Recession

How Are They Now? A Checkup on Homeowners Who Experienced Foreclosure

The end of the Great Recession marked the beginning of the longest economic expansion in U.S. history. The Great Recession, with its dramatic housing bust, led to a wave of home foreclosures as overleveraged borrowers found themselves unable to meet their payment obligations. In early 2009, the New York Fed’s Research Group launched the Consumer Credit Panel (CCP), a foundational data set of the Center for Microeconomic Data, to monitor the financial health of Americans as the economy recovered. The CCP, which is based on anonymized credit report data from Equifax, gives us an opportunity to track individuals during the period leading to the foreclosure, observe when a flag is added to their credit report and then—years later—removed. Here, we examine the longer-term impact of a foreclosure on borrowers’ credit scores and borrowing experiences: do they return to borrowing, or shy away from credit use and homeownership after their earlier bad experience?

Foreclosure Notations on Credit Reports

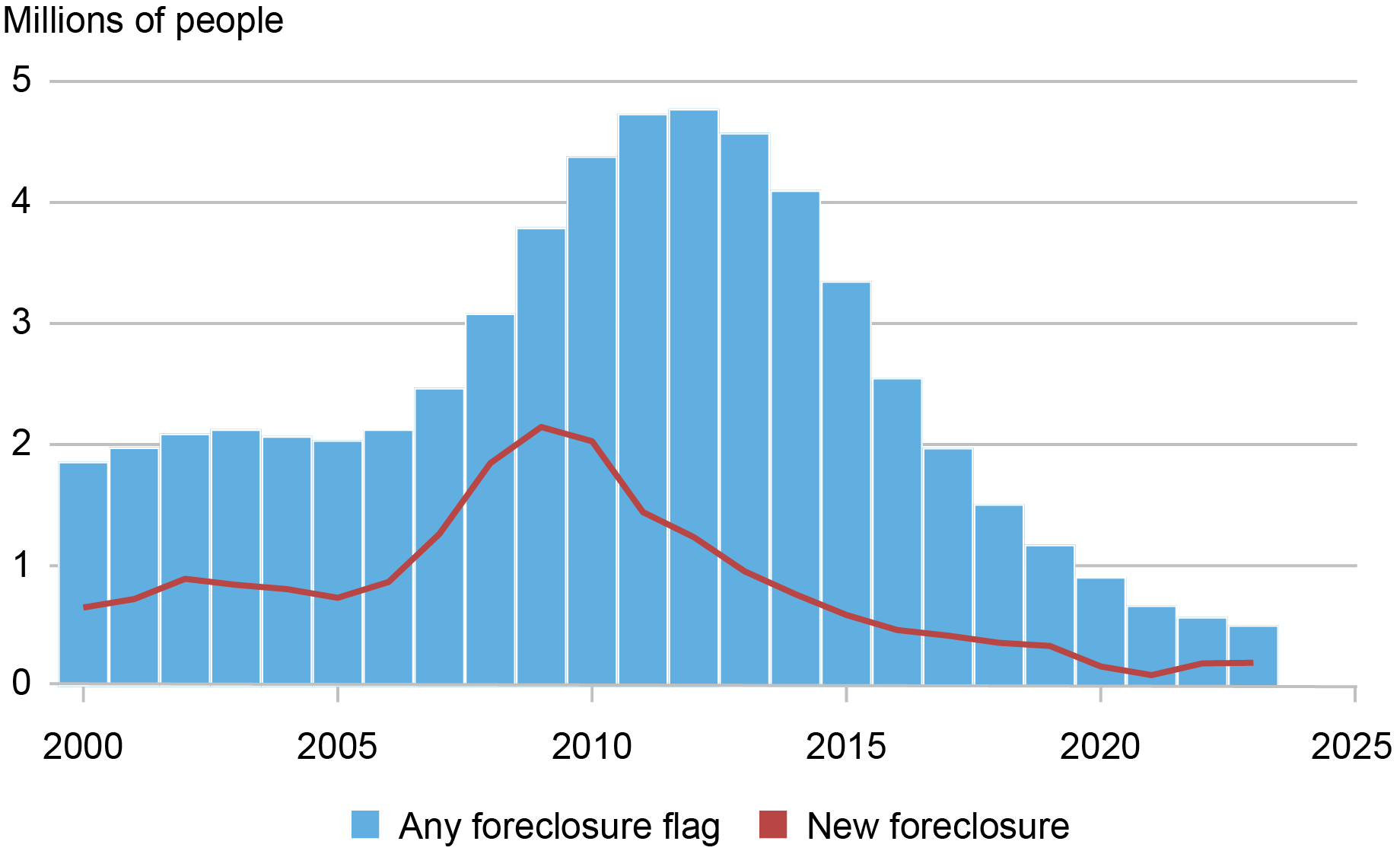

Foreclosures are associated with a flag on the credit reports of mortgage borrowers, which is similar to what happens after an individual files bankruptcy. Information related to foreclosures (“foreclosure notes”) may not remain on a credit report for more than seven years, as stipulated in the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). These negative notes on credit reports are visible to creditors and limit the borrowers’ access to credit by reducing their credit scores and enabling lenders to decide whether to lend to those who previously foreclosed. The FCRA guidance protects borrowers by providing a finite window during which their access to credit may be limited due to their past delinquency and default. Because they stick for seven years, the flags accumulated during the Great Recession were slated to remain for years after it ended. In the chart below, we show (in the red line) the number of consumers with new foreclosures observed each year. The blue bars show just how many people had a foreclosure note on their credit report; by 2016, the number of individuals with a foreclosure mark had finally begun to return to more normal levels as the flags aged off.

Foreclosure Marks on Credit Reports Were Rare by 2023

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Notes: Data are reported at an annual frequency.

Foreclosures reached record levels during the Great Recession. Between 2000 and 2006, there were, on average, under 700,000 foreclosures initiated annually. But between 2007 and 2013, that number more than doubled—we observe approximately 1.8 million foreclosures per year. The highest level was observed in 2009, with about 2 million new foreclosures initiated. The cumulative effect was 4.8 million consumers with a foreclosure note on their credit report by 2011.

Impact on Credit Score

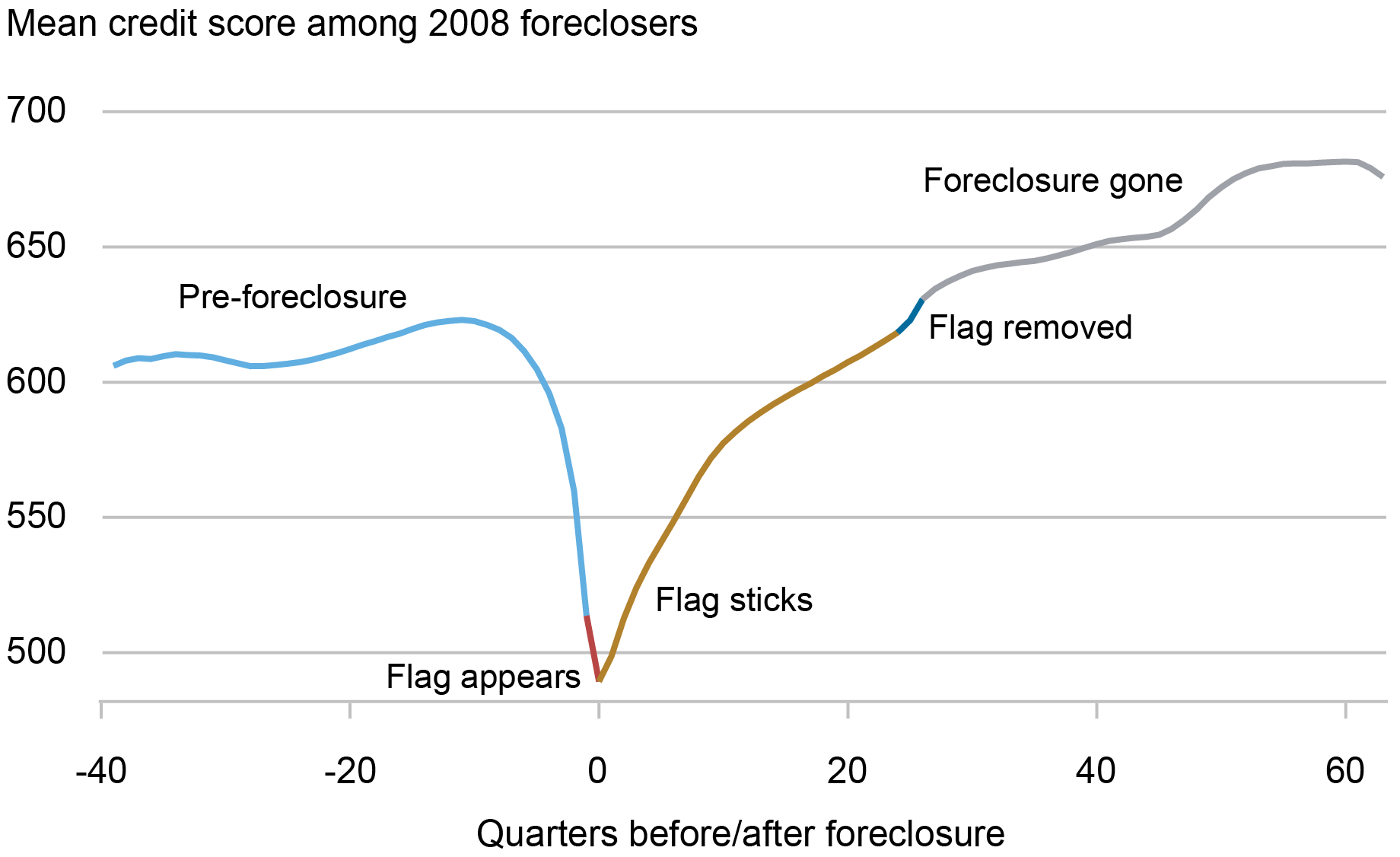

In the chart below, we look at the average credit score of the individuals who had a flag added to their credit report during 2008. Along the horizontal axis, we show the quarters before and after the flag was added, with zero being the quarter that the flag first appeared. The foreclosure note generally lasts for about twenty-six quarters, so one thing that’s visible in the chart is that the note itself isn’t necessarily what causes a borrower’s credit score to decline. The period of delinquency before the foreclosure starts results in a 150-point credit score drop on average and with an average score falling below 500; the addition of the flag itself is associated only with a small additional decline in the score. The average credit score steadily improves from that point as the foreclosure note ages, eventually increasing by an additional average of 20 points when the foreclosure note drops off.

