drought

This Utah County Will Buy Your Lawn to Save Water

The Virgin River cuts through a towering red rock gorge flanked by forested plateaus as it meanders through Washington County in southern Utah. The river is the primary source of water for the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States, which includes the city of St. George. Washington County is the largest employment center in southwest Utah, with a population of 200,000 that is expected to double by 2060.

It’s also the hottest and driest county in Utah, and it’s dependent on a singular water source: the Virgin River Basin. But the Virgin’s waters are thinning from climate-change induced drought and overuse. Water conservation is necessary to meet the increasing demands of growth, and Washington County boasts some of the toughest measures in Utah — including a bold program to “buy” residents’ grass as a way to get them to swap in less water-dependent plants.

Water-efficient landscapes are a key part of Washington County’s efforts to reduce water use. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

Water-efficient landscapes are a key part of Washington County’s efforts to reduce water use. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

Grass is thirsty. Statewide, 70 percent of residential culinary water is used on lawns. By shifting landscaping away from grass and to plants more readily adapted to the climate, residents can reduce landscape watering to nine gallons per square foot annually, compared to 37 gallons for conventional turf.

The Washington County Water Conservancy District began its turf buyback program in December 2022. “Utah is now on the front lines of water conservation,” says Doug Bennett, conservation manager for the district and a leader in developing turf buyback programs across the West. “The turf buyback program is at the forefront of the county’s conservation strategy. Conservation doesn’t require expansion of infrastructure, making it the most cost effective water supply strategy.”

Bennett credits the success of Washington County’s program to a streamlined, incentive-based system. He explains, “I like to say it’s as simple as check in, dig in, cash in.” Residents first register for the incentive program. Next, the conservancy district sends someone to document the square feet of turf to be replaced on the property. Residents then have one year to complete their projects. When the yard is ready, there is one more county inspection. The resident receives a check a few weeks later.

Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

By shifting landscaping away from grass and to plants more readily adapted to the climate, residents can reduce landscape watering to nine gallons per square foot annually, compared to 37 gallons for conventional turf.

The payout is $2 per square foot of converted turf, up to 5,000 square feet. After that, the rate is $1 per square foot. That money is cost-shared between the Washington County Water Conservancy and the state of Utah, which matches the county dollar for dollar. The Utah Legislature allocated $8 million dollars to launch the program, with $3 million recurring annually. To maintain and grow the program, proponents are requesting an additional $12 million from the state legislature.

Participants can select from an extensive list of native plants that are adapted to need less water, including fragrant sagebrush, yucca, succulents and wildflowers like the firecracker penstemon. There are some specific parameters to qualify for the program, such as installing drip irrigation. Mulch must be placed on the soil’s surface to reduce evaporation. At maturity, plants must cover 50 percent of the project area. Non-permeable barriers like concrete and plastic are not permitted because they prevent rainfall and air from passing through the soil. Bennett notes, “We want the plants to thrive!” Artificial turf is allowed, so long as it has perforations for water and air. The program also requires a conservation easement for the property, to ensure that current or future residents will never return grass to the project area.

Blooming cacti at Red Hills Desert Garden in St. George. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

Blooming cacti at Red Hills Desert Garden in St. George. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

To date, 2,044 applications have been submitted and 918 projects completed in Washington County. “We’re projecting that by the end of 2024, our program participants will have transformed enough nonfunctional lawn to be equivalent to a roll of sod about 280 miles long,” Bennett says. “Collectively, these projects should reach 100 million gallons in annual savings by year’s end.” That is enough water to supply 520 single family households.

Bennett recognizes that increased education will boost public participation. He recalls the slow start when Las Vegas launched a similar program: “In 2000, nobody cared. Then in 2002, the drought was so severe that the Colorado River produced just 25 percent of its typical runoff.” (That same drought across the Southwest has persisted for two decades and is known to be the worst in 1,200 years.) Twenty-two years later, Las Vegas’s daily per capita water use has been cut in half. “It was unprecedented for a community [to] save that much without actually just shutting off the water,” Bennett says.

Since 2000, Washington County has reduced per capita water use by 30 percent, the most significant decrease in Utah. Bennett attributes this success to the realities of living in the desert: “Our residents live on the northern edge of the Mojave Desert, and it’s pretty conspicuous by the native terrain,” he explains. In other words, they have “relatively high awareness of the scarcity of water” they face because the landscape itself provides constant reminders.

That’s not the case elsewhere in Utah. “The other major population centers are in the northern part of the state, characterized by mountain ranges, cold and snowy winters and a perception of water abundance,” Bennett says. “Most recently, drought conditions that affected the Great Salt Lake have escalated awareness of hydrologic conditions in northern Utah.”

