Housing

How Albanese could tweak negative gearing to save money and build more new homes

There are two things the prime minister needs to get into his head about tax. One is that saying he won’t make any further changes no longer works. The other is that negative gearing doesn’t do much to get people into homes. Anthony Albanese seemed to have taken the first point on board when he Continue reading »

We can’t rely on developers to fix the housing crisis

If you were running the state suffering the very worst of Australia’s housing disaster, a state where the number of public and community housing dwellings actually went backwards last financial year, you might want to grab any and every opportunity to ease the crisis – but you’re not running New South Wales. Since defeating the Continue reading »

‘The Feudal Leasehold System That Threatens a Repeat of the Grenfell Disaster’

Last week a block of flats on Elm Road in my Brent North constituency caught fire. It took five hours, 125 firefighters and 20 fire engines to bring the fire under control. Thankfully, it was not another Grenfell – all residents were evacuated to safety – but the reason the fire spread so quickly was because, six years on from that tragedy, this building still had Grenfell-style combustible cladding on the outside.

Octavia Housing, who own the block of flats, attended a residents meeting which we held three days later. The acting Chief Executive was keen to assure everyone that Octavia’s “top concern, was residents’ safety". However, the truth is that for the past three years Octavia have known about the combustible cladding but have instead engaged in a protracted dispute with the original developers, Vistry, rather than get on and remove the cladding themselves and argue about who ought to pay for it, later.

This is the very sort of legal wrangling that Michael Gove’s Building Safety Act was supposed to stop. It hasn’t. In reality, the Act has trapped thousands of residents living in Leasehold apartments with multiple fire safety defects. They are prisoners in their own homes.

The stipulation that all residential buildings over 18 meters (or six storeys) should have an EWS1 form, to show that an appraisal of the External Wall System has been carried out by a qualified professional was supposed to reassure lenders, and enable mortgages to be offered on buildings with cladding in place. In fact the market has acted in precisely the opposite way.

Problems include the difficulty of finding a qualified professional to carry out the assessment, the reluctance of banks to provide mortgages on buildings where the remediation work has not yet been carried out, and sometimes the inability of leaseholders to force their landlord to carry out the Fire Risk Assessment at all, even though the law stipulates only the freeholder of the building can do so. All these – combined with the complexity of the five different EWS1 ratings – have ensured that those who are keen to sell up and get out of unsafe buildings are unable to do so.

A Feudal Hangover

The wider problem is that when people buy an apartment, they often assume that they are becoming a home owner. In fact they are not. They simply possess a piece of paper that gives them the right to live there for a long period of time – typically 99 or 125 years. It is the freeholder who has all the rights: the right to paint the doors and windows, the right to put on a new roof, the right to repair the lift. So if you live on the 10th floor and you want the lift repaired, you have to wait until your landlord decides to do it. They decide who does the work, how much it will cost, and when it will be done; but it is you that pays the bill.

If that strikes you as an intolerable system where the imbalance of power between freeholder and leaseholder, could lead to corruption and exploitation, that is because it is. Take the topical example of buildings insurance: in the recent Canary Riverside case, a first tier tribunal found that £1.6million of insurance commission had been unreasonably paid to a landlord owned company by an FCA-regulated broker. And neither party could support the payment with any evidence of a written contract.

The residential leasehold system exists nowhere else in the world. It is a hangover from the feudal system, an era where you lived at your lordship’s pleasure and owed your fealty to him. It has no place in a modern property-owning democracy. Successive governments have promised to replace it with Commonhold, where flat owners own their property along with a share in the common parts of the building.

There would be no separate landlord managing the building without residents’ consent. The residents would take on the responsibility of managing it themselves or appointing a managing agent to do so on their behalf – a managing agent they could get rid of if they were not satisfied. No more inflated service charges, no more failure to do repairs.

https://vimeo.com/909871478

The 'Leasehold' Documentary produced by Labour MP Barry Gardiner

For the past three weeks I have been sitting in the Bill Committee of the Leasehold and Freehold Reform Bill. It is 133 pages of tinkering with a fundamentally flawed and unjust system. Even the Minister was prepared to acknowledge that it will not solve the essential problems leaseholders face. But such bills come round rarely – the last attempt at reform was 22 years ago. This week rumour has it, the Labour Manifesto will be finalised. If it fails to contain a bill abolishing residential leasehold and bring in commonhold, there will be 5 million angry leaseholders who want to know why.

But commonhold is for the future. What of the residents who live in buildings blighted by cladding and other fire safety defects now? The government has rightly said the residents should not have to pay to have these buildings remediated. They say that it is the developers and owners of the building who should bear the cost. But many developers have gone out of business.

Others have sold the building on multiple times – often to a company now located in the Cayman Islands or some other tax haven beyond the jurisdiction of English law. Sometimes, like my constituents in Elm Road the owners and developers are locked in protracted legal dispute arguing about costs as their property burns. In the meantime, residents continue to be at risk.

