Wednesday, 2 March 2016 - 8:33pm

I'm assuming the new sign says "Pioneer Park" because there wasn't room for one that says "Pioneer Roadside Verge". I can't say I know what steel history pods are, but I'm glad they're "vandal proof". The last thing you want when you've taken the trouble — through the sheer goodness of your heart, not because there's any demonstrable need for it — to plough a bloody great road through a very small park, is for vandals to come in and wreck it all.

I fondly remember shopping at Gowings when I used to live in Sydney, so I'm very pleased that Gowings Bros. Investments has chipped in to partially fund this expensive elective park-ectomy operation. It appears the brothers Gowing consider the welfare of the Coffs Harbour community a vital part of their business. And they would never let a vital part of their business go bust, would they?

What? Have I missed something?

Excellent he-said-she-said reporting, by the way. A master class in the art of non-investigative journalism. It's like I was there in the room, yet curiously unable to ask a question, or subsequently fact-check or seek expert opinion. I take my hat off to you! Or at least I say I do. You don't need to confirm this.

Sunday, 28 February 2016 - 8:35am

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Helicopters already exist. If you know where to look — Neil Wilson braves the slippery slope from advocating for central bank independence to…:

And then you move onto the question of war. If parliament can't be trusted with money, or social security, why should it be trusted in sending people to their deaths. […] Of course if the generals are in charge and are able to deploy troops independently of parliament, then we would rightly call that a military dictatorship. Therefore the notion of an independent central bank should be called out for what it is - an economic dictatorship ruled over by a class of individuals who look after the interests of the bankers and creditors and want to prevent government having first access to the resources of the country. Those supporting the idea are excuse makers for that destructive regime.

- The difficulty of ‘neoliberalism’ — Will Davies, Political Economy Research Centre:

The reason ‘neoliberalism’ appears to defy easy definition (especially to those with an orthodox training in economics or policy science) is that it refers to a necessarily interdisciplinary, colonising process. It is not about the use of markets or competition to solve narrowly economic problems, but about extending them to address fundamental problems of modernity – a sociological concept if ever there was one. For the same reasons, it remains endlessly incomplete, pushing the boundaries of economic rationality into more and more new territories. […] The dramatic rise of student indebtedness in the UK makes little economic sense for anyone (even the government) but it succeeds in placing higher education in a quantitative framework, linking past, present and future.

- Keywords for the Age of Austerity 24: Sullen — John Patrick Leary:

The problem is not just that education is vocational here, because there’s nothing wrong with vocational education per se, nor is “critical thinking” or moral education or whatever you want to call it necessarily un-vocational anyway. Rather, it is the way “academic entrepreneurship” encourages students and others to see education, a public service subsidized to great extent by the people, as a publicly-funded adjunct of private business, useful for research, development, and employee training. Lesson number 1 of entrepreneurship class: Why take a financial risk when you can just outsource it to someone else?

- The Great Malaise Continues — Joseph Stiglitz:

The obstacles the global economy faces are not rooted in economics, but in politics and ideology. The private sector created the inequality and environmental degradation with which we must now reckon. Markets won’t be able to solve these and other critical problems that they have created, or restore prosperity, on their own. Active government policies are needed. That means overcoming deficit fetishism.

- New Research. Inequality of Wealth Makes Us Short and Dead — Peter Turchin in Evonomics:

So, the life expectancy of white middle-aged males has declined, and the average height of black women has also declined. Is this the beginning of a more broadly based trend, in which the biological well-being of the “other half”—the 50 percent of the poorer Americans—will decline?

- ‘Helicopter tax credits’ to accelerate economic recovery in Italy (and other Eurozone countries) — Biagio Bossone and Marco Cattaneo at VoxEU.org:

Tax Credit Certificates (TCCs) […] are assigned to households in inverse proportion to their income, both for social equity purposes and to incentivise consumption. TCC allocations to enterprises are proportional to their labour costs, and act as labour-cost cutting devices, immediately improving their competitiveness, as any internal or external devaluation would do. Greater export and import substitution following price reductions not only create more output and employment, they also offset the impact of increased demand on the external trade balance. Smaller amounts of TCCs can also be issued and used by the government to pay for public infrastructure initiatives and social welfare programs.

- The DWP is trying to psychologically 'reprogramme' the unemployed, study finds — Jon Stone, The Independent:

A study backed by the Wellcome Trust found that people without jobs were subject to humiliating “reprogramming” by authorities designed to change their mental states. The researchers said the new approach, which forced upon the unemployed a “requirement to demonstrate certain attitudes or attributes in order to receive benefits or other support, notably food” raised major ethical issues.

- Economists Don't Know Much About the Economy, #46,523: The Story of the Robots — Dean Baker in HuffPostBiz:

Patent and copyright protection are not laws of nature, they come from the government. And in recent years we have been making them stronger and longer. […] In the absence of these protections, we might all look forward to paying a few dollars for the robots that will clean our houses, cook our food, and drive us wherever we want to go. Low cost robots would make almost all of us richer. Only if the government imposes patent monopolies that keep robots expensive do we have to worry about a redistribution from the rest of us to those who "own" the technology.

- Huge currency zones don’t work – we need one per city — Mark Griffith in Aeon:

In the 1970s, the American/Canadian economist Jane Jacobs reached a radically simple insight. Her lifelong interest in urban history convinced her that cities, not countries, drive economics. Cities are messy, unplanned places where people who otherwise would never meet devise joint projects. Hence, Jacobs argued, all innovation happens in cities. It made sense, then, that each city’s currency should follow its business cycle. Forcing two or more cities to share one currency slowly pumps up one city and sickens the others.

- Designer nights out: good urban planning can reduce drunken violence — Kees Dorst in The Conversation:

It is easier said than done, but we need to think away from knee-jerk reactions - where branding an incident as “alcohol-related violence” naturally puts the focus on policies around alcohol service restriction. There is so much more that can be done to keep young people safe at night.

- Why bullshit is no laughing matter — Gordon Pennycook in Aeon:

It is now very common for proponents of alternative medicine to emphasise ‘open-mindedness’. Unfortunately, this can entail disregarding empirical evidence. For example, many anti-vaxxers do not appear to care that Andrew Wakefield’s infamous article in the Lancet in 1998 drawing a link between the MMR vaccine and autism has long been discredited and retracted. Indeed, straight-up explanations of this fact do little to dissuade those who have fallen prey to anti-vaxxer bullshit. Diseases such as measles and mumps are making a comeback in the US and, according to at least one website, there have been more than 9,000 preventable deaths due to failures to vaccinate in the US since 2007. Bullshit is indeed no laughing matter.

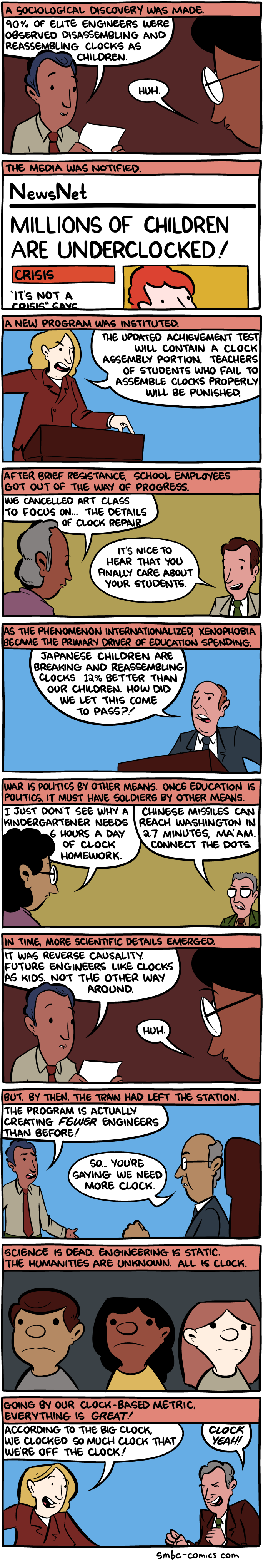

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal by Zach Weinersmith [Yes, education really works like this]:

Wednesday, 24 February 2016 - 6:57pm

At the Campaign for America's Future, Dave Johnson has a comprehensive roundup of the Sanders “Economic Plan” Controversy. The controversy is practically non-existant outside of the left wing of the Republican Party, i.e. the Clinton/Obama/Clinton Democrats. The plan is pretty much what you'd expect from a New Dealer, as Chomsky characterises Sanders. It's a welcome change from policies that have created the post-GFC malaise, but hardly radical or historically unprecedented.

