trees

Planting Trees and Equity in the Arizona Desert

On a recent Sunday morning, the Barrio Centro neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona, was abuzz with activity. People from all walks of life were busy hauling dirt, planting saplings and building earthworks like berms and swales in the warm spring air.

They were part of a community planting event organized by Tucson Clean and Beautiful, a local nonprofit, as part of a larger, city-wide effort to fill street corners and vacant lots with groves of trees. The ultimate goal: to create more shade and increase heat resilience in the most vulnerable neighborhoods.

Tucson, sitting in the middle of the Sonoran Desert, is among the fastest-warming cities in the US. Over the past five decades, its average temperature has soared by 4.48 degrees Fahrenheit; last year, the town sustained more than 50 consecutive days with temperatures surpassing 100 degrees.

Youth employed by Tucson Million Trees work to place and irrigate young trees. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Youth employed by Tucson Million Trees work to place and irrigate young trees. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

However, the heat hits some areas harder than others. In neighborhoods in southern Tucson such as Barrio Centro, predominantly home to Latino and low-income communities, temperatures can be up to eight degrees warmer than the city’s average and a staggering 12 degrees hotter than affluent areas in the city’s north like the Catalina Foothills.

Such a difference is the legacy of decades of neglect that prevented the development of green spaces in the city’s poorer neighborhoods, argues Fatima Luna, Tucson’s chief resilience officer. “The south part of Tucson has been historically under-resourced, and there are not a lot of tree canopies there,” she says.

The extra heat endured by low-income neighborhoods often coincides with limited access to air conditioning, putting residents at risk of heat-related illnesses and even death. “This isn’t merely an environmental issue,” maintains Luna. “It’s a critical public health concern.”

Planting sessions take place from October through March. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

Planting sessions take place from October through March. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

To address these disparities, in 2020 Tucson set a lofty goal: to plant one million trees by the decade’s end. The commitment came as the city joined the 1t.org Stakeholder Council, a coalition dedicated to global tree restoration efforts. The US chapter of this council — which includes organizations like REI, the National Forest Foundation and Amazon, and cities like Dallas and Detroit — has pledged to plant over one billion trees collectively.

To pinpoint the areas most in need, Tucson city officials rely on an interactive dashboard powered by American Forests’ Tree Equity Score methodology. The tool crunches data like tree canopy cover, climate, the percentage of people of color, poverty rates, unemployment rates and the population of seniors and children to produce a single measure ranging from zero to 100 for each of Tucson’s 466 neighborhoods.

“This score serves as a compass, highlighting areas needing urgent attention,” Nicole Gillett, Tucson’s urban forestry program manager, explains. “Lower scores signify a greater need for investment.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Accessible to the public, the dashboard facilitates transparency and citizen engagement, enabling residents to track progress and report planting activities.

Planting sessions, organized in collaboration with local organizations such as Tucson Clean and Beautiful, occur on weekends throughout the planting season, which spans from October to March. During these events, volunteers are mentored by professional arborists who provide instructions on tree planting and maintenance.

Through a platform called Grow Tucson, residents also have the opportunity to actively co-design urban green spaces, ensuring they meet the needs of their community.

To date, about 100,000 trees have been planted. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

To date, about 100,000 trees have been planted. Courtesy of Tucson Clean and Beautiful

“Giving locals a personal stake is crucial,” notes Gillett. “It fosters purpose.”

The initiative prioritizes planting drought-resistant species indigenous to the region, such as blue palo verde, desert ironwood, desert willow and desert hackberry. “These species are particularly suited for urban environments because they grow at low elevations and depend entirely on rainwater for nourishment,” says Gillett.

In Tucson, where much of the surface is paved and impermeable, planting these trees can even play a role in revitalizing the city’s beleaguered streamsheds rivers, and creeks.

“Adding a rain basin with every tree is like giving the rain a direct pathway into the ground where it’s needed,” explains Gillett. “That way, it’s not just watering the trees but also replenishing groundwater and supporting streamflow.”

