nature

Could You Transform Your Yard into a Flourishing Wildlife Haven?

Four years ago, Melody Murray started noticing these cute signs in her Portland, Oregon neighborhood of Sullivan’s Gulch. Posted in residents’ front yards, the signs read: “Certified Backyard Habitat” with a drawing of a black, red and white spotted towhee sitting on a leafy branch.

“I didn’t know what they were for,” says the Ohio native who moved to Oregon in 1994. Her curiosity piqued, she went online and quickly found out: The Backyard Habitat Certification began as a joint project of Columbia Land Trust and Portland Audubon (now called the Bird Alliance of Oregon) to encourage urban residents to garden without pesticides, plant native plants and remove invasive species. All of these practices support a flourishing community of native birds, insects and other wildlife.

Trillium in Melody Murray’s yard. Courtesy of Melody Murray

Trillium in Melody Murray’s yard. Courtesy of Melody Murray

When Murray lucked into a one-acre property in the Cully neighborhood in 2021, she joined the Facebook group “Friends of Backyard Habitats,” where she lurked for a while until she felt ready to sign up. Because she and her partner had already cleared away invasive plants like ivy and vinca (periwinkles) — and planted an array of native trees, shrubs and plants — they got certified at the “Silver” level as soon as the Backyard Habitat technician could come for a site visit.

“It was super easy for me because I had already made an effort to remove the ‘bad guys,’” says Murray, who was already a skilled gardener. “There were other bad guys. But I had enough native stuff that it tipped the balance.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Since the Backyard Habitat program launched in 2009, 14,000 properties have enrolled in the Portland metro area. (It covers Clackamas, Clark, Multnomah and Washington counties.) The program began as a pilot project in the Southwest hills neighborhood as a way to get neighbors to keep their ivy and blackberry plants from crawling over fences. The habitat signs were a helpful incentive from the start, along with certification, resources and discounts. It worked so well, says Peterson, that the city of Portland wanted to take it city-wide. That’s when Portland Audubon came in as a partner.

After Melody Murray and her partner cleared away invasive plants and planted an array of native trees, shrubs and plants, they got certified at the “Silver” level. Credit: Backyard Habitat Certification Program

After Melody Murray and her partner cleared away invasive plants and planted an array of native trees, shrubs and plants, they got certified at the “Silver” level. Credit: Backyard Habitat Certification Program

The program, which costs no more than $45 to join, is relatively straightforward. (There’s a sliding scale so that people who can’t afford $45 can pay less. There’s also an option to pay more than $45 to pay it forward.) Once a resident fills out an enrollment form and pays the fee, a habitat technician will come to their house for a site visit. They’ll look closely at the resident’s yards — contrary to the name, the certification covers not just a person’s backyard but front and side yards, as well — and give pro tips on creating habitat for wildlife, managing stormwater, decreasing pesticide use and removing nuisance weeds. They also recommend ways to increase the percentage of “naturescaped areas.” Naturescaping is a gardening practice which emulates nature, so the idea is to select plants that are native, in this case, to the Willamette Valley ecoregion. These plants have adapted to the local climate and are naturally resistant to pests and diseases. They also provide food and shelter to support the entire life cycles of pollinators and birds they have evolved with. As a bonus — and a win for lazy gardeners — they require less maintenance and help manage stormwater. The Backyard Habitat program also asks that each participant have at least three native canopy layers present. (Canopy layers are composed of tall shrubs, small shrubs, and groundcover.)

Getting rid of nuisance weeds is important because they smother and kill native plants, which local wildlife depend on. One of the most commonly found in gardens in the Portland area is ivy (all cultivars). Though it can look beautiful — who doesn’t like an ivy-draped railing? — it can damage trees and shrubs (which it can completely engulf, eventually killing them), increase erosion and degrade habitat. The one habitat they’re good for is rodents, which love to hide in the ivy. A good native alternative to ivy is oxalis (a.k.a. redwood sorrel), an edible perennial that flowers, or wild strawberry (though it requires full sun to fruit).

All these changes and additions can be intimidating at first. Patrice Ball first applied for certification in 2015. She had just been widowed and she wanted to honor her late husband, who had been a gardener. But after the site visit she felt overwhelmed by all the requirements. She didn’t tackle the invasive plants and eventually sold that house and moved to a smaller one that fit her needs better.

Patrice Ball was pleasantly surprised to learn that her non-native hibiscus tree was not a deal-breaker for certification. Courtesy of Patrice Ball

Patrice Ball was pleasantly surprised to learn that her non-native hibiscus tree was not a deal-breaker for certification. Courtesy of Patrice Ball

At the new property, she began gardening in earnest, with more attention to natives. “I thought, ‘Maybe someday I’ll apply for that,’” she says. One day, she was visiting a friend who had Backyard Habitat Certification and saw a banana tree in her yard. “I said, ‘Now wait a minute. That’s not native,’” she recalls. The friend informed her that certification doesn’t require you to have all native plants, just a certain percentage of your plantable yard. For Silver, that’s just five percent. (Gold is 15 percent and Platinum — much harder to reach — is 50 percent.) In 2022, when a technician came to do a site visit, Ball was pleasantly surprised to hear that she only had to do a few more things.

“When she left, I thought, OK, I have a shot at this!” That fall and the spring of 2023, Ball added the things the technician suggested. In the summer another technician came out to do the second inspection. “I was a little nervous,” Ball recalls. “I thought I’d get the lowest of the three rankings. At the end of the visit, he was like, ‘Congratulations: you got the Gold certification!’”

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Ball had lived in Belize and for nostalgia’s sake she had also planted a hibiscus tree (not native to the Pacific Northwest). Hers was in full bloom at the time of the second site visit, and the technician asked if she could pose in front of it for the official photo, which he’d then put up on the Backyard Habitat social media. “I said, ‘But it’s not native!’ And he said, ‘That’s OK!’” recalls Ball. “Mainly he was like, ‘You’ve done a really good job, you have a water feature, there’s no lights to confuse the birds at night, you have really happy birds.’”

A flicker nesting in Melody’s yard. Courtesy of Melody Murray

A flicker nesting in Melody’s yard. Courtesy of Melody Murray

At the initial assessment, the technician provides a folder full of materials including a native plants brochure, a native plant tracking sheet and coupons for discounts at local nurseries. When they send their site report, the technician also includes a bunch of resources including a link to the Portland Plant List, which is a great way to find native plants and identify nuisance plants, and a link to the Friends of Backyard Habitats Facebook group.

It was a fun project for Murray, who may sign up for Backyard Habitat’s Open Garden tour (where others can tour your garden). “I have a ton of vine maple. I’ve got a couple if native roses. Every variety of Oregon grape you can imagine, Kinnikinnick, a lot of manzanita,” she says. “I’ve also got camas, penstemon, and Oregon white oak.” As if she couldn’t contain her excitement, Murray went on: “I’ve got huckleberry, native blueberries, native blackberries — not the Himalayan ones. Native rhododendrons, serviceberry. Cascara. A whole bunch of different kinds of ferns — every kind of fern you could imagine.”

Having a flourishing yard is just one reward. The other? “My birds and insects have really ticked upwards in a big way!”

The post Could You Transform Your Yard into a Flourishing Wildlife Haven? appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

How Southern Africa’s Elephants Bounced Back

The sun is setting above the horizon in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, but it’s still 40°C (104°F). A large group of elephants has just arrived at a lagoon to refresh themselves and get their daily dose of water: Drink up 200 liters each, and they are good to go. They frolic a little in the water and then set off to search for leaves and grass in the parched savannah, only to be replaced by another herd with many young calves.

While most species’ populations are decreasing, elephants in southern Africa are doing well. A newly released study of 103 elephant populations from Tanzania southwards — the most comprehensive ever — finds that conservation has halted the decline of savannah elephants in southern Africa over the last 25 years. To be more precise, as of 2020, the elephant population had rebounded to the same number as in 1995: 290,000. The scientists found that large, well-protected areas connected to other protected areas are far better than isolated “fortress” parks at maintaining stable populations.

Even though these outer areas don’t have the same level of protection so animals face a higher risk of dying, they are vital corridors that allow the elephants to migrate back and forth when core areas are too crowded or when facing threats such as poaching or unsuitable environmental conditions.

The post How Southern Africa’s Elephants Bounced Back appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The Upside Down: A Tree for Life

Some years ago, when we moved to our current cottage, we were puzzled by the death, one by one, of our hitherto robust, lay-an-egg-a-day-without-fail chickens.

There was no obvious distress. They first stopped laying, then stopped scratching the lawn and, finally, hunched dolefully on their perches, they stopped breathing altogether.