As you'd expect, economists with intelligence and integrity like Bill Black and Jamie Galbraith did their best to introduce some reason to public discourse, while journalists on the economics beat largely ignored tham and scrambled to stake out a position that they could defend as balanced. As you'd also expect, but nonetheless disappointingly, Paul Krugman lined up with those he would usually deride as Very Serious People (VSPs). I generally enjoy Krugman. He's witty and articulate, and performs a useful service against Republican politicians beloved of VSPs such as Ron Paul, Paul Ryan, Rand Paul, and Ryan Rand. (Hang on; I think one of those isn't a real person. Maybe more than one.)

Sadly, Krugman is not inclined to entertain ideas outside the range of opinions between Clinton and Bush, or if you prefer, Clinton and Bush (or Bush). And those issues upon which "moderate" Republicans and Democrats agree do not for Krugman count as contestable issues; they are part of the built-in political furniture. In this sense, he's as much a VSP as anybody. If he wasn't, he wouldn't be doing his job.

The New York Times' readership is the one percent. It makes sense therefore to maintain that real economic injustice is the work of the one-tenth of one percent. "It's not you, dear reader, it's those cads who buy the TImes but don't read my column who are to blame." Magnifying marginal distinctions, dismissing the significant, and excluding the challenging comes with the territory.

As a commentator, Krugman is a Jerry Seinfeld at a time which requires a Bill Hicks. In the second term of the Sanders presidency, I will be happy to read his wry observations about airline food and the latest crazy things Senator Ivanka Trump has been saying. In the meantime…

The Ivy League and the Lantana League

[I'm archiving for posterity a few articles I wrote for a now-defunct website. This is the third, from June 2014; here is the first, and the second.]

Good afternoon everyone, and welcome to our external students who are tuning in via the Internet. To those external students I would like to ask that you put some pants on for the duration of this lecture, and to refrain from playing Angry Birds. I have no idea what it is to "play Angry Birds"; I assume it's a euphemism for something quite distasteful.

Good afternoon everyone, and welcome to our external students who are tuning in via the Internet. To those external students I would like to ask that you put some pants on for the duration of this lecture, and to refrain from playing Angry Birds. I have no idea what it is to "play Angry Birds"; I assume it's a euphemism for something quite distasteful.

This afternoon we are considering the current state of university education in Australia. I therefore recommend following this lecture with a generous measure of the intoxicating substance of your choice. First, let us consider those characteristics of any conceivable higher education system which are universally considered uncontroversial, indeed axiomatic.

The first axiom is that the primary purpose of the Australian university system is to produce a skilled workforce to meet the needs of industry. This has been the case ever since the alleged expansion of the university system with the "Dawkins revolution" of the late 1980s. As former education minister John Dawkins himself declares, failure to take the focus of higher education away from the intellectual development of students, and reposition it towards the needs of business, would have left the Thatcherite economic reforms of the Hawke/Keating era incomplete. The trade and technical colleges that subsequently merged to nominally join the university system have largely carried on in practice as vocational training institutions. Wherever they have ventured into disciplines traditionally considered academic, the "new universities" of the last quarter of a century still, indeed increasingly, stress vocational outcomes. For example, in it's 2015 prospectus, Southern Cross University (the rebranded Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education) provides, for each of their courses, a list of the professions for which that course provides "work-ready skills", with even the School of Arts and Social Sciences promising "degrees which put you in the workplace".

The second axiom is that the benefits of having a higher education system overwhelmingly accrue to the student. To reconcile this belief with the demand that universities must primarily serve the needs of business requires sturdy ideological blinkers, or at least the ability to maintain a logical contradiction whenever it is in your interest to do so.

A necessary corollary of the first two axioms is that the public purse has next to no business contributing to the funding of higher eduction, and that public funding of public higher education can only decrease over time. The consensus on this is quite striking, across all institutions and both major political parties. Indeed, out on the lunatic fringe, some vice chancellors have been pleading for less government funding in exchange for more market-based deregulation.

So if everybody, or at least anybody who matters, agrees on the fundamental characteristics of the Australian higher education system, why such fuss about the latest wave of incremental change enshrined in the latest federal budget? Well, there is one fundamental difference of opinion among university administrators and between the Coalition and the ALP; that is, whether it is worth preserving the role of traditional, pre-Dawkins univerities in any form.

The current government is keen to push our higher education system from neoliberalism to full-blown neoconservatism, with (small "l") liberal education confined to Abbott's bunyip aristocracy, professional training for the managerial class, and tough love for the proles. The Labor party differs only in that it sees no point in liberal education at all. If one wants to participate in civic discourse, and needs to learn the finer points of politicking and rhetoric, one goes about it the traditional way: get a job at the ACTU and work your way up the ranks until you reach preselection for a safe seat.

The older, more prestigious universities which make up the Group of Eight (Go8) have never been particularly happy about the Dawkins revolution and subsequent aftershocks. While the far greater number of new universities have staked their futures on a mass market in higher education, the Go8 have nothing to gain, in a commercialised system, by any implied equivalence between themselves and the former polytechnics. On the other hand the new universities have flourished under the "demand driven system", introduced in 2012, where they are free to accept as many publicly-subsidised students as they can bear, on the premise that the resulting degree is as solid a guarantee of a well-paid career as a degree from any institution in the country.

While much fun has been had from the revelation that federal treasurer Joe Hockey was, in his own student days, a protestor against student fees, the prime minister can at least boast of more ideological constistency. In contrast to the later, largely phony expansion of university student numbers resulting from the Dawkins annexation of non-university institutions, there was a real, almost tenfold, increase in student numbers between 1955 and 1975. The young Tony Abbott, as a vigorous student reactionary at Sydney University in the 1970s, found to his horror that the wrong sort of people were attending his university and actively engaging with the wrong sort of ideas.

It should therefore hardly come as a shock that the Jesuit-and-sandstone-educated Prime Minister and his Jesuit-and-sandstone-educated education minister might seek a compromise that would restore some of the pre-war elitism to the prestige end of the market, while also accommodating the wish list of the mass market providers of vocational "learning outcomes". However when even Fred Hilmer, vice chancellor of Go8 member the University of NSW, and previously a lukewarm critic of deregulation, welcomed the government's vision of a US-style "diversity" between an Australian Ivy League and what we might call a "Lantana League" of second-rate institutions, the administrators of the latter seemed oblivious to the evidence that a deal had been done to explicitly segment the higher education market into a prestige line of products, and a low-margin, no-frills brand.

The trick to being a successful free market advocate lies in knowing which markets, when deregulated, will naturally deliver your desired outcomes, and which regulations should be left well alone. The demand driven system, which uncapped the number of students a university could accept in each course, has served the vocational universities well, allowing them to drop those courses that were difficult to sell and focus on the mass marketing of degrees as future employment vouchers. Further expansion of the demand driven system to sub-bachelor two-year courses was merely expected to add proportionally more cars to the gravy train. So when the government's Commission of Audit (a.k.a. the razor gang) also recommended tuition fee deregulation, Peter Lee, Chair of the Regional Universities Network and vice chancellor of Southern Cross University, greeted the recommendation as "no surprise" and welcomed a "robust discussion". For the benefit of the millenial generation, this can be translated as: "WTF??? OMG!!!"

