Theresa May

Video: protests for Assange as British justice goes on trial in extradition case

Up to 2,000 gather for ‘last chance’ to stop disgraced US case allowed so far by courts – but system seems stacked against Wikileaks founder, press freedom and public’s right to know

Protestors outside the court on Tuesday

Protestors outside the court on Tuesday

Up to two thousand protesters gathered to demonstrate outside the Royal Courts of Justice today in London, where Wikileaks founder Julian Assange and his legal team are fighting in what may be their last chance to avoid his extradition to the US, where the Biden administration wants to lock him in a high-security prison for the rest of his life for the ‘crime’ of exposing the actions of the US military.

Wikileaks embarrassed the US by revealing the wanton slaughter of Iraqi civilians – and the US wants its vengeance. To the UK’s shame, successive UK governments and courts have been all too eager to let the Americans have their way, despite the US case collapsing in disgrace when its main witness to Assange’s supposed ‘hacking’ of US systems admitted he had been lying the whole time – and plots by senior US officials to assassinate him. The admission should have seen the US laughed out of court, but UK judges granted its request anyway.

Protesters massed to show their solidarity with the Australian journalist, who has been imprisoned in Belmarsh prison since 2019 after a long effective incarceration in the Ecuadorian embassy while the UK and US governments conspired against him and even bugged supposedly sacrosanct meetings with his lawyers:

Wikileaks Editor-in-Chief Kristinn Hrafnsson gave the protest crowd a lunchtime update on the ‘absurd’ proceedings, which kept observers down to a handful despite the importance of the case, preventing even human rights groups from attending:

As with all the hearings so far, the case against Julian Assange appears to be stacked. After the farce of the collapsed US case being granted anyway, Assange’s appeal was denied by a judge with deep security service connections.

In the current case, one of the two judges was a lawyer for the Secret Intelligence Service and the Ministry of Defence, with clearance for access to ‘top secret’ information – and the other judge is the twin sister of right-wing former BBC chair Richard Sharpe, who resigned after an inquiry into his arrangement of an £800,000 loan for Boris Johnson before his appointment.

Activist Steve Price, who represented Skwawkbox at the demo, summarised the day:

On a cold day thousands gathered to lobby the court and raise public awareness of this situation. This morning at the RCJ, the chant of the day was “There’s only one decision – no extradition!” The demo was noisy, very colourful, with a visible but low-key police presence and many passing drivers honking horns in solidarity.

Speakers included three Labour MPs – Richard Burgon, Zara Sultana and Apsana Begum, alongside Chris Hedges, Andrew Feinstein, Stella Assange and Julian’s brother and father, as well as lawyers, Reporters without Borders (RwB) and Wikileaks’ editor-in-chief. John Pilger, the great Australian journalist, was remembered with great affection.

Julian’s brother said the Australian Parliament voted by two thirds criticising the UK and USA and demanding he be released and returned to his home country. Two of the lawyers, as well as RwB noted that this case has enormous implications for freedom of the press globally and there are obvious parallels with how journalists have been deliberately targeted by Israel in Gaza.

The magistrate back in January 2021 decided Julian should be released solely on the grounds that he might kill himself, but this was overturned by the Home Secretary. There are a number of legal grounds his team will advocate for refusing the extradition. He has been detained in Belmarsh (in solitary confinement) for nearly 5 years, spent 7 years before that confined in the Ecuadorian Embassy. His health has deteriorated, it’s a form of torture, they’re slowly killing him. He is believed to be too ill to attend court today?

They want to extradite him for the crime of journalism, for exposing their hypocrisy, their dirty secrets, their war crimes.

Keir Starmer, the ‘human rights lawyer’, as he never tires of reminding everyone, has never spoken in Assange’s defence. As Director of Public Prosecutions, his actions are murky – because the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) destroyed its records of them and destroyed notes of what it destroyed. However, it is known that in the case of another extradition the US wanted – that of autistic hacker Gary McKinnon – Starmer flew in a rage to the US to apologise to his US government contacts as soon as then-PM Theresa May quashed the extradition on humanitarian grounds. The CPS and Sweden also destroyed records of their communications when the CPS was pressuring Sweden to continue to pursue Assange’s extradition there – no doubt a stepping stone to getting him to the US – on discredited rape allegations. Despite the destruction of evidence, it is known that the CPS told Swedish counterparts not to ‘dare’ drop its request and refused Sweden’s offer to come and interview Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy.

