Academia

Images are Biased

My blogging is about two things: (1) the radical changes wrought by modern communication technology; and (2) the inability of the epistemic technologies of the written word to understand point (1).

I find this dialectical tension to be generative, but I can see how readers looking for answers might find it unsatisfying.

A recent paper in Nature, titled “Online images amplify gender bias,” makes the point in a more familiar format. Consider the first full clause of the first sentence of the abstract:

“Each year, people spend less time reading and more time viewing images”

BOOM. Footnoted: “Time spent reading. American Academy of the Arts and Sciences https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/public-life/time-spent-reading (2019).”

I’ve frequently claimed that the age of reading and writing are over, with varying forms of evidence ranging from the political, the phenomenological and the Pew Research Center. I don’t think I’ve ever convinced anyone — some people (typically young, or frequently in contact with young people) already feel it to be true, and the rest won’t change their mind after reading a blog post. This is the contradiction of points (1) and (2). And yet Guilbeault et al (2024) establishes the relevant claim as a social scientific fact of the highest order.

How is this done? The introductory section of a social science paper in Nature is an odd medium. The argumentation has to range from the expansive to the specific, and the specificity has to cover a variety of spaces within the expansive argument — all exhaustively footnoted.

If you squint, this procedure becomes absurd. The clause in the abstract becomes “the time they spend producing and viewing images continues to rise[2,4]” in the body of the text.

Footnote 2 refers to a CS paper from 2013. Footnote 4, to a technical report from something called Bond Capital, in 2019.

Is this, in fact, evidence for the claim that “the time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise”? What if this paper were to have been published in 2026? 2030?

And how does the fact that the main data analyzed in this paper were collected in August 2020 change things?

Of course, if you accept my premise (2), the literal content of the text doesn’t matter. The paper is a beautiful example of the contradiction inherent in techno-logos: we spend more time creating and consuming images, and less time producing and consuming texts. The evidence for this, recursively, does not reside in the text but in the images.

In the Flusserian framework, these are technical images. Images in fact predate texts; texts were invented because we stopped believing in images and we needed texts to explain those images. But the images in the pdf are not traditional images. Both the images under study and the statistical curves produced by the authors are technical images. These technical images are a cause and consequence of the fact that we no longer believe in text, and that we have invented technical images to explain those texts.

But let’s stay concrete! Guilbeault et al (2024) was published in Nature; what would the response be to me writing on my blog that:

“The time Americans spend producing and viewing images continues to rise. How do we know this? Zhang & Rui (2013) find that in the year 2012 there were billions of image searches conducted by Google, but in 2008, there were only a few thousand.”

The amount of evidence contained in the text is obviously insufficient to the claim — even if the information in the text is identical in the blog post and the Nature paper. The reason we believe the text in the Nature paper is because of the technical images in the pdf — these images point not to the world but to data, the true repository of knowledge today.

It bears mentioning that gender bias, the nominal focus of the paper, is a complete red herring. Obviously the argument is more compelling with an empirical demonstration, and it makes sense that the example would be something that people care about, that directly impacts their lives. But I fear that the focus on this issue obscures the argument itself.

The important part of this paper is the formal, large-scale demonstration that the mediums of text and image have different information-theoretic properties. We can try to demonstrate this empirically through small-scale experiments—indeed, I have done just this—but these demonstrations are always with respect to a given outcome, and have somehow not been convincingly synthesized. Alternatively, we can try phenomenology, to get people to experience these different mediums and reflect on this experiencing, to just THINK about what texts and images do—but that’s not scientific (Naturetific? Haha. I’m not envious at all.)

Or how about using language seriously? The claim here is that images provide more context than does text. That is, there is more extra-textual information in images than in text. What would it mean for this to be false? We literally can’t even think it false without linguistic contortion.

Another problem with the focus on the empirical case of gender discrimination is that the specifics of this case might change, but that our fundamental conclusion should not change. For example, the primary source of data for both the observational and experimental analysis is Google.

And Google is currently paying a whole lot of attention to the relationship between text, image and the representation of identity. There’s essentially zero chance you’re reading this without having heard about last week’s Gemini controversy, but just in case.

The point of this controversy is that images convey contextual information that is not present in text. This is not a problem that can be solved with RLHF fine-tuning or changing the composition of the training set; it’s a communicological fact.

It would not be (that) difficult for Google to reverse-engineer the specific analyses conducted in the Nature paper; the distribution of races and genders demonstrated for each occupation could be made to statistically match those in the Census, for example. Would this lead us to change our inference, to instead conclude that images and text contain the same amount of contextual information? No, of course not.