Some of these tree species can also contribute to addressing food insecurity in a city where nearly 20 percent of residents live more than a mile from the nearest grocery store, believes Brandon Merchant, a longtime Tucson resident and farm and garden education coordinator for the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona.

Merchant leads a program called SOMBRA, the Spanish word for shade and an acronym for Sonoran Mesquite Barrio Restoration Alliance. The initiative aims to plant 20,000 velvet mesquite trees across the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods by 2030 to build shade and enhance food security.

Young native species being grown for future planting. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Young native species being grown for future planting. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

Backed by the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management’s Urban and Community Forestry Program and the US Forest Service, SOMBRA began in 2021 after Merchant drew inspiration from a similar initiative in Portland, Oregon, focused on chestnuts.

“When we started thinking about it, we began noticing that mesquite trees are very much like chestnuts in that they can be grown in cities and can be used as a food supplement,” explains Merchant. “Indigenous communities living in this area have relied on it for thousands of years.”

The food bank organizes workshops about growing, pruning and harvesting techniques to educate community members on planting and caring for mesquite trees. “That’s a big part of it, giving people the skills to plant and tend to these trees for the long haul,” Merchant explains. The training also involves processing mesquite bean pods into flour ideal for baking bread, cookies and pancakes.

As part of the initiative, Merchant has teamed up with a local high school, a community farm and representatives from local tribes. Together, they have set up four cultivation sites where saplings are grown and nurtured until they are ready for transplantation. Only a few hundred saplings have been put into the ground thus far, but Merchant is optimistic about scaling up planting efforts this year.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

To date, Tucson’s initiative has led to the planting of approximately 100,000 new trees. Gillett says some of the trees planted first will start to have a small impact on shade and temperature, but it will take several more years to fully measure their impact.

The effort recently received a significant boost with a $5 million grant from the US Forest Service. This funding is part of a larger $1 billion commitment to urban forestry projects nationwide, established under the Biden administration’s flagship Inflation Reduction Act.

In addition to providing shade, mesquite trees can help alleviate food insecurity thanks to their bean pods. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

In addition to providing shade, mesquite trees can help alleviate food insecurity thanks to their bean pods. Courtesy of Tucson Million Trees

The grant funding will help the city run its recently opened Tree Resource Education and Ecology Center, a hub where seedlings are nurtured, and which can accommodate approximately 5,000 trees and plants. According to Gillett, this financial support will also bolster tree-planting capabilities and contribute to youth employment through specialized training initiatives.

As Tucson paves its path toward a cooler and more resilient future, municipalities across the country are paying attention. Gillet says she is frequently approached by leaders interested in setting up similar schemes in their own cities.

She believes Tucson’s approach can serve as a guiding model, as long as efforts are rooted in scientific principles, involve residents at every stage, and prioritize supporting vulnerable communities. “We’re not just planting trees,” says Gillett. “We’re planting equity.”

The post Planting Trees and Equity in the Arizona Desert appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

How a Colombian City Cooled Dramatically in Just Three Years

It’s mid-afternoon along Medellín’s Avenida Oriental, a traffic-clogged road that scythes through the heart of the second largest Colombian city, and Nicolas Pineda is crouched down on his haunches as cars zoom by on both sides.

Wrapped up in heavy duty workwear and armed with a machete, Pineda is weeding a thick strip of tree-lined greenery running between the lanes. He hacks at a patch of dead, browning bush and then pulls up a rogue, zig zag-shaped shrub beside his foot.

“Es bien bonita,” grins the 54-year-old, evidently pleased with his handiwork. “It’s very clean. That’s what I like to see: a clean, green city.”

Citizen gardeners at work. Credit: Peter Yeung

Citizen gardeners at work. Credit: Peter Yeung

Pineda has helped to sow and maintain hundreds of thousands of trees and plants across Medellín as part of a people-led scheme to fight back against extreme heat through a network of “Green Corridors” across the city.

