Development

Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences – review

In Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences, Dirk-Jan Koch examines the unintended effects of development efforts, covering issues such as conflicts, migration, inequality and environmental degradation. Ruerd Ruben finds the book an original and detailed analysis that can help development policymakers and practitioners to better anticipate these consequences and build adaptive programmes.

Foreign Aid and Its Unintended Consequences. Dirk-Jan Koch. Routledge. 2023.

Dirk-Jan Koch’s Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences offers a rich discussion on the unintended consequences of development efforts, including effects on conflicts, migration and inequality and changes in commodity prices, human behaviour, institutions and environmental degradation. The book explains how different perceptions of donors and recipients lead to quite opposite strategies (eg, for managing the Haiti earthquake), whereas in other settings aid programmes can even intensify local conflicts or spur deforestation.

Dirk-Jan Koch’s Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences offers a rich discussion on the unintended consequences of development efforts, including effects on conflicts, migration and inequality and changes in commodity prices, human behaviour, institutions and environmental degradation. The book explains how different perceptions of donors and recipients lead to quite opposite strategies (eg, for managing the Haiti earthquake), whereas in other settings aid programmes can even intensify local conflicts or spur deforestation.

Koch devotes due attention to the aggregate impact of development activities through so-called backlash effects, negative spillovers and positive ripple effects.

Koch devotes due attention to the aggregate impact of development activities through so-called backlash effects, negative spillovers and positive ripple effects. Many of these effects also occur in Western countries, where they are commonly labelled as crowding-in and -out, linkages and leakages, and substitution effects. Each chapter includes real-life examples (mostly cases from sub-Saharan Africa), ranging from due diligence legislation on conflict minerals in DR Congo to the experiences of the author’s parents with the Fairtrade shop in the tiny Dutch village of Achterveld.

Koch consistently argues that the analysis of unintended effects is helpful to unravel the complexities of development cooperation and enables better identification of incentives that allow for more adaptive planning. This is a welcome contribution, since it provides a common language for better communication between development agents.

Everyone involved in development programmes is invited by this book to reflect on their own experiences with unintended consequences. I still remember the shock when an external review of a large integrated rural development programme in Southern Nicaragua revealed that most funds were spent at the local gasoline station and car repair workshop for maintenance of the project vehicles. My original enthusiasm for Fairtrade certification of coffee and cocoa cooperatives was substantially reduced when I became aware that price support enabled farmers to maintain their income with less production and therefore increased inequality within rural communities.

Koch consistently shows that it is important and possible to disentangle each of these possible or likely side effects and to act to combat them.

The systematic overview of unintended consequences of foreign aid gives an initial impression that development cooperation is a system beyond repair. This is, however, far from the truth. Koch consistently shows that it is important and possible to disentangle each of these possible or likely side effects and to act to combat them. That requires an open mind and thorough knowledge of responses by different types of agents and institutions.

The analysis falls short, however, in showing that several types of unintended consequences are likely to interact (such as price and marginalisation effects, or conflict and migration effects). Other consequences may partially overlap or perhaps compensate for each other. Moreover, there is likely to be a certain ”hierarchy” in the underlying mechanisms, where behavioural effects, governance effects and price effects crowd out several other consequences. In addition, a further analysis of the development context and the influence of norms and values might be helpful to better understand why certain effects occur, or not.

There is likely to be a certain ‘hierarchy’ in the underlying mechanisms, where behavioural effects, governance effects and price effects crowd out several other consequences

Koch argues that unintended consequences are frequently overlooked due to “linear thinking” in international development. He probably refers to the dominance of logical frameworks in traditional development planning and the recent requirement for presenting a Theory of Change with different impact pathways for development programmes. Since links and feedback loops between activities are already widely acknowledged, Koch seems to merge “linearity” with “causality”. For responsible development policies and programmes, we need better insight into the cause-effect relationship, recognising that differentiated outcomes may occur and that side effects are likely to be registered.

The absence of linear response mechanisms has been part of development thinking since its foundation by development economist and Nobel-prize winner Jan Tinbergen. His work (and my PhD thesis) heavily relied on linear programming, which is still considered as an extremely useful approach for showing that an intervention can generate multiple outcomes and that policymakers need some insights into alternative scenarios before they start to act. Impact analysis through different (quantitative and qualitative) methods digs deeper into the adaptive behaviour of development agents in response to a wide variety of incentives (ranging from financial support and legal rules to knowledge diffusion and information exchange). Our attention should be focused on understanding how non-linearity as occasioned by the involvement of multiple agents with different interests (and power) in development programmes leads to multiple – and sometimes opposing – outcomes from interventions.

Our attention should be focused on understanding how non-linearity […] in development programmes leads to multiple – and sometimes opposing – outcomes from interventions.

Koch’s analysis is based on a wide variety of case studies and testimonies, enriched with secondary research on the gender effects of microfinance, the occurrence of exchange rate disturbances (Dutch Disease), and the effectiveness of incentives to encourage natural resource conservation (Payments for Ecosystem Services). In a few cases, it makes use of more systematic impact reviews made by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) and Campbell Collaboration. Information about the size and relative importance of the unintended consequences is notably absent.

The reliance on illustrative case studies and dense description challenges the academic rigor of the book. It may hinder our understanding about the underlying causes and mechanisms behind these effects: are they generated by the development intervention themselves, or are they due to the context in which the programme is implemented, or the types of stakeholders involved in its implementation? A more comparative approach could be helpful to better understand, for instance, why microfinance was accompanied by an increase in domestic violence in certain parts of India, but not in others. Comparing different ways of designing and organising microfinance would provide clearer insights into the causes of variation in outcomes.

Opening up for such an interactive engagement with development activities asks for an institutional re-design of international development cooperation, permitting projects with a substantially longer duration (eight to ten years), closing the gap between policy and practice and accepting a political commitment for learning from mistakes. Moreover, dealing with unintended consequences requires that far more aid is channelled through embassies and local organisations that have direct insights into local possibilities and needs.

Social and community service programmes for basic education and primary healthcare tend to deliver the most tangible positive effects on incomes, nutrition, behaviour, women’s participation and income distribution.

Furthermore, focusing on adaptive planning and learning trajectories may also imply that policy priorities for foreign aid need to change. Social and community service programmes for basic education and primary healthcare tend to deliver the most tangible positive effects on incomes, nutrition, behaviour, women’s participation and income distribution. The development record of programmes for trade promotion is far more doubtful and still heavily relies on (unproven) trickle-down reasoning. Particular attention should be given to budget support and cash transfers as aid modalities with the least strings attached that show a high impact on critical poverty indicators. Contrary to these findings, several years ago the Dutch parliament stopped budget support and eliminated primary education as a key policy priority.

