community

Mobilising opposition to AUKUS – The Marrickville Declaration

Community opposition to the AUKUS project finds expression in a Sydney suburb. Back in March 2023, a public meeting was held in the Town Hall of the Sydney suburb of Marrickville, under the title “Can War be Avoided or Will Our Peace be Shattered?”. That meeting took place just a few days after the AUKUS Continue reading »

Star Trek: Discovery, Doctor Who, Chucky & More: BCTV Daily Dispatch

In today's BCTV Daily Dispatch: Community, OMITB, The Rookie, TWD: The Ones Who Live, Chucky, Star Trek: Discovery, Doctor Who, and more!

Chinese Australians are happy ScoMo’s leaving politics. Is this an opportunity for the Liberals?

This level of dislike for Morrison among Chinese Australians should come as no surprise, given that the roughest patch in Australia-China relations happened during his reign. But now he’s gone, can Peter Dutton begin to mend fences? Following the announcement of Scott Morrison’s decision to quit politics, Sydney Today, Australia’s most popular Chinese-language digital media outlet, conducted Continue reading »

Welcome the year of the Dragon!

The Year of the Dragon is bound to be big. Among the twelve zodiac animals that mark the traditional cycle of calendar years, the dragon is the only mythical beast and the most powerful. It stands in marked contrast to the rabbit that will hand over its psychic reign on 10 February. Soothsayers may well Continue reading »

An Ancestral River Runs Through It

Jeff Wivholm isn’t partial to mountains. He likes to be able to see the weather rolling in, something remarkably possible in the northeastern corner of Montana.

On a cold January morning, Wivholm drives the dirt roads between farms in Sheridan County, where he’s lived for all his 63 years, with practiced ease, pointing out different plots of land by who owns them. And if he doesn’t know the family name, Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District or Brooke Johns with the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge — both sitting in the backseat of his truck — can supply it.

If you look to the right there, Wivholm says, you can see the valley created by the aquifer. Maybe he can, his eyes accustomed to seeing dips and crevasses in, to an unfamiliar eye, a starkly flat landscape. He laughs and says it takes some getting used to.

That aquifer isn’t unique in Montana. There are 12 principal aquifers running like underground rivers throughout the state. But the way Sheridan County uses the water is.

