history

The 9th principle. Meticulous administration.

No Christmas celebration on this blog this year. But a story about communities: the Commons of Buren and Hollum on the Waddensea island of Ameland. Commons have been studied by Elenor Ostrom. Studying Commons is of prime importance: we only have one earth. Reading Ostrom makes one optimistic. One of the things she mentions is the […]

‘A Disunited Kingdom? Britain is Built on Forgetting Our Imperial History’

Newsletter offer

Newsletter offer

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive editorial emails from the Byline Times Team.

Of the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell each other, and the stories the powerful and the political class tell the rest of us, the last one is of particular interest to me. Why?

We know those who control the past control the present. Therefore, the stories we tell ourselves about our past will determine the parameters of what today is considered politically possible and what’s ruled out. And it partly explains, for example, why England can have Brexit but Scotland can’t have independence.

It’s clearly powerful.

Why else do you think the Faragist-right of this country – the intellectual inheritors of Enoch Powell – are so intent on waging and winning their ‘history wars’. It’s because they understand that maintaining the illusory story of what Britain was, is integral to the illusion of what Britain is and the maintenance of their political and economic hegemony.

I switched on BBC News earlier this year to see the Trevelyan family (British aristocrats) apologising and paying reparations to the Caribbean island of Grenada. They were doing so for their ancestors’ part in the enslavement of thousands of Africans – including some of my own ancestors, it transpires, on my father’s side.

It’s led to a podcast, Heirs of Enslavement, which charts the story of Britain’s transatlantic chattel slave trade and plantations, all the way through to today and the continued exploitation of the same people by the same banks and financial institutions that made their money from that brutal exploitation in the first place.

Otto English charts the different strands of English identity over the years and how a dark turn may now be giving way to something altogether more inclusive, decent and inspiring

Otto English

The former BBC journalist Laura Trevelyan, my co-presenter, told me something which stuck in my head because its redolent of a wider truth. She explained how her family had told itself for generations that they were part of the good and the great of British history (the Irish potato famine aside). They were renowned historians, civil service reformers and even Labour Party secretaries of state. But the realisation they had enriched themselves through the longest, most brutal, and exploitative crimes against humanity ever perpetrated, from what I could discern, was like being woken up by a bucket of cold slops; a shock to the system.

But it opened eyes – including my own. It’s allowed me to see that there has been a deliberate forgetting of our history. Whether the usual sanitised story of slavery that focuses on abolition to the assertion that Empire really wasn’t that big a deal (and if it was, well, it brought the rule of law to the world).

A deliberate forgetting. But why?

To cover up a crime scene that spanned the globe and hundreds of years.

To completely disconnect those crimes – and the wealth and power they generated – and how it ended up in the hands of the wealthy, corporations and financial institutions.

Don't miss a story

To enable the construction of a new, national post-Empire narrative of Britain.

Together, I think they help explain a big part of our democratic crisis. 'Britain’ is a construct born of that empire. As post-war decolonisation took place, those sat in the driving seat of Empire PLC needed a new story of what Britain was.

Enoch Powell, the first parliamentarian to embrace neoliberalism – and best known for his Rivers of Blood speech – is less well known for his role in this transformation. In 1950, he exclaimed that "Britain without an empire is like a head without a body".

By the time he wrote his 1965 book, A Nation Not Afraid, he claimed that the Empire was simply an invention that never really happened; that Britain had never set out to conquer the world and that instead it had been landed with the colonies.

Rather, Britain was a pioneering Island where the laws, constitution and systems of government had been unbroken for a millennia. Powell and others gave birth to the lie the British state was born by immaculate conception, then growing organically into the modern day construct we now see. Plucky Britain, so different from its European neighbours.

If that’s the story we tell ourselves then of course the crisis of democracy makes no sense. Its like trying to square observational data of planetary orbits, holding onto the belief the Earth is at the centre of the solar system.

Therefore, this’ forgetting’ is crucial to both the maintenance of the British state as is – the monarchy, the Union, an unwritten constitution, and even our voting system.

