Academia

Australia’s cost-of-living crisis isn’t about the price of groceries. It’s about wealth distribution*

Here’s a piece I wrote for The Guardian. It’s also at my Substack. Some of it is Australia-specific but some may be of more general interests

The policy debate about the cost of living is among the most confused and confusing in recent memory. All sorts of measures to reduce the cost of living are proposed, then criticised as being potentially inflationary. The argument implies, absurdly, that reducing the cost of living will increase the cost of living.

The issue here is that the “cost of living” is an essentially meaningless concept, rather like the sound of one hand clapping. The problem isn’t the cost of buying goods, but whether our income is sufficient to pay for those goods. For most of us, that means the real (inflation-adjusted) value of our wages, after paying tax and (for homebuyers) mortgage interest.

In the famous Harvester decision of 1907, Justice Henry Bournes Higgins of the Arbitration Court determined that a family of five could live in “frugal comfort” on 42 shillings ($4.20) a week, less than the price of a cup of coffee today. On this basis, he set the basic wage at 42 shillings a week, or about nine cents an hour for the then-standard 48-hour working week.

Looking back over the past century or so, the cost of buying a basic bundle of necessities (and some modest luxuries) has risen almost continuously. But, fortunately, wages and other incomes have risen much faster. So while people complain about the cost of living today, few of us would want to go back to the frugal comfort of 1907.

Looking at more recent history, the consumer price index rose faster for much of the 1980s than it has done over the last few years. Inflation was a significant problem for macroeconomic management and financial markets. But the “cost of living” was not a big issue because wages were indexed under the Prices and Incomes Accord. Some small reductions in real wages were compensated for by the reintroduction of Medicare and improvements in superannuation.

The Accord, focused on real wages, produced a gradual decline in inflation rates, while maintaining standards of living. By contrast, the current discussion of policy in terms of the cost of living has produced incoherent policies and declining living standards.

The natural policy response to concerns about the cost of living is to seek reductions in prices that are politically sensitive (such as petrol, electricity and basic groceries) and to provide ad hoc relief to groups seen as “doing it tough”. This has included wage increased to offset inflation for particularly “deserving” groups (minimum wage earners and aged care workers), even as the real value of most wages remains far below pre-pandemic levels. Labor estimates the value of their 2022-23 cost-of-living relief package at $14.6bn.

In the neoliberal context, any benefits given to one group of wage earners or welfare beneficiaries must be offset by costs imposed on another. The ad hoc nature of policy responses to the perceived cost-of-living crisis reflects the incomplete and inadequate nature of this framing of the issue. But it is not the worst consequence.

The crucial problem with “cost of living” thinking is the implication that the problem will be resolved by reducing the inflation rate, ideally with a rapid return to the Reserve Bank target range of 2-3%. In this way of thinking, the worst thing that could happen is for wages to rise enough to offset past inflation. Such an adjustment, it is claimed, could set off an inflationary spiral.

A rapid reduction in inflation, achieved by holding real wages below their pre-pandemic level suits the institutional interests of the Reserve Bank, which are centred on its primary objective of price stability. But Australian workers would be better served by a gradual reduction in inflation, without real wage cuts, as was achieved in the 1980s under the Accord.

If the decline in real wages wasn’t bad enough, the Albanese government has made matters worse by eliminating the low and middle income earners tax offset (LMITO), introduced in 2018 by then treasurer Scott Morrison as part of a tax reform program designed to culminate in 2024-25 with stage three, massively skewed towards high-income earners.

LMITO was supposed to expire in 2020, but the Morrison government repeatedly shied away from raising taxes on middle-income earners at a time when real wages were failing.

Jim Chalmers and Anthony Albanese had no such qualms and scrapped LMITO from 2022-23 onwards. Over the government’s remaining term, the resulting increase in taxes will more than cancel out all the cost-of-living relief trumpeted in the last budget. Meanwhile, the stage-three tax cuts will ensure that high-income earners are returned to the lowest average tax rates in recent history, last seen under the Howard government’s final package of tax cuts.