Under the requirements of the turf buyout program, artificial turf is allowed as long as it has perforations for water and air. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

Under the requirements of the turf buyout program, artificial turf is allowed as long as it has perforations for water and air. Credit: Washington County Water Conservancy District

Despite Washington County’s per capita water savings, because of its rapid growth and development, its overall water use has still increased by 15 percent since the turn of the century. In short, existing water conservation measures do not fully offset the pressure that growth is putting on the water system. This has pushed the county to set the strictest ordinances for new construction and landscaping in Utah. The county now limits lawns to eight percent of property size on all new residential developments. There is a total ban on “nonfunctional grass” at new commercial, institutional and industrial developments. This even prevents new golf course developments. (The caveat is that golf course developers must come up with their own non-potable water source and secondary recycled water sources for irrigation.) The county also reuses water to irrigate public spaces like parks, schools, golf courses and county facilities.

Through turf buyback and other conservation measures, Washington County aims to reduce per capita water use by another 14 percent by 2030. The county also has a 20-year plan to diversify and conserve water sources, which includes tiered water rates, water recycling and education.

Credit: CSNafzger / Shutterstock

Thanks to the desert landscape that surrounds them, Washington County residents are well aware of the scarcity of water they face.

As part of this effort, the new Chief Toquer Reservoir is under construction 20 miles northeast of St. George. The $75 million project, slated for completion in 2025, includes a 19-mile underground pipeline intended to retain up to 3,500 acre-feet of water that is currently lost to seepage at nearby Ash Creek Reservoir.

Meanwhile, a controversial proposal for a 143-mile Lake Powell pipeline, which would import 86,000 acre-feet of water to Washington County, has not progressed amid ongoing efforts to maintain adequate water levels in the reservoir. This was previously considered the savior of Washington County’s water woes, but the hamstrung project has pushed the region to look toward conservation instead. Despite last winter’s above average precipitation, the Colorado River’s Lake Mead and Lake Powell — the largest reservoirs in the country — are only at 36 and 31 percent of capacity respectively.

The North Fork of the Virgin River is responsible for carving the iconic Zion Canyon. Credit: Stephen Moehle / Shutterstock

The North Fork of the Virgin River is responsible for carving the iconic Zion Canyon. Credit: Stephen Moehle / Shutterstock

The Colorado River supplies water to 40 million people across its basin. The Virgin, a tributary of the Colorado, cascades from a cave tucked high in the pink cliffs of the Markagunt Plateau, before flowing through Zion National Park on its way to a 500-million-year-old gorge. On its descent, it enters seven reservoirs that distribute water across Washington County. One hundred and sixty miles from its source, the remaining water arrives at Lake Mead in the northern Mojave Desert.

High demand and aridification have reduced the Colorado River system’s flows — including the Virgin’s. Utah is one of seven states (along with Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming) that must cut down on Colorado River consumption and create a new drought management plan by 2026. While the states don’t yet align on the best approach, there is one water conservation effort they all agree upon: to reduce non-functional turf by 30 percent.

In 2023, the Utah Legislature approved a water-efficient landscaping program as part of the state’s goal to reduce per-capita water use by 25 percent by 2025. Utah is implementing landscaping parameters that restrict lawns to no more than 50 percent of a landscaped area in new residential developments (still much higher than Washington County’s eight percent.) Three other water conservancy districts in Utah have implemented landscaping ordinances, but they are not as expansive as what is included in Washington County’s program. “The state funding may not be used on parks or golf courses, but Washington County’s program includes them,” Bennett notes. “We also rebate conversion of manmade water features such as swimming pools, ponds and ornamental streams.” The county also created its own customer engagement process, which Bennett points to as one reason that participation has been higher here than in the other districts: “It makes it a bit easier for customers to communicate with our program and understand the status of their project.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

While removing turf can make a big difference in residential water use, that alone cannot shoulder the burden of reducing water consumption. The majority of Washington County water is used for irrigation; statewide, a whopping 68 percent of diverted water is used to grow alfalfa for the beef and dairy industry. This is even higher than other Colorado River states, which utilize an average of 46 percent of water diverted from the river to grow alfalfa and other cattle feed crops. A recent study shows that reducing demand for these products can create some of the biggest water savings from citizens.

And while turf buyback programs and other water conservation measures are designed to ensure an adequate water supply for a growing population, it’s also important to consider a more fundamental need: to keep water flowing in the Virgin River. The river shapes the iconic landscape of Zion National Park, which draws five million visitors per year, and supports wildlife habitat within the park and beyond. Six native fish call the Virgin River home, two of which are endangered.

The Nature Conservancy’s Sheep Bridge Nature Preserve supports two miles of the Virgin River corridor. Credit: Stuart Ruckman

The Nature Conservancy’s Sheep Bridge Nature Preserve supports two miles of the Virgin River corridor. Credit: Stuart Ruckman

“There are tremendous water demands on [this] small river,” explains Elaine York, West Desert regional director for The Nature Conservancy in Utah. York says a significant portion of the river between Zion and St. George is conserved, meaning owned and managed by organizations or government agencies to maintain a relatively natural state and function as part of a healthy river system. This includes two parcels purchased by The Nature Conservancy, which is working with the Virgin River Program — a collaborative effort between local, state, and federal partners — on efforts to balance human water use with conserving the Virgin River ecosystem and protecting native (and some endangered) species. Among these projects, The Nature Conservancy is working with Hurricane, a small city near Zion National Park, to fund and redesign a more efficient water delivery system that reduces water loss during transport.