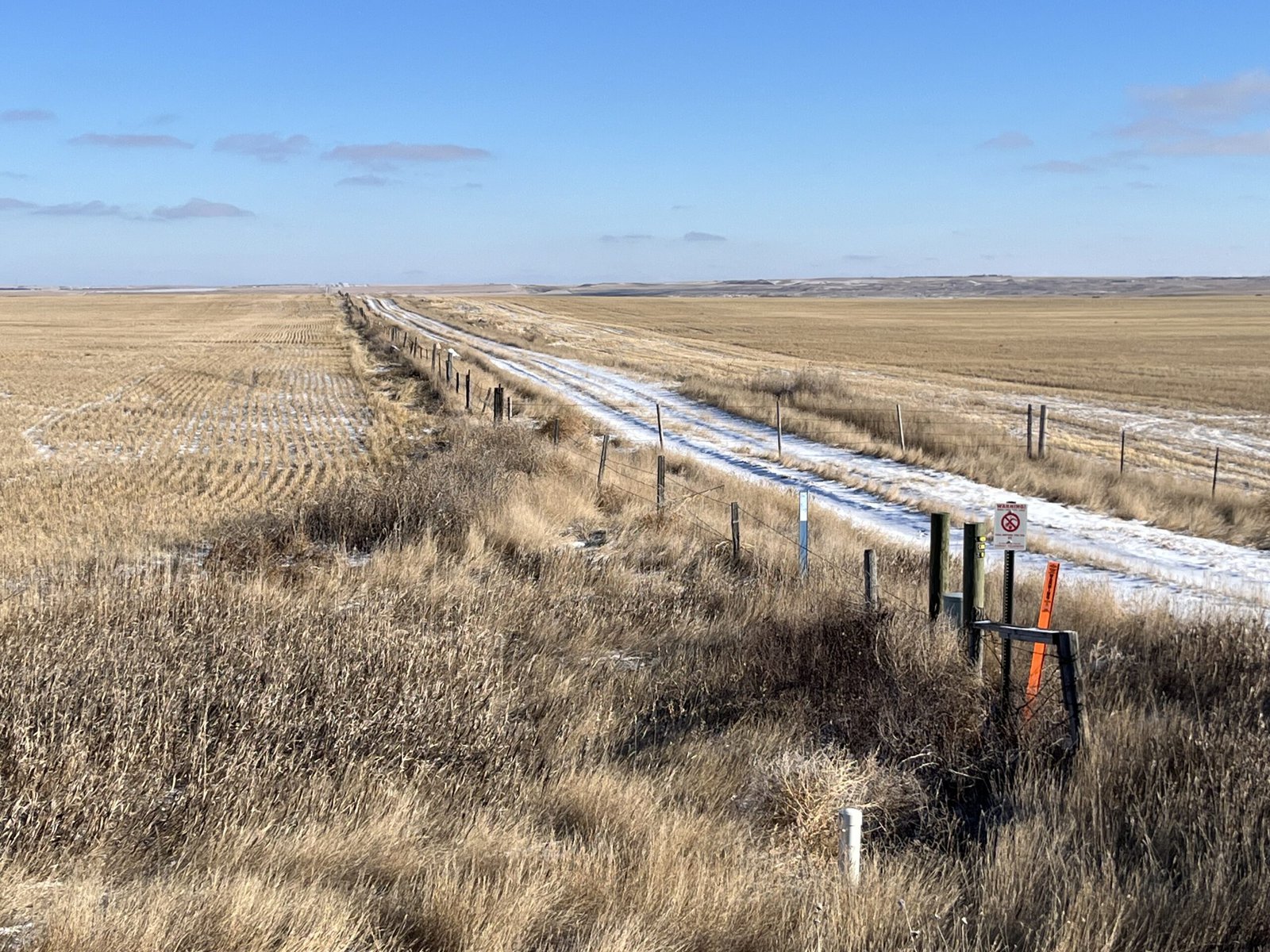

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

The Big Muddy Creek flows through dams and diversions, pictured on the right, that are managed by the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge to fill the lake as needed. Credit: Keely Larson

Montana is in relatively good shape as far as its groundwater supply goes, something uncommon across much of the country, geologist John LaFave with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology says. State politicians initiated a groundwater study over 30 years ago after years of intense drought and fires and a lack of data.

But Sheridan County was ahead of the game: The county’s conservation district started studying its groundwater in 1978, before state monitoring began.

In 1996, the district was granted a water reservation, or water allocated for future uses, from the state, which meant it could take a certain share of water from the Clear Lake Aquifer. Because of all the data it gathered through studying its groundwater, the district developed a unique way of using and distributing that water.

What’s unusual is how intentional the collaboration was and how extensive the groundwater monitoring was and continues to be. The district does this by working with farmers, tribes and the US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) to ensure water can be used by those who need it — those who would be most affected by any degradation to the water — without negatively impacting the environment.

And it’s worked. The conservation district has been using its geologically special aquifer — a gift granted to this area by the last Ice Age — to irrigate crops, provide jobs for the region and keep agriculture dollars within the community for almost 30 years while fielding few complaints.

“To me, this represents the way groundwater development should occur,” LaFave says.

Sheridan County is extremely rural, home to about 3,500 people across its 1,706 square miles. Agriculture is a big economic driver. Bird hunting is an attraction for locals and visitors. The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located in both Sheridan and Roosevelt Counties and managed by the USFWS, is home to many migratory bird species. It’s the largest pelican breeding ground in Montana and the third-largest in the country.

This early January morning, it’s about five degrees, but there isn’t a lot of snow on the ground. Over coffee and breakfast in Plentywood — the county seat — Yoder and Wivholm say this winter has been warmer and drier than usual.

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

From left to right, Jeff Wivholm, Marlowe Onstead and Amy Yoder look through maps of irrigation pivots and aquifer allocations inside the Sheridan County Conservation District office in Plentywood. Credit: Keely Larson

Dry weather is not uncommon here. Droughts in the 1930s and ’80s were particularly rough. Also in the ’80s, irrigation technology was becoming more common and efficient, Wivholm says, and people began to pay more attention to the possibility of an aquifer as a way to ensure water would be available for irrigation.

“There are several nicknames for much of this property, but it was basically ‘poverty flats,’” Jon Reiten, hydrogeologist with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, says. The soil is sandy, gravelly and drought-prone. Not great for dry-land farming.