It turned out they had been poisoned by the magnificent male yew tree which dominates our back garden and sheds its toxic leaves and spent flowers across the lawn.

This was a somewhat brutal introduction to the yew’s back story.

They are known as the ‘tree of death’ and almost every part of them – leaf, bark, flower, seed – are extremely toxic. Our chickens were just a small addition to the large number of livestock that die from eating yew foliage each year and, even though a fatal dose for a human would be 50 grams of yew needles – not easy to do by accident – it does happen: even inhaling the sawdust has been known to kill people. The Latin name for the tree, Taxus, shares a root with ‘toxic’ (from toxon ‘bow’, the connection being poisoned-tipped arrows).

This association of yews with death stretches back at least as far as Ancient Greece where the tree was sacred to Hecate, goddess of magic and witchcraft, who was also associated with death. Yews were planted with cypresses and laurels in cemeteries – their roots were believed to seek out the mouths of corpses and to ferry the souls to the afterlife. This idea seems to have emerged in Celtic cultures too, where yew trees were also associated with burial and rebirth.

English churchyards are still full of yews. Because it turns out that the ‘tree of death’ is also the ‘tree of life’.

Yews can live for an unimaginably long time. The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire, Scotland, is estimated to be at least 2,000 years old – some estimates put it at 5,000 years old, which means it was planted during the Bronze Age. At least 10 other British yews are thought to date back to the first millennium.

John Mitchinson's yew tree

John Mitchinson's yew tree

Yews have other miraculous powers that add to this sense of immortality. When most other trees split, they perish because fungal diseases thrive in the fracture. Not so the yew. Indeed, cut the trunk of a yew, or bury one of its long branches in the ground, and vigorous new growth emerges, even on an ancient tree. As Wordsworth wrote in his poem ‘Yew-Trees’, they are:

A living thing

Produced too slowly ever to decay;

Of form and aspect too magnificent

To be destroyed.

But the story of the yew is one of exploitation as well as veneration.

The slow-growing wood is both hard and flexible which makes it perfect wood for longbows. The demands of medieval warfare were such that the population of yews in France and Italy were decimated almost to the point of extinction and have never recovered.

And what of our killer yew? It is easily the oldest living thing in the parish, but it is some way from the churchyard.

Though notoriously difficult to pin down the age of a yew, a rough estimate based on its girth puts it between 600 to 700 years old. That takes us back to the late 14th Century, a period when the village lost almost a third of its population to plague. There is a tradition of yew trees being planted over plague pits, to purify the ground and keep the tainted corpses pinned in the earth. A map from the 18th Century suggests the site of the tree was on one of the main roads leading out of the village. It’s impossible to prove, but the facts fit.

For me, it’s the double quality of the yew that keeps its symbolic dimension so potent. The poison that killed our chickens is extracted to produce Taxol, a life-saving drug used in chemotherapy. The only part of the yew that isn’t toxic is the sweet red berries or arils that surround the toxic seed encouraging birds and animals to eat and pass them unharmed enabling new yews to grow. The dense foliage provides homes to nesting birds and roosting bats but was also believed to harbour sprites and demons. The yew is a constant reminder that life and death are two sides of the same coin.

Modern scholars now think that the World Tree – Yggdrasil – of Norse Mythology was a yew not an ash. Our yew has something of that symbolic immensity to it: it feels like a guardian, a luck-bringer, a home to bats and thrushes and hedgehogs, but also a daily reminder of mortality and the limits of our human scale.

To be honest, having that in your back garden is worth not being able to keep chickens.

‘Rewilding is the Key to Upgrading Our National Parks’

Newsletter offer

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive editorial emails from the Byline Times Team.

Earlier this month, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the world’s most respected environmental network – quietly and brutally downgraded the UK’s protected landscapes (which include our national parks). It followed a decade of "no evidence" that they are effective for nature recovery.

This news slipped under the radar of the established media, while simultaneously ringing very loud alarm bells in the ears of all conservationists, environmentalists and rewilders.

It stings all the more as it comes mere days after the announcement of a new national park as part of the Government's package of measures to improve public access to nature and reverse its decline. This was accompanied by a funding announcement of £10 million for existing national parks and protected landscapes over this year and next.

But those who work in, and for, national parks know all too well how negatively huge cuts in core funding have affected them over the last decade.

It is not simply a case of our national parks being downgraded due to lack of funding, though that is certainly a major factor. It’s more simple than that. There has long been a lack of clarity and a muddled approach to the purpose of our national parks and protected landscapes – what are they for and how should they be managed?

In one way, the answer is obvious: they exist to protect and restore nature. A YouGov survey commissioned by Green Alliance this year revealed that more than 70% of respondents thought the priority of national parks should be providing habitats for wildlife. This reflects polling undertaken by Rewilding Britain in 2021, which found that 83% of the public supported Britain’s national parks being made wilder.

But the reality, which the IUCN’s review so clearly demonstrates, does not reflect this.

When Will the Sea Claim England’s Lowlands? We Don’t Know

As we continue to worsen climate change by burning fossil fuels, all these places will become harder and more expensive to defend – until the day they can’t be defended any more

Charlie Gardner

The majority of our national parks aren’t working to protect and restore nature, and haven’t been for some time. This is very concerning – not least because we all feel a strong collective pride for our national parks and want to see them flourishing, but also because our national parks and protected landscapes are crucial areas if we are to see 30% of land and sea protected for nature by 2030.

This is a key environmental commitment by the Government, one reinforced by the new Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Secretary Steve Barclay when announcing the new national park.

Our national parks and protected landscapes are prime areas for the Government to actively deliver on its promise. Yet the IUCN can find "no evidence" that the designations are effective for nature recovery. If we cannot protect and restore nature in our national parks, then our hope of doing so outside of them is practically non-existent.

So, what can be done?

First and foremost, the muddled approach to their role must be solved by giving all protected landscapes the overriding purpose of delivering nature’s recovery. This nature-positive approach will align with what most British people think they should be for and help shift our national parks from being largely unproductive landscapes to places where nature thrives. It would also deliver a multitude of knock-on benefits including tourism opportunities, new jobs and nature-friendly farming.

We know this works because there are already growing numbers of experienced farmers, landowners and conservationists pioneering a different approach in our national parks.

Wild Ennerdale, a rewilding project in the Lake District National Park, celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. Since 2003, it has applied rewilding principles – allowing the landscape to evolve naturally – within the valley which had suffered from loss of habitat and biodiversity. Measures such as planting native trees, re-wiggling the river and introducing conservation grazers have transformed the biodiversity of the area. Bird species have increased by almost 20%, including the welcome return of the green woodpecker. The marsh fritillary butterfly, extinct in west Cumbria, has also returned; and wild juniper, reduced to 10 bushes in 2003, has increased by 10,000%. Last November, 70% of the area was designated a “super national nature reserve”.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

Rewilding Britain – a charity that aims to "tackle the climate emergency and extinction crisis, reconnect people with the natural world and to help communities thrive" – wants to see what is being achieved at Wild Ennerdale in all our national parks and, indeed, across 30% of Britain by 2030.

We want a richer, wilder, Britain full of the abundance of life where landscape-scale restoration of natural processes, habitats and species and sustainable, nature-led farming, forestry and leisure work hand-in-hand to benefit us all.

We want to see an inspiring, diverse mosaic of rewilding where nature comes first while delivering major benefits for communities – including opportunities for vibrant green economies, healthier air, water and soils, and improved health and wellbeing.

It’s not too late, but we need to act now.

People are at the heart of our national parks. Unlike the vast wildernesses of Yellowstone or the Taiga, almost 400,000 people live and work in Britain’s national parks, many having made the land their home for generations. They must be supported to lead nature recovery and have access to the tools and resources to create their own new nature-based economies so rural communities reap the benefits of a necessary, just rural transition.

Though the IUCN’s review has confirmed that our national parks and landscapes are not effective for nature recovery right now, we know they can be in the future and we know how. This is a world we know is possible – if we only choose to make it happen.

‘Take It Down and They’ll Return’: The Stunning Revival of the Penobscot River

About a week before the removal of the Great Works Dam on the Penobscot River in Old Town, Maine, Dan Kusnierz dragged his sons to the riverside to take their picture in front of the aging structure. They had just come from a little league game. “They were being goofy and didn’t understand it,” Kusnierz, the water resources program manager for the Penobscot Indian Nation, recalls. It was 2012, and with the dam’s removal imminent, the river — New England’s second-largest — was about to transform.