In the face of a rapidly heating planet, the City of Eternal Spring — nicknamed so thanks to its year-round temperate climate — has found a way to keep its cool.

Previously, Medellín had undergone years of rapid urban expansion, which led to a severe urban heat island effect — raising temperatures in the city to significantly higher than in the surrounding suburban and rural areas. Roads and other concrete infrastructure absorb and maintain the sun’s heat for much longer than green infrastructure.

“Medellín grew at the expense of green spaces and vegetation,” says Pilar Vargas, a forest engineer working for City Hall. “We built and built and built. There wasn’t a lot of thought about the impact on the climate. It became obvious that had to change.”

Tree engineer Pilar Vargas inspecting a flower. Credit: Peter Yeung

Tree engineer Pilar Vargas inspecting a flower. Credit: Peter Yeung

Efforts began in 2016 under Medellín’s then mayor, Federico Gutiérrez (who, after completing one term in 2019, was re-elected at the end of 2023). The city launched a new approach to its urban development — one that focused on people and plants.

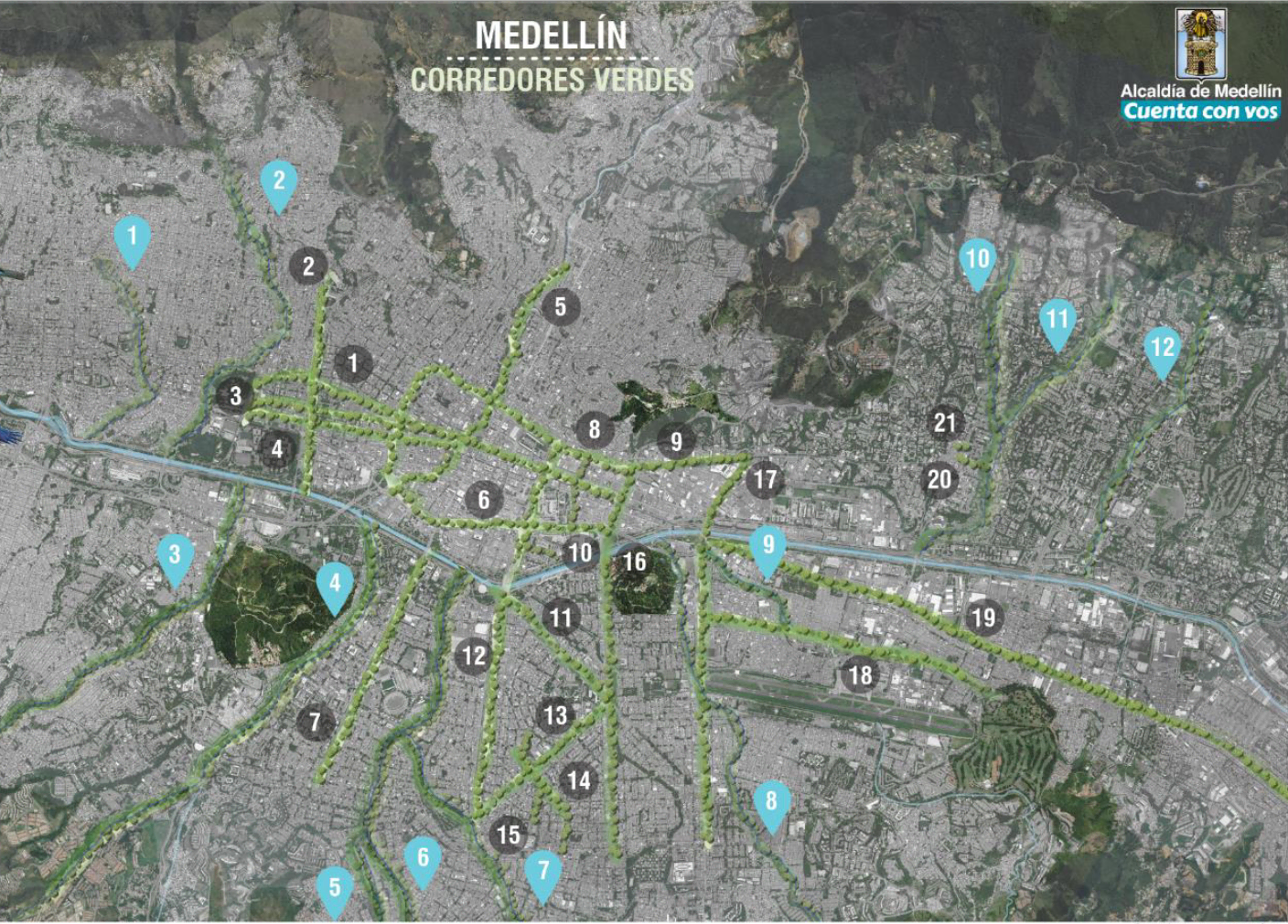

The $16.3 million initiative led to the creation of 30 Green Corridors along the city’s roads and waterways, improving or producing more than 70 hectares of green space, which includes 20 kilometers of shaded routes with cycle lanes and pedestrian paths.

These plant and tree-filled spaces — which connect all sorts of green areas such as the curb strips, squares, parks, vertical gardens, sidewalks, and even some of the seven hills that surround the city — produce fresh, cooling air in the face of urban heat. The corridors are also designed to mimic a natural forest with levels of low, medium and high plants, including native and tropical plants, bamboo grasses and palm trees.

Credit: Peter Yeung

Medellín’s temperatures fell by 2°C in the first three years of the Green Corridors program.

Heat-trapping infrastructure like metro stations and bridges has also been greened as part of the project and government buildings have been adorned with green roofs and vertical gardens to beat the heat. The first of those was installed at Medellín’s City Hall, where nearly 100,000 plants and 12 species span the 1,810 square meter surface.