Marlowe Onstead was the first farmer in Sheridan County to use the aquifer for his pivot irrigation in 1976.

“Couldn’t raise the crop on it before,” Onstead says. After irrigation, he was able to grow alfalfa.

According to Reiten, the aquifer ranges from a mile to six miles wide and two to three hundred feet deep. The ancestral Missouri River channel, discovered in Sheridan County in 1983 as monitoring began, flowed north into Canada and east into Hudson Bay. That channel was dammed by glaciers in the last Ice Age and left behind a reservoir that was buried as glaciers melted, creating the Clear Lake Aquifer. Since the materials left behind were coarse and varied, water could move easily and be stored in great depths. A downside is that these glacial aquifers can take a long time to refill.

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

The vertical white cylinder is one of many that Amy Yoder with the Sheridan County Conservation District checks throughout the growing season. She opens up the top, connects the data logger inside to a laptop and collects information on the aquifer water level and how much water has been used for irrigation. Credit: Keely Larson

As drought dragged on in the ’80s, locals and county and state authorities set about figuring out the best way to distribute the aquifer’s water. Medicine Lake lies on top of some of the aquifer, and the Big Muddy Creek — where the Fort Peck Tribes require a minimum in-stream flow to promote ecosystem health — is at its southwestern border.

The Fort Peck Tribes and the USFWS were concerned about their respective water levels and how they’d be impacted by irrigation. Reiten says the USFWS was objecting to just about every water rights case that went to the state at the time, and all that litigation ended up in water court.

“That’s a lot to put on a producer, to have to go up against the federal government,” Reiten says.

Negotiations with the USFWS and the Fort Peck Tribes led to the formation of an advisory committee and the transfer of the water reservation on the aquifer from the state to the conservation district. (Per Montana water law, all water belongs to the state and individuals are required to get a water right to use it in a particular way — in this case, for irrigation.) Since then, Sheridan County Conservation District has had the authority to give water allocations from the Clear Lake Aquifer to producers without the producers having to appeal to the state.

The maximum amount of water that can be pulled from the aquifer is just over 15,000 acre feet total, a number set by the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Currently, the district is using about 10,000 acre feet. Increases are allowed as long as monitoring shows the aquifer isn’t being overly impacted by irrigation.

Credit: Keely Larson

The Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge is home to the third largest pelican breeding ground in the country and the largest in Montana. Negotiations with the US Fish & Wildlife Service, which manages the refuge, helped Sheridan County Conservation District obtain the water reservation for the Clear Lake Aquifer.

“We were basically forced to monitor it, but it only makes good sense,” Wivholm, who has been on the conservation district board since 1994, explains. The district wouldn’t want to grant someone a right only to find out in five years that there’s not enough water.

Once a year, the committee meets to assess new water rights. The committee includes the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, the state Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, representatives from the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, county commissioners, a county planner, the Fort Peck Tribes and a representative with the United States Geological Survey.

If a farmer wants an irrigation pivot, they have to “pump it hard for 72 hours,” Wivholm says, to make sure there is enough water for their request, and understand how that pumping affects other wells nearby.

Data comes from Yoder’s efforts. She collects readings from data loggers placed in the ground throughout the county from April through October. For the first and last collections, she visits 201 wells and it takes her three 12-hour days to get to them all. Driving around in Wivholm’s truck, she points out some of her data loggers sticking up from the ground every few minutes.

Through monitoring, Sheridan County Conservation District and the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology have been able to map the entire aquifer. They take note of the water levels, monitor each irrigation pivot and can see seasonal fluctuations.

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

Rodney Smith’s pivot is the largest connected to the aquifer. The structure in the foreground remains stationary, while the rest on wheels moves around — pivots around — the fixed structure. Credit: Keely Larson

“It’s kind of a hidden resource, but the amount of crops that we can get off of the poor ground that is above the aquifer is amazing,” Yoder says. She lists corn, wheat, chickpeas, lentils, canola, mustard and alfalfa.

Another farmer in the area, Rodney Smith, has been irrigating from the Clear Lake Aquifer for over 35 years and has the biggest pivot connected to the aquifer.

Smith says irrigating has been economically beneficial: His farm isn’t as dependent on the weather, and it’s taken the risk out of production. Smith Farms Incorporated produces hay for livestock and sells it to other ranchers in the area. Smith also leases land out to other farmers who grow potatoes and sugar beets.