For nearly two centuries, the Penobscot had been choked with logs and pulp as the timber and paper industries — both long-standing cornerstones of Maine’s economy — used it both as a lumber byway and waste receptacle. From just 1830 to 1880, more than eight billion feet of timber floated down the river. To power all this industry, dams were erected, 119 in the Penobscot River Basin alone. Two in particular, the Great Works and the Veazie, posed an outsized threat to the river’s health.

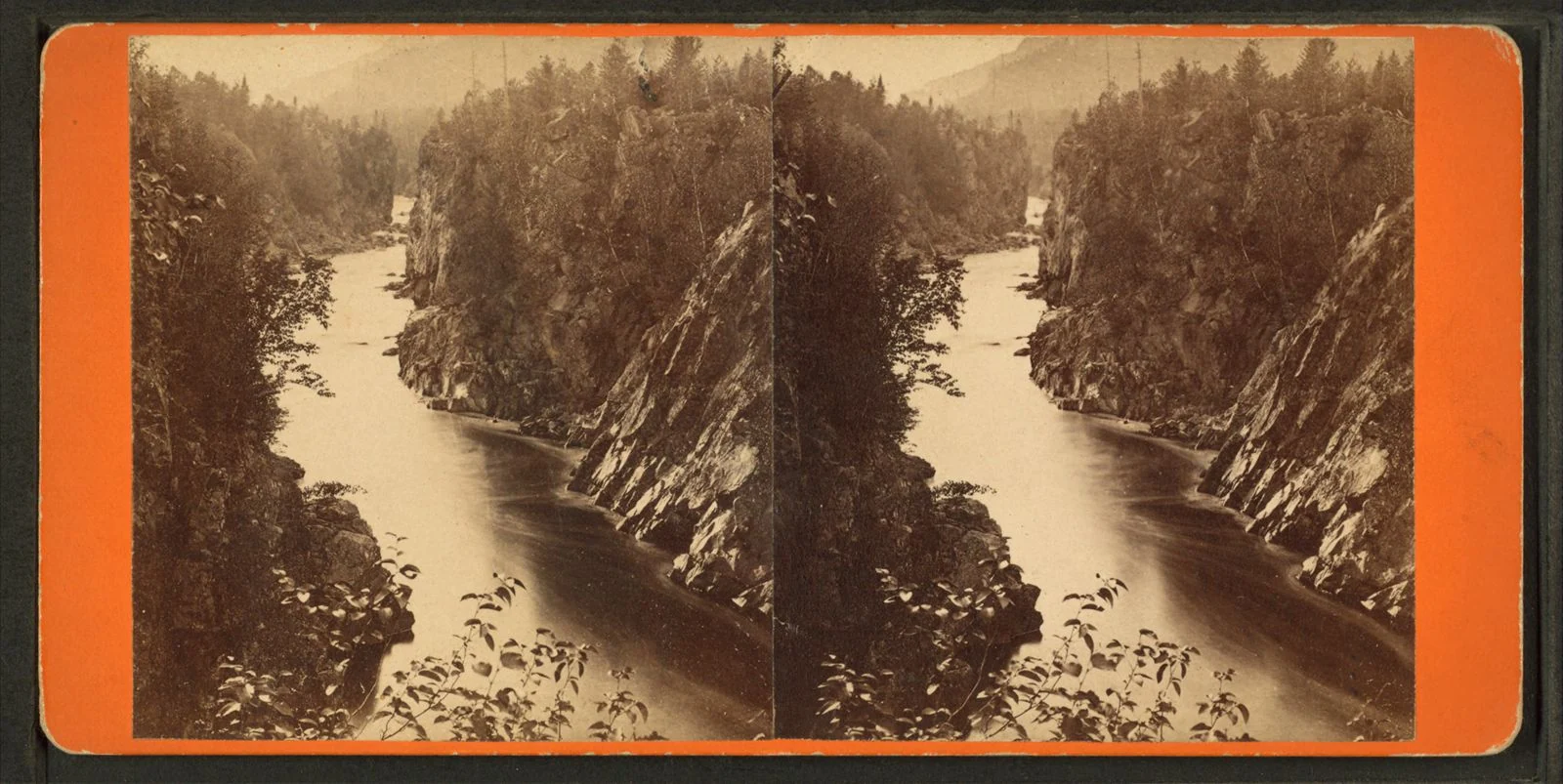

A stereograph from the 1870s shows the view from Ripogenus Falls on the Penobscot River. Credit: A.L. Hinds / Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library

A stereograph from the 1870s shows the view from Ripogenus Falls on the Penobscot River. Credit: A.L. Hinds / Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library

Perhaps irrelevant to his children posing for a picture at the time, Kusnierz, who is not Penobscot but has served the Nation for 20 years, was one the members of an unprecedented coalition of scientists, Indigenous people and conservationists working to remove both dams in order to free the Penobscot River and hopefully restore its health in the process.

The river had been sick for generations. Butch Phillips, a Penobscot Nation elder, recalls growing up on Indian Island, the Penobscot tribe reservation located near Old Town on the river, in the 1950s. By that time, the Penobscot was unrecognizable to the body of water it had once been, with drifting logs so gridlocked at times on the eastern side of the island that the river was impassable for boats and people alike. This posed an ongoing dilemma for the Penobscot people who, prior to the construction of a bridge in 1950, used canoes to travel to and from the mainland.

The Veazie Dam before removal. Credit: Joshua Royte / The Nature Conservancy

The Veazie Dam before removal. Credit: Joshua Royte / The Nature Conservancy

Despite the discharge coming from the mills, the river was still central to the Penobscot Nation’s everyday life. “[The river] was our playground,” Phillips says. “We were either canoeing on it, fishing, swimming in it and in the wintertime we were skating on it.” But the relationship had been affected. Living so closely with a body of water like the Penobscot for so many generations, he explains, “you develop a river culture. We are river people, we’re canoe people. And when you take away that element, that river and the use of the river, then you take away the culture as well.”

One of the worst blows to the river, though, was to its 12 species of sea-run fish. The Great Works, Veazie and Howland dams, all built in the 19th century, severed access to the river’s headwaters, which fish like alewives and shad, shortnose sturgeon and Atlantic salmon used as spawning ground. When the dams were erected, the effects on the fish population were almost immediate: By the 1850s, salmon no longer inhabited most of the rivers in southern Maine and their populations continued to decline so dramatically that in 1889, the US government opened the Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery in Orland, Maine to support the besieged fish. For the next 50 years, it was the primary source of salmon eggs for the region.

Credit: Kea Krause

The Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery has been raising Atlantic salmon, an iconic species of the northeastern US, since the late 19th century.

Yet salmon numbers continued to decline. By 1948, the final year of the commercial fishing industry for wild Atlantic salmon, only 40 were reported caught in the Penobscot watershed. In the late 1980s, around 2,000 salmon made it to the Veazie Dam (the first dam fish returning from the ocean encounter on the river), a number drastically whittled down from the species’ original population of about 200,000 annually. In 2009, wild Atlantic salmon were added to the endangered species list.

These were the stakes when the dams’ licenses were up for renewal in 1998, and leaders of the Penobscot Nation saw an opportunity to make a significant change to the status quo. The tribe’s plan was to purchase the dams — and then destroy them. So they joined with the Atlantic Salmon Federation to open a dialogue with the dam owner, a company called PPL Maine, to buy them. The cohort gathered more participants — American Rivers, the Natural Resources Council of Maine and Trout Unlimited — and formed an alliance called the Penobscot River Restoration Trust.

Alewives spend most of their lives at sea but rely on Maine’s inland waters for spawning habitat. Credit: Bridget Edmond / The Nature Conservancy

Alewives spend most of their lives at sea but rely on Maine’s inland waters for spawning habitat. Credit: Bridget Edmond / The Nature Conservancy

The river was in crisis: In addition to the dwindling salmon population, only two alewives were counted at the Veazie Dam in 2010 (NOAA estimates historically the river had 14 to 20 million), arguably one of its most alarming health indicators yet. Alewives, a type of river herring native to the Penobscot, feed just about everything and everyone, from the bottom of the food chain up. With no alewives, there would be no otter or fishers or osprey or eagles.

“The impacts of a dam are especially local,” says Laura Rose Day, executive director of the Penobscot River Restoration Trust. So while the Trust engaged in years-long negotiations with PPL, community outreach became an equally key component to the project’s success. Rose Day, along with Cheryl Daigle, an outreach coordinator for the project, and Butch Phillips, who was tapped as an ambassador for the Penobscot people, set out on a lengthy effort to share the good news of the project with the community. Individually, they logged hours of knocking on doors, maintaining tables and booths at sports shows, hosting the Penobscot River Revival Festival and just persistently showing up for people who came to them with questions and concerns.

