history

The Politics of Time: Imagining African Becomings – review

The Politics of Time: Imagining African Becomings, edited by Achille Mbembe and Felwine Sarr, stems from the second “Workshops of Thought” held in Dakar in 2017, which brought together African and diasporic intellectuals and artists to discuss topics from decolonisation to political transformation. Engaging variously and critically with African life and thought, Camila Andrade finds this interdisciplinary volume a vital tool for reimagining the continent’s future.

What word or image comes to mind when you think about Africa? What academic and non-academic texts reflect (on) the African reality? Are they by African writers living on the continent or diaspora? The Politics of Time: Imagining African Becomings, edited by Achille Mbembe and Felwine Sarr, makes it possible to reflect on themes pertinent to the African experience that create future and imaginary possibilities beyond the stereotypes attributed to Africa.

What word or image comes to mind when you think about Africa? What academic and non-academic texts reflect (on) the African reality? Are they by African writers living on the continent or diaspora? The Politics of Time: Imagining African Becomings, edited by Achille Mbembe and Felwine Sarr, makes it possible to reflect on themes pertinent to the African experience that create future and imaginary possibilities beyond the stereotypes attributed to Africa.

Considering Africa involves grappling with a diverse, dynamic and thriving continent, with significant economic growth and a growing youth population. It also involves analysing its problems – such as the levels of inflation, the impacts of climate change, hunger and malnutrition – that have coincided with young post-independence states. It is noteworthy, not to mention ironic, that terms such as “failed states” and “Frankenstein states” are used considering that these African states entered the international scene at a radical disadvantage after being exploited by their former colonisers. From this historical scenario, it is essential to analyse the continent’s past and repoliticise time. And as Mbembe, Sarr and the authors in this volume demonstrate, this endeavour is crucial in the context of conceptualising Africa’s future.

It is essential to analyse the continent’s past and repoliticise time. And as Mbembe, Sarr and the authors in this volume demonstrate, this endeavour is crucial in the context of conceptualising Africa’s future.

The book’s title presents a reflection on the possibilities of plural times, since “[…] we are witnessing the emergence and crystallisation of a new cycle in the redistribution of power, resources, and value” (ix) in the world, as Mbembe and Sarr argues in the preface. There are different moves at a multiplicity of speeds, continuities and ruptures in time, which lead us to think about future possibilities for Africa. “Imagining African becomings” means recognising its past, understanding its present and conjecturing possibilities for the future. The continent has been gaining space in the international arena, whether by acting in international organisations, through the African Union and its regional economic zones, or by its individual state roles. Therefore, Mbembe and Sarr claim that “Africa is not merely the place where part of the planet’s future is currently playing itself out. Africa is one of the great laboratories from which unprecedented forms of today’s social, economic, political, cultural, and artistic life are emerging” (viii).

The book is divided into six parts, in addition to the preface, bringing together intellectuals from different areas who adopt different lenses on Africa’s history and future possibilities, both academic and non-academic, covering law, literature, anthropology and others. The sections comprise 20 chapters with fundamental and urgent themes, such as the movement of people, migration, religion, the African diaspora, African futures and decolonial African education.

The book is the result of “The Workshops of Thought” (Les Ateliers de la Pensée) held in Dakar in 2017, an initiative created by the editors to unite intellectuals to think about plural perspectives of Africa’s realities and its possible futures

The book is the result of the second “Workshops of Thought” (Les Ateliers de la Pensée) held in Dakar in 2017, an initiative created by the editors to unite intellectuals to think about plural perspectives of Africa’s realities and its possible futures. The first session, held in October 2016, produced the volume To Write the Africa World, of which The Politics of Time is a companion. The Ateliers initiative demonstrates the vitality of intellectuals in African Studies, especially those working in Africa and its diaspora, who aim to deconstruct myths about Africa and go beyond that with “[…] the freedom to imagine alternatives” (135), as Françoise Vergès offers in the chapter “Un/learning”.

The chapters are developed based on the guiding question of how to envision a politics of time in contemporary conditions (ix). Other relevant questions are posed for reflection throughout the chapters, such as: “How might one transform the present and the past into a future? How might one produce a bifurcation in the real? Imagine other African possibilities? […] These, we suspect, have been the questions at the heart of the modern study of Africa and its diasporas” (x-xi).

Reflecting on possible futures also involves the decolonisation of knowledge; that is, thinking about practices, methodologies and objectives that prioritise the needs of the African continent. Universities and other educational apparatuses are not neutral: they were and continue to be instruments of (neo)colonising ideals. It is important to have an education that frees the body and mind and that goes beyond the reproduction of Eurocentric models that elide realities not found in Western universality. As Souleymane Bachir Diagne argues in the chapter, “From Thinking Identity to Thinking African Becomings”, “Today, the principal form of Eurocentrism is not one culture’s assertion that its values can dictate the norms that all others must follow. It is, rather, the form that grants the West the exorbitant privilege of being the only culture capable of reflecting critically of itself” (8).