From an aerial view, his circular pivot plots show different colors of green and brown, indicating a variety of crops grown.

Smith had an early contested pivot case with the state of Montana, before the water reservation was transferred to the conservation district, which went to the state water court.

The gist of the case was that Smith Farms wanted to change their method of irrigation and the USFWS was concerned it might impact the Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Data and monitoring done by the conservation district backed up Smith’s case.

“When you start irrigating, you wonder what is the capacity, or how much can you irrigate,” Smith says. “It’s always interesting to know what it’s doing.”

Credit: Google Earth

Land that is irrigated with pivot irrigation shows up in circular plots from above due to the way the structure pivots around a fixed point. Here, the circular pivot plot is sliced into different colors where different crops or phases of harvest have occurred.

Johns, with the wildlife refuge, says the refuge has a water reservation on Medicine Lake and is allowed to keep the lake filled for the protection of migratory birds. The refuge operates dams and diversions to maintain this need. Making sure any irrigation wouldn’t draw down the level of the lake has been a goal from the beginning, Johns says, and so far, that hasn’t been an issue.

There haven’t been any other contested cases on aquifer irrigation, and many, including Smith, see this as a success in having local control over a local resource.

“Water rights are such a contentious thing,” Johns notes. “And without the data, had they not started this years ago, it would be hard to start it today and get the same momentum they did.”

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Arnold Bighorn, water rights administrator for the Fort Peck Tribes, says the collaboration between all those affected by the aquifer — counties, tribes and the wildlife refuge — has worked well.

“Everybody’s on the same page, which is good,” Bighorn says.

Monitoring groundwater like this is unique in Montana, according to Reiten, particularly for irrigation development. But there are successful examples in other states.

Before he came to Montana, Reiten worked for the North Dakota State Water Commission, where the same type of monitoring was going on that he helped start in Plentywood. He is working on another aquifer in Sidney, Montana, about 85 miles south of Plentywood, to develop a similar system.

“We’re applying the same methods there to try to develop that aquifer without affecting anything else,” Reiten says.

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Wivholm, who has lived in Medicine Lake, Montana for all his 63 years of life, drove along dirt roads earlier in the day with ease, knowing the pheasants and grouse would flap out of the way as his truck sped along. Credit: Keely Larson

Many conservation districts across Montana have water reservations on surface water, Yoder says, but Sheridan County Conservation District is one of only two districts that manages a groundwater reservation.

“I haven’t heard of any other places that have quite the extensive monitoring that we have and the time range that we have,” Yoder says.

There continues to be room for more water and improvement in how it’s used.

Wilvhom would like to see soil monitoring, so producers can know when to water and when they’re using too much. Devices are available that farmers could bury in the ground to monitor soil moisture and temperature.

Managing the aquifer has been “a collaboration to help the whole community do good,” Wivholm reflects later in the week, when Plentywood has reached -58 degrees with a windchill. “It helps the whole health of the whole ecosystem.”

The post An Ancestral River Runs Through It appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Building More Than Trails

There is some debate as to where the name “The Lost Sierra” comes from, but it’s become the common name — and an apt one — for the lesser-traveled towns, alpine lakes and peaks near Reno, Nevada, and within the northern reaches of eastern California’s Sierra mountains.

More than a dozen communities are tucked away across this area, which is fragmented by the mountainous terrain of the surrounding national forests and, more recently, by extreme wildfire.

Over the past few years, Trinity Stirling, who lives in Quincy and grew up in the Lost Sierra, has made it her mission to help connect these scattered communities with the hopes of giving their economies a boost by creating more recreation opportunities. And that mission starts with trails.

The Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship Trail Crew building a solid trail foundation in steep terrain. Credit: Ken Etzel

The Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship Trail Crew building a solid trail foundation in steep terrain. Credit: Ken Etzel

As the former project manager with the Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship, Stirling worked on a long-term project to connect more than a dozen rural towns with a long-distance trail stretching about 600 miles. Stitched across federal public land, the trail network is coming together in stages, building off existing trails. So far, about 74 miles are under construction and 30 miles have been finished — with broad support for building more. “A lot’s happening,” says Greg Williams, the group’s executive director. For now, he says the biggest challenge is funding.

The goal of the Lost Sierra Route, as the long-distance trail will be known, is to improve access to public land at a time when more and more people want to get outside, while at the same time connecting isolated communities and working to diversify the regional economy, which grew around the booms and busts of natural resource industries like mining, logging and ranching.

