agriculture

Cartoon: The dirty food dilemma

Cartoon by Jen Sorensen.

This Guardian article lists various foods that tend to be high in toxic PFAS, commonly known as "forever chemicals," which are used to make products stain- and water-resistant. To quote from the report, "Among the main sources of food contamination are tainted water, greaseproof food wrappers, some plastics, pesticides, or farms where PFAS-tainted sewage sludge is spread as fertilizer." As for microplastics, where to begin? They're everywhere, from human placentas to the oceans to Mount Everest.

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

The Commons of Ameland: An Uncommon History.

There is no ‘tragedy of the Commons.’ But a tragedy of the absence of Commons-as organizations, let’s call it ‘the tragedy of uncommons’, does exist. Below, I will provide the example of the island of Ameland in the Northern Netherlands, in line with the historical examples of successful Commons mentioned by Elinor Ostrom (especially those […]

An Ancestral River Runs Through It

Jeff Wivholm isn’t partial to mountains. He likes to be able to see the weather rolling in, something remarkably possible in the northeastern corner of Montana.

On a cold January morning, Wivholm drives the dirt roads between farms in Sheridan County, where he’s lived for all his 63 years, with practiced ease, pointing out different plots of land by who owns them. And if he doesn’t know the family name, Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District or Brooke Johns with the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge — both sitting in the backseat of his truck — can supply it.

If you look to the right there, Wivholm says, you can see the valley created by the aquifer. Maybe he can, his eyes accustomed to seeing dips and crevasses in, to an unfamiliar eye, a starkly flat landscape. He laughs and says it takes some getting used to.

That aquifer isn’t unique in Montana. There are 12 principal aquifers running like underground rivers throughout the state. But the way Sheridan County uses the water is.