Imagining possible futures for Africa also involves having different narratives and a plurality of stories. It requires us to rethink political models and the nation-state model itself, imported by colonisation. As Felwine Sarr argues in the chapter, “Reopening Futures”,

“It is about leaving behind the Eurocentrism tied to linear, progressive schemas of History, and of dropping Europe’s master-narrative, whose model the world’s other peoples are condemned to adopt or unhappily repeat. It is about accepting the plurality of collective ways of being, the multitudinous forms of societal life, the diverse modalities for producing being that we call cultures – and it is about accepting the possibility of there being many worlds within the world” (119).

In Amefrica Ladina we are also undergoing a decolonisation of knowledge, and it is vital to exchange ideas and methods with our peers in the Global South on how we can envision prosperous futures.

In the chapter “Weaving, a Craft for Thoughts”, Jean-Luc Raharimanana reminds us that “Successive centuries of domination block the free narration of our relations with the world, but, in the end, those times were unable to efface us from the society of the Living [des Vivants]. Africa is here; Africa is in us” (49). As part of the African diaspora, geopolitically located in the Global South (Brazil), the connection between Africa and its diaspora caught my attention throughout the article, understanding the role of the latter in terms of society, development, history and ancestral connectivity. In Amefrica Ladina we are also undergoing a decolonisation of knowledge, and it is vital to exchange ideas and methods with our peers in the Global South on how we can envision prosperous futures.

In thinking through the means of creating these futures, the book becomes a fundamental tool for intellectual emancipation about and for Africa. It provides a rich overview of the ideas and challenges for thinking about multiple Africas contemporaneously. Just as the African Union’s Agenda 2060 presents its vision as “an Africa for Africans and by Africans”, The Politics of Time inspires us to go beyond a static future premeditated by outsiders, instead imagining utopian futures that can become realities.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image: Red Block, 2010 by Ghana born artist El Anatsui, on show at The Broad, Los Angeles; October 2022. Credit: █ Slices of Light  █▀ ▀ ▀ on Flickr.

█▀ ▀ ▀ on Flickr.

The Little Prince Haunts New York

When I moved to New York, I set out to discover how my new adopted home had influenced that sense of tristesse in The Little Prince, which Saint-Exupéry wrote during his 1941–1943 stay in the city....

Nine recommended reads for Women’s History Month 2024

To celebrate Women’s History Month 2024, LSE’s librarian for Gender Studies Heather Dawson recommends nine books written by, and examining the lives of, inspiring women.

As LSE’s Gender Studies librarian, it is my great pleasure to introduce some of my highly recommended books from our collection for Women’s History Month. I hope you find them educational, thought-provoking and inspiring.

During March, look out for the links I will be posting on X and Instagram to other recommended resources available via LSE Library, including databases of articles and primary resources. LSE staff and students can book one-to-one advice sessions for further help researching women’s history resources.

LSE is privileged to be the custodian of the magnificent Women’s Library, an archive which includes extensive materials relating to the struggle for the vote. My first choice highlights the way in which visual imagery was used as an important part of the campaign. It includes information on key organisations and discussion of creative art as an expression of protest.

For serious researchers of suffrage history, I would strongly recommend any of the reference works by Elizabeth Crawford as key starting points. Her latest book is an invaluable reference for tracing accurate information about the lives of women artists who supported the campaign for the vote in Britain. It also includes some fantastic photographs! You can explore some of the images on the LSE Library Digital Library, including a section on suffrage banners.

Another highlight of the women’s library collection is its selection of biographies of famous and inspiring women. Fans of the Gentleman Jack BBC TV series will be interested to know that we have recently obtained a copy of As Good As a Marriage, an annotated selection of excerpts from the diaries of Anne Lister, a landowner from Yorkshire considered by some as “the first modern lesbian.” This latest volume by historian Jill Liddington focuses on the Lister’s “marriage” to heiress Ann Walker whom she lived with in Shibden Hall, near Halifax. Hear Dr Liddington speak about the book at an event with LSE Library on Wednesday 20 March at 6.00pm.

Another recent edition from a great friend of The Women’s Library, Jane Grant focuses on the life of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. In 2018 one of the LSE towers was renamed in her honour to recognise her contribution to the struggle for women’s suffrage.

The title refers to the fact that she is often overshadowed by her contemporary in the Women’s Social and Political Union, Emmeline Pankhurst. However, Pethick-Lawrence’s achievements, alongside her husband, in founding the newspaper Votes for Women and in continuing to campaign for equal rights for women during the 1920s and1930s as part of the leadership of the Women’s Freedom League should not be forgotten.

A Woman in History: Eileen Power, 1889-1940. Maxine Berg. Cambridge University Press. 2023.

A Woman in History: Eileen Power, 1889-1940. Maxine Berg. Cambridge University Press. 2023.