“Obviously we’re connected by roads,” Stirling says. “We have a lot of dirt roads. But one of the early concepts for this project, once it’s built, is creating a community passport.” The passport would encourage trail users to travel from town to town, checking out different businesses and getting a sense of the varied places connected to the trail system.

Historic buildings of downtown Quincy in the fall. Credit: Patrick Cavender

Historic buildings of downtown Quincy in the fall. Credit: Patrick Cavender

Already, the region is seeing success in building out a stable recreation economy. It’s a popular spot for mountain bikers, who are drawn to existing trails and races like the annual Downieville Classic, which Williams created in 1995. Williams, who started the stewardship group in 2003, says as he worked on more trail projects, there was increasing interest in a regional system.

“We’d go to Board of Supervisor meetings or Chamber of Commerce meetings and neighboring towns would say, ‘Hey, what about us? We’re struggling. We’re surrounded by national forests. We live in a beautiful place that we feel like people want to come [visit],’” Williams recalls.

Williams points to Quincy, a town of about 1,600 people surrounded by national forest land, as a strong indicator for the potential in creating more recreation opportunities. “Quincy just had a brewery-restaurant open. So now there are two brewery-restaurants in town that didn’t exist before trails were there,” he says. “The local motels are buying new mattresses and painting the sidings…. So we’re seeing it happen.”

Credit: Patrick Cavender

Many mountain bikers stop to eat a well-earned meal at Taylorsville Young's Market. The following day, the Lost Sierra Route will take them to Quincy.

The businesses Williams talks to say they “need more people,” especially midweek.

And more trails, connected and organized, are likely to bring more people. “Nationwide, the outdoor industry just grew to a $1.1 trillion annual industry, which is ginormous,” Stirling says.

The data bears this out.

For decades, rural communities across the country, from New Mexico to Vermont, have looked to recreation as a way to diversify their economies, create resilience and improve quality of life.

This is especially true in areas that grew with extractive industries — oil and gas, mining, grazing and timber — where boom, busts and drought left economies vulnerable, according to Megan Lawson of Headwater Economics, a Montana-based firm that researches outdoor recreation.

The view of Crystal Lake and Taylorsville in Indian Valley from the top of Mt. Hough. Credit: Patrick Cavender

The view of Crystal Lake and Taylorsville in Indian Valley from the top of Mt. Hough. Credit: Patrick Cavender

Trails can serve multiple purposes for communities, Lawson says, and the economic impact is not only about attracting tourists. Having opportunities to explore trails, fly fish in scenic rivers or take a peaceful walk after work can make places more attractive to live or start a business in.

Lawson says this has been especially true in rural areas, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated the growth of the outdoor recreation industry. In 2019, Headwater Economics published a report finding that more people moved into rural recreation counties — on average — between 2010 and 2016 than non-recreation rural counties, where populations fell.

She says rural counties that invested in the infrastructure to support recreation opportunities were more resilient in the face of boom-and-bust cycles and other economic challenges.

Trails are one of the things that brought Jonas Crews, an avid biker, to northwest Arkansas. Crews studies outdoor recreation as an economist for Heartland Forward, a research group that looks at public policy in 20 states (the group, based in Bentonville, Arkansas, was started with funding from the heirs of Walmart, which is headquartered there). Bentonville is the municipal anchor for hundreds of miles of trails, some of which connect to outlying rural areas through gravel paths.

Spring is one of the busiest times. In any given week, Crews says all you have to do is ask people where they are from and you will find out which state is on spring break based on who is using the regional mountain bike trails.

As more people went outdoors and remote work became an option for high-wage service jobs during the pandemic, some workers moved from urban counties to counties with better access to outdoor recreation, a trend not only in hotspots like the Mountain West but across the country.

Credit: Patrick Cavender

The communities along the Lost Sierra Route are in good company: Rural communities from New Mexico to Vermont have looked to recreation as a way to diversify their economies, create resilience and improve quality of life.

In response, Chris Perkins, a vice president with the Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, says that he is “seeing communities of all sizes [that] have all sorts of political backgrounds and demographics around the country invest in outdoor recreation, infrastructure and access like never before.” Yet as more recreation has attracted new residents, cost of living has soared in many towns.

