Boris Johnson

Abby Innes introduces Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail

In an excerpt from the introduction to her new book, Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail, Associate Professor of Political Economy at LSE’s European Institute Abby Innes considers how factors including the rise of neoliberalism have destabilised Britain’s governing institutions.

Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail. Abby Innes. Cambridge University Press. 2023.

Why has Great Britain, historically one of the strongest democracies in the world, become so unstable? What changed? This book demonstrates that a major part of the answer lies in the transformation of its state. It shows how Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions. This history has direct parallels not just in the United States but across all the advanced capitalist economies that adopted neoliberal reforms. The shattering of the British state over the last forty years was driven by the idea that markets are always more efficient than the state: the private sector morally and functionally superior to the public sector. But as this book shows, this claim was ill-founded, based as it was on the most abstract materialist utopia of the twentieth century. The neoliberal revolution in Great Britain and Northern Ireland – the United Kingdom – has failed accordingly, and we are living with the systemic consequences of that failure.

Why has Great Britain, historically one of the strongest democracies in the world, become so unstable? What changed? This book demonstrates that a major part of the answer lies in the transformation of its state. It shows how Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions. This history has direct parallels not just in the United States but across all the advanced capitalist economies that adopted neoliberal reforms. The shattering of the British state over the last forty years was driven by the idea that markets are always more efficient than the state: the private sector morally and functionally superior to the public sector. But as this book shows, this claim was ill-founded, based as it was on the most abstract materialist utopia of the twentieth century. The neoliberal revolution in Great Britain and Northern Ireland – the United Kingdom – has failed accordingly, and we are living with the systemic consequences of that failure.

Britain championed radical economic liberalisation only to weaken and ultimately break its own governing institutions.

The rise of nationalist populism in some of the world’s richest countries has brought forward many urgent analyses of contemporary capitalism. What this book offers, by contrast, is the explanation of a dark historical joke. It explores for the first time how the Leninist and neoliberal revolutions fail for many of the same reasons. Leninism and neoliberalism may have been utterly opposed in their political values, but when we grasp the kinship between their forms of economic argument and their practical strategies for government, we may better understand the causes of state failure in both systems, as well as their calamitous results.

Comparing the neoclassical and Soviet economic utopias, [w]hat emerges are mirror images – two visions of a perfectly efficient economy and an essentially stateless future.

Britain’s neoliberal policies have their roots in neoclassical economics, and Part I begins by comparing the neoclassical and Soviet economic utopias. What emerges are mirror images – two visions of a perfectly efficient economy and an essentially stateless future. These affinities are rooted in their common dependence on a machine model of the political economy and hence, by necessity, the shared adoption of a hyper-rational conception of human motivation: a perfect utilitarian rationality versus a perfect social rationality. As the later policy chapters demonstrate, these theoretical similarities produce real institutional effects: a clear institutional isomorphism between neoliberal systems of government and Soviet central planning.

When it comes to the mechanics of government, both systems justify a near identical methodology of quantification, forecasting, target setting and output-planning, albeit administrative and service output-planning in the neoliberal case and economy-wide outputs in the Soviet. Since the world in practice is dynamic and synergistic, however, it follows that the state’s increasing reliance on methods that presume rational calculation within an unvarying underlying universal order can only lead to a continuous misfit between governmental theory and reality. These techniques will tend to fail around any task characterised by uncertainty, intricacy, interdependence and evolution, which are precisely the qualities of most of the tasks uploaded to the modern democratic state.

In neoliberalism, the state has been more gradually stripped of its capacity for economic government

The Soviet and neoliberal conceptions of the political economy as a mechanism ruled by predetermined laws of economic behaviour were used to promote pure systems of economic coordination, be that by the state or the market. Leninism, as it evolved into Stalinist command planning, dictated the near-complete subordination of markets to the central plan. In neoliberalism, the state has been more gradually stripped of its capacity for economic government and, over time, for prudential, strategic action, as its offices, authority and revenues are subordinated to market-like mechanisms. Both Soviet and neoliberal political elites proved wildly over-optimistic about the integrity of their doctrines, even as they demonised the alternatives.

For all their political antipathy, what binds Leninists and neoliberals together is their shared fantasy of an infallible ‘governing science’ – of scientific management writ large. The result is that Britain has reproduced Soviet governmental failures, only now in capitalist form. When we understand the isomorphism between Soviet and neoliberal statecraft, we can see more clearly why their states share pathologies that span from administrative rigidity to rising costs, from rent-seeking enterprises to corporate state capture, from their flawed analytical monocultures to the demoralisation of the state’s personnel and, ultimately, a crisis in the legitimacy of the governing system itself. This time around, however, the crisis is of liberal democracy.

The book’s policy chapters in Part II explore how the neoliberal revolution has transformed the British state’s core functions in the political economy: in administration, welfare, tax and regulation and the management of future public risk.

After setting out the philosophical foundations of these ideologies, the book’s policy chapters in Part II explore how the neoliberal revolution has transformed the British state’s core functions in the political economy: in administration, welfare, tax and regulation and the management of future public risk. In Part III I examine the political consequences of these changes, and demonstrate how Britain’s exit from the European Union has played out as an institutionally fatal confrontation between economic libertarianism and reality. The final chapter considers how the neoliberal revolution, like its Leninist counterpart, has failed within the terms by which it was justified and instead induced a profound crisis not only of political and economic development but also of political culture.

