Soviet Union

Homelands: A Personal History of Europe – review

In Homelands: A Personal History of Europe, Timothy Garton Ash reflects on European history and political transformation from the mid-20th century to the present. Deftly interweaving analysis with personal narratives, Garton Ash offers a compelling exploration of recent European history and how its lessons can help us navigate today’s challenges, writes Mario Clemens.

Homelands: A Personal History of Europe. Timothy Garton Ash. The Bodley Head. 2023.

Almost ten years ago, I heard the then-German Foreign Minister (and current Federal President) Frank-Walter Steinmeier say that we have to prepare ourselves for the fact that in the near future, crises will become the norm. What sounded like a somewhat eccentric assessment now appears to be an apt description of our reality, including in Europe. How did we get here?

Almost ten years ago, I heard the then-German Foreign Minister (and current Federal President) Frank-Walter Steinmeier say that we have to prepare ourselves for the fact that in the near future, crises will become the norm. What sounded like a somewhat eccentric assessment now appears to be an apt description of our reality, including in Europe. How did we get here?

As Timothy Garton Ash argues in Homelands: A Personal History of Europe, Western Liberals made the mistake of relying on the unfounded assumption that history would simply continue to go their way. Post-cold-war-liberals failed, for example, to care enough about economic equality (237) and thus allowed Liberalism to make way for its ugly twin, Neoliberalism.

Western Liberals made the mistake of relying on the unfounded assumption that history would simply continue to go their way.

Whether we want to understand Islamist Terrorism, the rise of European right-wing populism, or Russia’s revanchist turn, in each case we find helpful hints in recent European history. What makes Garton Ash the ideal guide through the “history of the present” is his three-dimensional experience: that of a historian, a widely travelled and prominent journalist and a politically active intellectual.

What makes Garton Ash the ideal guide through the “history of the present” is his three-dimensional experience: that of a historian, a widely travelled and prominent journalist and a politically active intellectual.

Garton Ash started travelling across Europe fresh out of school, “working on a converted troopship, the SS Nevada, carrying British schoolchildren around the Mediterranean” (27). Aged 18, he was already keeping a journal on what he saw, heard and read.

He nurtured that journalistic impulse and soon merged it with a more active political one, eventually becoming the “engaged observer” (Raymond Aron) that he desired to be. In the early 1980s, he sat with workers and intellectuals in the Gdańsk Shipyard, where the Polish Solidarity movement (Solidarność) emerged. Later in the 1980s, he befriended Václav Havel, the Czech intellectual dissident and eventual President. Garton Ash chronicled and participated in the movement led by Havel, which successfully achieved the peaceful transition of Czechoslovakia from one-party communist rule to democracy. Since then, Garton Ash has consistently enjoyed privileged access to key political figures, such as Helmut Kohl, Madeleine Albright, Tony Blair and Aung San Suu Kyi. Simultaneously, he has maintained contact with so-called ordinary people. All the while, he has preserved the necessary distance intellectuals require to do their job, which in his view “is to seek the truth, and to speak truth to power” (173). His training as a historian, provides him with a broader perspective, which, in Homelands, allows him to arrange individual scenes and observations into an encompassing, convincing narrative.

Garton Ash has published several books focusing on particular themes, such as free speech, and events, such as the peaceful revolutions of 1989. In addition, he has published two books containing collected articles that cover a decade each. History of the Present: Essays, Sketches, and Dispatches from Europe in the 1990s and Facts are Subversive: Political Writing from a Decade without a Name, which covers the timespan between 2000 and 2010. Homelands now not only covers a larger timespan, the “overlapping timeframes of post-war and post-wall” (xi) – 1945 and 1989 to the present – but the chapters are also more tightly linked as had been possible in books that were based on previous publications.

By the second decade of the twenty-first century we had, for the first time ever, a generation of Europeans who had known nothing but a peaceful, free Europe consisting mainly of liberal democracies.

“Freedom and Europe” says Garton Ash, are “the two political causes closest to my heart” (xi), and he had the good fortune to witness a period where freedom was expanding within Europe. Now that history seems to be running in reverse gear, he worries that this new generation don’t quite realise what’s at stake: “By the second decade of the twenty-first century we had, for the first time ever, a generation of Europeans who had known nothing but a peaceful, free Europe consisting mainly of liberal democracies. Unsurprisingly, they tend to take it for granted’ (23-24).

Thus, one critical aim motivating Homelands is to convey to a younger generation what has been achieved by the “Europe-builders,” men and women who have been motivated by what Garton Ash calls the “memory machine,” the vivid memory of the hell Europe had turned itself into during its modern-day Thirty Years War (21-22). While nothing can equal this “direct personal memory,” he argues that there are other ways “in which knowledge of things past can be transmitted” – via literature, for instance, but also through history (24), especially when written well.