While the author concludes by focusing on the need to act on side effects and further professionalisation of international development programmes, more concrete leverage points could be identified. First, many of the registered effects tend to be related to cross-cutting structural differences in resources and voice, and therefore programmes that start with improving asset ownership and women’s empowerment are likely to yield simultaneous changes in different areas. Second, a stronger focus on systems analysis (beyond complexity theory) can be helpful to identify inherent conflicts and tensions in development programmes that could be the subject of political negotiation. Unravelling potential trade-offs then becomes a key component of development planning. Third, more space could have been devoted to the role of experiments in the practice of development cooperation. Policymakers expect a high level of certainty and face difficulties to become engaged in more adaptive programming. Accepting deliberate risk-taking may be helpful to improve aid effectiveness.

Policymakers expect a high level of certainty and face difficulties to become engaged in more adaptive programming. Accepting deliberate risk-taking may be helpful to improve aid effectiveness.

These reservations aside, Foreign Aid and its Unintended Consequences is a welcome and original contribution to the debate on development effectiveness. Koch offers a systematic conceptual and empirical analysis of ten types of unintended effects from international development activities, and its recommendations on how these effects can be tackled in practice will be useful for policymakers, practitioners and evaluators.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Jen Watson on Shutterstock.

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace – review

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox brings together scholars to analyse the failure of Afghan state-building, the Taliban’s resurgence and the country’s future. Anil Kaan Yildirim finds the book a valuable resource for understanding challenges the country faces, including women’s rights, the drugs economies and human trafficking and exploitation. However, he objects to the inclusion of a chapter which makes a geographically deterministic appraisal of Afghanistan’s governance.

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace. Michael Cox (ed.). LSE Press. 2022.

This book is available Open Access here.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country. However, in the case of Afghanistan, as argued by Michael Callen and Shahim Kabuli in Chapter Three, the de facto power structure did not align with the de jure systems of institutions. Excluding the Taliban from political discussions, adopting a fundamentally flawed and exclusionary electoral system, and employing a centralised presidential system which did not correspond to Afghan “diversity and reality” have been the “three sins” of the Afghanistan project. Along with these mistakes, the authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China that tried to attract the power-holders of the country. This powerful essay points out the three sins in the creation of the structure and other dynamics that destabilised the country. Thus, the state-building project collapsed not because Afghanistan was unsuited to democracy, but because of a combination of many different mistakes.

The authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China

The role of women in the Afghan state-building effort is highly contested among different power holders, the international community, and the Taliban. Writing in this context in Chapter Six, Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists. The highly masculinised country following many years of different wars created a challenging political and social area for women. Therefore, all changes in the political sphere resulted in a change in the lives of women.

Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists.

As an internationalised state-building project, Afghanistan has challenged international institutions and norms. Devika Hovell and Michelle Hughes examine the US and its allies’ interpretation and application of international law in military intervention in Afghanistan. With discussion of several steps and actors of the intervention, they demonstrate how this operation stretched the definitions of self-defence, credibility, legal justification, and authority within international realm.

The book explores several other key problems in the country. These include Thi Hoang’s chapter on human trafficking problems such as forced labour, organ trafficking and sexual exploitation; John Collins, Shehryar Fazli and Ian Tennant’s chapter on the past and future of the international drug trade in Afghanistan; Leslie Vinjamuri on the future of the US’s global politics after its withdrawal from the state; and Feng Zhang on the Chinese government’s policy on Afghanistan.

The essays mentioned above demonstrate what happened, what could have been evaded and what the future holds for Afghanistan. However, the essay, “Afghanistan: Learning from History?” by Rodric Braithwaite is a questionable inclusion in the volume. By emphasising geographical determinism, this piece a problematic perspective on Afghanistan. The essay argues that the failure of the West’s state-building project was down to the “wild” character of Afghan governance historically, which he deems “… a combination of bribery, ruthlessness towards the weak, compromise with the powerful, keeping the key factions in balance and leaving well alone … (17)” or “… nepotism, compromise, bribery, and occasional threat” (26-27). This perspective paints a false image of how Afghan history is characterised by unethical, even brutal methods of governance. Also in this essay are many problematic cultural claims such as “… Afghans are good at dying for their country … (18).”

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative, which is reflected in and supported by the postcolonial term for Afghanistan: the “graveyard of empires”. While many different tribes, states, and empires have successfully existed in the country, Western colonial armies’ defeats and recent state-building failures should not misrepresent the country as a savage place in need of taming. Rather, as the other essays in the book argue, research on these failures should examine the West’s role in precipitating them.

Not only does this piece disrespect the scholarship (including other authors of the book) by asserting the ontological ungovernability of the country, but its deterministic stance also disregards the thousands of lives lost in the struggle to contribute to Afghan life those who believed that the future is not destined by the past but can be built today. Additionally, using only three references (with one being the author’s own book), referring to the US as “America”, random usage of different terms and not providing the source of a quotation are all quite problematic for a lessons-learned-from-history essay.

Beyond the limitations of the essay in terms of how it frames the past, what is more damaging is the creation of a false image of Afghanistan for future researchers and policymakers. For the points mentioned above, including the false narrative of ‘graveyard of empires’, Nivi Manchanda’s Imagining Afghanistan: The History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (2020) is worth consulting for in-depth insight into the colonial knowledge production system and its problematic portrayal of Afghanistan.

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation. For practitioners, policymakers, and scholars seeking a broad perspective on state-building problems, policy limitations and relevant research areas in Afghanistan, this collection is a useful resource.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Trent Inness on Shutterstock.

Spiritual Contestations: The Violence of Peace in South Sudan – review

In Spiritual Contestations: The Violence of Peace in South Sudan, Naomi Pendle dissects the interactions between Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities amid national and international peacebuilding efforts, exploring the role of spiritual culture and belief in these processes. Based on extensive ethnographic and historical research, the book offers valuable insights for scholars and policymakers in conflict management and peace-building, writes Nadir A. Nasidi.

Spiritual Contestations: The Violence of Peace in South Sudan. Religion in Transforming Africa Series, Vol. Number: 12. Naomi Ruth Pendle. James Currey. 2023.

The history of South Sudan includes a series of protracted conflicts and wars, which have attracted the attention of many researchers covering their socio-economic and political dimensions. Following in this vein, Pendle’s Spiritual Contestations explores the interactions between Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities within the context of national and international peace-making processes. This also includes the role of the clergy and traditional rulers in such processes, which is complicated by politics, sentiments, and the urge to profit from the South Sudan’s protracted conflicts. Pendle also assesses the experiences of ordinary South Sudanese people in peace-making, including their everyday peace-making meetings. The book is divided into three sections and 14 engaging chapters based on the author’s ethnographic and historical research conducted between 2012 and 2022 among the Nuer- and Dinka-speaking peoples.

The history of South Sudan includes a series of protracted conflicts and wars, which have attracted the attention of many researchers covering their socio-economic and political dimensions. Following in this vein, Pendle’s Spiritual Contestations explores the interactions between Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities within the context of national and international peace-making processes. This also includes the role of the clergy and traditional rulers in such processes, which is complicated by politics, sentiments, and the urge to profit from the South Sudan’s protracted conflicts. Pendle also assesses the experiences of ordinary South Sudanese people in peace-making, including their everyday peace-making meetings. The book is divided into three sections and 14 engaging chapters based on the author’s ethnographic and historical research conducted between 2012 and 2022 among the Nuer- and Dinka-speaking peoples.