Under ‘late’ neoliberalism we can see a similar moment of political hiatus, as neoliberal governments likewise resort to nationalism and the politics of cultural reaction to forestall public disillusionment and a shift in paradigm.

I use different periods of Soviet history as an analytical benchmark throughout the book, but the Brezhnev years (1964–1982) were those of the fullest systemic entropy: the period of ossification, self-dealing and directionless political churn. Under ‘late’ neoliberalism we can see a similar moment of political hiatus, as neoliberal governments likewise resort to nationalism and the politics of cultural reaction to forestall public disillusionment and a shift in paradigm. I use the United Kingdom as the case study because it was both a pioneer of these reforms and, in many respects, has gone furthest with them. If neoliberalism as a doctrine had been analytically well-founded, it was in the United Kingdom, with its comparatively long and strong liberal traditions, that we should have seen its most positive outcomes.

By the early 2020s the Conservative government of Boris Johnson had sought to criminalise peaceful protest, to constrain media independence and to insulate the political executive from parliamentary and public scrutiny.

To be clear, Britain’s neoliberals were never totalitarians of the Soviet variety. They never used revolutionary violence to create a one-party state, deployed ubiquitous intelligence agencies to enforce repression or used systems of mass incarceration and murder for political ends. Britain’s neoliberal consensus has nevertheless favoured a one-doctrine state, and the violent suppression of specific, typically economy-related, protests has been a periodic feature of its politics since 1979. Britain’s neoliberal governments have also developed an increasingly callous attitude to social hardship and suffering. Most troubling of all is that the more neoliberalism has been implemented, the more the country has been driven to the end of its democratic road. By the early 2020s the Conservative government of Boris Johnson had sought to criminalise peaceful protest, to constrain media independence and to insulate the political executive from parliamentary and public scrutiny. In short, it had abused its authority to disable legitimate political opposition. What I hope to explain is why any regime that commits itself to neoliberal economics must travel in this direction or abandon this ideology.

What follows is an argument about the collapse of the empiricist political centre and its replacement by utopian radicalism. Specifically, this is a story of how the pioneering and socially progressive philosophy of liberalism is being discredited by utopian economics and the practically clientelist methods of government that follow from it, just as the politics of social solidarity essential to a civilised world was undermined by the violence and corruption of the Soviet experiment. As the old Soviet joke had it, ‘Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. Communism is its exact opposite.’ There are, of course, many challenges distinct to neoliberalism and I pay attention to them, but my purpose here is to see what we can learn about the political economy of the neoliberal state when we look at it through the lens of comparative materialist utopias.

Note: This excerpt from the introduction to Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail by Abby Innes is copyrighted to Cambridge University Press and the author, and is reproduced here with their permission.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: globetrotters on Shutterstock.

When populism fails

At the Battle of Ideas last Saturday, a panel on "populism" spent an hour and a half discussing everything except economics. Sherelle Jacobs of the Telegraph called for the Tory party to replace what she called a "twisted morality of sacrifice and dependency" with the "Judaeo-Christian" values of thrift and personal responsibility. And when a brave audience member asked "shouldn't we be discussing economics?" Tom Slater of Spiked brushed him off and carried on talking about cultural issues. Economics be damned, populism is all about morality and culture.

But important though morality and culture are, it is economics that really matters. Rudiger Dornbusch's work on macroeconomic populism shows that populism eventually fails because the economics don't work. And when it does, the people who suffer most are those the populists intended to help.

In this study (pdf), Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards define macroeconomic populism thus:

Macroeconomic populism is an approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income distribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies.

Liz Truss's disastrous budget meets this definition. It was explicitly intended to stimulate growth, and she and Kwarteng ignored the risks of inflation and deficit finance, wrongly assuming that external investors and domestic voters would approve of the plans. Furthermore, the package as a whole was aggressively redistributive, cutting taxes predominately for the rich and supporting household incomes right across the income distribution.

But although macroeconomic populism failed on Truss's watch, she was neither its source nor its principal architect. The principal architect was Boris Johnson. And the source was George Osborne.

Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards locate the source of populism in austerity. "The populist paradigm is typically a reaction against a monetarist experience," they say. And they go on to explain how economic stagnation results from austerity:

Initial Conditions. The country has experienced slow growth,

stagnation or outright depression as a result of previous stabilization

attempts. The experience, typically under an IMF program, has reduced

growth and living standards. Serious economic inequality provides

economic and political appeal for a radically different economic program.

The receding stabilization will have improved the budget and the external

balance sufficiently to provide the room for, though perhaps not the

wisdom of, a highly expansionary program.

This well describes the UK of the early 2010s. The economy was stagnant, growth was slow and living standards were poor. And although the UK was not subject to an IMF programme, other countries in Europe were. George Osborne and David Cameron leveraged fear of becoming "like Greece" to convince a long-suffering population that austerity now was necessary to ensure growth and prosperity returned in the future.

But by 2015, growth and prosperity had not returned. Rising inequality and poor living standards, particularly outside London and away from big cities, fuelled popular anger. With rebellion against austerity in the air, Osborne engineered something of a housing boom in time for the 2015 election and succeeded in winning an outright majority for the Conservative party. Just over a year later, both Osborne and Cameron were out of office. But the Conservative party wasn't.