Assange’s family and team have asked everyone who can make it to the court to continue demonstrating throughout the duration of the hearing to try to keep up pressure on the authorities. The Establishment’s relentless assault on Julian Assange is a war not just against him, but against press freedom and the right of the public to know what its supposed representatives are doing and to hold them to account.

The UK justice system has a last chance to show it is fit for purpose. If it happens, it looks as though justice will have to be wrung out of it. Absolute solidarity with Julian Assange and all persecuted journalists everywhere.

SKWAWKBOX needs your help. The site is provided free of charge but depends on the support of its readers to be viable. If you’d like to help it keep revealing the news as it is and not what the Establishment wants you to hear – and can afford to without hardship – please click here to arrange a one-off or modest monthly donation via PayPal or here to set up a monthly donation via GoCardless (SKWAWKBOX will contact you to confirm the GoCardless amount). Thanks for your solidarity so SKWAWKBOX can keep doing its job.

If you wish to republish this post for non-commercial use, you are welcome to do so – see here for more.

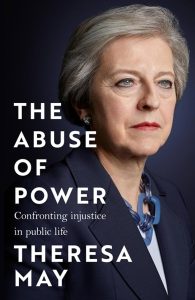

The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life – review

In The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life, Theresa May examines several “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, and advocates for a shift from careerism to public service is needed to achieve better governance. In Chris Featherstone‘s view, May’s selective case studies and weak defence of her role in controversial events like the Windrush scandal will do little either to forge a new model of British politics or rehabilitate her reputation.

The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life. Theresa May. Headline. 2023.

This is not your typical political memoir. The reader is assured of this by a glance at the dust jacket before even opening The Abuse of Power. In recent tradition, books by former Prime Ministers typically take the form of an attempt to correct the narrative of their time behind the famous black door (David Cameron’s For the Record), or to explain their route to the top job in UK politics (Tony Blair’s A Journey). Taking an alternative tack, Theresa May scrutinises a range of cases of what she calls “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, analysing the reasons behind them. Yet, despite this ostensibly different approach, The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

This is not your typical political memoir. The reader is assured of this by a glance at the dust jacket before even opening The Abuse of Power. In recent tradition, books by former Prime Ministers typically take the form of an attempt to correct the narrative of their time behind the famous black door (David Cameron’s For the Record), or to explain their route to the top job in UK politics (Tony Blair’s A Journey). Taking an alternative tack, Theresa May scrutinises a range of cases of what she calls “abuses of power” by politicians and civil servants involved in policy, analysing the reasons behind them. Yet, despite this ostensibly different approach, The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

The Abuse of Power reveals itself as an attempt to rehabilitate May’s reputation after her acrimonious exit from Downing Street in 2019.

The book examines examples of “injustice in public life”, highlighting the flaws in how government has approached and dealt with these issues. Examining cases ranging from the Salisbury Poisonings and the Hillsborough disaster to Brexit and the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, May highlights two factors. Firstly, she argues that it is the natural disposition of many in the public sector to place protecting the public sector ahead of the interests of those they serve. Secondly, she observes the growth of careerism and popularity-seeking amongst politicians, and the prioritisation of this over “the job they are there to do”.

May argues for the necessity of a deep attitudinal change in those in public life, especially from civil servants and politicians.

May’s proposed solution to these pervasive flaws in British public life is “service”, a theme that runs throughout her account of her own political career. As such, May argues for the necessity of a deep attitudinal change in those in public life, especially from civil servants and politicians. Her calls for greater diversity in those recruited to the civil service and a wider selection of candidates to stand in elections are well-intentioned, but unsupported with recommendations for how this can be achieved.

At first glance, her proposal that working for the broad public good could prevent many of the scandals she analyses appears somewhat convincing.

At first glance, her proposal that working for the broad public good could prevent many of the scandals she analyses appears somewhat convincing. The analysis used to form this argument is engaging, especially in those cases where May has personal knowledge, such as the Grenfell Tower tragedy (when external cladding on a tower-block caught fire, killing 72 people) or bullying and sexual harassment in Westminster. Yet, this reveals an underlying theme that accompanies the focus on “service”: May’s attention to governance rather than politics.

This partiality is reflected in May’s scepticism of politicians’ relationship with the media. In a chapter on social media, May characterises politicians’ use of social media as a superficial means of humanising them by showing the coffee cup they use or their typical breakfast. Despite raising important concerns on regulating the use of social media (whilst in Downing Street May initiated a government review of social media regulation, attacking the “vile” messages sent to female MPs), her simplistic and patronising framing of the use of social media in communication between politicians and the electorate is out of touch, and detracts from her argument.