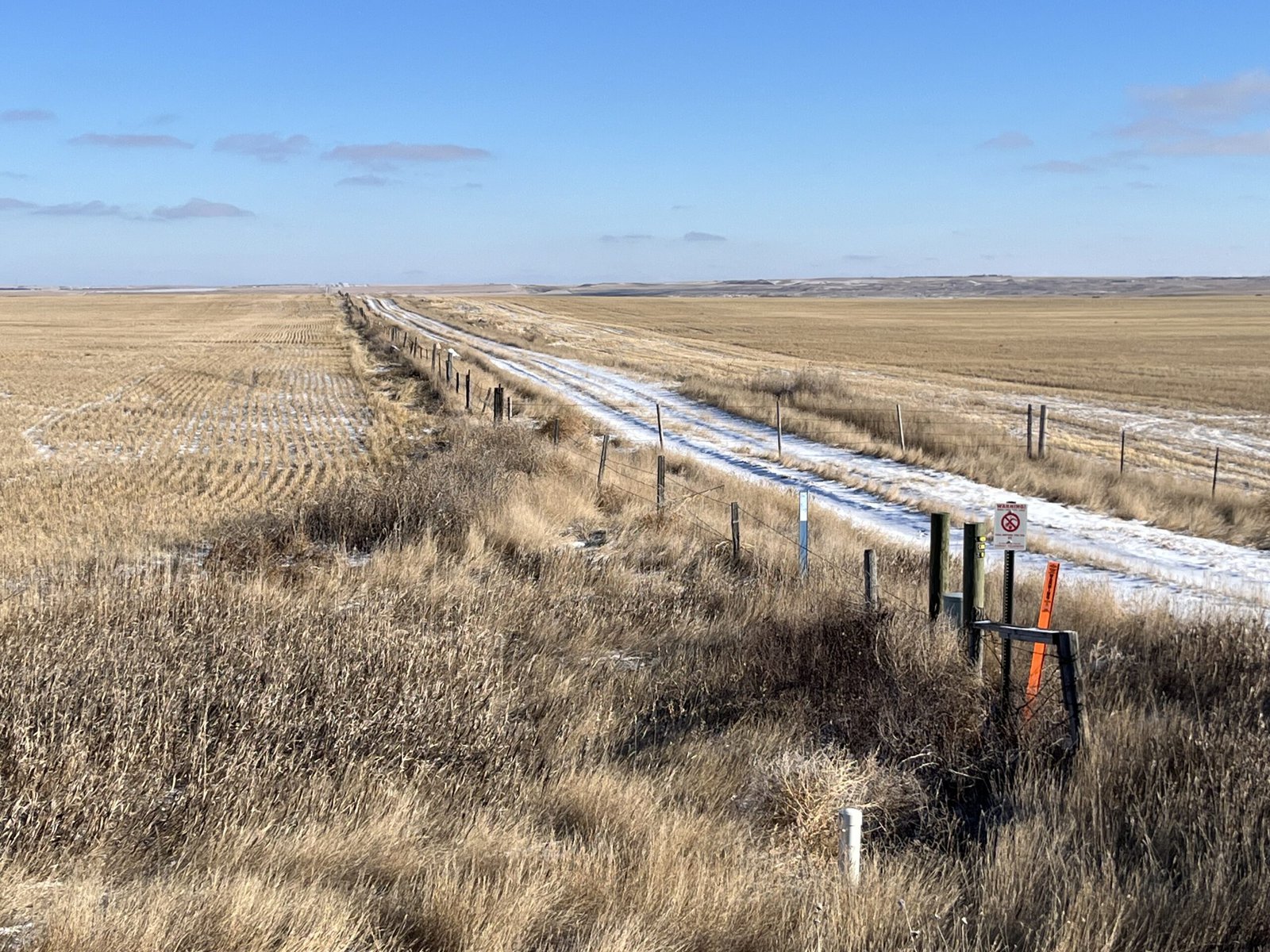

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

Montana is in relatively good shape as far as its groundwater supply goes, something uncommon across much of the country, geologist John LaFave with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology says. State politicians initiated a groundwater study over 30 years ago after years of intense drought and fires and a lack of data.

But Sheridan County was ahead of the game: The county’s conservation district started studying its groundwater in 1978, before state monitoring began.

In 1996, the district was granted a water reservation, or water allocated for future uses, from the state, which meant it could take a certain share of water from the Clear Lake Aquifer. Because of all the data it gathered through studying its groundwater, the district developed a unique way of using and distributing that water.

What’s unusual is how intentional the collaboration was and how extensive the groundwater monitoring was and continues to be. The district does this by working with farmers, tribes and the US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) to ensure water can be used by those who need it — those who would be most affected by any degradation to the water — without negatively impacting the environment.

And it’s worked. The conservation district has been using its geologically special aquifer — a gift granted to this area by the last Ice Age — to irrigate crops, provide jobs for the region and keep agriculture dollars within the community for almost 30 years while fielding few complaints.

“To me, this represents the way groundwater development should occur,” LaFave says.

Sheridan County is extremely rural, home to about 3,500 people across its 1,706 square miles. Agriculture is a big economic driver. Bird hunting is an attraction for locals and visitors. The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located in both Sheridan and Roosevelt Counties and managed by the USFWS, is home to many migratory bird species. It’s the largest pelican breeding ground in Montana and the third-largest in the country.

This early January morning, it’s about five degrees, but there isn’t a lot of snow on the ground. Over coffee and breakfast in Plentywood — the county seat — Yoder and Wivholm say this winter has been warmer and drier than usual.

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

Dry weather is not uncommon here. Droughts in the 1930s and ’80s were particularly rough. Also in the ’80s, irrigation technology was becoming more common and efficient, Wivholm says, and people began to pay more attention to the possibility of an aquifer as a way to ensure water would be available for irrigation.

“There are several nicknames for much of this property, but it was basically ‘poverty flats,’” Jon Reiten, hydrogeologist with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, says. The soil is sandy, gravelly and drought-prone. Not great for dry-land farming.

Marlowe Onstead was the first farmer in Sheridan County to use the aquifer for his pivot irrigation in 1976.

“Couldn’t raise the crop on it before,” Onstead says. After irrigation, he was able to grow alfalfa.

According to Reiten, the aquifer ranges from a mile to six miles wide and two to three hundred feet deep. The ancestral Missouri River channel, discovered in Sheridan County in 1983 as monitoring began, flowed north into Canada and east into Hudson Bay. That channel was dammed by glaciers in the last Ice Age and left behind a reservoir that was buried as glaciers melted, creating the Clear Lake Aquifer. Since the materials left behind were coarse and varied, water could move easily and be stored in great depths. A downside is that these glacial aquifers can take a long time to refill.