The turn to populism often starts with the election of a left-wing government. But in the case of the U.K., it didn't. It started with the campaign to leave the EU. Brexit is a populist movement, but not a socialist one. Many of its proponents want free markets and a small state, and while others want a bigger role for the state, they see it as fostering enterprise in left-behind regions. "Take back control", cried the Leave campaign. "WE WILL!" shouted back the voters in the 2016 referendum. The following day, Cameron resigned. His replacement, Theresa May, sacked Osborne.

May continued to make deficit-reducing spending cuts throughout her premiership. In 2018 she promised to end austerity "when Brexit was done". But within a year she too was out of office, replaced by Boris Johnson, a leading light of the Brexit movement. In December 2019, the Conservative party won a landslide victory on Johnson's promises to "get Brexit done" and "level up" the country. And so it came to pass that the same centre-right political party that had inflicted the austerity of the post-crisis years, rejected it.

Johnson told voters that austerity was over, and promised large-scale investment in infrastructure and public services. Suddenly, the government deficit and debt, on which attention had previously been lavished to the point of fetishism, was no longer important. The government had sufficient fiscal room to do whatever it wanted. And when the Covid pandemic hit, all constraints on government spending were removed. The UK had pivoted fully from austerity to Dornbusch's "no constraints":

No Constraints: Policy makers explicitly reject the

conservative paradigm. Idle capacity is seen as providing the leeway for

expansion. Existing reserves and the ability to ration foreign exchange

provide room for expansion without the risk of running into external

constraints. The risks of deficit finance emphasized in traditional

thinking are portrayed as exaggerated or altogether unfounded. Expansion

is not inflationary (if there is no devaluation), because spare capacity

and decreasing long run costs contain cost pressures and; there is room to

squeeze profit margins by price controls.

To be sure, the UK was far from alone in removing all constraints at this time. Governments all over the world were spending without limit, supported by massive QE from their central banks. But Johnson's agenda was far more than just a pragmatic response to a public health crisis. It was a radical populist programme:

The Policy Prescription. Populist programs emphasize three

elements: reactivation, redistribution of income and restructuring of the

economy. The common thread here is "reactivation with redistribution". The

recommended policy is a redistribution of income, typically by large real

wage increases.

Johnson's rejection of his predecessors' austerity was accompanied by an explicit commitment to redistribution and restructuring not only of the UK economy, but of society. The "levelling up" agenda that bought him the votes of the "red wall" aimed to close the wide income and wealth gap between London & the South East and the rest of the UK.

Johnson's profligacy led to carelessness and corruption, both financial and personal. Eventually, it brought about his downfall. But Truss inherited his mandate, and although her first action on coming into office was to downplay "levelling up" in favour of an equally radical "growing the pie", her plan for tax-light "enterprise zones" across the country was, at least in theory, strongly redistributive. Her mini-budget was every bit as populist as Johnson's programme. But not more so. Had he remained in office, Johnson's populist programme would eventually have unravelled as disastrously as hers - because populist programmes always do.

Dornbusch and Edwards document four phases in the collapse of macroeconomic populism, which I reproduce verbatim below. Their work is on Latin American countries, so not entirely applicable to the UK. But the lessons nonetheless are valuable.

- Phase I: In the first phase, the policy makers are fully

vindicated in their diagnosis and prescription: growth of output, real

wages and employment are high, and the macroeconomic policies are nothing

short of successful. Controls assure that inflation is not a problem, and

shortages are alleviated by imports. The run-down of inventories and the

availability of imports (financed by reserve decumulation or suspension of

external payments) accommodates the demand expansion with little impact on

inflation. - Phase II: The economy runs into bottlenecks, partly as a

result of a strong expansion in demand for domestic goods, and partly

because of a growing lack of foreign exchange. Whereas inventory

decumulation was an essential feature of the first phase, the low levels

of inventories and inventory building are now a source of problems. Price realignments and devaluation, exchange control, or protection become

necessary. Inflation increases significantly, but wages keep up. The

budget deficit worsens tremendously as a result of pervasive subsidies on

wage goods and foreign exchange. - Phase III: Pervasive shortages, extreme acceleration of

inflation, and an obvious foreign exchange gap lead to capital flight and

demonetization of the economy. The budget deficit deteriorates violently

because of a steep decline in tax collection and increasing subsidy costs.

The government attempts to stabilize by cutting subsidies and by a real

depreciation. Real wages fall massively, and politics become unstable. It

becomes clear that the government has lost. - Phase IV: Orthodox stabilization takes over under a new

government. An IMF program will be enacted; and, when everything is said

and done, the real wage will have declined massively, to a level

significantly lower than when the whole episode began! Moreover, that

decline will be very persistent, because the politics and economics of the

experience will have depressed investment and promoted capital flight. The

extremity of real wage declines is due to a simple fact: capital is mobile

across borders, but labor is not.