Of course, the Government could introduce a windfall levy on the construction industry and fund the work up front, recovering it thereafter from those developers who caused the problem. But the idea of an interventionist government that enters into the market to solve people’s problems is perhaps a thing of the past. Such an idea might harken back to the days when governments created things like the National Health Service or decided that there should be free education to the age of sixteen. Worst of all, politicians might find it was actually popular.

Barry Gardiner MP has been campaigning against residential leasehold for 25 years. On Monday February 5 he launched his documentary 'Leasehold'

Common sense is nowadays award winning…

Well I never thought I would have to be linking to ‘Conservative home’ where my local Police and Crime Commissioner has discovered that giving ex prisoners jobs is beneficial… Who knew?? How clever is that? I despair – the scheme has apparently won awards – for what is, I suggest, the blindingly obvious fact that... Read more

Grenfell: Michael Gove Deflecting the Blame Away from Conservative Politicians

Michael Gove is on the warpath. In the Housing Secretary’s crosshairs are the private contractors and suppliers to the Grenfell Tower.

In Gove’s view, they were to blame for the rapid spread of the fire which killed 72 people in West London in 2017.

According to Gove, they now have a duty to put right other high-rise towers and apartment blocks that carry the same insulation and cladding materials as Grenfell. In typical Gove fashion, he has not held back in his criticism, accusing cladding company Arconic, of engaging in “shameful practices” and displaying “an abhorrent culture of disregard for the safety of residents in their homes.”

He claimed that Kingspan, the Irish insulation maker, “is a company that gives capitalism a bad name”.

Again, his characteristic, guns-blazing tactic includes using all fronts, including social media, to put his message across.

Anyone reading his department’s postings, and there is much more, could be forgiven for supposing Arconic, Kingspan and the other firms involved in the 2016 installation of cladding and insulation at Grenfell were entirely responsible for the terrible inferno and loss of life.

You see, it’s all the fault of the greedy, grasping commercial sector, putting profits before people’s lives. The Secretary of State ends one diatribe with: “My Government Department will continue to be driven by its commitment to protect people in their homes. People who bought their rented homes in good faith and whose safety continues to be threatened by your products deserve better from the companies who have exploited their basic need for a home. Those companies who do not share our commitment to righting the wrongs of the past must expect to face commercial consequences.”

It’s an election year, and for Gove, putting himself in the shoes of the little man is a key part of the Tory strategy. By targeting private business he is exploding the age-old myth that the Tories are on the side of big business.

Again, though, anyone would think that the public sector had no role to play, that the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where Grenfell stands, central government and London Fire Brigade bore no responsibility - that the tragedy was all down to the commercially rapacious profit chasers.

Which is why it comes as a surprise, then, to read that Arconic and Kingspan are not the worst offenders - that the worst is the local royal borough council, and that Gove’s own government and the fire service shoulder more of the burden than Kingspan ‘that gives capitalism a bad name.’

The Bindman Settlement

While the Grenfell Tower inquiry continues on its pain-staking journey, nine of those organisations, commercial and public, involved in the disaster undertook an ADR, an alternative dispute resolution, as a way of ensuring compensation reached the victims’ families and those forced from their homes in shorter order than if they’d waited for any potential litigation to conclude.

Represented by teams of lawyers, they agreed to meet before a senior judge who would determine the sum to be awarded and apportion their contributions.

In May last year, it was announced that the ADR was to pay £150m to those affected. But how that figure was broken down was not revealed, apparently for reasons of commercial confidentiality.

I’ve seen the percentage breakdown and it shows, top on 35.84 per cent is the borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Next is Arconic on 22.84 per cent. Then, Rydon (builders), 10.84 per cent, Celetex (manufacturer of most of the insulation) at 9.84 per cent. The fire service’s share is 5.84 per cent, the same as the Government’s, Exova (fire testing) is 3.24 per cent while Whirlpool, which made the fridge where the fire originated and Gove’s target Kingspan are in for the smallest portions, 2.84 per cent each. The accuracy of the figures has been confirmed.

The ‘Bindman Settlement’ - so-called after the leading London law firm where the nearly two years worth of detailed, behind-closed-doors discussions were held - was mediated by Lord Neuberger, the former president of the Supreme Court. In all, 900 people, including those who lost their relatives and those required to relocate, agreed to the out-of-court settlement. The ADR route was chosen after a claim was lodged at the High Court in 2021.

Five of those involved in the Grenfell refurbishment, which is when the cladding was added, chose not to participate in the Bindman process: CEP architects, Studio E architects, CS Stokes fire safety assessor, Harley Facades and Artelia project consultants.

“Some firms stepped up and others didn’t,” said one of the Bindman signatories. “We took the view that you can’t be a proxy where responsibility is concerned.”

The settlement does not have any bearing on the Grenfell Tower inquiry. Nor does it impact any potential criminal action. “Who paid what doesn’t necessarily reflect blame,” said the signatory.

Nevertheless, in the absence of the official inquiry’s findings, it is the nearest we have to apportioning fault.