While grass buyback programs alone won’t save the Virgin or the Colorado River, they are an effective way citizens can cut their daily water use — and a clear demonstration of how successful and lasting changes in water use can begin with government-led incentives that incite broader cultural shifts. For now, Bennett is encouraged by Washington County’s buy-in to rip out turf. “Southern Utah residents have been very receptive to water conservation measures,” he says. “The projects we’re seeing are proof that we can sustain an even higher quality of life while leaving a smaller footprint on our watersheds.”

The post This Utah County Will Buy Your Lawn to Save Water appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Moroccan Farmers Are Banking Traditional Seeds for a Hotter, Drier Future

Ibrahim Fajea’s family is one of 131 families remaining in a small community of subsistence farmers in Sidi Ifni on the west coast of Morocco, on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Nestled in the north African country’s Guelmim province, Fajea’s land has suffered from a debilitating drought for almost six years, which drove many farmers away.

Originally from Tighmert, about 75 kilometers south of Sidi Ifni, the 42-year-old and his family of five have been struggling to keep food on the table.

“When the water dried up in the oasis many families were forced to leave,” Fajea says. “I worked with a few people in our farmers’ collective to dig three wells to use groundwater for irrigation.”

Sidi Ifni is a seaside town in Morocco’s Guelmim province. Credit: Tupungato / Shutterstock

Sidi Ifni is a seaside town in Morocco’s Guelmim province. Credit: Tupungato / Shutterstock

But keeping farming alive in this region requires more than just wells. That’s why Fajea is one of a hundred farmers participating in an ecological seed bank initiative by Dar Si Hmad Foundation to help his farming community. Launched in 2021 in Sidi Ifni, the seed bank sources indigenous seeds from across Morocco and Europe. By focusing on traditional, drought-resistant varieties and carefully storing the seeds, the seed bank — and an accompanying training program for farmers — is helping to revive the land and improve the livelihoods of those who rely on it.

A report published by the European Union’s Joint Research Council (JRC) in February warned that after six years of drought, including over two years of severe drought, Morocco has been designated as an area of “severe concern.”

The drought has taken a toll on Morocco’s vital agricultural sector, which generates 14 percent of the country’s export revenue and employs about a quarter of the population, leading the government to implement emergency measures to address the economic and social repercussions. These include price inflation of agricultural products, low yields of food crops and rural exodus.

A dry river valley near Sidi Ifni. Credit: Lars Spangenberg / Shutterstock

A dry river valley near Sidi Ifni. Credit: Lars Spangenberg / Shutterstock

From 2018 to 2023, the country grew drier and drier, with average water flows falling by more than half, putting the majority of the country’s 155,000 hectares of farmland in jeopardy.

Furthermore, small subsistence farmers, 88 percent of whom depend entirely on rain to cultivate their crops, face yet another challenge: reliance on expensive, imported, genetically modified seeds that are ecologically mismatched with Morocco’s critically parched reality.

According to a report by the International Energy Agency, the average annual temperature in Morocco increased by 1.7 degrees Celsius between 1971 and 2017, and in the past five years, the increase reached 1.8 degrees, leading to a crisis in both drinking water and water for irrigation, hence the threat of serious food insecurity.

The situation will worsen as the country approaches the absolute scarcity threshold of water, which is 500 cubic meters per person annually, by 2030, according to a World Bank report.

Credit: Roserunn / Shutterstock

Morocco has grown increasingly dry in recent years, with average water flows falling by more than half between 2018 and 2023. Coupled with rising temperatures, this has led to a water crisis.

Yet despite government plans and a series of initiatives launched to raise awareness about water conservation, aquatic engineer Faisal Aziz believes it’s not enough.

“We need tight regulation to curb the depletion of natural resources,” Aziz says. “This means implementing strategic governance of human activity, specifically in agriculture.”

Aziz is addressing Morocco’s export-oriented government policy, which he says has exacerbated the country’s levels of water stress through the cultivation of lucrative export produce that consumes tremendous amounts of water.

“One kilogram of watermelon requires 45 liters of water using drip irrigation technology, which means that a 10-kilogram watermelon could consume 450 liters of fresh water,” Aziz explains. “The same applies to avocado, where one kilogram requires over 700 liters of water.”

Mountains of fruit at a market in Sidi Ifni. Credit: mhobl / Flickr

Mountains of fruit at a market in Sidi Ifni. Credit: mhobl / Flickr

Aziz says that both public and private sectors should invest in acquiring non-traditional water resources like wastewater treatment or desalination plants, in addition to supporting scientific research on sustainable solutions.

