Ancient Greece

Sortition for a Steady State Economy?

by Gary Gardner

Blindfolded, the more to be trusted? (Tim Green, Wikimedia)

In my frustration over humanity’s sluggish response to the urgent issues of our time, I find a bit of hope in an idea championed by the philosopher John Rawls. He had a simple and appealing suggestion for shifting people’s preferences in the direction of the common good.

Rawls proposed that anyone deliberating about public matters start from behind a “veil of ignorance.” In this position, legislators and other public actors are unaware of their place in society. They don’t know their level of wealth, their race, religion, social status, or sexual orientation. As a result, they don’t know how proposed policy choices would affect them.

Instantly, the veil drives decision-makers toward positions favoring the common good, mutual benefit, and equal opportunity. Behind the veil, what’s best for oneself is what’s good for all. Rawl’s suggestion is like parental guidance to kids salivating over a freshly baked pie: “One cuts, the other chooses.” Suddenly both kids’ interests align.

The challenge is to operationalize the veil of ignorance in policymaking. We can’t climb into the minds of legislators and erase their identity and interests. But we can use an indirect strategy: revive the ancient practice of sortition.

Donning the Veil

Sortition is the process of choosing our governing class by lottery rather than election. In a sortition system, all eligible citizens have essentially an equal chance of serving in a governing capacity because they are chosen by lot. The idea is unorthodox, to be sure, but it’s not crazy: Most U.S. jurisdictions use lotteries to choose juries. Average citizens seem to perform competently in judging their fellow citizens in criminal matters.

Moreover, sortition is arguably the most democratic form of governance. David van Reybrouck, author of Against Elections: The Case for Democracy, quotes no less an authority than Aristotle to make the case. “The appointment of magistrates by lot is democratical, and the election of them oligarchical,” Aristotle wrote. Van Reybrouck agrees. He writes that the choice of election-based democracy in the past few hundred years was a deliberately anti-democratic move engineered by elites. By designing governing structures to serve the interests of the economically powerful (like white, male property-owners in the early USA), electoral systems served as a buffer between the majority of people and the policymaking process.

A kleroterion, used for random selection of officials and jurors in Athens (Museum of the Ancient Agora, Wikimedia)

The government of ancient Athens was populated nearly entirely by citizens chosen through sortition. A stone device called a kleroterian was used to choose citizens for service. Chosen citizens served in one of the four main organs of governance: the Council of 500, which prepared the governing agenda; the People’s Assembly, a 6000-person body that adopted policies; the People’s Court, another 6000 or so people who pronounced judgment at trials and assessed the legality of laws; and the Magistracies, 600 or so people chosen by lot plus 100 elected by the People’s Assembly, which administered decisions.

Given the large number of positions across Athens’ governing institutions, the odds of eventually serving in office were high. Van Reybouck estimates that 50 to 70 percent of Athenian males over the age of 30 had once sat on the Council of 500. High levels of participation (at least among non-enslaved males) created a strong civic culture among citizens that reduced dramatically the distance between policies made and people affected. Athenians knew what it meant “to govern and to be governed,” in the words of Aristotle.

Another key feature of Athens’ citizen-governors is that they rotated through governance positions, many serving in all four of the major governing institutions. Rotations could be short. An extreme example is the People’s Court, whose membership changed daily, with lots drawn each morning among those present. Frequent change of officeholders reduces the potential for a concentration of special interests.

Sortition Rising?

Today, governance by lottery is rare, and is more likely to advise policymakers than to produce legislation. But sortition is having a moment, and arguably a real impact on policy, even on major issues like the climate crisis, environmental degradation, and yes, economic growth.

Ireland offers an inspiring case. In 2012 the national government began a process of convening citizens’ assemblies to discuss national policies and amendments to Ireland’s constitution. Since then, the government has called several other assemblies. Analysts credit each assembly with driving changes in policy on matters of consequence including marriage equality and voting rights.