Of course, the collection includes biographies of famous LSE staff and alumni. A key example is that of economic historian Eileen Power who was appointed as a Chair in Economic History at LSE in 1931 and was influential in founding the Economic History Review journal as well as in developing children’s radio broadcasting on historical topics. As she died young, the most well-known biography of her life is now quite old, written by Maxine Berg.

However, I was fascinated to see her included in a recent joint biography. Power is considered alongside Virginia Woolf, detective writer Dorothy L Sayers, classical scholar Jane Harrison, and modernist poet HD, who all lived nearby Mecklenburgh Square at some time from the 1920s to the 1950s. Find out more about their trailblazing (and often glamourous) lives in this recording from a 2020 LSE Library.

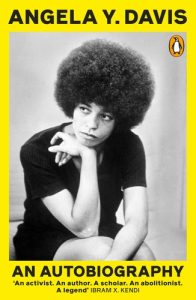

Angela Davis: An Autobiography. Angela Y Davis. Hamish Hamilton. 2022.

Angela Davis: An Autobiography. Angela Y Davis. Hamish Hamilton. 2022.

Our biographies concentrate on both well- and lesser-known figures. One which I personally recommend for her sheer endurance in the face of adversity is the renowned Angela Davis. Davis, an American political activist and academic has been involved in struggles faced by Black people, women and LGBTQ+ communities for decades.

A lesser-known figure I was astounded to discover via a BBC radio documentary was Dorothy “Dorf” Bonarjee: the first Asian woman to win the Bardic chair in 1914 for poetry at Eisteddfod, University College of Wales for verse submitted under a pseudonym. Her achievement was even more astonishing considering at the time women needed a chaperone to attend lectures. Examples of her poetry have been collected in this recent volume edited by Mohini Gupta and Andrew Whitehead.

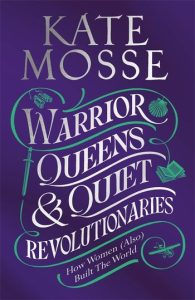

Warrior Queens & Quiet Revolutionaries: How Women (Also) Built the World. Kate Mosse. Mantle. 2022.

Warrior Queens & Quiet Revolutionaries: How Women (Also) Built the World. Kate Mosse. Mantle. 2022.

Finally, I suggest Kate Mosse’s Warrior Queens & Quiet Revolutionaries. This is a good book to dip into to get a sense of the sheer number of influential women worldwide who made significant political, cultural and economic impacts during their lifetimes, but are now often overlooked. During this month, you can explore the padlet I will be developing based on the book’s selection of notable women.

Note: This reading list gives the views of the author and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

The Commons of Ameland: An Uncommon History.

There is no ‘tragedy of the Commons.’ But a tragedy of the absence of Commons-as organizations, let’s call it ‘the tragedy of uncommons’, does exist. Below, I will provide the example of the island of Ameland in the Northern Netherlands, in line with the historical examples of successful Commons mentioned by Elinor Ostrom (especially those […]

The world of bullshit we’ve built: Reflections on a scene from Utopia

I recently took my son to the stage play of Yes, Prime Minister. … The decades have made a huge difference in the sensibility of the new production … . The series ran through most of the 1980s, a period that contained its share of tumult. … But somehow the dramas were genteel, reflecting battles between those privileged enough to be in the system. Waste in government continued, powerful people and time-servers were protected when they should have been exposed and dealt with. But one could be forgiven for thinking, at the end of an episode, ‘it was ever thus’. 1 on, as the moral dilemmas piled up in the stage-play, the governors conspired against the governed.

It’s hard to put one’s finger on it, but to speak loosely, I’d say that when I joined the workforce fifty-odd years ago, life inside that workforce was about 80% the lifeworld — just getting on with people, doing one’s job whatever it was. I was in Canberra and got a holiday ‘bridging’ job in the ACT over the summer hols. I was part of a small team administering rebates to people on their public housing rent for various reasons of need. (Rosemary who I was assisting was a very nice person and had loved being a nurse. She didn’t love this, but it was OK and it paid better.) In any event, although it was administrative, it was still a concrete system, not unlike running public transport or a newsagent. At least inside the beast, you could tell whether anything too silly was being done.

The other 20% was, if you like ‘the system of the system’ which hierarchies are preoccupied with. Reports to superiors and so on, though given how concrete what one was doing was, this worked reasonably well. I guess it wouldn’t be hard to find stories of fairly comprehensive waste to protect some superior’s view of things. But there was little high farce of the kind so beautifully sent up in Utopia.

I’d never accuse this world of being ‘high performing’. It was quite mediocre, but it was human, it muddled through, one wasn’t encouraged to have tickets on yourself. There was a tea lady of some standing who came round every morning and afternoon. Nor do I want to suggest that such an office wouldn’t contain antagonisms — perhaps quite deep ones. But there was quite an ethic of getting on and helping out. And that contributed to a deep kind of egalitarianism. Seniority was respected but not fawned over. And commonsense was a strong anchor in life.

