Voice referendum and the week afterwards, the state editions of Country Hour and the local Regional Reports aired over 1,300 stories across regional Australia, from Broome to Ballarat and from Cairns to Esperance. However, only two episodes of Country Hour—both in Western Australia—included stories on the Voice. This level of reporting was consistent with previous findings on the nature of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation on ABC Rural programs.

Sixty years ago the Australian anthropologist and Boyer lecturer Bill Stanner coined the ageless expression ‘the great Australian silence’ to describe how Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is excluded from public discourse. The segregating-out of stories about the Voice to somewhere else in the ABC is a clear victory for the rural land-owning class, pointing to a healthy feedback loop between ABC program producers and politically powerful settler farmers. ABC Rural’s great silence is all the more egregious given that there are numerous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic systems of production in the rural space that it could be reporting on. There are practices new and old being employed today by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, both locally and in wider economic systems—on homeland estates and settler properties, in rural towns and in the seas where people exercise continuing rights to contribute to their own sustenance. Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economies are inextricably bound up with cultural systems, so when these economic systems are rejected as being inferior there is an implied slur on culture as well. And now they are also rejected as not being ‘agricultural’ enough, and therefore not ‘rural’ enough—not assimilated enough—for inclusion in ABC Rural programs. Their absence perpetuates the terra nullius fallacy that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land use is neither rural nor regional, but exists as some other form of activity situated further down—or not even on—an order in an imagined Darwinian hierarchy of rural land use.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s claims to land and their continuing uses of land conflict with settler farming practices. These claims can include the exercise of rights to enter farming country to conduct various activities. Farmers commonly resist the exercise of rights as an ‘intrusion’ on ‘their property’ as do they resent the duty of care placed on them to protect cultural places. Protection of cultural places for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can include maintaining ecosystems and riverine systems for traditional use, yet in the four-week period studied, the great bulk of stories on the rural programs addressed only settler land uses. Only one story reported on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land and water interests—specifically, an increase in Traditional Owner water allocations in Gippsland.

Examination of all stories aired in the four-week period of this study gives a further indication of how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rural ‘production’ is currently being reported on by ABC Rural programs, and how far it has to go to become influential amidst the din of settler voices. Out of over a thousand stories across Australia, only one reported on an Aboriginal ‘industry’: a large contract which was awarded to an Aboriginal-owned mining ancillary business in the Pilbara, in which a spokesperson commented, with some irony, that he would prefer it if there was no mining on his traditional country.

Western Australia’s Country Hour was the only ABC Rural program that broadcast stories on the Voice in the four-week period of this study. No Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander speakers were reported on as putting forward the case for Yes anywhere in Australia during this period. One story dutifully reported on a procession of four prominent speakers for the No case at the Pastoralists and Graziers Association’s annual convention where Aboriginal activist Warren Mundine, a guest speaker for the No case at the convention, pointed to the social standing and discursive power farmers acquire through agricultural production. A former governor of WA, Malcolm McCusker, also spoke at the convention. His reactionary, assimilationist views appeared to challenge the basis of native title as well as the Voice proposal. The Country Hour reporter introduced and summed up McCusker’s speech as follows: ‘it’s a myth that Aboriginal people don’t currently have a voice in parliament or in government around Australia and he thinks the majority of Aboriginal people aren’t in need of the sort of assistance that the Voice is claiming to offer’. Other speakers reported on were Peter Dutton and Tony Seabrook, the president of the Pastoralists and Graziers Association, and Seabrook was given more time to promote his conspiracy-theorist views about the Voice proposal on another edition of Country Hour on 28 September 2023. The voices of lobby groups and industry associations and their governance matters were reported on, but not the governance potential of the Voice.

Even apart from the Voice issue, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are routinely ignored on ABC Rural programs. Many stories pass the cut as ‘rural news’ even though their connection to Australian agricultural production is tenuous. So even as the Voice was ruled out as ‘rural news’, other stories abounded, supported by an array of arcane cultural messages and symbols: the pioneering fifth-generation farming family; the horse rider; the woman horse rider; bush races; woman in the bush; the struggling farmer, truck driver, fisher, Israeli farmer, Irish farmer and even ‘country singer’. Rodeo news is rural news on Country Hour. A rodeo story emanating from the Northern Territory’s prison regime, desperate for good news stories about Aboriginal people, described Aboriginal prisoners being allowed to participate in the Alice Springs rodeo. It was broadcast six times across several states. Only seven other stories reporting on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander matters were broadcast in the four-week period examined, making up a total of thirteen Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories out of over 1,300 broadcast. The Alice Springs rodeo story made up about half of the Aboriginal and Torres strait Islander content. In comparison, a story about Israeli farmers which focused on how the Israel-Gaza war was ‘taking a terrible toll on agriculture in the south of Israel’ was re-broadcast five times across different programs and locations. Farmers in the south of Israel were granted nearly as much air-time in the four weeks as all the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations across all of Australia.