In the end, the “cost of living” isn’t about the prices on grocery shelves, it’s about the distribution of income. In Australia, income has shifted from wages to profits and from low- and middle-income earners to those in the top 10% of the income scale and, even more, to the handful of “rich listers” whose growing wealth has outstripped that of ordinary Australians many times over.

- More precisely, income distribution, but I don’t get to write my headlines.

Cartoon: Billionaire buttinsky on campus

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

What if there were far fewer people?

One of the most common arguments in debates about environmental crisis is: “it’s the rising population, stupid.” There are just too many human beings, using up too much stuff, leaving too little space for everyone else. The next step is often to gesture towards some kind of population control, or just to leave the issue hanging.

Whatever you think of that position, I’ve been struck lately by the increasing prominence of its diametric opposite. This holds that the problem we face – or will soon face, anyway – is that there are actually too few of us. Consider this opinion piece from the New York Times back in September (only the latest in a series of pieces the NYT has published on the topic, often with much the same message. Here’s one from 2021, and another from 2022). The real problem, it suggests, is that the human population will not only peak in 2085, but that it will then decline, perhaps precipitously. Within a couple of hundred years, there might be only be 2 billion of us left. The claim is not, note, that population will fall in one country or other – we’re familiar with that idea. The claim is that the global population is set to decline, perhaps precipitously.

The key question is: why would this matter? There are several reasons for thinking it wouldn’t, actually. Liberals will say that if people freely decide not to reproduce, that’s their business. Some population ethicists might retort that no-one is wronged by not being brought into existence. And then, of course, there’s the biggie: fewer people would mean much more space for every other living thing. We have crowded out (or killed) so many of our fellow creatures. In a post-Anthropocene world, wildlife could recover some of its past glories. Which is why some think a smaller population would be a good thing for multiple reasons.

Why, then, think we should worry about declining numbers of people? Well, what reasons does the NYT piece provide? The argument could be a lot more direct. But the key suggestion seems to be that larger populations generate more innovation, and hence more (per capita) economic growth. That, of course, will hardly persuade people who think more growth is something we can ill afford on a limited planet. We’re also, obviously, owed an account of why less growth would necessarily mean lower levels of well-being (FN). But it seems the idea is simply that fewer people means fewer Mozarts, fewer Marie Curies, fewer Henry Fords.

If that is the argument, it brings us close the position of prominent longtermists (though the author does not make the link). Some longtermists have wondered, after all, whether most animals might not be better off dead anyway. By contrast the more human beings there are, the greater the chance that we eventually colonise the stars and become Ultra-High-Well-being Cyborgs . Perhaps today’s twenty-something in a rented flat and a precarious job – and wondering whether she could ever afford to raise children – just needs to think of that cyborg composing twenty symphonies before its synthetic lunch, and get breeding.

. Perhaps today’s twenty-something in a rented flat and a precarious job – and wondering whether she could ever afford to raise children – just needs to think of that cyborg composing twenty symphonies before its synthetic lunch, and get breeding.

Somehow, I don’t think that’s likely to cut the mustard. But I am curious about the emergence of this trope, which bemoans the declining population long before it happens. It seems distinct from arguments decrying the declining birth rate in some continents rather than others (the favoured topic of ‘great replacement’ conspiracy-mongers). But I am curious what its political or intellectual origins are, and what, if anything, might be said in favour of it. Why, then, would it matter if there were far fewer of us?

(FN). We’re also owed an account, of course, of why diminishing human well-being wouldn’t be more than compensated for by greater opportunities for animal flourishing. The NYT piece is a little evasive here. It acknowledges that a lower population might be a boon to the environment, but replies that decarbonisation and the protection of biodiversity has to happen now: to wait for population decline as a solution is to wait too long. Well, sure. But that doesn’t mean we can push aside bigger, wider questions about the relationship between human population and the wider environment!

The gallon loaf

I’ve been working a bit on inflation and the highly problematic concept of the ‘cost of living’ (shorter JQ: what matters is the purchasing power of wages, not the cost of some basket of goods). As part of this, I’ve been looking at how particular prices have changed over time, focusing on basics like bread and milk.

