afghanistan

Corrupt Australian firm busted as intelligence front

Aussie intel cutout Omni Executive accused of leveraging ties to abusive units in Afghanistan to rake in massive contracts. The firm allegedly inked the no-bid deals while conducting warrantless domestic spying ops. A whistleblower complaint obtained by The Grayzone alleges industrial scale corruption by three former SAS operatives linked to a private firm, which operates as a “front company…for deployable, offshore covert or clandestine intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance activities” on behalf of the Australian government. The document, submitted anonymously by […]

The post Corrupt Australian firm busted as intelligence front first appeared on The Grayzone.

The post Corrupt Australian firm busted as intelligence front appeared first on The Grayzone.

The US and ISIS: It’s Complicated

While ISIS-K has claimed responsibility for the Moscow shooting, Russian President Vladimir Putin has suggested that the United States might have been behind the attack.

Although he provided no evidence for his claim, it is true that ISIS and the United States government have a long and complicated relationship, with Washington using the group for its own geopolitical purposes and that former ISIS fighters are active in Ukraine, as MintPress News explores.

A Brutal Attack

On March 22, gunmen opened fire at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow, killing at least 143 people. Authorities apprehended four suspects who they claim were fleeing towards Ukraine. The attack was only one of a number planned. After receiving international tip-offs, Russian police foiled several other operations.

ISIS-K, the Islamic State’s Afghanistan and Pakistan division, immediately took responsibility for the shooting, with Western powers – especially the United States – treating the matter as an open and shut case. Vladimir Putin, however, felt differently, implying that Ukraine or even the United States might have been somehow involved. “We know who carried out the attack. But we are interested in knowing who ordered the attack,” he said, adding: “The question immediately arises: who benefits from this?”

Moscow has long accused Ukrainian intelligence services of recruiting ISIS fighters to join forces against their common enemy. Far-right paramilitary group Right Sektor is believed to have trained and absorbed a number of ex-ISIS soldiers from the Caucuses region, and Ukrainian militias have been seen sporting ISIS patches. However, there are no clear and official links between the Ukrainian government and ISIS, and the suspects – all Tajiks – have no publicly known connections to Ukraine.

Last Year, Ukrainian militants wearing ISIS patches were pictured on camera by the press – probably unintentionally. pic.twitter.com/5SvfLD6pKJ

— MintPress News (@MintPressNews) March 26, 2024

This is not the first time that ISIS has targeted Russia. In 2015, the group took responsibility for the attack on Metrojet Flight 9268, which killed 224 people. It was also reportedly behind the January 2024 attacks on Iran that killed more than 100 people, commemorating the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian general responsible for crushing ISIS as a force in Iraq and Syria.

Giving Birth To A Monster

A host of U.S. adversaries have claimed that ISIS enjoys an extremely close working relationship with the U.S. government, sometimes acting as a virtual cat’s-paw of Washington. Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, for instance, has accused the U.S. of ferrying ISIS fighters around the Middle East, from battle zone to battle zone. Former Afghan President Hamid Karzai stated that he considers ISIS to be a “tool” of the United States, saying:

I do not differentiate at all between ISIS and America.”

And just this week, the Syrian Foreign Ministry demanded:

the U.S. should end its illegitimate presence on Syrian territory, and end its open support and fund for Daesh [ISIS] and other terrorist organizations.”

