Academia

“The Algorithm” is the only critique of “The Algorithm” that “The Algorithm” can produce

As I say in my TED Talk about Vilem Flusser, the most pressing cultural question is: “why are things so weird?” Or as Anna Shechtman describes it:

“that feeling—floating somewhere between mania and motion sickness—that everything has changed.”

It seems like everyone really fucking wants the answer to be “The Algorithm.”

The New Yorker internet and culture columnist Kyle Chayka gives them that answer in his new book Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture.

I’ve spent years articulating why this a bad answer. “The Algorithm” is the answer that Susan Wojcicki and Mark Zuckerberg desperately want us to give. It feels like critique but it in fact reifies the premises and business models of the tech platforms: it implies that the platforms are in some computer-genius fashion holding the reins of culture and brainwashing their users. Advertisers, famously, would love to hold the reins of culture and brainwash potential customers.

And Senator, Facebook sells ads.

This is an ideological explanation for why “The Algorithm” is a bad answer. Ideological explanations are red meat for the kind of people who read Substacks, tweets, and The New Yorker, which is why I led with that. But the problem is more fundamental.

To answer the question of “why does everything feel so weird?”, it’s helpful to investigate why everyone everyone really fucking wants the answer to be “The Algorithm.”

I tackle this topic in today’s article in Mother Jones:

“The Algorithm” does not exist. Wide use of the phrase implies a false hope that there is a human who understands our dizzying information system. If it was only the algorithm on YouTube radicalizing us, or the algorithm on Facebook weaponizing misinformation, then we would know how to fix these things. We would just need regulators to pressure Mark Zuckerberg into fiddling with the parameters of some code, and things would go back to normal.

Anxieties about “The Algorithm” reveal how our lives are already governed by systems we don’t understand and can’t control. We are living with technology moving at an inhuman speed, operating at scales simultaneously smaller than we can detect and larger than anyone can comprehend.

This inversion is a powerful analytical tool. Consider: anxieties about LLMs taking the place of humans primarily reveal how society has already made humans replaceable. Only human communication which has already become routinized and rationalized is at risk of being replaced—but unfortunately, that’s most of it.

So, what is the answer? Demography doesn’t help — the generation vibe-gap has never been larger, and the institutions that should be helping us make sense of the world are still steeped in Boomer Realism. But the Sage of São Paulo has the beginnings of the answer. Rather than talk about “The Algorithm,”

media theorist Vilém Flusser has proposed we use “The Apparatus,” arguing that the emergence of new media has caused a mutation in how humans relate to each other—and to their environment. From the fullness of our physical being we are reduced to mere “operators,” experiencing primarily through the apparatus, which “programs” both the producers and consumers of media.

When we communicate via social media, we are not communicating with other people. We are communicating with The Apparatus. But it doesn’t listen. It responds—and trains us to respond back. As we accept the content presented to us, we react as if it were the product of humans rather than human-accounts; we accept our role as operators engaged in what Flusser calls “unconscious functioning.”

The content we produce and consume doesn’t mean anything because it’s not supposed to mean anything; it’s supposed to function, to cause the desired response.

The Apparatus reaches far beyond the screens through which we interact with the (powerful! nigh-ubiquitous!) algorithms that route inputs and outputs through online systems like social media. And though Flusser’s critique was developed in the context of television, social media is an intensification of the trends he identified. Social media is much more satisfactory as a proximate cause of the weirdness.

The most important technological component of social media is quantified audience feedback. Indeed, I think this is the correct definition of “social media.” It’s not a binary—media is more social the more the audience is present, the more that the media object facing the consumer is co-created by the original author and their audience. American Idol’s call-in voting thus made it more social than previous television. Twitch livestreaming chat is perhaps the most social media, conducive to connective effervescence.

The effects of quantified audience feedback have been identified in various industries. Art critic Ben Davis notes how we live in an era of “quantitative aesthetics.” Media mogul Ben Smith describes his efforts to accelerate the destruction of online news media through better audience measurement. And theorist Ben Jamin allows us to see how the quantification of attention, accreted to digital objects, creates unique value in the eye of the viewer — the modern aura not through uniqueness but through ubiquity.

The “social media” frame allows us to see how The Apparatus transforms existing communication technologies. Yelp makes restaurants more social, sure. But higher education is more social thanks to the efforts of the U.S. News & World Report. And books are more social thanks to Goodreads, sure, but this is simply an intensification of a trend that includes the New York Times Bestseller List.

Kyle Chayka’s book is still printed on dead trees. But, like, all books today, it is still more social media than books in 1800 were. The audience surrounds you even if you walk down Prince St and pick up a hard copy off the McNally Jackson Bestseller table (itself a form of social media). And one thing that operators have come to understand is that the audience loves to talk about “The Algorithm.”

The reviews of Chayka’s book clearly understand this:

Algorithms rule everything around you

Can We Free Ourselves From Algorithms?

The tyranny of the algorithm: why every coffee shop looks the same

‘Filterworld’ explores how social media algorithms ‘flatten’ our culture

How to Take Back Your Life From Algorithms

Have we all become slaves to algorithms?

This is what Flusser describes as the “circular progress” of The Apparatus. Unlike linear historical progress, which is going somewhere, this progress means an intensification of what already exists. It is the circularity of a whirlpool, tossing us around and dragging us down.

Not all of the reviews take the bait. Michelle Santiago Cortés identifies the precise point where the book goes off the rails: Chayka interviews the anthropologist Nick Seaver, who tells him that ‘the algorithm is metonymic for companies as a whole…The Facebook algorithm doesn’t exist; Facebook exists. The algorithm is a way of talking about Facebook’s decisions.’ Cortés:

However, just one sentence after Seaver’s quote, Chayka loses focus. He adds that the technology itself ‘is not at issue’, and that the cultural flattening he bemoans in the book’s title is because we’ve outgrown these algorithmic recommendations and are now ‘alienated by them.’

The pull of The Apparatus is strong; I otherwise don’t see how you can fuck it up this bad. Nick Seaver is exactly the right person to talk to, an anthropologist who has been studying the role of algorithmic recommendation for over a decade. His article on “recommender systems as traps” is a delight (seriously, read it, it’s quite accessible for an academic paper), and it identifies the crux of the problem: the switch away from metrics of recommendation quality in favor of ‘captivation metrics’ like the famous “time spent on site.” Which is the audience metric that maximizes profits.