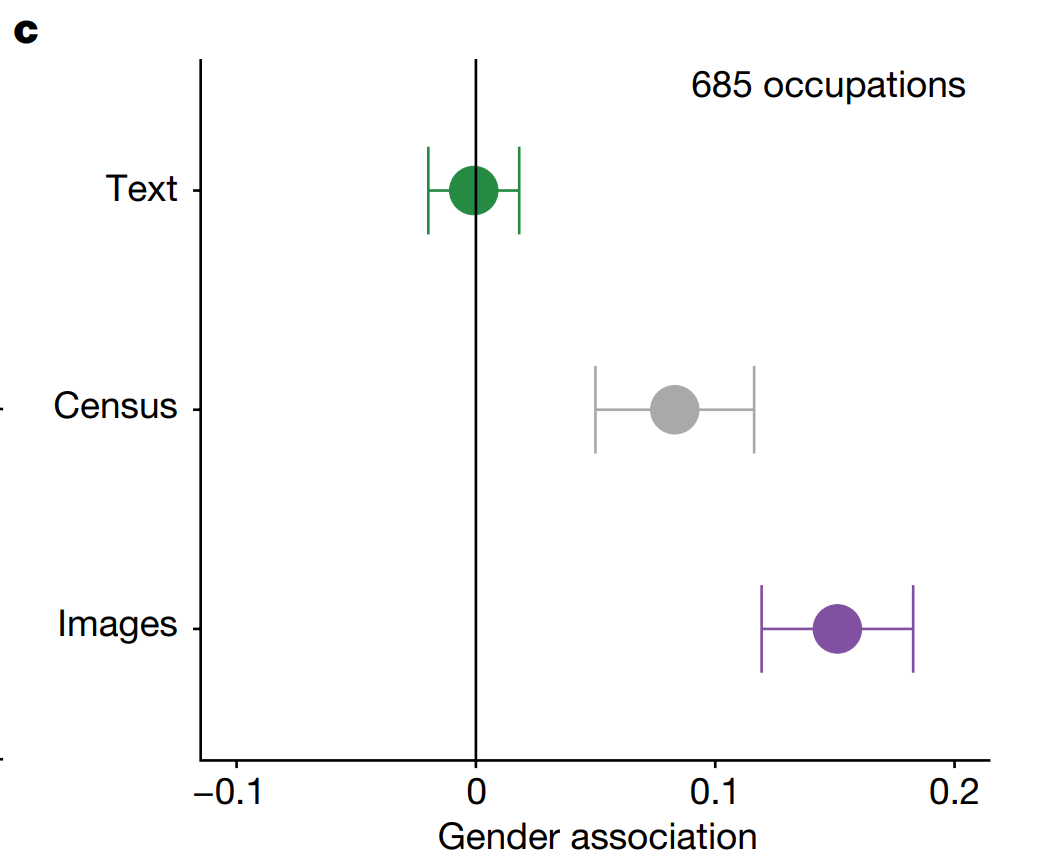

Returning to the paper, let’s ponder how Figure 2 shows that the Census has more “bias” in terms of gendered occupations than does the collection of texts. What on earth does this mean?

It means that our conception of “bias” is based on deviation from the textual, mathematical, linear, logical. This medium of communication and the associated habits of mind are very good at handling bias. But there are drawbacks. This medium is poorly equipped to communicate scale, change, and variation.

Images then necessarily introduce bias. A single image of a “philosopher” will necessarily be biased compared to the single word “philosopher.” One way in which it might be biased is gender; the word philosopher is not gendered, but most realistic images of people are gendered — not essentially or transcendently, but in practice gender is a pretty big part of self-presentation. But another way it might be biased is temporally. The word “philosopher” transcends time, but any realistic image of a philosopher would place them in time. The image would necessarily be biased compared to the word because images are better at conveying variety than at avoiding bias.

Here it become essential to understand what Flusser means by technical images as distinct from traditional images. These images “produced” by Google search or produced by Google Gemini are not images of the world; they are images of DATA. As are the images like Figure 2c above. These technical images are thus better than texts at conveying scope — and if extended to the third or fourth dimension, can be used to effectively convey dynamism as well. But just like traditional images, they are necessarily biased compared to text.

My hope, here, is to forestall a cottage industry of extending Guilbeault et al (2024) to every conceivable dimension of human communication. It is of course valuable to audit any given algorithm that has power to make decisions at societal scale — indeed I think that we are obligated to do so, and to generate time series data to see how these specific important algorithms are behaving over time — but the more fundamental point is that different modalities (“codes,” in Flusser’s framework) convey different kinds and amounts of information.

Simply by thinking about what these modalities do and tracking their empirical rise and fall in different areas of human endeavor, we can develop a much more robust understanding what information technology is doing to us — and we can decide if we’d rather it do something else.

The Crack-Up of the Michigan GOP

Some of you may have heard that the Michigan GOP is in the midst of a power struggle between Kristina Karamo, who won the party chair election in Feb. 2023, and former U.S. Representative Pete Hoekstra, who got the RNC to install him in her place her a year later after he won a contested vote. Karamo, following Trump’s principle that Republican candidates are entitled to deny the legitimacy of any election in which they are not declared the winner, has refused to concede. She has declared that she will hold a rival GOP caucus-style convention to Hoekstra’s official one, to select fake delegates to attend the national presidential nominating convention. (This is on top of the delegates that will be elected in Michigan’s presidential primary on Feb. 27.) The party has discovered that it cannot sow anti-establishment chaos to defeat its external enemies without bringing that chaos home.

There is no question that the delegates selected in Karamo’s convention will be support Trump just as much as the ones selected in Hoekstra’s. So what is the point of this conflict?