May’s focus on effectively serving the public is coupled with a disregard for the politics of government, the importance of persuading people why policies are effective.

May’s media scepticism continues in her view of what characteristics are desirable in leaders. She condemns both short-term headline-seeking and the media focus that means if a leader does not speak to the media they are “written off.” These reactions against contemporary media and political communication methods are almost quaint, demonstrating wishful thinking for a bygone era of politics. May’s focus on effectively serving the public is coupled with a disregard for the politics of government, the importance of persuading people why policies are effective.

The Brexit chapter in particular highlights this inattention to the importance of persuading people – politicians and voters alike – of her approach. May accuses some MPs, including former Speaker John Bercow, of abusing their power by voting in their own, rather than the “national” interest when debating her Brexit deal. May’s compromise position – that the whole of the UK would remain in a de-facto customs union with the rest of the EU, and the UK and EU would have to agree to the UK’s withdrawal from this de-facto arrangement – received little support from either the remain or from the “hard Brexit” wings of her own party, or from opposition parties.

What stands out is May’s lack of engagement with the other views in the Brexit debates, giving insight into her difficulties building unity in the Conservative party during the Brexit process.

What stands out is May’s lack of engagement with the other views in the Brexit debates, giving insight into her difficulties building unity in the Conservative party during the Brexit process. Conspicuously absent is an explanation of how this judgement of “national interest” was made, other than this simply being May’s opinion. There is a ring of the internal-external attribution problem in her assessment, wherein she attributes her own actions to a personal conviction to pursue a “compromise” position in the national interest, and others’ actions to political machinations for personal gain. The chapter unintentionally highlights a root of the May government’s difficulties in persuading MPs and the public of the efficacy of their approach to Brexit.

The book’s highly selective approach to the cases analysed is epitomised in the chapter on the Hillsborough disaster, when 97 Liverpool football fans died in a crush, the UK’s worst sporting disaster. May confesses that when the tragedy occurred, she believed the “propaganda” put out by the police, politicians, and the media. May was by no means alone in this acceptance of the official line, yet, of the three groups she identifies in promulgating this lie, it is the police who come in for the major share of her analytical ire. As a former Conservative Home Secretary and Prime Minister, and current Conservative backbench MP, the inattention to the torrid relationship between Conservative politicians and Liverpool as a city as well as to the Hillsborough tragedy is a stark omission. Except for a couple of sentences on the role of politicians, the chapter largely diminishes their role in the framing of the tragedy in public discourse. Notably, almost all references are to “politicians”, intentionally skating over the (Conservative) party which they represented.

[May] fails to substantively support her claim and convince readers how Windrush is markedly different from the other abuses she examines.

Similarly, the explanation of the Windrush scandal, in which she was embroiled, is short and historically focused. May’s defence of the fiasco (which saw hundreds of Caribbean immigrants wrongfully issued with deportation notices) is that whilst other abuses of power she examines were to defend an institution, the Windrush case was in defence of a policy. She fails to substantively support her claim and convince readers how Windrush is markedly different from the other abuses she examines. May accuses the US of an abuse of power in the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and yet this would surely be defended by the Biden administration as the enaction and defence of their policy of troop withdrawal. Similarly, May’s defence of the use of the term “hostile environment” in her controversial immigration policy lacks depth. She suggests that when the term was proposed, it clearly referred to people who were in the UK illegally, implying that the controversy stems from its misinterpretation. This assumes it was merely the name of the policy, rather than the contested and controversial views that it was built on, with which critics disagreed.

The underlying message – that greater devotion to public service will solve these disparate and varied problems – falls flat. Her analysis of the ‘abuses’ catalogued reads at best naïve and at worst wilfully ignorant of the pervasive and deeply entwined nature of many of the causes of their causes.

May’s non-traditional memoir is an interesting read, giving some insight into cases that continue to puzzle policymakers (Brexit), and memorably controversial cases. However, the underlying message – that greater devotion to public service will solve these disparate and varied problems – falls flat. Her analysis of the “abuses” catalogued reads at best naïve and at worst wilfully ignorant of the pervasive and deeply entwined nature of many of the causes of their causes. This shallow defence of her time in government will do little to help polish May’s image, relying on unsupported claims about the intention of policies, such as those that led to the Windrush scandal, and selective attempts to blame others, as in the case of Brexit.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: pcruciatti on Shutterstock.