Fast forward to today and the degree of farce is just off the charts. At the tail end of the world I’m describing, we did away with national anthems beginning movies and toasts to the Queen at the very most pompous events. Now everything is populated with new pieties. Each meeting — often each speech given at a function — is preceded by an acknowledgement of country. People are constantly involved in farcical activities — of the kind satirised in Utopia.

Almost certainly their workplace operates with a whole anti-thinking apparatus up in lights — mission and vision statements and ‘values’ statements. If you’re at one of these events it is not a good move, for your blood pressure, your self-respect or your career to say that you don’t think that the values of an organisation can be written in a list hung in the foyer — that values aren’t like that. That values might have names in our language, but they are present in our lives as choices.

Now even after fifty years of development such things still don’t take up that much time. But they are central to the official governance of the organisation. I don’t think of them as causes so much as symptoms of something much deeper. They’re the tip of a large iceberg in which;

- What is said and what is done within and by organisations are able to float pretty much freely away from each other;

- There was always plenty to object to in the worlds of mainstream politics and media, but today they are mostly infantile — including most ‘quality’ media coverage of politics which is glorified racecalling.

- Government reports are full of bland-out — pleasing words “improve”, “reform”, “sustainable”, “accountable”, “transparent” and on and on, and only someone who wasn’t paying attention thinks those words mean what they say. They could mean what they say, they could mean the opposite. Unless I’m deep in some issue, I don’t read government reports because they can’t be understood without being an insider. The same goes for corporate reports. And come to think of it, would you get much more than a fairly predictable schtick from the annual report of a major NGO?

- Back then, discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation could live a fairly robust existence within the ‘commonsense’ of the workplace and this was obviously a very bad thing. So in major respects things are better than that today. We also go after things like bullying in the workplace. And there’s a lot of it about. So going after it is certainly a laudable goal. But it’s a very difficult goal and we don’t proceed as if it were. The upshot is that we’re giving lots of power to people who can game such systems — bullies in fact. Should we give up on anti-bullying? I’d hope we wouldn’t need to, but I think it’s quite likely that — perhaps after a few years where the new arrangements help a little — the systems become gamed by bullies so badly that they do more harm than good. Have we set these systems up to help us know if things are going awry? Nope. We’ve set them up as we always do — as elaborate role plays with accountability theatre to the higher-ups. What could possibly go wrong?

- These dot points are just that — a few scattered thoughts. Many more phenomena could be itemised — perhaps I’ll do that as they occur to me.

I won’t claim to be able to articulate it much beyond what I’ve said here. It’s bugged me that I can’t do better for ages, but watching the Utopia clip above spured me to note it, because, it’s trying to make a similar point.

- A generation

Submarines then and to come

The multi-billion dollar expenditure on nuclear powered submarines as part of the AUKUS pact has attracted some attention. Perhaps it helps to provide historical context if it is remembered that Australia’s first submarines were of limited use in the defence of our shorelines. My four times great grandfather William Eckford from North Ayrshire was a Continue reading »

EP Thompson's break with Stalinism

E. P. Thompson was one of the great social historians of the twentieth century (link, link). He was also a committed socialist from youth to the end of his life. His 1963 book, The Making of the English Working Class, transformed the way that historians on the left conceptualized “social class”, and it was one of the formative works of "history from below". Thompson was a member of the British Communist Party (CPGB) until 1956, following the Soviet invasion of Hungary and Nikita Khrushchev"s "secret speech" revealing some of Stalin's crimes. Thompson remained a staunch advocate of English socialism throughout his life. But as a Communist, he showed an unwelcome degree of intellectual and political independence, and he broke with the CPGB very publicly in 1956 with a manifesto criticizing the party leadership, “Winter wheat in Omsk” (Thompson 1956) and “Socialist humanism” (Thompson 1957). Christos Efstathiou describes Thompson (along with John Saville and Lawrence Daly) in these terms:

What united these three men, and, at the same time distinguished them from other Communist dissidents, was that they did not hesitate to fight the Party’s policies. (Efstathiou 2016: 29)

Consider Thompson’s break with Stalinism in “Socialist humanism” (1957; link). The essay is decisive in rejecting Stalin’s “ideology” and his bureaucratic dogmatism and domination of the whole of society. Thompson writes eloquently about the need within socialism for open debate and discussion. But the essay does not give primary emphasis to the crimes of the Stalinist state: the Holodomor, the purges, the Show Trials, the Gulag, or the pervasive totalitarianism created by the Soviet state. Thompson does refer to “monsters of iniquity like Beria and Rakosi” and mentions their crimes – “destroying their own comrades, incarcerating hundreds of thousands, deporting whole nations”. And he gives a short summary of the show trial of the Bulgarian Communist leader Traicho Kostov. (The narrative is worthy of Koestler in Darkness at Noon.) Here is how Thompson writes about travesties like the trial of Kostov (and, presumably, the better known trials of Bukharin, Zinoviev, and other Bolshevik leaders):