Fee deregulation would mean that the Ivy League would be free to charge what the market would bear, prompting speculation of five-figure annual tuition fees, while the Lantana League would be forced to admit that their credentials were worth perhaps a tenth of the Ivy's, or else simply lose customers, or perhaps both. In the face of these prospects, Professor Lee appealed to the notion of the university as a "public good", a notion conspicuously absent just weeks earlier, when yet more of the less vocational units of study were mercilessly cut from his own campuses for the second term of 2014.

I must admit to some degree of schadenfreude at the thought of my own university's vice chancellor in the character of Wile E. Coyote, strapping on his ACME-brand, market-driven roller skates, and so enthused by the initial accelleration that he's unaware that he's shot off a cliff, then blinking with confusion at his sudden loss of forward motion, looking down, and finally holding aloft a little sign saying "FOR THE LOVE OF THE PUBLIC GOOD, HELP!" before plummeting to the canyon floor and vanishing in a tiny "poof" of dust. Sadly, this is poor consolation. Regardless of the outcome of the proposed robust debate, the Lantana League already exists, independant of the prospects for an Ivy League, and is the only available option for students in much of the country outside the major capital cities. I can testify to this from first hand experience here in Coffs Harbour.

The first thing you will notice as a Lantana League undergraduate is that your study options are somewhat constrained. Each Lantana League campus will have a business school, a few other vocational disciplines, and perhaps a prestige vanity school (in the case of SCU Coffs, psychology) whose presence is tolerated as long as it is able to generate fine-sounding press releases and revenue-raising partnerships with industry. Rare exceptions notwithstanding, you will not find many of the traditional subjects of a liberal education available to study.

In fact the "study of" a subject is eschewed in favour of the "study for" a career. The Lantana League is steeped in a culture of instrumentalism. Nobody here attends university because they want to attend university; they are working/paying for the award of an employment voucher. TV advertisements for Lantana League institutions repeatedly hit the word "career" as if it were a punctuation mark, while the word "education" is never heard. The idea that there might be intrinsic value in what you study or the work you do while at university is anathema.

Lectures are discouraged in the Lantana League, in favour of the verbatim recitation of administratively-approved bullet points from Powerpoint slides. External students recieve these as an audio or video file download. Often, so do internal students; lectures nominally scheduled as on-campus are frequently teleconferenced in from another campus to save money. Even when a recitation is given in-person, that person must stand rooted to the spot behind a Star-Trek-like panel of technology (which they don't really know how to operate), because the camera trained on them is unmanned and stationary, and the majority of their audience is out in cyberspace. Engagement with the audience in the room is physically near-impossible under these conditions and, in any case, there is an unspoken pact between lecturer and students to maintain an imaginary partition between them in order to preserve equity with remote students. It would be unfair to take the opportunity to ask a question when the majority of your fellow students have no such opportunity.

These recitations are literally audiovisual crib notes. Indeed prior to an exam, your unit assessor (you are unlikely to meet anybody with the title of "professor" during your time in the Lantana League) will refer you to the appropriate Powerpoint slides for revision. Lantana League vice chancellors, in touting technology as a replacement for academic staff and campus facilities, are fond of noting that their students overwhelmingly prefer downloading lectures to attending them. This is approvingly dubbed "voting with their feet". There may be some truth to that, but it is also true that by their second year many students have realised that there is not a lot of point in downloading lectures, either. I know of some who record and listen to their own crib notes, in preference to the university-supplied recordings. You might call this "voting with their brains".

[I'm archiving for posterity a few articles I wrote for a now-defunct website. This is the second; here is the first.]

The typical recitation will involve someone who evidently intensely dislikes public speaking "umm"-ing and "err"-ing their way through slides which may have been hastily reviewed that morning in preparation, occasionally losing their place, or stopping to apologise for how boring the subject matter is. This is not to criticise these members of staff. This style of presentation is entirely in line with the institutional agenda, and is what is expected of them. The subject matter should be dismissed as boring, and each activity in the course of one's studies must be a bitter pill to swallow, otherwise the credential would not count as an accurate measure of dedication to one's career aspirations. To enjoy your time at university, or find your chosen discipline interesting, would be positively perverse.

Each assessment task is accompanied by a detailed marking rubric, examples of past work, a generous quantity of notes, tips, reference material, and so on. The marking rubric ensures that academic staff have no latitude to exercise their own judgement in grading, thus reducing the act of assessment to a mindless box-ticking exercise, and reducing the staff to interchangeable (and disposable) work units. For the student, it also reduces the task of doing the work to a similarly mindless process of reverse engineering from the material dropped in the student's lap.

Most courses can thereby be reduced to an empty charade of going through the motions; a pantomime education.

This is not to say there are no avenues for dissent. There are multiple administrative branches of any Lantana League university that are most eager to hear you rat out an individual member of the academic staff for providing insufficient "student satisfaction". However, if your criticism bears on the shallow, commercialised nature of the institution, there is an artificial mosquito breeding pond conveniently located on campus for you to go jump in.

This spoon-feeding of weak and enfeebling learning outcomes is justified by recourse to the increased socioeconomic equity of a system that is able to welcome "less academically-prepared students". In principle, I am one of those students who can boast of being the first in their family to attend university. However I have no desire to go to university merely for the purpose of vocational training.

My father received a great deal of vocational training in his progression from apprentice to tradesperson to management, and every cent (well, every penny initially) of the cost of that training was paid for by his employer. While on paper university enrollments have increased dramatically over the last 25 years, the real aim of that expansion, and the corresponding employment "credential creep", has been the imposition of a sadistically regressive tax, known as the Higher Education Loan Programme (HELP), which shifts a substantial portion of the cost of business (i.e. training, not to mention R&D) from employer to employee. As a side effect, unscrupulously entrepreneurial university administrators, and soon perhaps private for-profit training providers, do very well for themselves. Access to the kind of university education recognisable from the prime minister's student days remains as remote as ever for most Australians.

So for the foreseeable future of the Lantana League system, now that the eradication of "study of" in favour of "study for" is nearly complete, students outside the elite institutions have no hope of acquiring through university study a clear understanding of the world around them, nor the ability to actively participate in that world, or - heaven forbid - the will and means to consciously change it. Cheers.

An Introduction to the Self-Hating University

[I'm archiving for posterity a few articles I wrote for a now-defunct website. This is the second, from February 2014; here is the first, and the third.]

Distance learning just isn’t worth as much as on-campus tuition. That’s the opinion of Professor Jim Barber, vice-chancellor of the University of New England and self-satirist of note; or at least that’s what his opinion appears to be if one engages in a little speculative reading between the lines. He has just announced his intention to charge significantly less for online than on-campus courses. Moreover, in a stroke of breathtaking audacity, the money foregone will not be lost from the UNE administrative budget, and certainly not from executive salaries; Professor Barber is taking it from his students. From 2014, external students undertaking distance education will be exempt from the Students Services and Amenities Fees (SSAF). As for the subsequent defunding of student services, well tough luck.

“University students around the country are increasingly voting with their feet and not showing up to class,” says Barber, while making the very cuts that will make showing up to class even less desirable, “yet we continue to slug them for our services whether they use them or not. This is a pretty inefficient way to run any enterprise let alone a service industry.” (University of New England, 2013).

Barber proclaimed at a conference last year that “unbundling” is “where best practice is heading pedagogically. MOOCs [Massively Open Online Courses] are an extreme example in a bigger movement towards unbundling of services. Excellence in the business of higher education will increasingly mean individualised levels of service delivery, so pay for what you want and as you go.” (Streak, 2013).