I suggest that the crisis in the Michigan GOP reveals the key cleavages within the national party, and the way its culture wars intersect with class politics on the American right. The national GOP and virtually all of its constituent state parties is fundamentally a coalition of a large portion of the business class with white Christian nationalists (WCN). Within the GOP business class, I am speaking mostly of small-to-medium business owners, especially those who have local clout–for example, auto dealers, real estate developers, and owners of restaurant franchises–plus founders and executives of big firms, especially in sectors dominated by extractive and predatory business models such as mining, fossil fuels, meatpacking, other big Ag, gambling, private prisons, firearms, defense, private equity, and multilevel marketing. (By contrast, finance, tech, health care, and entertainment present a more mixed partisan picture even at the C-suite level.) The agenda of the GOP business class is impunity. It wants freedom from accountability for the costs their business models impose on others, and from responsibility to the polity that makes their business possible, particularly when that responsibility comes in the form of taxes.

WCN are the culture warriors of the GOP, defined mainly by who they hate: immigrants, Muslims, Blacks who don’t flatter and defer to WCN, feminists, LGBTQ people, welfare-dependent poor people, people with nontraditional lifestyles, and the liberal and progressive cosmopolitans who support these groups, at least rhetorically (the “woke”). The WCN agenda is to stamp out demographic, cultural, and ideological pluralism and restore an idealized past in which they and their cultural values dominated everyone else. This is an essentially antidemocratic agenda that favors “strong” (i.e., lawless and repressive) authoritarian leaders to perform the stamping out.

The mainstream media often identifies the core Trumpist constituency with the “white working class”–i.e., white non-college voters. This interpretation makes too much of the idea that economic precarity and working-class economic grievance drives the Trump vote. Political scientists have been refuting that idea for years. Political analyst Michael Podhorzer shows that Biden split the blue-state white working class evenly with Trump and won the non-evangelicals in this group by 8 points, while losing white college voters in red states. Since the Jan. 6 insurrection, the media have rightly paid more attention to WCN as a key factor in the Trumpist wing of the GOP, which has now become virtually the entire party at the national level, having succeeded in driving out or silencing virtually everyone else. Podhorzer explains how the WCN took over the national GOP here.

There is some overlap between the GOP business class and WCN. Betsy DeVos, Trump’s Secretary of Education and a devout evangelical Christian, exemplifies the overlap. Under Trump (and before that, in Michigan politics), she pursued the WCN goal of destroying public education–a pillar of democracy and pluralism–and replacing it with for-profit charter schools, religious schools, and home schooling. Her husband Dick DeVos led Amway, perhaps the biggest multilevel marketing firm in the U.S. Her brother, Erik Prince, founded Blackwater, the defense contractor specializing in mercenary services (in both senses of “mercenary”). This mega-rich family bankrolled and practically owned the Michigan GOP for many years.

The DeVos family is unquestionably WCN, deeply religious in a bizarre synthesis of white evangelical Christianity and Ayn Randian billionaire-class impunity. But Karamo ran against the DeVos family and other “establishment” (i.e., business class) Republicans in the name of Christian nationalism. (She’s Black. But WCN’s happily support Black political figures such as Karamo, Ben Carson, and Candace Owens, who provide cover for WCN racism by endorsing their views on race-related issues and assuring them that the real racists are on the other side.) What gives?

I suggest that the conflict between Karamo and establishment WCN is what class politics looks like within the GOP. Non-college WCN despise the business-class WCN not for economic (pocketbook) reasons but for their specific brand of cultural capital: their dignified manners and superior bearing, their prissiness and contempt for vulgarity, their presumptions of working-class deference to their authority, their expertise and managerial skills. That’s their own way of looking down on the working-class WCN–not for being racist, misogynist, Islamophobic, xenophobic, and LGBTQ-phobic (since the business-class WCN shares those values)–but because they see the working-class WCN as an incompetent, ignorant, disorderly, boorish rabble. As McKay Coppins reports, Mitt Romney’s sober, Christian, dignified and superior bearing killed him in his 2016 presidential run. Trump won the nomination because, notwithstanding his billionaire wealth and his regular business strategy of ripping off working-class stiffs, he authentically embodies vulgar, boorish, disorderly behavior. He revels in it and genuinely shares the resentments of non-college WCN against anyone who acts superior to them, whether they be the “woke” left or the GOP establishment.

The trouble is, when the working-class WCN takes over a party, their lack of and contempt for managerial skills, their conspiratorial mindset, and their inability to assume personal responsibility for their failures leads to organizational failure and financial crisis. Ira Glass and Zoe Chase do brilliant and hilarious reporting of this problem of the Michigan GOP on This American Life. No wonder the establishment state GOP, led by Hoekstra, felt it needed to reassert control. It’s not clear, however, how long the GOP coalition can last on such terms. A party that depends on stoking resentment and distrust to win elections cannot count on being able to control the targets of such sentiments.

Nobody likes the present situation very much

There is a great gap between the overthrow of authority and the creation of a substitute. That gap is called liberalism: a period of drift and doubt. We are in it today.

I think that the pace of technological change is intolerable, that it denies humans the dignity of continuity, states the competence to govern, and social scientists a society about which to accumulate knowledge.

But we’ve had technological change before! some object. And things turned out fine!

Commenter Bob, for example:

I want to say, “Whoa! Have things changed so much? Are things weird?” We don’t need any explanation at all for something that hasn’t happened.

I’m sixty-nine and I’ve seen a lot of things come and go, lots of change. I can’t say that things are weirder now than they were in the past.