Listeners will hear of sales of pastoral stations, with comments from vendors, buyers, property agents and conservation groups boosting the property’s social licence, but not from Traditional Owners who have their own native title overlying the properties with complex layers of song lines that are of huge importance to group wellbeing. Their interest goes unrecorded. Instead, stories that explore Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights, governance and society are expected to be covered somewhere else on the ABC, if they’re lucky. It is clearly not in the interests of the powerful—whether roving international capital or settler farmers—for the ABC to interfere with this carefully constructed hegemony by broadcasting knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander law and connection to country.

The battle for control of regional discourse and the institutionalised suppression and segregation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander presence in the rural space bears comparison with ‘Jim Crow’ culture in America. The conservative farmer think-tank the Page Research Centre (‘we work closely with The Nationals’) has sponsored research that recommends controlling how the story of the rural is imagined and told even more tightly by ‘giving Regional Australia a separate but complimentary [sic] ABC Regional organisation, with its own Charter and infrastructure, dedication [sic] to serving Australia’s regions’. Before any change can occur at the ABC, its political and organisational leadership, under pressure to steer an ever more conservative course, would do well to listen more closely to its rural programs with their reek of Jim Crow radio and consider whether they conform to the ABC charter. Among the established leadership there will be those with vested interests who are very comfortable with the existing, segregated view of the rural that is being produced. The settler rural story has been thoroughly naturalised and has been privileging the big end of the city and country towns for a very long time and any hint of change will be staunchly resisted. Regardless of how the Voice referendum was reported on, however, it is long past time that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were represented by ABC Rural programs as a complex living culture with interests that extend beyond one-dimensional and politically unthreatening stories about ‘bush tucker’ or ‘training to be a rodeo rider’.

Still Fighting the Frontier Wars

Brian Burkett, Sep 2023

Taking a thoroughly Orwellian approach, Katter’s Australian Party’s ‘Newspeak’ produces a twisted white supremacist discourse that easily forgets the killing times.

Mongrel Mobs? The Gang Crackdown in Aotearoa

The new National government’s law and order push will destroy gangs’ positive role as family and cultural institutions.

In July 2023 New Zealand’s media reported hundreds of gang members from the notorious Mongrel Mob descending on the small town of Ōpōtiki. Footage from the day reveals leather-jacketed gangsters resplendent in affiliate patches, some with facial tattoos, on motorcycles roaring down the main strip. The Mongrel Mob Barbarians had gathered for a tangi (funeral) of a fallen comrade; that his death had occurred during a stoush with staunch rivals Black Power that included homes torched and shots fired drew widespread media and political attention.

Then Opposition leader and now Prime Minister—Chris Luxon of the conservative National Party—took the opportunity to bolster his ‘tough on gangs’ stance, a position that contributed to his election win the following October. In response to the tangi, his party released a media statement saying the Mongrel Mob had ‘effectively take[n] control of the town’, warning of the ‘grave threat to New Zealand society’ such gangs are said to pose.

Taking aim at his election opponents, he claimed that Labour’s ‘inaction’ on gangs during their incumbency since 2017 had led to a 66 per cent rise in gang membership, stating, ‘alarmingly, gangs are now recruiting around twice as fast as the police’. At odds with Luxon’s moral panic, however, Ōpōtiki mayor David Moore took a more measured approach. ‘It’s become a political football’, he said. ‘I’ve got an eighty-year-old mother who drives around town like nothing has happened; if you walk into any shop they might say it’s been a bit noisy, but that’s about all’.

New Zealand’s gangs have long been fodder for the media and politicians, a convenient embodiment of an ‘other’ on which to blame society’s ills. Yet while criminal activities are carried out by elements in some of New Zealand’s myriad gangs—including drive-by shootings and a lucrative methamphetamine trade—the Ōpōtiki mayor’s relaxed comment reflects a cultural landscape in which gangs are just as much part of New Zealand’s social fabric as the All Blacks.