Another review, by the incisive Anna Shechtman quoted above, nails the tone in her piece in the Yale Review:

It’s said to be quite powerful. I won’t pretend to know how it works—my understanding is that they don’t know either, which is a clever alibi. I hear that it’s a specter haunting our world. In fact, I hear that it knows that specters haunt worlds (but only at the start of an essay), which could be another way of saying that it has an uncanny grasp of cliché. It’s something like a meta-specter, really, haunting our hauntings…The Algorithm. Never has something—some agent—had such a determining force on human actions and desires, at least since the discovery of the libido or the invention of the printing press or the belief in God.

So, you get the sense that this isn’t going to go well for Chayka, that he will prove to be out of his depth, Leibniz-wise. That sense is correct. This article rules. And her conclusion nails Flusser’s conception of circular progress, though not explicitly, instead calling it “Algorithmic Culture: updating American norms, phobias, incentives, and risks—and staying the same.”

But it’s telling that even Shechtman (or her editors) chose Life in the Algorithm as the title of the review.

Cortés notes that “Chayka relies on the metonymic algorithm to step in on behalf of deeper explorations into the myriad actors, motivations and incentives.”

Or: “The Algorithm” is a metonym for The Apparatus. And it’s not an innocuous metonym, if there’s such a thing. This is the kind of linguistic sloppiness which enables analytical mistakes to propagate.

The irony of this critique is that in the book itself, Chayka’s thesis is clearly consistent with Seaver’s point that “The Algorithm” is today used to disguise the larger systems in which social media are embedded. It’s as if it has become impossible to actually read the book, to follow the through-line of the argument, to use the tools of linear conceptual reason that this media technology requires. Instead, everyone already knows what it’s about.

This isn’t a book, in the way we were raised to expect. To an ever-intensifying degree, even books are produced by and for The Apparatus. The current case makes this especially clear: Chayka wrote an essay for The Verge in 2016 about “Airspace” and the sterility of modern aesthtics. It went viral — The Apparatus demanded more. And so this book was produced.

It’s also not a book on the terms it presents itself, as deeply researched, historically-informed technology criticism. There is not a list of citations at the back, or footnotes, or endnotes. Perhaps I’m being snooty, but I have a PhD and I’m a professor who studies exactly this topic, so I’ve got to believe that all the extra work we put in on those dimensions is important. And they are! Books are an incredibly robust medium for storing and cataloguing thought—but they need a technology for pointing outside of themselves, something that has been refined over centuries. Filterworld doesn’t need that technology — because it’s more natural to use the smartphone camera instead. Like Natasha Stagg discussed on New Models, even book writing is meant to be screenshotted and to circulate on social media.

To be fair, Chayka’s website describes the book as a “reported critique,” and I guess you don’t have to cite any sources for those. But it certainly has scholarly pretensions. Chapter 1 starts with like ten pages of the history of algorithms, from Euclid to Ada Lovelace. None of this is “reported,” obviously — except in the sense of a “book report,” a homework assignment done just to check the boxes. By a clever college student, who knows how to use Wikipedia without technically plagiarizing anything.

The Wikipedia article on Algorithm is an incredible resource, both in the content and the way the knowledge is networked: from the past, with citations, and to the present, through hyperlinks to other pages. And there’s no information (that I could find) in the first pages of Chapter 1 of Filterworld that can’t be found within one click of the Wikipedia article on Algorithm.

That’s fine! Again, this is an incredibly comprehensive resource; it’d be hard to actually find something relevant and interesting for your popular nonfiction book about “The Algorithm” that wasn’t already here. But then why have this in the book at all?

Nobody gives a fuck about Robert of Chester, bro. This isn’t written to be read by humans; it’s demanded by The Apparatus, as some kind of “proof of work.” This is the kind of content that gets you from a viral essay to a viral book. But it doesn’t make any sense; it doesn’t mean anything.

Take the first section, “Early Algorithms.” Two dense pages of proper nouns that the reader has no context for, concluded abruptly by a connection to the book’s ostensible thesis: “The long arc of algorithm’s etymology shows that calculations are a product of human art and labor as much as repeatable scientific law.”

Does it show that? What if instead of the the word “algorithm,” the book were about the word “recommender system”—probably a better term for the actual technology of interest here, certainly the one that Seaver uses. Wikipedia tells us that “Elaine Rich created the first recommender system in 1979, called Grundy.”

What does the short arc of recommender systems’ etymology show? That calculations are not a product of human art and labor as much as repeatable scientific law?

Whatever. There’s no meaning here. The effect of two pages on the etymology of “algorithm” is to reify the concept, to insist that we should keep using this term, which is indeed the message of the book, as well as the message of the reviews of the book. It’s the message everyone already wanted to hear.

I’ve got further beef with how Chayka interprets my hero Stafford Beer. As encouraging as it is that the cultural tides are turning so that Beer merits almost two pages in a book like this, to summarize Beer’s critique of the misuse of computers in human organization as “As with the Mechanical Turk, the human persists within the machine” is just insulting. And the summary of the academic debate over the existence of “filter bubbles” is facile. But that’s all missing the point.

So here’s the answer for why “The Algorithm” is a popular answer now—it was a popular answer before, and the gyre of The Apparatus continues. How did this start? The Mother Jones piece explains my reasoning (please go read the whole thing!), but here’s the kicker:

The fact that we see agency in the algorithm reveals our fundamental need for interpersonal connection. It lets us imagine someone like Zuck in control of “the algorithm,” instead of adrift in “the apparatus” like the rest of us. We wish Big Brother was watching. But we might just be alone with our phones.

The Algorithm is why we’re lonely, and “The Algorithm” is because we’re lonely.

Restated, riffing on the Baudrillard quote about The Matrix:

“The Algorithm” is the only critique of “The Algorithm” that “The Algorithm” can produce.

But I think that Flusser’s answer would be less psychological and more media-theoretic, more communicological. The answer to why we feel the weirdness, that feeling somewhere between mania and motion sickness, is mirrored in the answer to why we want the answer to be “The Algorithm”:

The Apparatus has turned us into algorithms.

If generative AI is saving academics time, what are they doing with it?