Yeah that’s the problem. Postwar America has been unnaturally stable, precisely for the generation who still runs things: the Baby Boomers. Tyler Cowen says that “virtually all of us have been living in a bubble “outside of history,” and on this I agree with him. “Boomer Realism”—the continued cultural power of this aging generation—papers over just how radical the changes of the past two decades (really, decade and a half) have been.

Commenter J-D takes the opposite tack:

As far as I can tell, ‘things feel weird’ is something which has been true in every period of history, because ‘things keep changing’ is something which has been true in every period of history. That’s what things do: they change.

Of course this change is different from other changes, because changes are always different from other changes.

I don’t think that a single quantitative argument could ever be dispositive here. The amount of “change” is a high-dimensional and amorphous concept, unevenly spread between people, generations, countries, and every possible demographic. If you happen to think that “things are normal”—and if you’re uninterested in the fact that other people think that “things are weird”—then I recommend you stop reading this article and go enjoy the normal world.

Acknowledging the impossibility of proving the point quantitatively, there are historical parallels which can inform how we think.

We’ve experienced “rapid technological change” before. The Industrial Revolution is often considered to be a pretty big deal, though the effects certainly weren’t felt as widely as quickly. The Second Industrial Revolution—the period from 1870 to 1914—had a much larger impact. With innovations like electrification, industrialization, mass communication, the telegraph, the railroad, oil and steel, the daily life of most Europeans and Americans became unrecognizable in two generations.

But so what happened then? Did things proceed more or less normally, except that everyone was richer, had more free time and cheaper TVs or phonographs or whatever? Did people think that things were normal?

No. That’s not what happened. This led immediately to WW1 and then the Nazis, to the Russian Revolution and then Communism. In Europe, at least, the weirdness from technological change was undeniable.

But nothing like that really happened in the United States. I’m increasingly convinced that the contemporary American historical perspective is unique in its sense of continuity, a story that goes something like this:

«Veni vidi vici — we achieved our manifest destiny, according to the plan laid out by the Founding Fathers and through the dedicated application of our spirit of self-reliance, hard work, and technological progress. We’ve got professional baseball records that go back to the 1890s, and presidential biographies that go back much farther, with no sense of a dramatic historical break. The exception, the Civil War, has been neatly historicized as the second Founding, a necessary but circumscribed effort to solve the one little issue in the Founder’s vision.»

This longer historical perspective reinforces the experience of Boomer Realism, I think; a lot of this narrative emerged specifically in the postwar era in which they were raised.

But even though the US avoided radical change, it’s useful to go back and see what the vibe was at the end of the Second Industrial Revolution. Walter Lippmann’s first major book, Drift and Mastery, provides an excellent overview.

The thesis is that the scope of the world has dramatically expanded, that this new world demands more and different things of us and of our relationships.

We are unsettled to the very roots of our being. There isn’t a human relation, whether of parent and child, husband and wife, worker and employer, that doesn’t move in a strange situation…There are no precepts to guide us, no wisdom that wasn’t made for a simpler age. We have changed our environment more quickly than we know how to change ourselves.

Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything makes the anthropological case that human society is almost infinitely variable, that are more ways of collectively organizing ourselves and of individually fitting into a collective than we can fathom, from our thoroughly modern position. But individual humans, embedded in societies inherited from the past and constrained by the mortal cycle of aging and death, are not infinitely malleable.

This, then, is my qualitative case for when things feel weird. When we change our environments faster than we can change ourselves, we are necessarily living in an alien environment. And that feels weird.

For Lippmann, this was happening for the first time. He very clearly sees 1914 as anomalous, as the culmination of dramatic changes and expansions that have pushed existing institutions to their breaking point. But he’s still, at this point, optimistic that human ingenuity will be able to rise to the task.

Indeed, what he sees as democracy’s greatest hope is an empirical, pragmatic solution, coming from the “science of administration.”

Yet it is not very helpful to insist that size is a danger, unless you can specify what size…The ideal unit may fall somewhere between? Where? That is a problem which experiments alone can decide, experiments conducted by experts in the new science of administration.

Lippmann, 110 years ago, saw this experimental democracy as the only solution to the dysfunction caused by large-scale technological, social and economic change—and was looking forward to what we would come up with.

Stafford Beer, 50 years ago, spent his career developing exactly these techniques, and desperately tried to get everyone to listen. He thought there was still time to install an architecture of effective governance, to use modern communication and computation technology to allow society to adapt as quickly as we have changed our environment.

This didn’t happen, of course. Our “ship of state” is still being steered with 18th-century technology — and it is manifestly unable to maintain any coherent bearing amidst the maelstrom of a 21st-century technological environment.

With our highest level of social organization so manifestly useless, lower units bear the strain of adaptation. Our meso-level institutions are also losing their capacity — everything from education to media to health care and housing — which in turn leaves individual people and their intimate relations as the only mechanism for adaptation.

So many of the Millennial cohortmates are desperately scrambling to hold themselves together, to grasp fragments of the social past and technological present to shore against their ruin.

Or less poetically, to accomplish enough professionally, financially, socially and romantically to achieve the once-standard goal of homeownership, marriage, parenthood and community.

Many are falling through the cracks. Gender-segregated online communities are the refuge of the miserable, and they at least provide the comfort of someone else to blame. The platforms deserve plenty of blame, but at the end of the day, Facebook is other people.