One striking thing that I found out is that, until quite late in the 20th century, the standard loaf of bread used to calculate consumer price indexes in Australia weighed 4 pounds (nearly 2kg). That’s about as much as three standard loaves of sliced bread. Asking around, this turns out to be the largest of the standard sizes specified in legislation like the Western Australian Bread Act which was only repealed in 2004, AFAICT.

Going back a century or so further, the Speenhamland system of poor relief in England specified the weekly nutrition requirements of a labouring man as a ‘gallon loaf” of bread, made from a gallon (about 5 litres) of flour, and weighing 8.8 pounds (4kg). Bread was pretty much all that poor people got to eat, so the amount seems plausible.

But why one huge loaf rather than, say seven modern-size loaves? And turning that question around, why are our current loaves so much smaller?

I haven’t been able to find anything about this. Looking for images of these gallon loaves is difficult, because of the popularity of ‘loaf tanks’ made in the shape of bread loaves and with a capacity measured in (US) gallons.

Whenever I see a development like this, I think about shrinkflation, the process of reducing the size of a product as a surreptitious way of increasing the unit price. But shrinkflation is ultimately a cyclical process. When the standard size has been shrunk as far as it will go, it is replaced by a new ‘jumbo’ or ‘economy’ size, the same as the original standard size.

So, my best guess is that it is all to do with that proverbially marvellous invention, sliced bread. Sliced bread requires a standard size, and small is easier to handle. Also (guessing here), sliced bread may not keep as well, so we buy smaller loaves more frequently.

I’ve had some useful responses from Bluesky and Mastodon on this (I shudder to think how XTwitter would respond if I were still there), and now I’m throwing it over to my newsletter and blog readers. Any info would be appreciated.

American Gerontocracy, Explained

2024 is here, the year of the election. As the world begins to tune in to the greatest show on X, the question on everyone’s lips is:

Why the hell is everybody so old??

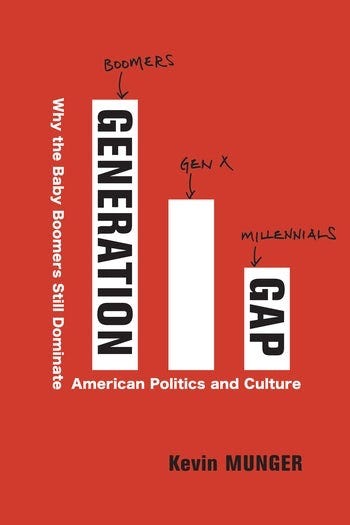

In the summer of 2022, I published a book predicting this:

elite electoral politics will see a clear and extremely high-profile generational turning point in 2024. President Joe Biden begins his term as the oldest President in history; in 2024, he will be eighty-two years old. He at one point indicated that he intends to serve as a “transition” President, and that he might be the first President to decline to seek re-election in decades. If he does run, his advanced age will be a central issue throughout the campaign.

First, the facts: in 2024, either Trump or Biden would be the oldest person to win a presidential election. We have the second-oldest House in history (after 2020-2022), and the oldest Senate. A full 2/3 of the Senate are Baby Boomers!

Not only is the age distribution of US politicians an outlier compared to our past—we also have the oldest politicians of any developed democracy. And not just the politicians, but the voters, too: more Americans will turn 65 years old in 2024 than ever before—and given macro-trends in demography, maybe than ever again.

The approach I take in the book is very different from the rest of my research. In contrast to a tightly-controlled experiment, analyzing phenomena of this scope does not allow for neat causal explanations. The “temporal validity” issues that arise when studying social media are because they change too quickly; here, the problem is more “temporal illegibility,” the inability of our preferred tools to register “causes” that unfold over the course of decades.

Paul Pierson’s excellent book Politics in Time makes this point in excruciating detail. The research methods in vogue in quantitative political science (the ones I tend to use!) are like the vision of the Tyrannosaurus Rex from Jurassic Park: they can only detect movement, at the speeds typical of medium-sized mammals.

A common exercise in research design classes is to discuss the “ideal experiment” to study a given question. If money, power and ethics were no constraint, what experiment would you run? It’s useful, thinking about what it would mean to randomly assign one state to only broadcast Fox News and another state only MSNBC. But the very idea of an experiment breaks down at the scale of generational politics.