Pendle’s Spiritual Contestations explores the interactions between Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities within the context of national and international peace-making processes

Chapter one describes the historical evolution of the hakuma (an Arabic-derived, South Sudanese term for government) in the 19th century and the physical violence which South Sudan has experienced through its mercantile and colonial history, as well as many years of war that influenced contemporary peace-making. It also shows how the hakuma claimed “divine” powers (as a result of god-like rights the government arrogated to itself). Chapters two, three, four and five discuss the contemporary making of war and peace, oppositions to the Sudan government’s development agenda, the 1960s and 1972 Addis Ababa Peace Agreement and South Sudan’s 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement. These chapters also examine the Wunlit Peace Meeting, which was a classic example of what the author calls “the ‘local turn’ in peace-making whereby international actors championed ‘local’ forms of peace-making” (35-119).

Chapter seven largely focuses on the escalation of violence in Warrap State as a result of having an indigenous hakuma alongside ever-evolving ideas of land, property, resources, and cattle ownership. Chapters seven to fourteen then focus on the proliferation of peace meetings in Gogrial and the cosmological crisis brought by the years of war (which involves the disruptions or perceived threats to cosmic order and by overarching beliefs about the universe held by the Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities), a crisis which was met with a proliferation of prophets. This section also covers wars in South Sudan since 2013, the prevalence of revenge in giving meaning to armed conflicts, the post-2013 power of the Nuer prophets, the post-2013 era in Warrap State, and the role of the church in South Sudan’s peacekeeping through the activities of Dinka priests who are popularly known as the baany e biith.

Although the title of the book appears oxymoronic, the author argues that peace remains violent when understood in a context wherein the methods employed to establish or foster peace involve force, suppression, and coercion

Although the title of the book appears oxymoronic, the author argues that peace remains violent when understood in a context wherein the methods employed to establish or foster peace involve force, suppression, and coercion. This is especially true in the context of South Sudan’s “unsettled cosmic polity”; a polity characterised by periods of questioning, restructuring or conflict in response to perceived disruptions of cosmic order and balance, which further push the boundaries of contemporary discourse on the meaning and conceptualisation of peace and peace-making (179-189).

The author further explains how […] religious connotations are used to contest the moral logic of government, particularly in the rural areas of South Sudan

Pendle bases her arguments on the “eclectic divine” and religious influences among communities located around the Bilnyang River system. The author further explains how these religious connotations are used to contest the moral logic of government, particularly in the rural areas of South Sudan. Through this means, the author clarifies how religion and religious assertions shape the peoples’ social and political life. This includes issues such as spiritual and moral contestations, as well as the making and unmaking of norms within the “cultural archive” (including traditional, economic and historical recollections) that reshape the violence of peace, feuds, and its associated political economies. She advances this argument in her study of conflicts over natural resources and cultural rights that are understood as cosmological occurrences by the people of South Sudan, the meanings of war and peace, and the assertion of power within these events.

Pendle states that to understand the real politics and violence of peace-making, one must also understand ‘how peace-making interacts with and reshapes power not only in everyday politics’, but also ‘in cosmic polities’

Pendle states that to understand the real politics and violence of peace-making, one must also understand “how peace-making interacts with and reshapes power not only in everyday politics”, but also “in cosmic polities” (75-99). Looking at the nature of human societies, she concludes that they are largely hierarchical, mostly located within the purview of a cosmic polity that is populated by “beings of human attributes and metahuman powers who govern the people’s fate” (7).

Basing her arguments on Graeber and Shalins’ research, Pendle observes that South Sudanese society’s secular governments and self-arrogating divine powers can pass for a cosmic polity. It is within this context that the South Sudanese Arabic term for government, ‘hakuma’ operates; the term refers not only to government, but to a broad socio-political sphere including foreign traders and slavers.

Pendle also documents the various ways in which South Sudanese people use cultural symbols, rituals, norms, and values, as well as theology, to contest ‘predatory power and to make peace’

Pendle also documents the various ways in which South Sudanese people use cultural symbols, rituals, norms, and values, as well as theology, to contest “predatory power and to make peace” (75). Examples include the Dinka use of leopard skin (which is used for conflict resolution between two warring factions), cultural diplomacy through festivals, as well as the ceremonial blessings of cattle as a symbol of wealth.

The book is not without flaws. The author often oscillates between the use of ordinal and cardinal numbers when a chapter is mentioned Even if this is done for convenience, it is at the expense of chronology and consistency. Although written in plain and straight-to-the-point language, the author’s use of compound-complex sentences throughout the book makes it difficult for readers to comprehend easily.

Considering the ongoing conflicts and wars in and around the South Sudan region, Pendle’s Spiritual Contestations is a timely work. Using a close analysis, the author provides incisive insights into the changing nature of wars and conflicts, as well as the violence of peace among the Nuer- and Dinka-speaking communities. The book is a significant resource for scholars in the field of conflict management and peace-building, international organisations, policymakers and anyone interested in considering the interplay of religion, governance, tradition, peace-making, and conflict management.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Richard Juilliart on Shutterstock.

When Disasters Come Home: Making and Manipulating Emergencies In The West – review

In When Disasters Come Home: Making and Manipulating Emergencies In The West, David Keen considers how powers in the Global North exploit, or even manufacture, disasters in the Global South for political or economic gain. Though taking issue with Keen’s engagement with psychoanalysis, Daniele-Hadi Irandoost finds the book an insightful exploration of the global power dynamics involved in disasters and their far-reaching repercussions.

When Disasters Come Home: Making and Manipulating Emergencies In The West. David Keen. Polity. 2023.

In When Disasters Come Home: Making and Manipulating Emergencies In The West anthropological writer David Keen attempts to show how disasters are exploited for political and economic gain. A disaster, as defined by Keen, is “a serious problem occurring over a short or long period of time that causes widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss”. Keen’s analysis deals with two types of disaster in the Global North. The so-called “sudden” or “dramatic” disasters are caused by stark terrorism (eg, the 9/11 attacks), natural causes (Hurricane Katrina), financial and economic recessions (crash of 2007–8), migration crises (Calais), Covid-19, and the war in Ukraine.

In When Disasters Come Home: Making and Manipulating Emergencies In The West anthropological writer David Keen attempts to show how disasters are exploited for political and economic gain. A disaster, as defined by Keen, is “a serious problem occurring over a short or long period of time that causes widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss”. Keen’s analysis deals with two types of disaster in the Global North. The so-called “sudden” or “dramatic” disasters are caused by stark terrorism (eg, the 9/11 attacks), natural causes (Hurricane Katrina), financial and economic recessions (crash of 2007–8), migration crises (Calais), Covid-19, and the war in Ukraine.