The Great Works Dam mid-removal. Courtesy of the Natural Resources Council of Maine

The Great Works Dam mid-removal. Courtesy of the Natural Resources Council of Maine

It wasn’t always easy to find receptive minds. “In the broadest sense, change is an obstacle,” Molly Payne Wynne, the project’s monitoring coordinator and project associate, explains. “You’re essentially coming into a community, and you’re asking that the one thing that they see every day, or the one constant that they know — this structure in the river — you want to remove that and totally change the visual and what that means for them.”

“The key to all of these projects is finding the right equation to meet public and business and Indigenous and other rights and interests and needs, based on the place,” Rose Day reflects. Daigle says she often found herself translating the science of the project for people and also managing the varying perspectives of how a river should be: “Part of it is not being afraid to venture into that territory where there’s conflicting views about use of a resource.”

Credit: Stephen G. Page / Shutterstock

“We are river people, we’re canoe people. And when you take away that element, then you take away the culture as well.” –Butch Phillips

For his part, Phillips discovered that there was a dearth of knowledge community-wide when it came to the tribe’s relationship to the river. “My ancestors have been on this river for literally thousands of years,” he notes. “And that connection goes really deep because through those many, many generations, the people depended on the river and the surrounding land for their everyday living: Their food, their shelter, their weapons, their transportation, clothing, everything came from the river and the land.”

Phillips felt it was crucial to add that perspective to the project. “I was talking about the connection of Penobscot to the river and the fish and all the creatures, and to many of those listening, it was the first time they heard it,” he says.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Daigle’s experience reflected a similar revelation: that communicating the science was important but, perhaps, what mattered more were small moments of communion that involved the river itself. After the dams were purchased, as some of their impoundments were being let out, there was an effort to move the river’s freshwater mussels to safety. For several weeks, Daigle, along with close to seventy volunteers, waded through the waters of Penobscot, moving the mollusks out of harm’s way. “It was sort of this intimate act to move these mussels, and build a little sense of community around that,” Daigle recalls.

The project was unprecedented in its ambition and its success. The Trust ultimately raised $60 million to purchase the Veazie, Great Works and Howland dams in 2008. In 2012, the Great Works Dam was the first to go, followed by the Veazie in 2013. The Trust was unable to convince the community of Howland to remove its dam, and so a compromise was reached in which a fish bypass was added to the dam to allow an open route for returning fish. As a result, nearly 2,000 miles of habitat was opened for salmon and other species.

The Howland Dam bypass enables fish to pass safely through. Credit: Brandon Kulik / Kleinschmidt

The Howland Dam bypass enables fish to pass safely through. Credit: Brandon Kulik / Kleinschmidt

In the nine years it took to come to an agreement with PPL, which included generating more power at alternate dams so there wouldn’t be a decrease in hydroelectricity, scientists were able to seize the opportunity to really study the river, and what happens to one before and after a dam removal.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

When you dam a river, it’s like flooding a house. Water pools and settles, as does sediment, and what you get is a warm, still environment, nothing like the lively, textured existence of a flowing river. But when you remove a dam, the river’s rebound is robust and swift. In 2018, just six years after the removal of the first dam, more than two million river herring (which includes alewives) were counted passing through a local fish lift in addition to 772 salmon. “When we do on-the-ground restoration actions with these fish, they respond immediately,” says Payne Wynne. “It’s fascinating. And it’s unique in the restoration world, because in other spheres of restoration, it can take decades to see any real response to the actual, immediate restoration activity.”

The breaching of the Veazie Dam in 2013. Courtesy of the Natural Resources Council of Maine

Though the agreement and planning took several years, when the Great Works and Veazie dams were finally demolished, the river’s recovery was dramatic and swift.

The degree of the project’s success — the river’s surprising return — has bolstered hope that future efforts like it will only continue to improve the outlook for Atlantic salmon and other fish species. Though the Trust has since dissolved, work continues to remove dams further upstream along the Penobscot’s many tributaries, which would open up more cold-water spawning habitat to all the sea-run fish. But as the nearly 15-year effort of the Trust demonstrates, dam removals are arduous, persisting battles. A win is not to be taken for granted.

In contrast to the river herring, the salmon population’s recovery has been more modest, with around 1,500 returning to the Penobscot this year — the most since 2011 but still just a slight 10-year increase. “It’s a really hostile environment for Atlantic salmon in the North Atlantic right now,” says Rory Saunders, NOAA Fisheries’ Downeast coastal salmon recovery coordinator, referring to the challenges posed by climate change. “The Penobscot run in particular is almost entirely dependent on the hatchery at this point.”

A pregnant salmon at the hatchery is held up for inspection. Credit: Kea Krause

A pregnant salmon at the hatchery is held up for inspection. Credit: Kea Krause

At the hatchery this fall, 250 mature females prepared to spawn, their dappled bodies taut with eggs. The fish had migrated to the likes of Newfoundland and back, and now they swam lazily in their tank, a sign of late pregnancy. I stood in the tank observing the Fish and Wildlife techs as they scooped each female gently up in a net — taking hold of her tail and lifting her delicately, always supporting her head — for the inspection of a biologist.

The fish weren’t quite ready to spawn, but they were getting there, and learning this distinction took years of experience, of plucking expectant females from tanks and pinching their bellies, of discerning the difference between the feeling of a ziplock baggy full with water and one that’s bursting. These fish would need another week. Then the techs would do it all again—scoop, pluck, pinch.

Once the females spawned, the eggs would be fertilized and incubated, and eventually some would be placed in man-made salmon redds, tiny depressions made in the sand normally by the wiggle and swoop a female’s body, through a hole drilled in ice. This is the ritual—tender and technical—of saving the last wild Atlantic salmon on the planet.

“The Penobscot project is a tremendous first step, but it’s not a silver bullet. We need to continue to think about upstream habitat,” acknowledges Saunders. There are hopes to remove more dams along the Piscataquis River, a tributary to the Penobscot, which would allow for access to more good, cold water for the salmon, but this could take years.

Still, there is much to celebrate. “We went from 2,000 animals to five million animals in the span of 12 years. That’s as good-news-story as you see in ecology, as you see in natural resources,” says Saunders. The return of the salmon holds significance to the Penobscot Nation as well. “It’s not just the fish,” explains Kusnierz. “It’s restoring a huge part of the culture of the tribe. Those are their relatives that have long been gone and are here again. That’s what the vision of the tribe was in those negotiations. [It] was kind of the opposite of ‘build it, and they will come.’ It was ‘take it down and they’ll return.’”

Butch Phillips and Barry Dana of the Penobscot Nation offer a blessing at an event celebrating the Great Works Dam’s removal. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service

Butch Phillips and Barry Dana of the Penobscot Nation offer a blessing at an event celebrating the Great Works Dam’s removal. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service

In the tradition of the Penobscot Nation, Phillips has collaborated on the construction of two different birch bark canoes and in one instance, took the boat up the Penobscot toward Mount Katahdin, toward the headwaters. Phillips, along with other community members including one of his sons, was retracing the path of generations before him — up the river and toward the mountain, which never seemed to disappear from view despite the constant bend and curve in the water’s trajectory.

At one point, after a particularly tough paddle through an ancient waterway on the west side of the river, Phillips turned to his son. “I told him, Let’s stop, and we laid on the ground,” he recalls. The moment was one of providence: “We’re walking in the same footsteps as our ancestors have for thousands of years.” This was in 2002, prior to the removal of the dams, and the group had to maneuver the canoe around them on their journey. The restoration project was in its nascent stages then, and the hope to someday see the river healthy and unrestricted still seemed like a moon shot, even to Phillips.

“I’m just so happy that I lived long enough to see at least a portion of our river free-flowing, so that the sea-run fish can ascend the river and go to their ancestral spawning ground as they did before the dams went up,” says Phillips. “As my ancestors witnessed.”

The post ‘Take It Down and They’ll Return’: The Stunning Revival of the Penobscot River appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Nature, Wild Girls, and Putting History in a New Environmental Perspective

In her latest book, Wild Girls, Harvard historian Tiya Miles is particularly concerned with how the relationship with nature established by several nineteenth-century women—some prominent, some not—helped them flourish outside of conventional gender roles. ...

Generating Life on the Baja Peninsula, One Mangrove at a Time

This story was originally published by Hakai Magazine.