The 2022 citizens’ assembly, focused on biodiversity, was highly representative. It opened eligibility to any adult resident of Ireland, not just citizens. And in contrast to the first assembly in 2012 when a third of participants were selected by political parties, all participants in the 2022 biodiversity assembly were randomly selected individuals.

Here’s how the selection process worked. Organizers sent invitations to 20,000 randomly selected households asking them to consider becoming an assembly member. More than ten percent of the 20,000 households expressed a desire to participate, a rate higher than the 3–5 percent typical of citizens’ assemblies internationally. From these, organizers applied demographic criteria to a random sorting process to arrive at the 100 assembly members.

Mapping the recruitment process for citizen’s assemblies in Ireland.

The 2022 biodiversity assembly made 73 high-level recommendations and 86 sector-specific recommendations, publishing the vote totals for each. It recommended that constitutional amendments granting citizens the right to “a clean, healthy, safe environment” and to “a stable and healthy climate” be placed before the people of Ireland as a referendum.

Perhaps most startling was this remarkable recommendation: “State should advocate for a shift in emphasis in EU and international economic policy away from GDP expansion as a goal in itself and towards the goals of societal and ecological wellbeing” (emphasis added).

There it is: the kind of visionary policy seldom seen in parliaments, congresses, or other elected bodies. This bold and far-reaching recommendation emerged organically after just nine months of deliberation among ordinary citizens. The ball is in the government’s court to follow up.

The outcomes of the Irish citizen assemblies suggest that people free to speak for themselves and deliberate with compatriots embrace ideas that otherwise don’t get a hearing in modern representative democracies. And they seem to settle on common-sense recommendations.

This is partly because assembly designers structured the groups to preclude special interests from influencing the deliberations. Organizers made public all submissions used in the assembly process (typically expert presentations), and they live-streamed sessions to the public. Moreover, assembly members would not face voters in a future election, allowing them to focus on the issues at hand.

Climate Policy by Chance

Beyond Ireland, citizen assemblies have weighed in on climate policy. A 2023 study compared recommendations of citizen assemblies to commitments found in the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) of ten European countries and the European Union as a whole). The researchers focused on the prevalence of “sufficiency proposals” in the citizen assemblies and NECPs of each of the eleven jurisdictions.

Could sortition deliver a right to repair? (Kumpan Electric,Unsplash)

Sufficiency proposals are regulations and incentives that aim for absolute reductions in consumption and production through behavioral changes (rather than technological ones). Examples include policies to reduce living space per person, curb meat consumption, ban environmentally damaging goods, and reduce materials demand by increasing the repairability of goods and discouraging the use of disposable products. Because sufficiency proposals do not embrace notions of green growth, they are likely to be consistent with steady state economies.

Citizen assemblies recommended sufficiency measures at a much higher rate than NECPs did, 39 percent to 8 percent. Moreover, assembly members voted in favor of sufficiency measures by majorities of at least 90 percent. And the citizen assemblies bore policy fruit. Remember the 2023 decision to ban short flights in France? That came about after a citizens’ assembly recommended it.

Other citizen assemblies in France and the UK have focused on climate recommendations, and on the reforms to the food system. And the assembly idea recently went global, at the COP26 climate conference in 2021. Participants for the Global Assembly’s core group were chosen from randomly selected population centers, with proportional representation by region.

They spent 11 weeks in late 2021 deliberating the question, “How can humanity address the climate and ecological crisis in a fair and effective way?” The assembly produced a Global Declaration, which avowed that “Nature has intrinsic values and rights” and called for legally binding measures to protect nature from “ecocide.” The group’s vision is to make the Assembly an annual gathering, with ten million participants by 2030.

The Fine Print

No modern democracy has handed over national-level governing functions to randomly selected citizens as the Athenians did. It is fair to question whether average citizens are up to the challenge of making highly technical policy and legislative judgments. But the Irish and other European cases offer encouragement that sortition can, at a minimum, provide sound guidance on issues of national interest. And it provides elected politicians with political cover for issues they consider too sensitive to handle, like marriage equality, sufficiency measures, and even growth.