It covers up the origins for the gross wealth inequality within our country. Why the city of London, the banks, the financial institutions wield such wealth and power over us. Why a racialised immigration narrative is so deeply embedded into our political culture. Why human rights commitments are now under attack. Why the Union is so fragile.

Everything begins to make sense when we tell ourselves the truth of how we got here. And by doing that, we can better work out what it is we need to do to tackle the crisis of our democracy.

Clive Lewis is the Labour MP for Norwich South. This is an edited version of his speech at the 'Break-Up of Britain? Confronting the UK’s Democratic Crisis’ Conference in Edinburgh on 18 November 2023

‘Those Who Enjoyed the Post-1945 Social Progress of the West Were Made Complacent By It: We Forgot Its Price is Vigilance’

Newsletter offer

Newsletter offer

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive editorial emails from the Byline Times Team.

On New Year’s Day 2024 ‘DEI’ will end at all 33 publicly-funded higher education institutions in Texas. ‘DEI’ stands for ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’ and is the programme aimed at ending racism, sexism and anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination while promoting multiculturalism and inclusion. Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed the anti-DEI Bill into law in June, and already many institutions have dismantled their DEI resource centres and reassigned their staff.

As a move in the culture wars, this is pretty blunt – only one step short of banning people of colour or difference of sexual preferences from campuses outright (people who do not feel welcome will ban themselves; that’s part of the plan), and – in my view – two steps short of lynching them, which was once, and not that long ago, the option of choice in the US’ southern reaches. This fact has to be mentioned because the direction of travel indicated by ending DEI points that unpalatable way – for the simple reason that it’s the direction from which conservative moral thinking comes.

‘Conservative moral thinking’ is a kind way of putting it, because thinking is not what underlies moral conservativism.

What underlies it is feeling: emotions not of empathy and kindness, understanding and acceptance – but of tribalism, xenophobia, racism, fear of change, fear of difference.

Simplistic binaries – white-black, good-bad, male-female, right-wrong – lie at the source and limit of these feelings. Any gradations or nuances upset conservatives and must therefore be stamped on.

One of the major attractions of religion to conservative moralists is that it offers strong rules in relation to anything that does not observe the binaries – the more simplistic the better.

The political wing of conservatism is not, however, quite so unthinking.

ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE? HELP US TO PRODUCE MORE

Receive the monthly Byline Times newspaper and help to support fearless, independent journalism that breaks stories, shapes the agenda and holds power to account.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

From its followers’ point of view, the great inconvenience in life is what they regard as the wrong kind of liberty. Whereas being free from taxes and federal laws, free to carry a pistol and own several assault rifles, free to exploit workers, free to cheat customers, and free to say hateful things about people different from them is the kind of freedom they like – they do not like protests and strikes, people voting in support of their opponents, the law protecting people unlike themselves, and they emphatically do not like paying taxes for other peoples’ health care or education.

This point of view has been frankly and openly voiced in America for decades. But it is only in the last decade or so that this agenda – from 1945 a mostly sleeping virus in Europe’s immune system – has broken through the skin like leprous ulcers in the form of Hungary’s Orbán, Italy’s Meloni, the Netherlands’ Wilders, Austria’s Kickl, France’s Le Pen, Germany’s AfD, and the enablement of the British Conservative Party’s capture by the UKIP/Brexit Party.

The current UK Government has placed limits on protest, set out to ban strikes, introduced mandatory voter ID, shifted billions of pounds from public service budgets into cronies’ pockets, allowed the NHS and local government to wither (so that they can be bought cheap by ‘private providers’ one suspects), protected the Thatcher-sold utility companies with profit-gouging and poor services matched in ambition only by the further billions of debt that have accumulated in order to pay dividends, plan to introduce dozens of ‘freeports’ and ‘special economic zones’ in which private corporations will be effectively be the government and will sell to the local population, for profit, what once were public services – and so wretchedly on, in full asset-stripping, civil-liberty-limiting, anti-democratic mode.