In the post-Second World War period, New Zealand’s gangs became embedded in predominantly Māori and Pacific Islander communities. They are unique in their multigenerational and familial membership: some of the oldest gangs—such as the Mongrel Mob—can count five generations of membership in some whānau (families). Also unique to New Zealand’s gangs has been the state’s role in the gangs’ early emergence. Punitive child welfare policies directed towards predominantly Māori communities saw many young boys interned in abusive institutions, emerging in their late teens in protective gang clusters inspired by 1950s and 60s American road movies, often minus the motorcycles. The predominance of Māori and Pacific Islander members in gangs, coupled with assimilationist policies, has meant that New Zealand’s gangs have acted as cultural incubators and provided a semblance of whānau in response to such punitive child welfare policies.

Of course, not all Māori and Pacific Islander whānau are allied to gangs, and gang composition also reflects New Zealand’s multicultural demographics, including a cohort of disaffected Pākehā (Europeans). According to a July 2022 parliamentary report, 77 per cent of gang members are Māori, with police reporting in April 2023 a 10 per cent increase in gang membership in under a year, bringing the total number of members to 8875 across thirty-three gangs, as listed in the National Gang List.

Without a nuanced understanding of the history of gang formation and the social and cultural context of gang membership, however, Luxon’s ‘tough on gangs’ rhetoric will do little to address the criminal element that does exist, and may exacerbate the very ‘problem’ of increased gang membership that he hopes to resolve.

Criminals or communities?

In the media release published after the Ōpōtiki tangi, Luxon launched the National Party’s policies for combating what he referred to as the ‘grave threat’ of gangs: the banning of gang insignia, or ‘patches’, in public; police powers to prevent gangs from gathering and communicating; tougher sentences for gang affiliation; and the creation of ‘young offender military academies’.

Criminologist Juan Tauri told this author that the familial nature of gang membership distinguishes New Zealand’s gangs from others around the world and makes preventing gang members from gathering and communicating impossible. ‘One of the key differences [in New Zealand] is the whānau-based nature of the ethnic gangs … A lot of Mongrel Mob chapters are whānau oriented’. He said that in some families this can include up to five generations of gang membership, of the same and other gangs.

Tauri also disputed the government’s statistics on gang members, saying official numbers are inflated because of the inclusion of gang ‘associates’ and that gang members are never removed from the list even if they stop being active in a gang. He even said, ‘I was on the list of associates because I have family in the Mongrel Mob and in Black Power and I had done policy work with them’.

The whānau-based nature of gang membership means that Luxon’s tough on gangs policy can be interpreted as ‘tough on whānau’, a view held by Bonnie Maihi, a PhD student and daughter of a former Black Power rangatira (leader). ‘Tough on crime is tough on families … If you talk about tough on crime, that’s what you are really talking about’. She said that the multigenerational gang experience forms a deep, shared history for some Māori and Pacific Islander families: ‘You don’t want to hear the government say gangs won’t exist anymore. It’s like saying our history and our family won’t exist anymore … That’s part of our whakapapa [genealogy] now. That’s part of who we are. You can’t take that away’. Maihi says that the political rhetoric about gang membership is ‘becoming more linked to being Māori’.

This association of gang membership and Māori ethnicity cements the image of the Māori ‘gangster’ and dangerous colonial ‘other’, only confirming one of the reasons for gangs existing in the first place: Māori peoples’ disconnection from mainstream society, which is intricately related to New Zealand’s history of abusive state-run borstals—largely Māori boys’ homes—which historically fed the early formation of the gangs.

Made by the state

Emerging out of postwar state- and church-run institutions, early gangs such as the Mongrel Mob, the Stormtroopers, King Cobras and Black Power were a social and cultural response to shocking physical, sexual and cultural abuse perpetrated upon predominantly Māori and Pacific Islander children.

After the Second World War, government intervention in Māori communities notably escalated as high urban migration from rural regions saw increased contact with police and child welfare. Thus from the 1940s to the early 1970s, Māori children were about three times as likely as Pākehā children to appear before the courts for offences such as ‘neglect’ or being ‘not under proper control’.i The state’s solution was to send these ‘delinquent’ children to boys’ homes. An estimated 655,000 children were placed in state- or church-run institutions, with more than a third suffering abuse. Māori children are estimated to have been taken into state care at ten times the rate of non-Māori during this period, so that by the late 1970s, approximately one in every fourteen Māori boys and one in every fifty Māori girls was living in a state institution. Pacific Islander children were also overrepresented after migration from Polynesia began in the early 1970s.