Keen attempts to show how disasters are exploited for political and economic gain.

On the other hand, “extended” or “underlying” disasters derive from long-smouldering conditions of economic disparity (eg, globalisation and inequality), considerable changes in climate (deficiencies in the domestic infrastructure), as well as political fragmentation (erosion of democratic norms, etc).

Colonial historiography assumed that disasters were usually confined to the Global South. Incidentally, in his investigative research in the Global South, especially in Sudan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Keen discovered that the politics of that world were disposed to deliberately make, manipulate and legitimise “famines, wars and other disasters”. This state of affairs enabled certain beneficiary actors to extract political, military and economic benefits.

In his investigative research in the Global South, especially in Sudan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Keen discovered that the politics of that world were disposed to deliberately make, manipulate and legitimise famines, wars and other disasters

Here, Keen sounds a note of warning. Democracies provide only a fragile protection against disasters, and for six reasons (according to examples across the globe): disasters might be deemed “acceptable”, vulnerable groups do not always have the “political muscle” to guard against disasters, opportunists may seek to maximise profit through the suffering of certain groups, “elected politicians” may “distort” information about a disaster, democracies “may give false reassurance in terms of the apparent immunity to disaster” (emphasis in original), and, finally, a democracy may itself erode over time.

In theorising disasters, Keen endeavours to advance beyond the traditional distinction between the Global North and the Global South.

In theorising disasters, Keen endeavours to advance beyond the traditional distinction between the Global North and the Global South. His purpose is to show that, in the Western world, disasters have “come home to roost”, that the violence of “far away” countries (“whether in the contemporary era or as part of historical colonialism”) has found its way back into the Global North in the form of “various kinds of blowback”.

These “boomerang effects”, to use Keen’s words, “take a heavy toll on Western politics and society” when they are “incorporated into a renewed politics of intolerance” (“internal colonialism”). In particular, Keen says that, in the Global North, we find there is an increasing drive for security by “allocating additional resources for the military, building walls, and bolstering abusive governments that offer to cooperate in a ‘war on terror’ or in ‘migration control’ – … [which] tend not only to bypass the underlying problems but to exacerbate them” (emphasis in original). Additionally, Keen alleges that the expenses of “security systems” suck “the lifeblood from systems of public health and social security, which in turn feeds back into vulnerability to disaster”.

there is an increasing drive for security […which] tends not only to bypass the underlying problems but to exacerbate them

As Keen sees it, disasters either “hold the potential to awaken us to important underlying problems”, or “keep us in a state of distraction and morbid entertainment”, finding it important to consider their causes rather than their consequences.

Keen draws upon a wide selection of literature, covering authors including Naomi Klein, Mark Duffield, Giorgio Agamben, Ruben Andersson, Amartya Sen and Jean Drèze, as well as Michel Foucault, Susanne Jaspers, Arlie Russell Hochschild, Richard Hofstadter, and Nafeez Ahmed, among others. He pays particular attention to the work of Hannah Arendt. Her 1951 work, The Origins of Totalitarianism is a powerful and permanently valuable account of the way in which politics is framed “as a choice between a ‘lesser evil’ and some allegedly more disastrous alternative”.

[Arendt’s] 1951 work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, is a powerful and permanently valuable account of the way in which politics is framed ‘as a choice between a ‘lesser evil’ and some allegedly more disastrous alternative’.

Keen competently summarises her exposition of “action as propaganda,” upon which reality is prepared to conform to “delusions”. From his point of view, “action as propaganda” is represented by five distinct methods namely, “reproducing the enemy” (war on terror), “creating inhuman conditions” (police attacks in Calais), “blaming the victim” (austerity programmes in Greece), “undermining the idea of human rights” (the growing emphasis on removing citizenship in the UK), and “using success to ‘demonstrate’ righteousness” (Trump’s self-proclaimed powers of prediction).

Keen’s discussion of these strategies to exert control resonates with contemporary politics in the UK. One is reminded of the retrogressive character of Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s article for the Times on 8 November 2023, in the context of the Israel-Hamas war and the Armistice Day, suggesting that pro-Palestine protesters are “hate marchers”, and that the police operate with a “double standard” in the way they handle pro-Palestinian marches. This is, of course, one example of the insidious process of “painting dissent as extremism”.

Nevertheless, Keen’s use of “magical thinking”, or “the belief that particular events are causally connected, despite the absence of any plausible link between them”, is one aspect of his argument that struggles to convince. Keen is persuaded that “magical thinking” links up with a well-developed science of psychoanalysis in accordance with Sigmund Freud’s conception of the magical and how people affected by neurosis may turn away from the world of reality. But the impression given by Keen’s economic or anthropological perspective is that he may have overlooked the complexity of psychoanalysis.

Keen is persuaded that “magical thinking” links up with a well-developed science of psychoanalysis in accordance with Sigmund Freud’s conception of the magical and how people affected by neurosis may turn away from the world of reality

Here, we come to two of the chief problems of what “magical thinking” really means. First, according to Karl S. Rosengren and Jason A. French, magical thinking is “a pejorative label for thinking that differs either from that of educated adults in technologically advanced societies or the majority of society in general”. Second, they found, “it ignores the fact that thinking that appears irrational or illogical to an educated adult may be the result of lack of knowledge or experience in a particular domain or different types of knowledge or experience”. It is necessary, therefore, to understand the writings of Freud as the product of their locus nascendi. That is to say, it is dangerous to politicise the processes of psychology, or, to be more exact, to apply them outside the formalities of therapy.

To conclude, When Disasters Come Home is a book to which all those interested in current affairs, geopolitics and development studies must come sooner or later, abounding in illuminating extrapolations on the ruling and official class’s exploitation (or even manufacture) of disasters.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Kenneth Summers on Shutterstock.

China and Latin America: Development, Agency and Geopolitics – review

In China and Latin America: Development, Agency and Geopolitics, Chris Alden and Álvaro Méndez examine Latin America and the Caribbean region’s interactions with China, revealing how a complex, evolving set of bilateral economic and political relations with Beijing – from Buenos Aires to Mexico City – have shaped recent development. Mark S. Langevin contends that the book is a noteworthy contribution to an understanding of China’s footprint in the region but does not offer a robust framework for comparative analysis.

China and Latin America: Development, Agency and Geopolitics. Chris Alden and Álvaro Méndez. Bloomsbury. 2022.

China and Latin America offers a thoroughly researched account of China’s economic and political impacts in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Alden and Méndez pivot on China’s centuries-long presence in LAC to weave an analysis of trade, investment and migration patterns, detailing a thick description of economic and political relations with the region’s governments and stakeholders. Their historical examination and assessments of national government responses to China are appropriately framed by the unfolding geopolitical rivalry between Beijing and Washington. The book details China’s underlying logic and overwhelming importance to LAC, providing a valuable contribution to the growing literature assessing Beijing’s role in the region’s economic development and international relations.