We feel these actions to be wrong, because our moral judgements do not depend upon abstractions or remote historical contingencies, but arise from concrete responses to the particular actions, relations, and attitudes of human beings. No amount of speculation upon intention or outcome can mitigate the horror of the scene. Those moral values which the people have created in their history, which the writers have encompassed in their poems and plays, come into judgement on the proceedings. As we watch the counsel for the defence spin out his hypocrisies, the gorge rises, and those archetypes of treachery, in literature and popular myth, from Judas to Iago, pass before our eyes. The fourteenth century ballad singer would have known this thing was wrong. The student of Shakespeare knows it is wrong. The Bulgarian peasant, who recalls that Kostov and Chervenkov had eaten together the bread and salt of comradeship, knows it is wrong. Only the “Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist” thinks it was – a mistake. (119)

Elsewhere in the text Thompson refers to "British socialists who see men who claim ‘Marxism’ as their guide, banner, and ‘science’ perpetrating vile crimes against their own comrades and gigantic injustices against many thousands of their fellow men". By "British socialists" he means primarily the group of former communist intellectuals who left the British communist party in 1956 and contributed to efforts to create a new Left labor movement in Britain through the New Reasoner and various new organizations. And here he is explicit in mentioning the "crimes and gigantic injustices" committed by the Stalinist state.

But these points about Stalin's crimes are incidental, not focal to Thompson’s critique of Stalinism. Thompson’s actions and words in 1956 reflect a revolt against “dogmatism” and the effort of the Party to control thought and debate. But his critique does not extend to a thorough-going indictment of the crimes committed by the Stalinist state. The murders and injustices to which Thompson refers here seem to encompass the terror and show trials of the 1930s, though Thompson is not explicit. But I do not find anywhere in his writings an explicit recognition of the atrocities of collectivization and the Holodomor in 1932-33. Reference to the Gulag appears in later writings (for example, in a passage quoted below from "The Poverty of Theory"). But, once again, Thompson does not provide a sustained and thorough critique of these crimes against individuals and groups by the Soviet state. Rather, the central focus of his critique of Stalinism in "Socialist Humanism" is the dogmatism and ideological purity demanded by the Stalinist state.

This is – quite simply – a revolt against the ideology, the false consciousness of the elite-into-bureaucracy, and a struggle to attain towards a true (“honest”) self-consciousness; as such it is expressed in the revolt against dogmatism and the anti-intellectualism which feeds it. Second, it is a revolt against inhumanity – the equivalent of dogmatism in human relationships and moral conduct – against administrative, bureaucratic and twisted attitudes towards human beings. In both sense it represents a return to man: from abstractions and scholastic formulations to real men: from deceptions and myths to honest history: and so the positive content of this revolt may be described as “socialist humanism.” It is humanist because it places once again real men and women at the centre of socialist theory and aspiration, instead of the resounding abstractions – the Party, Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism, the Two Camps, the Vanguard of the Working-Class – so dear to Stalinism. It is socialist because it re-affirms the revolutionary perspectives of Communism, faith in the revolutionary potentialities not only of the Human Race or of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat but of real men and women. (Thompson 1957: 108)

Thompson framed his critique of Stalinism somewhat more pointedly two decades later in his polemical essay against Althusser, “The Poverty of Theory” (1978) .

We are not only (please remember) just talking about some millions of people (and most of these the ‘wrong’ people) being killed or gulaged. We are talking about the deliberate manipulation of the law, the means of communication, the police and propaganda organs of a state, to blockade knowledge, to disseminate lies, to slander individuals; about institutional procedures which confiscated from the Soviet people all self-activating means (whether in democratic modes or in forms of workers’ control), which substituted the party for the working class, the party’s leaders (or leader) for the party, and the security organs for all; about the confiscation and centralisation of all intellectual and moral expression, into an ideological state orthodoxy — that is, not only the suppression of the democratic and cultural freedoms of ‘individuals’: ... it is not only this, but within the confiscation of individual ‘rights’ to knowledge and expression, we have the ulterior confiscation of the processes of communication and knowledge-formation of a whole people, without which neither Soviet workers nor collective farmers can know what is true nor what each other thinks. ("The Poverty of Theory or an Orrery of Errors", Thompson 1978: 328-29)

Here Thompson is more explicit in naming the crimes of the Stalinist state -- mass murder, the Gulag. But here too Thompson seems most concerned about the dogmatism and thought control of the Stalinist state, "the suppression of the democratic and cultural freedoms of 'individuals'".