It doesn’t even make sense to think about randomizing, say, “generation size” to see how much that causes generational power when a given cohort turns 65. Modifying society at that temporal scale means that there’s nothing left when the experiment is over, no fixed point or control group against which to compare the results. (Footnote 1 for more)

The inability to conceive of an ideal experiment suggests that the relevant question is ill-posed. When I talk about “Boomer Ballast,” the outsized power wielded by this generation in the 2010s and 2020s, people sometimes ask: “how much of this is just because there were so many of them born at the same time?”

This question is unanswerable and therefore, in my view, meaningless. Just as the speed of social media makes “ceteris paribus” (all else equal) comparisons impossible, so does the speed of generations vizaviz the temporality of the human life cycle, the age of the country, etc.

And on the “just because” part. I’ve found that this is a common response to the presentation of a descriptive research result: people chalk it up to the first causal mechanism that pops into their head, in a dramatic inversion of the usual skepticism applied to causal claims.

Both this issue and the T.Rex-vision problem are legacies of the misapplication of Hume’s model of causality, itself a more narrow definition than Aristotle’s…but back to Boomer Ballast.

The challenge of differentiating the effects of age, time period, and cohort (the “APC” problem) is a statistical nightmare—especially because the data we have access generally only goes back a few decades. But the premise of the problem is that, yes, all three of age, period and cohort have effects…so by definition, no effect is just because of any one individual cause.

That’s why I don’t really care about resolving the APC problem. My claim is that a confluence of largely unrelated factors will cause generational conflict to become a central cleavage in US politics in the 2020s. This means holding fixed the time Period of analysis and treating Age (there are a lot of old people) and Cohort (those old people are Baby Boomers) as two distinct types of causes of the present generational conflict.

The politics of generations is affected by raw demography, growing longevity, and unequal power accumulation alongside the rapid evolution of communication technology and the development of online communities that enable younger generations to ignore geography and the need to gain knowledge from elders. The two main “causes” are the accumulated power of the Boomer generation and the information technology revolution; the tension between these causes is the main “effect,” generational conflict, played out in the realms of politics and culture.

This conflict has a zero-sum dimension, as younger and older generations jostle over a fixed fiscal budget, with mutually exclusive preferences. Boomers want more money for Medicare and Social Security; Millennials and Gen Z want money for student loan debt forgiveness and climate change amelioration. But in another important sense, the tension between Boomer Ballast and the internet revolution is negative-sum, and potentially even more concerning for the viability of the United States as a system. This insight comes from Karl Deutsch’s classic 1963 book The Nerves of Government, which conceives of government through the analogic lens of a brain—or, updated to today, as a computer.

The book is broadly concerned with communication, the way that information flows from citizens to the government, within the government, and then back to the citizens in a circularly causal feedback loop. In contrast to many of the broad accounts of government—before or since—Deutsch conceives of government as cybernetic, and thus primarily concerned with adapting to a perpetually changing environment. This dynamism produces an unresolvable tension; between the openness to new information required to adapt, on one hand, and the commitment of societal resources required to address present problems:

“In addition to being invented and recognized, new solutions and policies must be acted on, if they are to be effective. Material resources must be committed to them, as well as manpower and attention. All this can be done only to the extent that uncommitted resources are available within the system” (p164).

Applying Deutsch’s framework to the biological realities of the human life cycle, we see that our society has an unusual degree of resources committed. The government cannot change the shape of the demographic pyramid, except decades in advance. Boomer Ballast means that a disproportionate amount of our economic, social and political human capital is invested in an illiquid response to the postwar, 20th century environment. Our demographic structure, compounded by our economic fortunes, granted us an unusually high degree of adaptability. And we flourished.

But the Boom in adaptability led naturally to a bust. In normal circumstances, this would still entail some future cost, as we had fewer untapped resources to devote to new problems. Our society is like a sluggish laptop with too many browser tabs open, too many resources devoted to maintaining things as they are, to be able to do new things quickly.

The advent of the internet compounds the problem of our present over-commitment. It will take decades for the full implications of the internet and related technologies to filter through and fundamentally reshape human society, but Boomer Ballast means that this process is stunted in the contemporary United States.