Meanwhile, at the top level, we are witnessing a multi-year car crash, watching in horror but unable to do anything to stop the octogenarian-in-chief from sailing our ship of state straight into a hideously loud, orange iceberg. The “radical new idea” proposed today by Ezra Klein is a return to the electoral institutions of the 1960s.

American culture is premised on progress. This culture has delivered, when it comes to technological progress—though far more in terms of bits than atoms, of late, and recent “AI” trends seem likely to further exacerbate this gap. But our political and social institutions have not progressed. So, we drift.

Like Beer’s insistence of designing a machine whose output is liberty, Lippmann has no patience for celebrating the simple overthrow of the past:

What nonsense it is, then, to talk of liberty as if it were a happy-go-lucky breaking of chains…the iconoclasts didn’t free us. They threw us into the water, and now we have to swim.

In a real sense it is an adventure. We have still to explore the new scale of human life which digital technology has thrust upon us. We have still to invent ways of dealing with it. Of course, people shudder and beg to be let off in order to go back to the simpler life for which they were trained. Of course, they hope that competition will automatically produce the social results they desire.

Later Lippmann will of course abandon this optimism in favor of technocratic elite governance as the only viable method for governing a country so vast, populous and dynamic. And honestly, given the information-technological constraints of the 1920s, he might have been right. But we have the internet, and cybernetics, and more compute than anyone dreamed possible. The only way to save democracy is not to reify our quill-and-parchment 18th-century institutions but to invent a 21st century democracy.

For the real Lippmann heads, here’s a bunch of fun quotes from 1914 that still struck me as relevant today.

News: We are blown hither and thither like litter before the wind. Our days are lumps of undigested experience. You have only to study what newspapers regard as news to see how we are torn and twisted by the irrelevant: in frenzy about issues that do not concern us, bored with those that do.

Clickbait: It is said that the muckrakers played for circulation, as if that proved their insincerity. But the mere fact that muckraking was what people wanted to hear is in many ways the most important revelation of the whole campaign.

Conspiracy Theories: It is possible to work yourself into a state where the world seems a conspiracy and your daily going is best with an alert and tingling sense of labyrinthine evil.

Cancel Culture: There must be some ground for this sudden outburst of candor, some ground beside a national desire for abstract truth and righteousness. These charges and counter-charges arose because the world has been altered radically, not because Americans fell in love with honesty. If we condemn what we once honored, if we brand as criminal the conventional acts of twenty years ago, it’s because we have developed new necessities and new expectations.

Urban Alienation: I might possibly treat my neighbor as myself, but in this vast modern world the greatest problem that confronts me is to find me neighbor and treat him at all. The size and intricacy which we have to deal with have done more than anything else, I imagine, to wreck the simple generalizations of our ancestors.

Left/Liberal Divide: To expect unionists then to talk with velvet language, and act with the deliberation of a college faculty is to be a tenderfoot, a victim of your class tradition.

MAGA: [Woodrow Wilson writes]: “restore our politics to their full spiritual vigor again, and our national life…to its purity, its self-respect, and its pristine strength and freedom”

Office Life: He spends his time in an office where he deals the day long with papers and telephones, the symbols and shadows of events.

The Reactionary Impulse: Though [the reactionary] remedy is, I believe, altogether academic, their diagnosis does locate the spiritual problem. We have lost authority. We are ’emancipated’ from an ordered world. We drift.

Incel-ism: Life can be swamped by sex very easily if sex is not normally satisfied.

The Implosion of the Retirement Contract

One structural source of weakness in contemporary liberal democracy is that it does not seem to be able to solve some important, even bread and butter, policy challenges. That it does not do so with the threat that global warning involves is, while highly regrettable, no mystery. It’s very difficult for democracies to take non-existing voters’ needs seriously, especially when there are powerful lobbies who have an interest they don’t. But other sources of democratic disenchantment are more puzzling.

I have in mind, especially, the accessibility of housing in popular, urban environments relative to income of younger workers, especially. I call this the “accessibility problem.” People find themselves living with their parents or with many roommates for financial reasons long after they had expected to do so. This is true in most OECD countries (see here).+

For a long time I used to think this was caused primarily by a toxic combination of rent-control, restrictive zoning laws (and building codes), mortgage deductions, and easy money by central banks (which lead to asset price inflation): all of which reduce supply and increase price of housing as population grows. Perhaps, as our very own John Quiggin suggests, lack of investment in social housing, too. Undoubtedly all of these play a contributory role. But even in places where these causes are absent or less present the accessibility problem is a hot political issue.

Somewhat, paradoxically perhaps, the root cause of the accessibility problem is itself political. For, as is well known (I warmly recommend Fischel’s Zoning Rules), in many jurisdictions local government and property-owners that are local voters have an interest in keeping land and property values high. For local governments land is directly and indirectly a major source of revenue (and among the few they control directly). And bourgeois property owners (like myself) benefit greatly from increasing property values (despite the increased taxes that follow). This is familiar enough. (They are occasions where land values and property values need not reinforce each other, but these need not concern us here.)

Depending on one’s political ideology one has a tendency to emphasize one or another of the causes listed so far. Politicians and their echo-chambers have responded by scapegoating immigrants, asylum seekers, foreign students, and (foreign) real estate speculators. All the scapegoats have been mentioned, for example, in Dutch political life during the last few years. In North America one may also hear frequently about environmental regulation and activists in this context. (In the UK about the Green Belt, etc.)