Possibly, because the percentages are supposed to remain secret, Gove is confident he can lambast the companies, confident of not being challenged - and he can choose to ignore the larger role played by the public sector.

That the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the Government also happened to be led by Tories at the time of the tower’s refurbishment in 2016, is something else Gove may be keen not to dwell upon.

For all the talk, public and social housing just got worse

The Productivity Commission has released a damning report on Australia’s worsening public and community housing disaster. Needs have increased, supply has not and the various announced policies stretching out in the distance aren’t enough to make a significant difference. However bad you think the Australian public and community housing crisis is, it worsened over the Continue reading »

Growth Battles in Chittenden County

by Dave Rollo

The Green Mountains of Vermont. (JJ Sky’s the Limit)

Vermont takes its name from the French Monts Verts, or Green Mountains, the state’s rolling hills that host maple, birch, and beech forests in the south and spruce and fir in the north. Quaint towns and farms, many retaining their historic structures, are nestled in the mountain valleys. Lakes, streams, and wetlands are plentiful. And farms are everywhere: Vermont consistently ranks as one of the top states in the nation for local food production.

The verdant beauty of the Green Mountain State is striking, but preserving its beauty is a struggle as the state’s fields and forests attract green of a different kind. The state’s revered rural landscapes represent potentially lucrative investments for developers.

Developers have sought to expand urban development into surrounding green areas since the end of World War II. This is particularly evident in Chittenden County, the home of Burlington, Vermont’s largest city. More than a quarter of Vermonters live there, and it remains on the front line of the struggle against sprawl. Recent battles there highlight the tensions between providing housing and protecting the environment. They also demonstrate that well-organized groups of citizens can make inroads against powerful pro-growth interests.

Burlington’s Growing Pains

In the latter half of the 20th century, Chittenden County lost farmland at an alarming rate; farmland’s share of total area fell from 73 percent to just 24 percent between 1950 and 1992. Commensurate with this loss was a doubling of population. And since 1945, the number of residents has more than tripled.

In the late 1960s, politicians and the public began to clamor for action to prevent further loss of land to sprawl. The legislature responded in 1970 with Act 250, a landmark land-use statute. Years later, the Republican governor who signed the legislation recognized the Act as the most significant of his administration.

Act 250 marked a sea change in land use. It required that a project, after passing review at the local level, meet ten criteria to earn further review by the state’s Natural Resources Board. Then it is reviewed by one of nine regional Environmental Commissions. Environmental Commission review has been particularly successful in regulating developments of ten or more housing units or building lots.

Analysts credit Act 250 with protecting Vermont’s agrarian spaces, wetlands, and forests. The development process mandated by the Act encourages the participation of neighbors in targeted areas, bringing the perspectives of various stakeholders before the commissions. Although developers find the requirements onerous and time consuming, most permits are granted—none were rejected in 2022, and only one was rejected in 2021.

Will the scarlet tanager continue to have a home in Vermont? (Jen Goellnitz)

Still, developers complain of a chilling effect of the Act, as the review can be lengthy and costly. And housing advocates, concerned about housing scarcity and rising home prices, have joined developers in critiquing the Act.

Legislators are now debating reform of Act 250, which the current Governor favors. Changes are likely soon. Some proposed changes are quite benign, such as exempting farm restaurants or farm stands from the density provisions of the law. But loosening standards and lowering barriers threatens to generate the very sprawl that the law was enacted to prevent. Resident groups such as Better (Not Bigger) Vermont eye the growing coalition of developers and housing advocates with concern.

Meanwhile, the legislature adopted the Home Act in June 2023, which critics fear could encourage sprawl. The intent of the Home Act is purportedly to elevate density in village centers of rural communities to increase housing stock. To this end, the Act permits “plexing,” the subdividing of existing single-family homes, usually to create rental units.

While creating density through plexing could be beneficial in town cores, the Act’s simultaneous elimination of single-family zoning statewide reduces opportunities for home ownership, a key strategy for building wealth. In contrast, duplexes convert housing stock to rentals where equity building isn’t possible.

Many advocates of a supply-side approach to the housing crunch fail to consider that the problem is not just a shortage of structures, but how they are used. Short-term rentals (Airbnb) and the purchase of second homes effectively take homes off the sale and rental markets. The effect is to reduce housing availability in Vermont, just as it does elsewhere in the country.

Infrastructure and Growth Pressures

As the state legislature begins to ease development review and encourage greater density through upzoning (allowing greater height, density, or both), local governments are responding by relaxing local land-use codes. Planning commissions typically develop eight-year plans and create zoning regulations that are forwarded to selectboards, the legislative bodies that govern towns in Vermont. The revision of zoning plans provides an opening for growth advocates to expand development in rural towns—especially the bedroom communities of large cities such as Burlington.

Summer 2023 algal bloom in Lake Champlain. (southherovoters.org)

Growth in these communities takes infrastructure, such as roads and waterworks, which benefits developers. Expanding sewer treatment, for example, is a prerequisite of housing and commercial development. At least, it should be a prerequisite. Unfortunately, a common practice of growth advocates is to pressure communities to develop more housing even though existing infrastructure is inadequate to accommodate it.