Rishi Sunak attended a gathering in Italy recently, along with Viktor Orbán and Steve Bannon, as a guest of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. Bannon’s presence is significant. The ‘Bannon playbook’ for right-wing politicians is brutal in its simplicity and effectiveness. It is: cause chaos, disrupt, frighten and anger people about immigrants, wokeists, gay people coming for their kids; roil them up; embroil them in difficulties caused by anarcho-capitalism (privatisation on steroids) which makes them paddle faster and harder in the rising waters of debt and insecurity, and put the blame for their plight on the immigrants (mainly) and the wokeists, bien-pensants and ‘liberals’.

Anarcho-capitalism, very bad for the have-nots, is very good for the haves – there’s profit in chaos, lifting bonus caps and selling public assets cheap. While this is going on ‘the state can be rolled-back’ and those pesky civil liberties and democratic restraints that make governing difficult can be ‘disapplied’.

The aim is to reverse the idea that government is the servant of the people’s interests; the people are to be made to serve the governor’s interests. Rulers must rule – without following any rules – and the little people must not get in the way. Their role is to be milked, ceaselessly, mercilessly, impotently.

We see all of this unfolding before our eyes, plain and clear. There is a mighty battle already under way.

Donald Tusk in Poland, Pedro Sanchez in Spain, and Keir Starmer in the UK appear to buck the Bannoning trend. The EU is structured on the progressive and liberal principles of the post-1945 immune time, but in the 2024 European Parliament elections a Bannonish majority might win. Alas: those of us who enjoyed the increasingly open and inclusive social progress of the West after 1945 were made complacent by it; we forgot that its price is vigilance.

The former Home Secretary showed no interest in urgent threats to the UK as the National Security Strategy Committee reveals that Vladimir Putin made attempts to interfere with the last General Election

David Hencke

Though highly allergic to conspiracy theories, I find it ever harder to resist thinking that there might be something to the allegations of a Russian connection with the Bannoning of politics in the democracies of the West. Putin, Orbán, Trump, Republican reluctance to help fund Ukraine’s war, Boris Johnson and the Lebedevs, Russian donations to Britain’s Conservative politicians, Russian interference in elections, Russians murdering Russians on British soil without much consequence – these are a spattering of dots that beckon one to wonder whether they join up.

If there is a connecting line it is to be found in the answer to this question: who stands to gain most by disunity in, even the fragmentation of, Europe? The answer is: Vladimir Putin.

It is a longstanding and well-known aim of his. To some, it is plain that Brexit was his first great success in this endeavour, with the added bonus of considerably weakening the UK itself. The UK, when both in the EU and a strong ally of the US, was once a formidable thorn in would-be resurgent Russian flesh, if you look at it from Putin’s point of view. Now it is a rusting hulk drifting offshore, and the task of picking off others in the convoy is easier.

The connection between moral and political conservatism? Attacks on immigrants and wokeism and the rest do a double job and do it beautifully: they fire up the base, and distract them from the agenda of making them the subjects to an anarcho-capitalist system in which they have few rights, but pay for everything with and beyond their last pennies.

It is not too late to resist what is happening.

Get the UK out of the Putin-helping (whether intentionally or not) Bannoning trend, return to the task of helping to build a strong and Europe committed – as it constitutionally is – to human rights and civil liberties, and resume vigilance thereafter. This is the least we must do.

Controversies over Christmas “Classics”

In Episode 405, Niki, Natalia, and Neil discuss controversies over Christmas “classics.”...

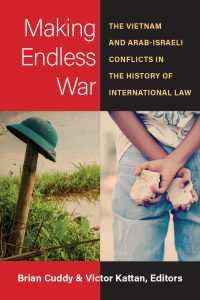

Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law – review

In Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law, Brian Cuddy and Victor Kattan bring together essays exploring attempts to develop legal rationales for the continued waging of war since 1945, despite the general ban on war decreed through the United Nations Charter. Linked through a nuanced comparative framework, the essays in this timely collection show how these different conflicts have shaped the international laws of war over the past eight decades, writes Eric Loefflad.

Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law. Brian Cuddy and Victor Kattan. University of Michigan Press. 2023.

For Jeff Halper, an American-Israeli anthropologist, co-founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and proponent of a single democratic state in historic Palestine, the decision to become an Israeli in the first place had a great deal to do with the Vietnam War. True to the counter-culture protests that arose in response to the War, the activist Halper, like so many young, idealistic American Jews of his era, viewed Israel as a more direct conduit to his heritage than a homogenising suburban upbringing could ever allow for. This search for meaning was coupled with a widespread difference in how the Vietnam War and Israel’s wars were broadly characterised in Halper’s contexts of influence. For many Americans who opposed intervention in Southeast Asia, Israeli violence differed in its “purity of arms.” According to this framing, in direct contrast to an American government waging wars half a world away, Israel zealously fought for its very survival right at its doorstep. It was witnessing the demolition of Palestinian homes to make way for Israeli settlers in the West Bank that caused Halper to renounce this narrative and rededicate his life.

For Jeff Halper, an American-Israeli anthropologist, co-founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and proponent of a single democratic state in historic Palestine, the decision to become an Israeli in the first place had a great deal to do with the Vietnam War. True to the counter-culture protests that arose in response to the War, the activist Halper, like so many young, idealistic American Jews of his era, viewed Israel as a more direct conduit to his heritage than a homogenising suburban upbringing could ever allow for. This search for meaning was coupled with a widespread difference in how the Vietnam War and Israel’s wars were broadly characterised in Halper’s contexts of influence. For many Americans who opposed intervention in Southeast Asia, Israeli violence differed in its “purity of arms.” According to this framing, in direct contrast to an American government waging wars half a world away, Israel zealously fought for its very survival right at its doorstep. It was witnessing the demolition of Palestinian homes to make way for Israeli settlers in the West Bank that caused Halper to renounce this narrative and rededicate his life.

the collection centres on the broad theme of how mostly American and Israeli lawyers, statesmen and military officers used issues that arose in the two conflicts to proclaim exceptions to the general ban on war as entrenched in 1945 through the United Nations Charter.

While Halper’s journey may be a unique one, it is nevertheless a testament to how intersections between post-Second World War conflict in Southeast Asia and the Middle East shaped the lives of so many different people in so many different ways. For anyone interested in how this multitude of individual experiences might be understood in relation to broader systemic forces, especially the variable medium for navigating “legitimate” violence deemed the “laws of war”, historian Brian Cuddy and international lawyer Victor Kattan’s Making Endless War is an invaluable resource. Comprised of ten robust chapters and an insightful forward by Richard Falk (a leading international legal critic of the Vietnam War and later the one-time United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Occupied Palestinian Territories), Making Endless War proceeds on a roughly chronological basis from 1945 to the present day, tracing developments and unearthing connections between the two (meta-)conflicts. With chapters confronting a variety of issues from multiple perspectives, the collection centres on the broad theme of how mostly American and Israeli lawyers, statesmen and military officers used issues that arose in the two conflicts to proclaim exceptions to the general ban on war as entrenched in 1945 through the United Nations Charter. While its detailing of legal doctrine is truly world-class, Making Endless War’s revelation of the individual personalities, diplomatic intrigue and political struggles behind ostensibly “apolitical” technicalities is equally outstanding.

Vietnam, emboldened by its resistance to the US, led efforts in the 1970s to include non-state national liberation movements within a regime of the laws of war that hitherto only granted rights to state actors.