Fajea plows the land the way his ancestors did generations ago. “I use organic fertilizer produced from livestock and poultry,” he explains, as he extolls the benefits of agroecology, ecological agriculture that uses no chemicals and respects the rhythm of the seasons and natural biodiversity. Such practices are growing more popular in Morocco, albeit slowly: The most recent survey data shows that agroecology went up from 4,000 hectares in 2010 to 10,000 in 2020, accounting for just over six percent of Morocco’s total agricultural land.

“But it all begins with the seeds,” Fajea says. The seeds collected for the seed bank are meticulously stored in a specially designed space. Crafted from sun-dried clay, the space draws on historical Moroccan architectural methods.

Rooted in tradition, the special climate conditions multiply the seed yield at a higher rate, preserving native seeds adapted to the local environment. Traditional varieties of corn, wheat and alfalfa, for example, are drought-resistant, and require fewer resources, enabling farmers to produce more with less.

Courtesy of Dar Si Hmad Foundation

The building that houses the seed bank was specially designed to maintain the climate necessary to preserve the seeds. It was made in a traditional style with sun-dried clay.

This seed library, which the foundation calls Tin’Amoud, Amazigh for “mother of seeds,” is the first of its kind in the region. It is a space for safeguarding local heirlooms and perpetuating the tradition of bartering and sharing seeds that are unique and adaptable to the dry and semi-dry local conditions, explains Ouafegah.

“The foundation retains half the quantity of the first and second generation of seeds for storage in the clay houses,” he said. “The other half is given to the farmers to cultivate. The third generation of seeds can be stored for two to three years.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

These seeds are kept in jars with information cards, a traditional method that requires complete shade and temperatures that do not exceed 26 degrees Celsius. The only danger is insect infestation, which could result in poisoning the seeds, explains Ouafegah.

The seeds are kept in jars in a shaded space at 26 degrees Celsius or lower. Courtesy of Dar Si Hmad Foundation

The seeds are kept in jars in a shaded space at 26 degrees Celsius or lower. Courtesy of Dar Si Hmad Foundation

Though it will require several more seasons to fully measure how the seed bank initiative has improved yields, already, farmers have benefited significantly. Their produce is now fully organic, making it more marketable. And as the seed bank allows them to preserve more seeds with mother genes over the years ahead, they will grow increasingly self-sufficient, no longer relying on imported seeds, which require more water and the use of pesticides.

“Preserving the mother genes of these seeds is the best way to avoid a food crisis in the future,” Ouafegah says, lamenting the fact that 95 percent of seeds used in agriculture in Morocco are currently imported.

As part of the initiative, Fajea and the other participants completed a farmer agroecological training program called Afous Ghissiki, an Amazigh phrase meaning “the hand in the abandoned land.” Afterward, Fajea says, the trainer from the foundation taught them how to market their organic products.

“We were introduced to foreign families and tourists who are more interested in buying our natural, organic products than the locals,” he says.

The initiative creates sustainable livelihoods for both the farmers and their environment, Dar Si Hmad trainer Mustapha Ouafegah explains: “We teach farmers how to revive the land, using natural agricultural pesticides suitable for dry conditions and poor irrigation.”

When it comes to efforts like the seed bank, sustainability is only one advantage, says Jihad Malih, an expert in eco-farming. “These seeds have a greater ability to pass on their genes to subsequent generations of seeds and to adapt to any weather conditions, whether it’s drought, poor irrigation or even excessive heat,” Malih says. “They also have significantly more nutritional value compared to genetically modified seeds and are healthier for consumers.”

Courtesy of Dar Si Hmad Foundation

Farmers who participated in the Afous Ghissiki ecological training program and now growing fully organic — and therefore more marketable — produce.

Malih refers to the famous study conducted by Donald Davis, professor at the Biochemical Institute at the University of Texas in Austin, who compared data gathered by the US Department of Agriculture in 1950 and 1999 on the nutrient content of 43 fruit and vegetable crops. Davis found that six of 13 nutrients studied (phosphorus, iron, calcium, protein, riboflavin and ascorbic acid) had declined by between nine and 38 percent.

“Genetically modified seeds also limit a farmer’s independence, who must buy new seeds every season,” says Malih. “Imported seeds also require more water and chemical pesticides.”

Jamila Bargach, anthropologist and executive director of Dar Si Hmad foundation who holds a PhD from Rice University, has even bigger dreams for the farmers of Sidi Ifni. “Our aim,” she says, “is to produce seeds from local varieties and distribute them freely through a system of bartering and free sharing among farmers. This is how we create a new dynamic in the consumption and production chain and eventually achieve grain sufficiency and food independence.”

This article was produced in collaboration with Egab.

The post Moroccan Farmers Are Banking Traditional Seeds for a Hotter, Drier Future appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Planting Trees and Equity in the Arizona Desert

On a recent Sunday morning, the Barrio Centro neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona, was abuzz with activity. People from all walks of life were busy hauling dirt, planting saplings and building earthworks like berms and swales in the warm spring air.

They were part of a community planting event organized by Tucson Clean and Beautiful, a local nonprofit, as part of a larger, city-wide effort to fill street corners and vacant lots with groves of trees. The ultimate goal: to create more shade and increase heat resilience in the most vulnerable neighborhoods.