China and Latin America offers a thoroughly researched account of China’s economic and political impacts in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Alden and Méndez pivot on China’s centuries-long presence in LAC to weave an analysis of trade, investment and migration patterns, detailing a thick description of economic and political relations with the region’s governments and stakeholders. Their historical examination and assessments of national government responses to China are appropriately framed by the unfolding geopolitical rivalry between Beijing and Washington. The book details China’s underlying logic and overwhelming importance to LAC, providing a valuable contribution to the growing literature assessing Beijing’s role in the region’s economic development and international relations.

China is not new to LAC; its longstanding ties with the region provide an economic and social foundation for the massive trade and investment flows in recent decades.

In the introduction, Alden and Méndez remind readers that China is not new to LAC; its longstanding ties with the region provide an economic and social foundation for the massive trade and investment flows in recent decades. In chapter one, the authors tell an intriguing story of China’s dependence on “New World silver,” European and LAC elite thirst for Chinese-produced silks and ceramics during the fall of the Ming Dynasty in the seventeenth century, and the enduring impacts of the flow of indentured Chinese workers to the region in the eighteenth century. Accordingly, Chinese working-class immigrants settled in “cities like Lima, Tijuana, Panama City and Havana…” providing a human bridge to China while suffering through waves of xenophobia and anti-Chinese repression. China and Latin America documents the economic and social linkages tempered through centuries-long trade, investment and migration – a neglected foundation for understanding LAC’s economic development in recent decades.

The book raises several leading questions. In the introduction, Alden and Méndez explore the “interests, strategies and practices of China,” questioning whether Beijing’s approach to LAC is similar to its role in Africa (14). They ask what motivates Beijing’s interests in the region and how LAC governments, firms and social actors have responded to China’s “deepening economic and political involvement in the region” (15).

Although the book is thick on economic and historical detail, its thematic analytical framework does not guide comparative explanation within LAC and across developing regions, including Africa.

Although the book is thick on economic and historical detail, its thematic analytical framework does not guide comparative explanation within LAC and across developing regions, including Africa. Alden and Méndez offer three “broad themes” for narrating their analysis: development, agency and geopolitics. These dimensions can guide examination of Beijing’s underlying logic and regional economic and political relations but are insufficient to explain the variable regional results that could stem from Chinese policies, trade and investment or even geopolitical endeavours. Consequently, Alden and Méndez emphasise “diplomacy and statecraft” and “sub-state and societal actors” as conceptual references but without the formal specification for selecting cases, testing explanations and comparing outcomes at the national and regional levels.

For example, the book explores several groups of Latin American nations and case studies of Brazil and Mexico. Chapter three’s treatment of Chile, Peru and Argentina, chapter four’s analysis of Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia, and chapter seven’s assessment of Central America and the Caribbean reflect similar patterns of development and diplomacy. However, these chapters do not present a systematic comparative analysis between these cases. Moreover, the authors’ slim selection method excludes Paraguay and Uruguay without assessing these nations’ participation in the Common Market of South America (Mercosur) along with Argentina and Brazil. Indeed, Uruguay’s recent proposal to ditch Mercosur and negotiate a bilateral trade treaty with Beijing makes it an interesting case for comparison with Mexico, given its longstanding ties to Canada and the US through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its successor pact (USMCA).

In chapter four, Alden and Méndez explain how the “sustained rise in commodity prices” – much of it fuelled by Chinese demand – “enabled these governments to seek rents from export tax revenues and direct them toward development and social programmes,” an approach the authors associate with “neo-extractivism.” Accordingly, the so-called Bolivarian republics of Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia sought to replace their dependency on the U.S. with China. Beijing embraced the opportunity, but the growing Chinese footprint “obscured the commercial intent and practices pursued by Chinese firms” (103). In response, these nations’ governments grappled with increasing Chinese debt, among other externalities brought by Chinese firms, including the “willful neglect of the concerns of local communities, environmentalists and labour activists.” Indeed, as the authors point out, even Beijing grew weary of the region’s “high expectations” and the growing “costs of entanglements” (104).

The book’s treatment of Venezuela is pivotal because it details the most extreme case of commodity export dependence and debt-trap diplomacy in the region.

The book’s treatment of Venezuela is pivotal because it details the most extreme case of commodity export dependence and debt-trap diplomacy in the region. This sets an analytical benchmark that sharply contrasts with Brazil’s diversified commodity exports to China and the parallel influx of Chinese goods, foreign direct investment and migrants, along with the incipient pattern of technology transfer through the localisation of Chinese manufacturing firms in Brazil.

On the energy front, Venezuela shifted to government control over petroleum production after Hugo Chavez’s rise to power in the late 1990s, while Brazil partially liberalised the sector during the same period. The authors assess China’s rise and growing demand for petroleum products but do not explain the divergent policy approaches taken by Caracas and Brasilia. Did Venezuela’s deepening authoritarianism and Brazil’s vibrant democracy shape Beijing’s approach to these countries and help determine the different outcomes in the petroleum sector, or are the differences limited to these countries’ respective opportunities for crude oil production for export? Moreover, do these contrasting policy-response patterns explain diplomatic outcomes, including Caracas’ growing distance from Washington? Alden and Méndez contribute to our understanding but fall short of a comparable explanation of Venezuela and Brazil’s two very different paths.

Chapter eight offers a vital perspective of China’s presence in LAC within the emerging geopolitical landscape that pits Washington against Beijing.

In conclusion, chapter eight offers a vital perspective of China’s presence in LAC within the emerging geopolitical landscape that pits Washington against Beijing. The authors explain China’s deepening engagements, becoming an observer to the Organization of American States (OAS) in 2004 and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in 2008, and President Xi Jinping’s trip to Brasilia in 2014 to attend the first Summit of Leaders of China and LAC. Xi’s confident embrace of the region did not initially spark concern in Washington, according to Alden and Méndez. However, as the authors recount, by 2018, the US National Defense Strategy Summary confirmed Washington’s acknowledgment of the strategic competition with Beijing throughout LAC.

Alden and Méndez raise a central question that should frame research and policymaking in the coming years: at what point do the citizens and leaders of LAC search for alternatives to ‘China’s dominant position in their country’s economic and political life?’

China and Latin America concludes, “No longer passive, Chinese diplomacy now looms large in the capitals and boardrooms across the region, leaving the once-unassailable US dominance scrambling to regain its standing” (175). Hence, Alden and Méndez raise a central question that should frame research and policymaking in the coming years: at what point do the citizens and leaders of LAC search for alternatives to “China’s dominant position in their country’s economic and political life?”

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Nadezda Murmakova on Shutterstock.

Africa’s Crisis Is Also an Opportunity

“If we get our policy, politics, and institutions right, African economies and society could gain greater energy and food security, built on green competition and taking strong action on climate change.“ —Professor Chuks Okereke, Director of the Centre for Climate Change and Development at Alex Ekwueme Federal University

Professor Chuks Okereke, Director of the Centre for Climate Change and Development at Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ebony State, Nigeria, argues that crisis offers African leaders a moment for deep thinking, which could lead to transformational change. But old politics, and short-term problem-solving are getting in the way of achieving such changes.