Credit Score Declines before the Foreclosure Flag Appears

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Note: Credit score is Equifax Risk Score 3.0.

Longer Term, How Have These Borrowers Fared?

It is well-documented that foreclosures during the Great Recession were concentrated in certain parts of the country, such as the so-called “sand states.” We additionally find those who experienced foreclosure tended to be younger—in fact, over 41 percent of these borrowers were under 40 years old and had newly entered homeownership during the frothy early-2000s housing market. Homeowners who were foreclosed on in 2008 also tended to be disproportionately from lower-income zip codes; 41 percent of those who foreclosed in 2008 were from the lowest-income quartile that comprises 25 percent of the population and an even smaller share of the home-owning population.

This episode of serious financial distress occurred for many borrowers as they entered their prime working years, leaving a persistent scar on their credit reports. The flags would have fallen off the credit reports of those who experienced a 2008 foreclosure action by 2015, and 2023 marked an additional nine years since then. In the following section, we explore how these borrowers are faring now, and whether they’ve caught up to their peers who didn’t lose their homes.

Because most borrowers find themselves with deep-subprime credit scores after foreclosure, getting new credit is difficult. Borrowers ease into getting new loans about four years after getting a flag, which is on average about when their score approaches their pre-distress score. For this group, new mortgage borrowing in particular is very slow, partially reflecting tightened credit standards.

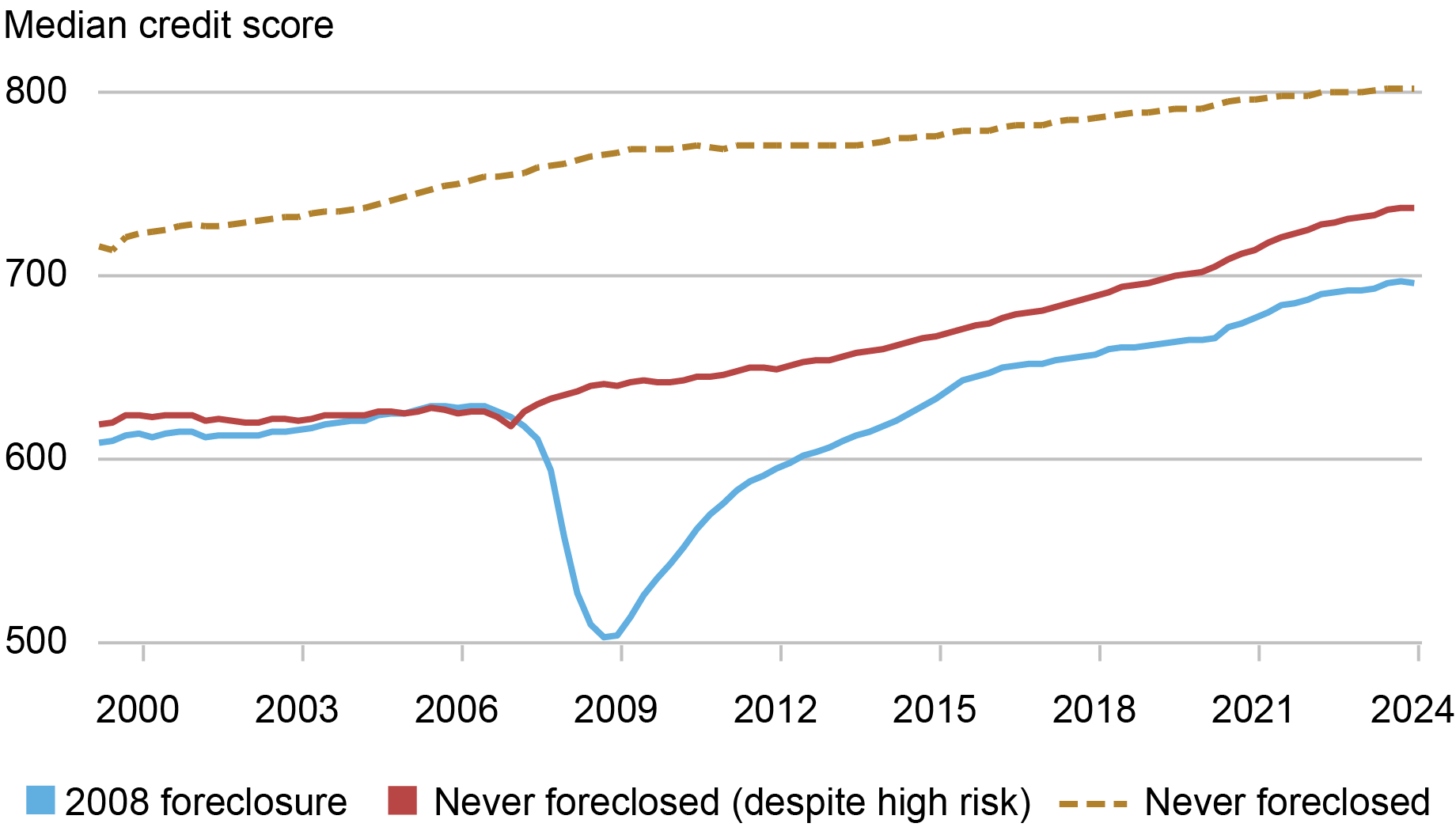

Because borrowers who experienced foreclosure tended to be different in measurable ways from the average mortgage holder, we create a comparison group for these borrowers by selecting 2008 mortgagors who never foreclosed, despite having similar characteristics that put them at a higher risk of foreclosing based on their age, credit history, and geographic location. This group might include, for example, a younger mortgage borrower who had a low credit score and lived in a lower-income area in 2005. The fact that they did not foreclose on their home in 2008 may have been because they were able to avoid job loss, or could rely on greater financial support from family or friends.

In the chart below, we depict the evolution of credit scores among those who foreclosed and similar borrowers who did not. We additionally provide the average credit score of the overall population of mortgage borrowers who did not experience foreclosure, shown in the dotted gold line. Notably, borrowers who did foreclose—shown in blue—have credit scores that were considerably lower than mortgage borrowers who never foreclosed even before the foreclosure event (dotted gold line), as subprime borrowers were a substantial share of the initial wave in 2008. Yet, when we compare these borrowers with the selected peer group, shown in red, we see that even sixteen years out, the gap between the median credit scores of these two groups, while substantially narrowed, has remained persistent. And when we compare these borrowers to the 2008 mortgage borrowers who never foreclosed, we see that, despite an overall improvement in credit scores with age, there continues to be a significant gap between their median credit scores.

Foreclosed Borrowers’ Credit Scores Rebound, but Have Not Caught Up to Peers’

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax

Note: Credit score is Equifax Risk Score 3.0.

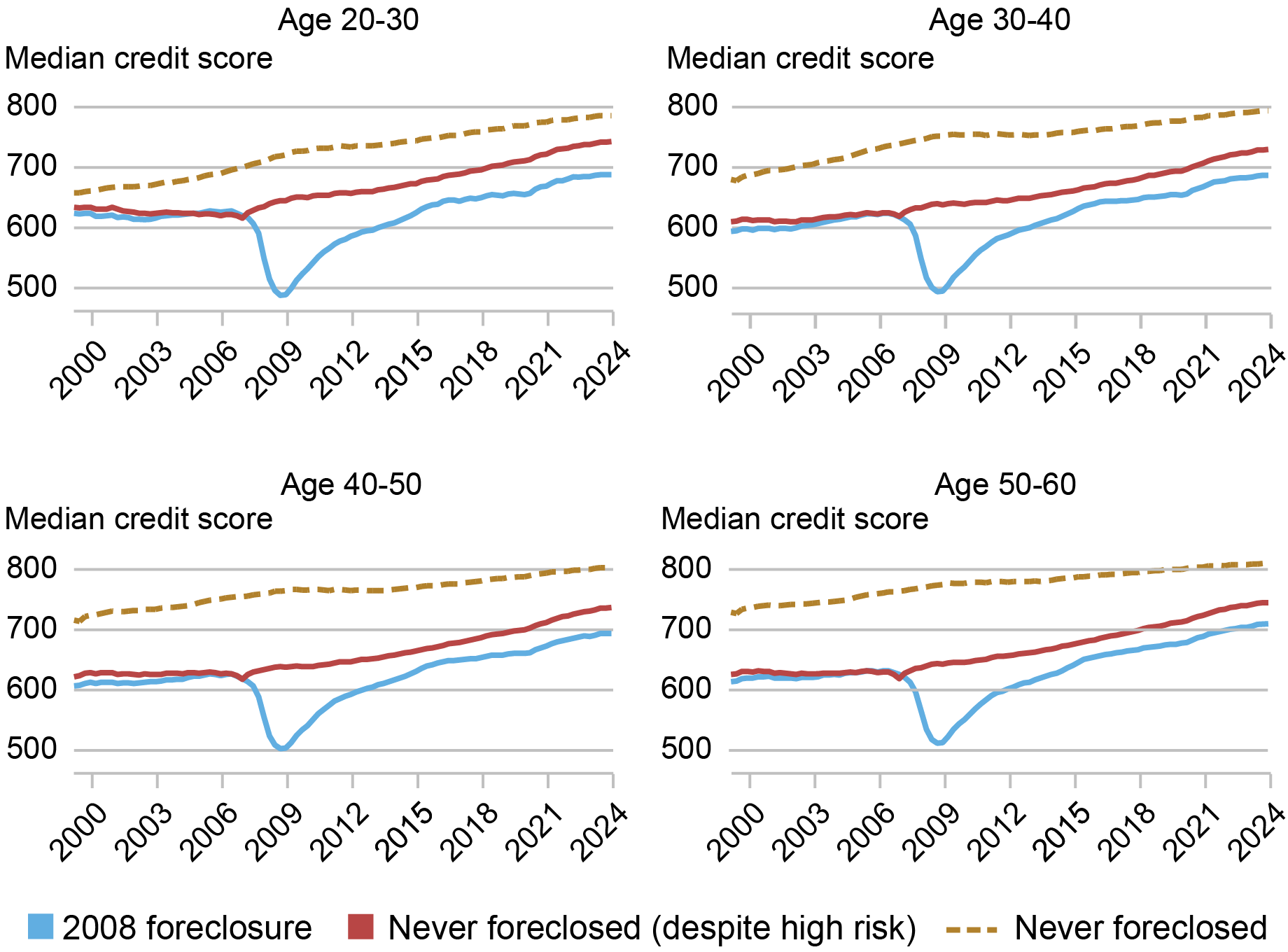

As seen in the charts below, these gaps persist even within age groups, which is somewhat surprising for the younger borrowers who were at the early part of their financial lives.