Even before one begins to speculate over the prospect of pay-as-you-go lavatories for the recklessly profligate micturators on campus, it may seem extraordinary that a v-c would explicitly boast that his own institution deliberately aims to be the no-frills Ryanair of the higher education “service industry”. Nevertheless he maintains that “while most traditional universities around the world continue to press their governments for more funding, UNE is trying to move in the other direction.” (University of New England, 2013). UNE's staff and students just aren't worth the money, according to Professor Barber, and such naked contempt for students and staff alike is not as rare among university administrators as you might think.

In the US, San Jose State University has been leading this allegedly inexorable unbundling by outsourcing course delivery to proprietary MOOC providers. When asked whether this might lead to a decline in the quality of the education his students receive, SJSU's president merely deadpanned “It could not be worse than what we do face to face.” (Bady, 2013).

Such disdain for the practices of “traditional universities” is common throughout the world wherever Thatcherite principles of governance have taken hold. The “self-hating state”, to use George Monbiot's incisive term, “renounces its powers. Governments anathematise governance. They declare their role redundant and illegitimate. They launch furious assaults upon their own branches, seeking wherever possible to lop them off.” (Monbiot, 2013). It is therefore hardly surprising that when the self-hating state determines the regulatory environment in which universities operate, the state's attributes are reproduced in the self-hating university.

As Simon Marginson (2013) observes, the self-hating Australian government “prefers automatic economic mechanisms that remove the need to make and defend arguable policy positions”. In its turn the self-hating Australian university disavows any intrinsic purpose or values, and therefore any responsibility for the social consequences of its operations. It is merely a commercial service provider - shapeless clay to be moulded by the economically rational student-customer to suit their interests.

Two policy pumps maintain this pedagogical vacuum: Income-Contingent Loans (ICLs), and the Demand Driven Model (DDM). These and/or similar mechanisms pertain to an increasing number of other countries; the differences between them are interesting, but arguably increasingly marginal, so for simplicity the Australian example will be taken as broadly representative.

The pioneering implementation of Income Contingent Loans was Australia’s Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS). It was adopted in 1989 as a resolution to the tension between greater participation in higher education (spurred in part by the abolition of tuition fees in the 1970s), and the Hawke/Keating Labor government’s “considerable fiscal parsimony”, to quote the charmingly diplomatic chief architect of HECS, Bruce Chapman (1997).

To be politically palatable, HECS necessitated a reframing of public education as an individual good rather than a social good. In this way it could be argued that public funding of higher education is a form of progressive taxation: If, broadly speaking, the better educated are the better paid, it is unfair to tax the poor to fund the rich. To the counter-argument that higher education is an important way for the poor to improve their lot in life, “HECS' defining feature - income contingent repayment” (Chapman, 1997) appeared to be the perfect have-your-cake-and-eat-it rejoinder.

Indeed many commentators have marvelled at the “elasticity” of tuition pricing wherever income contingent loans are available, particularly in the wake of the unprecedented tuition hikes of 2010 in the United Kingdom. But in the Australian Universities’ Review, Emory McLendon (1997) posited a persuasive explanation for the ease with which students transitioning from high school to university accept the prospect of deferred fees: “The key word is deferred and the key factor is being 18 years old. […] A young student would tend to view the deferred payment of HECS in a similar light as a superannuation payout. It is simply too far into the future to be of great concern.”

Rachel Wenstone, vice-president of the UK National Union of Students suggests another explanation for demand-side price elasticity and “increased participation”, even in the face of the 2010 tripling of tuition fees: “With more than a million young people unemployed in the UK, some may feel like their options are somewhat limited and that choosing a situation which involves huge debt is the only way to enhance their employment options.” (Garner, 2013).

Nonetheless, consensus on tuition price elasticity is far from universal. In response to sectoral labour market shortages in the mid-nineties, the incoming Howard government introduced a tiered fee structure, with the intention that the price differential between disciplines would offer an incentive for students to enter those professions with the greatest demand for new skilled labour. Bruce Chapman was appalled. Recall that his scheme was designed to recoup the cost of higher education along economically rational, user-pays, free market lines. In his eyes, these changes were “not coherent, nor […] based on a well-defined set of economic principles” and charging inexpensively-trained lawyers more than expensively-trained nurses was “arguably poor economics” (Chapman & Nicholls, 2013). A genuine free market ideologue would sit back and allow the wages of nurses to rise in response to demand. Of course, to the nominal free market ideologues in government, the overriding principle is that free markets are fine for the plebs, but when the interests of employers are threatened, the free market can go fly a kite. Chapman clearly missed the memo.

While proponents of a commercialised higher education system point to growing participation rates in recent decades as a measure of its beneficial effects (at least on employment prospects), it is far from clear whether and to what degree this is the case. Longitudinal studies of the long-term effects of university study on either the individual or society are virtually impossible to use as a basis for policy prescription when the university is in a state of constant crisis and reinvention. The benefits that have accrued to the graduate of a generation ago cannot reasonably be assumed to apply to the graduate of today’s radically changed system.

To anybody involved in higher education prior to the reintroduction of tuition fees, the suggestion that one might attain a Bachelor of Business in Convention and Event Management, that economics would be taught as a component of business studies rather than vice versa, or that publicly funded universities would be teaching rank pseudoscience, would be considered laughable. However vocationalism and a business-centric view of the world is a logical consequence of user-pays tuition with a primary focus on financial return on a student’s “investment”.

Outside the small number of elite institutions that carry on the task of educating a privileged few, the majority of universities have embraced the pursuit of the “three Ms” of New Public Management (NPM): markets, management, and measurement. Lee Parker (2013) identifies this as “a clear example of goal displacement, whereby the financial resourcing of university missions and operations has become the end in itself.” Far from freeing each university to develop a unique character, and providing incentives for higher education to diversify and specialise, the result of commercialisation is quite the opposite. “Operating in a global marketplace and reflecting NPM, universities inevitably converge, presenting often-times homogeneous brands, missions, product and service offerings, and general organisational profiles.” (Parker, 2013)

Even so, you may ask, isn’t it undeniable that student-consumers are indeed “voting with their feet”, and that there must be some degree of declining demand behind the oft-repeated claim that there is a “crisis in the humanities”? As noted above, the apples vs. oranges obstacle to meaningful comparison of today’s universities to those of a generation ago makes quantifying any such effect problematic, and formal research with the aim of critically evaluating this contention is thin on the ground. American statistician Nate Silver recently dipped his toe into the quagmire and has tentatively concluded that “the relative decline of majors like English is modest when accounting for the increased propensity of Americans to go to college. In fact, the number of new degrees in English is fairly similar to what it has been for most of the last 20 years as a share of the college-age population.” (Silver, 2013). While this may be seen as some comfort to proponents of traditional academia, the more troubling corollary of this observation is that it seems quite likely that the liberal (indeed liberating) education that one would have expected to receive at university a generation ago remains just as much the preserve of elites as ever.

That the much-lauded increased participation in higher education, and avowed concern for students of “low socioeconomic status” (SES), is principally directed towards addressing the skilled labour requirements of industry brings to mind an adage from Earl Shorris, founder of the Clemente Course in the Humanities: “the poor are so often mobilized and so rarely politicized.” (Shorris, 1997). As Noam Chomsky notes, self-funded education is “one important way to implement the policy of indoctrination of the young. People who are in a debt trap have very few options.” (Chomsky, 2011). The combination of tuition fees and student loans effectively serves as a sin tax on the kind of education that produces politically empowered human beings rather than docile employees.

References

- Bady, A. (2013). The MOOC Moment and the End of Reform. Retrieved from http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/zunguzungu/the-mooc-moment-and-the-end-of-reform/

- Chapman, B. (1997). Conceptual issues and the Australian experience with income contingent charges for higher education. The Economic Journal, 107, 738–751.

- Chapman, B., Nicholls, J. (2013) Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS). Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies (APPS) Working Paper Series 02/2013, May 2013.