Many communities impacted by growth and sprawl commonly complain about a lack of concurrency of infrastructure and services—ensuring that infrastructure is possible and affordable before a new area is developed. But concurrency is rarely prioritized, leading to stress on existing infrastructure that is costly in both environmental and economic terms.

In Vermont, the case of combined sewer systems, in which sewage and stormwater flow through the same pipes, demonstrates the lack of infrastructure capacity. Combined sewer-stormwater infrastructure renders water treatment vulnerable to flooding during heavy rains. This can bring about sewage overflows into waterways, such as the White River, a tributary of the Connecticut River, the largest river in New England. Sewage overflows also contaminate Lake Champlain.

Heavy summer rains in July 2023 caused an antiquated sewer pipe to rupture, spilling 10 percent of Burlington’s wastewater into the Winooski River, which feeds into Lake Champlain, causing extensive contamination of the lake. Combined sewer-stormwater overflow also contributes to poisonous bacterial blooms, which diminish fishing and swimming opportunities and threaten the health of pets and wildlife.

During the COVID pandemic, federal funding from the American Rescue Plan (ARPA) was ostensibly made available for upgrading antiquated sewage systems such as combined sewage-stormwater systems and septic fields. However, in Vermont this funding was often used to expand sewage treatment plants in rural areas, stimulating growth there. As a result, combined sewage-stormwater systems still plague the state.

Westford Pushes Back Against Growth

Westford, Vermont, a town less than 10 miles from greater Burlington, illustrates how citizens can stand against development interests to protect small-town rural character. In 2023, the state proposed use of ARPA funds for construction of a wastewater treatment plant that would permit a 60 percent increase in Westford residences. Ninety percent of the construction cost of the $4-million plant was to be financed by the state, but Westford residents needed to approve a bond to cover $400,000 of the cost.

Westford, Vermont town center. (Bernhard Wunder)

Knowing that the plant’s extra capacity would be utilized by development interests, residents joined forces to educate the town and vote down the referendum that was required for the bond passage.

Residents found themselves pitted against the town planning commission, and the local media was unsympathetic to their objections. They were even removed from a statewide listserv used to provide information on the project, according to Bob Fireovid, a farmer and activist in the greater Burlington area.

Despite these obstacles, the group created a political action committee and a website with information including videos describing the proposal. They also peppered the community with signs urging a “No” vote on the referendum. To the surprise of the growth boosters, the referendum was defeated in November, 2023 in a 532-to-488 vote. Furthermore, the Westford Selectboard went further, declaring that the vote represented not just a rejection of the bond, but a referendum on the wastewater project. The project is now suspended

Tale of Two Heroes

Other rural communities threatened by Burlington sprawl are the towns of North and South Hero, located on Grand Isle in Lake Champlain. South Hero is just 12 miles from Burlington, while North Hero, on the northern end of the island, is more distant. Towns in Vermont make changes to their town plans every eight years, and both Hero draft plans were opened to public review in 2022. A referendum in South Hero and a vote by North Hero’s Selectboard were then to follow. That’s when residents got busy.

Many residents of both towns were alarmed at the extent of the proposals, which increased density and altered zoning over large areas extending from their town centers. The plans, they argued, weren’t created in the interests of residents at large, but to serve commuters to Burlington, South Burlington, and Essex Junction.

Residents of South Hero developed a website to post planning documents, alert neighbors to upcoming meetings, and describe the hazards of a plan that would have expanded development into their rural community.

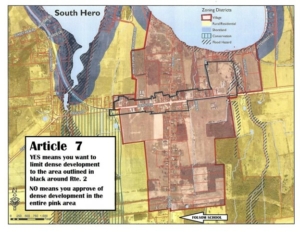

On the South Hero ballot were two alternative proposals: one to limit the extent of growth and the other to expand the dense development many-fold. The proposal to limit sprawl failed by about 50 votes of the 650 cast.

The referendum question for South Hero. (southherovoters.org)

In contrast, residents of North Hero opposed to comprehensive density increases were able to restrict multi-family housing primarily to a limited zone near the town center. The North Hero Selectboard will permit denser housing in rural neighborhoods only by conditional use, which requires a board hearing with public input.

Moreover, recommendations by the town’s planning commission to decrease rural minimum lot size from three to two acres was rejected by the North Hero Selectboard. The commission had recommended a more expansive zoning allowance for multi-unit development, but residents convinced the North Hero Selectboard to adopt the more limited area, with density increases in the larger jurisdiction left to a matter of conditional use.

The divergent outcomes in South and North Hero hold important lessons for advocates of restricted growth. In South Hero, advocates lost, but narrowly, demonstrating the near-effectiveness of their organizing and communications efforts. Their network and template of action can be deployed in the next attempt to update their town plan.