The Experience of Foreclosure Has a Long-Lasting Impact for Younger and Older Borrowers

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Note: Credit score is Equifax Risk Score 3.0.

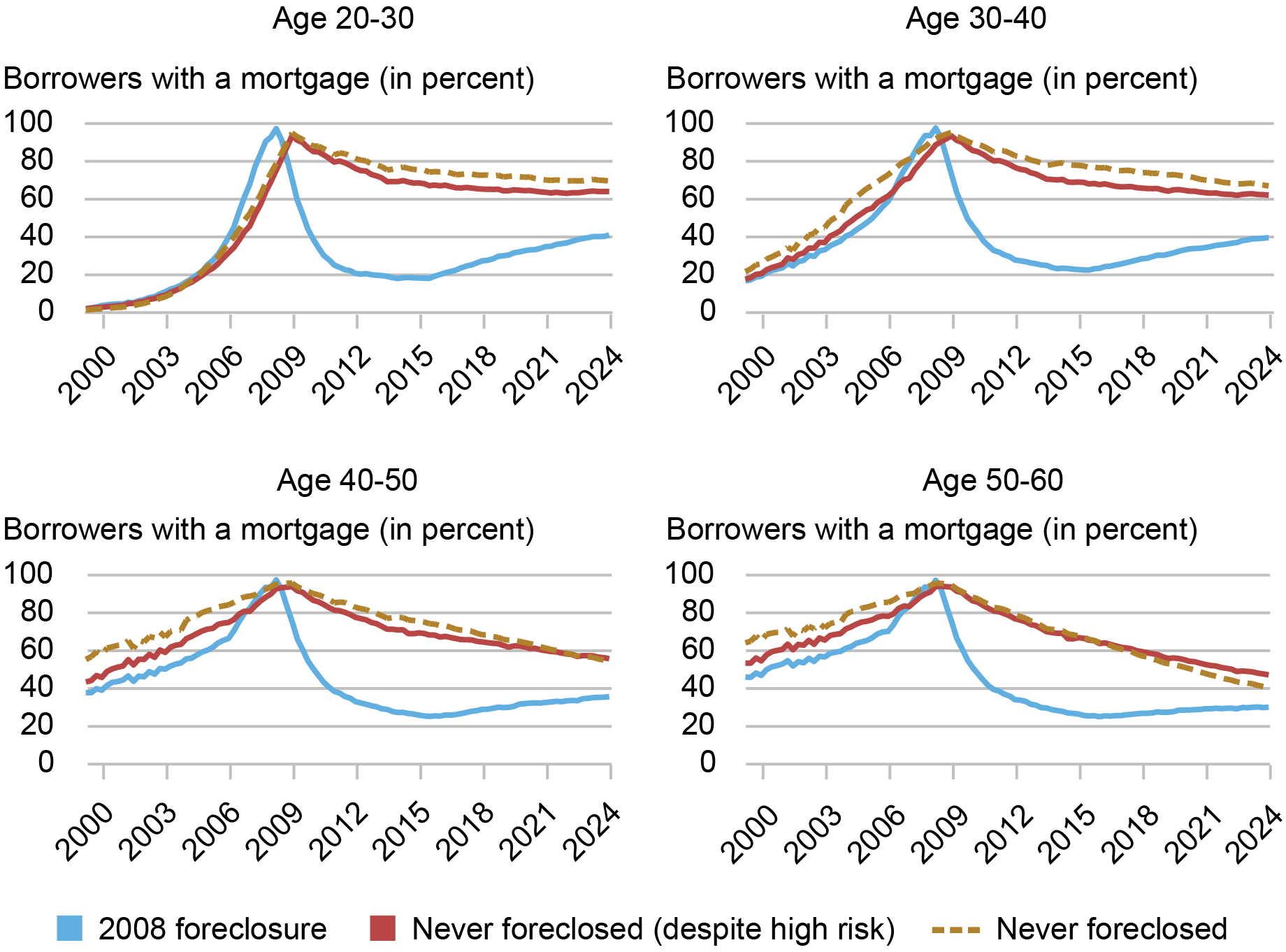

We next consider whether foreclosed borrowers were able to get another mortgage. There is some evidence of financial life cycles driving the return to homeownership, which we define here as the presence of a mortgage on the credit report. For the youngest borrowers—those who were under 30 at their time of foreclosure—a sizeable share has returned to owning a home, although their homeownership rates remain far below those of their peers, as illustrated in the upper panels of the chart below. For older borrowers, the picture is somewhat different: the borrowers who experienced foreclosure see a reduction in homeownership following the foreclosure sequence (but not to zero as many that were foreclosed on had multiple mortgages). However, there is very little pickup in the following years. By contrast, their peers, shown in the dotted gold and red lines in the bottom right panel of chart below, show a gradual reduction in this measure of homeownership, suggesting some combination of a payoff or an exit from homeownership.

Borrowers Who Foreclosed in 2008 Have Significantly Lower Homeownership Rates Now

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Note: Homeownership is defined as having a mortgage on the credit report.

Finally, we consider what types of other debts the borrowers have who foreclosed in 2008 have on their 2023 credit reports. Notably, not all individuals who had a foreclosure were mortgage borrowers; this is because they may have been listed as joint borrowers on the deed but not on the loan, or because the homeowner may have been foreclosed on for reasons other than mortgage nonpayment, such as a lien or tax judgment. We first see, consistent with our findings above, that those who foreclosed in 2008 are far less likely to have a mortgage or a home equity line of credit (HELOC) account compared to the non-foreclosing group. Credit card usage more generally is lower among those who foreclosed. Meanwhile, auto debt is more prevalent among those who foreclosed.

Credit Participation

20082023ForeclosureNo foreclosureForeclosureNo foreclosureHave a mortgage97.6% 100.0% 36.3% 51.1% Have a HELOC17.9%24.5%4.2%12.6% Have an auto loan

55.1% 49.1%46.7%36.6% Have a credit card80.9% 91.9% 73.7%80.7% Median credit score505767696802Source: New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax.

Notes: The “no foreclosure” group includes individuals who never had a foreclosure but did have a mortgage on their credit file in 2008. HELOC is home equity line of credit. Credit score is Equifax Risk Score 3.0.

The foreclosure flags have long disappeared from the credit reports of the nearly 5 million Americans who experienced a foreclosure during the housing bust, yet the financial scarring has lingered on their financial experience in various ways—they have persistently lower credit scores and are less likely to own a home. These consequences are long-term, especially for new entrants to homeownership, resembling in some ways the long-term scarring effects on earnings and employment for young workers who first enter the labor market during recessions.

The economic interventions during the pandemic recession featured unprecedented supports to households and borrowers, reducing (and effectively eliminating) delinquency and preventing foreclosure during the most intense months of economic contraction in 2020. U.S. economic activity and employment rebounded more quickly in this recovery as many Americans were spared the long recovery from a foreclosure event, providing a sharp contrast to the deep marks left on the household sector following the Great Recession. Although the two crises differed in their underlying economic conditions, the prolonged path to recovery from the foreclosure crisis during the Great Recession versus the pandemic bounce-back could be a consideration for policymakers in addressing similar events in the future.

Andrew F. Haughwout is the director of Household and Public Policy Research in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an economic research advisor in Consumer Behavior Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daniel Mangrum is a research economist in Equitable Growth Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Belicia Rodriguez is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Communications and Outreach Group.

Joelle Scally is a regional economic principal in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is the economic research advisor for Household and Public Policy Research in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Daniel Mangrum, Belicia Rodriguez, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw , “How Are They Now? A Checkup on Homeowners Who Experienced Foreclosure,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 8, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/05/how-are-they-now-a....

The New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel: A Foundational CMD Data Set

Do Credit Markets Watch the Waving Flag of Bankruptcy?

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Many Places Still Have Not Recovered from the Pandemic Recession

More than four years have passed since the onset of the pandemic, which resulted in one of the sharpest and deepest economic downturns in U.S. history. While the nation as a whole has recovered the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, many places have not. Indeed, job shortfalls remain in more than a quarter of the country’s metro areas, including many in the New York-Northern New Jersey region. In fact, while employment is well above pre-pandemic levels in Northern New Jersey, jobs have only recently recovered in and around New York City, and most of upstate New York—like much of the Rust Belt—still has not fully recovered and has some of the largest job shortfalls in the country.

In this post, we examine the uneven geographic recovery from the pandemic recession, including why some places are finding it so difficult to recover. Many of the places that have not regained the jobs lost were hit particularly hard by the pandemic, leaving a deeper hole to dig out of. Further, these places tended to be slow-growing local economies leading up to the pandemic, leaving less momentum for a full recovery, and they face ongoing struggles finding the workers they need to grow. Indeed, with such persistent headwinds, many of these places are likely to continue to struggle to fully recover from the pandemic recession.