“Tourism is incredible but it doesn’t pay a whole lot, frankly,” Crews notes. He argues that regions have seen success in attracting higher-paying jobs when they diversify beyond tourism, lure outdoor businesses and develop expertise in a specific part of the industry.

Not relying solely on tourism, he says, is vital because “we don’t want to see every town become a ski town where the people that grew up there can’t live there anymore because they can’t afford it.”

Sierra Buttes Trail Crew member Mandy Beaty refining trail. Credit: Ken Etzel

Sierra Buttes Trail Crew member Mandy Beaty refining trail. Credit: Ken Etzel

Earlier this year, Outdoor Recreation Roundtable released a second version of its rural economic development toolkit. Notably, it included a section devoted to addressing housing issues, what Perkins describes as “the challenge.” But there are other barriers too: Funding for infrastructure, getting community buy-in, varied land ownership and the time it takes to plan new trails.

Working with different parts of communities early on is critical, says Claire Polfus, the recreation programs manager for the state of Vermont. Even successful recreation projects bring change, and “there’s people who win and people who lose out of any change that happens,” she says.

For example, Kingdom Trails, a network of trails spanning more than 100 miles based in East Burke, Vermont, has achieved its goals and more, Polfus says. But it has also hit roadblocks ranging from issues over land ownership to the rising cost of living in the areas surrounding the trails.

She says it’s important to engage first with communities and ask, “What do we want to be?”

In some cases, what a community wants and needs can shift due to circumstances beyond its control.

In 2020 and 2021, the North Complex Fire, the Dixie Fire and the Beckwourth Complex burned through more than one million acres in the Lost Sierra, devastating forests and many of the rural towns at the center of the Lost Sierra Route. The mountains that tower over the region drain into the upper Feather River watershed, which has seen more than half its acreage burn since 2017. The Dixie Fire in 2021 left downtown Greenville decimated, reducing historic buildings to rubble.

Even before the fires, Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship worked to solicit feedback and build wide support from a wide range of local politicians, government agencies and business organizations.

Community input has been a key part of Sierra Buttes Trails Stewardship’s efforts. Courtesy of Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship

Community input has been a key part of Sierra Buttes Trails Stewardship’s efforts. Courtesy of Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship

Stirling says people are mostly “in alignment” with the idea of building additional trails.

But, she acknowledges, “our region’s catastrophic wildfires reprioritized everyone’s community needs and everyone’s personal interest. We’re still walking this path for connected communities, but also recognizing that yes, trails are not at the top of everyone’s Christmas wish list.”

“Homes and rebuilding communities are there as well,” she adds.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

Trails can take years to build out, and the Connected Communities project is years from its full completion. That has provided opportunities to rethink the trails in response to feedback — and fires. Williams, the executive director, says fire “changed the look and feel of the landscape, but also how we look at trails.” The organization plans to look at managing vegetation in the 100-foot corridor around trails to help prevent the spread of future fires. New trails, he says, can also play a role in rebuilding Greenville, a town that was just hanging on, even before the fires.

“Recreation is key to their future,” he says of the Lost Sierra Communities. “A lot of the people who live there live there because of the access to public lands, whether they walk, ride a horse, ride a motorcycle or hop in a jeep and go. That’s super important to their lifestyle and well-being. So this project fits right in line.”

The post Building More Than Trails appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Wattle Day: A natural choice for Australia Day’s ideals of diversity and resilience

In 2018, I wrote about Australia Day and Wattle Day for The New Daily. While in 2024 some crazy drums still beat to PC tunes, the federal government has lowered the temperature. Soon we will be able to have a rational debate which may lead us to September 1, Wattle Day, which could become the Continue reading »

Australia Day 2024 poses more than the usual challenges

January 26 poses more than the usual challenges in 2024. Barely 100 days since the failed referendum there is the real prospect of the respective advocates and supporters reigniting a process, the only real outcome of which was community division. There is the risk of stirring more pain for some and a sense of triumphalism Continue reading »

Australia Day: The differences that unify

Australians are a perverse bunch. We tend to exhibit two distinct and contradictory sentiments every Australia Day. For many, it is an excuse to bask in overweening pride and to declare loudly our “normalcy” as citizens of this great land. It presents an opportunity for flag-wavers, anthem-singers, chauvinists and proud nationalists, to strut their stuff. Continue reading »

Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage – review

In Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage, Michael Herzfeld considers how marginalised groups use nationalist discourses of tradition to challenge state authority. Drawing on ethnography in Greece and Thailand, Olivia Porter finds that Herzfeld’s concept of subversive archaism provides a useful framework for understanding state-resistant thought and activity in other contexts. A longer version of this post was originally published on the LSE Southeast Asia Blog.

Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage. Michael Herzfeld. Duke University Press. 2022.

“The nation-state depends on obviousness because, in reality, its own primacy is not an obvious or logical necessity at all. It is presented as a given, and most people accept it as such. Implicitly or explicitly, subversive archaists question it” (123).

“The nation-state depends on obviousness because, in reality, its own primacy is not an obvious or logical necessity at all. It is presented as a given, and most people accept it as such. Implicitly or explicitly, subversive archaists question it” (123).

The excerpt above encapsulates the central thesis of the social anthropologist and heritage studies scholar Michael Herzfeld’s Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage. That being said, that the modern nation-state is widely accepted as the primary unit of territorial and cultural organisation, but that there are a group of people, subversive archaists, who question this rhetoric. Subversive archaism challenges the notion that the nation-state, constrained by bureaucratic organisation and with an emphasis on an ethnonational state, is the only acceptable form of polity. Subversive archaists offer an alternative polity, one legitimised by understandings of heritage that date back further than the homogenous ‘collective heritage’ proposed in state-generated discourses for the purpose of creating a ubiquitous representation of national unity (2). As Herzfeld suggests, subversive archaists instead reach into the past to reclaim older and often more inclusive polities and understandings of belonging, and in doing so, they utilise ancient heritage to challenge the authority, and very notion, of the modern nation-state.

Subversive archaists instead reach into the past to reclaim older and often more inclusive polities and understandings of belonging

Herzfeld examines the concept of subversive archaism through comparative ethnography, drawing on long-term ethnographic fieldwork with two communities: the Zoniani of Zoniana in Crete, Greece, and the Chao Pom of Pom Mahakan, Bangkok, Thailand. At first, the two communities appear geographically and culturally distinctively dissimilar. However, they share one important feature neither country has ever been officially colonised by a Western state. Herzfeld ascribes the term “crypto-colonialism”, a ‘disguised’ form of colonialism, to both Greece and Thailand, as states that despite never being officially colonised, were both under constant pressure to conform to Western cultural, political, and economic demands. Herzfeld explains that such countries place a great emphasis on their political independence and cultural integrity having never been colonised, yet many forms of their independence were dictated by Western powers.

In identifying themselves with the heroic past of the nation state, [subversive archaists] legitimise their own status as rightful members of the nations in which they now find themselves marginalised.

In Chapter Two, Herzfeld explores the historical origins of the images and symbols mimicked by subversive archaists to challenge the dominant, often ethnonationalist, narrative of the nation-state. Subversive archaists ransack official historiography and claim nationalist heroes as their own, and in identifying themselves with the heroic past of the nation state, they legitimise their own status as rightful members of the nations in which they now find themselves marginalised. Rather than reject official narratives, subversive archaists appropriate them, in ways that undermine state bureaucracy. For example, the Zoniani (and many Cretans) do not reject the official historiography of the state, which emphasises continuity with Hellenic culture. In fact, they fiercely defend it, and go one further, by citing etymological similarities between Cretan dialects that bear traces of an early regional version of Classical Greek. In doing so, they make claims that they have a better understanding of history than the state bureaucrats.

Chapter Three explores belonging and remoteness through kinship structures and geographical location. Herzfeld highlights how the nation-state uses the symbolic distancing of communities as remote or inaccessible as a tool to marginalize communities. Pom Mahakan is located on the outskirts of Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, and nowadays Zoniana is accessible by road. Herzfeld argues that the characterisation of these communities as remote and inaccessible is applied by hostile bureaucracies rather than by the communities themselves as an extreme form of intentional political marginalisation.

Zoniani society is still structured by a patrilineal clan system, and Chao Pom society by a mandala-based moeang system. These structures represent an older, and alternative, system of polity to the modern bureaucratic nation-state.

