book reviews

Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update

The weekly report on new and revised entries at online philosophy resources and new reviews of philosophy books…

New:

- Lambert of Auxerre by Sara L. Uckelman.

- Aristotelianism in the Renaissance by David Lines.

Revised:

- Feminist Philosophy of Biology by Carla Fehr and Letitia Meynell.

- Adolf Reinach by Alessandro Salice, James DuBois, and Barry Smith.

- Early Philosophical Interpretations of General Relativity by Thomas A. Ryckman.

- Heidegger’s Aesthetics by Iain Thomson.

- Hegel’s Aesthetics by Stephen Houlgate.

- The Neuroscience of Consciousness by Wayne Wu and Jorge Morales.

- 19th and 20th Century Chilean Philosophy by Ivan Jaksic.

- Counterfactual Theories of Causation by Peter Menzies and Helen Beebee

IEP ∅

NDPR ∅

- The Rules of Rescue: Cost, Distance, and Effective Altruism by Theron Pummer is reviewed by Violetta Igneski.

Open-Access Book Reviews in Academic Philosophy Journals

- Are Mental Disorders Brain Disorders? by Anneli Jefferson is reviewed by Matthew Broome in Philosophical Psychology.

- Psychopathology and the Philosophy of Mind edited by Valentina Cardella and Amelia Gangemi is reviewed by Juliette Vazard in Philosophical Psychology.

Recent Philosophy Book Reviews in Non-Academic Media

- Wonder Struck: How Wonder and Awe Shape the Way We Think by Helen De Cruz is reviewed by Skye C. Cleary at The Wall Street Journal.

- Walter Benjamin and the Idea of Natural History by Eli Friedlander is reviewed by Sarah Moorhouse at the LA Review of Books.

- Who’s Afraid of Gender? by Judith Butler is reviewed by Jennifer Szalai at The New York Times.

Compiled by Michael Glawson

BONUS: Tickling and Personal Identity

The post Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update first appeared on Daily Nous.

Good Governance in Nigeria: Rethinking Accountability and Transparency in the Twenty-First Century – review

In Good Governance in Nigeria: Rethinking Accountability and Transparency in the Twenty-First Century, Portia Roelofs critiques conventional Western ideas of “good governance” imposed in Africa, and specifically Nigeria, through fieldwork and historical analysis. Stephanie Wanga finds the book a grounded and nuanced argument for alternative, locally shaped and socially embedded models of governance.

Good governance: a phrase laden with meaning and history. Good governance in Africa? Even more trouble at hand. Colonial and neocolonial projects in Africa have been justified in the name of good governance. However, to assume a sense of foreboding when one hears the phrase “good governance” is also to assume – and even to locate – its meaning in a particular provenance. This is exactly what Portia Roelofs, in her book Good Governance in Nigeria: Rethinking Accountability and Transparency in the Twenty-First Century, wants to trouble.

The author wants to draw out a re-conception of good governance: namely, as conceived of by everyday people rather than, say, the World Bank or other institutions whose projected definitions come with immense repercussions.

Roelofs, a lecturer in politics at King’s College London, has spent time in Nigeria, including undertaking research in the universities of Ibadan and Maiduguri. It is from her fieldwork in Nigeria that she wants to draw out a re-conception of good governance: namely, as conceived of by everyday people rather than, say, the World Bank or other institutions whose projected definitions come with immense repercussions. To do so, this work “places the voices of roadside traders and small-time market leaders alongside those of local government officials, political godfathers and technocrats…[theorising] ‘socially embedded’ good governance.” Using this method, she defends the argument that “power must be socially embedded for it to be accountable”, in opposition to those who cast social embeddedness as sullying politics and leaving room for all the varied forms of corruption that may hinder good governance.

If society and social demands might be seen as an enabler of corruption […] the necessary flip side is that it can also represent a constraint on the actions of those in power.

Indeed, Roelofs extends Peter Ekeh’s erudite analysis (in Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa) of a “third space” that defies the binaries of political science’s beloved public and private spheres. Ekeh presented a space from which Nigerian (and wider African) politics could be more fruitfully analysed, a space that was “neither absolutely rational-bureaucratic public authority [nor]…patrimonial authority conceived as the personal or individual authority of a Big Man’s private household”. Roelofs presents evidence that “points towards the existence of more social forms of governance which are neither personalistic […] nor ethnic, but speak to a more general sociality”, which provides the basis for the notion of governance that is “both public and yet includes some social elements and the further possibility that this may constitute good governance”. If society and social demands might be seen as an enabler of corruption (something that is not, the author reminds us, a uniquely African problem), the necessary flip side is that it can also represent a constraint on the actions of those in power. In fact, the insistence on detaching the state from its societal embeddedness increases the opacity and unaccountability of the state.

Roelofs’ methodology may be controversial to those devoted to hyper-abstraction, but for those of us who theorise as we live rather than save theory for the books, good governance must always be socially embedded. However, Roelofs is engaging with real biases that run deep in both political theory and development studies, and that have had immense consequences. As she writes, “While personal contact between voters and politicians is pathologized in scholarly analysis of Africa, it is celebrated by political scientists working in Western democracies.” Social-embeddedness has been a kind of dirty word in a lot of the mainstream writing on African politics – it is this entanglement of the political with the social that causes diagnoses such as “the cancer of corruption” and other terms that pathologise African politics every which way.

This is a book that is quite close to me in terms of method, as a person who roots herself primarily in political theory but believes ardently in the ways other methods and sources, including history and fieldwork, must educate political theory. Along with this, the book is supposed to demonstrate “the associated possibilities for decolonising the study of politics”. One might question the extent to which this book rigorously engages this latter goal, but it continues in the tradition of thinkers including Thandika Mkandawire (to whom the book is dedicated) and others like Ndongo Samba Sylla and Leonce Ndikumana.

Roelofs contests the dominant World Bank discourse on good governance that is projected as universally accepted and uncontroversial. She proposes an alternative mode of governance whereby the people decide for themselves the terms of engagement – something that the World Bank has in multiple, egregious ways denied the continent. This very act is noteworthy – the “problem” of African politics has been repeatedly deemed “too embedded in social and material relations”, leading to the oft-cited ills of neopatrimonialism, corruption, etc.

Roelofs is self-conscious of her position as a white woman trying to turn the tables on colonial, trope-filled discourse and asks for thoughts on how such a move might be more conscientiously made.