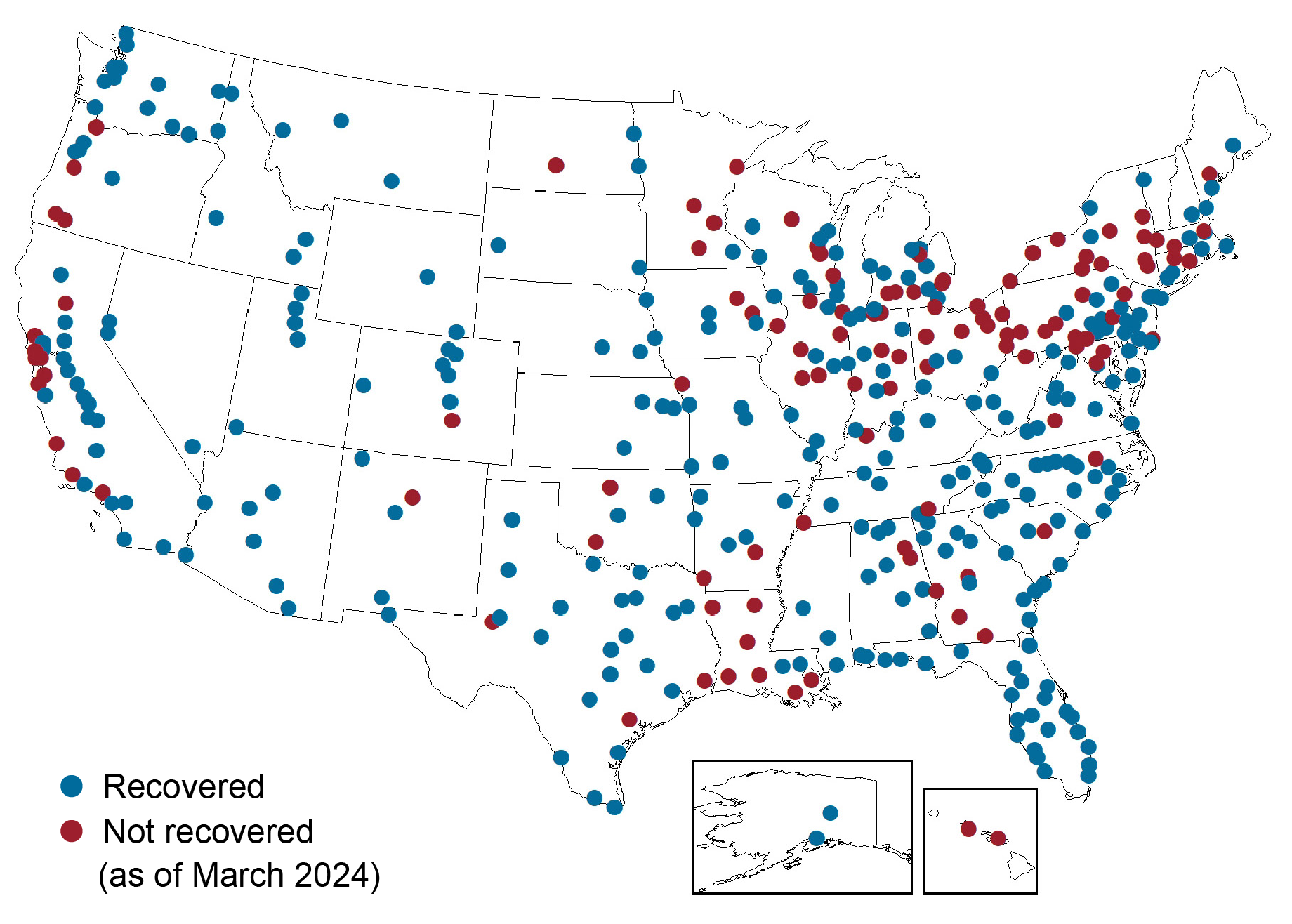

Most Places Have More Than Fully Recovered, But Many Have Not

Employment fell nearly 15 percent in the United States between February 2020 and April 2020—a shockingly large decline in such a short period of time. The country had dug itself out of this massive hole by the summer of 2022, recovering all of the jobs that were lost, and employment is now nearly 4 percent above pre-pandemic levels. As the map below shows, however, the recovery has been uneven and remains incomplete in many places. Indeed, while most metro areas have recouped the jobs that were lost during the recession (shown as blue dots), more than 25 percent still have not (shown as red dots). Most of these areas are concentrated in the Rust Belt along the Great Lakes, though clusters are present in parts of the South—Louisiana in particular—as well as in California, Oregon, and Hawaii. In fact, employment is still more than 5 percent below pre-pandemic levels in New Orleans, and more than 3 percent below in Honolulu and San Francisco. Likewise, sizable job shortfalls remain in Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. At the other end of the spectrum, employment in fast-growing parts of the country such as Austin, Boise, Phoenix, Raleigh, Charleston, and Sarasota is now more than 10 percent above pre-pandemic levels. (Download the full set of metro-area data and rankings).

An Uneven Geographic Recovery from the Pandemic Recession

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

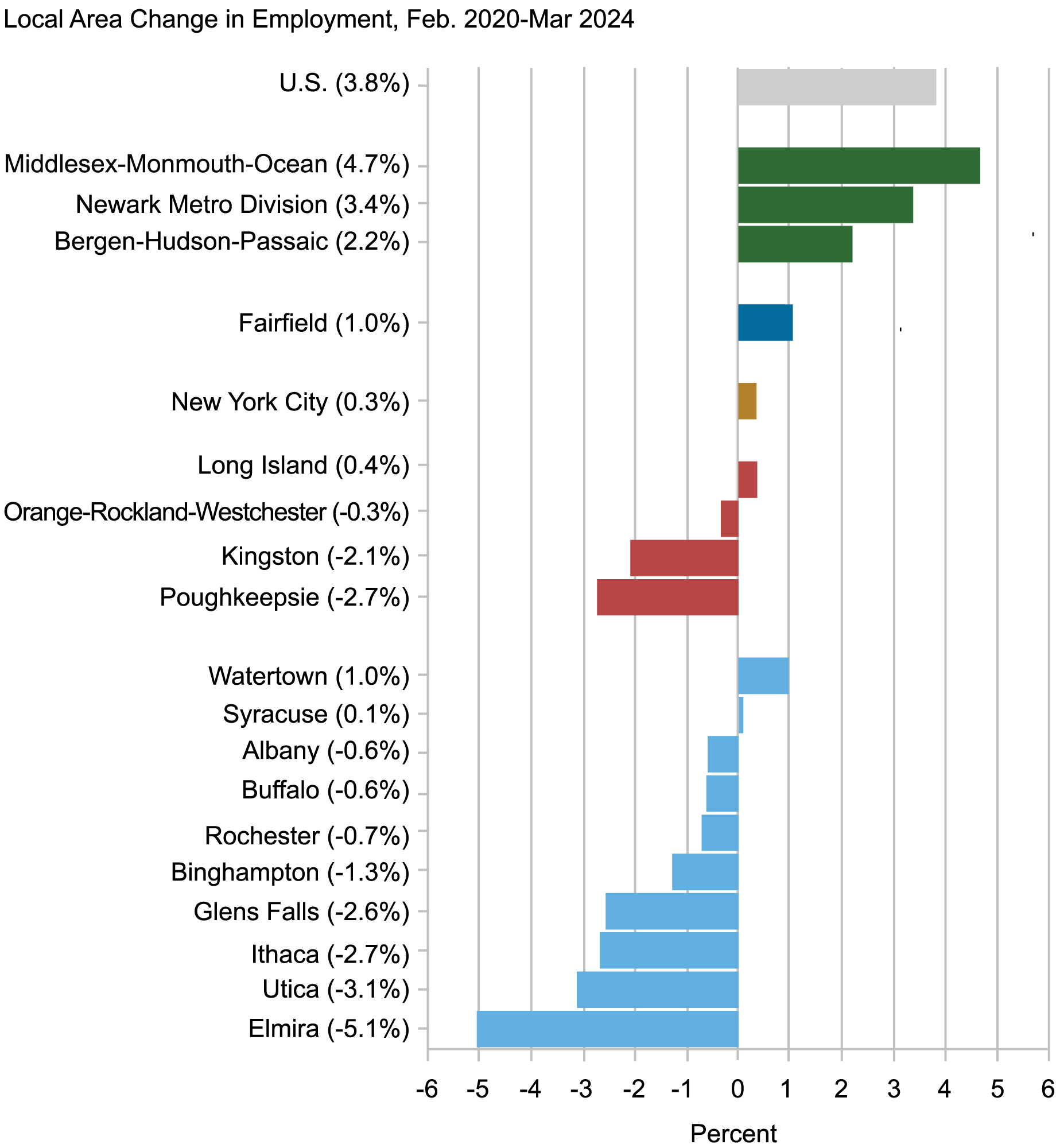

Much of The New York-Northern New Jersey Region Is Still Way Behind

The New York-Northern New Jersey region was hit especially hard by the pandemic, and has been slow to recover. The chart below shows the change in employment from February 2020 to March 2024 for local areas in the region compared to the nation as a whole.

Large Job Shortfalls Remain in Much of the N.Y.-Northern N.J. Region

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

Employment is well above pre-pandemic levels in Northern New Jersey, though generally to a lesser extent than nationally, and is firmly above pre-pandemic levels in Fairfield, Conn. Though it took one-and-a-half years longer than for the nation as a whole, New York City has now recovered the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, but only just so, leaving it well behind the nation. Notably, the jobs gained in New York City during the recovery have not been the same as the jobs that were lost. Indeed, much of the City’s job growth has been in the healthcare sector, which is up almost 14 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels. And while there has been growth in high-paying sectors such as finance and business services during the recovery, lower-paying sectors such as retail, leisure & hospitality, and personal services that depend on foot traffic from office workers and visitors continue to lag.

While Long Island has just recently fully recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels, job shortfalls remain in much of the rest of New York State, including Kingston and Poughkeepsie as well as nearly every metro area in upstate New York, where some of the largest job shortfalls in the country remain. Indeed, Elmira’s employment level is still 5 percent below its pre-pandemic benchmark, ranking as the eighth-largest job deficit of all metro areas in the country. Utica, Glens Falls, Ithaca, and Poughkeepsie all have job deficits ranging between 2.6 and 3.1 percent, ranking among the twenty-five largest shortfalls in the nation. Focusing on upstate New York’s largest metros, Syracuse has now only just recovered the jobs that were lost, and Albany, Buffalo, and Rochester all have job deficits around 0.6 to 0.7 percent.

Why Are Some Places Finding It So Hard to Recover?