Stalinism, in its second sense, and considered as theory, was not one ‘error’, nor even two ‘errors’, which may be identified, ‘corrected’, and Theory thus reformed. Stalinism was not absent-minded about crimes: it bred crimes. In the same moment that Stalinism emitted ‘humanist’ rhetoric, it occluded the human faculties as part of its necessary mode of respiration. Its very breath stank (and still stinks) of inhumanity, because it has found a way of regarding people as the bearers of structures (kulaks) and history as a process without a subject. It is not an admirable theory, flawed by errors; it is a heresy against reason, which proposed that all knowledge can be summated in a single Theory, of which it is the sole arbitor and guardian. It is not an imperfect ‘science', but an ideology suborning the good name of science in order to deny all independent rights and authenticity to the moral and imaginative faculties. It is not only a compendium of errors, it is a cornucopia out of which new errors ceaselessly flow (‘mistakes’, ‘incorrect lines’). Stalinism is a distinct, ideological mode of thought, a systematic theoretical organisation of ‘error’ for the reproduction of more ‘error.’ (331)

These passages seem to capture the heart of Thompson's conception of socialist humanism: that socialism must ensure that its institutions are designed for real, free human beings -- not for the abstract theoretical assumptions of Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist doctrine. And a genuine commitment to freedom of expression and thought is both a means and an end in this effort: freedom of expression and thought is necessary (as John Stuart Mill too argued) in order to allow the socialist order to progress; and free and equal human beings are the ultimate good of a socialist society.

Certainly Thompson was aware of Stalin's vast crimes by 1956. There was a great deal of information publicly available in the 1930s about the most important crimes of Stalin’s dictatorship, including the Holodomor, the Terror, the show trials, and the Gulag. Malcolm Muggeridge's reporting about the Ukraine devastation was widely available during 1933. And Welsh journalist Gareth Jones traveled through Ukraine and reported the facts of starvation as he observed them firsthand in articles in the Cardiff Western Mail and the London Evening Standard in 1933 as well as a published letter to the Manchester Guardian on May 8, 1933, corroborating Malcolm Muggeridge’s reporting on the famine in that newspaper.

Thompson's independence of mind as a historian is unquestionable, and his willingness to follow his conscience in his relationship to communism was manifest in his actions and writings of 1956 and following years. He rejected the moral authority of the CPGB and the ultimate authority of the party line. But unlike other observers like Orwell, Koestler, or Muggeridge, Thompson seems not to have fully addressed the atrocious crimes of the Stalinist period. He did not squarely confront the atrocities represented by the Holodomor, the Gulag, or the pervasive and repressive use of the security apparatus (NKVD, KGB) to maintain totalitarian control over the citizens of the USSR.

So we are left with a question: why did E.P. Thompson fail to clearly and unequivocally address the Holodomor, the Gulag, and the regime of terror established by Stalin's state?

My Ultimate History Crash CourseAre we in a second Gilded...

My Ultimate History Crash Course

Are we in a second Gilded Age?

Is Trump really a Fascist?

Why are we so politically polarized?

How did corporations take over our politics?

To understand the present, study the past.

Please join me as I share 6 crucial lessons from history.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea – review

Jonathan White‘s In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea examines how changing political conceptions of the future have impacted democracy, arguing that contemporary challenges like economic slowdown and climate change have led to reactive politics and short-termism. Though the book proposes ways to revitalise democracy, Aveek Bhattacharya suggests we may need to seek beyond our political institutions for strategies to build a more open future.

You can read an interview with Jonathan White about the book here. On Monday 11 March at 6.30pm White will speak at an LSE panel event, The politics of the future – find details and register here.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea. Jonathan White. Profile Books. 2024.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea is a book about the history of the future, and what it means for the present. More precisely, it describes how the way people think about the future has evolved over time, and the impact of these changes on democracy. Jonathan White’s central argument is that while optimism for the future once helped build democracy, economic slowdown, climate change, new technology and geopolitical tension mean that “the future no longer seems its [democracy’s] friend”.

In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea is a book about the history of the future, and what it means for the present. More precisely, it describes how the way people think about the future has evolved over time, and the impact of these changes on democracy. Jonathan White’s central argument is that while optimism for the future once helped build democracy, economic slowdown, climate change, new technology and geopolitical tension mean that “the future no longer seems its [democracy’s] friend”.

For democracy to function, White observes, it is critical that people believe an “open future” is possible: that there are alternatives to the status quo, that society can evolve in a range of different ways, and that the people can choose between them. One of the key defining characteristics of democracy – the peaceful handover of power – is premised on changeability of the future: election losers believe that they will get their chance to achieve their vision of society again.

For democracy to function, White observes, it is critical that people believe an ‘open future’ is possible

In the present, White says, it is harder to maintain that patience and faith. The future is regarded with fear and claustrophobia. At various points he describes the future, far from being open, as “closing in”. Catastrophe – societal decay, conflict, environmental collapse – feels hard to avert. Insofar as there are options, they involve deferring to technocrats. There is a “now or never” urgency about politics, and a fear that waiting your turn means leaving it too late because the other side will destroy everything.

Via a tour of historical political thinkers, White sketches the ideas of the future that make for the most vibrant democratic system. Political and social outcomes must seem open, but not in such a destabilising manner as to trigger counter-revolution from those attached to the present. A strand of utopianism can be energising but must be linked to near-term political tactics to be practicable. Efforts to limit uncertainty, to render the future predictable, through calculation and technocracy risk squeezing out the necessary imagination and mass participation of vibrant democracy. At the same time, chaotic impulsiveness and pure disregard for expertise risks descending into fascism. Trying to control the future by keeping it secret is likely to generate conspiracy theories and discontent. Consumerism individualises the future and means we no longer share in it – we move from valorising Victorian steam trains to wanting our own personal cars.