To deploy new “solutions and policies” suited for the digital age, we will need to move beyond the inherited structures of the 20th century. The biological passing of the Boomer generation is inevitable, but the organizations and structures the Boomers built or reinforced will long outlive them.

Deutsch sees this as an inevitable challenge facing societies that hope to thrive beyond a single human lifespan, and he warns us to “avoid the idolization of ephemeral institutions”—or, in DJ Khalid’s terms, The First Amendment is Suffering From Success. We must be willing to acknowledge that institutions designed for past times and past generations cannot possibly take advantage of contemporary technology and the human social structures it makes possible.

And we must also ensure that the conditions are right for new generations to build institutions in their place. At the risk of getting too cybernetics-y, a final quote from Deutsch:

The demobilization of fixed subassemblies, pathways or routines may thus itself be creative or pathological. It is creative when it is accompanied by a diffusion of basic resources and, consequently, by an increase in the possible ranges of new connections, new intakes, and new recombinations. In organizations or societies the breaking of the cake of custom is creative if individuals are not merely set free from old restraints but if they are at the same time rendered more capable of communicating and cooperating with the world in which they live. In the absence of these conditions there may be genuine regression (p171).

Genuine regression. Flusser’s fall into unconscious functioning is the result of being surrounded by technical images we cannot understand or control. Deutsch argues that a similar result occurs when individuals who are set free from “the cake of custom” are not simultaneously empowered to communicate and cooperate with the world.

That’s an excellent description of what’s happening today: a fully armed and operational internet/social media/smartphone stack, deployed to the majority of humans in under a decade, is reshaping societies, economies, cultures, families. But because this “freedom” comes without increased capacities, it produces mostly meaninglessness, alienation and vitriol. And Boomer Ballast makes the problem much worse.

Am I able to provide maximally rigorous statistical evidence for the previous paragraph? No, sorry, we live in a fallen world, and the position that we can know nothing unless proven the highest standards of rigor is cheap positivist nihilism. My book triangulates various kinds of evidence towards this central claim, and history (rather than contemporaneous peer reviewers) is the only real judge of the value of my perspective.

And so far, in my humble opinion, so good—2024 will be the year that Boomer Ballast becomes impossible to ignore. The demographic structure of the United States is as much a political institution as are presidential primaries, and it deserves full consideration by political scientists as such.

Much more, dear reader, if you buy my book.

Footnote 1:

Early-career John Dewey, when confronted with the epistemic challenges to science/democracy posed by Walter Lippmann, considers biting this bullet: he sees the Soviets as having an advantage over democracies because they are actually able to conduct five-year-long experiments. (They weren’t, actually, but Chinese cybernetics comes much closer to fulfilling this vision, of crossing the river by feeling the stones.)

Eventually he realizes that he cares more about democracy as creative freedom than he does about scientific certainty—a decision with which I agree. Of course, contemporary scholars of Dewey are frustrated by the imprecision of his use of terms like “democracy” and “science,” but that’s sort of begging the question.

Why is Political Philosophy not Euro-centric?

In a recent post about unfair epistemic authority, Macarena Marey suggests that

In political philosophy, the centre is composed of the Anglophone world and three European countries…

One can think of “the center” in terms of people or of topics. Although Marey’s post is clearly about philosophers not philosophies, and I agree with her, one can also address the issue of “the centre” about philosophies.

For my part, I wonder the opposite: how come political philosophy is not Euro-centric? If Anglophone and European philosophers dominate the field, as indeed they do, why doesn’t European politics dominate political philosophy, too?

My point is not that European politics should dominate political philosophy, but that it is surprising that it does not. First, because philosophers often sought solutions to the political problems of their time (think of Montesquieu or Locke on the separation of powers; of Paine and Burke debating human rights during the French Revolution etc.). Second, because the European Union is a political innovation on many respects; had a philosopher presented the project (“imagine enemies at war pooling their resources”), it would have been dismissed as utopian. Finally, because EU is a complex organization which deals with enough topics that it is hard not to find yours. Topical, innovative, and complex – but not of interest for European hegemonic philosophers: is this not puzzling?