In any case, societies could adapt and test sortition at progressively greater levels of responsibility. Sortition proponents identify at least eight potential contributions that sortition can make to the political process, including providing advice, as in the European cases. Governments could also use the tool to create watchdog groups that provide ethical oversight of the legislative process. Or they might apply the watchdog function to the executive branch to ensure that bureaucratic rules are faithful to the original intent of legislation.

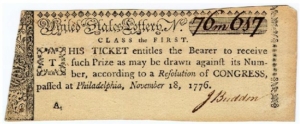

An early lottery ticket. What if the prize were a seat in Congress? (Ephemeral Society of America)

We might imagine other ways to deploy the power of random chance to better reflect the popular will. For example, it might help to build common ground among legislators. Suppose all conservative legislators were required to spend a three-month internship at a soup kitchen or social service agency. And imagine progressives interning in a small business. A lottery system could determine assignments. Wouldn’t legislators emerge with a more broadly shared knowledge base for discussion and debate during their terms?

Or suppose positions of power were rotated among leaders. This could be similar to the rotation of the presidency of the Council of the European Union, but with a twist of randomness. Imagine the UN Security Council being enlarged to 15 members from the current five, with members chosen by lot every few years. Would broader representation yield more decisive resolutions on the mega-crises of our day?

Seeking the Greater Good

The notion that chance could be a constructive addition to governance architecture may seem far-fetched. But a former state senator from California, Loni Hancock, once captured sortition’s inherent appeal. “The idea of a lottery is at first thought absurd, and at second thought obvious.” Sortition seems to tickle the same ethical muscle as Mom’s “one cuts, the other chooses” ruling. It also evokes the “Do unto others” guidance broadly embraced by the world’s major faiths. Something in humans recognizes and longs for basic fairness.

To be sure, creating the veil of ignorance through sortition requires extensive thought and testing. But the experience with sortition in Europe to date is enticing. Sortition can deliver sound advice to elected officials. It might also go further and yield a truly representative set of legislators, an end to the influence of special interests in lawmaker selection, and an expanded space for expression of the common good. All of which could jumpstart action on the megacrises of our time.

How about it: Shall we leave the establishment of a steady state economy to the pro-growth “representative” democracies? Or should we sort it out ourselves?

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

The post Sortition for a Steady State Economy? appeared first on Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy.

The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access – review

In The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access, David Gissen contends that the focus on access in design around disability perpetuates inequalities, arguing instead for centralising disabled people in architectural and urban planning. Amy Batley finds that the book’s attempts to reframe disability in contemporary urban landscapes are overpowered by historical tangents and subjective claims.

While the gendered and racialised inequalities of urban design have become prominent avenues of academic debate, the limited consideration of the needs of disabled people within planning for the public sphere continues to undermine calls for more egalitarian urban design. In The Architecture of Disability, David Gissen pursues this matter, arguing that the overwhelming focus on access when designing cities continues to perpetuate inequalities for people with disabilities in using urban spaces, landscapes and buildings. For Gissen, the architectural emphasis on access is insufficient. In response to this, he calls for a more critical understanding of how disability is experienced in the urban realm, and for those with disabilities to be centralised in architectural and urban design, rather than exteriorised.

While the gendered and racialised inequalities of urban design have become prominent avenues of academic debate, the limited consideration of the needs of disabled people within planning for the public sphere continues to undermine calls for more egalitarian urban design. In The Architecture of Disability, David Gissen pursues this matter, arguing that the overwhelming focus on access when designing cities continues to perpetuate inequalities for people with disabilities in using urban spaces, landscapes and buildings. For Gissen, the architectural emphasis on access is insufficient. In response to this, he calls for a more critical understanding of how disability is experienced in the urban realm, and for those with disabilities to be centralised in architectural and urban design, rather than exteriorised.

For Gissen, the existing architectural emphasis on creating urban spaces which are accessible for those with disabilities is “an incomplete response” which serves to “reinforce entrenched definitions of disability” (ix) by “view[ing] impairments as physical and mental aberrations and burdens to overcome” (xv). Rather than interpreting disability as an aberration for which compensations need to be made, Gissen calls for the creation of an architecture which coexists with disability.