“It’s like urban acupuncture,” says Paula Zapata, advisor for Medellín at C40 Cities, a global network of about 100 of the world’s leading mayors. “The city is making these small interventions that together act to make a big impact.”

At the launch of the project, 120,000 individual plants and 12,500 trees were added to roads and parks across the city. By 2021, the figure had reached 2.5 million plants and 880,000 trees. Each has been carefully chosen to maximize their impact.

A vertical garden at Medellin’s City Hall. Credit: Peter Yeung

A vertical garden at Medellin’s City Hall. Credit: Peter Yeung

“The technical team thought a lot about the species used. They selected endemic ones that have a functional use,” explains Zapata.

The 72 species of plants and trees selected provide food for wildlife, help biodiversity to spread and fight air pollution. A study, for example, identified Mangifera indica as the best among six plant species found in Medellín at absorbing PM2.5 pollution — particulate matter that can cause asthma, bronchitis and heart disease — and surviving in polluted areas due to its “biochemical and biological mechanisms.”

And the urban planting continues to this day.

The groundwork is carried out by 150 citizen-gardeners like Pineda, who come from disadvantaged and minority backgrounds, with the support of 15 specialized forest engineers. Pineda is now the leader of a team of seven other gardeners who attend to corridors all across the city, shifting depending on the current priorities.

Credit: Peter Yeung

“Medellín grew at the expense of green spaces and vegetation. We built and built and built. There wasn’t a lot of thought about the impact on the climate. It became obvious that had to change.” –Pilar Vargas

One of them is Victoria Perez. Back at the Avenida Oriental, where 2.3 kilometers of paving has been replaced by gardens, she is pruning a brush. The 40-year-old, like all of the other gardeners in the Green Corridors project, received training by experts from Medellín’s Joaquin Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden.

“I’m completely in favor of the corridors,” says Perez, who grew up in a poor suburb in the city of 2.5 million people. “It really improves the quality of life here.”