In North Hero, a committed group of residents were successful in resisting the most ambitious objective of the growth boosters, which would have adversely affected their quality of life and negatively impacted their island’s environment.

Together, the two cases demonstrate that citizen action can move the needle in opposing growth. The Heros have constructed constituencies for eventual success, if not initial victory.

A Recurring Theme

Chittenden County’s growth struggles pitting the preservation of scenic beauty, rural character and agricultural base against housing development are a recurring theme in counties across the country. Preservationists have traditionally stood up to development interests, but today the latter are joined by “affordable housing” advocates who contend that the demand for housing should be met with more supply—and therefore, that communities need to grow. This is the argument and impetus of easing the current standards of Act 250, and the frame of mind of planners and elected officials who modify zoning.

This clash of interests must ultimately be resolved by means other than accommodating ever more housing if Vermont is to retain its rural character, protect its production of food, and conserve wildlife habitats. While density can play a part in accommodating housing, it should be localized so as not to undermine decades-long efforts to limit land development impacts.

Equal attention should be placed on limiting short-term rentals and the trend of investors buying up housing stock. Efforts to limit these trends probably require federal action.

In the meantime, residents of Vermont have had some success in restraining urban encroachment, serving as examples of steady-state citizenship at the local level.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and Team Leader of the Keep Our Counties Great program at CASSE.

The post Growth Battles in Chittenden County appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

Helping Councils improve key worker housing affordability

Housing affordability is a common topic of conversation across Australia. Taking the case study of Regional Victoria, Nenad takes a look at how rising housing costs impacts an area’s ability to attract and house key workers for that region.

Key worker housing affordability analysis →

Key worker housing affordability: A national problem

Australia’s key workers, that is, workers in services that are essential to a community’s functioning and wellbeing, spend large proportions of their household income on housing costs. The “Priced Out” report, published by Everybody’s Home in April 2023 found key workers on average spending two-thirds of their income on housing as increasing rental costs price them out of their communities.

Workers in aged care, hospitality, freight packing and postal services were among those most impacted, and the report also found there were very few regions in Australia where essential workers could afford to rent alone, while those in coupled homes were probably financially dependent on their partner’s income.

Key worker housing affordability: Regional Victoria case study

Housing affordability is worsening in Regional Victoria, driven by increased demand, shifts in employment dynamics (e.g. working from home/remote work) and COVID-19. Migration from Greater Capital Cities to regions has contributed to increased housing costs, which have raised median house prices to near-Greater Melbourne levels in some parts of Regional Victoria.

Almost 55,000 people living in Regional Victoria in 2021 lived somewhere within Greater Melbourne a year before. In fact, 43% of all people who moved to Regional Victoria from Greater Melbourne in the 2016–2021 period did so in the one year before the 2021 Census.

In December 2023, Regional Development Victoria created the “Regional Worker Accommodation Fund”, a program that allows many entities, including regional local governments, to apply for grants between $150,000 and $5,000,000 for the provision of new housing and accommodation for regional communities where workers in key industries and their families are struggling to find places to live. Further information on eligible projects, funding and the application and outcome process are outlined in the Program Guidelines and frequently asked questions.

Who are key workers?

Key workers are vital to a community’s wellbeing. Although there are no standard definitions of “key worker” occupations, key workers are generally employees in services that are essential to a municipality’s functioning, whose role requires them to be physically present at a work site rather than working from home. Key worker occupations include but are not limited to: waiters, chefs, kitchen staff, commercial cleaners, police, enrolled and mothercraft nurses, doctors, truck drivers, motor mechanics, electricians, welfare support workers and checkout operators.

What is the challenge?

Median house prices in Regional Victoria have increased by 153% since June 2019 and median rental costs by 128%. Both have flattened off in recent months with no indication of significant decline, while other costs of living have also increased, likely resulting in higher levels of housing stress for regional key workers and other Regional Victorian residents.

Keeping key workers close to their place of work is best for the economy and the social fabric of a community but can be a challenge in regional areas, particularly those with high tourism. Housing unaffordability pushes key workers to look for housing further away from their place of work, places of social interaction, support networks, schooling, etc. This can impact a region’s ability to attract or maintain key workers in roles necessary for places to operate and thrive.

What is the role of council?

Local government authorities can take several measures to address housing unaffordability for key workers in their municipality – from challenging long-held assumptions about higher-density developments within local planning considerations (in some cases), to collaborating with State Governments and discussing releasing additional land or engaging constructively in zoning conversations. Councils can also:

- Establish affordable housing as essential infrastructure: Following the recommendation by parliamentary committees, local governments can lead the way in recognising affordable housing as essential infrastructure, prioritising it within their overall infrastructure plans (“Building Up & Moving Out”, 2018).

- Coordinate and collaborate: Local governments should actively engage with State and Federal authorities to develop comprehensive strategies to tackle the affordable housing crisis (ALGA, 2023).

- Explore key worker housing programs: Consider implementing key worker housing affordability programs. Strategies for this can be developed by studying reports and recommendations on declining housing affordability over the years (“Key Worker Access to Home Ownership”, 2018).