Rather than interpreting disability as an aberration for which compensations need to be made, Gissen calls for the creation of an architecture which coexists with disability.

Gissen’s historical analysis is extensive and detailed, centralising historical examples of urban engagement with disability within the text. The author draws parallels between seemingly disparate historical examples, such as Athens’ Acropolis and Saint Denis’ Basilica, to argue that, in their current form, any reference to historical disability assistance at these two monuments has been minimised. For example, Gissen cites archaeological research which showed that, in Ancient Greece, the Acropolis featured ramps and the area was used by the elderly using canes and crutches. Gissen uses this second-hand historical context to claim that in the case of this monument, the space “might have been more relatable to its impaired visitors in the past than it is in its present-day condition” (9). This historical analysis is similarly strong in a later chapter, where Gissen’s discussion of 19th-century urbanism in Paris presents a refreshing read beyond the dominant urbanist tendency to blame many of contemporary Paris’ successes and ills on Baron Haussmann’s overhaul of the city’ urban planning.

Gissen cites archaeological research which showed that, in Ancient Greece, the Acropolis featured ramps and the area was used by the elderly using canes and crutches

Gissen also provides an additional new perspective from which to consider monumentality beyond existing urban analyses of their political manipulation for nation-building purposes. The author argues that present-day efforts to preserve the historic reference to the vulnerabilities of previous users at monumental sites exposes how contemporary monument management has “sublimated weakness and vulnerability as cultural values” (11) towards an idealised vision of the nation.

Though providing the reader with new perspectives from which to consider the role of disability in contemporary urban landscapes, the book’s central premise – of moving the consideration of disability in the city beyond questions of access – frequently becomes lost amid historical tangents whose relevance to the argument is not always made explicit. For example, Gissen continues his critique of monumentality in contemporary cities, but rather than tying the matter of monumentality to disability, Gissen loses focus and begins to question the role of Confederate and colonial monuments in the context of Black Lives Matter protests. The calls from those protestors deserve thorough consideration and academic debate, but the relevance to a discussion about the architecture of disability is not clarified. This reflects a broader structural problem with the book. Though the architectural and urban connections are intermittently addressed throughout the chapters, these relationships are not always clear, which leaves the reader to try to connect the dots.

Though the architectural and urban connections are intermittently addressed throughout the chapters, these relationships are not always clear, which leaves the reader to try to connect the dots.

Several of the book’s claims will likely frustrate fellow urbanists. This largely stems from the minimal referencing and portrayal of subjective statements as objective facts. For example, in discussing how the rationalisation of European and American cities has made them “some of the most inaccessible places” (53), Gissen takes issue with how the apparent “immensity and exposed quality of the boulevard make walking intimidating” (ibid.). Here, Giddens’ lack of reference to Haussmann’s renovations of Paris, which had been undertaken to enable better vision and military access to quash revolutionary fervour in the 18th-century city, seems to deliberately obfuscate a widely accepted understanding among urbanists. Gidden’s claim that boulevards are intimidating directly contradicts the general urban consensus that, in the right conditions, the surveillance – so-called “eyes on the street”– enabled by urban exposure can create feelings of security and, thus, implies a poor engagement with broader urban theory. Moreover, this argument that open urban spaces can intimidate and deter users is presented at a time when the architectural opening of urban spaces for security purposes has become preferable to hard-engineering measures and the militarisation of urban landscapes, which suggests that the author is choosing not to engage with some of the emerging urban challenges to which his thesis relates.

The book’s aspirations are admirable, presenting a much-needed consideration of the role of disability in contemporary cities. Unfortunately, the book’s historical tangents obscure its central argument while also revealing the author’s nostalgic vision for an urban life more reminiscent of Ancient Greece than one which can engage with the myriad of contemporary challenges faced by disabled people moving through and making lives in cities.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image: XArtProduction on Shutterstock.