The sun sits low in the sky as David Borbón walks from one young mangrove to another, treading carefully so as not to disturb their roots. A golden glow lights the plants as he delicately checks for flowers and new growth, removing strands of dried algae and seagrass that accumulate on the saplings with the coming and going of tides. Every so often, he lets out a joyful cry upon finding a new propagule — a small, green bean–shaped seedling — growing on a tree he has planted: “My grandchild!” He takes out his phone to capture a picture of the new family member. It has taken him over a decade to get to this moment — a shoreline filled with thriving mangroves where before there was only sand — his devotion to his work unwavering.

Back in his boat, we slowly navigate the narrow channels from Borbón’s mangroves to his nearby home in the small fishing community of Campo Delgadito, mindful of our course with the dropping tide. Shorebirds scurry on the exposed mudflats, digging for their next meal. Situated on the Pacific coast about halfway down the peninsula of Baja California, Mexico, El Delgadito — “the little narrow one” — is a long spit of land jutting northwest into the mouth of Laguna San Ignacio. It’s home to 54 permanent residents, with up to 85 inhabitants during the most important fishing seasons.

White pelicans rest on a sandbar exposed at low tide. Behind them, scores of shorebirds forage for food. Over 200 bird species have been identified in Laguna San Ignacio, representing almost half of all the species found in the state of Baja California Sur, Mexico. The mangroves serve as excellent resting places and feeding grounds for many of these species. Credit: Gemina Garland-Lewis

White pelicans rest on a sandbar exposed at low tide. Behind them, scores of shorebirds forage for food. Over 200 bird species have been identified in Laguna San Ignacio, representing almost half of all the species found in the state of Baja California Sur, Mexico. The mangroves serve as excellent resting places and feeding grounds for many of these species. Credit: Gemina Garland-Lewis

To the left of Campo Delgadito, Mexico, lies the Pacific Ocean and many of the small islets where David Borbón focuses his work. On its right, mangroves grow right up and into residents’ backyards. The community is located at the southern entrance of Laguna San Ignacio, part of the Whale Sanctuary of El Vizcaíno. The sanctuary is an important site for gray whales during their birthing and breeding season and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Credit: Gemina Garland-Lewis

To the left of Campo Delgadito, Mexico, lies the Pacific Ocean and many of the small islets where David Borbón focuses his work. On its right, mangroves grow right up and into residents’ backyards. The community is located at the southern entrance of Laguna San Ignacio, part of the Whale Sanctuary of El Vizcaíno. The sanctuary is an important site for gray whales during their birthing and breeding season and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Credit: Gemina Garland-Lewis

Borbón first arrived in El Delgadito as a young man in 1980, and he returned seasonally for the fishing — lobster, sea bass, halibut and clams. “[Back then], mangroves were just branches that were in the way of navigating to go fishing. I didn’t have the slightest idea of their importance,” he recalls. By the time he permanently settled in the community in the early 2000s, he was hearing stories of overfishing, even in this remote area. Fishermen boated farther, used more gear and more gas, yet still came back with smaller catches and smaller fish. Borbón and his wife, Ana María Peralta, could see the changes but weren’t sure what to do. A conversation with their daughter, who was away at university, gave them insight into their next steps. She told them what she had been learning about mangroves: how they prevented coastal erosion, stored carbon and provided a nursery habitat for myriad fish and crustacean species, many the same as those Borbón and other fishermen in El Delgadito were catching. The trees he had barely paid any attention to became the sole focus of his attention.

Gemima Garland-Lewis

Tens of thousands of shells of callo de hacha, the pen shell clam, are piled deep surrounding the dump in Laguna San Ignacio. This species is one of several clams that form an important part of the income in this area. Many in El Delgadito, as the community is known by those who live there, believe that their children will not be able to make a living fishing as they have done. “We are taking and not putting back,” says one of El Delgadito’s fishermen.

Four species of mangroves — red, white, black and sweet — grow throughout the state of Baja California Sur, which covers the lower half of the Baja California peninsula, and elsewhere in tropical and subtropical latitudes around the world. Mangroves are perhaps not what jumps to mind in desert ecosystems like that of El Delgadito, however, which sits less than one-half of one degree south of all mangroves’ northern limit in the entire eastern Pacific. Mangroves here grow short and stunted compared with their tropical counterparts — even when fully developed, a species that reaches over 25 meters in height in the tropics may barely make two meters in this region. Their small stature doesn’t make them any less mighty from the standpoint of the ecological services they provide. Studies in Baja California Sur and the adjacent Gulf of California have shown that not only do fisheries landings increase in areas where there are more abundant mangroves but also that these mangroves match or even outperform tropical mangrove ecosystems in their carbon sequestration abilities.

Borbón stops to clean debris off some of the oldest mangroves in the area, estimated to be around 250 years old. Shortly after learning about mangroves from his daughter, a serendipitous visit from a researcher doing her thesis project on the vulnerability and resilience of the mangroves on Baja California’s Pacific coast provided him an opportunity to understand more about the life cycles of the different mangrove species and the threats they are facing. When people in his community told him he was crazy for starting to plant mangroves, she offered encouragement. To this day, he still keeps a copy of her thesis in his home. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Borbón stops to clean debris off some of the oldest mangroves in the area, estimated to be around 250 years old. Shortly after learning about mangroves from his daughter, a serendipitous visit from a researcher doing her thesis project on the vulnerability and resilience of the mangroves on Baja California’s Pacific coast provided him an opportunity to understand more about the life cycles of the different mangrove species and the threats they are facing. When people in his community told him he was crazy for starting to plant mangroves, she offered encouragement. To this day, he still keeps a copy of her thesis in his home. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

The “prop” roots of the red mangrove. Studies show that Baja California Sur’s desert mangroves grow on top of their own root remains, forming a type of peat that serves as a highly efficient environment for carbon sequestration. This peat extends to depths of more than three meters, and core samples indicate that, in some areas, it has been storing carbon at the same rate for over 5,000 years. It has also historically provided mangrove ecosystems in this region with a mechanism for keeping pace with sea level rise. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

The “prop” roots of the red mangrove. Studies show that Baja California Sur’s desert mangroves grow on top of their own root remains, forming a type of peat that serves as a highly efficient environment for carbon sequestration. This peat extends to depths of more than three meters, and core samples indicate that, in some areas, it has been storing carbon at the same rate for over 5,000 years. It has also historically provided mangrove ecosystems in this region with a mechanism for keeping pace with sea level rise. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Baja California Sur is the least densely populated state in all of Mexico, and extreme loss of mangroves is concentrated in the urban spaces of La Paz and Los Cabos. Construction of fishing camps around El Delgadito in the 1980s led to the removal of some of the area’s mangroves, but nothing has done as much damage in recent years as climate change, says Borbón. Higher tides and stronger currents undercut the sandbars that support the mangroves, carving underwater caves that eventually cause the entire root system to collapse, especially among younger trees.

Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Mature mangroves in this desert ecosystem barely stand out in the background, size-wise. El Delgadito sits less than one half of one degree south of all mangroves’ northern limit in the entire eastern Pacific, making even these centuries-old trees look short and stunted. Although mangroves make up less than one percent of the terrestrial area of the Baja California peninsula, they store about 28 percent of the total below-ground carbon in this arid climate. This makes them by far the biggest carbon sink in the region, a feature that Borbón and his wife, Ana María Peralta, know will be monumental in tackling the local impacts of climate change.

Rising sea temperatures trigger mass die-offs of seagrasses, which are swept by the currents onto mangroves, often smothering them or ripping their young roots from the substrate. Borbón painstakingly removes these deposits both from trees he has planted and from those that have grown naturally. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Rising sea temperatures trigger mass die-offs of seagrasses, which are swept by the currents onto mangroves, often smothering them or ripping their young roots from the substrate. Borbón painstakingly removes these deposits both from trees he has planted and from those that have grown naturally. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Though never formally trained in the sciences, Borbón has an incredible aptitude and devotion toward experimentation. Taking what he knew from being raised in an agricultural region of Mexico, he carried out early iterations of his work growing mangroves in a greenhouse. He soon found that the young trees couldn’t handle the shock of being transplanted, so he and Peralta started “playing scientists,” as he calls it, planting propagules in the places surrounding El Delgadito where they ultimately wanted them to grow. Over the years, they have perfected the process to a point where they may very well know more than anyone else about growing mangroves in this desert ecosystem, though they never stop experimenting with new ideas.