You doubt. But how would political philosophy look like if it was Euro-centred? Certainly, renewed — by philosophical views tested at the European level or inspired by the European institutions. For example, there would be philosophical analyses of “new” topics such as:

- Freedom of movement – a founding freedom of the European union over the last 70 years. Surprisingly, there is not a single philosophical treaty on this freedom today (although freedom of speech, of assembly etc. are well represented); all philosophical studies reason as if it were natural to control immigration, as if open borders were an unrealistic utopia – in short, as if the EU did not exist (neither Mercosur‘s or African Union‘s institutions).

- Distributive justice between states or within federal states – a political reality since the 1950s or earlier. But since the 1970s, philosophers have been praising Rawls, Walzer, and others who argue that redistribution between states is not a matter of justice (no reviewer have ever asked them whether the existing European/international redistribution was unjust etc.).

- Justice of extending / fragmenting states and federations of states – today, cosmopolitanism is considered in opposition to nationalism, not to regionalism or federalism; secession/ unions are under-discussed in theories of justice or critical race theory; there are more philosophical studies on just wars than on peace etc.

Many other sources of philosophical renewal are not specific to the European Union but could have been be activated if political philosophy was Euro-centric. For example, international aid has been institutionalized since the WWII (as I have briefly shown here), but prominent philosophers reason about its justice as if it did not exist. Less prominent philosophers should adapt to the existing terms of the debate.

In short, if political philosophy was a little more Euro-centric, its questioning would be renewed and more realistic. If it is not, the problem of political philosophy is not “Euro-centrism” but “centrism” tout court: we tend to organize around a few “prominent philosophers” and their views rather than around originality, pluralism, and truth.

New Year Gifts

It’s still New Year’s Day in places, but the world of academia seems to be back to work, and sending me a variety of gifts, some more welcome than others. Coincidentally or otherwise, it’s also the day I’ve moved to semi-retirement, a half-pay position involving only research and public engagement.

Most welcome surprise: an email telling me I’ve been elected as a Fellow of the Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory. In the way academia works, some friendly colleagues must have proposed this, but I had no idea at all

Most culturally clueless: A request for a referee report, due in three weeks. This is January in Australia – only the most vital jobs get done

Most interesting: An invitation to join the editorial board of Econometrics, an MDPI journal in which I have published an article of which I am quite proud, though of course it has received almost no attention. MDPI is a for-profit open access publisher, which regularly deals with accusations of predatory behaviour. A search reveals that the existing editors have resigned, something which is happening a bit these days.

I’m in n>2 minds about this. I think that journal rejection rates in economics are absurdly high, in a way that damages intellectual progress. Eric has expressed the same view regarding philosophy, which is closer to economics in cultural terms than any other discipline (Macarena’s post is highly applicable to econ).

On the other hand, I’m always dubious about the motives of for-profit firms (that includes the “reputable” firms like Elsevier and Wiley).

And on hand #3, I’ve just semi-retired, and I don’t feel like taking on a fight in which I have no dog.

So, I’ll probably stick with the plan of spending more time at the beach, working on my triathlon times, and trying not to get too depressed about the state of the world, at least those bits I can do nothing too change.

New year’s resolutions that are not about me

Happy 2024 everyone! May there be no more wars, no more avoidable suffering, and justice for all. That’s a steep wish-list, but then I am one of those who thinks that giving up is not an option, and that [almost] everyone has opportunities to contribute to make us move into that direction.

In that spirit, I made three resolutions for 2024: one for myself, one for a specific very vulnerable person, and one political resolution, for society at large.

I can already hear the cynic laughing: New Year’s resolutions don’t work! Resolutions are for weak people who could have solved their problems long ago if they were a little more decisive. With New Year’s resolutions we only fool ourselves. The cynic pours himself another drink, and has a good laugh at those who make resolutions.