- Support national initiatives: Local governments should actively support and participate in national initiatives aimed at improving housing affordability, such as the National Housing and Homelessness Plan (“Developing the National Housing and Homelessness Plan“, 2023).

We encourage councils to get their policies on affordable or key worker housing in order and seek support, partnerships, and grants to address the situation.

How we can help

We’ve worked with several Victorian councils, including the City of Melbourne, to help quantify and understand housing affordability for key workers. The main findings in all previously completed projects were that key workers are vital to a municipality and that some occupations are under much higher housing stress than others, yet housing is becoming less affordable to purchase or rent for most key worker housing groups.

We can support councils looking to obtain funding in various ways:

- Sharing how councils can use their existing suite of .id tools to develop business cases.

- Subscribing to housing.id to build strategies and monitor the ongoing housing situation, including affordability trends.

- Undertaking consulting, such as our Key Worker Housing Affordability report, to quantify key workers in your region, articulate their importance to the local economy and understand whether housing is appropriate and affordable for different key worker groups.

Please contact us for this or any other support.

An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

In the second quarter of 2022, the homeownership rate for white households was 75 percent, compared to 45 percent for Black households and 48 percent for Hispanic households. One reason for these differences, virtually unchanged in the last few decades, is uneven access to credit. Studies have documented that minorities are more likely to be denied credit, pay higher rates, be charged higher fees, and face longer turnaround times compared to similar non-minority borrowers. In this post, which is based on a related Staff Report, we show that banks vary substantially in their lending to minorities, and we document an overlooked factor in this difference—the inequality aversion of banks’ stakeholders.