It is from these institutions that the early gangs such as the Mongrel Mob emerged, with 80 to 90 per cent of early gang members said to have been in state care. ‘By the early to mid 1960s [Māori] were being heavily criminalised’, confirmed Juan Tauri. ‘It is really through the borstal system that we see the antecedents of the Mongrel Mob and Black Power. The vast majority of those initial members had all gone through the borstal system, and from there to prison’. The abuse inflicted by the state created the conditions for the violence and anti-social behaviour for which many of the gangs would become notorious.

In 2018 Jacinda Ardern’s government established a Royal Commission into institutional abuse. In stark contrast to Luxon’s policy, the Royal Commission sought to engage directly with gang rangatira to better understand the historical underpinnings of gang membership. It was a rare occasion where gang rangatira would meet government representatives to kōrero (talk) as equal participants, not as criminals and outsiders.

The Royal Commission

Fa’afete’ ‘Fete’ Taito is one of those men who journeyed along the pipeline from boys’ home to gang membership. The son of Samoan migrants, Taito grew up in a violent home from which he would run away regularly, until he was interned in Ōwairaka Boys’ Home in Auckland. Here the violence and other forms of abuse would escalate, including forced boxing matches and sexual advances from housemasters. Taito felt that the state took away his Samoan identity, identified as he was simply as a ‘New Zealander’. ‘With a stroke of a pen they took away my identity right there’, he told this author.

The experience of the boys’ home had a profound impact. Leaving it at eighteen, he joined the King Cobras, where he found belonging and re-discovered his culture: ‘joining a gang wasn’t a negative to me at all … The majority of them were Pacific Islanders. And that was me too. The positive about being there is you have a sense of belonging. The King Cobras gave that to me because there were lots of Samoans there’. But along with the positive sense of belonging came a dark side too: violence and crime, which resulted in ten years of methamphetamine addiction and eight years of prison.

No longer a gang member, Taito now works as a liaison between the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care and gang rangatira documenting the abuses suffered by gang members.

The Royal Commission hui (meeting) held in February 2023 was instigated by Mongrel Mob leader Sonny Fatupaito, a controversial figure in New Zealand’s gang landscape. The 67-year-old served six years in prison for manslaughter and recently saw his second-in-command locked up for methamphetamine trafficking. Yet his chapter of the Mongrel Mob—Mongrel Mob Kingdom—also runs trauma therapy sessions in Māori maraes (meeting places) and stood guard in front of a local mosque after the Christchurch terrorist attack. It also spearheaded a vaccination program during the COVID pandemic, approved by former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern.

‘I’m not here to entertain or to say that “we’re different” or “we are trying to be good people”’, he told this author.

My whole focus is to heal these men to make sure they are as best they can be and to push them back to their maraes [traditional meeting places] because state care—they took all that away. They were dealt with morals and principles that weren’t theirs. So you’ve got to decolonise the mindset.

Contrary to Luxon’s approach of excluding and isolating gangs—a failed approach of successive governments—Fatupaito instead advocates increased engagement, saying the Royal Commission hui should be ‘just the beginning’. For him, ‘To have something you’ve never had before, sometimes you’ve got to do something you’ve never done before’.

Cultural incubators

Nayda Te Rangi knows what it’s like on the receiving end of a traumatised gang member. She joined the gang scene in Wellington in the 1970s and recalls experiences of acute violence against women and instances of sexual assault. ‘You always had your alarm on, if you thought something was going to happen, like rape or blocking [gang rape ] … From the time that gangs were created, women were seen as a hunk of meat’.

Te Rangi would eventually form Aroha Trust, a women’s group assisting underprivileged women, predominantly from gangs, and confronting gang rangatira about their behaviour towards women. While not excusing the behaviour of the older generation of gang members, Te Rangi understands the abuse those same men had suffered as children in the institutions: ‘They’ve been raped as well. And not just once or twice, but all the time they were in [state] care … What that would do to a person. These are broken men’.

Te Rangi says the government needs to understand not only the traumatic history of gang members but also the role gangs have played as resistors against assimilation. ‘A lot of those who went through state care don’t have a connection to their whānau [family], their hapu [clan] or their iwi [tribe]’, she said. ‘They see their kaupapa whānau [extended family in a gang] in a positive light because that’s all they know’. Like Juan Tauri’s, Te Rangi’s family was part of the postwar urban migration of Māori, and along with increased contact with the authorities, assimilation had an impact on her engagement with Te Reo (Māori language) and tikanga (culture). ‘I would hear my parents speaking Māori to each other but we were never taught’, she said:

This was the Pākehā world [and speaking Māori] wouldn’t get you anywhere. We all grew up hearing that … I was really surprised when I found out from long-time friends that they were fluent Māori language speakers. But they just wouldn’t kōrero Te Reo Māori because you don’t want people to think you’re a dumb-dumb black Māori from the country, so you didn’t.