Our perpetual state of emergency, while creating unpredictability, produces reactive politics, designed mainly to return things to the way they were.

The conception of the future we have arrived at today is not, in White’s opinion, sufficiently conducive to democracy. Our perpetual state of emergency, while creating unpredictability, produces reactive politics, designed mainly to return things to the way they were. Short-termism dominates – most notably, through the election cycle, but even longer-term threats like climate change are tractable only by converting them to benchmarks and deadlines. Managerialism and secrecy dominate, empowering organisations like the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund and triggering impulsive populist backlashes.

White’s proposals for rebuilding a more positive conception of the future and revitalising democracy are somewhat surprising. He is sceptical of direct democracy – while more referendums might give ordinary citizens more chance to shape the future, they raise the stakes and perpetuate the “all-or-nothing” politics he thinks is so baleful. Small-scale councils are too small-scale to create significant change, citizens’ assemblies too short-lived to pursue a persistent vision.

White calls for ‘radical representative democracy’, with mass participation in the development of party policy and party members having greater opportunity to recall politicians who fail to deliver on those agreed goals.

Instead, he puts his chips on political parties as the crucibles of a more inclusive, compelling and hopeful vision of the future. He calls for “radical representative democracy”, with mass participation in the development of party policy and party members having greater opportunity to recall politicians who fail to deliver on those agreed goals. It’s an argument with echoes of Peter Mair’s Ruling the Void, which also claimed that the disengagement of ordinary members and politicians from their political parties had led to “the hollowing of Western democracy”.

White’s rebooted party system sounds good in theory, but invites scepticism about its practicality. His central assumption is that citizens’ disempowerment is the root cause of our current democratic malaise, and that the opportunity for greater influence will suffice to tempt enough people to give up their evenings and weekends to political causes. It is not encouraging that the existing parties that have done most to engage with mass movements and improve participation with things like online platforms – Podemos in Spain and the Five Star Movement in Italy – do not seem to have restored democratic confidence in their countries.

The Victorian capitalists who built the factories and railroads may not have been personally attractive, but they inspired progressives and socialists to dream about how their innovations could be used to benefit all.

White is oddly dismissive of the pockets of optimism that do exist outside the political system – most notably Silicon Valley, where ideas like “Effective accelerationism”, the view that technological progress is likely to obviate many of our deepest societal challenges, has taken root. For White, they display the wrong sort of optimism: too consumerist and individualistic, too inclined towards anti-system chaotic thinking, tendencies encapsulated in the figure of Elon Musk, presented as fascistoid, if not fascist. Setting aside whether that is a fair characterisation of Musk, the question it raises is why the confidence of tech companies seems so divorced from the sentiments of wider society. The Victorian capitalists who built the factories and railroads may not have been personally attractive, but they inspired progressives and socialists to dream about how their innovations could be used to benefit all. There are some – figures like Aaron Bastani on the far left and Derek Thompson on the centre left – that are trying to do something similar today, but White does not recognise them as such.

White assumes that the problems of democracy are endogenous: that they are caused by political institutions and must be resolved by them.

Most fundamentally, White assumes that the problems of democracy are endogenous: that they are caused by political institutions and must be resolved by them. But there are more straightforward explanations for the modern morosity. Stagnant economic growth, and the failure of new technologies to demonstrably improve living standards, would naturally be expected to undermine confidence that things will improve. The demographic shift to an older population in rich countries may also have contributed to a lack of vitality and enthusiasm, and a tendency to look back with nostalgia rather than forward with hope. Even among the young, we should not necessarily take perceptions at face value. Phenomena like “climate anxiety” seem to reflect anxiety at least as much as they reflect the climate, and as such will often be psychological, not just political in nature.

That’s not necessarily a comforting thought. Maybe technological abundance is around the corner, maybe the economy will turn around, maybe the mental health crisis will abate – whether by sheer luck or unusually effective action – and people will start to feel better about the future. But In the Long Run suggests that fixing democracy’s problems, renewing our faith in the open future, is a much bigger task than tweaking its institutions.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Ryan Rodrick Beiler on Shutterstock

The Upside Down: History Is More than Its Set Pieces

The house I live in is called Crimea House. It was once the home of the foreman of Crimea Yard, a flash 19th Century sawmill with a steam-driven beam engine and a 50-foot-high ornate brick chimney. Stories persist that the sawmill made planks for ships that fought in the Crimean War, but it seems unlikely: we’re a long way from the nearest port.