The metro areas that are lagging in the jobs recovery share some common features. First, many of them were hit particularly hard during the initial shock, leaving a bigger hole to dig out of. On average, the places that have not yet recovered experienced an employment decline of 16.1 percent during the pandemic recession compared to a 13.4 percent decline in the places that have recovered. While industry composition certainly played a role in the depth of the decline—in particular, local economies reliant on tourism suffered large losses—declines were quite steep in places where the pandemic first took hold. Specifically, clusters of job deficits persist in New York, California, and Michigan, all of which emerged as coronavirus hot spots and had outsized job declines early in the pandemic. Indeed, initial job losses in the New York-Northern New Jersey region averaged almost 19 percent, and parts of California and Michigan saw initial job losses well above 20 percent.

In addition, many of the places that have not recovered were slow-growth economies heading into the pandemic, leaving less momentum to grow and recover coming out of it. Indeed, the metro areas with job deficits saw average annual job growth of just 0.5 percent in the five years leading up to the pandemic, compared to 1.5 percent, on average, for those that have recovered. Over the past year, slower job growth in the areas that have not yet recovered has resumed.

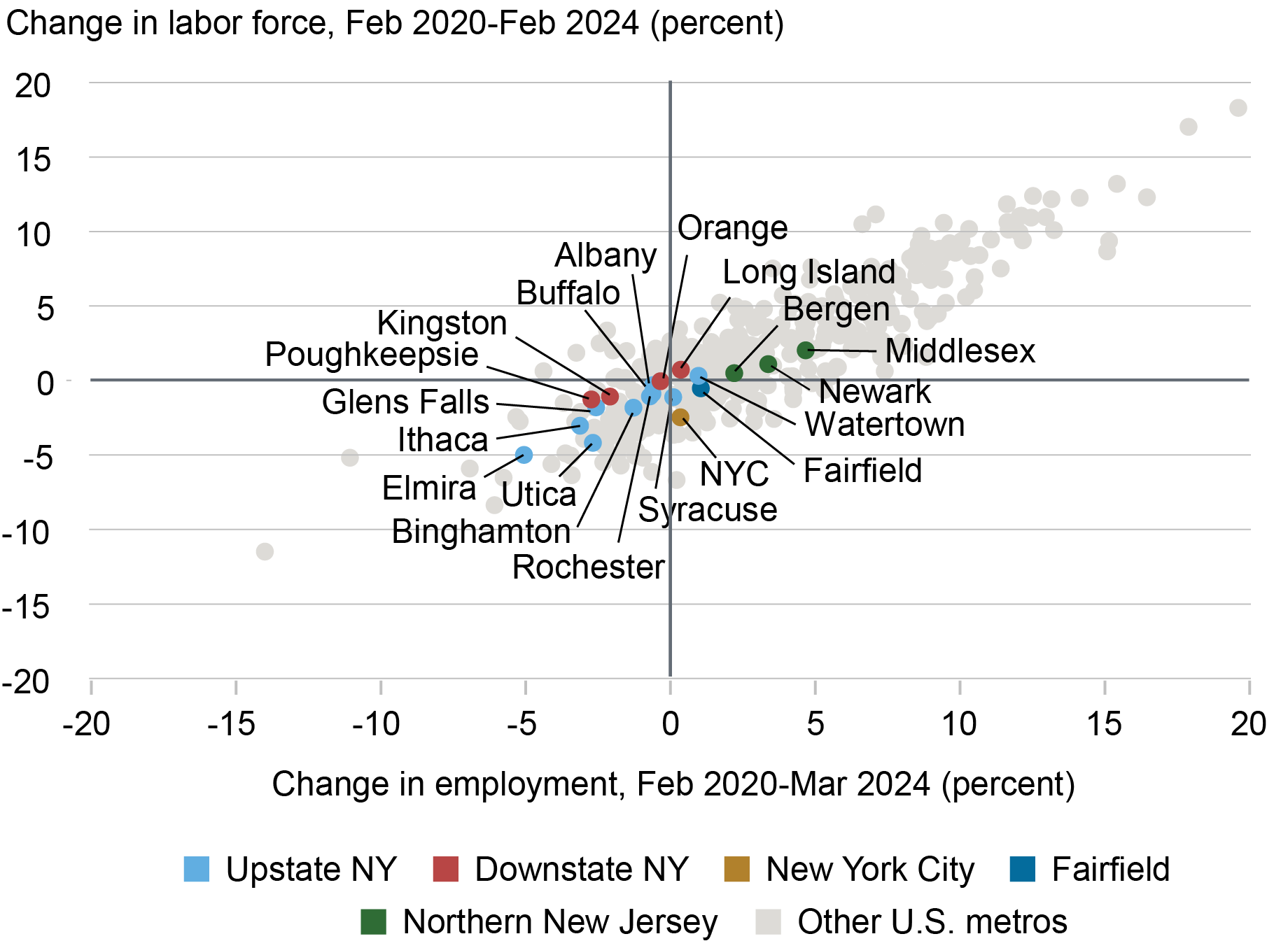

Further, many places that have not recovered just don’t have the workers to allow their local economies to grow. With persistent worker shortages across the country since the pandemic, labor has often been hard to find, and that’s been especially true in places that still have job deficits, as shown in the chart below. Here we plot pre-pandemic job gains/deficits for local areas against the change in that area’s labor force since the pandemic hit. While remote work has decoupled where people live and work to some extent, the vast majority of workers still live in commuting distance to their employers. Indeed, the clear upward-sloping pattern shows the close connection between job growth and the availability of workers both across the country and within the region.

Worker Availability Contributing to Persistent Job Shortfalls

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Moody’s Economy.com.

Local areas shown in the upper right quadrant, including those in Northern New Jersey, have seen growth in their local labor forces, and employers are more able to find the workers they need. As a result, such places are seeing employment climb well above pre-pandemic levels. At the other end of the spectrum, areas in the lower left quadrant have seen their labor forces shrink and have job deficits. Parts of upstate New York such as Binghamton, Elmira, and Utica saw labor force declines, which were in fact already occurring before the pandemic hit, in part due to population aging and people leaving the area. Clearly, more people willing and able to work will be required to achieve a full recovery in this part of the region, but with ongoing long-term labor force decline, these places and others like them are likely to continue to struggle to gain back the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession. New York City has been able to gain back the jobs that were lost despite a declining local labor force, largely because it can draw workers from a broader surrounding geographic area.

The New Normal Is the Old Normal

Four years after the pandemic hit, historical growth patterns have generally resumed throughout the country after a period of rapid recovery. The places that were growing more strongly before the pandemic have generally recovered and are growing more strongly today, while many places that lagged are still struggling to recover. Indeed, more than a quarter of the country has not gained back the jobs that were lost during the pandemic recession, including most of upstate New York. Some places in upstate New York were hit by a “triple whammy” of slow growth leading up to the pandemic that has now resumed, a deeper hole when the pandemic hit, and a declining labor force. As such, upstate New York, and many places like it, may well continue to struggle to reach employment levels seen before the pandemic.

Jaison R. Abel is the head of Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an economic research advisor in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jonathan Hastings is a research associate in Urban and Regional Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a regional economic principal in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel, Richard Deitz, Jonathan Hastings, and Joelle Scally, “Many Places Still Have Not Recovered from the Pandemic Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/05/many-places-still-....

The Tri‑State Region’s Recovery from the Pandemic Recession Three Years On

New York Fed Surveys: Business Activity in the Region Sees Historic Plunge in April

The Region Is Struggling to Recover from the Pandemic Recession

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West – review

In As Gods Among Men, Guido Alfani examines the history of the rich in the West from the Middle Ages to modern times, including paths to wealth, societal perceptions and their resilience against shocks. Contributing to a recent surge in research studying inequalities, Alfani provides a nuanced economic history that probes conventional understandings of how great wealth has been accumulated, writes Noah Sutter.

With As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West, Guido Alfani presents a comprehensive history of the wealthy in the West from the Middle Ages until today. The book provides a rich and vivid account of the history of the affluent and their interplay with society across centuries.

With As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West, Guido Alfani presents a comprehensive history of the wealthy in the West from the Middle Ages until today. The book provides a rich and vivid account of the history of the affluent and their interplay with society across centuries.

It consists of three parts. The first part introduces concepts and definitions to delineate the group of people who are the main focus of the study. The second part outlines the main paths to affluence and how they changed over the course of history, including the nobility, entrepreneurship and finance. It closes with a discussion of the saving and consumption habits of the rich, as well as a final chapter which discusses how phases with a wealthy elite relatively open to newcomers give way to phases of an ossified social hierarchy. The final part is dedicated to the role of the rich within society.

The rich in their changing guises have been a major historic force for centuries. Consequently, their historic traces can be found everywhere and form a rhizomatic network across time and space in the history of the West.

Rather than featuring a single argument or thesis, the book is a collection of ideas and different theses. It raises many questions while answering even more. Several threads are followed throughout the book. The rich in their changing guises have been a major historic force for centuries. Consequently, their historic traces can be found everywhere and form a rhizomatic network across time and space in the history of the West. Alfani masterfully isolates several key threads from this network.

The unifying thread Alfani identifies throughout history is that Western societies have struggled to find an appropriate role for the rich, and continue to do so. He describes in detail both the theological discussions that lay at the heart of the Western mind’s uneasiness with the wealthy and the useful social roles that the rich did fulfil. These did include magnificence – making their city splendid through their generosity – and their role as living “barns of money” – resource pools to tap into in times of crisis. The third part also contains a discussion of the role of the rich in politics, as well as discussions of the effects of crises – epidemics, wars, and financial – on the wealthy.

It seems that the rich only suffer economic decline if they are hit by catastrophe unawares.

The conclusions which Alfani reaches are often surprising. It seems that the rich only suffer economic decline if they are hit by catastrophe unawares. This was the case with the Black Death, the Thirty Years War and the World Wars. These shocks lead to adaptations and innovation that make the rich more resilient to future shocks.

One of his main conclusions, that the position of the rich in society is intrinsically fragile is rather counterintuitive – especially to the student of social mobility. Studies in economic history have shown that the top end of distribution of wealth and status distribution seems to be much more persistent than previously assumed, pointing towards a rigid social order. Alfani does not deny this but points to the aforementioned episodes of history and hints at the contemporary wealthy’s awareness of that fragility.