- Chomsky, N. (2011). Academic Freedom and the Corporatization of Universities. [Lecture transcript]. University of Toronto, Scarborough, April 6, 2011. Retrieved from http://chomsky.info/talks/20110406.htm

- Garner, R. (2013). Tuition fees no object: Record numbers of students enrol at UK universities. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/student/news/tuition-fees-no-object-record-numbers-of-students-enrol-at-uk-universities-9013696.html

- Marginson, S. (2013) Labor’s failure to ground public funding. Tertiary Education Policy in Australia. Centre for the study of Higher education, University of Melbourne.

- McLendon, E. (1997). HECS and the farmer’s son. Australian Universities' Review, 20(1), 4.

- Monbiot, G. (2013). The Self-Hating State. Retrieved from http://www.monbiot.com/2013/04/22/the-self-hating-state/

- Parker, L. D. (2012). From Privatised to Hybrid Corporatised Higher Education: A Global Financial Management Discourse. Financial Accountability & Management, 28(3), August 2012, 0267-4424

- Shorris, E. (1997). As a weapon in the hands of the restless poor. (On the Uses of a Liberal Education). Retrieved from http://clementecourse.org/docs/restlesspoor.pdf

- Silver, N. (2013). As More Attend College, Majors Become More Career-Focused. New York Times. Retrieved from http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/25/as-more-attend-college-majors-become-more-career-focused/?partner=rss&emc=rss

- Streak, D. (2013). Speakers' comments from regional universities conference. Retrieved from http://www.run.edu.au/cb_pages/news/conference_speakers_comments.php

- University of New England. (2013). UNE unbundles Student Services and Amenities Fee. Retrieved from http://blog.une.edu.au/news/2013/12/06/une-unbundles-student-services-and-amenities-fee/

The Humpty Dumpty University

[A couple of years ago, I started a website called UniAdversity to track the decline of higher education under neoliberalism. Within about a year, I found that there was far too much material for one person to keep abreast of, and my efforts to nonetheless do so meant I never had the time to recruit co-editors to share the load, so I simply gave up (if you're interested in helping to revive the site, let me know). There were a few pieces I wrote that are worth archiving publicly — at least if you're a fan of sledgehammer sarcasm — and this is the first of them, from November 2013; here is the second, and the third.]

In 2013, Southern Cross University (SCU) very quietly made the decision to stop offering Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Social Science degrees at its Coffs Harbour campus. The move went unremarked upon in what passes for the local media and, among staff and students at the university, was widely assumed to be a consequence of recent federal funding cuts, combined with a pre-existing executive antipathy to non-vocational subjects and the decidedly unglamorous Coffs campus. A look at the institutional pressures behind this ostensibly minor decision, in a satellite campus of a regional university, reveals that the 21st century university, in this country and elsewhere, is suffering an identity crisis. The long-term consequences of a higher education system that disavows its fundamental reason for existence may be considered out of scope for that system's managerial elite, but are for the rest of us already proving to be nothing short of catastrophic.

In 2013, Southern Cross University (SCU) very quietly made the decision to stop offering Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Social Science degrees at its Coffs Harbour campus. The move went unremarked upon in what passes for the local media and, among staff and students at the university, was widely assumed to be a consequence of recent federal funding cuts, combined with a pre-existing executive antipathy to non-vocational subjects and the decidedly unglamorous Coffs campus. A look at the institutional pressures behind this ostensibly minor decision, in a satellite campus of a regional university, reveals that the 21st century university, in this country and elsewhere, is suffering an identity crisis. The long-term consequences of a higher education system that disavows its fundamental reason for existence may be considered out of scope for that system's managerial elite, but are for the rest of us already proving to be nothing short of catastrophic.

What’s so bad about cutting a couple of under-enrolled courses from one campus? Let us first consider whether the loss is necessary in the first place. Isn’t the problem merely one of fundraising? One source of funding has been lost, but there’s no reason why another can’t be found. Whenever I put this argument to staff and students at SCU, the near-unanimous response was that the university is simply not interested allocating resources to the humanities, or to the Coffs Harbour campus. Vocational courses attract far more students, and resources are either being centralised at the Lismore campus, or sent north to the sexy new Gold Coast campus. The gloomy consensus is that SCU Coffs is being deliberately bled to death, and this year’s funding cuts have merely provided a pretext to hasten the process. I’m as cynical as the next man, provided the next man is Machiavelli, but even to me this sounded somewhat extreme. Not wanting to rely on speculation, however well informed, I decided to ask SCU’s vice chancellor, Professor Peter Lee.

“Let us say, hypothetically, that it were possible to find a source of funding to offset the Gonski cuts, or one or more partnering institutions were willing to participate in the provision of on-campus courses,” I suggested via email. Were this the case, what would be the likelihood of SCU “contributing towards the provision of face to face, university level education in the arts or social sciences in the Mid North Coast Region at any point in the foreseeable future?”

With a breezy shamelessness that points to a bright future in politics, the VC very kindly answered a completely different question of his own choosing: “We constantly evaluate demand for our programs (both new and existing courses) and to date, the demand has not justified an expansion of humanities programs at Coffs Harbour,” he replied.

“Demand” is the concept that cries out for scrutiny here. A greengrocer may decide to forego the provision of fruit and vegetables on the grounds of greater demand for coffee and sweets, but in doing so he forfeits the right to call himself a greengrocer (and also potentially accepts some responsibility for the subsequent local outbreak of scurvy). It would certainly not be appropriate to pronounce the provision of coffee and sweets to be the future of greengrocery, and to deride anybody who maintains that fruit and vegetables are still an important part of the trade as a nostalgic old hippie.

Furthermore, “demand” is not a synonym for “need”. Beyond government departments and market-driven university administration offices, there is general consensus on the role that universities are expected to fulfil. That fine source of inspiration for after dinner speakers, the Oxford English Dictionary, defines a university as “an institution of higher education offering tuition in mainly non-vocational subjects”. In contrast, from 2014, the bachelor courses available to students in Coffs Harbour are restricted to Business, IT, Education, Nursing, Midwifery, and Psychology.

The 1963 report of the Robbins committee on higher education, in delineating the responsibilities of the UK university system, emphasised promotion of the “general powers of the mind”, to produce “not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women”. By insisting that the primary purpose of a university is to provide vocational rather than academic education, and to meet market demand rather than social need, SCU is, in the manner of Lewis Carrol's Humpty Dumpty, maintaining that the word university “means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less”.

The 1963 report of the Robbins committee on higher education, in delineating the responsibilities of the UK university system, emphasised promotion of the “general powers of the mind”, to produce “not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women”. By insisting that the primary purpose of a university is to provide vocational rather than academic education, and to meet market demand rather than social need, SCU is, in the manner of Lewis Carrol's Humpty Dumpty, maintaining that the word university “means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less”.

“Southern Cross University does not intend and never has attempted to emulate other universities”, its website declares. “We aim to become the most progressive and innovative regionally based university in Australia - and we are well on the way to achieving that aim.” That is, by redefining what it means to be a university. Twenty years ago, as part of the Dawkins Revolution, the (vocational) Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education became Southern Cross University. Now it is coming full circle, back to specialising in qualifications “designed in consultation with industry […] to produce work-ready graduates.”

For those students who aspire to more than work-readiness, the quaint vestiges of the humanities at Coffs Harbour are still available via distance education. As it happens, demand is not so much of a problem when you can make what you're supplying cheap enough. Cheap, that is, for the university to provide; the fees borne by the student and the public purse remain the same. One might conclude that the students who are of no use to the modern commercial university's partners in industry are being fobbed off with third-rate correspondence courses, but in some quarters it is contended that they are actually the fortunate pioneers of higher education's coming cyber-utopia.