A gifted stylist, Garton Ash makes history come alive by telling the stories of individuals

A gifted stylist, Garton Ash makes history come alive by telling the stories of individuals, for instance, that of his East German friend, the pastor Werner Krätschell. On Thursday evening, 9 November 1989, Werner had just come home from the evening church service in East Berlin. When his elder daughter Tanja and her friend Astrid confirmed the rumour that the frontier to West Berlin was apparently open, Werner decided to see for himself. Taking Tanja and Astrid with him, he drove to the border crossing at Bornholmer Strasse. Like in a trance, he saw the frontier guard opening the first barrier. Next, he got a stamp on his passport – “invalid”. “‘But I can come back?’ – ‘No, you have to emigrate and are not allowed to re-enter,’” the border guard replied. Horrified because his two younger children were sleeping in the vicarage, “Werner did a U-turn inside the frontier crossing and prepared to head home. Then he heard another frontier guard tell a colleague that the order had changed: ‘They’re allowed back.’ So he did another U-turn, to point his yellow Wartburg again towards the West” (146).

History, written in this way, “as experienced by individual people and exemplified by their stories” (xiii), may indeed help us to “learn from the past without having to go through it all again ourselves” (24).

Though he emphasises the wealth, freedom and peace in late 20th-century Europe, Garton Ash also reminds us that post-war European history, even its “post-wall” period, is not an unqualified success story.

Though he emphasises the wealth, freedom and peace in late 20th-century Europe, Garton Ash also reminds us that post-war European history, even its “post-wall” period, is not an unqualified success story. Notably, right after the Cold War, there were the hot wars accompanying the dissolution of Yugoslavia. He regards the fact that the rest of Europe “permitted this ten-year return to hell” as “a terrible stain on what was otherwise one of the most hopeful periods of European history” (187).

Garton Ash is equally alert to the danger of letting one’s enthusiasm for Europe’s post-war achievements turn into self-righteousness. “That post-war Europe abjured and abhorred war would have been surprising news to the many parts of the world, from Vietnam to Kenya and Angola to Algeria, where European states continued to fight brutal wars in an attempt to hang on to their colonies” (327).

While such warnings qualify and differentiate Homelands’ central message – that today’s Europeans have much to lose – they do not reverse it. But knowing that one is bound to lose a lot can also have a paralysing effect, as many of my generation currently experience. Here again, history can help: to understand our present, we need to know what brought us here. Garton Ash is convinced that we can learn from history; he, for instance, claims that the rest of Europe should “learn the lessons of Brexit” (279).

Those who seek orientation through a better understanding of the past should turn to this extraordinary, eminently readable exploration of recent European history.

Homelands: A Personal History of Europe perfectly complements Tony Judt’s extensive Postwar (published in 2005). While Judt’s work offers a detailed and systematic account of European history after 1945, Garton Ash’s book seamlessly blends personal narratives, insightful analysis, and astute critique. Those who seek orientation through a better understanding of the past should turn to this extraordinary, eminently readable exploration of recent European history.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: struvictory on Shutterstock.

The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World – review

In The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World, Tim Marshall analyses the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. According to Gary Wilson, the book is an illuminating insight into the political geography of space and the dynamics between world powers as they continue to expand the space frontier.

The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World. Tim Marshall. Elliott & Thompson. 2023.

While Tim Marshall’s previous works have firmly established him as a prominent authority on the politics of geography, in this new book he enters uncharted territory: an appraisal of the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. In a series of earlier books Marshall considered the impact of geography on the possibilities and limitations of the projection of national power in some of the world’s political hotspots. The Future of Geography breaks new ground by probing how major world powers’ activities in space may come to shape the future of world politics in (until recently) ways which could not have been envisaged.

While Tim Marshall’s previous works have firmly established him as a prominent authority on the politics of geography, in this new book he enters uncharted territory: an appraisal of the geopolitical dynamics and consequences of space exploration. In a series of earlier books Marshall considered the impact of geography on the possibilities and limitations of the projection of national power in some of the world’s political hotspots. The Future of Geography breaks new ground by probing how major world powers’ activities in space may come to shape the future of world politics in (until recently) ways which could not have been envisaged.

The Future of Geography begins with the premise that space is rapidly becoming an extension of earth, representing the latest arena for intense human competition. Although the book explores the space activities and objectives of a wide spectrum of states and other actors, Marshall makes clear from the outset that there are three main players to be aware of: China, the US and Russia.

Space is rapidly becoming an extension of earth, representing the latest arena for intense human competition.

The book is structured into three parts. The first of these is relatively brief and consists of two chapters which serve to provide useful context for the more substantive treatment of space activity found in part two. In chapter one Marshall traces interest in space back to the earliest recorded historical periods, noting that there is a long history of “studying stars,” stone circles and similar (phenomena perceived as otherworldly or mysterious). Beginning with the Babylonians, he charts astronomical advances through Greek and Roman times into the twentieth century, referencing the scientific contributions of the likes of Copernicus, Galileo and Newton along the way. In the second chapter, Marshall identifies the origins of modern space exploration in Germany’s wartime rocket development programme, before proceeding to explain the importance of the Cold War in generating further advances in space as part of the arms race between the US and the Soviet Union. A string of Soviet “firsts” in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminated in Yuri Gagarin being the first man in space, which lead to huge surges in American space budgets as they raced to put the first man on the moon.

A string of Soviet “firsts” in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminated in Yuri Gagarin being the first man in space, which lead to huge surges in American space budgets as they raced to put the first man on the moon.