Like Taito, she says that the gangs provided an opportunity to reconnect with her culture that the mainstream didn’t at the time, with lasting positive effects:

If you go to a tangi, of say a Mongrel Mob member, and you’ve got lots of other gangs there—whether they are Pasifika or Māori—and the Pasifika one will get up and speak their language, which is really respectful, and is wonderful to hear and see … There’s no longer that shame of being Māori or Pasifika. We are not embarrassed to speak Te Reo like how we used to be. When you speak Te Reo Māori it changes you. This is what tikanga [Māori culture] does—it gives everybody their own respect and mana [spirit].

* * *

The journey from state care to gang membership continues to be an oft-travelled route for many Māori and Pasifika today. While making up only 15 per cent of the country’s population, Māori make up 52 per cent of the prison population, continue to be overrepresented in child welfare and are more likely to live beneath the poverty line. Pacific Islanders—who began migrating in the 1970’s from countries such as Samoa, Tonga and the Cook Islands—are also overrepresented in the same statistics.

While the current child welfare agency Oranga Tamariki has recently been investigated for historical abuse, and while young people are likely not joining gangs in the numbers Luxon suggests, youth crime remains a persistent issue. Yet Luxon’s ‘solution’—forcing young people, who will largely be Māori and Pasifika, into ‘military-style academies’ will not be the answer. The proposal has already been met with disgust by the men who were previously forced into similar regimes in the borstals and who were subsequently abused, as they testified to the Royal Commission. The tough on gangs approach demonstrates a short-sightedness that will likely exacerbate the gang’s place as society’s ‘other’ and serve to perpetuate anti-social behaviour.

The alternative is for the government to take responsibility for the state’s role in gang formation. Providing trauma-informed justice approaches and reforming current child welfare practices would alleviate the historical burden of state abuse and help close the pipeline of state care to prison and gang membership. Gangs should be engaged as legitimate members of the community—as in the case of the Royal Commission—and the mana that gang rangatira hold in their communities acknowledged. This is the starting point for dissuading disaffected young people from entering the criminal world, whether in gangs or not.

One example of supporting the existing gang leadership in affiliated communities has been the highly successful Mongrel Mob-run methamphetamine addiction program Kahukura, which has seen a third of participants remain drug-free since completing the eight-week marae-based program. Harry Tam, an affiliate of the Notorious Chapter of the Mongrel Mob and son of Chinese migrants, has worked with what he calls ‘hard to reach’ communities for decades and was instrumental in establishing Kahukura. He believes it is vital for government to understand that gangs are communities, and not always criminal, and for the gang community to itself be ready to change. ‘You can’t say: “that’s what the policy should be”. What we should say is: “policy should be based on supporting communities that are ready”’.

By contrast, Luxon’s policy is counterproductive. It is impossible to police and creates the perception that it is an attack on Māori and Pacific Islander communities. It will only exacerbate the ‘them and us’ sentiment seemingly on the increase in contemporary New Zealand. Luxon is unlikely to reverse his position, to which Juan Tauri says, ‘it’s just a “vote winner”’, and that Luxon must know ‘deep down that is not going to work’. For him, ‘the criminalisation of gangs stifles any meaningful response [from government]…[For policy to] work, it has to be a social development approach’.

Or, as Mongrel Mob Kingdom rangatira Sonny Fatupaito told this author: ‘To have something you’ve never had before, sometimes you’ve got to do something you’ve never done before’.

i Bronwyn Dalley, ‘Moving Out of the Realm of Myth’, New Zealand Journal of History, 32(2), 1998, pp 189–207.

Toward an Intellectual History of Genocide in Gaza

The destruction of Gaza begins with ideas.

The US Should Only Support a Multiethnic, Nonsectarian Israel

Whether or not it sways Netanyahu, we should certainly withhold military funding now and make our support contingent on clearly stated humanitarian objectives and an ultimate governing framework that conforms to our ideas of justice....