According to Professor Jim Barber, vice chancellor of the University of New England, “The nation has invested, and continues to invest, billions of dollars in […] classrooms, laboratories, libraries, student accommodation and buildings of various kinds under the assumption that it is necessary to duplicate all of this infrastructure around the country if Australian students are to receive the best education possible.” However, “Massively Open Online Courses” (MOOCs) “demonstrate that much of this capital expenditure is unnecessary and that this generation of vice-chancellors really ought to stop lumbering their university balance sheets with superfluous lecture theatres and burdensome depreciation costs.”

Moreover, by offering courses at no cost, “MOOCs merely confirm what we’ve known for years—that the most basic currency of universities, information, is now more or less valueless,” according to the Professor, who apparently sees no distinction between value and price, and for whom “universities really only have one saleable product—a credential.”

If the university of the future has a campus at all, “it will not be because they provide the best or most efficient means of educating people but because some individuals will always want to 'go to a university' in order to hang out with friends” - if you can imagine such a thing! The more efficient majority of students will instead eschew “bricks and mortar” to “live and move, interact and experiment in a network cloud”.

“Virtual environments are emerging that mimic the real world and provide us with a visceral sense of immersion. Some have even argued that the distinction between virtual and material will disappear altogether. This is because all surfaces, including the skin, are potential interface points enabling users to issue and receive computer commands using their own body parts as touchpads.”

I am not personally acquainted with the systems (or perhaps psycho-active substances) that Professor Barber uses when issuing these breathless prophesies from his corner of the network cloud, but I can say for certain that the system his students (like those of SCU) are compelled to use is the clunky and much derided Blackboard Learning System, which is more closely related to the early online bulletin board systems of the 1980s than to the Star Trek holodeck. It is true that there are some quite compelling virtual environments already in existence. These are very well suited to pursuing aliens, zombies, or dark-skinned foreign people, and dispatching them with a hand-held rocket launcher, but utterly excruciating when attempting any more nuanced interaction.

So if we can't afford bricks and mortar, and our unsociable but efficient students don't want it anyway, how do we fund the construction of the dermatologically-interfaced cyber-campuses of Professor Barber's fevered imaginings? Fortunately it turns out that higher education isn't as cash strapped as one might suppose. The new federal Minister for Trade and Investment, Andrew Robb, points out that education is actually “Australia's fourth largest export, behind iron ore, coal and gold, and last year it had student enrolments of more than 500,000, earned $15 billion in revenue, and employed more than 100,000 people.” This is why his department, along with a consortium of universities and their omnipresent partners in industry, have launched the “Win Your Future Unlimited” competition to lure more full-fee-paying student-customers to Australia.

According to the competition website, “Seven finalists will be flown to Australia for a study tour. And one finalist will win the major prize – a year of study in Australia, including flights, tuition, accommodation, and much more.”

It's tempting to jump to the cynical prediction that before long some lucky boy or girl will find an Australian Ph.D. in their box of Corn Flakes, but there are additional layers of subtlety to this initiative. “The basic idea,” says Robb, “was to shift the focus away from Australia's lifestyle and natural beauty as points of attraction for students to one emphasising the ways in which study in Australia can help fulfil career ambitions through a quality education.”

Wait a moment. “Quality education”? Surely nobody wants that any more? A credential is sufficient to demonstrate work-readiness, and efficiency demands that we minimise the amount of education involved in getting it. And why would anybody want to be dragged around the country touring a lot of fusty old bricks and mortar, much less spending a whole year in such a place? Surely the efficient winning student would much prefer to stay at home in his underpants and enjoy the “visceral sense of immersion” in watching a dimly-lit, near-inaudible video recording of an overworked casual teaching assistant in Lismore joylessly ploughing her way through a PowerPoint slide deck?

Of course the truth is that very few students, given the option, would spurn a Robbins-era liberal education in favour of logging on to the post-Dawkins vocational credential delivery system. The former holds the promise of producing a finer, more sophisticated, fuller human being, and prepares one for an infinity of potential futures; perhaps a celebrated life of grand artistic achievement, or selfless public service, or a cosy directorship at the BBC hob-nobbing with the Davids Attenborough, Frost, and Dimbleby. The latter gets you a cubicle at the call centre next to Dave, a gormless teenaged backpacker from Aberystwith.

Setting aside the personal ambitions, or lack thereof, of our students, is there any major harm to society in reserving real education for a cashed-up global elite who can afford to shop for sandstone, while the majority of students in less august institutions pursue courses in lower education designed by and for business?

Eminent economist Ha-Joon Chang, currently teaching at Cambridge, has noticed the effect of narrow, vocationally focussed curricula on economics students, and is alarmed to find that few “know what is going on in China and how it influences the global economic situation. Even worse, I've met American students who have never heard of Keynes.” (Inman, 2013). These students may have no idea what caused the 2008 economic crisis, or perhaps even that there was one, but they do have a solid command of the mathematics that allows them to play successfully in the global casino economy on behalf of their employers in the City of London.

Closer to home, one might question the value of producing “work-ready” graduates in Coffs Harbour, a place with a very high degree of unemployment, under-employment, and tenuous employment, and with one of the country's greatest gulfs between income and cost of housing. Surely it would be more fruitful to produce graduates capable of investigating, analysing, and solving such problems? Or perhaps the method behind the university's apparent madness is a version of Say's law, a particularly potty notion that supply causes demand, and therefore if you supply the cubicle drones, the cubicles will follow. (However, given that the majority of the university's management will have graduated in the work-ready post-Dawkins era, it's unlikely that they will have heard of any such theory, as it isn't industrially relevant.)

A solid grounding in economics might also lead one to wonder what the long term consequences of a massive national program of vocational degrees promoted as a pathway to guaranteed employment might be, given that the promised employment largely does not exist. There is something oddly familiar about the prospect of overvalued assets purchased with cheap and easy credit by people with limited ability to repay. As British higher education analyst Andrew McGettigan notes, “Subprime degrees, like subprime mortgages, are sold to communities relatively unfamiliar with the product.” (Collini, 2013).

Professor Simon Marginson, of the University of Melbourne’s higher education faculty, writes “If higher education is emptied out of its public purposes we can no longer justify its survival. Today’s higher education institutions need a larger purpose that underpins their existence, a purpose that is more than a marketing slogan. The 21st century university needs to redefine itself as a creator, protector and purveyor of public goods.” (Marginson, 2013). For this to happen, the responsibility lies with students and academic staff to reclaim their universities from managers and marketers.

At the University of Manchester last year, a group of economics students found themselves increasingly frustrated with a course that, in the words of a university spokesman “focuses on mainstream approaches, reflecting the current state of the discipline” because such a blinkered view is “important for students' career prospects”, even if it teaches them nothing about how the world beyond the finance industry actually works (Inman, 2013). In response they instituted the Post-crash Economics Society, which seeks to “provoke discussion between students and staff about what economics is, what it should be and how it should be taught”.

These students have been echoing, although they didn’t know as much at the start, an earlier decades-long struggle led by students and staff at the University of Sydney, which finally culminated in the establishment of the university’s Department of Political Economy, now one of the world's most respected and vibrant centres of academic enquiry in economics.

Just as economics can be retrieved from business studies, so we can rescue the arts from the study of the creative industries. Perhaps we can also once again learn from history. Or even revive philosophy, the august and ancient progenitor of academia, long neglected and even scorned by the disciples of vocationalism and credentialism, who proclaim their devotion to the real world while condemning all of us to a toxic fantasy of their own making. As students and academic staff at university, even at the market-driven university, we occupy positions of substantial privilege. We therefore owe it to our society to reform our institutions to serve society’s needs, because we know the difference between need and demand, and between price and value, and we know what the word “university” means.

References

Barber, J. (2013). The end of university campus life. Ockham's Razor.

Collini, S. (2013). Sold out. London Review of Books, 35(20).