Drawing on a recent survey of academic perceptions and uses of generative AI, Richard Watermeyer, Donna Lanclos and Lawrie Phipps suggest that the potential efficiency promised by these tools disclose which work is and isn’t valued in academia. Widespread use of generative AI tools in academia seems inevitable. This is one of the conclusions drawn … Continued

Sunday photoblogging: Goldfinches

I’ve been reading Maylis de Kerangal’s Réparer les vivants (oddly available in two different English translations as Heart (US) and Mending the Living (UK)), which I highly recommend. De Kerangal’s speciality is writing about people at work and this is the saga of a heart transplant over 24h, from the beginning of the donor’s day (a trip to go surfing) to the moment his heart re-starts in the recipient’s body. She gives compelling portraits of the people who work in intensive care medicine, and one of them is a nurse with a specialism in overseen the transplant and liaising with the family, who also happens to be a singer with an interest in song, including birdsong. So, there’s a passage in the book where there’s discussion of the Algerian trade in goldfinches (chardonnet in French), which, apparently, get sold for vast sums for their singing prowess. There must be something special about the Algerian ones, because the goldfinch is not an endangered species: there are lots of them out there. So, I’ve been reading about goldfinches and listening to clips of their song, and I’ve just bought a new camera lens with a reach of 800mm (full-frame equivalent) and I see birds in the distance from my living room window. I can’t really see what they are, so I pick up the lens and I see a treeful of goldfinches. And I press, through window glass. Not the greatest image, but serendipitous.

Won’t somebody think of the old people?

Continuing my discussion of the recent upsurge in pro-natalism, I want to talk about the idea that, unless birth rates rise, society will face a big problem caring for old people. In this post, I’m going to focus on aged care in the narrow sense, rather than issues like retirement income, which depend crucially on social policy.

Looking at Australian data on location of death, I found that around 30 per cent of people die in aged care, and that the mean time spent in aged care is around three years, implying an average of one year per person. Staffing requirements in Australia amount to aroundone full-time staff member per residents. So the “average” Australian requires about one full-time working year of aged care in their lifetime, or about 2.5 per cent of a working life. This is, as it happens, about the proportion of the Australian workforce currently engaged in aged care.

But what if each generation were only half the size of the preceding one? In that case, the share of the labour force required for aged care would double, to around 5 per cent.

If you find this scary, you might want to consider that children aged 0-5 require more care than old people, and for a much longer time. Because this care is provided within the family, and without any monetary return, it doesn’t appear in national accounts. But a pro-natalist policy requires that people have more children than they choose to at present. To the extent that this is achieved by subsidising the associated labour costs (for example, through publicly funded childcare), it will rapidly offset the eventual benefit in having more workers available to provide aged care.

And that’s only preschool children. There’s a significant childcare element in school education, as we saw when schools closed at the beginning of the pandemic. And school-age children still require plenty of parental care. (I’ll talk about education more generally in a later post, I hope).

Repeating myself, none of this is a problem when people choose to have children, more or less aware of the work this will involve (though, as everyone who has been through it knows, new parents are in for a big shock). But it’s clear by now that voluntary choices will produce a below-replacement birth rate. Policies aimed at changing those choices will have costs that exceed their benefits.

The JPP saga — and the way forward

This is a post that will mainly be of interest to academic political philosophers, as it concerns what happened to The Journal of Political Philosophy, and I’m assuming readers know what happened to that journal recently (if you don’t, you can read first this, and then this piece on Daily Nous).

Earlier today I attended a meeting that Wiley organised at the Eastern Philosophical Association meeting, and want to share my impression as well as share the three conclusions that I draw from this session.

The announcement was that Wiley would answer questions and talk to the community of political philosophers. But anything they said about why this happened was at such a general level and in vague formulations, that those in the room didn’t really get any new factual information. Wiley stressed repeatedly that they respected editorial independence. Wiley did say that they had underestimated the response from the community, and that they were here to listen to the community, and gather from the community ideas to how to take the journal forward.

That Wiley was there with some clear business-goals was clear, since at the end I approached a young person who had been frantically taking notes. I was assuming he was, like me, going to write up a blogpost – perhaps he was a friend of Justin Weinberg, I thought, doing a guest post for Daily Nous. When I introduced myself and asked him whether he was writing for a blog or for whom he was taking those notes, he revealed that he was a Wiley-employee.

So Wiley has its own notes on this session. Here are mine.

In essence, I understand the claims that Wiley makes as follows:

(1) Wiley needs to standardise the way they operationally proceed, because of pressures in this industry. Open Access publishers are fully standardised, Wiley has thousands of editors they are working with, and they can’t do things differently for every journal. The industry is changing and they need to adapt [to survive in the industry? To keep up profits?]

(2) On the particular case of JPP and the firing of Bob Goodin, they didn’t really say anything, except that they “couldn’t continue working with the editor and fulfil their role as a publisher”. And when they described that role, there was lots of talk about the needs of ‘operational standardization’. Apparently, even within that small room, they could not provide details. They only claimed that some things posted on the firing of Bob Goodin on social media were not true, but did not say what was or what wasn’t true. So the people in the room were left completely in the dark.

(3) They did answer the question about ownership: “Wiley is the owner of JPP, since Bob Goodin sold it to us.” I would draw from this statement the lesson that, ideally, we should find ways to own our own journals.

(4) When Annie Stiltz shared her experience with Wiley as editor of Philosophy and Public Affairs, in which she was put under pressure to publish a much larger number of papers and Wiley refused to accept her as an editor for many months, the reaction from Wiley was that they acknowledge that she had had a bad experience but that none of the people in that team where still working at Wiley. Still, to my mind no reassurance was given to why what PAPA had experienced would not happen again.

(5) Annie Stiltz also mentioned that there was pressure on the journal by Wiley to move to publishing in html. She mentioned that this might be a suitable model for the sciences, but which philosopher reads html, she asked? To this the publisher responded that “most of our readers read html” and that it was an accessibility issue. Whether that was “most of all readers, across all the sciences and humanities” or “most of the philosophers”, was not clear. It was also unclear to me whether they would want to publish html next to publishing in pdf, or replace the former with the latter (that makes a big difference, obviously).

When the floor was opened for discussion, the following things (in addition to 4 & 5 above) came up. There were more things that came up, but I couldn’t keep complete track, so hope that the other philosophers in the room can correct me if need be, and complement my reporting and impressions.

(6) Jonathan Quong, a member of the editorial board of JPP and now of the new journal Political Philosophy reminded Wiley that more than one thousand political philosophers had signed the petition in which they pledged not to submit, referee, or provide editorial services for the journal. So, he concluded, JPP doesn’t have a future. To which Wiley responded “thank you for that statement” — and that was it.