However, though this goal of challenging what good governance means is named explicitly at the outset, it would have been useful to see the precise ways in which the book operates as a (potentially) decolonial act. Roelofs is self-conscious of her position as a white woman trying to turn the tables on colonial, trope-filled discourse and asks for thoughts on how such a move might be more conscientiously made. Indeed, many have questioned how “Africanists” – often white, often working outside the continent – have positioned themselves at the centre of changing tides in African political discourse. The racial blindspots (or worse) underlying African Studies must be called out alongside those of the financial institutions; the neocolonial project is a concert of efforts.

The author hints at this issue, but often in diplomatic terms. As Robtel Neajai Pailey writes, one needs to “speak into existence the proverbial elephant in the room of development: race”. However, one must balance this move with the recognition that all of us, including white academics, are responsible for taking the decolonial bull by the horns – that one must not shirk responsibility via the false generosity of “making space” for “people of colour”. The hard work of taking responsibility and being responsible must be consciously and explicitly engaged.

Another danger the book sometimes falls into is to play up the narrative of what Africa can teach the world.

Another danger the book sometimes falls into is to play up the narrative of what Africa can teach the world. This viewpoint is problematic in that it may suggest a need to peg the meaningfulness of work done in Africa to its importance for the Big Bad West (and elsewhere). The greater purpose may instead be to unearth meanings that only have value locally, to study Africa for its own sake, and not for the West’s education. The question of where meaning should be focused relates to Toni Morrison’s observations on racism as a distraction. This burden leaves a person desperately trying to prove that they, too, are worthy; that they, too, have important things to show the world, unaware that by that very token they are upholding a particular standard of worthiness.

Despite this, Roelofs’ book serves as both rigorous, extended analysis of the good governance discourse and a worthwhile historical introduction to the troubles that have besieged state-making in Africa. Roelofs keenly dissects several key historical moments in Nigeria to tease out how they theoretically shape contemporary understandings of good governance.

Roelofs’ book serves as both rigorous, extended analysis of the good governance discourse and a worthwhile historical introduction to the troubles that have besieged state-making in Africa.

To this end, she writes about how good governance in Nigeria is often tied to the person (and myth) of Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who, to some, was the best President Nigeria never had. However, there is more to the picture than the “modernising, elite-led, progressive” elements that epitomise notions of good governance in Nigeria and that Awolowo represented. Working through the contested ideas that surround good governance, Roelofs comes up with what she calls the “Lagos model”. This is a homegrown approach, made of a shared set of reference points acting as a yardstick against which governance is evaluated. Roelofs names the reference points as “an epistemic claim to enlightened leadership, a social claim to being embedded in one’s constituency and a material claim about the sharing of resources”. Roelofs shows that the ideas of good governance grounded in epistemic superiority were in tension with more populist visions that emphasised the need for satisfying short-term economic desires and connecting with leaders. From this dialectic “a full and rounded picture of legitimate leadership as containing epistemic, social and material aspects” emerges. The struggle to balance each of these three aspects is what produces good governance, and the gaps in managing the give and take across the three is what gives various kinds of actors, nefarious and otherwise, entry to “fix” what appears broken.

Overall, the book is accessible and unpretentious, even while quite history-heavy. Though it may lack the poetry and passion of a Mudimbe or Mbembe, its appeal to democratise understandings of good governance demands the reader’s engagement reckon. It is a refreshingly democratic take on what it means to govern well, by rooting the definition in what everyday people in a specific context truly seek.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Tolu Owoeye on Shutterstock.

The Coalitions Presidents Make: Presidential Power and its Limits in Democratic Indonesia – review

Marcus Mietzner‘s The Coalitions Presidents Make examines Indonesia’s political transition, focusing on power-sharing arrangements and their impact on democratic reforms post-2004. Drawing on extensive qualitative data, Mietzner both sheds light on Indonesia’s particular case and reflects more broadly on coalition politics in emerging democracies, writes Yen Nie Yong. This post was originally published on the LSE Southeast Asia Blog.

The Coalitions Presidents Make is a welcome contribution to the analysis of the processes of political change in the emerging economies of East Asia and Southeast Asia, especially in light of Indonesia’s recent parliamentary and presidential elections.

The Coalitions Presidents Make is a welcome contribution to the analysis of the processes of political change in the emerging economies of East Asia and Southeast Asia, especially in light of Indonesia’s recent parliamentary and presidential elections.

Post-Suharto Indonesia is often portrayed as an era that ushered in the birth of a new presidential democracy in the country. However, the transition from a decades-old strongman regime – specifically one that bookmarks the turbulent period of postcolonial social and economic development and Suharto’s fall – was messy and remains incomplete. It is from this incompleteness that Mietzner began his comprehensive study on the coalition presidentialism of Indonesia from the year 2004 to its current state.

Mietzner utilis[es] data from over 100 qualitative interviews with not only the former and current presidents of Indonesia, but also various actors who are directly and indirectly involved in the process of coalition-building.

This monograph is aimed at readers familiar with the literature of coalition presidentialism within the field of Political Science and Indonesian Studies. However, as a researcher who primarily focuses on Malaysian companies in the postcolonial era, I found this book to be a page-turner, largely due to Mietzner’s adept narrative-building skills throughout the book. This is hardly surprising, as Mietzner offers details gleaned from more than two decades of observing the country’s democratic transition from a close-up view. Mietzner’s approach is also ethnographic, by utilising data from over 100 qualitative interviews with not only the former and current presidents of Indonesia, but also various actors who are directly and indirectly involved in the process of coalition-building. The amount of qualitative data accumulated is commendable, as access to the presidents’ inner circle generally requires years of effort in relationship-building, as well as the researcher’s discernment in knowing the difference between the true internal workings and smokescreens of Indonesia’s politics.

How have Indonesia’s presidents post-2004 managed to survive the perils of presidentialism, and what is the price for it?

Mietzner’s key research questions are fascinating – how have Indonesia’s presidents post-2004 managed to survive the perils of presidentialism, and what is the price for it? Indonesia, he argues, achieved more success in transitioning from an unstable presidential regime in the early post-Suharto period into a democracy that is among the world’s most resilient. This is mainly because of the informal coalitions with non-party actors who enjoy or covet political privileges such as the military, the police, oligarchs and religious groups. These actors require as much courting and co-opting as political parties and legislators, a key finding which current studies have ignored or downplayed. In each chapter, Mietzner explains the collective power of a political actor, and utilises a case study to link the phenomenon with his analysis, which I found to be compelling and clear. The locked-in stability created by the broad coalitions under Yudhoyono’s and Widodo’s presidency, nevertheless, had dire consequences in terms of stagnating reforms and democratic decline. Mietzner argues that Indonesia is a prime example of this phenomenon and ought to be a valuable lesson to be studied by those interested in presidential democracies globally.