The second part especially – dedicated to the paths to affluence – is full of interesting observations and conclusions offering potential strands of further research. Among these is his discussion of the determinants of the openness of wealthy elites across time. Alfani discusses episodes like the opening of Atlantic trade routes, colonisation, and the Second Industrial Revolution which widened access to the elite of the rich to “new men”.

The book is the latest major contribution to a still-growing literature on economic inequality around the distribution of wealth. Branko Milanović’s most recent book, Visions of Inequality, describes how the 20th century was a period of “eclipse” in the history of economic inequality studies. One of the reasons for the eclipse that Milanović describes is that during the Cold War, both sides of the conflict tried to downplay class divisions within the respective societies. Another reason Alfani identifies is the difficulty of conceptualising the rich for economic theory. Under the assumptions of the widespread permanent income (Friedman) or life-cycle (Modigliani) hypotheses, where individuals ideally consume all their income before their death, the emergence of wealthy dynasties is hard to fathom. This eclipse ended with both the Great Recession starting in 2008 and the publication of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. Economic inequality had (again) become one of the central topics of economic research. This recent trend towards the study of economic inequality has shifted the focus from income to wealth. This in turn led to a less optimistic view of the possibilities of creating a more level playing field through economic growth since wealth is much more persistent across generations than income.

The most interesting idealist thread that runs through the book is the influence of Christian theology on how we think about the role of the rich in society.

The book is part of a recent wave of books that complement the previous focus on the empirical description of trends in the development of inequality with richer narratives that combine the history of ideas with economic history, including the above books by Milanović and Piketty. Especially noteworthy were Milanović’s previously mentioned Visions of Inequality and Piketty’s Capital and Ideology. While the former provides a materialistic account of the history of inequality studies, the latter provides an idealistic account of how ideas and ideologies stabilised different inequality regimes. As Gods Among Men neglects neither channel. The most interesting idealist thread that runs through the book is the influence of Christian theology on how we think about the role of the rich in society. This is already apparent in the title, a quote from Nicole Oresme – medieval political thinker, scientist and bishop. Christian theology, with its distrust of the wealthy (“Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”, Matthew 19:24!), its classification of not only avarice and greed but also vain, glory and gluttony as deadly sins, as well as its prohibitions on usury, was – and arguably remains – a main contributor to the unease towards the wealthy in the West. The discussion on “useful roles” bears resemblance to Piketty’s discussion of legitimising ideologies. While Piketty provides a critique of ideology, Alfani invites us to think about how we should deal with the presence of the very rich in our societies. What does it mean that in recent cases as opposed to historical ones the rich have not been asked to foot the bill?

If we see the laws of production as ‘physical’ or ‘mechanical’ and thereby apolitical, no distribution of wealth is inherently just or unjust.

Tremendous progress has been made since the publication of Piketty’s seminal book in terms of understanding historical inequality. The political effects of these debates have been negligible, however. It is possible that the wave of research on inequality has remained politically rather sterile because our thinking on inequality had been one-dimensional for some time. We may need new ways of thinking about inequality of distribution. If we see the laws of production as “physical” or “mechanical” and thereby apolitical, no distribution of wealth is inherently just or unjust. Only through deepening our understanding of the processes and the political economy which bring about the stratum of the wealthy, and thereby the distribution of wealth, can we determine what levels of inequality can be justified and how to achieve them. Alfani uses the image of the rich as the pearl brought forth by society – the oyster. This process of pearl formation must be studied. Maybe we must turn Marx’ dictum from the Theses on Feuerbach back on its head and say that in order to change the world, we first have to interpret the world in new ways. Alfani provides us with another important step in this direction. It is long overdue that his work is introduced to the wider public.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: PeopleImages.com – Yuri A on Shutterstock.

On the possibility of a recession at the Rick Smith Show

My brief interview at the Rick Smith Show on the likelihood of a recession this year, and the unfounded fears about public debt in the United States.

Vibecession over

Though I’m certainly not the first to make this observation, it looks like the “vibecession” is over. The term was coined in June 2022 by multimedia economic analyst Kyla Scanlon (drawing on Keynes but also the poetry of Charles Bukowski), who defined it as “a disconnect between consumer sentiment and economic data. So basically, the economy is doing fine, but people are absolutely not feeling fine.” By recent measures, people are starting to feel somewhat finer, if not bounce-off-the-walls fine.

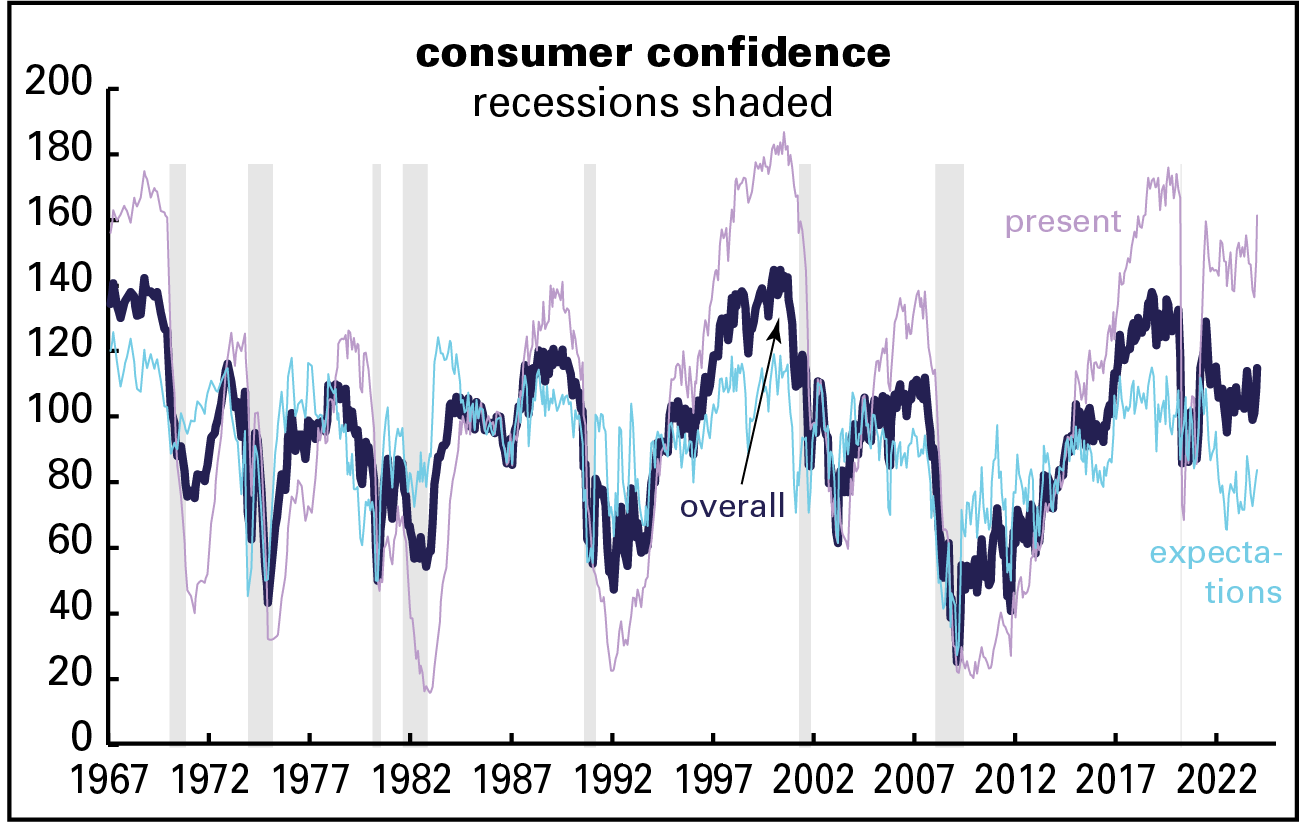

The Conference Board’s consumer confidence index rose 6.8 points in January to its highest level since December 2021. The index is the summary of a monthly survey the organization has conducted since 1967 that asks people questions about the state of the economy, the job market, and their personal finances, both in the present and their expectations for the future. Separate indexes for the present and expectations questions are computed, and then averaged into a composite. The history is graphed below.

January’s rise in the composite was led by its “present conditions” component, up 14.1 points to the highest level since March 2020. Driving the rise were improving evaluations of the job market, as the gap between those reporting “job plentiful” and those reporting them “hard to get” expanded 8.4 points to 35.7 in favor of plentiful—very high by historical standards (higher than 94% of all the months in its 57-year history). Expectations, alas, are more muted.

Gallup agrees on the improvement, though not on its degree. The present component of their economic confidence index rose to its highest level since November 2021 in January, but it’s still negative on balance. (It’s computed as the difference between the share of respondents calling the economy excellent or good and the share calling it poor. Just 5% of respondents in the January survey called it “excellent,” and 22% “good.” Far more, 45%, called it poor. for a net of -18%.) The expectations side, while also net negative, is at its least negative level since September 2021. There’s no graph of these because there are often long stretches between surveys and such a graph would be ugly.