Tucson, sitting in the middle of the Sonoran Desert, is among the fastest-warming cities in the US. Over the past five decades, its average temperature has soared by 4.48 degrees Fahrenheit; last year, the town sustained more than 50 consecutive days with temperatures surpassing 100 degrees.

Youth employed by Tucson Million Trees work to place and irrigate young trees. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Youth employed by Tucson Million Trees work to place and irrigate young trees. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

However, the heat hits some areas harder than others. In neighborhoods in southern Tucson such as Barrio Centro, predominantly home to Latino and low-income communities, temperatures can be up to eight degrees warmer than the city’s average and a staggering 12 degrees hotter than affluent areas in the city’s north like the Catalina Foothills.

Such a difference is the legacy of decades of neglect that prevented the development of green spaces in the city’s poorer neighborhoods, argues Fatima Luna, Tucson’s chief resilience officer. “The south part of Tucson has been historically under-resourced, and there are not a lot of tree canopies there,” she says.

The extra heat endured by low-income neighborhoods often coincides with limited access to air conditioning, putting residents at risk of heat-related illnesses and even death. “This isn’t merely an environmental issue,” maintains Luna. “It’s a critical public health concern.”

Planting sessions take place from October through March. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

Planting sessions take place from October through March. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

To address these disparities, in 2020 Tucson set a lofty goal: to plant one million trees by the decade’s end. The commitment came as the city joined the 1t.org Stakeholder Council, a coalition dedicated to global tree restoration efforts. The US chapter of this council — which includes organizations like REI, the National Forest Foundation and Amazon, and cities like Dallas and Detroit — has pledged to plant over one billion trees collectively.

To pinpoint the areas most in need, Tucson city officials rely on an interactive dashboard powered by American Forests’ Tree Equity Score methodology. The tool crunches data like tree canopy cover, climate, the percentage of people of color, poverty rates, unemployment rates and the population of seniors and children to produce a single measure ranging from zero to 100 for each of Tucson’s 466 neighborhoods.

“This score serves as a compass, highlighting areas needing urgent attention,” Nicole Gillett, Tucson’s urban forestry program manager, explains. “Lower scores signify a greater need for investment.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Accessible to the public, the dashboard facilitates transparency and citizen engagement, enabling residents to track progress and report planting activities.

Planting sessions, organized in collaboration with local organizations such as Tucson Clean and Beautiful, occur on weekends throughout the planting season, which spans from October to March. During these events, volunteers are mentored by professional arborists who provide instructions on tree planting and maintenance.

Through a platform called Grow Tucson, residents also have the opportunity to actively co-design urban green spaces, ensuring they meet the needs of their community.

To date, about 100,000 trees have been planted. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

To date, about 100,000 trees have been planted. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

“Giving locals a personal stake is crucial,” notes Gillett. “It fosters purpose.”

The initiative prioritizes planting drought-resistant species indigenous to the region, such as blue palo verde, desert ironwood, desert willow and desert hackberry. “These species are particularly suited for urban environments because they grow at low elevations and depend entirely on rainwater for nourishment,” says Gillett.

In Tucson, where much of the surface is paved and impermeable, planting these trees can even play a role in revitalizing the city’s beleaguered streamsheds rivers, and creeks.

“Adding a rain basin with every tree is like giving the rain a direct pathway into the ground where it’s needed,” explains Gillett. “That way, it’s not just watering the trees but also replenishing groundwater and supporting streamflow.”

Some of these tree species can also contribute to addressing food insecurity in a city where nearly 20 percent of residents live more than a mile from the nearest grocery store, believes Brandon Merchant, a longtime Tucson resident and farm and garden education coordinator for the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona.

Merchant leads a program called SOMBRA, the Spanish word for shade and an acronym for Sonoran Mesquite Barrio Restoration Alliance. The initiative aims to plant 20,000 velvet mesquite trees across the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods by 2030 to build shade and enhance food security.

Young native species being grown for future planting. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Young native species being grown for future planting. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Backed by the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management’s Urban and Community Forestry Program and the US Forest Service, SOMBRA began in 2021 after Merchant drew inspiration from a similar initiative in Portland, Oregon, focused on chestnuts.

“When we started thinking about it, we began noticing that mesquite trees are very much like chestnuts in that they can be grown in cities and can be used as a food supplement,” explains Merchant. “Indigenous communities living in this area have relied on it for thousands of years.”

The food bank organizes workshops about growing, pruning and harvesting techniques to educate community members on planting and caring for mesquite trees. “That’s a big part of it, giving people the skills to plant and tend to these trees for the long haul,” Merchant explains. The training also involves processing mesquite bean pods into flour ideal for baking bread, cookies and pancakes.