Through reading this book, my impression is that the power-sharing arrangements between the president and his diverse coalition partners are akin to a prisoner’s dilemma. Mietzner argues that the incumbent president and his predecessor opted for this particular kind of accommodation because of perceived and imagined fears of what might happen to them if they were to choose the path of taking down these coalition partners. The coalition partners also appear to have taken a similarly defensive stance, thus perpetuating existing political arrangements among the actors at the expense of democratic reforms. This, Mietzner explains, is grounded in history, as both sides remain committed to upholding the image of the Indonesian presidency as the key provider of political stability. Many of the politicians and coalition partners lived through the Suharto years and learned how to “do politics” during that era, thus internalizing the appeal of working with presidents in power rather than working to overthrow them.

One element which Mietzner could have expanded upon in the book is how […] historical pathways have impacted on the current accommodation style between the president and non-party actors.

One element which Mietzner could have expanded upon in the book is how these historical pathways have impacted on the current accommodation style between the president and non-party actors. The relationship between the president and the oligarchs is particularly instructive in this regard, as Mietzner shows that in post-2004 coalitions, the oligarchs’ participation in coalition politics became “more direct, formal and institutionalized” (194). What happened during the transition years post-1998 that had enabled the oligarchs such access which was not available to them before? This context can help clarify if the pre-1998 accommodation between the president and capitalists were thoroughly dismantled, and if so, led to expansion of coalitions to other non-party actors after 2004. As history has shown, past strongman leaders in Asia (especially those who fought against colonialism) do not fade easily. The nostalgia for Suharto’s rule was also highlighted by the media during the 2014 presidential elections, elucidating how historical baggage constrains presidents from embarking on meaningful political reforms in this country.

The Indonesian case is an ideal one to expand conceptual boundaries in comparative studies of coalition presidentialism.

Does the specific context of Indonesia’s coalition presidentialism make this case an outlier and thus inapplicable to other democracies? Mietzner emphasises that the Indonesian case is an ideal one to expand conceptual boundaries in comparative studies of coalition presidentialism. As the bulwark of democracy in Southeast Asia, perhaps Indonesia may offer valuable insights beyond coalition presidentialism. As a novice reader on the conceptual theories of coalition presidentialism, I am also curious about whether this can also be relevant to other democracies in Southeast Asia, especially in the context of their shared postcoloniality. After all, the multiplicity of non-party actors in Indonesia’s context should also be situated in the diverse cultural identities of these actors and the postcolonial unsettledness of the nation’s identity. In his proclamation of Independence in 1945, Sukarno had famously used the acronym “d.l.l., or etc. in the Bahasa, which author and former journalist Elizabeth Pisani highlighted in her book Indonesia Etc: Exploring the Improbable Nation.

In Mietzner’s concluding chapter, he writes, “the more pressing challenge is to explore how coalitional presidentialism can work without sucking the oxygen out of democratic societies (245).” This is a conspicuous issue confronting not only Indonesia, but also its neighbouring democracies in the region. The revolving door of party and non-party actors in Indonesia highlights the precarious nature of the development of civil society in Southeast Asia. One can also see the parallels drawn in Malaysia’s coalition party politics, its longstanding stability, and the inclusion and exclusion of civic groups that have undermined the nation’s political progress for decades.

In this sense, Mietzner’s analysis of Indonesia’s coalition presidentialism is highly relevant for future research, as it presses upon researchers the important message to continue to investigate the undercurrents of other young, evolving and often fragile democracies in recent years.

Note: This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books blog as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia.

The review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image: Joko Widodo, the President of Indonesia

Image credit: Ardikta on Shutterstock.

Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update

The weekly report on new and revised entries at online philosophy resources and new reviews of philosophy books…

Reminder: if your journal publishes open-access book reviews, please send in links to them for inclusion in future weekly updates.

New: ∅

Revised:

John Dewey by David Hildebrand.

Immutability by Brian Leftow.

Margaret Fell by Jacqueline Broad.

The Possibilism-Actualism Debate by Christopher Menzel.

IEP ∅

NDPR ∅

Open-Access Book Reviews in Academic Philosophy Journals ∅

Recent Philosophy Book Reviews in Non-Academic Media

The Joy of Consent: A Philosophy of Good Sex by Manon Garcia and Consent Matters by Robert E. Goodin are together reviewed by Geertje Bol at The Times Literary Supplement.

Who Owns the Moon?: In Defence of Humanity’s Common Interest in Space by A.C. Grayling and A City On Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith are together reviewed by Erika Nesvold at The Times Literary Supplement.

God, Justice, Love, Beauty: Four Little Dialogues by Jean-Luc Nancy (translated by Sarah Clift) is reviewed by Molly Young at The New York Times.

Who’s Afraid of Gender? by Judith Butler is reviewed by Keith Contorno at Chicago Review of Books.

Compiled by Michael Glawson

BONUS: New argument for limitarianism

The post Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update first appeared on Daily Nous.

Tactical Publishing: Using Senses, Software, and Archives in the Twenty-First Century – review

In Tactical Publishing: Using Senses, Software, and Archives in the Twenty-First Century, Alessandro Ludovico assembles a vast repertoire of post-digital publications to make the case for their importance in shaping and proposing alternative directions for the current computational media landscape. Although tilting towards example over practical theory, Tactical Publishing is an inspiring resource for all scholars and practitioners interested in the critical potential of experimenting with the technologies, forms, practices and socio-material spaces that emerge around books, writes Rebekka Kiesewetter.

Working at the intersection of art, technology, and media, Alessandro Ludovico is known for his contribution to shaping the term “post-digital” through his book Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894. Ludovico’s notion of the post-digital, in brief, challenges the divide between digital and physical realms by exploring the normalisation and ubiquity of the digital in contemporary culture and urges for a nuanced perspective beyond its novelty, as boundaries between online and offline experiences blur.

Working at the intersection of art, technology, and media, Alessandro Ludovico is known for his contribution to shaping the term “post-digital” through his book Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894. Ludovico’s notion of the post-digital, in brief, challenges the divide between digital and physical realms by exploring the normalisation and ubiquity of the digital in contemporary culture and urges for a nuanced perspective beyond its novelty, as boundaries between online and offline experiences blur.