This hip cynicism underestimates the power of rituals in our lives, including the rituals around intentions to make meaningful changes. Yes, the cynic is right that we can make resolutions on any day of the year. The formulation of a resolution often follows a significant personal experience; I’ve met several survivors of cancer who made big changes to their lives. Or we need a long enough period of peace of mind that allows us to reflect, to look in the mirror and ask ourselves what we want to do differently with our lives. But of course this can also be done at any other time of the year, as long as we first have the necessary mental space. There are plenty of people who return from their summer vacation and resolve to exercise more or find another job. But the period around New Year is also a time of some contemplation for many, and thus an excellent time for reflection on what we would like to see different in our lives.

The cynic is also right that we won’t get there by merely formulating good intentions. It takes more to make them succeed. But it only takes a few minutes to find the recipe for success on the Internet: find out how to turn intentions into a habit; don’t make too many resolutions; translate them into small, concrete actions; preferably carry out your resolutions with others or find another way to get someone to encourage you and keep you accountable; and reward yourself for the behavioural change that is needed.

Usually good resolutions are about ourselves. We want to quit smoking, drink less, lose weight, exercise more, work less, get another job, and so on. But we can also make resolutions that are not primarily about ourselves, even though we remain the person in charge.

Another type of resolution is about doing something for a concrete other person who could use our support. We take that child of friends who has special needs under our wing for a day a few times a year so that this child feels special and less lonely, and their parents can have a day to recover from the burdens of care that special needs almost inevitably bring. We commit to visit that lonely neighbour down the street once a week, or at least stop to have a chat when we meet her in the street. We offer the vulnerable boy next door help in finding a suitable job. In some communities and neighborhoods this may perhaps come naturally, but in less close-knit neighbourhoods this is also possible — simply, because someone takes a first step (as the pub-owner in the most recent Ken Loach film The Old Oak vividly illustrates).

The third group of resolutions are about society as a whole. I would think of them as political resolutions, with ‘political’ very broadly defined. We can’t sit back and hope that 2024 will bring us a better country and a better world: we will have to do that ourselves because in so many countries governments have increasingly become part of the problem (contributing to the restoration of decent governments is of course superimportant too; one way to do so is to join a decent political party).

A political resolution can take many forms – and no doubt there is something suitable for everyone. It can be done through volunteering. By vulnerable donations to charities that strive for social justice. By joining a political party that protects democracy and the rule of law, or organizations that stand up for human rights or other issues we still have to fight for every day. By exploring whether activism is for us and giving it a try. By starting a non-fiction bookclub and thus systematically engaging the conversation about political issues, including with people outside our own circle of friends.

My wish for 2024 would be that those who have been politically active fighting for a better world don’t give up, and that more people who so far don’t do much in terms of political contributions would join the active group. We need everyone to contribute in their role as a member of political communities. The great thing is that such political commitments, that help to make the world a little bit better (or less awful) not only can make our lives more meaningful, but also often lead to close friendships. When I was deeply involved in higher education activism (until 2022), this was one of the comments that my fellow activist Remco Breuker made (Remco is a professor of Korean studies in Leiden). Remco was right. And even the resolutions-cynic can’t argue about the importance of friendship in our lives.

My experience with geopolitics of knowledge in political philosophy so far

Geopolitics of knowledge is a fact. Only few (conservative) colleagues would contend otherwise. Ingrid Robeyns wrote an entry for this blog dealing with this problem. There, Ingrid dealt mostly with the absence of non-Anglophone colleagues in political philosophy books and journals from the Anglophone centre. I want to stress that this is not a problem of language, for there are other centres from which we, philosophers from the “Global South” working in the “Global South”, are excluded. In political philosophy, the centre is composed of the Anglophone world and three European countries: Italy, France, and Germany. From my own experience, the rest of us do not qualify as political philosophers, for we are, it seems, unable to speak in universal terms. We are, at best, providers of particular cases and data for Europeans and Anglophones to study and produce their own philosophical and universal theories. I think most of you who are reading are already familiar with the concept of epistemic extractivism, of which this phenomenon is a case. (If not, you should; in case you don’t read Spanish, there is this).