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

As drought dragged on in the ’80s, locals and county and state authorities set about figuring out the best way to distribute the aquifer’s water. Medicine Lake lies on top of some of the aquifer, and the Big Muddy Creek — where the Fort Peck Tribes require a minimum in-stream flow to promote ecosystem health — is at its southwestern border.

The Fort Peck Tribes and the USFWS were concerned about their respective water levels and how they’d be impacted by irrigation. Reiten says the USFWS was objecting to just about every water rights case that went to the state at the time, and all that litigation ended up in water court.

“That’s a lot to put on a producer, to have to go up against the federal government,” Reiten says.

Negotiations with the USFWS and the Fort Peck Tribes led to the formation of an advisory committee and the transfer of the water reservation on the aquifer from the state to the conservation district. (Per Montana water law, all water belongs to the state and individuals are required to get a water right to use it in a particular way — in this case, for irrigation.) Since then, Sheridan County Conservation District has had the authority to give water allocations from the Clear Lake Aquifer to producers without the producers having to appeal to the state.

The maximum amount of water that can be pulled from the aquifer is just over 15,000 acre feet total, a number set by the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Currently, the district is using about 10,000 acre feet. Increases are allowed as long as monitoring shows the aquifer isn’t being overly impacted by irrigation.

Credit: Keely Larson

The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge is home to the third largest pelican breeding ground in the country and the largest in Montana. Negotiations with the US Fish & Wildlife Service, which manages the refuge, helped Sheridan County Conservation District obtain the water reservation for the Clear Lake Aquifer.

“We were basically forced to monitor it, but it only makes good sense,” Wivholm, who has been on the conservation district board since 1994, explains. The district wouldn’t want to grant someone a right only to find out in five years that there’s not enough water.

Once a year, the committee meets to assess new water rights. The committee includes the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, the state Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, representatives from the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, county commissioners, a county planner, the Fort Peck Tribes and a representative with the United States Geological Survey.

If a farmer wants an irrigation pivot, they have to “pump it hard for 72 hours,” Wivholm says, to make sure there is enough water for their request, and understand how that pumping affects other wells nearby.

Data comes from Yoder’s efforts. She collects readings from data loggers placed in the ground throughout the county from April through October. For the first and last collections, she visits 201 wells and it takes her three 12-hour days to get to them all. Driving around in Wivholm’s truck, she points out some of her data loggers sticking up from the ground every few minutes.

Through monitoring, Sheridan County Conservation District and the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology have been able to map the entire aquifer. They take note of the water levels, monitor each irrigation pivot and can see seasonal fluctuations.

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

“It’s kind of a hidden resource, but the amount of crops that we can get off of the poor ground that is above the aquifer is amazing,” Yoder says. She lists corn, wheat, chickpeas, lentils, canola, mustard and alfalfa.

Another farmer in the area, Rodney Smith, has been irrigating from the Clear Lake Aquifer for over 35 years and has the biggest pivot connected to the aquifer.

Smith says irrigating has been economically beneficial: His farm isn’t as dependent on the weather, and it’s taken the risk out of production. Smith Farms Incorporated produces hay for livestock and sells it to other ranchers in the area. Smith also leases land out to other farmers who grow potatoes and sugar beets.

From an aerial view, his circular pivot plots show different colors of green and brown, indicating a variety of crops grown.

Smith had an early contested pivot case with the state of Montana, before the water reservation was transferred to the conservation district, which went to the state water court.

The gist of the case was that Smith Farms wanted to change their method of irrigation and the USFWS was concerned it might impact the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Data and monitoring done by the conservation district backed up Smith’s case.

“When you start irrigating, you wonder what is the capacity, or how much can you irrigate,” Smith says. “It’s always interesting to know what it’s doing.”

Credit: Google Earth

Land that is irrigated with pivot irrigation shows up in circular plots from above due to the way the structure pivots around a fixed point. Here, the circular pivot plot is sliced into different colors where different crops or phases of harvest have occurred.

Johns, with the wildlife refuge, says the refuge has a water reservation on Medicine Lake and is allowed to keep the lake filled for the protection of migratory birds. The refuge operates dams and diversions to maintain this need. Making sure any irrigation wouldn’t draw down the level of the lake has been a goal from the beginning, Johns says, and so far, that hasn’t been an issue.

There haven’t been any other contested cases on aquifer irrigation, and many, including Smith, see this as a success in having local control over a local resource.