Part Two of the book represents its substantive core. In its six chapters, Marshall first explores some of the general difficulties and tensions generated by modern space exploration, before appraising the space policies of the world’s major players in this arena. The geography of space cannot be understood in earthly terms and scales, but in chapter three Marshall presents a series of numerical markers which permit the reader to gain some sense of the enormity of distances in space. Although NASA regards space as beginning at 80 km, the International Space Station is located 400km into space, while medium and higher earth orbit extend the area for potential exploration yet further. Noting that over 80 countries have satellites in space, Marshall posits that “the idea that space is a global common is disappearing.”

Most existing international space treaties are regarded as outdated, products of the Cold War that fail to account for technological advances and the expansion of states with space-related aspirations.

This leads into chapter four’s consideration of efforts to regulate space by legal mechanisms. Most existing international space treaties are regarded as outdated, products of the Cold War that fail to account for technological advances and the expansion of states with space-related aspirations. At best, current space activity is governed by a series of non-binding, ad hoc agreements. Marshall lays out the various sources of potential scope for conflict or disagreement, including questions raised by the activities of private bodies in space and increased space debris from the deployment and destruction of satellites. While the need for new legal regimes to regulate and foster cooperation in space activity is accepted, such developments are hindered by the fact that the major three space powers agree on little.

China’s space programme is more militarised than the others and, despite being a slower starter in space exploration, now seeks to rival the International Space Station.

The following three chapters consider in turn the space policies of the three big space powers. China’s space programme is more militarised than the others and, despite being a slower starter in space exploration, now seeks to rival the International Space Station. It is the only country operating its own space station and is working with Russia on the creation of moon base. China established various “firsts” in space during the first decades of the twenty-first century, is home to over a hundred private space companies and has developed plans for the years ahead, including launching over 1,000 satellites within a decade. Within the US, space investment has fluctuated over time in accordance with its relative popularity. However, in 2019 the US launched a 16,000 strong Space Force and has invested heavily in early-warning satellites and laser weapons. While planning a lunar gateway space station, the US has collaborated increasingly with private firms such as Space X, the first company into space and which was contracted to build a lunar landing module. In contrast to initiatives taking place in China and the US, Marshall suggests that Russia’s “best days in cosmology look to be behind it.” However, Putin has sought to reinvigorate Russia’s space programme as tensions have increased between Russia and the West in recent years. Its efforts depend heavily on its cooperation with China, with Russia regarded as the junior partner in the alliance to undermine US superiority.

Putin has sought to reinvigorate Russia’s space programme as tensions have increased between Russia and the West in recent years. Its efforts depend heavily on its cooperation with China.

The emphasis on the big three powers should not overlook the fact that an increasing number of states have invested to some extent in space activity. A brief survey of some of these takes place in chapter eight, which considers the move towards regional space blocs, such as the US allied European Space Agency, within which Italy, Germany and France have all been major players. While states as varied as Japan and India, Israel and the UAE are all referenced in this overview, Marshall notes that nobody comes close to challenging the big three.

In the book’s final part Marshall ponders some of the possibilities for the future of space exploration. The penultimate chapter sees him present some hypothetical scenarios, which illustrate some of the potential sources of future conflict. He highlights the danger of pre-emptive strikes in space and potential for escalation of conflict in such a scenario, while the biggest threat is considered most likely to arise from competition between the US and China. The book concludes by acknowledging the commercial opportunities which exist in space, while observing the various practical difficulties which may limit the extent to which they represent realistic propositions.

The Future of Geography makes an important contribution to understanding the political geography of space exploration and its impact on relationships between the world’s major powers.

The Future of Geography makes an important contribution to understanding the political geography of space exploration and its impact on relationships between the world’s major powers. It is not always easy to engage with some of the space jargon deployed, which presumes a certain amount of knowledge of space terminology and factual knowledge. There is also scope for the impact of space activity on international relations to be drawn out in more specific terms on occasion, to more effectively illustrate the possible real-world effects it may come to have. However, in a challenging and problematic arena of international political activity, the book offers insights which further the appreciation of the political geography of space exploration and provide illuminating food for thought as to what the future of space may hold.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Artsiom P on Shutterstock.

Abby Innes introduces Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail

In an excerpt from the introduction to her new book, Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail, Associate Professor of Political Economy at LSE’s European Institute Abby Innes considers how factors including the rise of neoliberalism have destabilised Britain’s governing institutions.

Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail. Abby Innes. Cambridge University Press. 2023.

Why has Great Britain, historically one of the strongest democracies in the world, become so unstable? What changed? This book demonstrates that a major part of the answer lies in the transformation of its state. It shows how Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions. This history has direct parallels not just in the United States but across all the advanced capitalist economies that adopted neoliberal reforms. The shattering of the British state over the last forty years was driven by the idea that markets are always more efficient than the state: the private sector morally and functionally superior to the public sector. But as this book shows, this claim was ill-founded, based as it was on the most abstract materialist utopia of the twentieth century. The neoliberal revolution in Great Britain and Northern Ireland – the United Kingdom – has failed accordingly, and we are living with the systemic consequences of that failure.