Professor Chukwumerije Okereke is Director of the Centre for Climate Change and Development at Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ebony State, Nigeria. He is a Professor of Global Governance and Public Policy at University of Bristol and Visiting Professor at the London School of Economics, UK. His specialism is climate justice, corporate climate strategies and green economy transition in Africa. He was Lead Author for the IPCC AR5 and IPCC special report on 1.5; and Coordinating Lead Author (CLA) of Chapter One for the IPCC Sixth Assessment Cycle (AR6) Working Group III. Prof. Chuks Okereke is a member of the Earth System Governance Scientific Steering Committee, and co-chair with IDDRI of the UKAMA platform.

We’ve been facing a poly-crisis caused by one disruption after another – COVID, climate, conflict, debt… Can you see something positive in this, in terms of reframing the choices open to African countries, forcing them to say hey – this isn’t working, we have to do things differently? How do you see the global picture, and the choices facing African countries where you’ve been working, especially Nigeria?

It’s a great question. I have often heard people say that the worst thing you should do with a big crisis is to waste it. Crisis can offer opportunity for reflection, for deep thinking, for transformational change. But it is not a given that a crisis does in fact bring these rewards. There is an Ibo adage that goes - we generally grow up knowing that experience is a great teacher, but actually it’s what you do with such experience that matters. We have many crises happening at the same time – climate, COVID, biodiversity, the war, debt mounting. All of these present opportunities for African countries to sit back and reflect. Good reflection should highlight that it is just not sustainable to lurch from one crisis to another.

Some of the points for reflection for African leaders include: What do these crises reveal about the position of Africa in the global political economy, and the challenges facing the continent? What do they say about the institutional arrangements we should put in place to enable us to be proactive instead of just reacting once the crisis has hit? Why is it that Africans seem to be the most affected by these crises, even when they happen in far away countries? For example, the Ukraine war showed the vulnerability of African countries to imports of grain from that region. Why is it that we don’t have food sovereignty in Africa, why can’t we feed our own people despite having huge abondance of land? The COVID crisis and the associated debts had deep and wide-ranging economic consequences. Why is it that, unlike India, we cannot produce and assemble generic drugs? Given the climate crisis and energy security – why can’t we leverage our incredible resources to achieve sustainable energy security? Look at our wind, geothermal, and solar resources. What are the key impediments which need to be removed? What are the innovation systems that need to be built? What policies and fiscal reforms should we be putting in place? These are the vital questions which this crisis should surface. But I am sad that African governments are not thinking about it in this way. There may be pockets of exception here and there. But overall, we see old politics, and reactionary mind-sets focused on short-term problem-solving, not long-term thinking for transformational outcomes. I fear this poly-crisis may indeed be wasted.

In terms of industrialisation, this has been a topic on the agenda for individual countries and the African Union for decades. Yet levels of industrialisation have plateaued or possibly decreased, as bits of manufacturing have been put out of business by cheaper goods from Asian tigers. Can industrialisation offer an agenda which works for individual countries like Nigeria, given its scale? Nigeria is clearly in a very different position to, say, Togo or Chad. Should it be a national strategy or more of a continental project?

It has to be both, and actions at each level can be mutually reinforcing. You have to start with a clear analysis of your comparative advantage, the things you can do by yourself and where your strengths lie. And then identify what needs collaboration from others. The challenge is we have not learned to step back and think long-term in ways which transcend everyday political actions. I know that many African countries now have vision 2030, vision, 2040 and vision 2050 documents, but there is often a huge disconnect between the vision statements, and everyday politics. Everyday political actions are driven by short-term interests, electoral and political gains, they are not welded to any long-term strategic vision. Another big gap is that many African countries do not have a clear framework for monitoring, evaluating and measuring themselves against the vision they set out for themselves.

There is a lot which international collaboration can provide for Africans in their quest for green industrialization but the fundamental impetus has to come from the national interest. I teach International Relations at the University and I tell my students that while COP28 can achieve a certain amount, it has essentially a catalytic role. There can be great texts and agreements that send policy signals. But, in the end, they will amount to little unless individual nations push ahead domestically. So also with industrialisation, the push has to come from individual countries. Take for example my country Nigeria. There is a need for the government to be thinking long term, such as what will be the consequence of a big drop in demand for Nigeria’s oil and our export revenue? What will be the consequence of 30-50% crop yield losses, as predicted by some models from climate change impacts? What are the 3-4 areas in which Nigeria can build its expertise and a strong presence in the green economy by 2030, 2035? There is a tendency for us to be a consumption country. We don’t think much about production. We have a total population of about 200mn people and yet we import almost everything, from toothpicks and toothpaste to high quality technological materials. This is one of the reasons we are very vulnerable to the poly-crisis; since we rely on imports for so much of what we consume. Any significant disruption in the international trade system can bring things to a halt.

Nigeria has the potential, an obligation really, to bring together the economies of West Africa, and Africa as a whole, to see how we can unlock the great green industrial potential of the continent. Some of the conversations around this would best benefit Africa if held as a group. I don’t imagine DRC or Namibia can individually get much from China, or the EU, whether on mining of critical minerals or hydrogen. But if Africa negotiates as a bloc, as a one group, they stand a much better chance of capturing more value.

We should be thinking about setting up certain industrial plants which Africa could invest in collectively, such as basic refining facilities for certain minerals. Let’s take a cluster of countries, and site the refining in particular locations, not necessarily in the place where the minerals come from. This would certainly be better than having the refining done in China, Japan or Europe. There are a number of sectors where this could work, with several regional blocs working together. Nigeria should think hard about the green economy, green industrialisation, and how to mobilise other countries to negotiate as a group. One of our challenges in Africa is that it’s often easier to fly via Paris or London than take a direct flight to your next-door neighbour. If we want trade integration, we need better connections to create the bigger market we need across the continent. Nigeria can play an important role in championing this.

What got you started with green economy, green transition?

I have been in this field for a very long time, for longer than I can remember. My PhD was on climate justice and international climate cooperation. The motivation was simple. I saw that this big crisis was also a big opportunity. I saw that if African countries do not take action, if we don’t prioritise climate justice, then climate change will aggravate poverty and inequality within Africa and globally. I could also see that there was an opportunity here to address poverty and inequality through a more collaborative way of addressing climate change. There are negative and positive dimensions to the green economy and climate. If we don’t go the green route, Africa will be losing value and bearing the brunt. But if we get it right – the policy, the politics, our institutions – it’s entirely plausible to see African economies and society gaining greater energy and food security, built on green competition and taking strong action on climate change.

If you look at the EU’s Green Deal and measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), do they represent a hurdle for Africa? Or can they help speed up the green transition?