“Water rights are such a contentious thing,” Johns notes. “And without the data, had they not started this years ago, it would be hard to start it today and get the same momentum they did.”

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Arnold Bighorn, water rights administrator for the Fort Peck Tribes, says the collaboration between all those affected by the aquifer — counties, tribes and the wildlife refuge — has worked well.

“Everybody’s on the same page, which is good,” Bighorn says.

Monitoring groundwater like this is unique in Montana, according to Reiten, particularly for irrigation development. But there are successful examples in other states.

Before he came to Montana, Reiten worked for the North Dakota State Water Commission, where the same type of monitoring was going on that he helped start in Plentywood. He is working on another aquifer in Sidney, Montana, about 85 miles south of Plentywood, to develop a similar system.

“We’re applying the same methods there to try to develop that aquifer without affecting anything else,” Reiten says.

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Many conservation districts across Montana have water reservations on surface water, Yoder says, but Sheridan County Conservation District is one of only two districts that manages a groundwater reservation.

“I haven’t heard of any other places that have quite the extensive monitoring that we have and the time range that we have,” Yoder says.

There continues to be room for more water and improvement in how it’s used.

Wilvhom would like to see soil monitoring, so producers can know when to water and when they’re using too much. Devices are available that farmers could bury in the ground to monitor soil moisture and temperature.

Managing the aquifer has been “a collaboration to help the whole community do good,” Wivholm reflects later in the week, when Plentywood has reached -58 degrees with a windchill. “It helps the whole health of the whole ecosystem.”

The post An Ancestral River Runs Through It appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

A Community-Driven Path to Replenishing Groundwater in a Parched Region

A lone tractor trundles along a bumpy road in Banda, one of the most drought-prone districts in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Up until a few years ago, soil here would dry and crack into fissures deep enough for unwary cows to fall in. Today, as we drive toward a little village called Jakhni, we see rice paddies usually found only in much wetter climes. A large pond comes into view, and behind it, Jakhni.

Thanks to a revival of old farming practices and growing community involvement in all matters relating to water, this village is now known in India as a model jalgram, or water village.

Jakhni is a settlement of barely 1,600 people, mostly farmers. Its stony, hilly terrain is typical of Bundelkhand, an arid region spread across parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. This region receives between 800 and 1,300 millimeters of rainfall annually, but locals quip that like their children, who all tend to migrate for better opportunities, the rainwater runs off too. The rocks that lie beneath the region are not very porous, and there are relatively few aquifers (layers of underground water). As a result, most of the rainwater flows away from the region instead of being locally absorbed.

“Growing up, the water scarcity we experienced in Jakhni was scary,” Uma Shankar Pandey, a 52-year-old resident of Jakhni, recounts.

The post A Community-Driven Path to Replenishing Groundwater in a Parched Region appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Can Farmers Save the Great Salt Lake?

The Bear River flows out of Wyoming’s Uinta Mountains, winding 350 miles through sagebrush meadows and agricultural fields in Idaho and Utah before it fans out into wetlands 50 miles north of Salt Lake City. It’s the longest river on the continent that does not drain into the sea, and the largest source of water filling the Great Salt Lake.

One of the river’s last stops before it reaches the lake is Mitch and Holly Hancock’s farm, NooSun Dairy. Like hundreds of other farmers, the Hancocks divert water from the Bear River to irrigate crops like alfalfa hay and corn that feed their 3,000 cows.

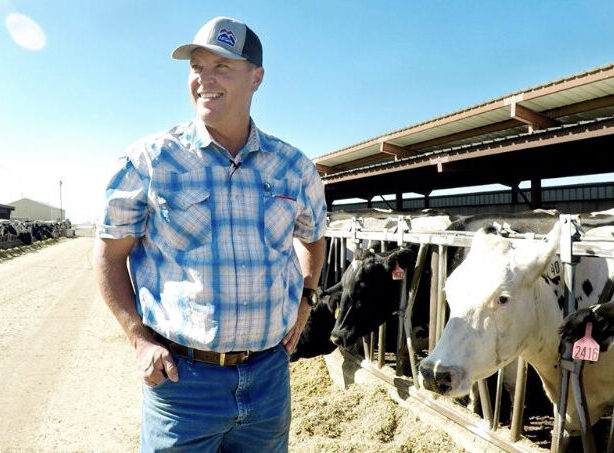

Mitch Hancock. Courtesy of Holly Hancock

Mitch Hancock. Courtesy of Holly Hancock

Since they live in the desert, the Hancocks spend a lot of time asking themselves how to protect and maximize their water, which Holly calls “one of our most valuable resources.”