The owner of the Great Tew estate in the 1850s – a rather remarkable classicist and amateur inventor called Matthew Piers Watt Boulton – had recently retired and was busy modernising the big house and its outbuildings. The date for that work is 1856, the year the Crimean War ended. Like many other streets, pubs and public buildings across England, our sawmill was almost certainly named to mark Britain’s recent victory. Plus, the architects Boulton had employed were gothic revival specialists, which would explain the rather grandiose decoration of the chimney.

If asked about the Crimean War, most of us can probably recall the Lady with the Lamp and the Charge of the Light Brigade. As for who was fighting whom, and for what, the answers are much less clear.

Living in a house that carries its name has inspired me to look a little deeper. And the conflict turns out to resonate with contemporary relevance.

It began in Palestine, then as now, a place of contested religious priorities.

In theory, the minor disagreement between Russia and the Ottoman Sultan over access to Christian sites in Jerusalem could have been swiftly resolved by diplomatic activity by Britain and France. As so often, it was a war that no one really wanted but, as ever, each nation felt there was something to gain.

Russia wanted to flex its military muscles and prove it deserved a seat around the European table. Napoleon III of France was looking to consolidate his position as Emperor (he’d crowned himself the year before). Britain, always with its eye on the economic main chance, had recently tripled its trade with Turkey and needed to protect the passage to India.

In July 1853, Tsar Nicholas I invaded Moldavia and Wallachia (now part of Romania but then under Turkish rule). Turkey, in turn, declared war on Russia. In November, the brutal Russian destruction of the Ottoman fleet at Sinope on Turkey’s northern coast left 3,000 dead. Portrayed as a massacre by the Western press, this hardened popular anti-Russian sentiment and led to declarations of war by Britain and France the following March.

What followed was two-and-a-half years of bloody and attrition warfare, remembered for costly strategic blunders on both sides. Some 650,000 lives were lost, more than three-quarters of these due to the depredations of secondary infection and cholera – something that, despite Florence Nightingale’s best efforts, was only fully understood after the war.

It was the first war in which railways and telegraphs were used to supply the frontlines and the first with ‘embedded’ war reporters such as William Henry Russell and the young Leo Tolstoy. For the first time, photographers like Roger Fenton were able to capture vivid images of real soldiers and actual battlefields.

Making the public feel closer to a war changed their view of it. It created the cult of the brave British soldier which was in marked contrast to those of the Napoleonic campaigns who were generally disparaged as undisciplined, venal mercenaries. This heroic status was given extra impetus by the introduction of the Victoria Cross in 1856, which soon became the ultimate symbol of British military valour.

The scrutiny of reporters on the ground also meant the hasty and incompetent decisions of the senior officers were mercilessly exposed, seeding the ground for the myth of ‘lions led by donkeys’ in the Great War and even, as Fintan O’Toole has persuasively argued, the peculiarly British cult of the ‘heroic failure’ that resurfaced most recently among Brexiters.

Then, as now, the brutality of the war led to street protests. In January 1855, a ‘snowball riot’ in London’s Trafalgar Square saw a large crowd pelt cabs and pedestrians with snowballs and had to be put down by truncheon-wielding police. A parliamentary request for the Government to produce accurate casualty figures led to the resignation of Lord Aberdeen’s administration. In Russia, the humiliation of defeat enabled the new Tsar Alexander II to modernise his institutions and abolish serfdom, as a much less costly way of restoring Russia’s status as a great power.

So, the Crimean War still has much to teach us, not least that history is always more than its obvious set pieces. For example, the chimney in Crimea Yard isn’t a chimney at all. It’s a purely decorative folly: the steam escaped from a much smaller vent on the side of the building.

So it goes with history. Truth escapes from the side vents.

Suffrage and the Arts: Visual Culture, Politics and Enterprise. Miranda Garrett and Zoë Thomas (eds.). Bloomsbury. 2019.

Suffrage and the Arts: Visual Culture, Politics and Enterprise. Miranda Garrett and Zoë Thomas (eds.). Bloomsbury. 2019. Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists. Elizabeth Crawford. Francis Boutle Publishers. 2018.

Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists. Elizabeth Crawford. Francis Boutle Publishers. 2018. As Good as a Marriage: The Anne Lister Diaries, 1836-38. Jill Liddington. Manchester University Press. 2023.

As Good as a Marriage: The Anne Lister Diaries, 1836-38. Jill Liddington. Manchester University Press. 2023. The Other Emmeline: The Story of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Jane Grant. Francis Boutle Publishers. 2023.

The Other Emmeline: The Story of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Jane Grant. Francis Boutle Publishers. 2023. Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars. Francesca Wade. Faber & Faber. 2020.

Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars. Francesca Wade. Faber & Faber. 2020.  The Hindu Bard: The Poetry of Dorothy “Dorf” Bonarjee. Dorothy Bonarjee (author) Mohini Gupta and Andrew Whitehead (eds.). Honno. 2023.

The Hindu Bard: The Poetry of Dorothy “Dorf” Bonarjee. Dorothy Bonarjee (author) Mohini Gupta and Andrew Whitehead (eds.). Honno. 2023.