Wilmar Jesus, a 48-year-old Afro-Colombian farmer on his first day of the job, is pleased about the project’s possibilities for his own future. “I want to learn more and become better,” he says. “This gives me the opportunity to advance myself.”

The project’s wider impacts are like a breath of fresh air. Medellín’s temperatures fell by 2°C in the first three years of the program, and officials expect a further decrease of 4 to 5C over the next few decades, even taking into account climate change. In turn, City Hall says this will minimize the need for energy-intensive air conditioning.

Wilmar Jesus. Credit: Peter Yeung

Wilmar Jesus. Credit: Peter Yeung

Going forward, preventing and adapting to hotter temperatures will be a major and urgent challenge for cities. The number of cities exposed to “extreme temperatures” is set to triple over the next decades, according to C40 Cities. By 2050, more than 970 cities will experience average summertime temperature highs of 35°C (95°F).

A separate study estimated that in just one of Medellín’s corridors, the new vegetation growth would absorb 160,787 kg of CO2 per year and that over the next century 2,308,505 kg of CO2 will be taken up – roughly the equivalent of taking 500 cars off the road.

In addition, the project has had a significant impact on air pollution. Between 2016 and 2019, the level of PM2.5 fell significantly, and in turn the city’s morbidity rate from acute respiratory infections decreased from 159.8 to 95.3 per 1,000 people.

There’s also been a 34.6 percent rise in cycling in the city, likely due to the new bike paths built for the project, and biodiversity studies show that wildlife is coming back — one sample of five Green Corridors identified 30 different species of butterfly.

A map of Medellín’s Green Corridors. Credit: Medellín City Hall

A map of Medellín’s Green Corridors. Credit: Medellín City Hall

Other cities are already taking note. Bogotá and Barranquilla have adopted similar plans, among other Colombian cities, and last year São Paulo, Brazil, the largest city in South America, began expanding its corridors after launching them in 2022.

“For sure, Green Corridors could work in many other places,” says Zapata.

But there are some challenges. The corridors in the inner city areas have to contend with huge amounts of pollution as traffic piles up. Often drivers will also dump trash along the corridors. And the city’s homeless are forced to take shelter in the spaces.

“Like anything, nature requires maintenance from time to time,” adds Zapata. “You need to allocate a part of the budget for this.”

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

The previous administration “didn’t give enough money” to maintain the corridors properly, says Zapata, meaning some parts have become overgrown and dirty.

That’s a particularly tricky issue as the city now finds itself $2.8 billion in debt. Maintaining the city’s green corridors costs $625,000 a year, according to City Hall.

But now that he’s back in office, Mayor Gutiérrez has pledged to reinvigorate the project of urban planting. And experimentation with new technology, such as “geotextile” pavements that can soak up rain and bend to allow tree roots to spread, is already underway.

“The plan is to plant more Green Corridors and link them to even more hills and streams, recovering what we have already planted,” Gutiérrez tells Reasons to be Cheerful. “It will be a more green Medellín.”

The post How a Colombian City Cooled Dramatically in Just Three Years appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

California Redwoods Are Swiftly Recovering From Wildfire

Three great stories we found on the internet this week.

Greening up

In 2020, a wildfire tore through Big Basin Redwoods State Park in California’s Santa Cruz Mountains, charring the bark of the park’s namesake trees to an ominous black. But today, almost all of those towering old-growth redwoods are showing substantial new growth.

Not all species in the park are faring equally well: Researchers note that some birds and fish, including coho salmon and steelhead trout, are still many years from recovery. But the difference in the redwoods themselves is dramatic and encouraging.

Steam rises from burned trees in the park in November 2020. Credit: Dale Elliott / Flickr

Steam rises from burned trees in the park in November 2020. Credit: Dale Elliott / Flickr

In photos from April 2021, “All these trees are brown, they have no green foliage,” said biologist Drew Peltier, an assistant professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. “I pulled the image from today and I almost didn’t recognize it. The trees are so bushy now.”