So much for set-up. What’s peculiar about all of this is that ordinary logrolling, side-payments, and deal-making should allow politicians to resolve or dissolve the accessibility problem. The fact that politicians, opinion-makers, and journalists routinely resort to scapegoating is indicative of this failure of ordinary political bargaining. It’s been nagging at me that even the most astute and impartial commentators couldn’t explain the ultimate source of the problem here. The accessibility problem is not like an intractable culture war (even if, as I suspect, the salience of a culture war my be a symptom of the intractability and intensity of the access problem).

A former PhD student, Vera Vrijmoeth (she now works at the Dutch Trade Union federation), pointed me to a better explanation. Vrijmoeth has been fascinated by the ways in which easy access to credit (or mortgages) can itself be a source of wealth inequality. In fact, as she points out the Dutch mortgage deduction (a tax-credit on mortgage interest) is usually defended by policy-makers because housing is a means to build up wealth or capital (see here [In Dutch]. The Dutch are not idiosyncratic in this sense. I return to Vrijmoeth.

Now, in recent decades we have gotten used to the idea of turning a home equity into an ATM or ‘equity extraction’ (even if that has stagnated). So, one can understand the attraction of such a policy to present home-owners (and even the general economy as the Greenspan Fed argued). But the general policy of increasing housing prices as a means to wealth predates the financial system’s ability to turn home equity into ATMs. It goes back to the core of the New Deal, and the founding of Federal National Mortgage Association or ‘Fannie Mae’ and the way it shaped and influenced the post WWII welfare states in most liberal democracies.

One of Vrijmoeth’s key insights is that a policy of ever increasing housing prices as a means to wealth increase itself generates a kind of wealth pyramid, where simultaneously entry from the bottom into the rising pyramid gets harder and harder. This is especially so when the increase in home prices outstrips productivity/wage growth as it does when supply of new homes is hindered and the prices of existing homes and land are supported indirectly through policy. I found this eye-opening because it also helps explain why the accessibility problem is so entrenched. Let me explain.

In nearly all liberal democracies, it is quite normal to treat “property” as “the ideal retirement asset for homeowners, with high house price growth helping downsizers release cash to fund their golden years.” (That’s from a Moneyweek article that is prompted by the idea that this may not last.) This is conventional wisdom in retirement planning and investment advising as any google search or (tenured) faculty party will reveal. Basically since WWII part of the implied social contract between governments and middle class citizens is that with rising prosperity, policy will allow homes to be a key means toward comfortable retirement. (Let’s call this the ‘retirement contract.’) All the policies that promote the retirement contract thereby reinforce the pyramid diagnosed by Vrijmoeth.*

In addition, the way the financial system is organized, makes middle class mortgages rather central to its health. Under the old (but still partially effective) Basel III rules, Banks were allowed to treat such mortgages as low risk and requiring very little capital buffer–this meant they were highly profitable (even if it made the banking system less resilient). To what degree Basel IV will really change this is an open question because the new rules may actually encourage more lending to borrowers deemed ‘safe.‘ Either way, the financial sector is a powerful ally of the retirement contract.

As an aside, Holland is rather unusual in one respect. It has long established and rather wealthy pension plans/schemes that cover most employees. (It’s by far the largest such system in the world per capita.) So, the Dutch can afford to speak in euphemism about the relationship between home equity and retirement.

The accessibility problem is irresolvable by ordinary political means like logrolling not just because middle-class home-owners are a formidable voting block everywhere. But primarily because there is no obvious alternative, replacement policy the government can propose to generate or create as (relatively) lush a retirement for this group as the status quo. In most countries maintaining existing public retirement schemes is already a challenge (one that closing borders to immigrants and refugees will only exacerbate). Mandatory saving for retirement is much less appealing than promoting home equity with its indirect social costs. For an ordinary politician it would be political suicide to tackle or even mention the retirement contract unless they locally represent an unusually youthful electorate.

The inability to reimagine and renegotiate the retirement contract is also why even very astute and generous commentators like Will Wilkinson, who correctly diagnose ‘NIMBY entitlement,’ don’t really get to the core of the problem. Do read his essay because it is forthright on the ways in which the status quo in American zoning practices expresses and reinforce white supremacy. (This is also true in other places, but not as well documented.) Even if it is true — let’s stipulate — that the origins and continued nature of the accessibility problem are racialist in character, diagnosing it in this fashion does not solve the ways in which the retirement contract blocks change. It’s not a winning political strategy to solve the accessibility problem.

So, on my reading of our moment in time, the accessibility problem is so entrenched that many voters are willing to give undemocratic hucksters a chance if they offer to solve it by whatever means necessary. (Recall above how scapegoating and the accessibility problem are linked in popular discussion.) I don’t mean to suggest the accessibility problem is the main source for so-called ‘democratic backsliding.’ I also don’t even mean to suggest that the voters of far right parties are primarily motivated by it.