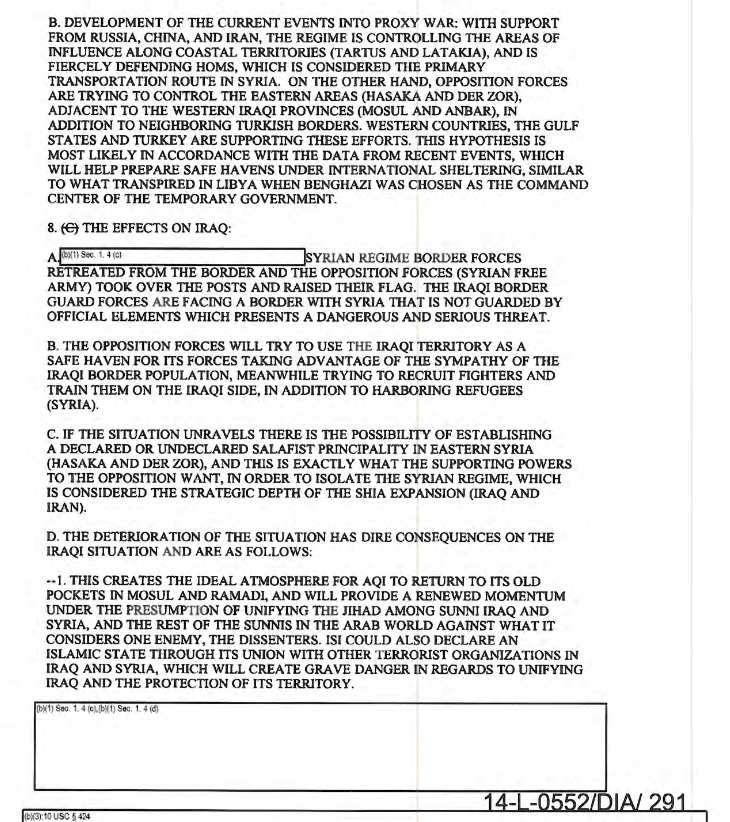

It was in Syria that the goals of ISIS and the United States most closely aligned. In 2015, Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, the former Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (D.I.A.), lamented that ISIS arose out of a “willful decision” by the U.S. government. A declassified D.I.A. report says as much, noting that the “major forces driving the insurgency in Syria” were ISIS and Al-Qaeda. “There is the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist principality in Eastern Syria,” the report noted excitedly, adding that “[T]his is exactly what the supporting powers to the opposition [i.e., the U.S. and its allies] want.”

A now-declassified DoD document shows US military officials believed backing AQ and ISIS in Syria could help defeat Assad

A now-declassified DoD document shows US military officials believed backing AQ and ISIS in Syria could help defeat Assad

Throughout the 2010s, images of ISIS’ brutality consistently went viral and led to news bulletins around the world, providing the United States with a convenient enemy to justify keeping its troops in Iraq and Syria. And yet, throughout the decade, the U.S. and its allies were also using ISIS to weaken the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. As then-Vice President Joe Biden said, Turkey, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia were:

[S]o determined to take down Assad and essentially have a proxy Sunni-Shia war, what did they do? They poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens, thousands of tonnes of weapons into anyone who would fight against Assad.”

This included ISIS, Biden said. He later apologized for his remarks after they went viral. Nevertheless, the U.S. also supported a wide range of radical groups against Assad. Operation Timber Sycamore was the most extensive and most expensive C.I.A. project in the agency’s history. Costing more than $1 billion, the agency attempted to raise, train, equip and pay for a standing army of rebels to overthrow the government.

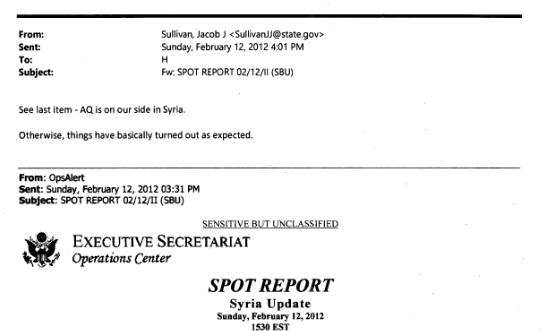

It is now widely acknowledged that large numbers of those trained by the C.I.A. were radical extremists. As National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan told Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in an email published by WikiLeaks:

AQ [Al-Qaeda] is on our side in Syria.”

Clinton herself was well aware of the situation in Syria, noting that Qatar and Saudi Arabia were:

providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIL [ISIS] and other radical Sunni groups in the region.”