Read more at the Santa Cruz Sentinel

Hair and care

Ever open up to your hairdresser about what’s stressing you out? Lots of people do. “We hear everything,” as Adama Adaku put it.

Adaku is among the 150 hairdressers in West and Central African cities who have recently earned the honorary title of “mental health ambassador” after undergoing mental health training. This training is an effort to fill in a massive gap: According to the World Health Organization, for every 100,000 people in this region, there are an average of 1.6 mental health workers (compared to the global median of 13).

Organized by the nonprofit Bluemind Foundation, the three-day training equips hairdressers with skills such as asking open-ended questions and picking up on nonverbal signs of distress. “People need attention in this world,” said Tele da Silveira, another hairdresser who completed the training. “They need to talk.”

Read more at the New York Times

Health is wealth

Cash assistance programs have been shown to improve children’s health and well-being by alleviating early childhood poverty and food insecurity — issues that disproportionately affect Indigenous communities. That’s why a Seattle-based nonprofit has created the first-ever guaranteed basic income program exclusively for Indigenous families.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Called the Nest, the program will provide monthly cash assistance to 150 families for the first three years of their child’s life. It will also offer other support, including doula services and a financial sovereignty class.

The program also seeks to combat the high maternal mortality rates among Indigenous people in the US. “There are high disparities that are rooted in historical trauma and collective violence from colonization, genocide, forced relocation and boarding schools combined with lack of access to basic health care,” the Nest’s director, Patanjali de la Rocha, told High Country News. “Guaranteed income helps not only on an individual level, but it also helps people heal intergenerationally.”

Read more at High Country News

The post California Redwoods Are Swiftly Recovering From Wildfire appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

North Sydney and the Expressway Tree

With the festive season over, decorations have almost disappeared from shop windows and front gardens. Suburban frontyard light displays have been packed away, and the dry, dead remains of Christmas trees protrude from green waste bins. The decorations that are still up seem stubborn or stale, behind the times, which have churned on into an already stressful new year.

Driving through North Sydney, I’m not yet thinking about Christmas decorations or anything much except making sure I’m in the right lane for the Arthur Street turnoff. Berry Street splits in two like ram’s horns, left to go north, right to the bridge. Choose wisely, for the Warringah Expressway awaits below. There’s an intensity to this intersection, perched as it is at the edge of the North Sydney high-rises. Here the view opens up towards the sky and the harbour and the far shore of the eastern suburbs. Below is fifteen lanes of surging motorway traffic although this is, from this high vantage point, out of sight.