(7) Someone asked what would happen with the papers that are submitted now, given that there is no editorial team. They are received, and the authors get notified that the papers can currently not be processed. In essence, until there is a new editorial team, the papers are not being reviewed. I think under those conditions, it is unwise for anyone to submit a paper to JPP.

(8) When I asked them what they were planning to do with the journal given the boycot, they said they feel that the community would be underserved without the changes they are envisioning, and that they picked up some of the comments of the younger scholars on social media [including blogging], and that they want “to widen out the journal to new topics”. There are allegedly ongoing conversations with political philosophers. I responded that JPP should be buried.

(9) Carol Gould, editor of the Journal of Social Philosophy, then suggested that we shouldn’t ditch JPP. Instead, Wiley should change the name of the journal, to make a clear cut with JPP. She stressed that the field needs more journals. Not all good papers can get published, and young scholars need a place to publish their work.

(10) Jonathan Quong noted that Wiley mentioned repeatedly during the meeting that they are not political philosophers and that they respect academic independence. “Yet how can they then appoint a new editorial team?,” he asked. To this question, Wiley responded that they are in touch with the community, and that they are gathering advice on whom to ask for these editorial roles. No names were mentioned. There are multiple realities consistent with what they said, including that no-one is giving them useful advice. The fact that after so many months since the announcement that Goodin would be fired they still do not have an editor, doesn’t bode well.

I came away with three thoughts on this.

First, this was a meeting Wiley set up to limit the damage. I doubt, though, that anyone in the room who signed the petition, has changed their mind. If anyone did, please do let us know in the comments section. Wiley did not give any details that could help me change my mind. All Wiley had said could have been preceded by the sentence: “Because of our mission to increase our profits”, …. we need to standardise our procedures / increase the number of papers we publish / work with editors who do what we ask them / want to talk to political philosophers to improve our image etc. etc. One may arguably object that I’m being a bit cynical here, but then I am a scholar of capitalism and Wiley is above all a capitalist enterprise.

Second, we, political philosophers, need to talk amongst us what we need in terms of journals to serve the needs of all political philosophers, including political philosophers who currently don’t get their papers published because acceptance rates are so low. Are the acceptation rates too low? Do we need more journals? Do we need to expand the current journals?

Third, we, political philosophers, also need to talk about good practices. Carol Gould suggested that journals should adhere to the APA’s guidelines on good publishing practice, which includes the strong recommendation of triple blind anonymous review. JPP didn’t have that, and its “true successor” Political Philosophy doesn’t have that either. There are also concerns that it’s really hard to publish on some topics in political philosophy in the journals that we have, such as nonwestern political philosophy.

I strongly support the solidarity of political philosophers against Wiley’s top-down decision making, which I still consider a violation of academic autonomy. I have not heard anything in this session to make me change my mind. But the attack on JPP also brought out more in the open some voices who are worried about how the field of political philosophy journals looks like. In the context of a journal under attack, it is understandable that we don’t want to conflate these two discussions. Whatever criticism one might have on the old JPP, we must not let that be used as ammunition by Wiley to let them get away with what they did.

So what then should we do? We, political philosophers, should take control over our future. We should not contribute to the revival of JPP, so that it is clear to Wiley and any other publisher what we do not tolerate. But we should also have a discussion, outside the sessions organised by publishers trying to do damage controle, what we need in terms of journals – whether we have enough journals, whether their practices can be improved, and whether they are sufficiently pluralistic in terms of methods, traditions and topics. And that conversation can’t just take place at the APA, since journals are international, and political philosophers are spread over the globe. In order to make it accessible to all, perhaps it is a conversation we can have on blogs?

The Hayakawa Question

I love writing. The medium is excellent for communicating ideas, or a narrative history. But writing is one-dimensional, and it’s much worse at communicating the history of ideas in higher dimensions.

My meta-scientific interest in understanding how ideas travel, how their fate waxes and wanes, has frequently pushed me beyond my preferred medium. Traditional historiography is extremely time-consuming: you have to read and compare various histories of the same topic over time and across perspectives.

An inductive, data-driven approach won’t provide any conclusive results — but it might tell us where we should look. My goal is to find ideas that at one point seemed promising—perhaps, with modern technology, we can explore branches of human development that were prematurely or arbitrarily cut off. The cybernetic socialism of Stafford Beer is one of my favorite such examples; what else can we find?

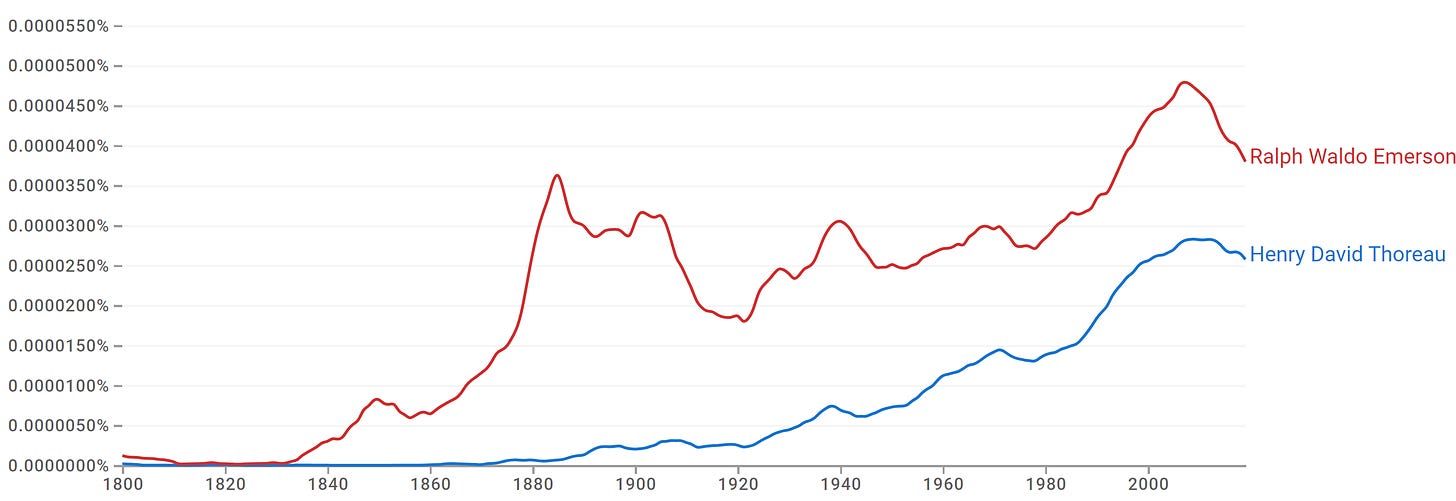

Every American high schooler learns about the twin giants of Transcendentalism: Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The two most famous members of the Transcendentalist Club, with contrasting vibes, make for a neat narrative. But the data tell a different story.