Inman, P. (2013, October 25). Economics students aim to tear up free-market syllabus. The Guardian.

Marginson, S. (2013). The modern university must reinvent itself to survive. The Conversation.

Robb, A. (2013). Education geared for growth.

Sunday, 21 February 2016 - 11:51am

This week, I have entirely caught up on 2015! Next week will be January and February 2016, before uni starts the week after.

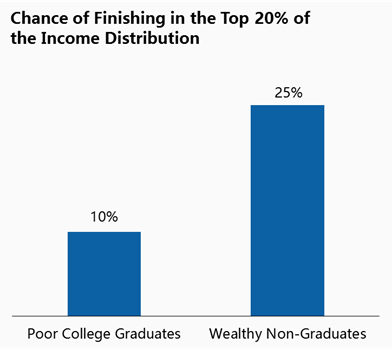

- ‘On the first day of Christmas, my true love gave to me’ … a bunch of econ charts! — Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg in the Washington Post. My pick of these:

- The Melting Away of North Atlantic Social Democracy — Brad DeLong in Talking Points Memo:

Supply-and-demand tells us that when the economy's wealth-to-annual income ratio varies, the rate of profit should vary in the opposite direction. But history tells us that the rate of profit sticks at 5% per year, across eras with very different wealth-to-annual-income ratios. Piketty, however, does not tell us why. Perhaps this is because at a technological level capital does not empower and complement but rather competes with and thus substitutes for labor. Perhaps this is because of successful rent-seeking by the rich who control the government and get it to award them monopoly rents. Perhaps it is because of a social structure that leaves wealth holders believing that a 5% per year is the "fair" rate of profit and are unwilling to underbid each other.

- The road to the workhouse — Frances Coppola is rightly outraged by punitive sanctions imposed on UK benefit claimants:

The workhouse ethic was that work is a moral imperative: people who have no work are morally defective and must be forced to work as a "correction". If they refuse to work, they must be severely punished. The DWP's sanctions regime looks uncomfortably similar. The sick, disabled, mentally ill and unemployed are treated like criminals even though they have committed no crime. A strict penal regime is imposed on them, with extremely harsh punishments for minor transgressions of unfair and arbitrary rules. These punishments affect not only their own health but the health of those dependent on them. Not unlike workhouses, really.

- AIPE: 8000 students in limbo as Sydney college has its registration cancelled — Eryk Bagshaw, Sydney Morning Herald:

A former student of the college, Helen Fielding, told Fairfax Media she was coached over the phone by agents to sign up for a $19,600 diploma of Human Resources Management. The 21-year-old grew up in foster care and has an obvious intellectual disability. "I'm not good at reading," she said at her housing commission flat outside Newcastle.

- Home is where the cartel is — Steve Randy Waldman:

If you buy a home in San Francisco today, the last thing you want to happen is for the housing affordability problem to be solved next year. If apartment prices become reasonable, you’d find yourself with a huge financial loss and an underwater mortgage. […] High rents are like poverty at the Brookings Institution, a problem we claim we desperately want to solve but don’t really want to solve because the things we would have to do to solve it would be costly and disruptive to the people whose interests get termed “we” in a sentence like this one.

- The Sneaky Way Austerity Got Sold to the Public Like Snake Oil — Lynn Parramore of the Institute for New Economic Thinking interviews Orsola Costantini of same:

How do we stop powerful players from co-opting economics and budgets for their own purposes? Our education system is increasingly unequal and deprived of public resources. This is true in the U.S. but also in Europe, where the crisis accelerated a process that was already underway. When children don’t get good educations, the production of knowledge falls into private control. Power gets consolidated. The official theoretical frameworks that benefit the most powerful get locked in.

- Why Philanthropy Actually Hurts Rather Than Helps Some of the World’s Worst Problems — George Joseph, In These Times:

Zuckerberg can legally offer the bulk of his "philanthropy" to any for-profit recipients he wants and still receive public acclaim for "gifting" his fortune. We're seeing the rise of a new, horizontal philanthropy - the rich giving directly to the rich - at a level that's completely unprecedented.

- It's official — benefits and high taxes make us all richer, while inequality takes a hammer to a country's growth — Lee Williams, the Independent:

Thanks to the OECD report, we find that the very thing that the sacrifices of austerity were made to preserve – the growth of the economy – is the very thing they are destroying. Neo-liberal, laissez-faire capitalism extends inequality, we already knew that. But now we have the evidence that inequality harms, rather than encourages growth.

- 'Free Basics' Will Take Away More Than Our Right to the Internet — Vandana Shiva, Common Dreams:

The Monsanto-Facebook connection is a deep one. The top 12 investors in Monsanto are the same as the top 12 investors in Facebook, including the Vanguard Group. The Vanguard Group is also a top investor in John Deere, Monsanto’s new partner for ‘smart tractors’, bringing all food production and consumption, from seed to data, under the control of a handful of investors. […] Smart Tractors from John Deere, used on farms growing patented Monsanto seed, sprayed and damaged using Bayer chemicals, with soil and climate data owned and sold by Monsanto, beamed to the farmer’s cellphone from Reliance, logged in as your Facebook profile, on land owned by The Vanguard Group. Every step of every process right up until the point you pick something up off a supermarket shelf will be determined by the interests of the same shareholders.

More here. - Why Are Universities Fighting Open Education? — Elliot Harmon at Common Dreams:

Though universities tout [patented] technology transfer as a way to fund further education and research, the reality is that the majority of tech transfer offices lose money for their schools. At most universities, the tech transfer office locks up knowledge and innovation, further expands the administration (in a sector that has seen massive growth in administrative jobs while academic hiring remains flat), and then loses money.

Monday, 15 February 2016 - 11:17am

Always liked that Turnbull fellow. Won't hear a word said against him.

I'm choosing to take this as a sign that things are looking up; that it's no longer sufficient to be a plutocratic ideologue and class warrior to have a hand in Australian public policy.

On the other side of the house, even Shorten appears to have located his spine, and is advocating the decades-overdue sunsetting of the parasitic speculator's best friend, negative gearing. In addition to the hitherto inconceivable possibility of a soft landing to the property bubble, Australia may be catching on to the spirit of democratic renewal that has made possible the rise to prominence of people like Sanders and Corbyn (not to mention, in very different circumstances, Podemos and pre-capitulation Syriza).

Good news for everybody who hasn't thrown in their lot with the crazies. Commiserations to the former Member for Tony Abbott.

Sunday, 14 February 2016 - 1:24pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- The Guantánamo in New York You’re Not Allowed to Know About — Arun Kundnani, The Intercept:

Mahdi Hashi, a young man of Somali origin who grew up in London, had never been to the United States before he was imprisoned in the 10-South wing of the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan in November 2012, when he was 23. For over three years, he has been confined to a small cell 23 hours a day without natural light, with an hour alone in a slightly larger indoor cage. He has had no physical contact with anyone. Apart from occasional visits by his lawyer, his human interaction has been limited to brief, transactional exchanges with guards and a monthly 30-minute phone call with his family.

- Full employment is a tenet of classic social democracy – but is it still applicable? — Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams in the New Statesman:

While Jeremy Corbyn’s opponents have presented him as a throwback to an old-left style of politics, in fact he has been the only one to recognise the changed realities of the UK in the 21st century. Creating a mental health position in his shadow cabinet, questioning the utility of the Trident nuclear programme and NATO, calling for social support for the self-employed – all these reveal a politics that is very aware of contemporary Britain and its discontents. Meanwhile, his opponents’ prevailing thinking appears mired in the past: a cold-war fascination with obsolete security communities, fond nostalgia for the 1990s, and increasingly punitive attempts to create good workers when good jobs no longer exist.