The international regime can offer catalytic opportunities for collaboration, but countries and regions have to seize these and implement the actions needed. At one level, I am sympathetic to the EU and its Green Deal. It is ambitious. But it inevitably thinks from the EU point of view, which is completely understandable. Sometimes I wish they respected, listened and thought about the consequences of their policies and initiatives for other parts of the world, particularly Africa. They need more attention to our geographical proximity, so they can carry African governments a bit more along. It would have been good to have some sessions together to explore the likely impacts of the Green Deal, and how to achieve its objectives without imposing more constraints on Africa’s development. I get the sense that international economic justice is not uppermost in the minds of the Europeans when they are thinking through policies like the Green Deal. It has been shown that with CBAM Africa will lose a lot of export revenue, as shown by a new report from the Africa Climate Foundation and LSE which paints a bleak picture of impacts on Africa from this unilateral trade measure. This really should not be the way to go, if Africa is already bearing the brunt of climate change having contributed the least.

Equally, look at the EU’s deforestation policy, which has many good intentions for forest certification, and is intended to help ensure that EU consumption does not contribute to deforestation in Africa. But people in Ghana, especially smallholder farmers, are crying that now they face an extra level of reporting and verification. I read an analysis somewhere that in the 1970s, the average smallholder farmer in Ghana got 50-60% of the value of chocolate prices for their cocoa. Now, fifty years later, its only 10-20%. It’s a huge loss of revenue to these farmers and now we are imposing yet more unilateral measures designed to do the right thing for Europe, but which have major consequences for African farmers. African governments are keen to increase exports of timber, cocoa and other forest-based produce, to pay down their rising debts, but must now deal with these new trade measures imposed on them. The same may be said of CBAM and other elements of the EU Green Deal. I don’t begrudge the EU’s desire to speed ahead, but they must recognise and think about the negative consequences of their green policies for African producers and economies.

One big hope from green industrialisation and green transition has been pinned to green hydrogen. There have been a number of MoUs signed between different EU countries and Namibia, Mauritania and others. What have you seen that gives you confidence of the role green hydrogen could play as the great energy source of the future?

Nothing which inspires confidence, to be honest. What I have seen rather raises a lot of questions. One positive aspect is the way some African countries – such as Egypt and Namibia – have come together to collaborate, which shows some level of proactivity, and a willingness to exchange ideas and best practices. Africa is often rightly criticised for not being proactive, so we can celebrate the role Namibia is playing regarding green hydrogen. But that is where it stops. When it comes to the deals emerging from these discussions, we still see the foreign partners - the EU - dictating the terms of the contracts for green hydrogen. Just look at the choice of locations, which lie along the corridors of trade routes, which will just perpetuate export-oriented practices, as we have seen with mining. Some of this green hydrogen development is happening in defiance of national voices, who question who benefits from these deals. We do not see any emphasis on domestic energy challenges within African countries, it’s all about prospecting for cheap resources from Africa to solve Europe’s energy needs. If you want to add more value to green hydrogen, there are things which need to happen, such as building institutions, and the right fiscal policy. This big jump into hydrogen looks like an easy way out, but it won’t solve Africa’s fundamental challenges.

As you can tell, I am not as enthusiastic as many others about green hydrogen, less for technical reasons and more because the socio-economic and governance terms don’t seem right. There are some green hydrogen proposals which look very flimsy, so we need to ensure better balance in the contracts, so a greater percentage of this resource is kept within Africa to resolve the continent’s energy needs.

Might it work for green hydrogen to be used as a low carbon fuel to help establish steel, cement, fertiliser – all these highly energy intensive industrial outputs?

Yes - that’s the kind of associated development which I have in mind. We need green hydrogen as a means to achieve bigger ends, rather than it just being another commodity, something you put in the cargo-hold for selling overseas. This is the conversation which should be had. I am similarly keen on having a conversation about Africa’s gas. The energy transition in Africa needs to be phased, in a series of stages, with gas continuing to play a role for some time. Having said that, Africans need to be able to show that we won’t be wedded to fossil fuels forever, it’s a transitional stage. Governments should say - I want to use my gas in the near future to catalyse a range of industrial transformations, and then see it taper-off. These are the conversations we should be having, but we don’t hear these debates much at all. Instead, the conversations are very simple, offering binary choices – gas, or no gas. We need to think about gas in a more sophisticated way.

What about the case of Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan? They have set a goal of carbon neutrality by 2060. How do you see this – is it feasible? Are they dealing with a phased approach to gas?

I am afraid, to a large extent, Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan is just a document, with very little engagement from government. I am tempted to think that when some African countries write these plans, it is not because they feel a real need, but because they see it is demanded by the international community and as a reporting requirement. As a consequence, these reports don’t get picked up by the government, and they don’t drive the country’s economic planning and strategy. Take Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan, which is committed to net zero by 2060, and compare it with the fuel subsidy removal which some saw as a really bold policy initiative. There has been little or no link between removal of fossil fuel subsidies and the energy transition plan. No-one has said the reason why we have removed these subsidies is so that we can generate the revenue which will allow us to invest in tripling of renewable energy, from solar panels. And we cannot carry on paying this money for subsidies every month, with some lining their pockets. We have to remove the subsidies, and then find a way of helping the most vulnerable. The fossil fuel subsidy removal has been seen entirely as a fiscal challenge, not born out of a desire to move from a high to low fossil fuel economy, nor has the government seen this as a good way to get income to fuel the green economy.

The main strategy of the Nigerian government is seen in the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), which plans to increase fossil fuel production from 2mn to 3mn barrels a day. But we also have the government’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), the Long-Term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LTS) and the Energy Transition Plan (ETP). You don’t have to be a genius to recognise there is no coherence between these plans. People in the environment ministry are touting their ETP, while those in the economics ministry are using their PIA. You and I know which will win and which will lose when push comes to shove. The push behind design of the ETP was largely external. But once it had secured the commitment of a few highly influential people like then Vice-President Osinbajo, someone should have come in to say: “OK, great. What do you need to get you on track?” This announcement should have been used to turbocharge the transition. Instead, the international community felt the ETP report was just a means for Nigeria to justify continued burning of gas – they saw it just as a game to get more money. Implementation has failed woefully and caused a lot of bad blood and angst. And this was made worse because, just after the ETP launch, when the Ukraine-Russia war started, the Europeans who had been saying “no, we won’t give you any investment for gas” were the same people who were now coming to Nigeria looking for more gas. This behaviour created a sense of distrust. Then President Buhari chose not to go to COP27 at Sharm el-Sheikh, but instead wrote a strong OpEd accusing Europe of hypocrisy.

I wouldn’t say Nigeria was doing nothing to implement the ETP. When it serves them, they can refer to it, but it’s not the fundamental driver for economic strategy. For government, the things that count are liberalising trade, getting more oil, getting more gas, and fiscal reforms. We have been trying to show them that, even if your main interests are economic growth, you can still do this in a way which is sensitive to climate imperatives. There is always some room to influence what they say because they have to turn up to the G20, to climate week, to COP, etcetera so you can help with the speeches and insert a few clauses. Once they have said it, they may think a bit harder about how to make it happen.