Borbón checks on some of his two-year-old trees. When he first started, he’d experiment with spacing between the plants as well as their distance from the high tideline. He also tested how wind, current, waves, and cardinal direction to these natural forces changed his success. “Do you know what the most important thing is?” he asks me. “Not science, not technology. Heart.” Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Borbón checks on some of his two-year-old trees. When he first started, he’d experiment with spacing between the plants as well as their distance from the high tideline. He also tested how wind, current, waves, and cardinal direction to these natural forces changed his success. “Do you know what the most important thing is?” he asks me. “Not science, not technology. Heart.” Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Peralta and Borbón with the mangroves across the dirt road from their home. In recent months, Borbón has been invited to present at international conferences, heard pitches from the World Bank, and been asked to begin a train-the-trainers program for others trying to restore mangroves in their communities. “We are not talking about sustainability,” he says, “we are talking about regeneration — and it’s worth fighting for, whatever is required, because it’s necessary. It’s very necessary in these communities to avoid emigration, to create opportunities for both young and old, for men and women, for people on the coast and people on ranches in the sierras [mountain ranges], because this is wonderful.” Credit: Gemima Garland-LewisToday, Borbón and Peralta have a team of over 20. It is paid work—the only of its kind in this area that isn’t from fishing. Funding now comes from partnership with a US-based environmental services company instead of from the couple’s own pocket. Their team members range in age from 19 to 60, though the majority are youth. “Our focus is more with the younger than the older generations,” explains Peralta. “You can’t change what they’re accustomed to. But the young people are learning. They’re the future of here, the future of Mexico, the future of everything, to continue with the mangroves.”

Peralta and Borbón with the mangroves across the dirt road from their home. In recent months, Borbón has been invited to present at international conferences, heard pitches from the World Bank, and been asked to begin a train-the-trainers program for others trying to restore mangroves in their communities. “We are not talking about sustainability,” he says, “we are talking about regeneration — and it’s worth fighting for, whatever is required, because it’s necessary. It’s very necessary in these communities to avoid emigration, to create opportunities for both young and old, for men and women, for people on the coast and people on ranches in the sierras [mountain ranges], because this is wonderful.” Credit: Gemima Garland-LewisToday, Borbón and Peralta have a team of over 20. It is paid work—the only of its kind in this area that isn’t from fishing. Funding now comes from partnership with a US-based environmental services company instead of from the couple’s own pocket. Their team members range in age from 19 to 60, though the majority are youth. “Our focus is more with the younger than the older generations,” explains Peralta. “You can’t change what they’re accustomed to. But the young people are learning. They’re the future of here, the future of Mexico, the future of everything, to continue with the mangroves.”

Borbón helps Victoria, one of his core team members, transplant a year-old mangrove. He is worried he planted last year’s trees too close together and is experimenting with moving them farther apart while they are still young. These year’s propagules will be placed farther apart from the get-go. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Borbón helps Victoria, one of his core team members, transplant a year-old mangrove. He is worried he planted last year’s trees too close together and is experimenting with moving them farther apart while they are still young. These year’s propagules will be placed farther apart from the get-go. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Borbón and Peralta soak the propagules for eight to 11 days in fresh water to stimulate the growth of root nodules. Then, with their team of young community members, they count the propagules and place them in buckets to take into the field, doing quality control along the way. Borbón has learned over the years that it’s best to target those that have developed to the point where they are still attached to the parent tree but fall off easily, like ripe fruit.

During the summer months, they take scouting trips to monitor the development of new red mangrove propagules and tend young trees. Come October, they harvest the propagules and soak them in fresh water for just over a week. At the restoration site, one person walks a transect line using a wooden tool to punch a small hole into the sediment while another follows with the propagules. It takes just a second to plant each one, and over the past 12 years they’ve planted an estimated 1.2 million and watched stretches of bare sand transform to green. It’s still too soon to see the impact on local fisheries, but Borbón has no shortage of hope: “The fact that we plant mangroves generates life. We expand the possibilities of helping nature by allowing them to naturally repopulate and recover.” He adds that the “constant attack” from fishing limits recovery, but he’s not deterred. “That is why it is so important that we continue with our efforts.”

Working as a team, community members of El Delgadito plant new red mangrove propagules alongside one-year-old trees from last season’s work. Borbón and Peralta have found that, aside from the direct investment in mangroves, hiring youth also takes away some of the impact of local fisheries by providing people with an economic alternative. “We need jobs for young people. Because many can’t get an education, and they get married very young and want to do the same as their parents, they become fishermen and fish as much as they can. They need jobs, another type of work,” Peralta explains. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Working as a team, community members of El Delgadito plant new red mangrove propagules alongside one-year-old trees from last season’s work. Borbón and Peralta have found that, aside from the direct investment in mangroves, hiring youth also takes away some of the impact of local fisheries by providing people with an economic alternative. “We need jobs for young people. Because many can’t get an education, and they get married very young and want to do the same as their parents, they become fishermen and fish as much as they can. They need jobs, another type of work,” Peralta explains. Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Credit: Gemima Garland-Lewis

Areas that started as bare sand quickly developed vegetation once the young red mangroves stabilized the soil. Species like Salicornia and white mangroves sprout on their own, forming a cover of green.

In early September 2022, Hurricane Kay made landfall several hours north of El Delgadito. Colder surface waters on the Pacific coast of Baja California have historically made it rare for a storm system to make its way this far north along the peninsula. Mangroves have been shown to absorb 70 to 90 percent of a wave’s energy, and the storm put Borbón and Peralta’s work to the test. Areas that had their first mangroves planted 10 years prior were destroyed, leaving almost nothing but sand where the highest branches once reached overhead. The couple was devastated, and Borbón’s eyes filled with tears when he broke the news to me. He estimates that, in addition to those first trees he planted, close to 300,000 young trees were lost. Soon after, a marine biologist friend brought an impact assessment expert from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to see El Delgadito. She looked at the proximity of the mangroves that had been destroyed to the community and told the couple that their work very likely prevented the loss of much of their community.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

The researcher’s comments provided hope for the future and validation to Borbón and Peralta that their efforts weren’t for naught. Today, looking out from the driver’s seat in his small boat, Borbón envisions what is to come. “My dream for this region has no limits; what can be done is wonderful. We have dedicated ourselves to conservation because it is very clear to me that the day mangroves end, life ends in this region.” Tomorrow, he’ll wake at dawn and drink a cup of coffee before driving down the road to his boat, never missing a beat in his dedication to making his vision a reality.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The post Generating Life on the Baja Peninsula, One Mangrove at a Time appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The Legendary Ocean Explorer Protecting ‘Hope Spots’ Around the World

Despite celebrating her 88th birthday last August, Sylvia Earle seems to whirl around the globe faster than a hurricane gathering strength. She still travels about 300 days of the year and just returned from the Cayman Islands, Brazil, Mozambique, Mexico, Antarctica and Europe. “I feel like an octopus with all arms fully engaged,” she says about her workload. “If a child is about to fall off a 10-story building and you are in a position to catch it, you’ll do everything in your power to be positioned just so you can save it. You don’t look away and have a cup of tea in the meantime.”

Earle’s sense of urgency is due to her unique position in history. The first woman to dive with scuba gear in the early 1950s, the first person to walk on the ocean floor 1250 feet under the surface in 1979, the first female chief scientist of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1990, she has explored the oceans deeper and longer than any other woman on the planet. This gave her a front-row seat to the changes occurring below the surface, long before women were welcomed in marine sciences.

Now, when she returns to spots that once brimmed with fish and vibrant corals, she often only finds a gray underwater desert. While about 12 percent of the land around the world is under some form of protection, less than three percent of the ocean is protected.

Earle diving in the Galapagos. Credit: Carl Lundin / Mission Blue

Earle diving in the Galapagos. Credit: Carl Lundin / Mission Blue

“Which means 97 percent are open for exploitation,” she says. “We have lost about 90 percent of sharks, tuna, and other fish, and 50 percent of coral.” “Her Deepness,” as the world’s most renowned marine scientist is lovingly called by friends and fans, has been working to change that. In 2009, she started the nonprofit Mission Blue with 19 Hope Spots, defined as “areas critical to ocean health in that they have a significant amount of biodiversity.”

There are now 158 Hope Spots, “and counting,” Shannon Rake, Mission Blue’s Hope Spot Manager, emphasizes. Hope Spots can be as large as the coral triangle in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Sea and as well-known as the Galapagos Islands, or small and quite unknown, like a dozen seamounts off California’s coast. No matter how tiny, Earle is convinced every Spot counts. “Every place, even the small places, makes a difference,“ she insists. “But we need to scale up. We need to get big. Take care of the ocean as if your life depends on it because it does.”