Why has Great Britain, historically one of the strongest democracies in the world, become so unstable? What changed? This book demonstrates that a major part of the answer lies in the transformation of its state. It shows how Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions. This history has direct parallels not just in the United States but across all the advanced capitalist economies that adopted neoliberal reforms. The shattering of the British state over the last forty years was driven by the idea that markets are always more efficient than the state: the private sector morally and functionally superior to the public sector. But as this book shows, this claim was ill-founded, based as it was on the most abstract materialist utopia of the twentieth century. The neoliberal revolution in Great Britain and Northern Ireland – the United Kingdom – has failed accordingly, and we are living with the systemic consequences of that failure.

Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions.

The rise of nationalist populism in some of the world’s richest countries has brought forward many urgent analyses of contemporary capitalism. What this book offers, by contrast, is the explanation of a dark historical joke. It explores for the first time how the Leninist and neoliberal revolutions fail for many of the same reasons. Leninism and neoliberalism may have been utterly opposed in their political values, but when we grasp the kinship between their forms of economic argument and their practical strategies for government, we may better understand the causes of state failure in both systems, as well as their calamitous results.

Comparing the neoclassical and Soviet economic utopias, [w]hat emerges are mirror images – two visions of a perfectly efficient economy and an essentially stateless future.

Britain’s neoliberal policies have their roots in neoclassical economics, and Part I begins by comparing the neoclassical and Soviet economic utopias. What emerges are mirror images – two visions of a perfectly efficient economy and an essentially stateless future. These affinities are rooted in their common dependence on a machine model of the political economy and hence, by necessity, the shared adoption of a hyper-rational conception of human motivation: a perfect utilitarian rationality versus a perfect social rationality. As the later policy chapters demonstrate, these theoretical similarities produce real institutional effects: a clear institutional isomorphism between neoliberal systems of government and Soviet central planning.

When it comes to the mechanics of government, both systems justify a near identical methodology of quantification, forecasting, target setting and output-planning, albeit administrative and service output-planning in the neoliberal case and economy-wide outputs in the Soviet. Since the world in practice is dynamic and synergistic, however, it follows that the state’s increasing reliance on methods that presume rational calculation within an unvarying underlying universal order can only lead to a continuous misfit between governmental theory and reality. These techniques will tend to fail around any task characterised by uncertainty, intricacy, interdependence and evolution, which are precisely the qualities of most of the tasks uploaded to the modern democratic state.

In neoliberalism, the state has been more gradually stripped of its capacity for economic government

The Soviet and neoliberal conceptions of the political economy as a mechanism ruled by predetermined laws of economic behaviour were used to promote pure systems of economic coordination, be that by the state or the market. Leninism, as it evolved into Stalinist command planning, dictated the near-complete subordination of markets to the central plan. In neoliberalism, the state has been more gradually stripped of its capacity for economic government and, over time, for prudential, strategic action, as its offices, authority and revenues are subordinated to market-like mechanisms. Both Soviet and neoliberal political elites proved wildly over-optimistic about the integrity of their doctrines, even as they demonised the alternatives.

For all their political antipathy, what binds Leninists and neoliberals together is their shared fantasy of an infallible ‘governing science’ – of scientific management writ large. The result is that Britain has reproduced Soviet governmental failures, only now in capitalist form. When we understand the isomorphism between Soviet and neoliberal statecraft, we can see more clearly why their states share pathologies that span from administrative rigidity to rising costs, from rent-seeking enterprises to corporate state capture, from their flawed analytical monocultures to the demoralisation of the state’s personnel and, ultimately, a crisis in the legitimacy of the governing system itself. This time around, however, the crisis is of liberal democracy.

The book’s policy chapters in Part II explore how the neoliberal revolution has transformed the British state’s core functions in the political economy: in administration, welfare, tax and regulation and the management of future public risk.

After setting out the philosophical foundations of these ideologies, the book’s policy chapters in Part II explore how the neoliberal revolution has transformed the British state’s core functions in the political economy: in administration, welfare, tax and regulation and the management of future public risk. In Part III I examine the political consequences of these changes, and demonstrate how Britain’s exit from the European Union has played out as an institutionally fatal confrontation between economic libertarianism and reality. The final chapter considers how the neoliberal revolution, like its Leninist counterpart, has failed within the terms by which it was justified and instead induced a profound crisis not only of political and economic development but also of political culture.

Under ‘late’ neoliberalism we can see a similar moment of political hiatus, as neoliberal governments likewise resort to nationalism and the politics of cultural reaction to forestall public disillusionment and a shift in paradigm.

I use different periods of Soviet history as an analytical benchmark throughout the book, but the Brezhnev years (1964–1982) were those of the fullest systemic entropy: the period of ossification, self-dealing and directionless political churn. Under ‘late’ neoliberalism we can see a similar moment of political hiatus, as neoliberal governments likewise resort to nationalism and the politics of cultural reaction to forestall public disillusionment and a shift in paradigm. I use the United Kingdom as the case study because it was both a pioneer of these reforms and, in many respects, has gone furthest with them. If neoliberalism as a doctrine had been analytically well-founded, it was in the United Kingdom, with its comparatively long and strong liberal traditions, that we should have seen its most positive outcomes.

By the early 2020s the Conservative government of Boris Johnson had sought to criminalise peaceful protest, to constrain media independence and to insulate the political executive from parliamentary and public scrutiny.