Given the falling price of solar panels, and volatile prices for oil, are ordinary people seeing the benefits of moving from diesel generators to solar? Is this shift visible in Nigeria today?

People are certainly thinking about alternative energy supplies, not from a low carbon perspective but from the everyday imperative of diesel costing more than 900 Naira/litre, which makes people think hard about other ways of getting energy. That’s why it was such a missed opportunity to link the announcement of cuts to the fossil fuel subsidy with, for example, a cut in duty on solar panels. The government could have said – “Look! There’s an opportunity here.” We should have seen money going into power research in this area, a proper plan to manufacture solar panels, and provide lots of other incentives. That’s what you call “joined-up policy”. I think a lot more people would be willing to switch to solar panels now following the removal of subsidies.

The Unequal Effects of Globalization – review

In The Unequal Effects of Globalization, Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg looks at globalisation’s effect on inequality, emphasising regional frictions, rising corporate profits and multilateralism as focal points and arguing for new, “place-based” policies in response. Though Goldberg provides a sharp analysis of global trade, Ivan Radanović questions whether her proposals can effectively tackle critical issues from poverty to climate change.

The Unequal Effects of Globalization. Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg (with Greg Larson). MIT Press. 2023.

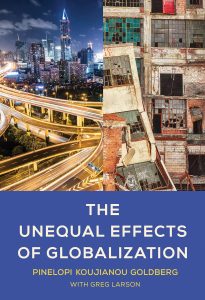

Glancing at the megalopolis on the left and abandoned building on the right side оf the book cover, I made an assumption about its narration: from the 1980s onwards, trade unions and states were blamed for rising inflation and unemployment. Fiscal cuts, deregulation and privatisation replaced public interest with private ones: maximising profit, firms outsourcing manufacture. What at first went alongside and later instead of promised economic efficiency was wealth accumulation at the top and the surge of corporate profits. As workers’ real wages fell behind, inequality grew.

Glancing at the megalopolis on the left and abandoned building on the right side оf the book cover, I made an assumption about its narration: from the 1980s onwards, trade unions and states were blamed for rising inflation and unemployment. Fiscal cuts, deregulation and privatisation replaced public interest with private ones: maximising profit, firms outsourcing manufacture. What at first went alongside and later instead of promised economic efficiency was wealth accumulation at the top and the surge of corporate profits. As workers’ real wages fell behind, inequality grew.

As an academic specialising in applied microeconomics, Goldberg investigates globalisation’s many dimensions and complex interactions, from early trade globalisation to the rise of China, from western deindustrialisation to its effects on global poverty, inequality, labour markets and firm dynamics.

I was wrong. As an academic specialising in applied microeconomics, Goldberg investigates globalisation’s many dimensions and complex interactions, from early trade globalisation to the rise of China, from western deindustrialisation to its effects on global poverty, inequality, labour markets and firm dynamics. The book does concur with my assumption, but it engages with it in a more unique way.

According to Goldberg, the increase in global trade is due to developing countries’ entry into international trade since the 1990s.

Starting from an economic definition of globalisation, the author emphasises the lowest ever levels of (measurable) trade barriers and, consequently, the highest global trade volumes. According to Goldberg, the increase in global trade is due to developing countries’ entry into international trade since the 1990s. It is inseparable from global value chains (GVCs), complex production processes that – from raw material to product design – take place in different countries. The author argues that “the increasing importance of developing countries in world trade reflects their participation in GVCs” (6). That is the creation story of hyperglobalisation. For Goldberg, it is observable by the total export share in global GDP: “being fairly constant in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it began rising after World War II and accelerated dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s.” That is exactly when the World Trade Organization (WTO) was founded, and many multilateral trade agreements were signed. The key was trade policy.

But not everyone agreed. Some economists, including Land Pritchett and Andrew Rose, contended the growth was not due to trade, but the development of technology and fall of transportation costs. Goldberg rejects this argument, pointing out that technology was developing long before. Hyperglobalisation started because trade policies encouraged multilateralism; “Trade policy – especially the creation of a predictably stable global trading environment – was at least as important as technological development“ (17).

Since international trade is largely about distributional gains and losses, the key question is whether the recent tensions and protectionism – such as Brexit, Trumpism and American trade war with China, to name the most visible examples – are just blips in irreversible globalisation, or signs of deglobalisation.

This is important because international trade is a perennial source of discontent within globalisation, and exploring its causes is the primary focus of this book. Since international trade is largely about distributional gains and losses, the key question is whether the recent tensions and protectionism – such as Brexit, Trumpism and American trade war with China, to name the most visible examples – are just blips in irreversible globalisation, or signs of deglobalisation. It depends on policy choices.

In the second half of the book, Goldberg turns to inequality and differentiates it into global inequality and intra-country inequality. From the global perspective, the author points out two major contributions. The famous “elephant curve“ developed by Lakner and Milanovic (2016, p. 31) showed very high income growth rates for world’s poorer groups from 1980 to 2013. This primary observation is accompanied, however, by the almost stagnant income of the middle classes in developed countries (the bottom of elephant’s trunk) and high rates of growth for the world’s top one percent (its top). But how high? The answer came five years later, when Thomas Piketty and colleagues concluded (2018, p. 13) this elite group captured 27 per cent of global income growth between 1980 and 2016.

Analysing internal inequalities, Goldberg states that globalisation affects people twofold: as workers and as consumers.

This still does not refute that income rose for all groups, remarkably reducing poverty. But what about inequalities? Goldberg further investigates whether there is a trade-off between global inequality and within-country inequality. Analysing internal inequalities, Goldberg states that globalisation affects people twofold: as workers and as consumers. These effects are well-researched in developed countries like the USA, where trade liberalisation with China since the late 1990s brought multi-million job losses. Citing scholars such as David Autor, Gordon Hanson, David Dorn, and Kaveh Majlesi, Goldberg finds this trend disturbing for ordinary citizens. One could suppose that although jobs were lost, this was compensated by lower consumer prices which benefitted everyone. However, that’s exactly what did not happen in the US. Firms took almost all benefits, which meant that greater trade did not reduce consumer inequality. Crucially, even if it had, it would not compensate for the negative effects on the labour market. Therefore, as Deaton and Case argued, it is no surprise that the millions of jobless, low-educated Americans whose quality of life and even life expectancy is in decline oppose globalisation.

But the advent of trade with China cannot fully explain this issue. There are severe labour mobility frictions that prevent people from moving to another town, county or state to find a better job. That is an American trademark since, as Goldberg suggests, “Europe normalized their trade with China much earlier and in a much more gradual manner“ (55). In other words – a policy problem needs policy solution.

[Trade’s] adverse effects, such as the exceptionally high benefit claimed by the top one percent and the stagnation of the middle class in the Global North, cannot be attributed to trade per se, but to a lack of policies that absorb disruptions.