“The only thing we can control on our farm is how efficient we are,” Holly explains. She was born on the farm in 1982, the same year her parents bought it. She says one of the family’s guiding principles for managing their business is: “How can we improve our processes so that we do more with less?”

Holly and Mitch recently made several improvements to their irrigation system to conserve water. They piped the farm’s earthen ditches so less water is lost to evaporation or seepage as it travels from the river to their fields. Mitch recounts that before the piping project, it took 45 minutes for water to reach one of their hay fields. Now it takes 45 seconds. “All that savings from point A to point B now stays in the lake,” Mitch says. “And every inch helps, right?”

Irrigation pipes and a hay field at the Hancocks’ farm. Courtesy of Holly Hancock

Irrigation pipes and a hay field at the Hancocks’ farm. Courtesy of Holly Hancock

Farmers and ranchers are key to helping solve Utah’s water crisis. In the face of a shrinking Great Salt Lake, irrigators like the Hancocks are stepping up to voluntarily conserve water in creative ways. And the benefits go both ways: Not only do such efforts keep the lake and its ecosystem alive, they also help agricultural producers grow food more efficiently.

Water is a particularly hot topic in Utah. The Great Salt Lake hit a record low in November 2022, shriveling its surface area to less than half of the historic average. This was a call to action for people throughout the region since the lake’s decline threatens to upend ecosystems and disrupt the local economy.

The lake pumps $2.5 billion into the state each year from industries like recreation, mineral extraction and harvesting brine shrimp. It supports 80 percent of Utah’s wetlands and 10 million migrating birds. And it even helps generate the powdery snow that draws up to seven million people per year to Salt Lake City to ski.

The 22-year-long megadrought in the American Southwest certainly played a role in shrinking the lake. But the main reason for its decline is that people are diverting water from the rivers that refill the lake. Three-quarters of the diverted water is used to irrigate crops — mainly grasses grown to feed cattle that produce beef or dairy, the state’s chief agricultural commodities. If people continue to use water at the current rate, the Great Salt Lake will likely disappear within five years, according to a report published by Brigham Young University in January.

Brine shrimp have been commercially harvested from the Great Salt Lake since 1950. Credit: Brianna Randall

Brine shrimp have been commercially harvested from the Great Salt Lake since 1950. Credit: Brianna Randall

Now for the good news: if agricultural and other outdoor water use is cut by one-third to one-half, the lake will likely refill to a level that can support local communities and the ecosystem. Voluntary conservation actions like the Hancocks’ irrigation upgrades are the most important — and most attainable — measures for keeping the Western Hemisphere’s largest saline lake alive.

Mitch believes that agriculture is sometimes framed as “the bad guy” because there’s a lack of understanding that farmers “want to be proactive” to help care for the water that sustains their business. He estimates that about half of the farmers in his area are participating in conservation projects.

That includes Joel Ferry, a fifth-generation cattle rancher. Like his neighbors, Ferry is setting an example of what he calls “water optimization”: growing as much or more using less water. On his family’s ranch, Ferry has installed 100,000 feet of irrigation pipe to replace leaking canals, and used a laser and GPS units to precisely level thousands of acres so the ground can be irrigated more efficiently. He also switched to no-till practices and cover crops and composting practices that all save water by not disturbing soil.

Credit: Chad Yamane / Ducks Unlimited

The Great Salt Lake hit a record low in November 2022: 4,188.2 feet.

These practices mean more water now flows into the wetlands at the north end of the Great Salt Lake, which are an oasis for wildlife. “In a normal drought cycle, these wetlands would have been dry and desolate,” Ferry says. But even during Utah’s driest years on record they stayed wet, thanks in part to his family’s voluntary conservation actions.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Ferry’s good intentions attracted attention. In 2022, he was appointed director of Utah’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Along with the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, the DNR has overseen the investment of $276 million in the state’s Agricultural Water Optimization Program since 2019. This program funds 50 percent of a farmer’s irrigation efficiency upgrades — like the Hancocks’ piping project — and also quantifies how much water will be conserved for the environment. Landowners must contribute at least 10 percent of the total project cost, but the other 40 percent often comes from federal cost-share, like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program funded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

In addition to saving water, Ferry says the optimization program helps agricultural producers “become more resilient and viable and hopefully more profitable on these landscapes.” On the shores of the Bear River where Ferry farms, he gets better crop yields from the bevy of water and soil conservation practices he’s put in place. Plus, he says, “I don’t have to drought-stress my crops because I’m able to get water to them when they need it.”