Tactical Publishing is presented as a sequel, evolving and updating Ludovico’s concept for the concerns of a contemporary computational media landscape shaped by technologies and platforms (social media, algorithms, mobile apps and virtual reality environments) owned by large multinational corporations. Through discussing a wide variety of antagonistically situated experimental and activist publishing initiatives, Ludovico discovers fresh roles and purposes for books, publishers, editors, and libraries at the centre of an alternative post-digital publishing system. This system diverges from the “calculated and networked quality of publishing between digital and print … to promote an intrinsic and explicitly cooperative structure that contrasts with the vertical, customer-oriented industry model” (8).

Ludovico develops this argument around a captivating array of well and lesser known examples from the realms of analogue, digital, and post-digital publishing stretching the prevalent boundaries of what a book was, is, and can be. Ranging from Asger Jorn’s and Guy Debord’s sandpaper covered book Mémoirs (1958), to Nanni Balestrini’s computer generated poem “Tape Mark 1” (1961), to Newstweek (2011), a device for manipulating news created by Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev. Tactical Publishing also ventures into the complex relationships, practices, socio-political and economic contexts of the production and reception of books. It draws on these relational contexts to explore their disruptive potential. For example, through forms of “liminal librarianship” practiced by DIY libraries, networked archiving practices of historically underrepresented communities, and custodianship in the context of digital piracy.

Ludovico develops this argument around a captivating array of well and lesser known examples from the realms of analogue, digital, and post-digital publishing stretching the prevalent boundaries of what a book was, is, and can be

As in Post-Digital Print, Tactical Publishing offers an abundantly rich resource for scholars interested in exploring the ways in which experimenting with the manifold dimensions that make up books, can be a means for creative expression, intellectual exploration, and social change in the digital age. Ludovico dedicates considerable attention to these case studies, allowing them ample space to shine and speak by themselves in support of his argument.

The book is divided into six chapters, each mixing illustrative instances of practical application with theoretical reflection. Chapter one explores how reading is transformed by digital screens. These, as the author explains, tend to enforce industrially standardised experiences, while neutralising cultural differences and leading to a potential loss of sensory involvement. Ludovico proposes to reclaim enriched and multisensory reading experiences by combining digital tools and physical qualities. He illustrates this proposition by discussing a series of publishing experiments in music publishing that have used analogue and digital technologies to integrate text and music media.

Chapter two examines the transformation of the role of software in writing. Here, Ludovico presents a transition from an infrastructural to an authorial function that blurs distinctions between human and artificial “subjectivities”. The latter being a simulation of human-like experiences, characteristics, and behaviours often associated with human subjectivity, such as learning, decision-making, or emotional responses. This simulation Ludovico argues increasingly obstructs the ability to distinguish between actions and expressions originating from humans and those generated by technological systems. Ludovico contends that the “practice of constructing digital systems, processes, and infrastructures to deal with these new subjectivities can become a political matter” (89). One that requires initiatives intertwining critical and responsible efforts in digitising knowledges, making digital knowledge-bases accessible and searchable, and developing and maintaining machine-based services on top of them. However, the origin and nature of these institutions, and what their efforts might entail remain unspecified.

Ludovico presents a transition from an infrastructural to an authorial function that blurs distinctions between human and artificial “subjectivities”.

Chapter three explores how post-truth arises from a constant construction and deconstruction of meaning in transient digital spaces, and through media and image manipulation. Ludovico emphasises that, in this context, it is important to build “an information dam … to protect our minds from being flooded with data, especially emotionally charged data” (123). Chapter four, “Endlessness: The Digital Publishing Paradigm”, makes the case that the fragmented short formats characteristic of digital publishing underscore the importance of the archival role of print publications and the necessity of networks of “critical human editors” (130). These can act as a counterbalance to this flood of information and foster a more focused and collaborative exchange of information.

Chapter five proposes a transformation of libraries from centralised towards distributed and networked knowledge infrastructures in which librarians strategically contribute to the selection and sharing of “relevant collections” (197). Chapter six concludes Tactical Publishing synthesising the previous chapters by proposing the strategic integration of analogue and digital realms within an “open media continuum” rejecting a calculated, networked approach in favour of a cooperative structure sustained by “responsible editors” (212), publishers, librarians, custodians, and distributors. Last but not least, a useful appendix offers a selection of one hundred publications, encompassing both print and digital formats.

Tactical Publishing sits within a well-established canon of critical media studies, digital humanities, and cultural studies, focusing on the materiality of media, historical dimensions of technology, media ecology, politics of information, and socio-cultural implications of post-digital communication. However, its theoretical contributions are at times subdued by the host of examples presented. Some readers may also be left wanting a more pronounced engagement with recent theoretical works discussing the concept of post-digital publishing and its interventionist potential into dominant publishing systems, norms, and cultures from cultural hegemony critical, post-Marxist, various feminist, post-hegemonic, and ecologically-minded perspectives. Such an engagement might have helped clarify questions about the politics and ethics related to the alternative post-digital publishing system and the “comprehensive liberatory attitude” (4) Ludovico advocates for, beyond the motivation to counter the alienation of the current computational media landscape.

Tactical Publishing sits within a well-established canon of critical media studies, digital humanities, and cultural studies, focusing on the materiality of media, historical dimensions of technology, media ecology, politics of information, and socio-cultural implications of post-digital communication.

Similarly, Tactical Publishing also leaves unresolved related questions of positionality, accountability, and agency. For example: Who is the “we “Ludovico addresses, not least in the final chapter titled “How we Should Publish in the 21st Century”? What drives “the critical human editors” (130) whose role is to “filter the myriad of sources, to preserve their heterogeneity, to … include new sources, but to keep their final number limited, and to confirm them, transparently acknowledged, in order to strengthen trusted networks” (211), and what legitimises their activity? And where, in a post-digital world, is “the personal trusted human network” situated that, according to the author, can be “resistant to mass manipulation by fake news and post-truth strategies” (123)?

However, despite (or exactly because) the theoretical argument occasionally takes a backseat to numerous meticulously selected and well-arranged examples, Tactical Publishing is an inspiring resource for all scholars and practitioners in design, the arts, humanities, and social sciences that are interested in the ways in which experimental publishing can help question, challenge and rearrange dominant publishing systems.

Note: This article was initially published on the LSE Impact of Social Science blog.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Dikushin Dmitry on Shutterstock.