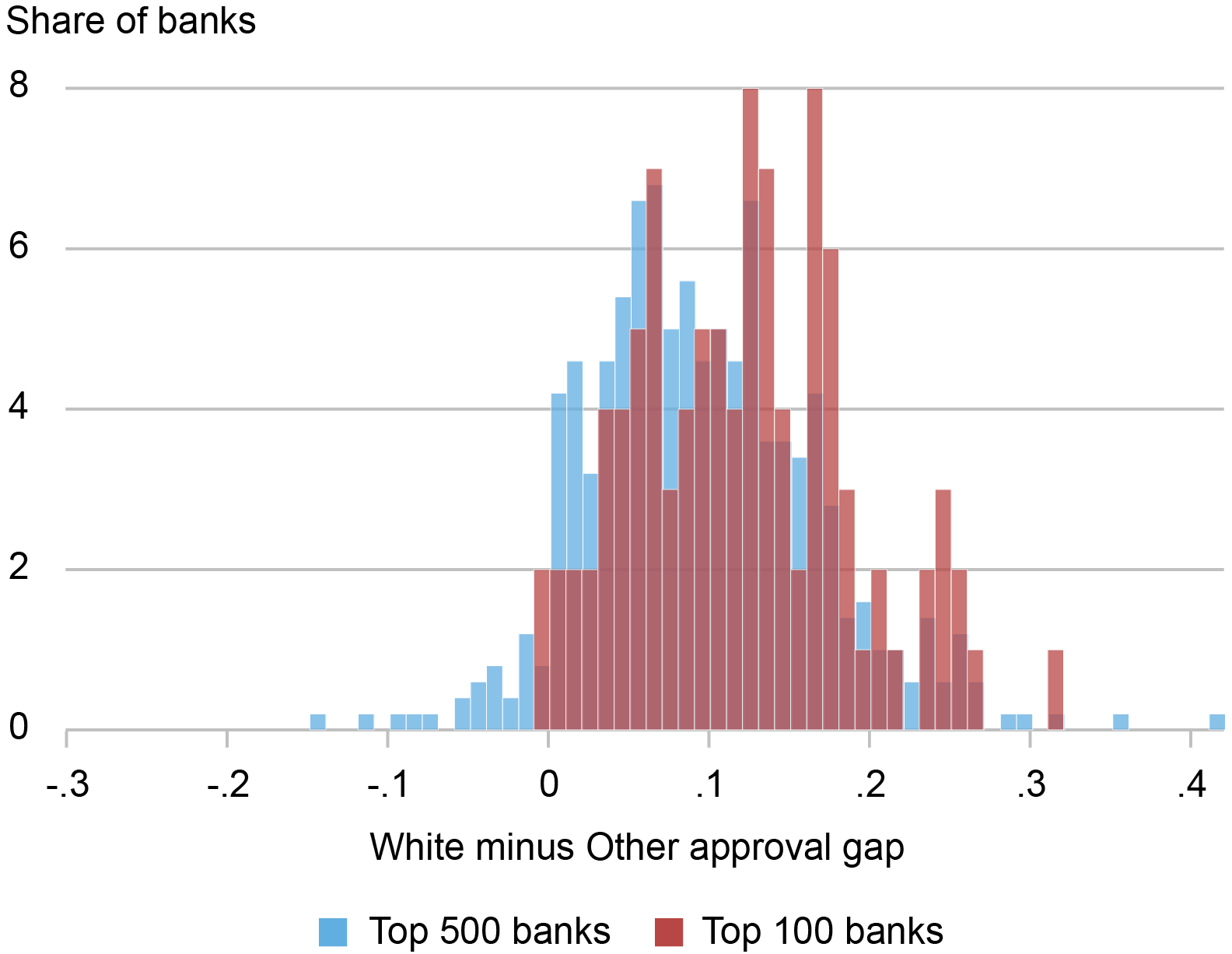

Substantial Differences in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

We use mortgage applications data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act to calculate banks’ lending to minorities. Our data set consists of 114.3 million loan applications received by 838 banks from 1995 to 2019. For each bank and for each year, we calculate the bank approval ratio, defined as the number of mortgage applications approved divided by the number of mortgage applications received.

The difference in lending to minorities across banks is sizable. The chart below shows the distribution of banks’ “approval gaps”—defined as the difference in the approval ratios for mortgage applications made by minority and non-minority borrowers. Such approval gaps tend to be positive (so that approvals are lower for minority applicants) and heterogenous across banks. Crucially, this variation persists within a narrow geographical area (such as county or census tract), suggesting that banks with small approval gaps are not systematically located in areas of the country where minorities have a relatively low credit risk.

Banks’ Lending to Minorities Varies Substantially

Source: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data.

Notes: The chart shows the distribution of approval gaps, defined as the mortgage application approval ratio for white applicants (HMDA race code 5) minus the mortgage application approval ratio for other applicants (HMDA race codes 1-4). Top 500 and top 100 banks are defined based on the number of applications received. The sample period is 1995-2019.

An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities

Measuring stakeholders’ inequality aversion is challenging. It requires both a definition of stakeholders (which include, for example, depositors, borrowers, employees, and executives) and a measure of their preference for equal outcomes, resources, and opportunities. Given that bank stakeholders are mostly local, we calculate bank inequality aversion using a survey question on the desired level of government assistance to minority households from the General Social Survey (GSS), a nationally representative survey conducted since 1972 and widely used in academic studies.

Specifically, we use a survey question that asks whether “we’re spending too much money, too little money, or about the right amount of money on assistance to Black households.” Survey respondents can choose one of these three options, coded with the numbers 1, 2, and 3. We then calculate, for each bank, the weighted average of these responses, using the fraction of deposits that each bank has in the area where the respondent is located as weights.

It’s important to note that our analysis is not based on direct information about any bank’s depositors, board of directors, or management, or anything else specific about a bank other than the location of its branches. In the absence of information about banks’ actual stakeholders, we assume that the inequality aversion of the respondents who live in the area where a bank has a branch presence is representative of the preferences of its stakeholders.