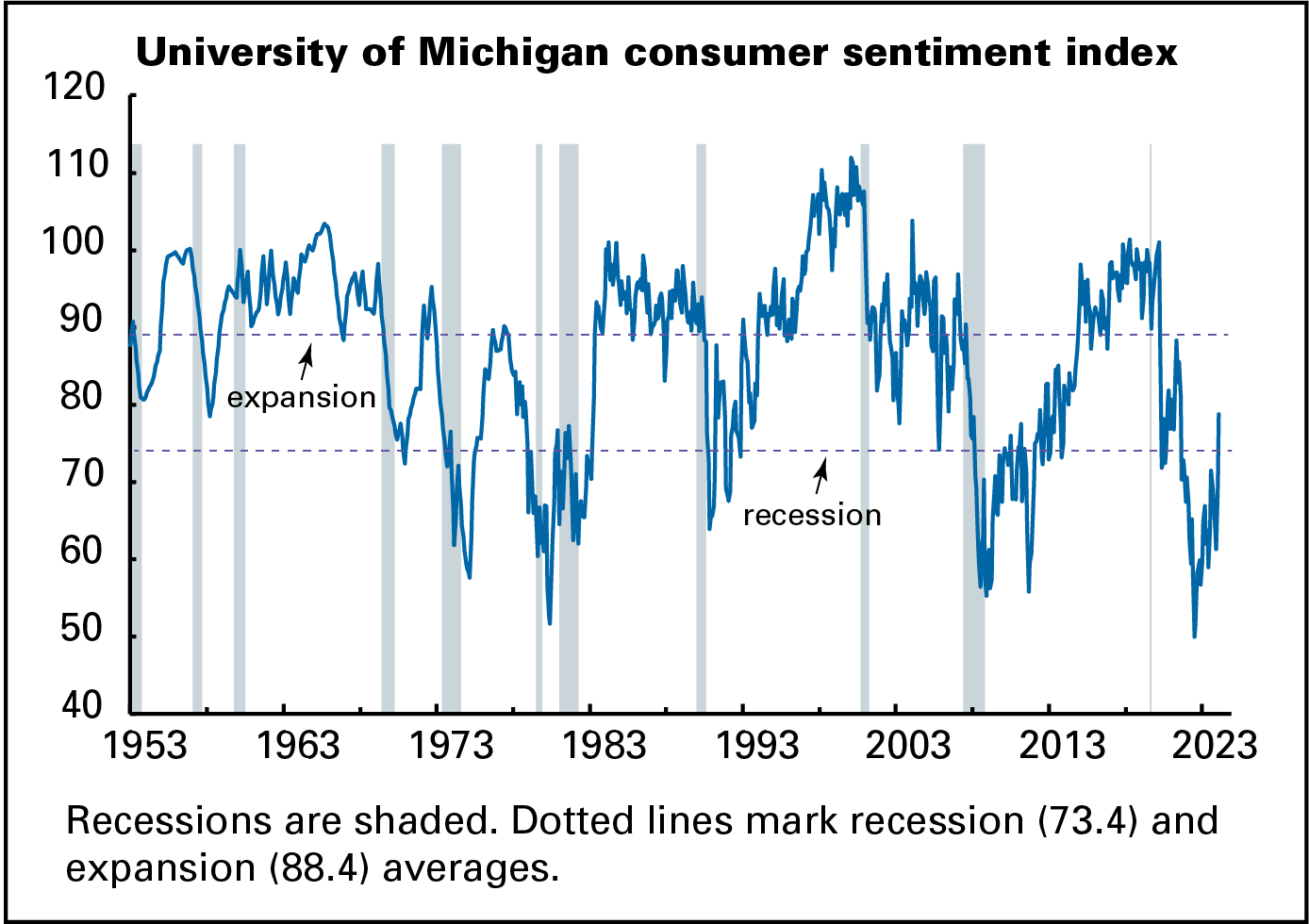

And another: the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment measure (graph below) was up 9.1 from December on its preliminary January reading, reaching its highest level since July 2021. It was also led by evaluations of the present, though expectations were somewhat loftier than the Conference Board’s counterpart. Sentiment had really been plumbing the depths: in June 2022, the month Scanlon coined the term, the index hit 50.0, its all-time low in over seven decades of history—below the depths of the Great Recession. Not coincidentally, it was also the month of peak inflation.* The sentiment index’s full-year 2023 average was 8 points below the long-term recession average. January’s improved reading was nonetheless still almost 10 points below the average of all business cycle expansions since 1952.

inflation down

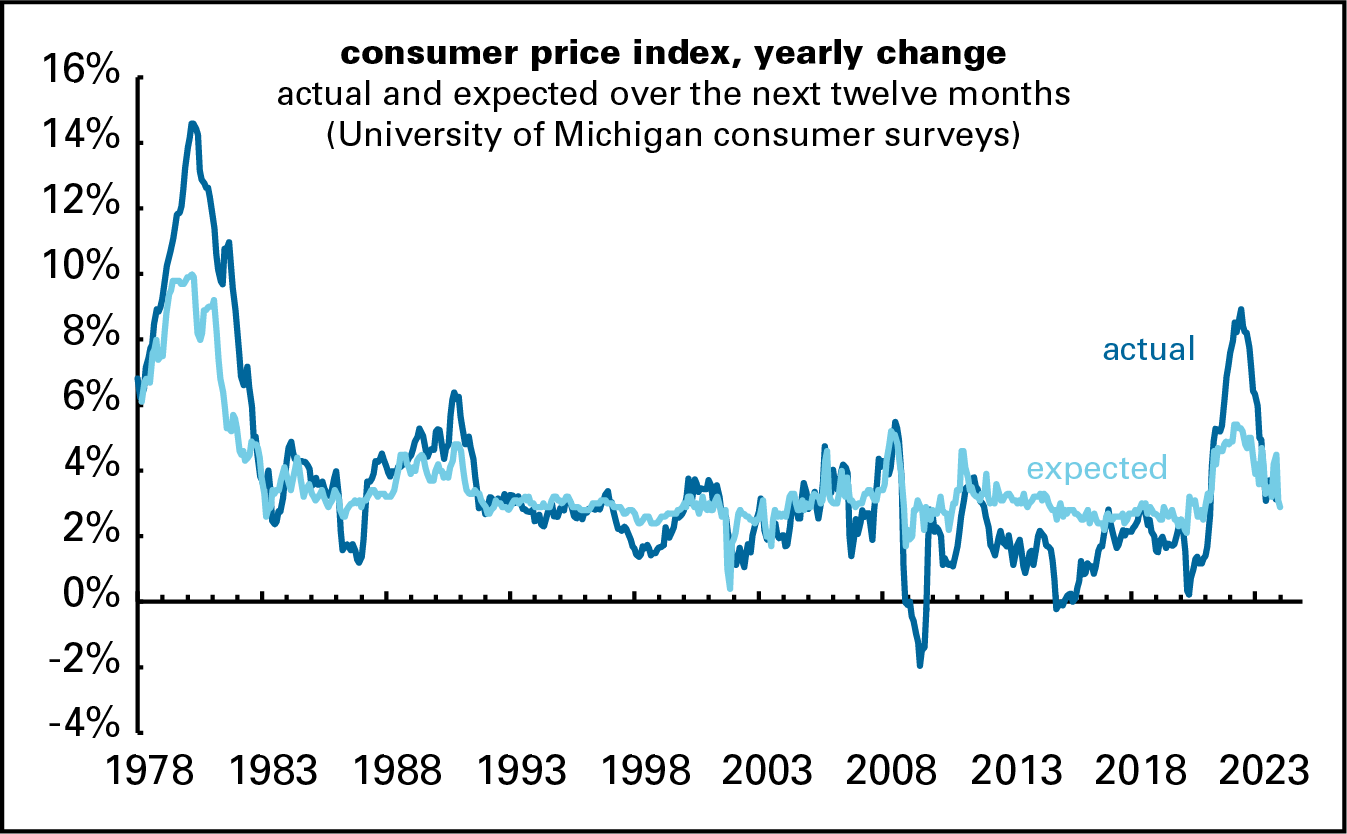

Much of this improvement in outlook is the result of the decline in inflation, from 8.9% in June 2022 to 3.3% in December 2023, a fall of almost two-thirds. We hadn’t seen 8.9% in 42 years. December’s 3.3% is above the 1990–2019 average of 2.5%, but not profoundly so.

Along with the decline in actual inflation has come a decline in expected inflation. I’ve long thought that instruments that measure “expectations” are mostly about the present and recent past and have little or no prognostic content. (As the graph below shows, expectations for price increases over the next twelve months generally track the experience of the previous twelve.) Instead, expectations can be read as a measure of a subjective state—in this case, how established inflation feels as a part of life, what the current norm is.

By this measure, inflation’s psychological grasp looks to be slipping. As the graph shows, expectations for the next year have come down along with actual inflation, from over 5% in mid-2022 to 2.9% in January.

That matters a lot—people hate inflation! Liberals and leftists tend to dismiss inflation as a concern of anal-retentive reactionaries, but that badly misreads popular opinion. I made this argument at some length in my long Jacobin article on inflation, but here’s another piece of evidence to add to that: Scanlon cites a Morning Consult poll that found 63% of consumers prefer prices going down to their income going up. Economists natter on about “real” (inflation-adjusted) income, but they may not be giving enough weight to the price part.