Why Antisemitism is an Insufficient (and Risky) Explanation for Hamas’s October 7 Attack on Israel

Amidst a recent layover, my phone pinged to indicate I’d been “mentioned” on Twitter, which...

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace – review

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox brings together scholars to analyse the failure of Afghan state-building, the Taliban’s resurgence and the country’s future. Anil Kaan Yildirim finds the book a valuable resource for understanding challenges the country faces, including women’s rights, the drugs economies and human trafficking and exploitation. However, he objects to the inclusion of a chapter which makes a geographically deterministic appraisal of Afghanistan’s governance.

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace. Michael Cox (ed.). LSE Press. 2022.

This book is available Open Access here.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country. However, in the case of Afghanistan, as argued by Michael Callen and Shahim Kabuli in Chapter Three, the de facto power structure did not align with the de jure systems of institutions. Excluding the Taliban from political discussions, adopting a fundamentally flawed and exclusionary electoral system, and employing a centralised presidential system which did not correspond to Afghan “diversity and reality” have been the “three sins” of the Afghanistan project. Along with these mistakes, the authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China that tried to attract the power-holders of the country. This powerful essay points out the three sins in the creation of the structure and other dynamics that destabilised the country. Thus, the state-building project collapsed not because Afghanistan was unsuited to democracy, but because of a combination of many different mistakes.

The authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China

The role of women in the Afghan state-building effort is highly contested among different power holders, the international community, and the Taliban. Writing in this context in Chapter Six, Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists. The highly masculinised country following many years of different wars created a challenging political and social area for women. Therefore, all changes in the political sphere resulted in a change in the lives of women.

Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists.

As an internationalised state-building project, Afghanistan has challenged international institutions and norms. Devika Hovell and Michelle Hughes examine the US and its allies’ interpretation and application of international law in military intervention in Afghanistan. With discussion of several steps and actors of the intervention, they demonstrate how this operation stretched the definitions of self-defence, credibility, legal justification, and authority within international realm.

The book explores several other key problems in the country. These include Thi Hoang’s chapter on human trafficking problems such as forced labour, organ trafficking and sexual exploitation; John Collins, Shehryar Fazli and Ian Tennant’s chapter on the past and future of the international drug trade in Afghanistan; Leslie Vinjamuri on the future of the US’s global politics after its withdrawal from the state; and Feng Zhang on the Chinese government’s policy on Afghanistan.

The essays mentioned above demonstrate what happened, what could have been evaded and what the future holds for Afghanistan. However, the essay, “Afghanistan: Learning from History?” by Rodric Braithwaite is a questionable inclusion in the volume. By emphasising geographical determinism, this piece a problematic perspective on Afghanistan. The essay argues that the failure of the West’s state-building project was down to the “wild” character of Afghan governance historically, which he deems “… a combination of bribery, ruthlessness towards the weak, compromise with the powerful, keeping the key factions in balance and leaving well alone … (17)” or “… nepotism, compromise, bribery, and occasional threat” (26-27). This perspective paints a false image of how Afghan history is characterised by unethical, even brutal methods of governance. Also in this essay are many problematic cultural claims such as “… Afghans are good at dying for their country … (18).”

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative, which is reflected in and supported by the postcolonial term for Afghanistan: the “graveyard of empires”. While many different tribes, states, and empires have successfully existed in the country, Western colonial armies’ defeats and recent state-building failures should not misrepresent the country as a savage place in need of taming. Rather, as the other essays in the book argue, research on these failures should examine the West’s role in precipitating them.

Not only does this piece disrespect the scholarship (including other authors of the book) by asserting the ontological ungovernability of the country, but its deterministic stance also disregards the thousands of lives lost in the struggle to contribute to Afghan life those who believed that the future is not destined by the past but can be built today. Additionally, using only three references (with one being the author’s own book), referring to the US as “America”, random usage of different terms and not providing the source of a quotation are all quite problematic for a lessons-learned-from-history essay.

Beyond the limitations of the essay in terms of how it frames the past, what is more damaging is the creation of a false image of Afghanistan for future researchers and policymakers. For the points mentioned above, including the false narrative of ‘graveyard of empires’, Nivi Manchanda’s Imagining Afghanistan: The History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (2020) is worth consulting for in-depth insight into the colonial knowledge production system and its problematic portrayal of Afghanistan.

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation. For practitioners, policymakers, and scholars seeking a broad perspective on state-building problems, policy limitations and relevant research areas in Afghanistan, this collection is a useful resource.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Trent Inness on Shutterstock.