While ISIS regularly attacked a wide range of enemies in the Middle East, it actually apologized to Israel in 2017 after its fighters mistakenly launched a mortar attack on the IDF in the occupied Golan Heights region of Syria.

That same year, the United States launched a significant attack on ISIS-K in Afghanistan, dropping the GBU-43/B MOAB bomb on a network of tunnels in Nangarhar Province. The bomb was the largest non-nuclear strike ever recorded and reportedly killed at least 96 ISIS operatives. Yet ISIS did not appear particularly interested in striking back at the U.S. Instead, it waited until the American departure from Afghanistan to launch a series of devastating attacks on the new Taliban government. This included a bombing at Kabul International Airport, killing more than 180 people, and the Kunduz Mosque Bombing two months later. The Taliban accused ISIS of carrying out a U.S.-ordered campaign of destabilization.

Global Terror Network

While the precise relationship between ISIS and the United States will surely never be known, what is clear is that, for decades, Washington has armed and trained terrorist groups around the world. In Libya, the U.S. joined forces with jihadist militias to topple the secular leader Muammar Gaddafi. Not only was Libya transformed from North Africa’s most prosperous country into a political and economic basket case, but the fighting unleashed a wave of destabilization across the entire region – something which continues to this day.

In Nicaragua, the U.S. sponsored far-right death squads in an attempt to overthrow the leftist Sandinistas. Those forces killed and tortured vast numbers of men, women and children; U.S.-trained groups are thought to have killed around 2% of the Nicaraguan population. The Reagan administration justified their intervention in Nicaragua by stating that the country represented a “mounting danger in Central America that threatens the security of the United States.” Oxfam retorted that the real “threat” Nicaragua posed was that it was a “good example” for other nations to follow.

Meanwhile, in Colombia, successive administrations helped to arm and train conservative paramilitary forces that prosecuted a brutal war against not only leftist guerilla forces but the civilian population as a whole. The extraordinary violence led to the internal displacement of more than 7.4 million Colombians.

Donald Trump once quipped that Barack Obama was “the founder of ISIS.” While this is not true, there is no doubt that the United States did indeed nurture the group, watching it expand into the force it is today. It has, at the very least, turned a blind eye to its operations and abetted it in its attack against their common enemies. In this sense, at least, with every ISIS attack, there is some blood on Washington’s hands.

Feature photo | A US-backed anti-government fighter mans a heavy machine gun next to a US soldier in al Tanf. Hammurabi’s Justice News | AP | Modification: MintPress News

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.

The post The US and ISIS: It’s Complicated appeared first on MintPress News.

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace – review

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox brings together scholars to analyse the failure of Afghan state-building, the Taliban’s resurgence and the country’s future. Anil Kaan Yildirim finds the book a valuable resource for understanding challenges the country faces, including women’s rights, the drugs economies and human trafficking and exploitation. However, he objects to the inclusion of a chapter which makes a geographically deterministic appraisal of Afghanistan’s governance.

Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace. Michael Cox (ed.). LSE Press. 2022.

This book is available Open Access here.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

In Afghanistan: Long War, Forgotten Peace, Michael Cox gathers scholars, policymakers, and public intellectuals to shed light on the factors contributing to the failure of Afghan state-building, the successful takeover by the Taliban, and to share some insights on the country’s future. The chapters in the collection impart valuable insights on international law, human trafficking, women’s rights, NATO, and the international drug trade, with the exception of one essay that uses a problematic framework in its analysis of Afghan statehood and seems out of place within the book.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country.

One of the main tasks of any state-building process is to create a political sphere that includes all parties to decide on policies and strategies shaping the future of the country. However, in the case of Afghanistan, as argued by Michael Callen and Shahim Kabuli in Chapter Three, the de facto power structure did not align with the de jure systems of institutions. Excluding the Taliban from political discussions, adopting a fundamentally flawed and exclusionary electoral system, and employing a centralised presidential system which did not correspond to Afghan “diversity and reality” have been the “three sins” of the Afghanistan project. Along with these mistakes, the authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China that tried to attract the power-holders of the country. This powerful essay points out the three sins in the creation of the structure and other dynamics that destabilised the country. Thus, the state-building project collapsed not because Afghanistan was unsuited to democracy, but because of a combination of many different mistakes.