The Harvard-trained marine scientist with a PhD from Duke University has made it her mission to advocate for the ocean. Earle compares the ocean to our heart. “You wouldn’t say you need to protect just three percent or even 30 percent of your heart,” she says. “The oceans are the heart of the planet. Without it, life is not possible.”

Initially, Hope Spots were identified by renowned scientists. But after the 2014 Netflix documentary Mission Blue made her idea popular and people started reaching out to the nonprofit, Earle opened the process up to the public. “We’re overwhelmed by nominations from the public,” Rake admits before she adds, “in a good way!” She receives up to 100 nomination requests per year that are reviewed by a committee.

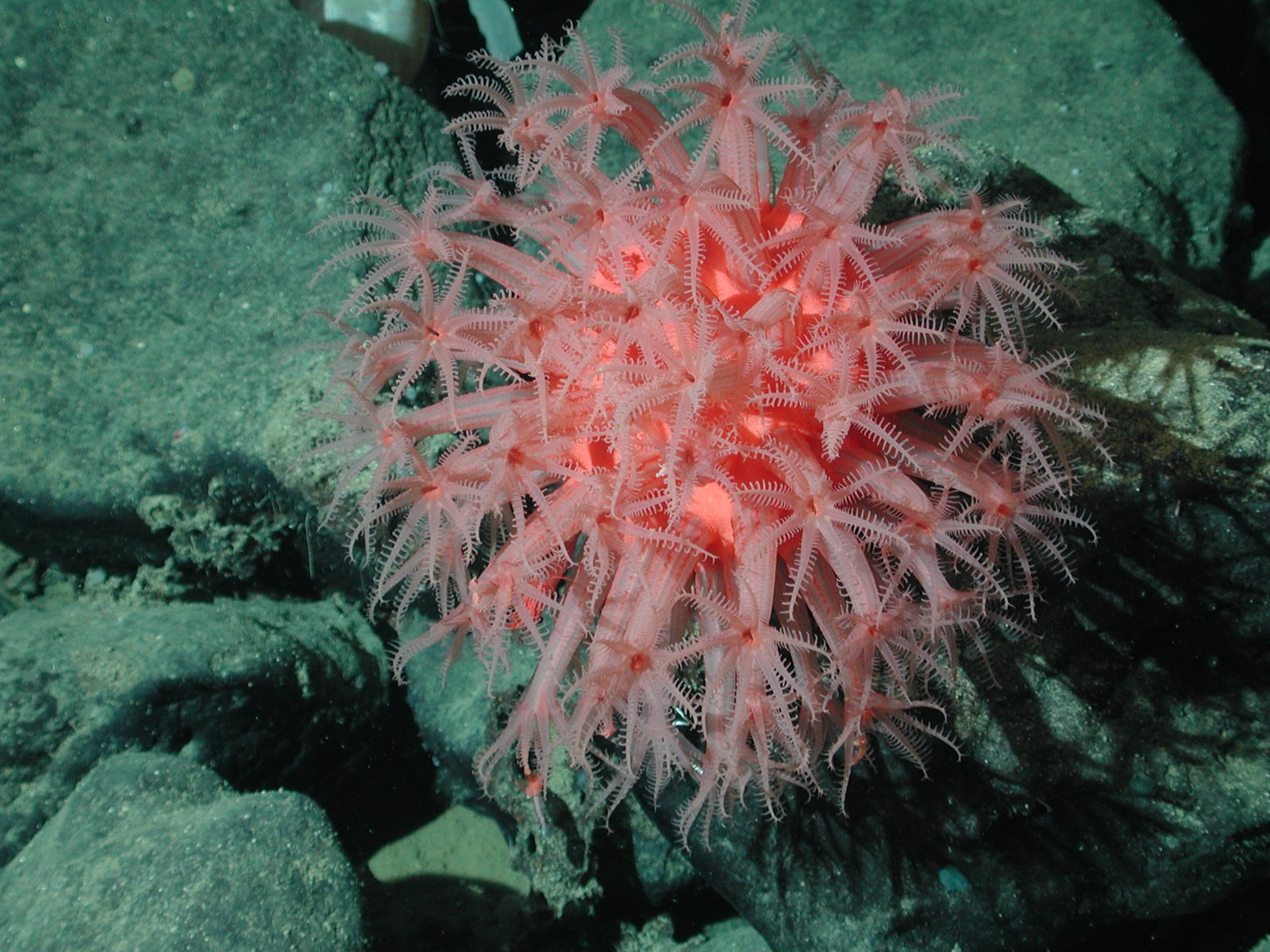

A mushroom coral at Davidson Seamount, California. Credit: NOAA / Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

A mushroom coral at Davidson Seamount, California. Credit: NOAA / Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

While Earle is petite in stature, she maintains a vigorous and outsized optimism. “I think you could get really depressed looking at headlines if you wished to focus on the bad news; there’s plenty of it,” she admits. “If we wait much longer to act on those opportunities we will lose the chance. So this is literally the best time that I can think of in all of history to be alive because just in my lifetime, I’ve witnessed greater insight, greater knowledge, about the fabric of life.”

One Hope Spot is literally just outside the windows of her Alameda, CA, office — the San Francisco Bay. “Admittedly, it’s not exactly pristine,” Earle comments, “but better than it has been in the past because people are coming together to take action and restore its health.”

When she started exploring the seas decades ago, humankind thought the oceans were so vast they could handle any amount of trash, toxic pollutants and fishing boats. Earle was among the first to sound the alarm.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

She was also the one who pointed out that Google Maps should be called “Google Dirt” because it didn’t map the oceans, only the land. Google promptly expanded its program to map the blue.

Some Hope Spots are already fully protected marine areas, and the designation is meant to help keep the protections in place when governments change or funds dry up. At other times, the nomination process for a Hope Spot can help galvanize the support of local governments and environmentalists to put legal protections in place. “Mission Blue is trying to help the local communities and ocean champions to move the needle,” Rake says. “Then we’re trying to maintain that status because as we know, administrations change and can roll back policies. We’re using our collective power and community activism to let elected officials know how important this place is. No, you really shouldn’t build a timber port right here in the migratory pathway of endangered southern right whales. This allows the elected officials to learn more about what’s at stake and what the community wants.”

“I feel like an octopus with all arms fully engaged,” says Earle, who still works ambitiously at age 88. Credit: Taylor Griffith / Mission Blue

“I feel like an octopus with all arms fully engaged,” says Earle, who still works ambitiously at age 88. Credit: Taylor Griffith / Mission Blue

For instance, Cabo Pulmo in Mexico was so badly overfished that fishermen kept pulling empty nets from the sea. In the late 1990s, the fishing cooperatives joined forces with scientists, implemented fishing regulations and replaced income from fishing with ecotourism. Through Global Fishing Watch, Mission Blue observed fishing ships leaving the area after protections were put in place. “The tuna industry was very against [the no-take designation] because they thought their catch would decline but it ended up being the reverse,” Rake remembers. “They now see a 25 percent increase in their yield near the protected areas because of the spillover effect when you protect an area.”

The Palmahim Slide in Israel is another example of a Hope Spot that didn’t have any protection before it was nominated. The rare geological formation deep in the Mediterranean Sea, about 20 miles off the Coast of Tel Aviv, is a biodiversity hotspot where catsharks breed and bluefin tuna spawn. “We helped the marine conservationists with letters of support, scientific advisory and communication, and they were able to create a protected area approved by government officials,” Rake explains. “We’re using our international spotlight to really push for protection in these areas.”

“Every Hope Spot is on a different journey,” Rake says, referring to widely varying local regulations. She mentions Shinnecock Bay on Long Island’s South Shore as another example where the Hope Spot designation had a measurable impact. “It was severely degraded, was having red and brown tides,” Rake says. “There has been an absolute incredible change, doing restoration work with clams and oysters.”

Schools of rock hind and creolefish rest along the reef in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: G. P. Schmahl / Flower Garden Banks NMS

Schools of rock hind and creolefish rest along the reef in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: G. P. Schmahl / Flower Garden Banks NMS

Earle’s favorite Hope Spot might be the Gulf of Mexico. Earle was 12 when her parents moved the family from New Jersey to a beach house in Florida. The ocean became her playground. “It’s where I first took the plunge as a kid and saw what life is like underwater.” It was also in Florida that she first became aware that nature was being destroyed for human consumption.

Mission Blue cooperates with more than 200 ocean conservation groups worldwide, aiming to galvanize local, regional, national and international protection. Some are well known, such as the Ocean Elders, ambassadors for the oceans that include primatologist Jane Gooddall, filmmaker James Cameron, mogul Richard Branson and musician Neil Young. Earle speaks of “creating a network of hope. The idea is to get people who can weigh in at a level that transcends political boundaries.”