In Chapter Four, Herzfeld proposes that we reframe the assumption that religion shapes cities and instead think about how cosmology shapes polities. In particular, how Zoniani society is still structured by a patrilineal clan system, and Chao Pom society by a mandala-based moeang system. These structures represent an older, and alternative, system of polity to the modern bureaucratic nation-state. For example, the Chao Pom embrace religious and ethnic minorities, arguing that diversity is representative of true Thai society, and that tolerance and generosity are true Thai ideals. The notion of polity itself is the focus of Chapter Five which explores how Pom Mahakan and Zoniana have cosmologically distinct identities that, when conceptualised as part of the same system as the nation-state, both mimic and challenge the state’s legitimacy, thus inviting official violence.

Herzfeld argues that what sets subversive archaists apart from the “state-shunning groups” described by Scott […] is their ‘demand for reciprocal respect and their capacity to play subversive games with the state’s own rhetoric and symbolism’

Herzfeld explains how neither the Zoniani nor Chao Pom fit into the James C. Scott’s concept of “the art of not being governed,” applied to Zomian anarchists who flee from state centres into remote mountainous regions in northeastern India; the central highlands of Vietnam; the Shan Hills in northern Myanmar; and the mountains of Southwest China. Herzfeld argues that what sets subversive archaists apart from the “state-shunning groups” described by Scott, but also makes them representative of a widespread form of resistance to state hegemony, is their “demand for reciprocal respect and their capacity to play subversive games with the state’s own rhetoric and symbolism”. Arguably, the reason that the Zoniani and Chao Pom can demand ‘reciprocal respect’ is related to their ethnic, historical, and cultural affiliation with the majority that marginalises them. The ethnic minorities of Zomia do not benefit from the same types of affiliation.

Ultimately, Herzfeld’s model of subversive archaism offers us an example of understanding how marginalised groups challenge and subvert authority

Ultimately, Herzfeld’s model of subversive archaism offers us an example of understanding how marginalised groups challenge and subvert authority. Herzfeld is not proposing that any given group needs to fit neatly into the category of subversive archaists, but rather how some groups reach back into the past to offer an alternative future. In Chapter Eight, Herzfeld explores the future of subversive archaist communities, and also how subversive archaism might mutate into nationalist, and potentially dangerous, movements. The Chao Pom embrace ethnic and religious minorities on the grounds that acceptance and inclusion are true Thai ideals. However, there are dangers to invoking ideologies attached to ‘true’ ideologies of national cultures and traditions, and other types of communities can utilise the rhetoric of subversive archaism. For example, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, “antimaskers” use the language of “liberty” and “democracy” against the modern bureaucratic state, seeking to transform the present into an idealised national past.

I was initially sceptical about who qualified as a subversive archaist. At first, the term seemed too rigid, a community had to be marginalised by the state authority, but associate themselves with the majority and use the language of the state to legitimise themselves their alternative polity. Then, the term seemed too broad, it is not specific to a certain geography, ethnic identity, or religion, and can apply to religious and non- religious groups. Subversive archaism might help us make sense of the Chao Pom and the Zoniani, but who are the subversive archaists of the contemporary world? Then, one morning, when listening to a podcast from the BBC World Service covering the inauguration of India’s controversial new parliament building, I heard a line of argument, from the Indian historian Pushpesh Pant, that struck me as being rooted in subversive archaism.

When asked about the aesthetics of the new parliament building, Pant remarked “I think it is a monstrosity… If the whole idea was to demolish whatever the British, the colonial masters, had built, and have a symbolic resurrection of Indian architecture, I would even go, stick my leg out and say Hindu architecture, it should have been an impressive tribute to generations of Indian architectural tradition Vastu Shastra. Vastu Shastra is the Indian science of building, architecture.” He goes on to say: “How does this symbolise India?”

I suspect that given the rise of nationalist movements across the globe, the tools of subversive archaism, rather than subversive archaists groups per se, will become all the more visible.

In invoking the Vastu Shastra, the ancient Sanskrit manuals of Indian architecture, and the Sri Yantra, the mystical diagram used in the Shri Vidya school of Hinduism, Pant demonstrates his deep understanding of ancient Indian architecture and imagery. And in doing so, he highlights the missed opportunities of the bureaucratic state in designing their new parliament building to create a building that was truly representative of archaic Indian architecture. He does what Herzfeld describes as “playing the official arbiters of cultural excellence [here, the BJP] at their own game”. I suspect that given the rise of nationalist movements across the globe, the tools of subversive archaism, rather than subversive archaists groups per se, will become all the more visible.

This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books blog as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia. This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the LSE Southeast Asia Blog, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image Credit: daphnusia images on Shutterstock.