To be clear, Britain’s neoliberals were never totalitarians of the Soviet variety. They never used revolutionary violence to create a one-party state, deployed ubiquitous intelligence agencies to enforce repression or used systems of mass incarceration and murder for political ends. Britain’s neoliberal consensus has nevertheless favoured a one-doctrine state, and the violent suppression of specific, typically economy-related, protests has been a periodic feature of its politics since 1979. Britain’s neoliberal governments have also developed an increasingly callous attitude to social hardship and suffering. Most troubling of all is that the more neoliberalism has been implemented, the more the country has been driven to the end of its democratic road. By the early 2020s the Conservative government of Boris Johnson had sought to criminalise peaceful protest, to constrain media independence and to insulate the political executive from parliamentary and public scrutiny. In short, it had abused its authority to disable legitimate political opposition. What I hope to explain is why any regime that commits itself to neoliberal economics must travel in this direction or abandon this ideology.

What follows is an argument about the collapse of the empiricist political centre and its replacement by utopian radicalism. Specifically, this is a story of how the pioneering and socially progressive philosophy of liberalism is being discredited by utopian economics and the practically clientelist methods of government that follow from it, just as the politics of social solidarity essential to a civilised world was undermined by the violence and corruption of the Soviet experiment. As the old Soviet joke had it, ‘Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. Communism is its exact opposite.’ There are, of course, many challenges distinct to neoliberalism and I pay attention to them, but my purpose here is to see what we can learn about the political economy of the neoliberal state when we look at it through the lens of comparative materialist utopias.

Note: This excerpt from the introduction to Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail by Abby Innes is copyrighted to Cambridge University Press and the author, and is reproduced here with their permission.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: globetrotters on Shutterstock.

Team B and the Jerusalem Conference: How Israel Helped Craft Modern-Day “Terrorism”

Since Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza began, Zionist officials, pundits, journalists, and their Western opposite numbers have endlessly invoked the sinister specter of “terrorism” to justify the industrial-scale slaughter of Palestinians. It is because of “terrorism,” twice-failed U.S. Presidential candidate and unconvicted war criminal Hillary Clinton representatively wrote for The Atlantic on November 14 that “Hamas must be permanently erased.” Destroyed hospitals and schools and civilians killed en masse are reasonable “collateral damage.” Such is the unparalleled evil of “terrorists.”

Yet, the relentless stream of heart-rending clips documenting the Israeli Occupation Force (IOF) Holocaust deluging social media feeds the world over, and the ever-ratcheting child death toll has compelled countless citizens to ask, “If Hamas are terrorists, then what are Zionists?” It is surely no coincidence YouTube recently yanked the official video of a groundbreaking track by renowned rapper and MintPress News contributor Lowkey, “Terrorist?” posing this precise question.

“Terrorist?” was released in 2011, at the height of the U.S. Empire’s “War on Terror.” Then, the purported global threat of “terrorism” was exploited throughout the West to savage civil liberties at home and wage relentless illegal military “interventions” abroad. Mainstream usage of the term precipitously plummeted thereafter. It is only now regaining popular currency due to the Gaza genocide.

This is no accident. As we shall see, Israel – and specifically its veteran leader, Benjamin Netanyahu – was fundamental to concocting the mainstream conception of “terrorism,” explicitly to delegitimize anti-imperial struggles while validating Western state violence directed at oppressed peoples across the Global South. The impact of this informational assault can be felt in every corner of the world today – not least Gaza.

In fact, one might reasonably conclude the specific foundations of Nakba 2.0, which is unfolding in grisly real-time right now, were laid decades ago as a result of the connivances of Netanyahu, the international Zionist lobby, and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. What follows is the little-known history of how “terrorism” came to be. A majority of the world’s population – the Palestinian people in particular – live with the mephitic consequences every day.

It Begins…

Our story starts in 1976, at the peak of détente between the U.S. and Soviet Union. After two-and-a-half decades of bitter enmity, the two superpowers resolved to peaceful coexistence at the start of the decade. They collaborated to systematically dismantle the structures and doctrines that defined the immediate post-World War II era, such as Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.).

In May of that year, the CIA produced its annual National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), a comprehensive report combining data from various intelligence agencies intended to be a basis for crafting foreign policy. In keeping with the past five years, it concluded the Soviets were in severe economic decline, favored diplomacy over conflict, and desperately sought an end to the Cold War. Such findings lay behind Washington’s push for détente and Moscow’s eager acceptance of major disarmament and arms control treaties.

However, newly-appointed CIA director George H. W. Bush categorically rejected these conclusions. He sought a second opinion and constructed an independent intelligence cell to review the NIE. Known as Team B, it was composed of hardcore Cold Warriors, defense-industry-funded hawks, and rabid anti-Communists. Among them were several individuals who would become leading figures in the neoconservative movement, such as Paul Wolfowitz. Also present were the infamous CIA and Pentagon dark arts specialists who had been professionally ostracized due to détente.