Emerson has long been an important figure in the history of ideas, but nobody gave a fuck about Thoreau for decades after his death. Poking around a bit, my take is that his anti-war sentiment caused an uptick in interest in the 1940s, and then again in the 1960s and 70s, when the hippies found broader resonance with his more poetic writing. The subsequent elevation is precisely the consequence of the narrative crafted for the high school US History class that prompted me to think of this comparison in the first place. And then there’s the worst fanfic of all time, Walden Two, on which more, later.

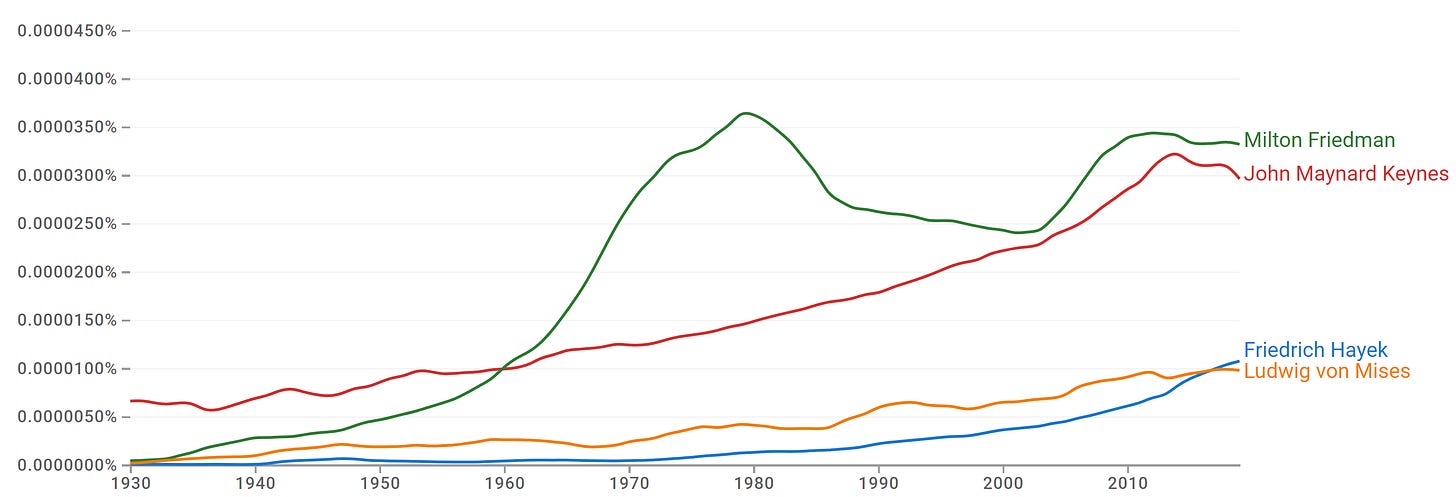

Another example, from Economics. The major axis of debate over the past century has been between the pro-market and pro-state intervention camps, and their respective champions Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes. Except that…Hayek was an inside job.

Nobody was talking about him (in the English-language books indexed by Google Ngrams) until the 1970s, and there has been a noted slope change in interest in the 2010s. Fellow free-marketer Milton Friedman has always been more important, and even fellow Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises had more coverage until very recently.

Proper nouns like this are a powerful historiographical tool because they’re fixed. Concepts like “democracy” or “feminism” are far less amenable to this method because their meaning shifts over time. We don’t really care about the words except insofar as they refer to the same underlying idea. But proper nouns point to the same person; especially after they die, their referent is fixed, and we can learn about the intellectual context by looking at trends in their use.

Haha. If only it were that simple.

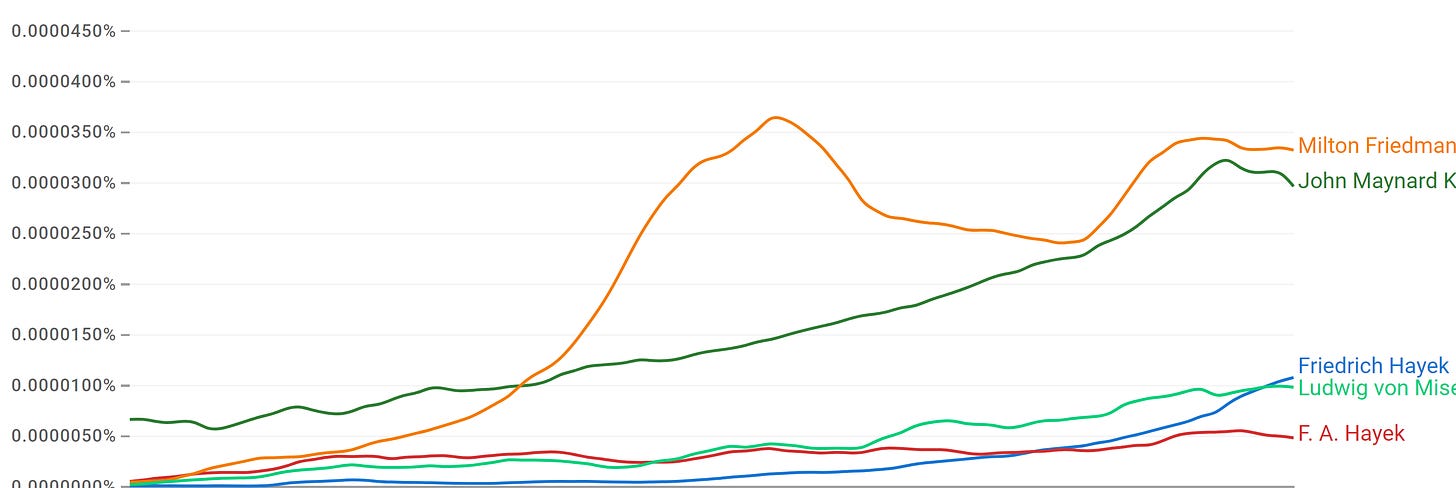

In his lifetime, the anglophile Hayek more often went by “F. A. Hayek” rather than his Germanic given name, which complicates the data-historiographical story. Hayek was important, especially in the 1940s and 50s after publishing The Road to Serfdom. Adding the two lines together makes his case look more like Keynes’, though the sharp uptick over the past decade is still striking.