As part of the initiative, Merchant has teamed up with a local high school, a community farm and representatives from local tribes. Together, they have set up four cultivation sites where saplings are grown and nurtured until they are ready for transplantation. Only a few hundred saplings have been put into the ground thus far, but Merchant is optimistic about scaling up planting efforts this year.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

To date, Tucson’s initiative has led to the planting of approximately 100,000 new trees. Gillett says some of the trees planted first will start to have a small impact on shade and temperature, but it will take several more years to fully measure their impact.

The effort recently received a significant boost with a $5 million grant from the US Forest Service. This funding is part of a larger $1 billion commitment to urban forestry projects nationwide, established under the Biden administration’s flagship Inflation Reduction Act.

In addition to providing shade, mesquite trees can help alleviate food insecurity thanks to their bean pods. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

In addition to providing shade, mesquite trees can help alleviate food insecurity thanks to their bean pods. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

The grant funding will help the city run its recently opened Tree Resource Education and Ecology Center, a hub where seedlings are nurtured, and which can accommodate approximately 5,000 trees and plants. According to Gillett, this financial support will also bolster tree-planting capabilities and contribute to youth employment through specialized training initiatives.

As Tucson paves its path toward a cooler and more resilient future, municipalities across the country are paying attention. Gillet says she is frequently approached by leaders interested in setting up similar schemes in their own cities.

She believes Tucson’s approach can serve as a guiding model, as long as efforts are rooted in scientific principles, involve residents at every stage, and prioritize supporting vulnerable communities. “We’re not just planting trees,” says Gillett. “We’re planting equity.”

The post Planting Trees and Equity in the Arizona Desert appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

An Ancestral River Runs Through It

Jeff Wivholm isn’t partial to mountains. He likes to be able to see the weather rolling in, something remarkably possible in the northeastern corner of Montana.

On a cold January morning, Wivholm drives the dirt roads between farms in Sheridan County, where he’s lived for all his 63 years, with practiced ease, pointing out different plots of land by who owns them. And if he doesn’t know the family name, Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District or Brooke Johns with the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge — both sitting in the backseat of his truck — can supply it.

If you look to the right there, Wivholm says, you can see the valley created by the aquifer. Maybe he can, his eyes accustomed to seeing dips and crevasses in, to an unfamiliar eye, a starkly flat landscape. He laughs and says it takes some getting used to.

That aquifer isn’t unique in Montana. There are 12 principal aquifers running like underground rivers throughout the state. But the way Sheridan County uses the water is.