Team B duly reviewed the NIE and rubbished each and every one of the Agency’s findings. Rather than dilapidated, impoverished and teetering on total collapse, the Soviet Union was, in fact, more deadly and dangerous than ever, having constructed a vast array of “first strike” capabilities right under the CIA’s collective nose. To reach these bombshell conclusions, Team B relied on a confounding hodgepodge of peculiar logical fallacy, paranoid theorizing, crazed conspiratorial conjecture, unsupported value judgments, and amateurish circular reasoning.

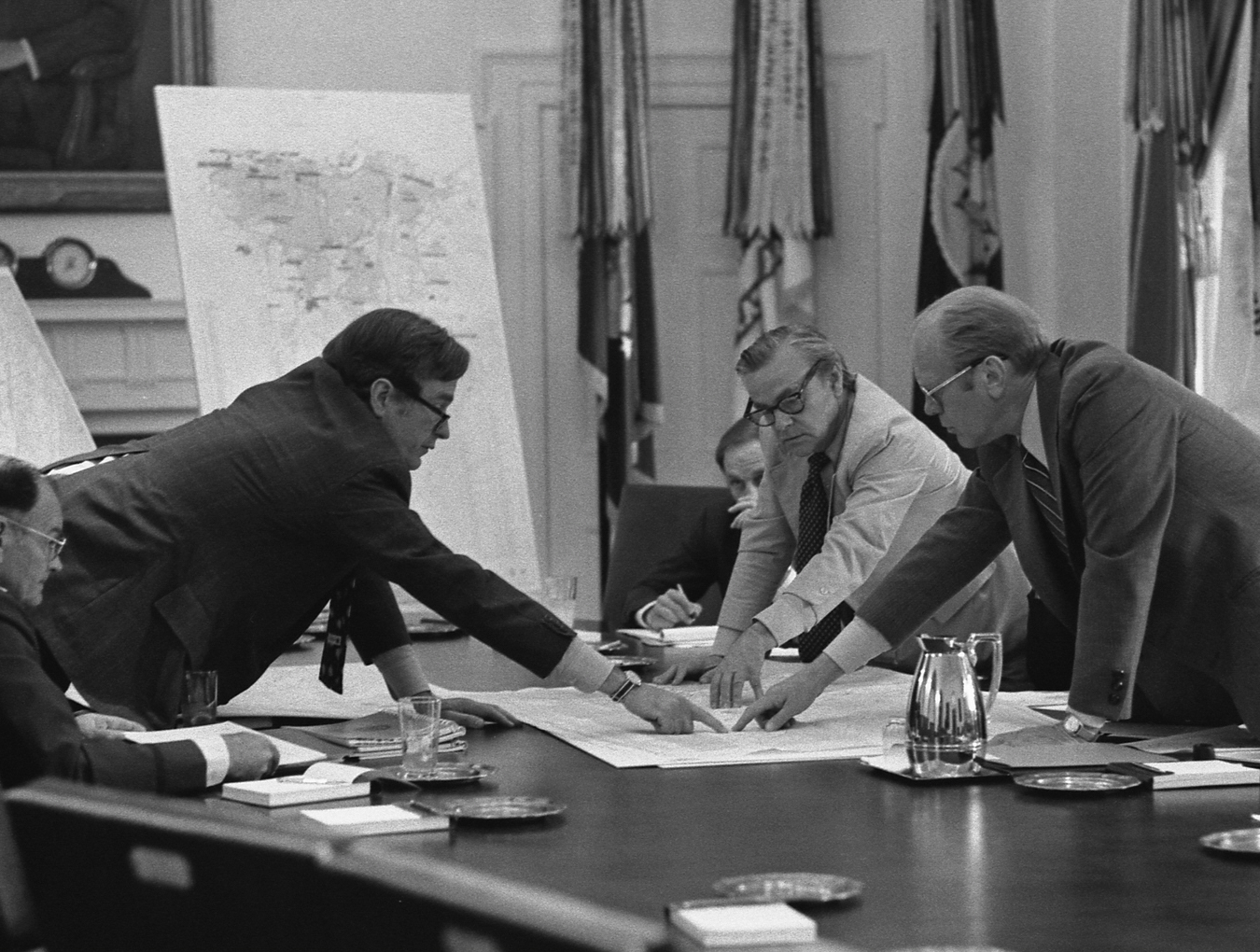

Then-CIA director George H.W. Bush looks over a map of Beirut, Lebanon, with President Gerald Ford. Photo | CIA Archives

Then-CIA director George H.W. Bush looks over a map of Beirut, Lebanon, with President Gerald Ford. Photo | CIA Archives

For example, Team B repeatedly assessed that a lack of evidence Moscow possessed weapons systems, military technology, or surveillance capabilities comparable or superior to Washington’s own was inverse proof the Soviets, in fact, did. They were so sophisticated and innovative, Team B concluded, that they couldn’t be detected or even comprehended by the West. Team B’s analysis was confirmed to be a total fantasy when the USSR collapsed. Yet, its methods informed all subsequent NIEs throughout the Cold War and likely endure today.

On June 27 of that year, mere weeks after Team B was set to work on reigniting the Cold War, Air France Flight 139, en route to Paris from Tel Aviv, was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Redirected to a Ugandan airport, the plane was greeted on the runway by Idi Amin’s military, who ushered the passengers – the majority of whom were Jewish or Israeli – into the terminal, watched over by scores of soldiers, intended to prevent their escape or rescue.