The extraordinary conditions of the pandemic complicate things somewhat. But looking back, it can be said that the macroeconomic policies of the pandemic were successful, and their enormous expense was not a problem because the central bank was - unusually for the UK - captive at that time. I find it odd that those complaining about the threat of fiscal dominance in the Bank of England's handling of the gilts meltdown under Truss have failed to notice two whole years of actual fiscal dominance under Johnson. The Bank of England explicitly ensured that Johnson's government could finance exorbitant expenditure on covid-related schemes. I am not saying that this was a mistake: there was a clear need for coordinated government and central bank action to keep people and businesses alive during successive lockdowns. But we should beware of double standards. Johnson's extraordinary profligacy was supported by the Bank of England and accepted by markets. Truss's was not.

So the pandemic period was Phase 1, when the populist paradigm works brilliantly. And thank goodness for it. Attempting to do austerity at that time would have been disastrous.

The cracks started to appear as the economy reopened. Supply chain problems caused shortages and price rises. Inflation started to rise. This was Phase 2.

Political instability and the Ukraine war ushered in Phase 3. Energy prices spiked and inflation shot up. Johnson was ousted by his own MPs, and there was then a protracted leadership campaign, during which the eventual winner, Liz Truss, said some worrying things and made some unwise promises. By the time she took office, gilt yields were already rising and sterling experiencing considerable volatility. But the wheels came off with the "mini-budget" on September 23rd.

Quite why Truss thought she could introduce a wildly profligate budget when inflation was high and rising, interest rates rising and sterling already under pressure is unclear. Perhaps she genuinely thought she would be able to face down financial markets. After all, her government wasn't socialist, it was a right-wing, true-blue Tory government with an agenda modelled on the successful tax-cutting programmes of Thatcher and Reagan. Surely financial markets would approve?

But financial markets are amoral. They don't care whether a government favours the rich or the poor. They only care that its economics make sense. Truss's didn't. So they punished her in exactly the same way that they would a socialist government pursuing a massive programme of unfunded welfare increases at a time of rising inflation, binding resource constraints and near-full employment. They sold everything denominated in sterling, including sterling itself. Capital fled from the UK.

Dornbusch doesn't mention the importance of personalities, but in my view part of Truss's problem is that she isn't Johnson. She is, if you like, the UK's equivalent of Nicolas Maduro, the Venezuealan leader who took over from Hugo Chavez but has never commanded his popularity. Truss has neither Johnson's popular appeal nor his communication skills. Johnson might have been able to blag his way through the return of the bond vigilantes, but Truss, wooden and unempathic, never stood a chance.

Now, the UK is in phase 4. The Conservatives have appointed a new Chancellor who has already taken a hatchet to Truss's tax-cutting budget and is indicating further cuts to come. And with her entire economic programme now in shreds on the floor, Truss seems unlikely to be able to hold on to office for much longer. It is not at all clear who will replace her, and the prospect of the Conservatives putting in place an unelected technocratic government with no mandate to undertake the fiscal consolidation that is now necessary is profoundly undemocratic. We need a General Election, not a Tory coronation.

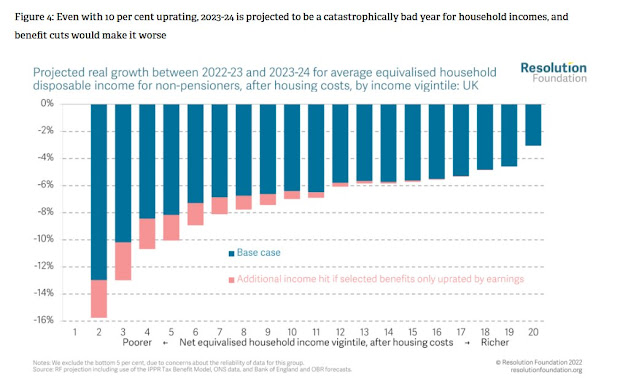

We have come full circle. Austerity is back, bigger than before. And those who will pay are the very people that voted for Johnson and for Brexit because they thought this would make their lives better. Just as Dornbusch and Edwards predicted, there will now be brutal real income falls across the entire income distribution. This chart from the Resolution Foundation is unbelievably stark:

Nor are pensioners likely to escape the income squeeze. The Chancellor has already indicated that he may take his hatchet to the sacred triple lock that ensures their state pensions always rise by as much or more than inflation and average earnings. And the returns on their savings are unlikely to keep up with inflation.

Why do populist programmes always end disastrously for those they aim to help? It's not because of lack of commitment, or failure to make the case for them. Populist leaders often believe strongly in their programmes. It is the economic substance of the programmes that is the problem. Populist politicians think the rules of economics don't apply to them. They eventually find out the hard way that they do.

Truss's attempt at a Barber-style "dash for growth" was short-lived, but its consequences will be long-lasting. The UK now faces persistently raised interest rates, a persistently weaker currency, and persistently higher government borrowing costs as a direct result of her folly.

Sadly, as Dornbusch and Edwards warn, the return of austerity, if not tempered by measures to improve growth and what they call "social progress", will sow the seeds of the next crisis. And this is where those who see populism as being about morality and culture perhaps have something important to contribute. For it is morality, not economics, that says the social fabric of society is important and must be maintained.

Osborne's economics-driven austerity shredded social safety nets and rendered essential public services unfit for purpose. It is vital that the new technocratic government does not embark on the same disastrous course. We don't need a "new morality", we need to reinforce our traditional British - indeed, dare I say it, Judaeo-Christian - values of fairness, duty, compassion and generosity.