Joel Ferry speaks to a group at Antelope Island about water conservation. Credit: Brianna Randall

Joel Ferry speaks to a group at Antelope Island about water conservation. Credit: Brianna Randall

Overall, Utah has invested over $1 billion in all types of water conservation programs over the past two years. “This is a monumental, generational investment from the state in water conservation that’s just never been seen before,” Ferry notes.

The funding includes $250 million for installing tens of thousands of meters to track people’s outdoor water use. Research shows that just seeing how much water they consume results in people using about 25 percent less. Another conservation success has been offering incentives for residential homeowners to remove water-guzzling lawns, and banning a local practice of fining people who choose not to keep their grass green during the driest months. While the benefits of not watering a patch of lawn here and there might not be noticeable on the macro-level, “when you do it on tens of thousands of acres, it adds up” to a measurable difference in water savings, Ferry says.

Utah’s investment from the policy side is equally monumental, particularly if the state hopes to protect conserved water in streams, rivers, wetlands or the Great Salt Lake. “In the West, we have these ‘use it or lose it’ water laws. It’s a disincentive, in particular to agriculture, to save water and to leave it in the stream,” Ferry says.

Millions of migrating birds visit the Great Salt Lake every year. Credit: Chad Yamane / Ducks Unlimited

Millions of migrating birds visit the Great Salt Lake every year. Credit: Chad Yamane / Ducks Unlimited

He’s referring to the Prior Appropriation Doctrine, the set of laws that govern how water is administered in the western U.S. It was created to accommodate settlers moving west in the 1800s who hoped to “make the desert bloom,” says Emily Lewis, a professor at University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney School of Law.

The doctrine is based on seniority: the first person to divert water from a stream, river or lake for a beneficial use, like agriculture or mining, gets first dibs. If a senior right holder doesn’t use it, the water goes to the junior right holder next in line. This doctrine spawned the old adage: “Whisky is for drinkin’ and water is for fightin’.”

Historically, leaving water in a river wasn’t considered a beneficial use. This left the environment severely shortchanged. Most waterways in the West have no legal requirements to keep them flowing, so many streams are sucked dry during the summer. Fish, birds and plants all suffer as a result.

Credit: Chad Yamane / Ducks Unlimited

Thanks to the Prior Appropriation Doctrine — which spawned the old adage “Whisky is for drinkin’ and water is for fightin’” — leaving water in a river has not historically been considered a beneficial use.

But many western states, including Utah, are adapting the Prior Appropriate Doctrine to better reflect changing values. “We’re doing some serious spring cleaning here on the water rights system,” Ferry says.

Over the last five years, Lewis says the Utah Legislature has passed 64 water bills and “totally modernized its water law”. The state has been able “to go directly from step one to step ten”, Lewis says, because they were able to learn what’s worked for neighboring states like Colorado and Nevada, which have grappled for decades with water shortages.

This includes recognizing in-stream flow as a beneficial use and setting up systems that allow for water marketing – in other words, giving people the ability to lease, sell or donate some or all of their water to another use without forfeiting their property rights. In 2022, the Utah Legislature also allocated $40 million to create a water trust that will compensate willing sellers for moving water from out-of-stream uses to environmental flows to enhance the Great Salt Lake watershed.

Getting water from a farmer’s diversion all the way down a river and into the Great Salt Lake faces a gauntlet of administrative, legal, hydrological and engineering hurdles. Credit: Brianna Randall

Getting water from a farmer’s diversion all the way down a river and into the Great Salt Lake faces a gauntlet of administrative, legal, hydrological and engineering hurdles. Credit: Brianna Randall