The hijackers relayed a demand to the government of Israel. Unless a ransom of $5 million was paid to them and 53 Palestinian prisoners were released from jail, the hostages would be executed. In response, 100 elite IOF commandos launched an audacious action to free the hostages. Their mission – known as the Entebbe Raid – was a stunning success. All but four hostages were rescued alive, and the IOF lost just one commander – Yonatan (Jonathan) Netanyahu, the older brother of Israel’s sitting Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

‘Propaganda to Dehumanize’

For years, by that point, Israeli officials had been attempting to popularize the term “terrorism” to explain the motivations and actions of Palestinian freedom fighters. That way, their righteous fury at repression could be reframed as a destructive ideology of violence for violence’s sake without rationale and Zionist colonial tyranny as warranted self-defense. This effort became turbocharged in September 1972, when the kidnapping of 11 Israeli athletes at that year’s Olympics in Munich by Palestinian militants ended with all hostages murdered.

This particularly public bloodshed centered world attention on Israel and left Western citizens wondering what could’ve possibly inspired such actions. Zionists had hitherto managed to largely conceal their systematic, state-enforced repression and displacement of Palestinians from the outside world. Journalists were kept well away from the scenes of major crimes. At the same time, Amnesty International’s Israeli branch was secretly financed and directed by Tel Aviv’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to whitewash facts on the ground.

For the Netanyahu family, the Entebbe raid was a tragedy – but also an ideal opportunity to validate and internationalize the concept of “terrorism,” as espoused by Zionists. In 1979, Benjamin Netanyahu founded the Jonathan Institute in honor of his slain brother. Its purpose, he said, was:

To focus public attention on the grave threat that international terrorism poses to all democratic societies, to study the real nature of today’s terrorism, and to propose measures for combating and defeating the international terror movements.”

In 1983 Netanyahu explained what terrorism is not

If you miss a target and a bomb accidentally falls on a Children’s hospital it’s not terrorism

Does it hold true in 2023!!! pic.twitter.com/6DiHRv0IKk— Dr Nilima Srivastava (@gypsy_nilima) October 21, 2023

In July that year, the Institute convened the Jerusalem Conference on International Terrorism (JCIT) in Jerusalem’s Hilton Hotel. It gathered together a 700-strong mob of Israeli government officials, U.S. lawmakers, intelligence operatives from across the ‘Five Eyes’ global spying network, and Western foreign policy apparatchiks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many representatives of Team B were in attendance. For four days and seven separate sessions, speaker after speaker painted a disturbing picture of the worldwide phenomenon of “terrorism.”

They unanimously declared that all “terrorists” constituted a single, organized political movement that was being secretly financed, armed, trained, and directed by the Soviet Union. This devilish nexus, it was claimed, posed a mortal threat to Western democracy, freedom, and security, requiring a coordinated response. Eerily, as academic Diana Ralph later observed, the JCIT’s collective prescription for tackling this purported menace was precisely what transpired just over two decades later during the “War on Terror”:

[This included] pre-emptive attacks on states that are alleged to support ‘terrorists’; an elaborate intelligence system apparatus; slashed civil liberties, particularly for Palestinians targeted as potential terrorists, including detention without charge, and torture; and propaganda to dehumanize ‘terrorists’ in the eyes of the public.”

Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin addressed the JCIT’s opening session. He set the tone by claiming Western state violence was ultimately “a fight for freedom or liberation” and, therefore, fundamentally opposed to “terrorism.” He concluded his remarks by imploring the assembled throng to go forth and promote the conference’s message once it was over. And they did.

‘The Terror Network’

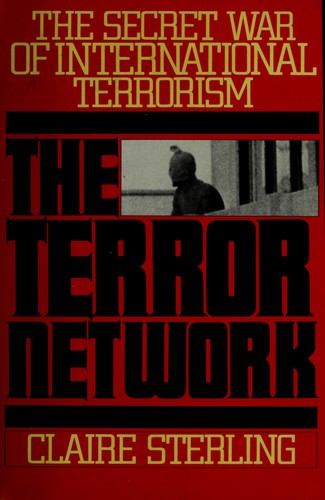

Among the JCIT attendees was American author and journalist Claire Sterling, who cut her teeth as a reporter decades earlier at the Overseas News Agency, an MI6 propaganda operation seeking to boost U.S. public support for entering World War II. Following the conference, she frequently amplified the claims of JCIT speakers in articles for prominent newspapers, leading to an epic March 1981 front-page exposé in The New York Times, “Terrorism: Tracing The International Network.”

A book published later that year, “The Terror Network,” expanded significantly on Sterling’s oeuvre and firmly cemented the notion of Moscow as a grand spider sat in the middle of a vast, globe-spanning web of deadly political violence in the Western public mind. It caused a sensation upon release, receiving rave reviews from major news outlets, being translated into 22 languages, and becoming a bestseller in several countries.

Most significantly of all, “The Terror Network” had a particularly potent impact on newly-inaugurated President Ronald Reagan and his CIA chief William Casey. Committed anti-Communists, they entered office desperately seeking a pretext for brutally crushing left-wing, nationalist opposition to U.S. imperialism in Latin America. Sterling’s work provided ample ammunition for achieving that bloodsoaked objective and was key to the White House decisively shattering détente, a process begun by Team B five years earlier.