The Hayek example also casts doubt on the data-historiographical method. I had the contextual knowledge to check for this — a purely machine-driven approach would have a much more difficult time matching these records. The Google Ngrams interface is especially finicky, so I’d take any of these results as preliminary.

(Methodological aside: this problem calls out for some heavy inductive machine learning. Large, comprehensive datasets like the Ngrams corpus or longitudinal surveys like the Census’ American Communities Survey and the political scientists’ American National Election Survey would benefit tremendously from this kind of pre-processing. Current practice entails taking the dataset as given and asking each researcher to preform their own ad hoc data manipulations, a recipe for duplicated efforts, false positives and outright error.)

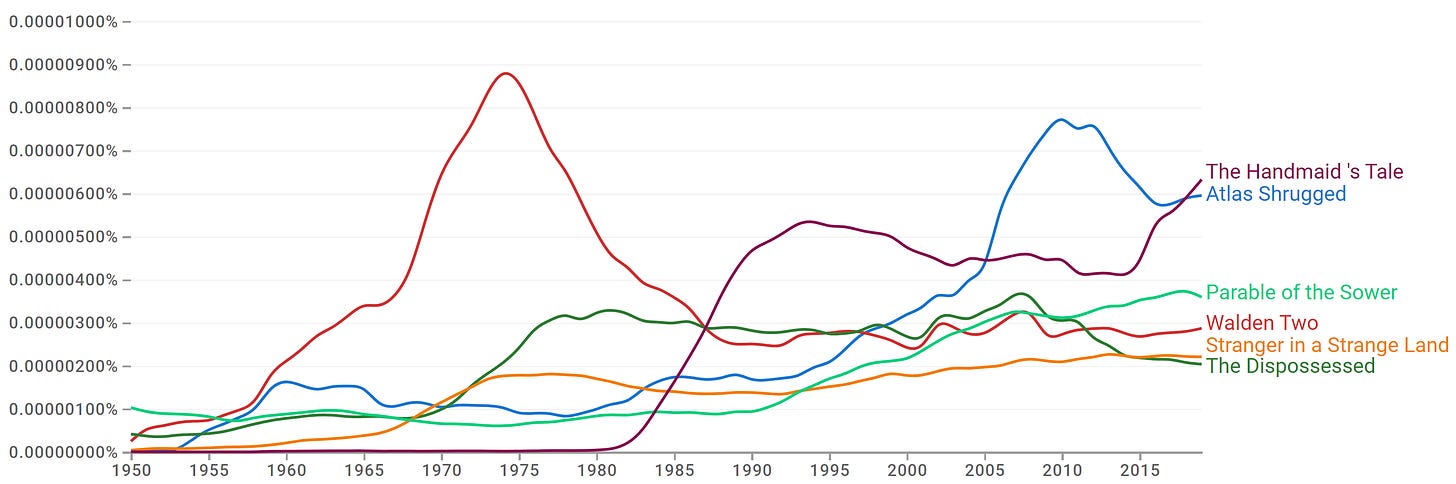

An even more fixed kind of proper noun is that reinforced by copyright law. For intellectual history, the best example is the book. Science fiction is an excellent resource for understanding a society’s fantasies and fears, its vision of possible futures. Or, in the case of Atlas Shrugged, its vision of possible futures foregone.

The Randian masterpiece exploded in popularity in the early 200s, and has since fallen off. The Dispossessed, Ursula Leguin’s ambivalent socialist novel, held steady for four decades before seeing a recent decline in interest. In contrast, Parable of the Sower and The Handmaid’s Tale have seen gradual and sharp growth, respectively. (These two examples also complicate the proper noun story. The former is, of course, named after a parable that appears in the Gospels; the latter recently became a television series.)

The real story here is Walden Two, which in 1975 was more popular than Atlas Shrugged ever was, but which few people today have heard of. This is just as well. This book sucks ass. I picked up a used copy, read it, and then physically destroyed it, I was so upset.

The vision is of scientific fascism, presented as utopia. Ivan Illich, in a book from the same period, refers to the end point of industrial society as “BF Skinner’s worldwide concentration camp.” Strong words, but given the popularity of the book, I understand the urgency. The threat of behavioralism is still with us.

And that’s just the ideas. The prose in Walden Two is laughable. Anyone who has ever called Ayn Rand a hack needs to read literally any chapter of this book and apologize. In the novel, the psychologist-king of the titular commune (an obvious Skinner stand-in) sounds like a dumb pigeon’s idea of a smart person.