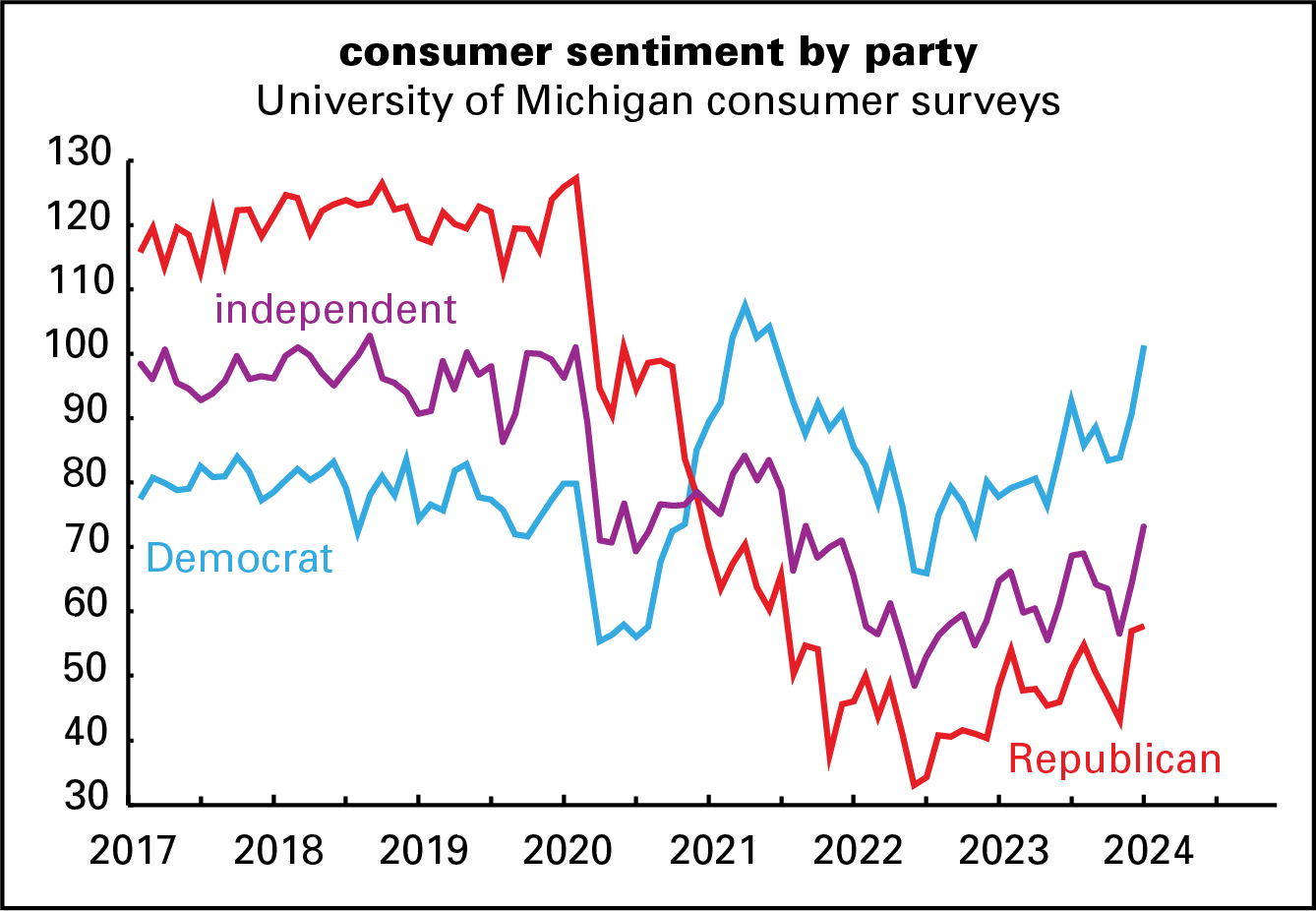

partisan coda

Speaking of the Michigan sentiment numbers, the improvement in outlook over the last couple of months crosses partisan lines, but the gap between Democrats and Republicans widened. Partisan gaps have long been visible in the survey, but they were much less dramatic than they’ve been since January 21, 2017. During the Obama years, Dems’ consumer sentiment ratings were about 18 points higher than Republicans’. During the Trump years, the gap more than doubled to 39 points, though it switched parties to favor Republicans. For first three of the Biden years, the parties flipped again, as Dems’ evaluations exceeded Reps’ by 35 points, even though nothing had changed by conventional economic measures. Independents, not surprisingly, split these differences.

Between November 2023 and January 2024, both parties saw strong increases in their evaluations of the economy, but Dems, up 17 points, were more enthusiastic than Reps, up just 15. So the gap widened to 44 points.

Much of the lift to the overall sentiment measure for Republicans—over three-quarters of it—came from expectations, not evaluations of the present; perhaps they’re hopeful about November’s election results.

Otherwise, the end of the vibecession might be good news for the hapless warmonger Biden, who needs some.

* In June 2022, when the sentiment measure was at its record low of 50.0, the unemployment rate was 3.6%. It was also the high for the recent inflation surge: 8.6%. In October 2009, when the unemployment rate was 10.0%, the worst reading of the Great Recession, the sentiment index was 70.6. But there was literally no inflation: for the year ending October 2009, the consumer price index was down 0.2%.

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises that Shaped Globalization – review

In Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises that Shaped Globalization, Harold James explores major market crashes from the last 170 years, examining their causes (whether they were demand or supply crashes) and their impacts on globalisation. In Kyle Scott‘s view, the book shares valuable, engaging analysis of these economic crises, though its apparent aim to appeal to both general and specialist audiences falls somewhat short.

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises that Shaped Globalization. Harold James. Yale University Press. 2023.

In the wake of the predicted financial crash of 2022 that never was, commentators are scratching their heads as to why it hasn’t happened. There has been inflation, rising interest rates and job loss, but economies have continued to grow and recession in most countries has been averted. It seems economists, and economic prognosticators, are not great at predicting events. Following the 2008 market crash, there were a few people positioned to profit from the collapse, but that there were not more economists shorting the housing market and financial institutions seems to be good evidence of their limited forecasting capabilities.

In the wake of the predicted financial crash of 2022 that never was, commentators are scratching their heads as to why it hasn’t happened. There has been inflation, rising interest rates and job loss, but economies have continued to grow and recession in most countries has been averted. It seems economists, and economic prognosticators, are not great at predicting events. Following the 2008 market crash, there were a few people positioned to profit from the collapse, but that there were not more economists shorting the housing market and financial institutions seems to be good evidence of their limited forecasting capabilities.

But economists can look back and teach us what lessons we should have learned. In Seven Crashes: The Seven Crises that Shaped Globalization, Harold James looks at seven market crashes and tries to draw a few important lessons for readers. How successful this historical look will be at informing our understanding of the future is unknown.

James divides crashes into “good” and “bad, defining as good those that lead to increased globalisation and prosperity and bad those that lead to markets contracting or turning inward.

James, the Claude and Lore Kelly Professor of European Studies at Princeton University, has spent a career studying economic history. He is a prolific author who is also the official historian of the International Monetary Fund. James divides crashes into “good” and “bad”, defining as good those that lead to increased globalisation and prosperity and bad those that lead to markets contracting or turning inward.

In reading his accounts of each of these crashes, there were events that occurred in foreign markets that led to crashes in domestic markets. There were also close linkages between private financiers and governments that eventually soured when the financier’s business interests unravelled and caused harm to the government’s finances and citizens.

For instance, Ivar Kreuger, an account of whom is provided in chapter four, founded the Swedish Match Company in 1907. In his attempt to gain a worldwide monopoly on matches, he would lend money to governments in exchange for his company to have exclusive access to their markets. Kreuger raised capital in the US to buy undervalued assets in Central Europe to expand his match manufacturing and distribution empire during the mid-1920s. He lent money to France, Greece, Ecuador, Latvia, Estonia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Bolivia, Guatemala, Poland, Turkey, and Romania. In order to expand this scheme to Germany, and gain control of the German match market, he raised capital in the US through complex debt instruments. His timing could not have been worse, as the scheme was executed in October of 1929. The Kreuger empire crumbled – in part because of the market crash and in part because of his fraudulent accounting practices – and the effects reverberated in countries that relied on his money and his counsel.

In James’s telling, the Great Depression led to deglobalisation even after World War Two

In James’s telling, the Great Depression led to deglobalisation even after World War Two for several reasons. First, technology, particularly in America, increased production in a way that made international trade less important than domestic consumption. Second, World War Two ignited the domestic production engine of many countries as global trade was limited during the war while demand was high. Third, governments enacted protectionists policies such as tariffs that made foreign goods less competitive and emigration restrictions that insulated domestic workers from competition which drove up wages.

As a result [of the economic crash in the 1840s] business leaders and governments recognised that globalisation was necessary to build interconnected economies resistant to resist supply shocks.

The Great Depression was caused by a demand shock, whereas the crash in the 1840s was precipitated by a supply shock. In Chapter One, James demonstrates that the crash of the 1840s in Europe was caused by “famine, malnutrition, disease, and revolt” (26). As a result, business leaders and governments recognised that globalisation was necessary to build interconnected economies resistant to resist supply shocks. Central banks and financiers gained more influence during this period as new sources of capital were needed to finance new projects. Governments incentivised domestic production as well as trade with foreign markets. The eventual effect of this interconnectedness was a deflationary effect on prices coupled with new financial instruments developed to finance large infrastructure projects like railroads. The new financial schemes enabled greater accumulation of capital by financiers and titans of industry. Exuberance preceded – as it had in the 1920s – the crash of the 1870s. The accumulation of capital and globalisation meant the crash was widespread. This begs a question that James does not answer. Why is globalisation good if it can result in contagion which makes the effects of crashes deeper and more widespread? It would be helpful for the reader to understand how James would address this.

Why is globalisation good if it can result in contagion which makes the effects of crashes deeper and more widespread?

The book seems to be written for two audiences, which might leave both unsatisfied. It appears to be written for a general audience, but the anecdotes seem to be drawn haphazardly and there is not an obvious outline that would make it easy for the general reader to draw parallels between chapters. The chapter titles themselves do not offer much help in terms of a timeline, as the names are only useful for those already familiar with economic history and the phrases used to describe the various crashes. For instance, chapter 2 is titled “Krach at the Margins.” Most readers will not know he’s referencing when “krach” was first used to describe a financial crisis in 1873. The introduction lacks a list of the seven crashes that the book is about to tackle. An academic audience, who will be more comfortable with some of the references, will be underwhelmed by the rigor of the research. What general readers will enjoy, however, are the biographies of influential economists during each of the crashes and how their views were either reflective of, or influenced, the decisions of policy makers and business leaders. James acknowledges that their effect is limited, but it opens a set of interesting questions about where economic ideas come from and how they disseminate. His treatment of economists such as Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, and Friedrich Hayek is interesting and illuminating.

[The book] sheds light on our most recent period of economic uncertainty and provides an interesting view of crashes by defining them as either demand crashes or supply crashes.

Those qualms aside, this book is an easy and informative read. It sheds light on our most recent period of economic uncertainty and provides an interesting view of crashes by defining them as either demand crashes or supply crashes. Readers who want to know more about the differences and similarities between crashes, the ramifications of each, and what effect the COVID-19 lockdowns had on international economic development will enjoy this book. Adding prominent economic thinkers into the mix provides a refreshing reprieve from the recounting of events. James does a great job showing the extent and limitations of economists on the thinking of the time. The biographical accounts of economists, and their role in practical affairs, is a unique feature of this book that distinguishes it from other books in the field which makes it well worth the read. This alone makes the book worth a read even if one does walk away paraphrasing Anna Karenina: “Prosperous times are all alike; every market crash happens for its own reasons.”

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Everett Collection on Shutterstock.

Canada: Ten things to know about the federal role in housing policy

I’ve written a 750-word overview of the federal role in housing policy.

The English-language version is here: https://nickfalvo.ca/canada-ten-things-to-know-about-the-federal-role-in-housing-policy/

The French-language version is here: https://nickfalvo.ca/canada-dix-faits-saillants-sur-le-role-du-federal-en-matiere-de-politique-du-logement/

the recession’s likely long-term impact on homelessness

I’ve just written a report for Employment and Social Development Canada on the current recession’s likely long-term impact on homelessness in Canada. An overview of the report can be found here.