Related reading:

Austerity and the rise of populism

The social imprint of sovereign defaults, CEPR

Image:A 2012 rally by members of the left-wing populist United Socialist Party of Venezuela in Maracaibo. By Wilfredor - Own work, CC0, Wikipedia

A C Grayling on rejoining the EU: a rational case in a time of unreason?

A C Grayling addressing Bath for Europe, Widcombe Social Centre, Bath, 18th February 2020

A C Grayling addressing Bath for Europe, Widcombe Social Centre, Bath, 18th February 2020

I spent yesterday evening listening to a speech by the philosopher A C Grayling at a meeting in Bath, organised by Bath for Europe, on the subject of rejoining the EU (unfortunately I had to leave before the Q and A in order to stand a fighting chance of getting a train back to Cardiff). Grayling has been one of the heroes of the Remain movement: acerbic and indefatigable. I went along to this because, as in the aftermath of December’s disastrous election result, Remainers have to think about what to do next. In particular, we need to decide whether to campaign all-out to rejoin – in the knowledge that Johnson and Cummings appear to be determined to move us as far as possible away from any meaningful relationship with the Union, making rejoining increasingly difficult as time goes on – or whether now is not the time, following the body-blow of that election result.

Grayling argued that the UK could be back in the EU in no more than a few years. His scenario – which he freely admitted was optimistic – revolved around:

– an acceptance that the majority of people had voted for remain or pro-referendum parties, and it was a divided opposition that had allowed Johnson to win and gain the untrammelled power that a Parliamentary majority confers in our political system;

– that in order to overturn the grave harm that Brexit did to the UK, parties of the left and centre-left needed to make common cause, and to offer an electoral pact at the next General Election in support of both electoral reform and a new referendum. That election could come in less than five years if Johnson (and Cummings) managed to throw off the shackles of the Fixed Term Parliament Act and revert to the tactic of holding elections at a time of the Government’s choosing;

– the reality of the negotiations was that they could not be concluded by the end of this year and that politicians would shy away from the appalling political consequences of a no-deal Brexit;

– the EU wants us back, and if the UK remains closely aligned to the EU and its rules the acquis – the conditions of membership – should be relatively easy to meet.

It’s an attractive – some would say idealistic – scenario; Grayling concluded that politicians were wrong to shy away from campaigning to rejoin. We needed to set the campaign going on the ground now, possibly through the use of People’s Assemblies.

Afterwards, I reflected that Grayling’s approach was reasonable, logical and closely-argued. And therein, in a time of unreason, lay its problems.

First, I was worried by his analysis of the result of the General Election. Yes, he is absolutely right about the aggregated UK figures; Johnson did win with the backing of a minority of the electorate and there was a small majority in favour of remain-leaning parties. But once one disaggregates the result the situation changes. Johnson’s triumph was overwhelming in England; and since his election has shown himself to be an unrepentant English nationalist. Scotland looks set for another referendum and possible departure from the UK; Northern Ireland’s position looks set to change as a result of Johnson’s unworkable border proposals and there is an upsurge in interest in independence in Wales; with elections in all three nations next year. Johnson talks a lot about the Union, but not at all about the democratic aspirations of the non-English nations, which will be undermined by Brexit. I think one could argue that the Tory election win was down to an upsurge in English nationalism and the ability of a Tory Party that has changed beyond recognition in recent years to capture nationalist sentiment. There appears to be a new, nationalist, pro-Brexit electoral coalition in England that Johnson will want to appease, and if that means throwing the troublesome Scots and Welsh under the proverbial bus, so be it. The effect of Brexit could be to accelerate the break-up of the Union, with parts – Scotland, Northern Ireland, and even Wales – rejoining. Whatever happens, that Union seems likely to change irrevocably.

Second, it is difficult to see how a coalition of opposition parties could be pulled together. Grayling said that he had rejoined Labour to vote for Keir Starmer in the leadership election; but whatever the outcome of that election there is no appetite in the Labour Party to reopen the Brexit debate that has traumatised it under Jeremy Corbyn’s hapless leadership. And there is likely to be even less appetite for any sort of rapprochement with the Liberal Democrats; Labour’s anti-Lib Dem venom is as powerful as ever.

But most of all, Grayling is advocating reasonable behaviour in a time of unreason; and I wonder whether as a polity the UK is ready to re-embrace that reason. On a (much-delayed) journey home across the border to Wales, I kept reflecting on a comment made by a staffer in the George W Bush administration, often attributed to Karl Rove:

The aide said that guys like me were ‘in what we call the reality-based community,’ which he defined as people who ‘believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.’ […] ‘That’s not the way the world really works anymore,’ he continued. ‘We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do’

I think it’s a quotation that’s relevant to our times: a very Cummings-eque description of what liberals and democrats – people who adhere to the values set out in Article 2 of the Lisbon Treaty – are up against when facing a wholly unscrupulous politics based in populism, nationalism and the denigration of truth in favour of heroic ideological statements. And because of that, I question whether we are yet ready to begin that campaign to take us back to where we belong in Europe. Because it seems to me that unless and until we can reassert a politics based on reason and truth, any campaign to rejoin could strengthen the hand of the populists and nationalists.

I respect A C Grayling for the passion, the logic and the clarity with which he set out his case. He was well-received by an audience that was clearly drawn from the reality-based community. But it seems to me that there is a bigger political battle to be won before we can lance the boil of Brexit, one that depends on the ability of liberals to rebuild the case for liberal democracy itself.