One illustration of how this text accomplishes its multi-faceted, but nevertheless cohesive, focus across chapters concerns the debate on the revision of the laws of war via two Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions. In Chapter Five, Amanda Alexander explores the significance of how Vietnam, emboldened by its resistance to the US, led efforts in the 1970s to include non-state national liberation movements within a regime of the laws of war that hitherto only granted rights to state actors. Following this, in Chapter Six, Ihab Shalbak and Jessica Whyte centre the Janus-faced quality of what this revision meant for the Palestinians. While it provided their cause with a newfound degree of institutional legitimation, it also constrained Palestinian efforts to unite themselves as a revolutionary people whose struggle could not be divided along the lines presumed by the law. From here, co-editor Victor Kattan presents an account in Chapter Seven of how Israel moved from being the sole dissident resisting revision in the 70s (due to its application to the Palestinians) to being joined by the US in the 80s. This coincided with the ascent of the Reagan Administration in the 80s where an influential grouping of Neoconservatives and Vietnam veterans – invoking arguments pioneered by Israel – similarly prevented the US from ratifying the Geneva Convention’s Additional Protocols. Finally, in Chapter Eight, Craig Jones examines how, despite their nations’ disavowal, American and Israeli lawyers became adept at using the laws of war to enable, as opposed to constrain, violence through developing a regime of so-called “operational law” that integrated international and domestic legal standards in a manner “…designed specifically to furnish military commanders with the tools they required for ‘mission success’” (215).

With the ascent of the Reagan Administration in the 80s […] an influential grouping of Neoconservatives and Vietnam veterans – invoking arguments pioneered by Israel – similarly prevented the US from ratifying the Geneva Convention’s Additional Protocols

When reading Making Endless War in this present moment, it is naturally impossible to disconnect its insights from the most recent bloodshed in Israel-Palestine that erupted almost immediately following the collection’s release. Fortuitous in the most horrific way possible, Cuddy and Kattan provide an invaluable service in exposing the impossibly high stakes of the despair invoking “endlessness” that animates their collection’s poignant title. However, by connecting the greater Arab-Israeli conflict to the Vietnam War, the editors make a significant contribution in decentring the widespread viewpoint that the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is fundamentally unique – a presumption that unites pro-Israel and pro-Palestine advocates who agree on virtually nothing else. In this way, Making Endless War provides a powerful statement on how episodes of violence, however specific they might appear, cannot be understood independent of greater forces – including (and perhaps especially) the principles and institutions that present their mission as an effort to constrain armed conflict. As such, Cuddy and Kattan’s collection can be viewed as a major innovation in building a greater genealogy of global violence.

Making Endless War provides a powerful statement on how episodes of violence, however specific they might appear, cannot be understood independent of greater forces – including (and perhaps especially) the principles and institutions that present their mission as an effort to constrain armed conflict.

While their comparative framework might be viewed as limited in its representations, the editors are eminently aware of this, and this very awareness forms a cornerstone of their methodology. On this point, they deliberately confront the significance of how, especially within the centres of global power, “[t]he Vietnam War and the multiple Arab-Israeli conflicts became cultural moments that captured the public imagination in ways few other conflicts did, even those that were more lethal (262).” With this comparative captivation itself an important finding, there is no reason why the insights developed through Making Endless War cannot be extended to include the multitude of other forces, fixations, and personalities that can be located within the many ideologies of war that shape our lives. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is a particularly vast and gut-wrenching repository of said ideologies. Sadly, there is no shortage of material for interested scholars to draw upon.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Michiel Vaartjes on Shutterstock.

Why the Blind Should Lead the Blind

Visually disabled people increasingly turn to institutions and support networks that are created, designed, and implemented by other blind people....

Nikki Haley

In this episode of Past Present, Natalia, Neil, and Niki discuss Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley. ...

History of Gaza: Conquerors, Resurgence and Rebirth

Those unfamiliar with Gaza and its history are likely to always associate Gaza with destruction, rubble and Israeli genocide.

And they can hardly be blamed. On November 3, the UN Development Programme and the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) announced that 45 percent of Gaza’s housing units had been destroyed or damaged since the beginning of the Latest Israeli aggression on Gaza.

But the history of Gaza is also a history of great civilizations and a history of revival and rebirth.