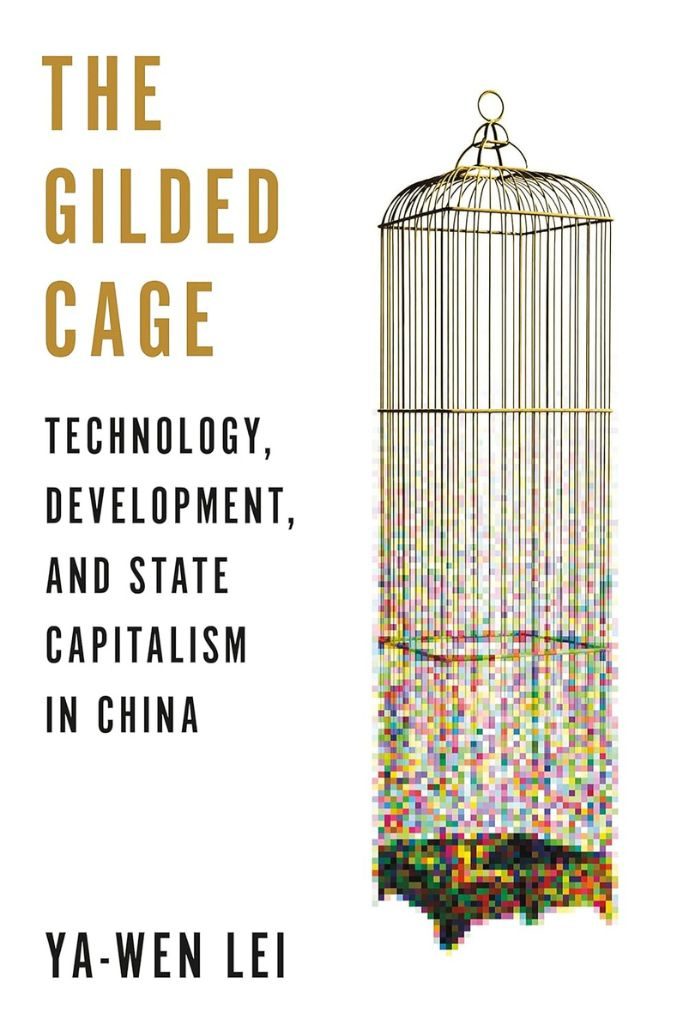

The Gilded Cage: Technology, Development, and State Capitalism in China – review

In The Gilded Cage: Technology, Development, and State Capitalism in China, Ya-Wen Lei explores how China has reshaped its economy and society in recent decades, from the era of Chen Yun to the leadership of Xi Jinping. Lei’s meticulous analysis illuminates how China’s blend of marketisation and authoritarianism has engendered a unique techno-developmental capitalism, writes George Hong Jiang.

Twenty years ago, people inside and outside China were wondering whether the country would eventually capitulate to dominant capitalist and democratic models. American politicians such as Bill Clinton were enthusiastically looking forward to the future integration of China into globalisation. When this happened, millions of ordinary people would get rich and become the middle class through fast-growing international trade and domestic labour-intensive industries. However, this judgment quickly proved ill-made. China has simultaneously emulated the US in high-tech industries but also become an unparalleled authoritarian state which polices its citizens through intellectual technology and high-tech instruments. How has it achieved this, and what are the effects of this? Lei tries to untangle these questions in her book, The Gilded Cage: Technology, Development, and State Capitalism in China.

Twenty years ago, people inside and outside China were wondering whether the country would eventually capitulate to dominant capitalist and democratic models. American politicians such as Bill Clinton were enthusiastically looking forward to the future integration of China into globalisation. When this happened, millions of ordinary people would get rich and become the middle class through fast-growing international trade and domestic labour-intensive industries. However, this judgment quickly proved ill-made. China has simultaneously emulated the US in high-tech industries but also become an unparalleled authoritarian state which polices its citizens through intellectual technology and high-tech instruments. How has it achieved this, and what are the effects of this? Lei tries to untangle these questions in her book, The Gilded Cage: Technology, Development, and State Capitalism in China.

The author was inspired by the “birdcage economy” of Chen Yun when choosing the title of the book.[…] Statist control is the cage, and private economies, like captive birds, are only allowed to fly within the cage.

The author was inspired by the “birdcage economy” of Chen Yun when choosing the title of the book (5). Building the planned economy in the early 1950s and supporting economic reforms in the 1980s, Chen Yun was one of the most important architects of economic systems in communist China. While he was a proponent of giving more space to private economies, Chen Yun staunchly believed in the efficacy of governmental regulations. Statist control is the cage, and private economies, like captive birds, are only allowed to fly within the cage. Chen Yun was particularly cautious about liberalist reforms, such as deregulation of finance and fiscal decentralisation, and distinctly opposed to privatisation. After he died in 1995, Deng Xiaoping and his disciples, including Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, carried out deregulation bravely until the late 2000s. But the ideal of Chen Yun’s “birdcage economy” is never abandoned by communists who fear losing control over the society.

The 2008 financial crisis started China’s big turn of macroeconomic policies. In order to stimulate the deflated economy, the government reacted fast and invested enormous capital into a few key strategic industries, including bio-manufacturing industry and aircraft and electronic manufacturing. Ling & Naughton (2016) believe that this action signalled the watershed of China’s economic orientation. The government’s budget poured into these industries, and bureaucratic units responsible for supervision and regulation turned to interventionist policies. The trend was further strengthened after Xi Jinping, who believes that the combination of the free market economy and Leninist political principles is the best blueprint for China, ascended to the presidency in 2012.

New leadership since the 2010s wants to emulate western high-end development rather than provide low-end, cheap and labour-intensive products for the West.

The ambition to develop high-tech industries runs in tandem with the unique political system of China. Economic growth has helped sustain political legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since the 1980s. Since socialism was smeared by the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and its disastrous economic consequences, economic growth has been identified as the most important source of political legitimacy. Economic performance has become the indicator of bureaucratic promotion, which has fused China’s politics and economies together. This political organisational mechanism makes it easier for leaders to push through any desired change and it is on this that China’s turn to techno-development (Chapter Three) is precisely based. New leadership since the 2010s wants to emulate western high-end development rather than provide low-end, cheap and labour-intensive products for the West.

Still, a key question must be answered: why are Chinese bureaucrats who care primarily about social stability and political monopoly willing to replace human labour with robots, which tends to reduce employment in the short run? In Chapter Five, the author traces the process of robotisation in firms which previously rely on cheap labour, including Foxconn. While the benefits of robotisation might be obvious to entrepreneurs aspiring to reduce costs by any means, potential instability could cause trouble for communist bureaucrats. The answer lies in the possibility that technological upgrades will lead to an enlarging economy capable of digesting more workers than it kicks out. However, it results in a dilemma: if the growth rate slows down, the appetite for mechanisation and robotisation could stir social tensions.

Seeing the chance to surpass the West in the development of high-tech industries, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is more than willing to strengthen control over public spheres and civil society and increase investment in the sector to achieve this.