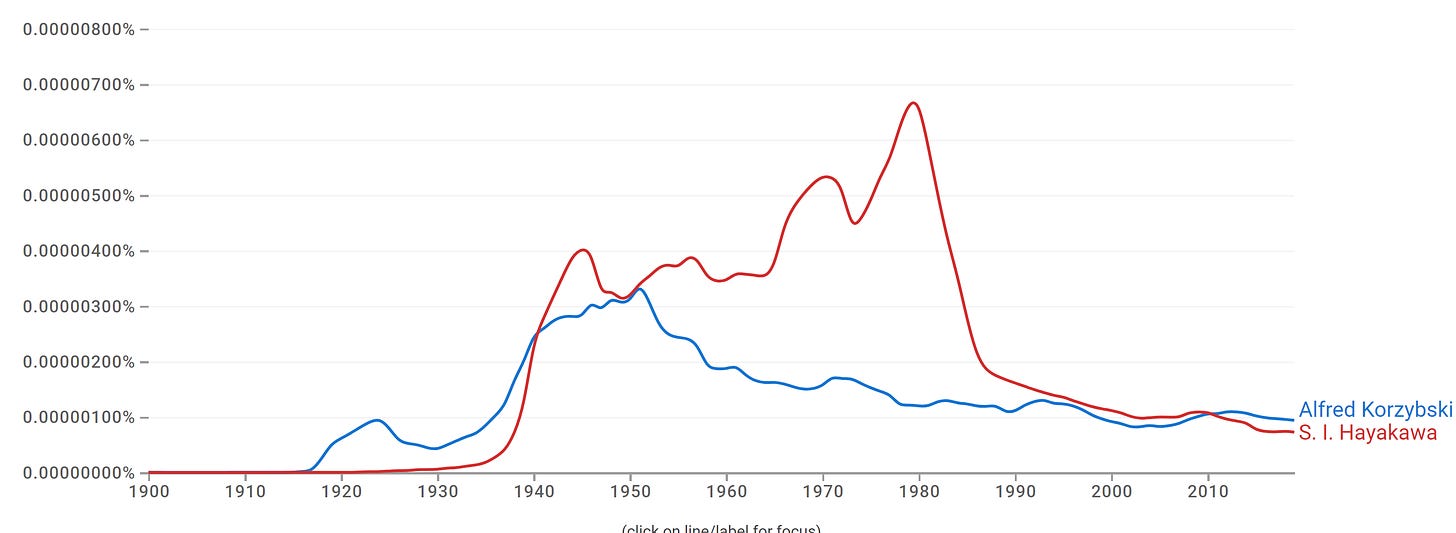

My point, other than just needing to vent, is that some of the “forgotten ideas” are really better off in the dustbin of history. No amount of data can distinguish Walden Two from, say, the General Semantics of Korzybski and Hayakawa. Many of my favorite thinkers from this period mention this movement, but I can’t make heads or tails of it.

The stark red cliff serves as an inspiration for what I’m calling the Hayakawa Question:

Which thinkers have experienced the most dramatic rise and fall in intellectual influence?

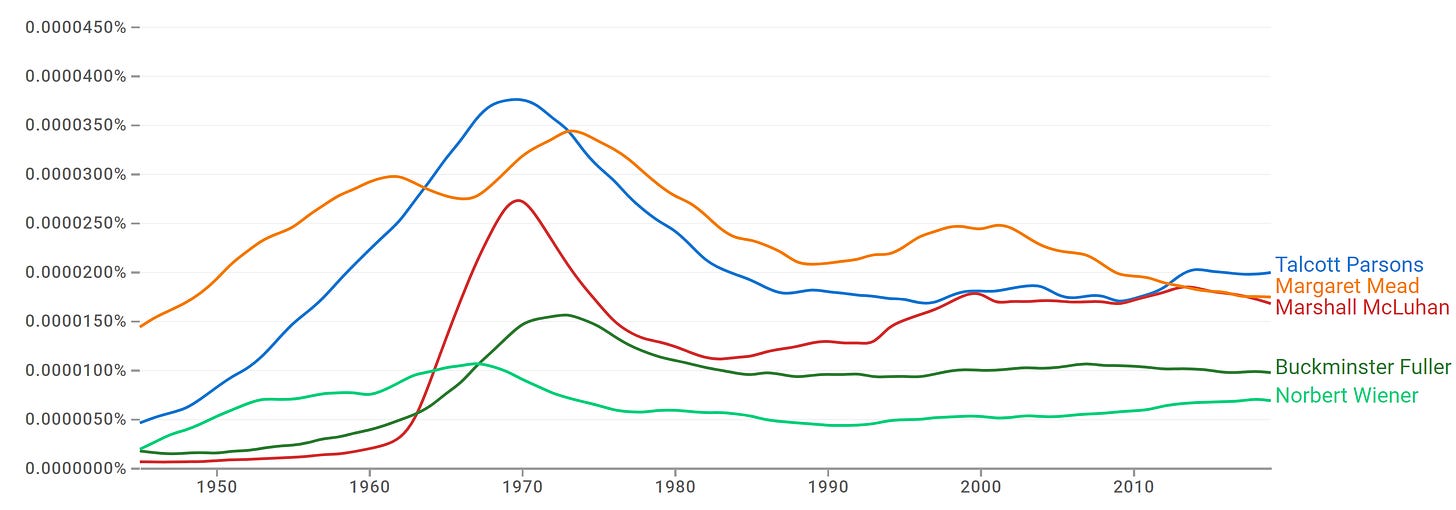

Most immediately relevant for my intellectual project is identifying the thinkers who took advantage of the postwar scientific revolution but who have fallen out of contemporary favor. I started with some of my recent favorites, all of whom were in some way associated with or inspired by cybernetics: Marshall McLuhan, Margaret Mead, Norbert Wiener, and ol Bucky Fuller.

McLuhan’s ascendence and decline was steepest, but recent years have seen a re-appreciation for his work. Mead is the only one still in decline, despite being the most cited for most of the time series…the whole time, really, other than the reign of some dude called Talcott Parsons (???), who a sociologist friend suggested as a plausible candidate for a rapid decline in influence.

The fact that I’d never heard of Parsons is weak evidence of his obscurity; that’s the value of this approach. It turns out that, yes, Parsons is well-known in Sociology…he co-founded the Harvard Sociology department in 1930.

The Parsons example provides further evidence for my theory: he, too, was heavily influenced by cybernetics, was in some ways at the center of it. Another thinker for me to chase down…if you have further suggestions, they’d be very welcome!.