The authors also identify the issues that created a “dysfunctional” state-building, including the lack of complete Afghan sovereignty within regional power dynamics, the diversion of the US’s focus to Iraq, and other foreign influences such as Russia and China

The role of women in the Afghan state-building effort is highly contested among different power holders, the international community, and the Taliban. Writing in this context in Chapter Six, Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists. The highly masculinised country following many years of different wars created a challenging political and social area for women. Therefore, all changes in the political sphere resulted in a change in the lives of women.

Nargis Nehan explores the issue of women’s rights in Afghanistan before and after 9/11, positioning the matter within the spectrum of extremists, fundamentalists, and modernists.

As an internationalised state-building project, Afghanistan has challenged international institutions and norms. Devika Hovell and Michelle Hughes examine the US and its allies’ interpretation and application of international law in military intervention in Afghanistan. With discussion of several steps and actors of the intervention, they demonstrate how this operation stretched the definitions of self-defence, credibility, legal justification, and authority within international realm.

The book explores several other key problems in the country. These include Thi Hoang’s chapter on human trafficking problems such as forced labour, organ trafficking and sexual exploitation; John Collins, Shehryar Fazli and Ian Tennant’s chapter on the past and future of the international drug trade in Afghanistan; Leslie Vinjamuri on the future of the US’s global politics after its withdrawal from the state; and Feng Zhang on the Chinese government’s policy on Afghanistan.

The essays mentioned above demonstrate what happened, what could have been evaded and what the future holds for Afghanistan. However, the essay, “Afghanistan: Learning from History?” by Rodric Braithwaite is a questionable inclusion in the volume. By emphasising geographical determinism, this piece a problematic perspective on Afghanistan. The essay argues that the failure of the West’s state-building project was down to the “wild” character of Afghan governance historically, which he deems “… a combination of bribery, ruthlessness towards the weak, compromise with the powerful, keeping the key factions in balance and leaving well alone … (17)” or “… nepotism, compromise, bribery, and occasional threat” (26-27). This perspective paints a false image of how Afghan history is characterised by unethical, even brutal methods of governance. Also in this essay are many problematic cultural claims such as “… Afghans are good at dying for their country … (18).”

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative

The limitation of the entire Afghan agency, history and political culture to a ruthless character and geography that always produces “terrible results” for state-building is a false narrative, which is reflected in and supported by the postcolonial term for Afghanistan: the “graveyard of empires”. While many different tribes, states, and empires have successfully existed in the country, Western colonial armies’ defeats and recent state-building failures should not misrepresent the country as a savage place in need of taming. Rather, as the other essays in the book argue, research on these failures should examine the West’s role in precipitating them.

Not only does this piece disrespect the scholarship (including other authors of the book) by asserting the ontological ungovernability of the country, but its deterministic stance also disregards the thousands of lives lost in the struggle to contribute to Afghan life those who believed that the future is not destined by the past but can be built today. Additionally, using only three references (with one being the author’s own book), referring to the US as “America”, random usage of different terms and not providing the source of a quotation are all quite problematic for a lessons-learned-from-history essay.

Beyond the limitations of the essay in terms of how it frames the past, what is more damaging is the creation of a false image of Afghanistan for future researchers and policymakers. For the points mentioned above, including the false narrative of ‘graveyard of empires’, Nivi Manchanda’s Imagining Afghanistan: The History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (2020) is worth consulting for in-depth insight into the colonial knowledge production system and its problematic portrayal of Afghanistan.

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation

Braithwaite’s essay excepted, this book, exploring different political and historical issues from various perspectives, provides significant insights into what happened in Afghanistan and what the future holds for the nation. For practitioners, policymakers, and scholars seeking a broad perspective on state-building problems, policy limitations and relevant research areas in Afghanistan, this collection is a useful resource.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Trent Inness on Shutterstock.