Most significantly of all, “The Terror Network” had a particularly potent impact on newly-inaugurated President Ronald Reagan and his CIA chief William Casey. Committed anti-Communists, they entered office desperately seeking a pretext for brutally crushing left-wing, nationalist opposition to U.S. imperialism in Latin America. Sterling’s work provided ample ammunition for achieving that bloodsoaked objective and was key to the White House decisively shattering détente, a process begun by Team B five years earlier.

Consequently, “The Terror Network” was circulated among U.S. lawmakers and heavily promoted overseas on the Reagan administration’s dime. Casey furthermore tasked his Agency with verifying its thesis. They quickly assessed Sterling’s work to be irredeemable garbage, ironically enough, as it was heavily influenced by CIA black propaganda. Enraged, Casey demanded the evaluation be revised. An updated appraisal was less scathing but nonetheless stressed the book was “uneven and the reliability of its sources varies widely,” while “significant portions” were “incorrect.”

Still dissatisfied, Casey asked a CIA “senior review panel” charged with scrutinizing Langley’s formal estimates to write their own report on the subject. They concluded the Soviets did offer limited financial, material and practical assistance to a handful of anti-imperial Global South liberation movements, some of which were labeled “terrorists” by Western powers. But there was “insufficient evidence” of Muscovite culpability for the entire global phenomenon of “terrorism,” let alone funding and directing such entities as dedicated policy.

Undeterred, when Casey personally delivered the report to Reagan, he allegedly said of its findings, “Of course, Mr. President, you and I know better.” So it was CIA-backed death squads that ran roughshod across Washington’s “backyard” throughout the 1980s in the name of neutralizing Soviet influence in the region. Their actions were heavily informed by the Agency’s guerrilla warfare manual, which encouraged assassinations of government officials and civilian leaders and deadly attacks on “soft targets” such as schools and hospitals. “Terrorism,” in other words.

‘We Are All Palestinians’

Another example of Reagan’s “terrorism” was sponsoring Afghanistan’s Mujahideen resistance fighters in their battle with – ironically enough – the Soviet Red Army. This policy endured after the “Evil Empire” was vanquished. The same militants were transported to Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s to aid and abet the painful, forced death of Yugoslavia.

When these covert actions produced “blowback” in the form of the 9/11 attacks, several individuals who attended the JCIT, and their acolytes, were elevated to the Bush administration due to their supposed “terrorism” expertise. Meanwhile, with public and state-level fears of “terrorism” ramping up significantly the world over, many Western countries turned to Israel for advice and guidance on how to tackle the issue. As Nentyahu commented in 2008:

We are benefiting from one thing, and that is the attack on the Twin Towers and Pentagon and the American struggle in Iraq.”

This was not only because 9/11 “swung American public opinion in [Israel’s] favor.” In a blink, Zionist repression and slaughter were transformed from a source of international embarrassment and obloquy into a compelling sales pitch and unique selling point for Tel Aviv’s welter of “defense” and “security” firms. The Occupied Territories became laboratories, their inhabitants test subjects, upon whom new weaponry, surveillance methods, and pacification techniques could be trialed by the IOF, then marketed and sold overseas.

Netanyahu shows reporters a copy of a Syrian passport allegedly found on a Palestinian fighter that washed ashore in Gaza, 1991. Jerome Delay | AP

Netanyahu shows reporters a copy of a Syrian passport allegedly found on a Palestinian fighter that washed ashore in Gaza, 1991. Jerome Delay | AP

It is not for nothing that graphic videos showcasing IOF “surgical strikes” on Palestinians, their homes, schools, and hospitals are proudly displayed at international arms fairs, and private demonstrations of invasive surveillance tools such as Pegasus routinely wow repressive foreign security and intelligence agencies behind-closed-doors.

On top of a significant financial benefit, there is a diplomatic dividend, too. Israel secures an invaluable censure-stifling goodwill from customers, therefore permitting the Zionist project of permanently purging Palestine of its indigenous inhabitants to persist untrammeled. We see a palpable demonstration of this currently. While the streets of almost every major Western city have regularly teemed with pro-Palestine fervor ever since the latest attack on Gaza began, the protesters’ elected representatives are at best silent, at worst, actively complicit.

Impassioned chants of “We are all Palestinians!” have been a frequent fixture at these events. This rallying call is highly apposite, for in addition to expressing sympathy and solidarity with the Palestinian people, it is urgently incumbent upon us all to reflect that the very same techniques and technologies of control and oppression to which they have been so cruelly subjected daily for decades are now firmly trained on us as well, as a result of Israel’s invention of “terrorism.” As such, it is no exaggeration to say Palestinians are canaries in the coalmine of humanity.

Feature photo | Illustration by MintPress News

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist and MintPress News contributor exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions. His work has previously appeared in The Cradle, Declassified UK, and Grayzone. Follow him on Twitter @KitKlarenberg.

The post Team B and the Jerusalem Conference: How Israel Helped Craft Modern-Day “Terrorism” appeared first on MintPress News.