Shortly before the war, specifically on September 23, archaeologists in Gaza announced that four Roman-era tombs had been unearthed in Gaza City. They include “two lead coffins, one delicately carved with harvest motifs and the other with dolphins gliding through the water,” ARTNews reported.

According to Palestinian and French archaeologists, these are Roman-era tombs dating back 2,000 years.

The finding was preceded, two months earlier, in July, by something even more astonishing: a major archaeological discovery of at least 125 tombs, most with skeletons still largely intact, along with two extremely rare lead sarcophaguses.

Archaeologists working on a 2,000-year-old Roman cemetery discovered in Gaza last year have found over 125 tombs, the Palestinian Ministry of Antiquities says. Most of them have skeletons still largely intact and to rare lead sarcophaguses.

(Video: via Reuters) pic.twitter.com/qLZDOnz1qu

— The Palestine Chronicle (@PalestineChron) July 24, 2023

In case you assume that the great archaeological finds were isolated events, think again.

Indeed, Gaza has existed not only for hundreds of years but even thousands of years before the destruction of the modern Palestinian homeland during the Nakba, the subsequent wars, and all the headline news that associated Gaza with nothing but violence.

I grew up in the Nuseirat refugee camp located in central Gaza. As a child, I knew that something great had taken place in Nuseirat without fully appreciating its grandeur and deep historical roots.

For years, I climbed the Tell el-Ajjul – The Calves Hill – located to the north-east of Nuseirat, tucked between the beach and the Gaza Valley – to look for Sahatit, a term we used in reference to any ancient currency.

We would collect the rusty and often scratched pieces of metal and take them home, knowing little about the value of these peculiar finds. I always gifted my treasures to my Mom, who kept them in a small wooden drawer built within her Singer sewing machine.

I still think about that treasure that must have been tossed away following my mother’s untimely death. Only now do I realize that they were Hyksos, Roman and Byzantine currencies.

Once Mom diligently scrubbed the Sahatit with lemon juice and vinegar, the mysterious Latin and other writings and symbols would appear, along with the crowned heads of the great kings of the past. I knew that these old pieces were used by our people who had dwelled upon this land since time immemorial.

The region upon which Nuseirat was built was inhabited by ancient Canaanites, whose presence can be felt through the numerous archeological discoveries throughout historic Palestine.

What made Nuseirat particularly unique was its geographical centrality in the Gaza region, its strategic position by the Gaza coast, and its unique topography. The relatively hilly areas west of Nuseirat and the fact that it encompasses the Gaza Valley have made Nuseirat inhabitable from ancient times to the present.

Evidence of Hyksos, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, and other civilizations that dwelled in that region for thousands of years is a testimony to the area’s historical significance.

When the Hyksos ruled over Palestine during the Middle Bronze Age II period (ca. 2000-1500 BC), they built a great civilization that extended from Egypt to Syria.

So powerful was the Hyksos Dynasty that they extended their jurisdiction into Ancient Egypt, remaining there until the Sea Peoples drove them out. Though the Hyksos were eventually defeated, they left behind palaces, temples, defense trenches and various monuments, the largest of which can be found in the central Gaza region, specifically at the starting point of the Gaza Valley.

Like Calves Hill, Tell Umm el-’Amr – or Umm el-’Amr’s Hill – was the location of an ancient Christian town, with a large monastery complex containing five churches, homes, baths, geometric mosaics, a large crypt, and more.

The discoveries of Tell Umm el-’Amr were recent. According to the World’s Monuments Fund (WMF), this Christian town was abandoned after a major earthquake struck the region sometime in the seventh century. The excavation process began in 1999, and a more serious preservation campaign began in earnest in 2010.

In 2018, the restoration of the monastery itself started. The discovery of the St. Hilarion Monastery is one of the most precious archeological finds, not only in Gaza’s southern coastal region, but in the entire Middle East in recent years.

There is also the Shobani Graveyard, tucked by the sea and located near the western entrance of Nuseirat, the Tell Abu-Hussein in the north-west part of the camp, also close to the sea, along with other sites, which are of great significance to Nuseirat’s past.