The new water trust will build on lessons learned during pilot water marketing projects run by the Utah Water Banking Program. One of the first lessons was that people were excited about the chance to manage their water rights more flexibly. The program set out to start three pilot projects, but “ended up with four because we had such big interest,” says Lewis, who manages the program.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Over the past three years, Lewis has also learned that getting water from a farmer’s diversion all the way down a river and into the Great Salt Lake faces a gauntlet of administrative, legal, hydrological and engineering hurdles. She thinks one of the main challenges is “how to organize people’s thinking about water marketing because it’s just such a big topic.” The state just released a new website to help people get clearer answers about how to buy or sell water rights.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to restoring the Great Salt Lake is the lack of tools to track water as it moves through the system. Utah, like many places in the water-starved West, desperately needs better ways to measure how much water is actually flowing in its streams, canals, pipes or faucets on any given day. “It’s the linchpin,” says Lewis. “No one is going to lease or pay for water for the lake unless they know a wet water molecule is going to get from point A to point B.”

Despite all of these challenges, Lewis still firmly believes that water marketing “has to be one of the solutions” for refilling the Great Salt Lake. She points out that water right holders like Ferry participated in drafting recent policies so they reflect what will work on the ground for farmers and ranchers. “We’re talking silver buckshot solutions,” says Lewis. “We’re not talking about doing one hard thing, we’re doing 100 hard things all at the same time.”

Others in the state are still searching for a silver bullet. A lawsuit filed in September argues that the State of Utah should enact the public trust doctrine to protect the lake by summarily cutting off water to agricultural and other users to benefit the environment. This litigation will likely take decades to resolve. Meanwhile, the Great Salt Lake faces continued pressure from rapid population growth, climate change and competing demands for dwindling water supplies.

Credit: Chad Yamane / Ducks Unlimited

“We’re talking silver buckshot solutions. We’re not talking about doing one hard thing, we’re doing 100 hard things all at the same time.”

Ferry asks himself all the time what else Utah can do to ensure there’s enough water in the future for agriculture, communities and the environment. “It’s a three-legged stool,” he says. “We cannot neglect one of those legs or it’s game over.”

He keeps coming back to one tried-and-true approach: the best way to keep the stool from toppling — and the Great Salt Lake from disappearing — is to help people do more with less water.

Back at the north end of Great Salt Lake, Mitch and Holly Hancock are taking another step to do just that. This spring they will automate their irrigation system to make sure they’re not over-watering their drought-resistant crops, and to keep nutrients and topsoil from washing away.

Both Holly and Mitch say their long-term goal for Noosun Dairy is that it will be set up for their kids to farm in the future, if they want to. “Everything we do including water conservation is geared toward leaving it better than we found it,” Mitch says.

The post Can Farmers Save the Great Salt Lake? appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

People's Landscapes: Future Landscapes

A roundtable discussion consider future landscapes in the context of food, farming and conservation. People's Landscapes: Beyond the Green and Pleasant Land is a lecture series convened by the University of Oxford's National Trust Partnership, which brings together experts and commentators from a range of institutions, professions and academic disciplines to explore people's engagement with and impact upon land and landscape in the past, present and future. The National Trust cares for 248,000 hectares of open space across England, Wales and Northern Ireland; landscapes which hold the voices and heritage of millions of people and track the dramatic social changes that occurred across our nations' past. In the year when Manchester remembers the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo massacre, the National Trust's 2019 People’s Landscapes programme is drawing out the stories of the places where people joined to challenge the social order and where they demonstrated the power of a group of people standing together in a shared place. Throughout this year the National Trust is asking people to look again, to see beyond the green and pleasant land, and to find the radical histories that lie, often hidden, beneath their feet. At the fourth and final event in the series, Future Landscapes, panellists consider future landscapes in the context of food, farming and conservation, with panellists considering what we may want vs. what we will need from our landscapes in a post-Brexit Britain and beyond.

Speakers:

Alice Purkiss | National Trust Partnership Lead | University of Oxford (Welcome)

Helen Antrobus | National Public Programme Curator | National Trust (Introduction)

Dr Anita Weatherby | Research Programme Manager | National Trust (Chair)

Sue Cornwell | Head of Public Benefit and Nature | National Trust

Professor E.J. Milner-Gulland | Director, Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science | University of Oxford

Phil Jarvis | Environment Forum Chair | National Farmers' Union

Dr Prue Addison | Conservation Strategy Director | Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxford Wildlife Trust

For more information about the People’s Landscapes Lecture Series and the National Trust Partnership at the University of Oxford please visit: www.torch.ox.ac.uk/national-trust-partnership