It’s our money: HS2, the Barnett formula, and the threat to Welsh democracy

Yesterday’s announcement from Whitehall that HS2 would proceed – at an estimated cost now of £100bn, a figure that seems likely to rise substantially – has opened a wide fault-line about the future of Wales and Welsh devolution.

As Plaid Cymru MP Jonathan Edwards argues persuasively in a piece in Nation Cymru, the issues for Wales are simple. HS2 is classified as a project that benefits both England and Wales, and therefore Wales will not receive any consequential funding as a result of the Barnett Formula, which provides that increasing public expenditure in England will be reflected in an increase in Westminster funding for Wales. This is despite the fact that not a centimetre of HS2 track will be laid in Wales and economists estimate that HS2 will actually damage the economy of South Wales – to the tune of £150m per year; the justification is that it will be possible to get a connecting service from Wrexham to Crewe, which some would regard as a pretty desperate piece of post-hoc rationalisation. It looks especially threadbare when one considers that Scotland – which will potentially benefit from substantially reduced travel times to London – will receive Barnett consequentials.

The loss in Barnett consequentials is likely to be around £5bn – assuming the £100bn overall cost of HS2 is correct (and it seems reasonable to expect it will come in above that).

All of this matters, not just because of the loss of £5bn of desperately needed funding in the poorest country in Northern Europe, whose economy is blighted by notoriously inadequate transport links. It throws into sharp relief issues that are beginning to emerge about the future of devolution itself.

First, it is a reminder that the Barnett Formula is no more than a convention. It has no force in law, and only exists as long as the Treasury in London allows it to exist. The Treasury could announce tomorrow that it was over and the Welsh Government could do absolutely nothing about it.

And politically, it’s essential to remember two things: first, that the new Tory government, faced with the austerity that will inevitably follow the hard Brexit it now appears to be pursuing, will be under huge pressure from its new North of England Tory MPs to protect spending in their areas, in line with Boris Johnson’s rhetoric about promoting the North of England. The convention that automatically uplifts Wales’ spending settlement is bound to be under political pressure in these circumstances.

Morevover, Wales has recently been granted tax-raising powers. There is a close fit with the Cameron governments’ localism agenda, which in theory granted extra revenue-raising powers to English local authorities through retention of business rates, but in practice became a rationale for cutting central Government funding: the message was, you can raise the money locally so we don’t need to fund you.

So there is a clear rationale emerging in which Welsh political institutions continue to take the responsibility for providing services but are systematically starved of the resources to do so; the scenario facing many English local authorities but from which Wales – has to a limited extent – been protected by the Barnett formula (although it’s becoming increasingly obvious that the ability of Welsh political institutions to deliver services like health is under huge and growing pressure).

And, second, it’s essential to understand the political context in which the HS2 decisions have been taken. It was instructive to hear Boris Johnson, yet again, using the HS2 announcement to attack the Welsh Government’s decision not to build the M4 relief road around Newport. The point is that whatever one might think of that decision, it was taken in Wales by our own government; Johnson and Westminster have absolutely no jurisdiction. here.

Added to that is the huge pressure that Brexit – especially the hard Brexit envisaged by Whitehall – will place on Wales: both on our economy and on our political autonomy. The effect of a hard Brexit will obviously be catastrophic for Wales; the Government’s own estimates suggest a 7% fall in GDP across the UK as a whole – similar to what Spain and Ireland experienced in the Eurozone crisis. Wales, because of our economic structures, is far more vulnerable than many parts of the UK. And the EU withdrawal legislation means that over areas determined by Whitehall fiat to be part of the UK single market, it will be far more difficult for the Welsh Government to act, least of all to mitigate the effects of Brexit on either the economy or essential quality-of-life issues like the environment or food standards.

In other words, the HS2 decision is a reminder that the cumulative effect of Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party’s attitude towards Wales – including its attitude to Brexit – is to undermine fatally both our political institutions and our ability to finance our own public services; it is essentially a denial of service attack on Welsh democracy. And anybody on the progressive side of Welsh politics has to understand that the HS2 decision exposes clearly the ruthless determination of Tories, ultimately, to ensure that Wales learns its place and takes its medicine.

So where do progressives start to fight back? One of the complaints that one hears on the progressive side of politics is that we don’t have the three-word slogans that Boris Johnson and his minders used so devastatingly in the EU referendum: “take back control” and “get Brexit done”.

So here’s one for Welsh progressives: “its our money”. And let’s use this as a reminder that achieving progressive politics in Wales is intimately bound up with developing constitutional arrangements that are fit for purpose, robust and not subject to Whitehall whim.

We Remainers built a huge mass movement. Where do we go now?

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

For those of us in the movement to remain in the EU, this has been a grim few days. It appears inevitable that we will leave the EU on 31st January – and lose our freedom of movement, so many of our rights as citizens, our jobs and services.

But, along the way, we did something extraordinary. We built one of the biggest mass movements Britain has ever seen – and built it, crucially, from the grass roots up. We twice got well over a million people on to the streets of London; many thousands more on to the streets of our cities, towns and communities; got six million signature on a petition to revoke Article 50 in a matter of hours.