A Gaza historian told me that it is almost certain that Tell Abu Hussein was of some connection to Sultan Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi’s military campaign in Palestine, which ultimately defeated and expelled the Crusaders from the region in 1187.

The history of my old refugee camp is essentially the history of all of Gaza, a place that played a significant role in shaping ancient and modern history, its geopolitics, and its tragic and triumphant moments.

What is taking place in Gaza now is but an episode, a traumatic and a defining one, but nonetheless, a mere chapter in the history of a people who proved to be as durable and resilient as history itself.

Feature photo | A Palestinian man sweeps dust off parts of a Byzantine-era mosaic floor uncovered by a farmer in Bureij in central Gaza Strip, Sept. 5, 2022. Fatima Shbair | AP

Dr. Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of six books. His latest book, co-edited with Ilan Pappé, is ‘Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak Out’. His other books include ‘My Father was a Freedom Fighter’ and ‘The Last Earth’. Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net

The post History of Gaza: Conquerors, Resurgence and Rebirth appeared first on MintPress News.

Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback” (guest post)

“The proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we sometimes need to look at what that victim has suffered in the past, and whether we’re responsible for what they’ve suffered” as well as “whether we should have acted differently in the past thereby avoiding the need to inflict that harm now.”

In the following guest post, Saba Bazargan-Forward (UC San Diego) argues that these backward-looking elements imply that “we should not adopt an ‘ahistorical’ approach when adjudicating proportionality in Israel’s war against Hamas”

It is part of the ongoing series, “Philosophers On the Israel-Hamas Conflict“.

[Paul Apal’kin, “Invasion”]

Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback”

by Saba Bazargan-Forward

Hamas’ attack against Israeli civilians on October 7th, 2023 was not just an act of terrorism but an act of genocide, and should be condemned as such. The brutal attack was shocking in its scope and sadism. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that attacks from Hamas are generally foreseeable consequences of unjust policies Israel has imposed upon Palestinians in Gaza over the past few decades. This supposition, even if true, does not lend moral legitimacy to Hamas’ terrorism. Nor does it mitigate the culpability of Hamas’ leadership. But it does raise this question: if Hamas’ terrorism is “blowback” from unjust Israeli policies toward Gaza, does this affect how Israel is permitted to fight back? Here, I address this question.

War ethics, both in its canonical form and in its more recent revisionary derivations developed since the turn of the century, tends to focus on “the moment of crisis”—the point in time at which a state is seriously considering a resort to war. The problem with assessing the morality of war at the moment of crisis is that sometimes the state considering a resort to war is partly responsible, by having committed past wrongs, for creating the situation in which a resort to war becomes necessary in the first place.

It seems to me that there are at least two special moral considerations restricting how these “blowback” conflicts should be fought, which, in turn affects whether such conflicts can be fought. (I discussed this issue in an article where I focused on the relevance of compensation; here, I consider other factors.)

The first moral consideration relevant to evaluating “blowback” conflicts is this: if Israel has unjustly immiserated Gazan civilians in the recent past, then the collateral harm Israel inflicts in its current war against Hamas harms civilians in Gaza twice over. This is relevant to the comparative weight that these harms should receive when deciding whether to inflict such harms. It is relevant because harming people whom you have already wrongfully harmed is harder to justify than harming people you have not.

To see this, imagine that Rescuer can prevent Innocent from being murdered only by collaterally breaking another innocent person’s arm: person A or person B. They’re identical, except that Rescuer wrongly broke A’s arm last year. If Rescuer chooses the action that collaterally harms A now, she will have thereby infringed A’s rights twice, whereas if she chooses B now, she will have thereby infringed B’s rights once. Since the former is morally worse than the latter, it seems Rescuer should choose B over A. There is a way out: Rescuer could permissibly flip a coin in deciding whom to choose, provided she will compensate A for the independent past harm. But assuming Rescuer won’t compensate A, it seems to me that A has a stronger claim than B against being harmed. A corollary to this claim is that the harm averted to Innocent must be greater to justify breaking A’s arm than B’s arm.