Seeing the chance to surpass the West in the development of high-tech industries, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is more than willing to strengthen control over public spheres and civil society and increase investment in the sector to achieve this. As the author puts it, “the Chinese state is an unwavering believer in intellectual technology and instrumental power and employs both to enhance governance and the economy” (9). It is highly possible that with the help of an authoritarian regime and its will to develop technological capability, the dismal future that Max Weber once predicted – ie, the “iron cage of bureaucracy” in which depersonalised and ossified instrumental rationality will dominate every sphere in the society – will come sooner in China than in the West.

Economic growth is mainly driven by high-tech industries that private and state-owned capital foster, both of which must be under the control of the government, with the unified aim of rejuvenating the Chinese nation.

Karl Marx argued that productive power, including technological conditions, determines relations of production. This idea is being justified in China. A mix between marketised economies and authoritarian rule, which is penetrated by high-tech instruments, facilitate the rise of techno-developmental capitalism, as the author proposes in Chapter Nine. On the one hand, large tech companies in China have hatched one of the biggest markets in the world. On the other hand, tech professionals’ increasing demand for institutional (if not political) reforms (Chapter Eight) renders bureaucrats gradually more concerned about their social influence. For instance, Jack Ma, the boss of Alibaba, attacked the state-owned financial system and instantly got punished by the authority. China is developing a new variant of capitalism: economic growth is mainly driven by high-tech industries that private and state-owned capital foster, both of which must be under the control of the government, with the unified aim of rejuvenating the Chinese nation.

Techno-developmental capitalism is not the result of contingency, but path-dependent outcome, the direct result of China’s polities.

The author includes an excellent range of relevant materials into the book, spanning academic literature and personal interviews with private entrepreneurs and IT practitioners. Lei also bravely applies the term “instrumental rationality” in relation to China’s socioeconomic reality. In so doing she identifies the Janus-faced nature of China’s technological development, whereby the society enjoys higher productivity but becomes more rigid and occluded due to the omnipotent techno-bureaucracy. Nonetheless, the book could have been improved if Lei could take China’s political-economic structure into account when explaining the motivation to develop high-tech industries. While Lei focuses on the era after the 2000s, the rise of techno-developmental capitalism is deeply rooted in the persistent logic of the CCP since the late 1970s. In other words, techno-developmental capitalism is not the result of contingency, but a path-dependent outcome, the direct result of China’s polity. In spite of this lack of fully examined historical dimensions, Lei presents a good guidebook for China’s holistic development, not just within the last two decades but also in the decades to come.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: B.Zhou on Shutterstock.

Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update

The weekly report on new and revised entries at online philosophy resources and new reviews of philosophy books…

Reminder: if your journal publishes open-access book reviews, please send in links to them for inclusion in future weekly updates.

New: ∅

Revised:

- Zhuangzi by Chad Hansen.

- Kumārila by Daniel Arnold.

- Law and Ideology by Christine Sypnowich.

- Modal Fictionalism by Daniel Nolan.

- Time Travel by Nicholas J.J. Smith.

- Social Epistemology by Cailin O’Connor, Sanford Goldberg, and Alvin Goldman.

- Pierre Gassendi by Saul Fisher.

- Location and Mereology by Cody Gilmore, Claudio Calosi, and Damiano Costa.

IEP ∅

NDPR ∅

Open-Access Book Reviews in Academic Philosophy Journals ∅

Recent Philosophy Book Reviews in Non-Academic Media

- Wonderstruck: How Wonder and Awe Shape the Way We Think by Helen De Cruz is reviewed at Publishers Weekly.

- Who’s Afraid of Gender? by Judith Butler is reviewed by Becca Rothfeld at The Washington Post, and by Pamela Stewart at The Post-Gazette.

- Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth by Ingrid Robeyns is reviewed at The Economist.

Compiled by Michael Glawson

BONUS: No reason

The post Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power – review

Caty Borum‘s The Revolution Will Be Hilarious: Comedy for Social Change and Civic Power considers how comedy intersects with activism and drives social change. Borum’s accessible text draws from case studies and personal experience to demonstrate how comedy can successfully challenge norms, amplify marginalised voices and foster dialogue on issues from racism to climate change, writes Christine Sweeney. This … Continued

Reclaiming Participatory Governance: Social Movements and the Reinvention of Democratic Innovation – review

In Reclaiming Participatory Governance, Adrian Bua and Sonia Bussu bring together analyses of social movements around the world that engage with democracy-driven or participatory governance. Although the essays in this volume reveal the challenge of bringing grassroots organising into our political systems, they advocate compellingly for nurturing these practices to create fairer and stronger democracies, writes Andrea Felicetti.

Reclaiming Participatory Governance is a compelling investigation of the potential for bottom-up forms of democratic innovations to vitalise our democracies. Anchored on Adrian Bua and Sonia Bussu’s concept of “democracy-driven governance” (DDG), this edited volume critically investigates the “potential, limits and opportunities” of social movements’ engagement with participatory and deliberative institutional designs. This is no small feat since social movements and democratic innovations are often seen as crucial in strengthening our democracies.

Reclaiming Participatory Governance is a compelling investigation of the potential for bottom-up forms of democratic innovations to vitalise our democracies. Anchored on Adrian Bua and Sonia Bussu’s concept of “democracy-driven governance” (DDG), this edited volume critically investigates the “potential, limits and opportunities” of social movements’ engagement with participatory and deliberative institutional designs. This is no small feat since social movements and democratic innovations are often seen as crucial in strengthening our democracies.

[Democracy-driven governance] is considered in its capacity for effectively ‘[o]pening up spaces for a deeper critique of minimalist liberal democratic institutions and the neoliberal economy that underpins them’.

From the introduction, expectations are high. Pitted against forms of “governance-driven democratisation” (GDD) that tend to be seen as top-down and markedly bureaucratic, DDG is considered in its capacity for effectively “[o]pening up spaces for a deeper critique of minimalist liberal democratic institutions and the neoliberal economy that underpins them”. Of course, this needs to occur at a time when “space for meaningful citizen input is increasingly constrained by technocratic decision-making and global economic pressure”.

The book presents a highly coherent and impressive collection of in-depth analyses that span theory and empirical research, with a great variety of cases. Spain takes centre stage, and there are no case studies from English-speaking countries, going markedly against the tide. Theory is at the heart of the first section. Drawing from fascinating cases in Germany and Iceland, Dannica Fleuss shows the urgency of thinking about democracy beyond liberal institutions. Nick Vlahos introduces the idea of “participatory decommodification of social need” as an interesting way to think about how participatory governance can combat the worst effects of capitalism, with examples from Toronto, Canada. Based on his extensive fieldwork in Rosario, Argentina, Markus Holdo discusses the concept of “democratic care” to unearth the work performed by activists that needs to be recognised in participatory governance. Finally, Hendrik Wagenaar offers a compelling analysis of strengths and weaknesses of the GDD/DGG pair from a political economy standpoint, building on a well-established threefold distinction between the dominant economic, financial system, the political, administrative sector and civil society.