However, on this last point it is worth investigating the following: we know that far right parties do well in aging, rural areas/regions that are ‘left behind,’ especially by young educated who have moved to the cities. We also know that these voters are often not the very poor, but the middle class there. In exploring this dynamic, social scientists have emphasized personality traits (including racist views), and educational attainment. But I wonder to what degree these are not people who are living in homes that won’t secure them the once expected, benefits of the retirement contract.++

The accessibility problem entrenches the sense of political malaise of democratic politics. Among ordinary citizens it undermines the resistance to hucksterism and gangsterism in political life, and it saps the sense of legitimacy that surrounds the politics of debate and dialogue. The fact that the rich and upper middle classes are capable of passing on their wealth means that the accessibility problem also generates a quite visible sense of unfairness about the system.** And so it is symptomatic for the crisis we’re in.

- An earlier version of this piece appeared at Digresssionsnimpressions. I thank Kirun Kumar Sankaran for discussion that led to this revised post.

+I suspect this is also connected to declining birthrates. The economist, Robert J. Barbera, pointed out to me that China has an especially perverse version of the accessibility problem combining enormous urban vacancy with high entry prices in order to maintain the fruits (?) of the housing bubble (and prevent financial implosion of connected insiders).

*Vrijmoeth’s position seems to be that the pyramid effect she is interested in is an effect of asset markets more generally (a la Piketty we might say). But on my view this is only so when policy puts effective structural floors under markets.

+I thank Joshua Preiss and John Quiggin for helping me thing about this.

**I thank John Quiggin for emphasizing this point.

Ethics Lab Yaoundé Fundraiser

One source of the Global Academic Gap is that many universities and academic resources in the Global South are underresourced (sometimes massively so). If there is no money to pay for a generator to deal with electricity blackouts, or in case there is no money to hire scholars, then it’s hard to even start doing research. And if we want to strengthen entire fields in a resource-poor country, we will also need resources for people to build the academic networks that we take so much for granted in (most) of the Global North (even when acknowledging that within the Global North there are also significant inequalities in budgets).

About 9 or 10 years ago, my institute hosted a visiting researcher – Thierry Ngosso. Thierry is from Cameroon, but did his PhD in Louvain-la-Neuve and held post-doc positions in Harvard and Sankt Gallen. For years, he tiredlessly prepared the launch of the EthicsLab in Yaoundé, now 5 years ago. Many political philosophers and ethicists from the global North and Africa met there, and discussed ethical and philosophical questions for several days. And of course, over tea-breaks and meals, we also discussed the many challanges that building an EthicsLab in Cameroon entailed.

Thierry and his friends are putting together another conference, to mark the fifth aniversary of the EthicsLab, and to strenghten the activities and networks of the EthicsLab. But they need financial support – for the conference, and for the EthicsLab more generally. It would be very ironic that they would end up with a scenario whereby there would be many more well-funded scholars from the US and Europe than from neighbouring African countries at this conference, only because of the global maldistribution of money. That’s why Thierry and his friends have started a fundraiser for the EthicsLab.

I just donated, and feel it’s a privilege to be able to make a small contribution to this fantastic initiative. Please join me in making a donation, if you are so inclined. Thank you!

Synthetic Philosophy within the division of Labor

When I first published on what I call ‘synthetic philosophy’ back in 2019, I presented the two key components of the view in such a way that it caused confusion about the position I was trying to describe as a sociological phenomenon within philosophy of science. I developed the idea of ‘synthetic philosophy’ in order to give philosophers of science a better conception of what they actually do and how this might fit in the modern university (and their grant agencies). I introduced the idea with the following characterization:

It is quite natural that my readers thought that synthetic philosophy just is a kind of integrative project. In contemporary philosophy, Philip Kitcher is (recall) the spokesperson for a view like pretty much this (including the use of ‘synthetic philosophy’) in which it is part and parcel of contemporary pragmatism. My friend, Catarina Dutilh Novaes, also advocates for a version of this view (see, for example, here at DailyNous). In Bad Beliefs, Neil Levy emphasized and developed a slightly different version of this view, too. This approach is also nicely defended by Adam Smith in the context of describing philosophy’s role in the division of labor at the start of Wealth of Nations.

My unease about this program is due to the fact that what does the integration, the integrative glue, as it were, is too unconstrained or (to use one of Timothy Williamson’s favorite words) undisciplined. I also worry that it opens the door to the image of the philosopher as creative genius who has mystical powers at understanding the totality of things. I reject the anthropological (and moral) assumption on which such a heroic figure is based. In addition — and I was myself not as clear about this back in 2019 —, hyper-specialization makes the kind of integrative project Kitcher wishes to defend a glorious, fool’s errand. (To be sure Kitcher himself is quite explicit that he rejects the anti-egalitarian commitments that are inscribed in the creative genius image.)

For, as my regular readers know (recall) Elijah Millgram’s The Great Endarkenment: Philosophy for an Age of Hyperspecialization convinced me that even within traditional disciplines it is likely that nobody has an unerring eye for detecting the objective merits of theories because of the effects of hyperspecialization and the development of local modeling languages and pidgins with their abstruse vocabulary. And so much the worse across disciplines.

That is, most of what even very well educated and curious scholars think they know about fields outside their own falls in the category of authoritated belief. (I mean by this that non-expert held believer’s endorsing or adopting the beliefs held by the relevant epistemic authorities (at a suitable level of simplification).) This makes any expertise vulnerable to impostures when they engage with others. I would argue that in Republic Plato already diagnosed this problem (recall; and here) and proposed to deal with it by organizing all of society’s institution toward breeding a caste that would be dedicated to developing the skilled exercise of practical knowledge. In a way Plato’s far-reaching (and authoritarian) proposed solution indicates how difficult this problem is.