Some might demur. To see why, consider a variant of the case in which the details are the same, except there’s no person B. So, the only way to rescue Innocent is by collaterally harming A. It might seem strange to think that Innocent’s claim to be saved can depend on whether Rescuer unjustly harmed A in the past. After all, Innocent didn’t have anything to do with Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A. Yet it now seems that Innocent must bear the costs of that mistreatment! That seems unfair. It’s true that Innocent’s claim to be saved does not depend on whether Rescuer unjustly harmed A in the past. But it’s also true that Innocent’s claim does indeed depend on the weight of the prospective harm Rescuer will collaterally inflict on A. And I’m suggesting that Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A can affect how we should weigh the prospective harm that Rescuer will collaterally inflict on A in saving Innocent. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that Rescuer shouldn’t save Innocent. Rather, it means that Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A is morally relevant in the decision whether to save Innocent by harming A.

Let me clarify what I’m not claiming. I am not claiming that we always have decisive reasons to prefer harming those we haven’t unjustly harmed in the past over those we have unjustly harmed in the past. There are all sorts of factors that might outweigh or override the relevance of past harms. Rather, I am claiming that past unjust harms can be morally relevant in evaluating prospective harms. I am also not claiming here that past unjust harms for which you’re not responsible are relevant in weighing prospective harms. Though I do certainly think such harms can be relevant, I am not leaning on such a claim here.

This simplistic example in which you must choose between A and B is not meant as an analogy of the situation between Israel and Gaza. Rather, its purpose is more general. It suggests that the proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we sometimes need to look at what that victim has suffered in the past, and whether we’re responsible for what they’ve suffered. If Israel has indeed unjustly immiserated Gazans over the past few decades, this makes it harder for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint now in its current conflict in Gaza.

The second moral consideration relevant to evaluating “blowback” conflicts is this. Assuming Hamas’ terrorism was a foreseeable consequence of unjust Israeli policy toward Gazans, Israel bears some responsibility for the fact that it needs to resort to self-defense now. (Again, I am not claiming that responsibility is zero-sum—Israel’s responsibility for its situation does not diminish Hamas’ responsibility. Nor am I claiming that they are equally responsible, or that they are the only parties responsible). This means Israel bears more responsibility for the deaths of Gazans it collaterally kills than it otherwise would. To see this, imagine you have a neighbor who for no reason at all unjustly attacks you with the intention of breaking your arm. You can defend yourself, but only by engaging in an action that collaterally harms his young child. Now compare this with a nearby case. Imagine you have a neighbor whose car you unjustly vandalize. You suspect, prior to doing so, that in response he will unjustly attack you with the intention of breaking your arm. Again, you can defend yourself, but only by collaterally harming his young child. Holding all the harms fixed in these two cases, it seems that the harm to the child in the second case should be weighed more heavily than the harm to the child in the first case. This is because you can be morally expected to have avoided the harm in the second case but not the first.

Again, this simplistic example is not meant as an analogy of the situation between Israel and Gaza. Rather, it suggests that the proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we need to look at whether we should have acted differently in the past thereby avoiding the need to inflict that harm now. If this describes Israel’s situation currently, it makes it all the more difficult for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint.

The moral is that we should not adopt an “ahistorical” approach when adjudicating proportionality in Israel’s war against Hamas. This is because the proportionality constraint includes important backward-looking elements. If Hamas’ terrorism is “blowback” from unjust Israeli policy toward Gaza, then Gazan lives should be weighed especially heavily. This, in turn, makes it more difficult for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint in its conflict against Hamas.

The post Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback” (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

Nature, Wild Girls, and Putting History in a New Environmental Perspective

In her latest book, Wild Girls, Harvard historian Tiya Miles is particularly concerned with how the relationship with nature established by several nineteenth-century women—some prominent, some not—helped them flourish outside of conventional gender roles. ...