While being fully aware of the damage done, Earle keeps coming back to the positive changes. “This past year, some tangible actions have been taken that are cause for optimism,” she says, referring to the UN Ocean Treaty that aims to protect 30 percent of the oceans by 2030 and the Biodiversity Treaty. “The Biodiversity Treaty recognizes that we’re on a downhill slide to lose at least a million species by the end of this century if we keep doing what we’re doing.”

Earle acknowledges, “We are not currently behaving with that kind of intelligence. We’re using the old model of consuming nature without being concerned about the impact on the next 10 years, the next hundred years, the next thousand years.” However, she points out that the numbers of the California condor and other species, including some whales, who were on the brink of extinction have been successfully restored: “We’ve helped get them back to certainly a better place not where they were 500 years ago, but certainly better than they were 50 years ago.”

A school of blue tang swim about the reef in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: G. P. Schmahl / Flower Garden Banks NMS

A school of blue tang swim about the reef in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: G. P. Schmahl / Flower Garden Banks NMS

When people ask her what they can do to help, the mother of three and grandmother of four tells them to focus on what they love. “You know, we’re causing the problems,” she says. “So we can also cause solutions. You can make change right now, at home. You can make change every day with what you eat, what you wear, with how you vote, with what you plant in your garden if you have access to a yard, with the organizations you join. Would you like to be part of the generation that safeguards our species, safeguards the future of life on earth?”

And of course, anybody can nominate a Hope Spot.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

“We should look at this as the best time ever to do something,” Earle insists. “It’s just getting to the point where people realize the urgency. We have to change if we are to survive. It has taken us a very short period of time to begin to seriously unravel the stability of the systems that we absolutely require for our existence. Now imagine if we didn’t know that. That would be a real problem. But we do know now and we know what to do.”

Earle is relentlessly positive when it comes to the future, and the opportunity we have right now to shape it. “That is a reason to be cheerful,” she says. “We know more than ever before at any time in history, and here’s the opportunity to really size up. Where do we want to go? Because we do have choices.”

The post The Legendary Ocean Explorer Protecting ‘Hope Spots’ Around the World appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

The EU Just Banned Microplastics. How Are Companies Replacing Them?

A blue whale can ingest about 10 million pieces of microplastics per day. This alarming fact, drawn from a recent study, underlines what has become increasingly clear: Microplastics — solid plastic particles up to five millimeters in size that are not biodegradable — are pretty much everywhere.

They have been detected in over 1,500 different marine animal species. They also find their way into our bodies via the water cycle and the food chain. In fact, the average person consumes up to five grams of microplastics per week. That’s as much as a credit card. The consequences for our health and the environment remain to be seen.

In a move to stave off further damage, the European Union has now banned intentionally added microplastics. This applies to plastic glitter or polyethylene particles used as abrasives in scrubs, shower gel and toothpaste (these have been banned in the US since the 2015 Microbead-Free Waters Act). Under the terms of the ban, some products, such as plastic glitter found in creams or eye shadow, have been granted a transitional period to give manufacturers a chance to develop new designs.

In some of its products, LUSH uses salt in place of microplastics. Courtesy of LUSH

In some of its products, LUSH uses salt in place of microplastics. Courtesy of LUSH

But some manufacturers are years ahead of the game when it comes to pioneering the move away from microbeads. LUSH and The Body Shop are among the companies that have long been offering natural alternatives, using ground nuts, bamboo, sea salt and sugar. The really big players, such as Beiersdorf AG, have also been working on solutions for several years.

The Hamburg-based consumer goods group has not used microbeads for exfoliation purposes since 2015. Instead, it has used, for example, cellulose particles or shredded apricot kernels. Since the end of 2019, all Beiersdorf wash-off products have been free of microplastics. In addition, the company uses almost no microplastics in creams and other leave-on cosmetics for its two major body care brands, Nivea and Eucerin. “Our ambition is to use only biodegradable polymers in our European cosmetic product formulas by the end of 2025,” explains a company spokesperson. However, these polymers can take many months to degrade. And they may prevent the development of more sustainable solutions.

LUSH’s Bjork sugar cleanser uses sugar in place of microplastics. Courtesy of LUSH

LUSH’s Bjork sugar cleanser uses sugar in place of microplastics. Courtesy of LUSH

There have also been alternatives for artificial turf pitches — which use tons of microplastics as loose fill — for some years now. There are more than 9,500 such sports pitches in Germany alone. “These particles can quickly be carried into the environment by wind and weather or sports shoes,” says Jürgen Bertling from the German Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety and Energy Technology (Umsicht). According to the European Chemicals Agency, artificial turfs release up to 16,000 tons of microplastics into the environment in the EU every year.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

But a few years before the EU ban, Germany stopped providing public funding for artificial turf pitches with granules containing a high proportion of microplastic. As a result, the country already has hundreds of pitches that are filled with cork and sand instead of microplastics, according to the International Association for Sports and Leisure Facilities. Ground olive stones or corn-based fillings have also been used on some pitches.

One of the most sustainable facilities in Germany was completed a year ago by the Lower Saxony club VfL Sittensen. Their artificial grass is made from plant-based polyethylene. The granules are produced mostly from hemp and chalk. Compared to other artificial turf pitches, this pitch only needs a fifth of the amount of granulate. In addition, a filter system for the rainwater run-off prevents the remaining microplastic and fiber residues from entering the environment. “We receive many inquiries from other clubs and local authorities who want to follow this example,” says Egbert Haneke, the association’s chairman.

Hundreds of artificial turf pitches in Germany are filled with cork and sand instead of microplastics. Courtesy of VfL Sittensen

Hundreds of artificial turf pitches in Germany are filled with cork and sand instead of microplastics. Courtesy of VfL Sittensen

But there are other, much bigger sources of microplastics in Germany. According to a study by the Fraunhofer Institute Umsicht, artificial turf pitches are only the fifth-largest source. And though cosmetics are the one that the public tends to hear the most about, they are a relatively insignificant source compared to the heavy-hitters, like waste disposal, building materials, road wear and fibers released through textile washing.

Germans produce an estimated four kilograms of microplastics per capita in the environment every year. At around 1.2 kilograms per capita, tire abrasion is the most important contributor. Tiny particles are released through the wear and tear of tires, and counterintuitively, the move toward electric vehicles will actually exacerbate this problem. Electric cars are significantly heavier than combustion engines due to their batteries. A toxic compound released by tire abrasion has even been linked to the deaths of coho salmon on the US West Coast.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

A startup in the UK has found a possible solution: The Tyre Collective has developed a suction device that can be fitted directly behind the tires on the underbody of a car.

The patent-pending technology uses electrostatics and airflow to attract tire particles. Together with the London logistics company Zhero, The Tyre Collective tested prototypes on London’s streets for three months. According to the startup, over half of the particles that the device captured were below 0.01 millimeters in size. Particles of this size are considered “the most harmful to human health and the environment,” according to The Tyre Collective. Working with designers, the start-up has also developed various products made from tire particles and recycled plastic using 3D printers. A vase, speaker, lamp and acoustic panel were exhibited at the London Design Festival at Material Matters in September 2023.

A prototype of The Tyre Collective’s suction device. Courtesy of The Tyre Collective

A prototype of The Tyre Collective’s suction device. Courtesy of The Tyre Collective

But by far, the greatest potential for reducing microplastics lies in not producing them in the first place: for example, by driving less or slower so fewer particles are released via tire wear, or by changing the composition of the material of tires or the design of the tread. And microplastic emissions from textile washing could be reduced by using different materials and designs.

That’s why, though the ban is an important step, experts like Jürgen Bertling are hanging their hopes on the EU’s ecodesign guidelines, which will be developed for the various product groups over the coming years. Something to look forward to, for humans and blue whales alike.

The post The EU Just Banned Microplastics. How Are Companies Replacing Them? appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Anna Atkins: Botanical Illustration and Photographic Innovation

This event is supported by TORCH as part of the Humanities Cultural Programme, one of the founding stones of the future Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities. Supported by TORCH through the Humanities Cultural Programme. Join us for an online in-conversation with Prof Geoffrey Batchen and Dr Lena Fritsch, discussing the work of pioneering British photographer and botanist Anna Atkins (1799-1871). Her innovative use of new photographic technologies linked art and science, and exemplified the potential of photography in books. Geoffrey Batchen is Professor of Art History at the University of Oxford and Dr Lena Fritsch is the Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. This talk accompanies the 2020 Photo Oxford festival, Women and Photography: Ways of Seeing and Being Seen.