To put this bluntly, and give you a sense of why you should take this seriously: modern academic and research grant administrators (as well as journalists, lawyers, and judges) are clueless about most of other people’s disciplines’ underlying expertise. This is why following procedure has become so important to officials in charge, and why most self-aware academic leaders sound so vacuous (and are willing to be led by PR folk) when they speak in public. It’s a sign of their intelligence that they understand they have no other choice. (‘Better to sound like a robot than an ignoramus,’ is the motto.)

As it happens, in my original article, and just a few pages later, I also added the following claim:

That is, back in 2019, for me the ‘integrative glue’’ had to be a theory or model that is in some sense capable of some generality (say, being being applicable to multiple disciplines). This would allow a kind of methodizing and disciplined approach to the synthetic aspect of the practice. I articulated the position in the context of a review of Dennett and Godfrey-Smith (and described similar features in Darwin and Rachel Carson).

Now, interestingly enough, ‘synthetic philosophy’ was coined by Herbert Spencer, without him (I think) ever defining it back in 1864. For him, it seems to cover his whole (systematic) philosophy. The Britannica usefully suggests that in Spencer philosophy itself is the synthesis of (and articulates) the fundamental principles of the special sciences. Evolution (but through acquired characteristics) plays a huge role in this project. In 2019, I adopted the phrase as a homage to Spencer, but in the safe knowledge that nobody — this is actually a standing joke about him when philosophers mention him in our age — actually reads him now. (That is a bit of a shame because (i) it means we miss what was common ground for many in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries; (ii) and while there is a kind of dull relentlessness about his project, it’s full of creative and interesting arguments.) An homage is not an endorsement of his ethical and political views.

Post Darwin, Spencer’s project clearly inspired Huxley (recall) and Peirce (recall) to use Darwinian evolution as a kind of universal acid that could explain and integrate many different phenomena not the least cosmic evolution. (This is also in Spencer, but Spencer is happier to also include arguments not out of place among seventeenth century rationalists.) The Darwinian version also constrains the arguments and modeling a bit more than it does in Spencer.

While Kitcher mentions Dewey, on my reading of his project it is, in fact, continuous with the post-Spencerian sensibility we find in Huxley and Peirce. Everyone that knows my own writing knows I am drawn to such speculative philosophers as subjects of scholarship. But such enterprises also cannot shake the aura of speculative dilettantism. In response to an earlier version of the present argument, Helen de Cruz offered a spirited defense of the philosophical dabbler like herself (see here). My view is that this stance works well for individuals, but is not a good stance for a field or a discipline to embrace.

By contrast, however, the way I understand synthetic philosophy, involves an expertise first and foremost rooted in skilled understanding or practice with theories, models, and particular (formal, computational, conceptual, etc.) methods that have a broad generality. (They need not be wholly topic neutral or universal.) The emphasis is more on the expertise and less on integration. My restatement of the position is thus:

- Synthetic philosophy is style of philosophy that presupposes or develops expertise in a general theory (or a model, a certain method/technique, etc.) that is thin and flexible enough to be applied in/to different special sciences, but rich enough that, when applied, it allows for connections to be developed among them with the aim to offer a coherent account of complex systems and connect these to a wider culture, the sciences, or other philosophical projects (or both).

That is to say, through the expertise with a modelling practice (a theory, a set of techniques) the synthetic philosopher can speak in several disciplinary languages and perhaps even generate a philosophical pidgin. Her habitat is to be found in (what Peter Gallison calls) trading zones, or arbitrage opportunities, among disciplines as well as, potentially, on the scientific research frontier, or public facing philosophy or science communication.* I have in mind philosophers who work on foundations of some formal apparatus or have the freedom to develop a theory or (say) computing into novel areas.

Now, as this account suggests I, thus, view synthetic philosopher, properly understood, as a means toward managing or coping with the problems that are the effect of hyper-specialization. Because synthetic philosophers have (ahh) feet in multiple disciplines or specializations. That is, in fact, part of their specialism. However, synthetic philosophers, while capacious in sensibility, are not to be thought of as generalists. (I am myself no synthetic philosopher.) Yes, there will always be polymaths among us. But even they are constrained by time to understand only understand a fraction.

Let me wrap up. Of course, sometimes the presence of the same formal apparatus in different fields is not illuminating. [Insert your favorite example!] I myself have a known aversion to Bayesians who use Bayes theory to hammer away at everything. Even so, I would emphasize that conceiving philosophy of science and ‘philosophy in science’ (see here Pradeu et. al.) as ‘synthetic philosophy’ is a means of disciplining professional philosophy; and of keeping philosophy salient in the modern university and to grant agencies in virtue of its potential contributions to the sciences, practical affairs, and by constituting and contributing to the manifest image. Of course, there is a risk that synthetic philosophy may not even be seen as or be housed in philosophy departments. The upside is that it’s a way of constituting the interdisciplinary potential of philosophy without just being wishy washy or tending toward escapism and that’s because permanent learning from (particular) sciences is internalized in the practice.

- An earlier version of this post was published at Digressionsnimpressions.