Vlahos introduces the idea of ‘participatory decommodification of social need’ as an interesting way to think about how participatory governance can combat the worst effects of capitalism

The second part is markedly empirical. Paola Pierri analyses the Orleans Metropole Assise for the Ecological Transition, in France, showing a case of “collaborative countervailing power” that reminds us that the seminal work of Empowered Participatory Governance by Archon Fung and Erik Olin Wright remains highly relevant to understand participatory governance. Lucy Cathcart Frodén investigates the parallels between prefigurative social movements and participatory arts projects as well as their potential to contribute to democratic renewal. A rather effective collaboration between “right to the city” activists and local administration is documented in Roberto Falanga’s in-depth analysis of the participatory process for the regeneration of one of the main squares in Lisbon, Portugal. Giovanni Allegretti shows clearly how anticolonial protests irrupt into and benefit participatory experiments in Kalaallit Nunaat, Greenland. Mendonça and colleagues, instead, systematically explore strengths and weaknesses of Gambiarra, an unconventional means social movements in Brazil use to break into elites-dominated elections at local and parliamentary level. Bua, Bussu and Davies offer the ultimate comparison about the GDD and DGG models as embodied in the historical trajectories of participatory governance of the cities of Nantes and Barcelona respectively.

The third section highlights problems and limitations. Joan Balcells and colleagues unveil the tension that lay at the basis of the famous participatory platform Decidim. Always focusing on Barcelona, Marina Pera and colleagues look at the Citizen Assets Program showing how lack of trust prevented this very advanced form of democratisation from being embedded into its context. Fabiola Mota Consejero considers another case from Spain where Madrid’s progressive local government broke with a longstanding tradition of conservative patronage but failed to turn its main innovation, Decide Madrid, into an effective means for participatory governance. Patricia Garcia-Espin, instead, shows the fatigue and disappointment of activists involved in another innovation of Madrid’s new municipalist government, the local forums. Finally, Sixtine Van Outryve looks at a fascinating case of a local Yellow Vest organization in Commercy, France, trying to set up an open citizens assembly to have a communalist project represented in the local government that ultimately failed.

Virtually every chapter of this book details a host of challenges participatory governance faces in the context of minimalist democracies dominated by neoliberal economics.

The findings in this book are rather sobering. Employing a rigorous approach devoid of self-celebration or ideological dismissal, virtually every chapter of this book details a host of challenges participatory governance faces in the context of minimalist democracies dominated by neoliberal economics. In many case studies, elements of both GDD and DGG coexist, and sometimes one morphs into the other. Second, empirical investigations highlight weaknesses with DGG. This reduces our expectations about this model of democratisation, yet it also lends it a more realistic and useful outlook. Third, while the theoretical section highlights the political economy of participatory governance as a crucial issue, that remains in the background in the empirical analysis, as it tends to happen in the field. This kind of investigation remains essential.

Further, after reading this book, one has the feeling that contemporary participatory governance grapples with two important limitations. First, the promotion of participatory governance remains primarily within the purview of a select group of political actors: progressive parties, particularly those with a robust radical left presence. As we move to the centre of the political spectrum, the idea of reinvigorating democracy, let alone doing so by means of radical participatory governance, seems to lose attractiveness. Indeed, the book consistently shows that, in those uncommon cases in which progressive parties that champion participatory governance take power, they downscale their democratisation ambitions as they face the challenges implied in participatory governance. These can vary from administrative hurdles in implementing innovation to more endogenous problems relating, for example, to internal conflicts arising from differing conceptions of democracy that exacerbate fatigue and disillusionment. Second, the book gives the sense that contemporary participatory governance still has a mass democracy problem. It is still missing any substantial connection with the public at large. Except for occasional influence during electoral campaigns, none of the studied experiments have garnered sustained support or substantial interest from the public at large.

This volume stands as proof of the ongoing efforts to use participatory governance in critical and democratising ways around the world

This might seem disheartening, especially because there is no practical solution in sight. The electoral defeat of Spanish municipalism, central to this book, heightens this sensation. Yet, there is not much use in despairing, and a temporal prospective might offer some hope. As Gianpaolo Baiocchi reminds in his refreshing concluding remarks, it is not so long ago that the idea of participatory democracy made its irruption in our democracies. Initially championed by social movements and to a lesser extent Left political projects in the 1960s, this idea was later taken up by mainstream policymakers and international agencies. Unsurprisingly, participatory governance has not been able to singlehandedly compete with the broader political trend towards neoliberal governance; indeed, it has had to adapted to it to some extent. The resistance it meets today shows major limitations. Yet, this volume stands as proof of the ongoing efforts to use participatory governance in critical and democratising ways around the world. It also speaks to the fact that there is great social scientific scholarship trying to understand and strengthen this phenomenon.

The book often refers to the value of learning from and with activists. Indeed, one of its the most significant contributions is its ability to forge an expanded understanding of participatory governance.

The book often refers to the value of learning from and with activists. Indeed, one of its the most significant contributions is its ability to forge an expanded understanding of participatory governance. This volume goes beyond the perpetual dispute between different conceptions of democracy. It shows how participatory governance todays draws from a rich tapestry of diverse ideas and practices – both old and new. The fact that concepts such as “care”, the “right to the city”, “communalism”, “new municipalism”, “gambiarra” and “decolonisation” are brought together in this volume speaks to the eclectic nature and vitality of contemporary participatory governance. Despite its challenges, participatory governance continues to attract the ingenuity of people and their eagerness for democracy. Persistence is crucial, as these are fundamental ingredients in the struggle to build a more equal and just world.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Dedraw Studio on Flickr.

Blurring Boundaries – ‘Anti-Gender’ Ideology Meets Feminist and LGBTIQ+ Discourses – review

In Blurring Boundaries – ‘Anti-Gender’ Ideology Meets Feminist and LGBTIQ+ Discourses, Dorothee Beck, Adriano José Habed and Annette Henninger assemble essays that conceptualise and reflect on emerging anti-gender, anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies and explore means of resisting them. These methodologically diverse (though geographically limited) interventions offer critical insights on how blurring discursive boundaries and building coalitions can combat anti-gender and other discriminatory movements.