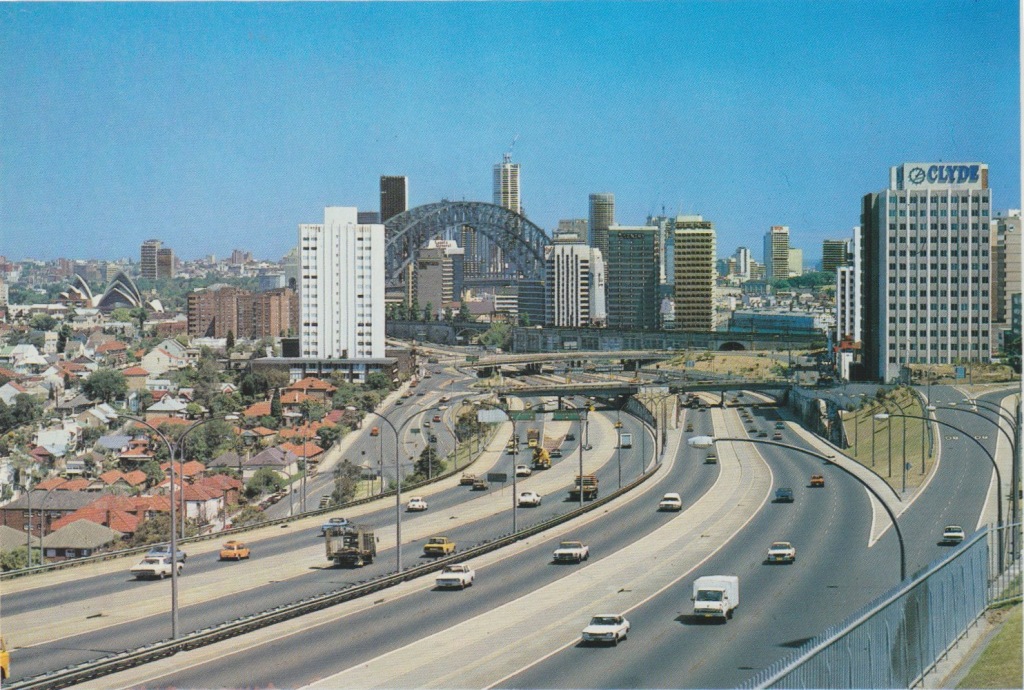

(The Warringah Expressway, quite some time ago: see the film that documents its construction for details of its construction and scenes of mass demolition and earthworks accompanied by a chirpy orchestral soundtrack.)

(The Warringah Expressway, quite some time ago: see the film that documents its construction for details of its construction and scenes of mass demolition and earthworks accompanied by a chirpy orchestral soundtrack.)

I turn into the lane closest to the edge, which is hemmed in by a barrier and a railing. Beside the lane is a narrow strip of concrete, which runs the length of the road. Something glittery catches my eye. A short way along the roadside, from a crack in the concrete, against the odds, a tree is growing. It is a casuarina tree, about two metres high, roughly the shape and size of a Christmas tree. Evidently someone had noticed this, as its lower branches had been decorated with glittery plastic ribbons. What a tenacious little tree, there amid the concrete and the traffic, thriving where no tree is meant to grow.

I might have noticed the tree and keep going on my way, but instead I change lanes and travel back around the block. I park the car in a laneway between two rows of office buildings, where the mood is concrete, security cameras, and garage doors with ads for Magic Button (featuring the cheerful mascot of a magician figure in a tuxedo with a button for a head, pressing down on the top of it to release a shower of sparks).

No one much is around, a combination of it being the first week of the year and the recent huge upsurge in Covid infections. This means there’s less traffic, too, which is helpful as I dash across the road, to the siding just before the strip of pavement with the tree. Here it’s wide enough to stand to take a photo, though I feel conspicuous as the cars go past. Like the tree, here by the precipice of the motorway, I stand in an unlikely place. For a moment I take in the view of the lanes of traffic below and then the harbour, before dashing back across to safety.

Later, I look up the slices of time captured by Google Street View to follow the tree’s growth. It’s not there in November 2017, but then by the next image, October 2018, it’s a small, sturdy sapling. By November 2019 it’s up above the railing. I watch it get taller over 2020, then 2021, until the last capture in May, in which it looks much like it does now in its decorated form. I think of it growing these last four years, nourished by the sunlight and the rain, as the skies filled with bushfire smoke for months, and then the traffic dwindled as the city went through lockdowns. Maybe it was during lockdown that the person who decorated it had noticed it, in that time when local details were our comfort.

I walk the long way back to the car, deciding to look around North Sydney a little bit. My mental map of it is outdated by decades: going past on the expressway I still look up expecting to see the clock/temperature that used to be up on the side of the Konica Minolta building (then the Sunsuper building). I had a childhood association with it, where it represented for me both the high rise world of business and something closer to home: the orange numerals resembled a bedside alarm clock. A few years ago the view of it disappeared when a new gleaming glass office tower was built in front of it, but I could see it was still there, a black box high up in the top corner, visible in the gap between the buildings.

All was quiet around the offices buildings, apart from a few construction sites and removalist vans. The smokers’ courtyards were empty, and few people waited to cross at the street corners. I watched my reflection move across mirrored glass that sealed off the views into office windows. Only real estate signs gave a sense of what might be inside them.