And it was, for the most parts, a genuine grass-roots movement. We came from across all political parties, but, most important of all, so many of our brightest stars, best organisers and most indefatigable activists had never been active in politics before. We had energy, passion, belief and wit (look at some of our banners!). It has been a joyous experience, a celebration of shared values.

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

And we always knew that Brexit was about far more than leaving the EU. It was about values and culture; about whether we wanted to be an open, optimistic society taking our place in the world, or a crabbed, fearful one cringing behind our shutters against the world. It was about liberal values, about the preservation of liberal democracy (not least against the shameful, wholly dishonest politics of the EU referendum and the populist sloganising that followed it). The sharing of values ran deep and wide; this was not a campaign, it was a movement.

Speaking personally, it has been the most exciting political movement I have ever been involved in; and I realise that, working in the cross-party and no-party campaigns here in Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan, the conversations that I, as an ex-Labour Party member, have had with people from across the party spectrum (including ex-Conservatives) have been more open, more constructive, more adult, more intelligent than any I could have had with, say, the cultists of Cardiff Momentum. And not just about Brexit; the sharing of values goes deep.

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

Photograph (c) Neil Schofield-Hughes

Of course there have been sneers – Owen Jones’ infamous comment that one of our marches was the world’s longest Waitrose queue. Well, Owen would know. But what I do know is that in the Labour Party, Corbyn loyalists in particular used to talk a lot about solidarity, about mass movements; but all too often it was a case of a handful of sad old Trots living out their fantasies (and all the time characterising mass movements as a cheerless rank-and-file, characterised by obedience and uniformity and led by the directing force of the vanguard party elite; well, if there’s one thing I know after three years of the anti-Brexit movement, it is that real mass movements are glorious in their diversity, their humour, and occasionally their sheer stroppiness).

So, where now?

After last Thursday, defeating Brexit looks like a lost cause (although we should never write anything off). But the things behind Brexit – the lies, the crude populism, the racism, the contempt for democratic process – are still there. A Johnson majority government will see attacks on public institutions – the NHS above all – but also the undermining of the independence of the judiciary, the continued disgusting treatment of EU citizens in the UK, a policy of outright hostility against immigrants. And these are all questions of values – whether we are prepared to accept a Trump-like “post-truth” populism, or reassert liberal, democratic, constitutional values. And with Labour unable to own its own role in its defeat, and with Corbyn still claiming that Labour “won the arguments”, there seems to be little doubt that Labour will move on from its own internal dialogue. Something more is needed.

How about a genuine movement in defence of liberalism? How about harnessing the energy, the imagination, the passion, the sheer sense of fun of the millions of people who have come together to oppose Brexit, to oppose the things that lie behind Brexit – populism, nationalism, authoritarianism – and to promote liberal, progressive democracy based on values of inclusion, diversity and internationalism?

Because that is the real divide in our politics now. These could be grim years. But hope lies in the spirit that pervaded our glorious grass-roots ant-Brexit movement.

Tactical voting is not enough. To stop Brexit – and save democracy – we need a Coupon Election.

The General Election that will take place on 12th December is the most important in modern British history. It is an election that will decide not just whether the UK leaves the European Union – and hence whether the Brexit project, a project of the far Right that aims to embed austerity, succeds: it is also about whether the United Kingdom survives as an entity and, most importantly, is one that will decide whether Britain takes the road to Trump-style populism (whether of Right or Left) or whether it reasserts its faith in empirical, progressive liberal democracy.

At the heart of decision is the fact that Brexit has become far more than a matter of whether the United Kingdom leaves the European Union. Brexit has become the central issue in a culture war, one in which democracy has been subverted by the insistence that a Brexit that reflects the assumptions and aspirations of the far economic Right – one that destroys jobs and services, that sells the NHS to US health-care providers and big pharma, that destroys environmental and food standards, and removes rights of both UK and other EU citizens to freedom of movement – is “the will of the people”. And that claim institutionalises a referendum – advisory in law and corrupted by malpractice – as a legitimate expression of democracy that stands above the right of Parliament to decide. It is a Brexit that has elevated the outcome of a narrow, corrupted, three-year-old plebiscite into a democratic act in which the choices that have been made by politicians – often out of fear of the extremists in their own parties – into an expression of the popular will. It has led to a situation in which unlawful data manipulation, contempt for Parliamentary and democratic norms, open gerrymandering through controlling electoral registration, and threats of violence against politicians who dare to speak truth to power have become commonplace.

And it is a Brexit in which the leadership of the Labour Party is just as culpable. The evolution of Labour’s Brexit policy makes Finnegan’s Wake look like a model of narrative simplicity, but its confusion and tortuous contradictions are the result of one central fact; its determination to “respect the referendum”. But in order to do that, you have to accept that a marginal result in a corrupt election is something that sets in stone the most important decision of our time; and accepts that Parliament does not have control any more. There are many courageous Labour MPs who have understood that democracy means putting the interests of your constituents first, and that democracy is about far more than obedience to a corrupt plebiscite in order to deliver a Brexit framed by politicians of the Right; but they are the minority.