- Trying to simulate the human brain is a waste of energy — Peter Hankins in Aeon:

It’s as though we decided to build a Tardis immediately, on the basis of the knowledge we have about it now – call it the ‘Blue Box’ project. We know it’s blue, squarish, probably uses electricity for some purposes, makes a whooshy noise, travels in time and is bigger on the inside; let’s get started! Of course, we have no idea how the last two things (the time travel and the strange geometry) are done, but then the brain also does things – subjective experience, intentionality, personhood, to name three – that currently seem to be beyond the reach of either science or philosophy.

- The Basic Income Guarantee: what stands in its way? — Tom Streithorst guestblogging for Frances Coppola:

Fear of scarcity is built into our DNA. For the Basic Income Guarantee to seem viable for most people, they need to learn that demand, not supply, is the bottleneck of growth. We need to recognise that money is something humans create, not something with fixed and limited supply. With Quantitative Easing, central banks created money and gave it to the financial sector, hoping it would stimulate lending. Today, even mainstream figures like Lord Adair Turner, Martin Wolf and even Ben Bernanke recognize that “helicopter drops” of money into individuals’ bank accounts could have been more effective. Technocrats are beginning to recognise the practicality of Basic Income. […] The Basic Income Guarantee solves the problem of demand, stimulates the economy, increases corporate profits, gives workers more freedom, and provides a safety net to the most vulnerable. It is economically sound and politically savvy. But the very rich don’t fear unemployment, they fear redistribution and they will be the most significant force against the implementation of the Basic Income Guarantee.

- The Fed Raises Rates--by Paying the Banks — Marty Wolfson in Dollars & Sense:

Under current Chair Janet Yellen, the Federal Reserve has shown a genuine concern about unemployment, but it is still trapped in its assumptions: There is a “maximum feasible” level of employment. Above that level (or below the corresponding rate of unemployment) inflation will exceed its 2% target. The conclusion from these assumptions is that the Fed should raise interest rates to prevent employment from exceeding the “maximum feasible” level. Instead, the Fed should adopt a real full- employment target: a job for everyone who wants to work. It should adopt a “minimum feasible” target for inflation: the lowest possible rate compatible with full employment. We need a policy perspective in which economic justice for workers is a higher priority than paying the banks.

- Working Paper: The Upward Redistribution of Income: Are Rents the Story? — Dean Baker from CEPR says yes:

This paper argues that the bulk of this upward redistribution comes from the growth of rents in the economy in four major areas: patent and copyright protection, the financial sector, the pay of CEOs and other top executives, and protectionist measures that have boosted the pay of doctors and other highly educated professionals. The argument on rents is important because, if correct, it means that there is nothing intrinsic to capitalism that led to this rapid rise in inequality, as for example argued by Thomas Piketty.

- Good things happen at full employment — Jared Bernstein in the Washington Post:

Dean Baker and I have long contended that at full employment, pressures from labor costs […] mean that firms either have to find new efficiencies, raise prices or start cutting into profit margins. Since they’d generally rather avoid the latter two, full employment can lead to higher productivity growth.

- A Missed Opportunity of Ultra-Cheap Money — Peter Eavis, NYT:

[William A. Galston, a former adviser to President Bill Clinton and now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution] in particular lamented the failure to set up a government-backed infrastructure bank in recent years. “This will go down as one of the great missed opportunities,” he said. Public investment spending as a share of overall economic activity has fallen to lows not seen since the 1940s, according to an analysis by James W. Paulsen of Wells Capital Management.

- Beyond social mobility — Chris Dillow:

A simple thought experiment will tell us that social mobility is nothing like sufficient. Imagine a dictator were to imprison his people, but offer guard jobs to those who passed exams, and well-paid sinecures to those who did especially well. We'd have social mobility - even meritocracy and equality of opportunity. But we wouldn't have justice, freedom or a good society. They all require that the prisons be torn down.

- CEO pay still out of control and diverging again from workers’ earnings — Bill Mitchell:

Two things caught my attention among other things last week. The Australian Tax Office (ATO) released the – 2013-14 Report of Entity Tax Information – which tells us about the total income and tax payable was for 2013-14 tax year for 1539 Australian and foreign companies operating in Australia with incomes above $A100 million. The rather startling revelation is that 579 of the largest Australian companies including Qantas did not pay any tax at all in that financial year. The second (unrelated but pertinent) report was released last week by the British Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) – The power and pitfalls of executive reward: a behavioural perspective – which found that the increasing gap between British CEO earnings and their employees is unrelated to company performance and reflects “self-serving tendencies”.

- Dear Parents: Everything You Need to Know About Your Son and Daughter’s University But Don’t — Ron Srigley in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

First, [sessional contract staff] are not scholars but employees. They think of administrators as people they work for rather than people who work for them by supporting their teaching and research. Second, they are vulnerable and therefore remain mostly silent about critical matters. If a sessional instructor complains publicly about her institution or its declining standards, she will do so only once. […] Finally, the very act of employing, empowering, and often elevating such people denigrates real scholars and scholarship by definition. If a person who knows next to nothing of what you know can do what you do just as well as you do it, then what is the value of what you know?

- Finland's hugely exciting experiment in basic income, explained — Dylan Matthews in Vox:

The idea is to see what happens to a community under a basic income, rather than just to individual people. Having a whole town get benefits could have cascading effects as households escape poverty, as some people use the income guarantee as insurance so they can take risks and form companies, as universities see increased enrollment from people better able to afford supplies, etc. "If people in a smaller area are getting the benefits, their behavior vis-a-vis other people will change, employers and employees will change their behavior, encounters between clients and their street-level bureaucrats (social workers, employment offices, etc.) will change, and the interplay between different bureaucracies will change," Kangas says.

- Love from mom and dad … but who gains from Mark Zuckerberg’s $45bn gift? — Linsey McGoey in the Guardian:

As if sensing that our newfound effervescence had fizzled rather abruptly, a crack team of management scholars and business journalists took up arms, manning airwaves and TV stations and the open-planned domiciles of new media startups funded by tech entrepreneurs based in Hawaii – and tried to cheer us with a single message. You’re right, they conceded. It’s not charity. But here’s the thing: it’s better than charity. It’s a new, radical movement that we like to call “philanthrocapitalism” – and it’s going to make you all rich. How, you might ask? By giving more philanthropy to the wealthy.

- The IMF Changes its Rules to Isolate China and Russia — Michael Hudson:

A nightmare scenario of U.S. geopolitical strategists is coming true: foreign independence from U.S.-centered financial and diplomatic control. China and Russia are investing in neighboring economies on terms that cement Eurasian integration on the basis of financing in their own currencies and favoring their own exports. They also have created the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as an alternative military alliance to NATO. And the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) threatens to replace the IMF and World Bank tandem in which the United States holds unique veto power.

- The world of threats to the US is an illusion — Stephen Kinzer in the Boston Globe:

I recently asked a United States Navy officer what threats he believed the United States might confront in the future. To my astonishment, he answered, “Venezuela.” The South American country is in political crisis and careening toward bankruptcy. Its combat navy counts six frigates and two submarines, none of them seaworthy. Yet last month President Obama designated Venezuela an “extraordinary threat to US national security.” The search for enemies can lead to odd places.

- Piketty and the Australian exception — John Quiggin at Crooked Timber:

Australia’s relatively equal distribution of income and wealth depends on a history of strong employment growth and a redistributive tax–welfare system. Neither can be taken for granted. […] The move towards a patrimonial society already happening in the US is evident at the very top of the Australian income distribution. As in the US, the claim that the rich are mostly self-made is already dubious, and will soon be clearly false. Of the top 10 people on the Business Review Weekly (BRW) rich list, four inherited their wealth, including the top three. Two more are in their 80s, part of the talented generation of Jewish refugees who came to Australia and prospered in the years after World War II. When these two pass on, the rich list will be dominated by heirs, not founders.

Thursday, 11 February 2016 - 1:39pm