As the movements against women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights continue, alarmingly, to gather momentum, how can scholars and researchers fight back? This is the question which animates the contributions collected in Blurring Boundaries – ‘Anti-Gender’ Ideology Meets Feminist and LGBTIQ+ Discourses.

As the movements against women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights continue, alarmingly, to gather momentum, how can scholars and researchers fight back? This is the question which animates the contributions collected in Blurring Boundaries – ‘Anti-Gender’ Ideology Meets Feminist and LGBTIQ+ Discourses.

In their introductory essay, editors Adriano José Habed, Annette Henninger and Dorothee Beck offer readers a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on anti-gender, anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies. Importantly, they emphasise the ethnocultural underpinnings of such discourses, arguing for “new forms of coalitional politics” to counter broader crises of governance, representation and identity within liberal democracies. Hence, the editors propose “blurring boundaries” as a means of first identifying the specific manifestations of anti-gender, anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQIA+ discourse, so as to better understand, and thus, combat them. They argue, for instance, against assuming that anti-feminism and anti-genderism do not share points of overlap with Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminism (TERF) positions on the basis of terminology (so-called “gender critical” feminists invoke the mantle of feminism, after all). They caution, too, against making value judgements as to what constitutes “good” or “bad” politics. Laudable as this critical nuance is, however, I cannot help but wonder, as a trans* reader, if sometimes we cannot simply call a spade a spade: the Holocaust denialism often espoused by TERF figures, to give but one example, is morally indefensible.

The collection’s strength lies above all in the diverse array of methodologies used. Each essay is meticulously researched, exhibiting a forensic attention to detail and a robust commitment to self-reflexivity

The collection’s strength lies above all in the diverse array of methodologies used. Each essay is meticulously researched, exhibiting a forensic attention to detail and a robust commitment to self-reflexivity. In the spirit of the editors’ introduction, the authors challenge assumed boundaries: Judith Goetz, for instance, considers the seldom-discussed role of transgender persons in far-right movements through a study of Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Goetz proposes the term “trans-chauvinism” to describe the racialised vision of German identity, and national superiority, which trans* individuals use to distinguish themselves from the “Muslim Other” (and, marshalling dualist, transnormative arguments, from “bad” trans* subjects, too). Patrick Wielowiejski and Edma Ajanović examine similar discursive turns in their analyses of ethnosexism (the ways in which ethnicised “Others” are painted as regressive or violent in their attitudes to sex, gender and sexuality) and femonationalism, defined by Ajanović as “the instrumentalization of feminist themes to promote racism as well as join the broader trend of Muslim and anti-migration/asylum discourses”, within the AfD and the Austrian Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), respectively. In particular, Wielowiejski’s Gramscian diagnosis of a far-right, ethnosexist “common sense” proves revelatory. Elsewhere, Gadea Méndez Grueso makes a compelling argument for understanding both “anti-gender” and TERF movements through the lens of populism studies – a perspective which, going beyond the often-restrictive labels of left and right, might better equip us to combat anti-trans* and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies.

Gadea Méndez Grueso makes a compelling argument for understanding both “anti-gender” and TERF movements through the lens of populism studies – a perspective which, going beyond the often-restrictive labels of left and right, might better equip us to combat anti-trans* and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies.

As Méndez Grueso’s contribution reminds us, scholarly investigation into such movements cannot afford to abstract itself from the urgent material contexts of its production and dissemination. Funda Hülagü’s chapter is a masterful example of how scholarship can, and should, speak directly to a collective project of political emancipation. Hülagü examines the “discursive entanglements” between contemporary anti-feminism and popular feminism in Turkey, offering a concise analysis of the specific modes of household formation and neoliberal governance presently operative in the country. Hülagü calls for an “offensive” activism which critically examines “the social core of very social problems” – in short, for an entirely new approach to conceptualising the ongoing “crisis of social reproduction” in the country, eschewing the psychologising and moralising frameworks of the present debate. Somewhat frustratingly, given the scope of the volume as a whole, Hülagü’s analysis says little about queer and trans* domesticities; Dilara Çalışkan’s research into the kin-making practices of transgender mothers and daughters in Istanbul, for instance, might provide an intriguing counterpoint to an otherwise heteronormative narrative, allowing us to sketch out what a trans-inclusive feminist movement might look like in the Turkish context.

The transnational dimensions of the anti-gender movement have been well documented, and whilst not entirely absent from the discussion, these broader currents merit further comparative analysis along the lines drawn

To be sure, Hülagü’s intervention is also conspicuous in that it breaks with a troubling emphasis on western European experiences in this collection. In what is perhaps a reflection of the editors’ own research networks, perspectives from German-speaking regions are somewhat overrepresented, accounting for more than half of the case studies under examination. This is not to deny the vital import of each individual contribution; nonetheless, this geographical skewing affords limited space to studies of anti-LGBTQIA+ and anti-feminist politics outside western Europe (nor, indeed, to the powerful writing emerging in Francophone and Scandinavian contexts). Instead, this project of Blurring Boundaries leaves national borders largely intact. The transnational dimensions of the anti-gender movement have been well documented, and whilst not entirely absent from the discussion, these broader currents merit further comparative analysis along the lines drawn, in this collection, by Christine M. Klapeer, Inga Nüthen and Maryna Shevtsova; forthcoming works by Judith Butler and Susan Stryker – pioneering voices in queer and trans studies, respectively – may prove useful to read alongside the essays collected in this volume.

In the continuing struggle against misogyny, transphobia and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies, we would do well to draw on the vigilance and care which these essays exemplify.

Hopefully, the publication of Blurring Boundaries will galvanise further research at this pivotal moment for feminism, as well as for queer and trans studies. Expanding our scholarly perspectives is essential if we are to avoid the “blind spots” of our own research, as Koen Slootmaeckers reminds us in the roundtable discussion which closes out the volume. What is less certain, however, is the role which “blurring boundaries” might come to play in this – a question broached by Henninger and Slootmaeckers in that same conversation. I am minded to agree with Slootmaeckers’ suggestion, that this somewhat nebulous phrase be taken up as an “invitation to reflect” on our own analytical approaches, rather than serving as an analytical concept in its own right. Ultimately, Blurring Boundaries is a collection of great import for scholars and activists alike. In the continuing struggle against misogyny, transphobia and anti-LGBTQIA+ ideologies, we would do well to draw on the vigilance and care which these essays exemplify. To do so is to reaffirm a shared commitment to political liberation in these most urgent of times.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Julia Tulke on Flickr.