So, we have a divide that has cut right across the two main political parties in the UK. Other parties have been clearer: the Liberal Democrats, SNP, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party are all Remain parties. However, the Conservative Party has, since the election of Boris Johnson as Leader – and the installation of Dominic Cummings as his ideological minder at No 10 – purged its liberal wing with a ruthlessness and efficiency that the supporters of Jeremy Corbyn – who have presided over a similar attempt to ensure ideological purity in the Labour Party – must envy. Liberal Tory MPs have been expelled or are standing down in their droves; especially women. Meanwhile, the Labour leadership – to the despair of many of its MPs, and of those of its members who have not left already – is largely controlled by people from outside the democratic Labour tradition. As I have argued in my book, they draw their politics from a Leninist model of political organisation in which political direction is given by a vanguard elite, with the only role of the ordinary members ( the “rank and file”) being to give that vanguard democratic legitimacy by voting its decisions through.

The one beacon of hope in all of this has been the willingness of Parliament to seize control. Assisted by the efforts of a courageous Speaker who has been willing to stand up for the rights of Parliament against an executive that has openly agitated against its independence, MPs have taken control of the process. They are the people who have ensured that we are still in the EU, and have stood firm against both the intellectual dishonesty of Brexit and the bullying of a Conservative Party leadership that has no respect for democratic norms.

So, what is to be done?

I think the answer from a Remainer and democratic perspective must be – we need to get past party labels and ensure the election of a Parliament of remainers – which, because of the resonances of Brexit, means a Parliament that is willing to assert the values of empirical liberal democracy. A Popper Parliament, one might say. My own view – for what it is worth – is that Brexit in its broadest sense represents a political convulsion which will see a realignment of party politics; and that at the heart of that realignment will be a reassertion of liberal values against populism. But whether that happens or not, my belief as a democrat is that populism, whether of right and left, must be defeated.

And that means moving the focus away from parties to candidates. As well as considering who is most likely to win in an individual constituency, it’s important to consider what each candidate’s position on Brexit is – and, if they are an MP seeking re-election, looking at their record. There is no point in voting tactically in favour of a former MP who has simply toed Corbyn’s line – which is that Labour should be delivering a better Brexit. Or one who follows the line being sent out from Corbyn’s ideological minders that Labour should be neutral on Brexit; because if you want to preserve the NHS, protect jobs and services, maintain workers’ rights, keep environmental and food standards, and preserve freedom of movement, you simply cannot be “neutral” on Brexit. You are voting for a Labour MP who, in truth, has morally and intellectually capitulated to the Brexiters’ neoliberal agenda.

And, by the same token, that means rewarding Labour MPs who have stood up againt Brexit. To take an example: Cardiff Central is one of the Liberal Democrats’ top targets in Wales, but Labour’s Jo Stevens resigned her front bench post over Brexit, and has been a staunch supporter of the People’s Vote campaign and has been with us front and centre in the campaign against Brexit in Cardiff and Wales more generally. She has earned the vote of every Remainer in that predominantly remain constituency. Likewise, we should back liberal Tories: people like Dominic Grieve, standing as an independent, or Antoinette Sandbach, seeking re-election under Liberal Democrat colours in Eddisbury, deserve the unstinting support of remainers.

And we should not accept simply being content with tactical voting. We Remainers seem unduly reticent about our strength. It was us, not the Brexiters, who twice got more than a million people – protesting loudly but peacefully – on to the streets of London. It was us, not the Brexiters, who managed to get six million signatures on a petition to revoke the UK’s Article 50 notification. Only today, the Brexiters promised a mass rally in Doncaster – nobody, literally nobody turned up: not even the Weimaresque local Labour MP Caroline Flint who has chosen to back the Johnson deal in the hope that it will save her seat. It’s time we in the Remain movement realised that we are powerful, and organised. I can understand that the national remain movement has sought to keep out of party politics; but we in the grassroots need to use our strength and back candidates of whatever party who stand firm against Brexit, stand firm against the leaderships of both Labour and Tories, who want to deliver Brexit.

Above all, we need to convince Labour people to vote for good candidates from other parties – especially Liberal Democrats. Yes, I know what the Liberal Democrats did in 2010; it was appalling and they paid for it politically. But things have moved on; the Orange Bookers have been routed and this election is about the future, not the past. The fact is that any Brexit means you will not be able to deliver your aspirations for a society that is more equal, more just – a society for the many, not the few: even the soft cuddly Brexit that Corbyn (wrongly) thinks the EU will allow him to negotiate. Jeremy Corbyn claims to lead a member-led party, but the Leninists around him have treated you with contempt. They haven’t listened to you, they have dismissed you, they have done everything they can to ensure your beliefs are not reflected in Conference policy, they have reminded you that you need to remember your place in the so-called “rank and file”. It is surely time for you to rediscover your self-respect and vote for what you know is right, not what will get you a pat on the head from your local Momentum enforcer. Your grandchildren are more important; give them an internationalist and democratic future.

And ultimately we need a list. The tactical voting websites appear to have been largely discredited before they have begun. We need to move on from party. We need to be able to say to candidates; it’s your choice. You can have the remainers’ coupon, or you can stand up for your Brexiter party leadership in Westminster. But there are millions of us, and probably our numbers in your constituency are probably enough to seal your fate.

But above all it’s time we stopped being defensive. We need to organise, and at a national level, Remainers should be issuing our coupons. We are counted in our millions and we should use our power. And if we do, we can stop Brexit and defeat populism at the most important election of our time.