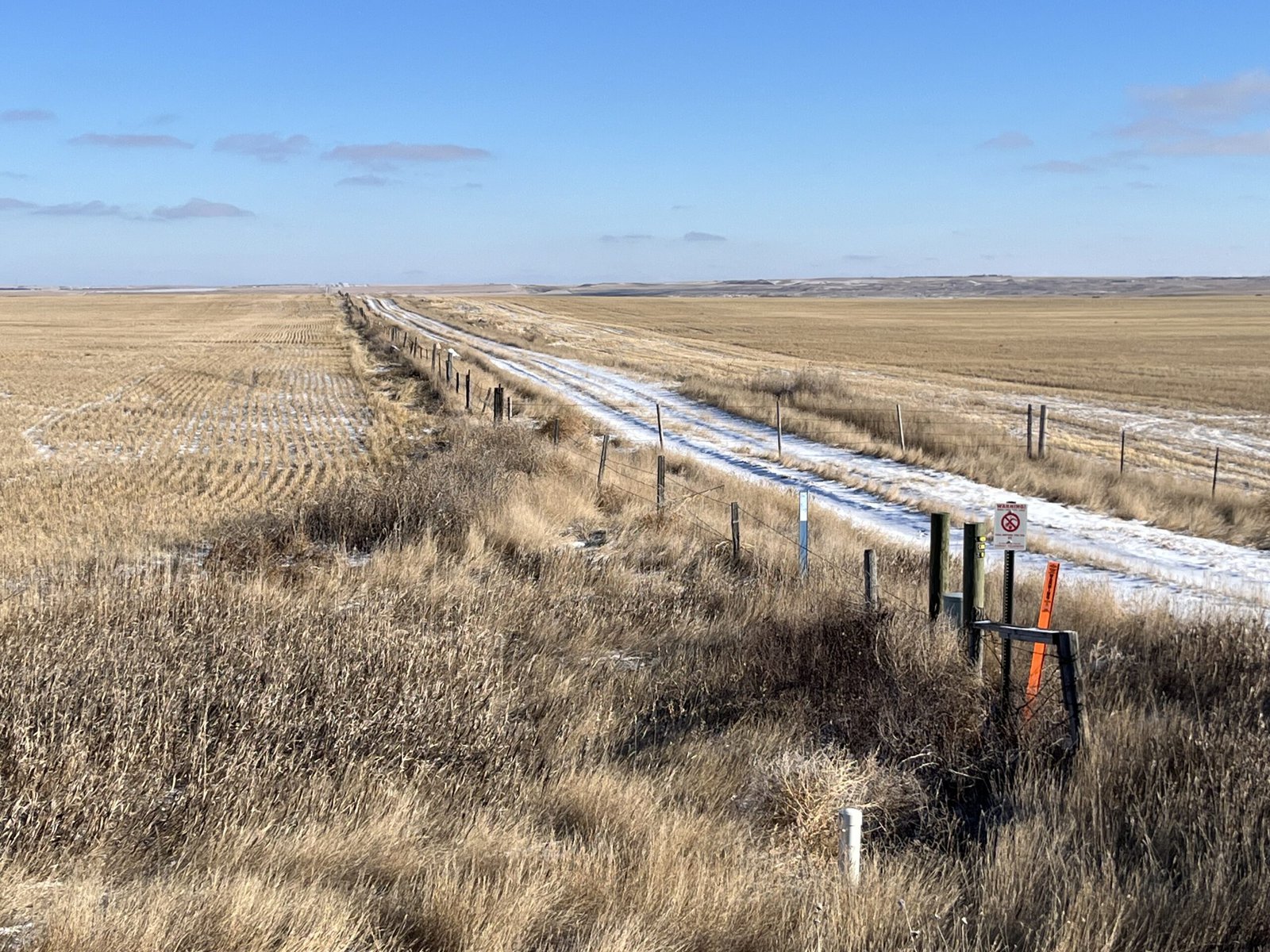

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

Montana is in relatively good shape as far as its groundwater supply goes, something uncommon across much of the country, geologist John LaFave with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology says. State politicians initiated a groundwater study over 30 years ago after years of intense drought and fires and a lack of data.

But Sheridan County was ahead of the game: The county’s conservation district started studying its groundwater in 1978, before state monitoring began.

In 1996, the district was granted a water reservation, or water allocated for future uses, from the state, which meant it could take a certain share of water from the Clear Lake Aquifer. Because of all the data it gathered through studying its groundwater, the district developed a unique way of using and distributing that water.

What’s unusual is how intentional the collaboration was and how extensive the groundwater monitoring was and continues to be. The district does this by working with farmers, tribes and the US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) to ensure water can be used by those who need it — those who would be most affected by any degradation to the water — without negatively impacting the environment.

And it’s worked. The conservation district has been using its geologically special aquifer — a gift granted to this area by the last Ice Age — to irrigate crops, provide jobs for the region and keep agriculture dollars within the community for almost 30 years while fielding few complaints.

“To me, this represents the way groundwater development should occur,” LaFave says.

Sheridan County is extremely rural, home to about 3,500 people across its 1,706 square miles. Agriculture is a big economic driver. Bird hunting is an attraction for locals and visitors. The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located in both Sheridan and Roosevelt Counties and managed by the USFWS, is home to many migratory bird species. It’s the largest pelican breeding ground in Montana and the third-largest in the country.

This early January morning, it’s about five degrees, but there isn’t a lot of snow on the ground. Over coffee and breakfast in Plentywood — the county seat — Yoder and Wivholm say this winter has been warmer and drier than usual.

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

Dry weather is not uncommon here. Droughts in the 1930s and ’80s were particularly rough. Also in the ’80s, irrigation technology was becoming more common and efficient, Wivholm says, and people began to pay more attention to the possibility of an aquifer as a way to ensure water would be available for irrigation.

“There are several nicknames for much of this property, but it was basically ‘poverty flats,’” Jon Reiten, hydrogeologist with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, says. The soil is sandy, gravelly and drought-prone. Not great for dry-land farming.

Marlowe Onstead was the first farmer in Sheridan County to use the aquifer for his pivot irrigation in 1976.

“Couldn’t raise the crop on it before,” Onstead says. After irrigation, he was able to grow alfalfa.

According to Reiten, the aquifer ranges from a mile to six miles wide and two to three hundred feet deep. The ancestral Missouri River channel, discovered in Sheridan County in 1983 as monitoring began, flowed north into Canada and east into Hudson Bay. That channel was dammed by glaciers in the last Ice Age and left behind a reservoir that was buried as glaciers melted, creating the Clear Lake Aquifer. Since the materials left behind were coarse and varied, water could move easily and be stored in great depths. A downside is that these glacial aquifers can take a long time to refill.

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

As drought dragged on in the ’80s, locals and county and state authorities set about figuring out the best way to distribute the aquifer’s water. Medicine Lake lies on top of some of the aquifer, and the Big Muddy Creek — where the Fort Peck Tribes require a minimum in-stream flow to promote ecosystem health — is at its southwestern border.

The Fort Peck Tribes and the USFWS were concerned about their respective water levels and how they’d be impacted by irrigation. Reiten says the USFWS was objecting to just about every water rights case that went to the state at the time, and all that litigation ended up in water court.

“That’s a lot to put on a producer, to have to go up against the federal government,” Reiten says.

Negotiations with the USFWS and the Fort Peck Tribes led to the formation of an advisory committee and the transfer of the water reservation on the aquifer from the state to the conservation district. (Per Montana water law, all water belongs to the state and individuals are required to get a water right to use it in a particular way — in this case, for irrigation.) Since then, Sheridan County Conservation District has had the authority to give water allocations from the Clear Lake Aquifer to producers without the producers having to appeal to the state.