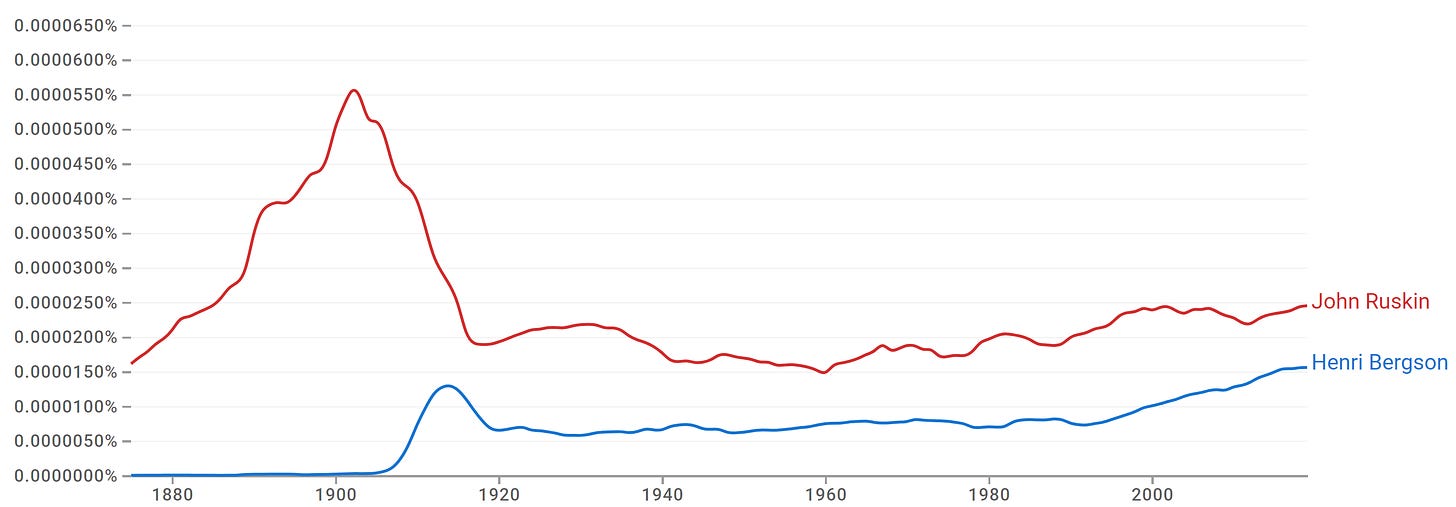

A bit further back in history, I’ve found what I think is the most dramatic decline of any thinker, my current answer to the Hayakawa Question: British polymath and Christian socialist John Ruskin. Another pattern of interest, with a roller-coaster start whose peak has only recently been surpassed, is Henri Bergson, who I think is the key link between the American pragmatists, postwar cybernetics, and the post-structuralist/Marxist tradition.

Google Ngrams cannot serve as the only evidence for the Hayakawa Question. The methodological issues remain: even proper nouns, the most tightly fixed relationship between language and the world, still drift. Though Hayakawa began his career as a semanticist and student of the enigmatic (to me) Korzybski, things took a dramatic turn when he randomly became the Republican Senator from California in 1976.

Wikipedia recounts how he won the Republican primary over “three better-known career politicians,” but was expected to get trounced in the general so badly that his incumbent opponent didn’t even campaign…but then Watergate happened and his status as a political outsider played well enough for him to win. He was apparently so bad at politics that—despite being a sitting Senator—he was unable to get his shit together and didn’t even have the money to run in the primary. “Hayakawa was news media reporters’ favorite fodder, as he was often found napping through important legislative voting.”

Again, I have no context for any of that. But it does explain why, in 1982, his Google Ngrams score falls off a cliff. It doesn’t have anything to do with the interest in his theory of semantics.

I did learn one thing about his mentor Korzybski, though: he coined the phrase “the map is not the territory.”

Ready for American readers!

I should have posted this much earlier, but it just dawned on me that I should have invited all our NYC-based readers to the book launch of the US-edition of my book on Limitarianism. I guess my best and most truthful excuse is that I’ve been too busy with media requests since the Dutch version of my book came out at the end of November. Especially in Belgium, where I was on the main talkshow on TV, the idea that we should limit how much personal wealth each of us can have, has led to a lot of debate (in fact, the same talkshow scheduled limitarianism again as a topic for debate among some politicians the next day, as apparently they had seldomly received so many reactions but also questions from their viewers). There are a few interviews lined up with American and international media – I’ll post links to some of it in due course for anyone interested.

I should have posted this much earlier, but it just dawned on me that I should have invited all our NYC-based readers to the book launch of the US-edition of my book on Limitarianism. I guess my best and most truthful excuse is that I’ve been too busy with media requests since the Dutch version of my book came out at the end of November. Especially in Belgium, where I was on the main talkshow on TV, the idea that we should limit how much personal wealth each of us can have, has led to a lot of debate (in fact, the same talkshow scheduled limitarianism again as a topic for debate among some politicians the next day, as apparently they had seldomly received so many reactions but also questions from their viewers). There are a few interviews lined up with American and international media – I’ll post links to some of it in due course for anyone interested.

I am in NYC right now in the first place because the program committee of the American Philosophical Association was so kind to invite me to give a scholarly paper on limitarianism. But since I was going to be here, and since we all have to minimize flying if we can (or at least: not fly without thinking twice or three times), my American publisher decided to also organise the book launch this week. That will take place tomorrow/today/yesterday (delete depending on when you read this post) – Tuesday January 16th, 6 pm, at Rizzoli Bookstore, 1133 Broadway. I will be interviewed by Daniel Wortel-London, a policy advisor at the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy. If you attend, please say hi – I’ve always been wondering who our readers are.

I would also like to use the occasion to thank the amazing thinkers and activist millionaires – including Thomas Piketty, Abigail Disney, Marlene Engelhorn, Kate Raworth, our own John Quiggin and several others – who wrote nice things for the cover and the website of the book (click on ‘praise’ on the book’s webpage). I am really humbled by their support.

For anyone based on London, there will be a book launch event for the UK-edition (which has a very different cover) on January 31st at the London School of Economics and Political Sciences.

Mute inglorious Miltons

Chris’s post on declining population has prompted me to get started on what I plan, in the end, to be a lengthy critique of the pro-natalist position that dominates public debate at the moment. My initial motivation to do this reflected long-standing concerns about human impacts on the environment but I don’t have any particular expertise on that topic, or anything new to say. Instead, I want to address the economic and social issues, making the case that a move to a below-replacement fertility rate is both inevitable and desirable.

I’m going to start with a claim that came up in discussion here and is raised pretty often. The claim is that the more children are born, the greater the chance that some of them will be Mozarts, Einsteins, or Mandelas who will contribute greatly to human advancement. My response was pre-figured several hundred years ago by Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. Gray reflects that those buried in the churchyard may include some “mute inglorious Milton” whose poetic genius was never given the chance to flower because of poverty and unremitting labour

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne’er unroll;

Chill Penury repress’d their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Billions of people alive today (the majority of whom are women) are in the same situation today, with their potential unrealised through lack of access to education and resources to express themselves. Rather than adding to their numbers, or diverting yet more resources away from them, we ought to be focusing on making a world where everyone has a chance to be a great poet or inventor.

Foreshadowing future argument

The political difficulties of achieving the necessary redistribution are immense. We are unlike to achieve even the basic targets set out in the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. But even supposing that the world were a fairer place, it is unlikely that we can provide the kind of education necessary for full participation in a modern economy while having more than two children each (that is, more than one child per parent) on average. The fact that fertility rates in all development countries are below this level is a reflection of economic reality, not the product of social decadence. I’ll be expanding on this point a lot, so I’d welcome it if the discussion focused on the main part of the post.