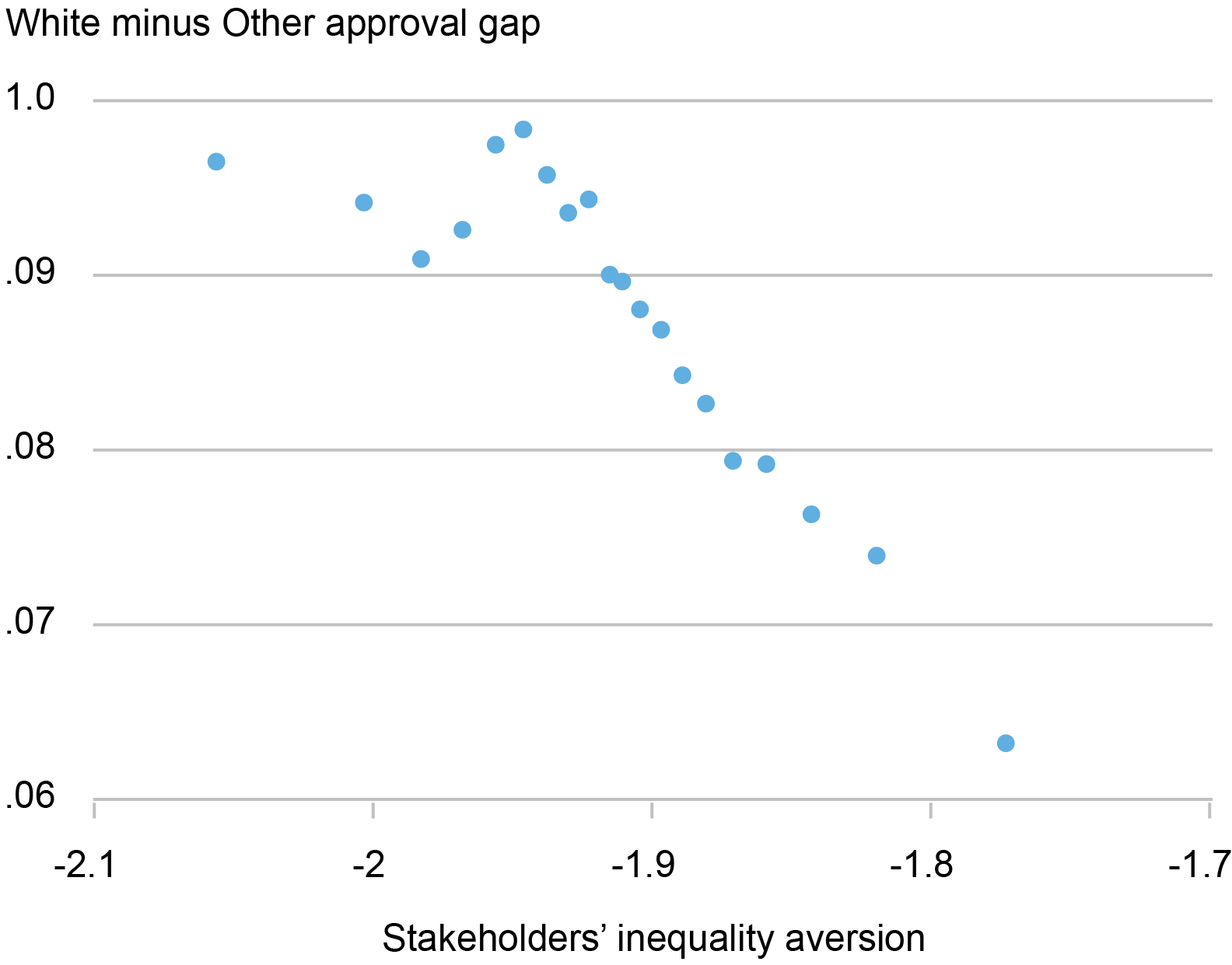

With these caveats in mind, we find that banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders by our measure tend to have smaller approval gaps, as shown in the chart below. The data are analyzed within census tracts, thus ruling out that this negative correlation is entirely due to banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders operating in areas where minorities have a lower credit risk. Similarly, within census tracts, banks with more inequality-averse stakeholders do not systematically receive applications from higher-income minority borrowers, suggesting that minority borrowers with lower credit risk do not systematically apply for mortgages with more inequality-averse banks.

Inequality-Averse Banks Lend More to Minorities

Sources: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data; MIT Election Data and Science Lab; FDIC summary of deposits.

Notes: This binscatter plots banks’ non-minority minus minority approval gaps (the mortgage application approval ratio for white applicants (HMDA race code 5) minus the mortgage application approval ratio for other applicants (HMDA race codes 1-4)) on the y-axis against stakeholders’ inequality aversion (multiplied by minus one) on the x-axis. The analysis controls for census tract–year fixed effects. Banks are grouped in bins for readability.

How Might Stakeholders Affect Banks’ Lending?

So, how might an institution’s stakeholders impact its lending decisions? Likely indirectly. A possible channel is that, in their lending decisions, banks consider the inequality aversion of the counties in which they operate so as to attract and retain their (mostly local) stakeholders. Consistent with this mechanism, we find that banks that have been hit with a Department of Justice (DOJ) case for discrimination in mortgage lending experience a sizable drop in deposits, one that is particularly pronounced in counties with high inequality aversion. This result, detailed in our Staff Report, is consistent with recent anecdotal evidence on how stakeholders’ social considerations affect financial institutions.

Importantly, the higher lending to minorities of banks with inequality-averse stakeholders has a small and positive effect on performance, suggesting that it is not a manifestation of costly “goodness.” Specifically, the narrowing in approval gaps between minority and non-minority borrowers is followed by a small improvement in banks’ mortgage book quality and a small increase in overall bank profitability.

Final Thoughts

Our insight on the interaction between stakeholders’ inequality-aversion and banks’ lending to minorities is related to the discussions about lending discrimination and racial and ethnic disparities in housing. On the one hand, such inequality aversion might alleviate lending discrimination based on race and neighborhood characteristics. On the other hand, it might drive banks to specialize in different segments of the residential mortgage market. One interesting avenue of future research is understanding to what extent credit access for minorities might differ across the country based on the inequality aversion of local stakeholders.

Matteo Crosignani is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Hanh Le is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Illinois Chicago.

How to cite this post:

Matteo Crosignani and Hanh Le, “An Overlooked Factor in Banks’ Lending to Minorities,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 10, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/01/an-overlooked-fact....

Stakeholders’ Aversion to Inequality and Bank Lending to Minorities

![]()

Economic Inequality: A Research Series

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Homelessness among racialized persons

Chapter 7 of my open access textbook has just been released. This chapter focuses on homelessness experienced by racialized persons.

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter can be found here (in English):

https://nickfalvo.ca/homelessness-among-racialized-persons/

A ‘top 10’ summary of the chapter in French can be found here:

https://nickfalvo.ca/litinerance-chez-les-personnes-racialisees/

The full chapter can be found here (English only):

https://nickfalvo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Falvo-Chapter-7-Racializ...

All material related to the book is available here: https://nickfalvo.ca/book/