The maximum amount of water that can be pulled from the aquifer is just over 15,000 acre feet total, a number set by the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Currently, the district is using about 10,000 acre feet. Increases are allowed as long as monitoring shows the aquifer isn’t being overly impacted by irrigation.

Credit: Keely Larson

The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge is home to the third largest pelican breeding ground in the country and the largest in Montana. Negotiations with the US Fish & Wildlife Service, which manages the refuge, helped Sheridan County Conservation District obtain the water reservation for the Clear Lake Aquifer.

“We were basically forced to monitor it, but it only makes good sense,” Wivholm, who has been on the conservation district board since 1994, explains. The district wouldn’t want to grant someone a right only to find out in five years that there’s not enough water.

Once a year, the committee meets to assess new water rights. The committee includes the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, the state Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, representatives from the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, county commissioners, a county planner, the Fort Peck Tribes and a representative with the United States Geological Survey.

If a farmer wants an irrigation pivot, they have to “pump it hard for 72 hours,” Wivholm says, to make sure there is enough water for their request, and understand how that pumping affects other wells nearby.

Data comes from Yoder’s efforts. She collects readings from data loggers placed in the ground throughout the county from April through October. For the first and last collections, she visits 201 wells and it takes her three 12-hour days to get to them all. Driving around in Wivholm’s truck, she points out some of her data loggers sticking up from the ground every few minutes.

Through monitoring, Sheridan County Conservation District and the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology have been able to map the entire aquifer. They take note of the water levels, monitor each irrigation pivot and can see seasonal fluctuations.

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

“It’s kind of a hidden resource, but the amount of crops that we can get off of the poor ground that is above the aquifer is amazing,” Yoder says. She lists corn, wheat, chickpeas, lentils, canola, mustard and alfalfa.

Another farmer in the area, Rodney Smith, has been irrigating from the Clear Lake Aquifer for over 35 years and has the biggest pivot connected to the aquifer.

Smith says irrigating has been economically beneficial: His farm isn’t as dependent on the weather, and it’s taken the risk out of production. Smith Farms Incorporated produces hay for livestock and sells it to other ranchers in the area. Smith also leases land out to other farmers who grow potatoes and sugar beets.

From an aerial view, his circular pivot plots show different colors of green and brown, indicating a variety of crops grown.

Smith had an early contested pivot case with the state of Montana, before the water reservation was transferred to the conservation district, which went to the state water court.

The gist of the case was that Smith Farms wanted to change their method of irrigation and the USFWS was concerned it might impact the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Data and monitoring done by the conservation district backed up Smith’s case.

“When you start irrigating, you wonder what is the capacity, or how much can you irrigate,” Smith says. “It’s always interesting to know what it’s doing.”

Credit: Google Earth

Land that is irrigated with pivot irrigation shows up in circular plots from above due to the way the structure pivots around a fixed point. Here, the circular pivot plot is sliced into different colors where different crops or phases of harvest have occurred.

Johns, with the wildlife refuge, says the refuge has a water reservation on Medicine Lake and is allowed to keep the lake filled for the protection of migratory birds. The refuge operates dams and diversions to maintain this need. Making sure any irrigation wouldn’t draw down the level of the lake has been a goal from the beginning, Johns says, and so far, that hasn’t been an issue.

There haven’t been any other contested cases on aquifer irrigation, and many, including Smith, see this as a success in having local control over a local resource.

“Water rights are such a contentious thing,” Johns notes. “And without the data, had they not started this years ago, it would be hard to start it today and get the same momentum they did.”

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Arnold Bighorn, water rights administrator for the Fort Peck Tribes, says the collaboration between all those affected by the aquifer — counties, tribes and the wildlife refuge — has worked well.

“Everybody’s on the same page, which is good,” Bighorn says.

Monitoring groundwater like this is unique in Montana, according to Reiten, particularly for irrigation development. But there are successful examples in other states.

Before he came to Montana, Reiten worked for the North Dakota State Water Commission, where the same type of monitoring was going on that he helped start in Plentywood. He is working on another aquifer in Sidney, Montana, about 85 miles south of Plentywood, to develop a similar system.

“We’re applying the same methods there to try to develop that aquifer without affecting anything else,” Reiten says.

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Many conservation districts across Montana have water reservations on surface water, Yoder says, but Sheridan County Conservation District is one of only two districts that manages a groundwater reservation.

“I haven’t heard of any other places that have quite the extensive monitoring that we have and the time range that we have,” Yoder says.

There continues to be room for more water and improvement in how it’s used.

Wilvhom would like to see soil monitoring, so producers can know when to water and when they’re using too much. Devices are available that farmers could bury in the ground to monitor soil moisture and temperature.

Managing the aquifer has been “a collaboration to help the whole community do good,” Wivholm reflects later in the week, when Plentywood has reached -58 degrees with a windchill. “It helps the whole health of the whole ecosystem.”

The post An Ancestral River Runs Through It appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.