Critical political philosophy is one of the fields where the unequal distribution of epistemic authority is more striking. I say “striking” because it would seem, prima facie, that political philosophers with a critical inclination (Marxists, feminists, anti-imperialists, etc.) are people more prone to recognising injustice than people from other disciplines and tendencies. But no one lives outside a system of injustice and no one is a priori completely exempt from reproducing patterns of silencing. Not even ourselves, living and working in the “Global Southern” places of the world. Many political philosophers working and living in Latin America don’t even bother to read and cite their own colleagues. This is, to be sure, a shame, but there is a rationale behind this self-destructive practice. Latin American scholars know that their papers have even lesser chances of being sent to a reviewing process (we are usually desk-rejected) if they cite “too many” pieces in Spanish and by authors working outside of the academic centre.

In many reviews I’ve received in my career, I have been told to cite books by people from the centre just because they are trending or are being cited in the most prestigious Anglophone journals, even if they would contribute nothing to my piece and research. I have frequently been told by reviewers to give more information about the “particular” social-historical context I am writing from because readers don’t know a lot about it. This is an almost verbatim phrase from a review I got recently. I wonder if readers of Anglophone prestigious, Q1 journals stop being professional researchers the instant they start reading about José Carlos Mariátegui or Argentina’s last right-wing dictatorship. Why can’t they just do the research by themselves, why should we have to waste characters and words to educate an overeducated public? This is as tiresome as it is offensive. When I cite the work of non-Anglophone authors from outside of the imperial centres (UK, USA, Italy, Germany, and France, no matter the language they use to write), reviewers almost always demand that I include a reference to some famous native Anglophone (or Italian / German / French, without considering gender or race; the power differential here is simple geographical procedence) author who said similar things but decades after the authors I am quoting. I’ve read all your authors. Why haven’t they read “mine”? And why do they feel they have to suggest something else instead of just learning about “our” authors? This is what I want to reply to the reviewers. Of course, I don’t. I dilligently put the references they demand. I shouldn’t have to, but if I don’t, I don’t get published. There’s the imperial trick again.

English is also always a problem, but not for everyone who is not Anglophone. In 2020 I was in London doing research at LSE. I attended a lecture by a European political theorist. They gave the talk in English. Although they work at a United Statian University, their English was poor. The room was packed. The lecture was mediocre. I was annoyed. “Why do they feel they don’t have to make an effort to pronounce in an intelligible way?”, I thought. When I speak they don’t listen to me like that, with concentrated attention and making an effort to understand me. The reason is in plain view: coloniality of power. If you come from powerful European countries, you don’t need to ask for permission. You don’t need to excel. You don’t need to have something absolutely original to say. You just show up and talk. If you are from, let’s say, Argentina, and you work there (here), you have to adapt to the traditional analytic way of writing and arguing so typical in Anglophone contexts, including citing their literature, if you want to enter the room in the first place. You are not even allowed to use neologisms, although the omnipresent use of English as a lingua franca should have already made this practice at least tolerated. One cannot expect everyone to speak English and English to remain “English” all the same. Inclusion changes the game, if it doesn’t, then it is not isegoria what is going on but cultural homogenisation. (Here is a proposal for inclusive practices regarding Enlgish as a lingua franca). The manifest “Rethinking English as a lingua franca in scientific-academic contexts” offers a detailed critique of the idea and imposition of English as a lingua franca. I endorse it 100 %. (Here in Spanish, open access; here in Portuguese).

In my particular case, I am frequently invited to the academic centre, sometimes to write book chapters, encyclopaedia entries, and papers for special issues, sometimes to give talks and lectures. Not once have I not thought it was not tokenism. Maybe it is my own inferiority complex distorting my perception of reality, but we know from Frantz Fanon which is the origin of this inferiorisation.

I used to be pretty annoyed by this whole situation until I realised that I don’t need to try to enter conversations where I am not going to be heard, understood, or taken seriously. The fact is that we don’t need to be recognised as philosophers by those who willingly ignore our political philosophy. And this is why it is hard for me to participate in forums such as this blog. I just don’t want to receive the same comments I get when I send a paper to an Anglophone, Q1 journal, to put it simply.

But I also want to keep trying, not to feel accepted and to belong, but because I do believe in transnational solidarity and the collective production of emancipatory knowledge. It is a matter of recognition, and a question of whether it is possible for the coloniser to recognise the colonised, to name Fanon once more.